11

Caen, 25th of July, 1346

Midday

Hard hands gripped their arms and pinned them behind their backs. ‘No,’ said the man with the rings, and he rose to his feet. ‘These men are protected.’

The bishop slammed his fist down on the table. ‘You fool! They are spies, I tell you! Hang them!’

Bertrand stood up too, cradling his wounded arm. ‘My brother is right, Constable. You heard the messenger yesterday. Maldon and Merrivale have been sent to spy and report back to King Edward.’

‘Then we shall prevent them from doing so,’ the man with the rings said calmly. ‘Brother Geoffrey, Master Merrivale, your lives will be spared, but I fear we must detain you. Once your army retreats from Caen, you will be released.’

‘This is monstrous,’ Merrivale said sharply. ‘We are ambassadors. You cannot interfere with us.’

‘Oh, don’t go quoting the laws of war at me, herald,’ the man with the rings said wearily. ‘Ambassadors are also spies; always have been and always will be. It is part of their job. I didn’t need the messenger to tell me that.’ He paused for a moment, stroking his chin.

‘I still say we should hang them,’ the bishop growled.

‘I agree,’ said Bertrand. ‘Make an example of them.’

‘Your bellicosity does you credit, gentlemen. But if we hang their ambassadors, then they will start hanging ours, and so it will go on… I’m afraid we do still need such men, sometimes. And perhaps we can turn this to our advantage.’

‘What do you mean?’ asked Bertrand.

‘First, let us separate them. Keep Brother Geoffrey here in the castle. I will take the herald to one of the towers on the bridge of Saint-Pierre. He will be secure there, with no chance of escape, and I shall question him at my leisure.’

‘Question him? About what?’

The man with the rings smiled. ‘A herald to the Prince of Wales must know a great deal about the enemy’s plans and intentions. By the time I am finished with him, he will have told me everything he knows.’

‘You said you would spare our lives,’ Merrivale said.

‘And I shall. But more than that, Sir Herald, I will not promise you.’ He waved his hand, purple and blue light flashing from his rings. Two men-at-arms took hold of Brother Geoffrey. ‘Good luck, old friend,’ Geoffrey murmured. ‘May God watch over you.’

‘And you also,’ Merrivale said quietly.

The men-at-arms marched the black-robed canon away. Merrivale wondered if he would ever see him again. Two more men took his own arms, and the man with the mastiff device tapped him on the shoulder. ‘Come with me,’ he said.

Caen, 25th of July, 1346

Late afternoon

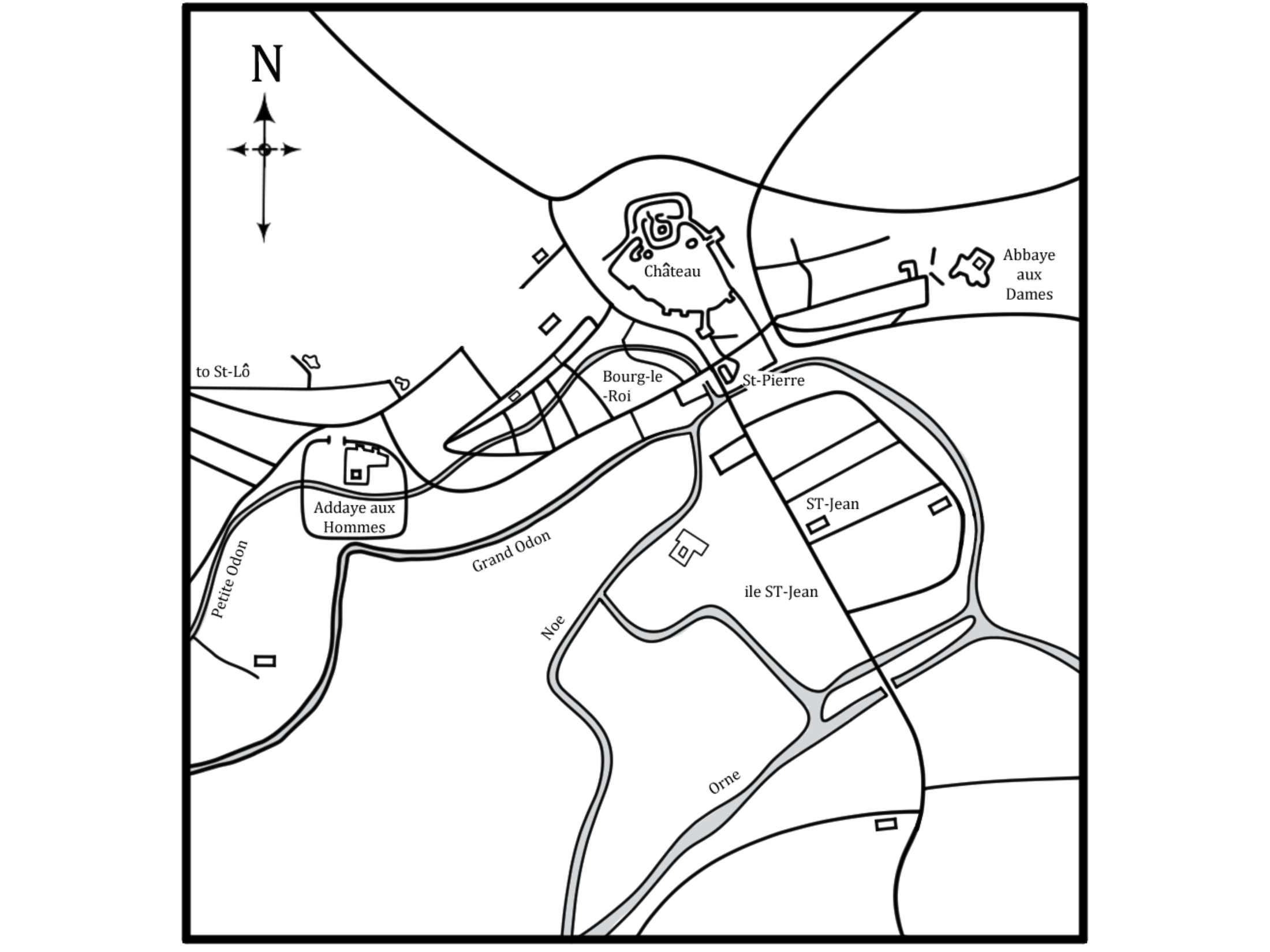

The guards took Merrivale to a room high up in one of the squat towers that guarded the southern end of the bridge of Saint-Pierre. Below he could see the bridge itself lined with half-timbered houses, some hanging out over the surging brown river. This was the Odon, which divided the two halves of the city. The river channel was broad; the tide, he guessed, was nearly full. The coast was only about ten miles away.

The single door into the chamber was locked from the outside. Even if he could get through it, the only way out was down the narrow spiral stair to another door at the foot of the tower. That door, as he had seen when they brought him in, was heavily guarded.

The windows were narrow, little more than arrow slits. Different angles showed him small parts of the city. Beyond the bridge to the north stood a big church, Saint-Pierre, its windows and buttresses rising above the riverbank; beyond it were the crowded buildings of Bourg-le-Roi. The towers of the abbey of Saint-Étienne could be seen in the distance. To the south was the district of Saint-Jean, streets lined with fine houses backing onto gardens. A pleasant, prosperous city, the herald thought, and big, too; not so big as London, but still powerful.

Everywhere he looked, he saw preparations for war. At the foot of the bridge a strong barricade had been thrown up, and he could see a host of defenders behind it, armour flashing and sparkling in the strong sunlight. Dozens of shallops and coracles were coming up the river on the incoming tide, all crowded with crossbowmen wearing white tunics.

White was the colour worn by Genoese mercenaries. Until now, apart from the detachment that had been overwhelmed at Pont-Hébert, they had seen nothing of these feared crossbowmen and their powerful weapons. Now, hundreds of them floated on the river, weapons at the ready. Merrivale wondered why they had been so late in arriving. Had Bertrand commanded this many crossbowmen earlier in the campaign, the outcome at Carentan and Saint-Lô might have been different; indeed, the English army might never have got ashore at Saint-Vaast.

Off to the west, smoke clouds billowed like the wall of a storm, lit from within by the red lightning of burning villages, coming steadily closer.

The room itself was not uncomfortable. There was a bed with a straw mattress and wool blankets, a painted wooden chest and a jeu de table, a small table inlaid with triangular patterns of dark wood and bone. Opening a drawer at one end, the herald found a stack of gaming pieces and a pair of dice. Thoughtfully he pulled up a wooden stool and arranged the pieces, then began rolling dice against himself, moving the pieces around the board.

He was halfway through a game when a key rattled in the lock and the door opened. The man with the rings walked into the room, closing the door behind him. He was about Merrivale’s own age, thin-faced and long-nosed, with an air of careless arrogance that came from generations of breeding and power. He wore an embroidered doublet and hose partly covered by a flowing silk surcoat bearing his arms: a gold lion on a blue field, quartered with an ornate gold cross on white. Of course, the herald thought with professional detachment; one of his ancestors had been King of Jerusalem.

‘I assume you know who I am,’ the man said.

Merrivale bowed. ‘Raoul de Brienne, Count of Eu and Guînes and Constable of France,’ he said. ‘I am at your service, my lord.’

‘A curious turn of phrase,’ Eu said. He surveyed his prisoner for a moment. Merrivale studied him in turn, waiting.

Eu pulled up another stool and sat down, studying the gaming table. ‘Are you fond of games of chance, herald?’

‘I dislike gambling, my lord. I prefer calculation.’

‘You dislike gambling? That must make you unique at King Edward’s court.’ The count gestured for Merrivale to sit. ‘Life itself is a gamble, herald. You wagered your life, when you came here to spy for your king.’

He rolled the dice and moved one of the white counters, and sat back looking at Merrivale again, his gaze steady.

‘Someone told you we were coming,’ Merrivale said. ‘Who was it?’

‘Do you really believe I will answer that question? Tell me instead why you came here.’

‘I have a message for you, my lord. And whoever told you we were spies was trying to stop that message from getting through. He hoped you would hang us out of hand, as the bishop and the Sire de Bertrand urged you to do.’

Eu stroked his chin, still watching him. ‘This message. What is it?’

‘Once I have told you, what then?’

‘That depends on the message,’ the count said, ‘and who it is from.’ He gestured towards the gaming table. ‘Your move.’

Merrivale rolled the dice, moved a black piece and pushed the dice back across the table. ‘My message is from the king,’ he said.

The count studied the game. ‘Ah,’ he said after a moment. ‘I see.’

‘But you had already guessed this,’ Merrivale said. ‘That is the real reason why you intervened to stop the bishop from killing us. You wanted to hear what I had to say.’

‘Let us just say your arrival was not unexpected.’ The count picked up the dice and rolled them. ‘And what does Edward Plantagenet want with me?’

Merrivale did not answer directly. ‘You will know by now, my lord, that Godefroi d’Harcourt’s revolt against King Philip has failed.’

‘Yes. It appears that Harcourt has fewer friends than he thought. Even his own brother has turned against him, and gone to join the royal army mustering at Rouen.’

‘As a loyal Frenchman, this must be pleasing to you,’ the herald said. ‘The threat of rebellion is averted and Normandy’s loyalty to the French crown has been secured.’ He paused. ‘Of course, my lord, it depends on who you really are. A Frenchman, or a Norman.’

Eu rolled the dice, studied the table for a long moment and finally moved a piece. ‘And what does your king want from me?’ he asked.

‘His Grace knows that you and the Queen of Navarre are planning a rebellion of your own. This revolt would be much more dangerous than Harcourt’s failed uprising. The queen is King Philip’s cousin. Your ancestors fought for the Holy Sepulchre, and the blood of kings and emperors runs in your veins. Where you lead, thousands will flock to follow you.’

The count said nothing. He picked up one of the gaming pieces, examined it for a moment, then put it back on the board.

‘If you rebel, His Grace will support you,’ Merrivale said. ‘He has fifteen thousand men, and more will come from England. You will need English support if you are to defeat King Philip and his royal army.’

‘What does Edward suggest I do?’

‘Join forces with him,’ Merrivale said. ‘When his army approaches Caen, open the gates of the city and bring your men over to join us.’

Eu made an impatient gesture. ‘If I do, King Philippe will declare me a rebel. All my lands and estates will be forfeit, and I will be no better off than Harcourt. What happens if I refuse Edward’s gentle offer?’

‘Then his Grace will storm the city,’ Merrivale said.

The count gestured towards the windows. ‘Look again, herald. Do you think that will be easy?’

‘The walls of Bourg-le-Roi are old and weak, and will be easy to undermine. Saint-Jean’s only protection, apart from these towers on the bridge, is the river and a wooden palisade. But the river can be swum or forded, and a child could climb over the palisade. Caen will fall, my lord, no matter how stoutly you defend it.’

‘Ah, but you have forgotten the castle. It is impregnable, and its storerooms are full. And I have four thousand men at my command, including a thousand crossbowmen. Even if the city falls, I can hold the castle for weeks.’

Merrivale nodded. ‘Ah, yes. You will hold out until the royal army arrives from Rouen to relieve you. King Edward will be forced to retreat, and the power and prestige of King Philip will grow stronger. The dream of rebellion and a free Normandy will recede into the distance. It would appear you have made your choice, my lord. You are French, after all.’

The count rose to his feet and stood looking down at him. ‘I told you earlier that you were gambling with your life,’ he said. ‘By speaking to me as you have done, you have forfeited your immunity as a herald. I could hang you right now.’

‘You could,’ Merrivale agreed. ‘But as I said, my lord, I prefer calculation to gambling.’

‘Well, let us see if you have calculated correctly. Is there anything you desire?’

‘Yes, my lord. You have in your service a man-at-arms named Macio Chauffin. I should like to speak with him.’

‘Chauffin? Why?’

‘An English knight was murdered shortly after we landed at Saint-Vaast, by one of our own men. I think Chauffin may have witnessed the murder. I would like to ask him what he knows.’

The count raised his eyebrows a little. ‘Why should I care if one of your men was killed? One less of the enemy to worry about.’

‘If indeed we are the enemy,’ said Merrivale. ‘But, my lord, this is a matter of murder, not warfare. And the principles of justice apply equally in France as they do in England, I think.’

Eu considered this. ‘You are bold with your demands,’ he said. ‘Perhaps I should take the bishop’s advice and hang you.’

A cold finger of doubt crept down Merrivale’s spine, and he wondered if he had overplayed his hand. ‘That is your lordship’s decision,’ he said.

‘It is,’ Eu agreed. ‘I wish you a good evening, Sir Herald.’

Caen, 25th of July, 1346

Evening

Time passed, and the wall of smoke grew closer. The sun, dipping into the west, was obscured by its clouds. Today, dusk fell early in Caen.

Macio Chauffin was the man who had arrested them outside the city walls. He had stripped off his surcoat and most of his armour, but still wore a mail tunic over a padded doublet. His balding head was fringed with dark hair like a monk’s tonsure. Merrivale guessed he was in his early forties.

‘Thank you for coming to see me,’ the herald said. ‘I am sorry I have no refreshment to offer you.’

‘I am here at my lord’s command,’ Chauffin replied. His face and voice were both wary, like a man expecting to be attacked.

‘If you will permit me, I have a few questions for you. I believe you met with Jean de Fierville on the road from Quettehou to Valognes the day we landed, the twelfth of July. During this meeting, did you see anyone else?’

Chauffin looked surprised, as if this was not the question he had been expecting. ‘Yes, I did. Just as we were finishing our… conversation, another English man-at-arms came riding up from Quettehou. I wasn’t expecting him, and I could see Fierville wasn’t either.’

‘What did you do?’

‘I thought it might be a trap, and I turned my horse and rode away. But I had only gone about a hundred yards when I heard Fierville calling me back. I turned again and saw the other man lying on the ground. He was dead by the time I rejoined Fierville.’

‘Did you see the men who killed him?’ Merrivale asked.

‘Yes,’ Chauffin said. ‘I did not see the actual shooting, but there were two archers standing only a few yards away, with strung bows and arrows at the nock. It was obvious that they were the killers.’

A gust of wind wafted through the windows, smelling of smoke. ‘Could you identify them?’ the herald asked.

Chauffin shook his head. ‘They wore no badges or blazons.’

‘Did either of them wear a red iron cap?’

‘No, they wore no headgear. I am positive of it.’

The caps could have been removed, of course. ‘Was one of them bald? With a scar across his scalp?’

Chauffin shook his head again.

‘What happened next?’ Merrivale asked.

‘Nothing. Fierville told the two archers to go, and they ran off. We debated about what to do with the body; he wanted to hide it, but there wasn’t time. Bertrand’s men were already coming down the road and hell was about to break loose. So we rode away and left him. Poor fellow,’ Chauffin said. ‘So young, too. His family will miss him.’

Merrivale looked at him sharply. ‘Did you recognise him?’

‘No.’ It was said so quickly and abruptly that the herald was quite certain he was lying.

‘You met Fierville by arrangement, I assume. Who told you where and when to meet him?’

Chauffin scratched his ear. ‘Does this have anything to do with the murder?’

‘It might.’

‘The letter arrived a week earlier,’ Chauffin said. ‘It came from someone in your camp, but I don’t know who.’

‘Might it have been Sir Thomas Holland?’ the herald asked.

Chauffin’s head jerked back in shock. ‘I don’t know who you are talking about.’

‘You and Sir Thomas and the Count of Eu served together in Prussia,’ Merrivale said. ‘You were together for about a year, first in Königsberg and then out on the frontier. At Allenstein and Rössel, I believe.’

Chauffin stared at him, lips clamped tightly together.

‘I am a herald,’ Merrivale said. ‘I know Fierville gave you information, and I know Sir Thomas Holland is betraying his country, but these matters do not fall within my jurisdiction. All I want to know is who killed that young knight.’

‘Holland is not a traitor.’

‘Fierville and yourself were go-betweens,’ the herald said, continuing as if Chauffin had not spoken. ‘Fierville carried messages from Holland to you, and you passed them on to the count; who, let us not forget, is also Constable of France. If this correspondence had come to light, Holland would have been attainted and executed. He would do anything to stop that from happening. His archers were keeping watch when you met Fierville that day, and when Sir Edmund Bray discovered the two of you together, they killed him.’

Chauffin’s eyelids flickered.

‘Yes, that was his name,’ Merrivale said. ‘You recognise it, don’t you?’

‘Yes,’ Chauffin said quietly.

‘How? Where had you heard it before?’

‘Fierville told me. When I rode back to join him.’

Another lie, Merrivale thought. ‘You are quite positive that you did not recognise these archers? They were not from Holland’s retinue?’

Chauffin stood up and walked to the door. ‘I know most of Holland’s trusted men,’ he said. ‘They were with us in Prussia too. The men I saw that day I had never seen before in my life. And you are wrong, Sir Herald. What Sir Thomas did was not treason.’

Merrivale raised his eyebrows. ‘No? But then treason is so often a matter of perspective, don’t you think? Did you know that, as well as delivering messages to you, Fierville was also reporting directly to Robert Bertrand?’

The look of astonishment on Chauffin’s face gave him the answer. ‘Fierville betrayed Godefroi d’Harcourt’s plans to the enemy,’ Merrivale said. ‘You must pray, messire, that he did not also know about the plot your master is hatching with the Queen of Navarre. Because if he did, that plan is also known to Bertrand, and probably by now to King Philip in Rouen. Tell your master this, and ask him where he wishes to place his bet.’

Caen, 26th of July, 1346

Morning

Now the smoke was very close, hanging over the faubourgs of the city and drifting in clouds above the castle and the Bourg-le-Roi. Looking through the narrow windows, Merrivale could see the sharp glitter of flames on the high ground west of the city. The storm was about to break.

Down on the bridge, the men around the barricade were alert, swords drawn, spears braced, crossbows ready. He could hear more men moving around on the roof of the tower overhead. Another column of men-at-arms and crossbowmen came down past the church of Saint-Pierre to the far end of the bridge and took up position in the half-timbered houses that lined the span, crouching in doorways or climbing up to lean out of windows The tide was nearly out, the river crowded with boats shrunk to a narrow channel with gleaming expanses of mud on either side.

Once again a key rasped in the lock and the door swung open. The Count of Eu walked into the room, clad in brilliantly polished metal armour with his bascinet tucked under one arm. The lion and cross on his surcoat were stitched with gold thread. Other men-at-arms followed him. One of them was Chauffin. Unlike the others, his face was pale and sweating and he looked sick with fear.

‘My apologies for disturbing you,’ the count said. ‘This room gives an excellent vantage point from which to survey the defences. My men and I will take post here.’

Merrivale bowed. ‘Do you wish me to withdraw, my lord?’

‘Stay. I may have need of your services before this is over.’

And what did that mean? the herald wondered. Eu had apparently made his choice; he seemed determined to fight.

‘I am at your service, my lord,’ he said. ‘If I may be so bold as to ask, is there any news of my friend Brother Geoffrey?’

‘He is in the dungeon at the castle. The Sire de Bertrand and the bishop have decided to remain there with their men. They will not join the defence of the city.’

‘We should all be in the castle,’ one of the other men-at-arms said. ‘We could hold it for weeks, long enough for King Philippe to arrive.’

‘And hand over the city and all its people to the enemy? We must make some attempt to defend them, Tancarville.’

‘But then why have you abandoned Bourg-le-Roi? At least it has walls.’

‘The walls are old and weak and easily undermined,’ Eu said, without looking at the herald. ‘Saint-Jean is an island, and easy to defend. Most of the population of Bourg-le-Roi have already fled here. We shall protect them.’

‘An island?’ Tancarville persisted. ‘See how low the water is! The enemy can cross the Odon with ease.’

Eu pointed to the boats full of crossbowmen drifting on the tide. ‘The river and the bridge are both strongly defended. Be at ease, Tancarville. The enemy shall not pass. We can hold Saint-Jean, and we will.’

Outside, the hot sun glared off the rooftops and the brown waters of the Odon. Up in the tower, the French men-at-arms waited, sweating in their armour as they watched the far end of the bridge and the lanes around the church of Saint-Pierre. Merrivale glanced again at Chauffin and saw terror plain in the other man’s face. He knows Eu is wrong, the herald thought. He knows the city will fall.

What has made the count change his mind? Why has he chosen to make his stand here, in practically defenceless Saint-Jean? Does he not know what will happen?

‘Here they come,’ someone murmured.

Three, four, five the archers came, distant figures in russet and green slipping around the apse of Saint-Pierre and staring out towards the river. In the tower they heard the distant clack of crossbows as the men in the boats began to shoot. One of the archers fell, rolling down the riverbank onto the gleaming foreshore. He tried to get up, but two more crossbow bolts slammed him back into the mud. The others vanished.

Voices murmured in the tower, almost whispering. ‘Have we seen them off?’

‘No. That was just a reconnaissance party. Those were only archers. The men-at-arms will come next.’

‘Our crossbowmen will see them off.’

‘No. Wait.’

More movement at the far end of the bridge, archers running out of cover and shooting at the men posted in the houses, dodging back again as the crossbow bolts lashed at them. Two fell kicking and twitching in the street, but suddenly there were more archers, and more, and the shower of arrows became a steady hail, thumping into the wooden walls and sticking out like porcupine quills. Beyond the bridge the watchers in the tower could see gleaming armour and bright shields, the English men-at-arms running forward to reinforce the archers, and Merrivale saw a flash of red and gold. Warwick the marshal was there, leading his troops from the front.

Streaks of flame arched through the air, fire arrows falling in swarms, plunging into walls and roofs tinder dry in the summer heat. Smoke rose almost at once, spreading across the bridge. Half a dozen French men-at-arms bolted from one burning house, running towards the shelter of the barricade at the southern end. The archers rose from cover and shot them as they ran, and their bodies tumbled down with arrows protruding from the joints of their armour. None reached safety.

Out on the river, the crossbowmen shot steadily, black bolts streaking through the air. Archers fell, their bodies littering the foreshore, but more and more were piling into the fight, shooting fast and accurately, and hundreds of grey-feathered arrows hissed like dragon’s teeth, shredding the air above the waters of the Odon and thudding into wood and flesh and bone. The showers of arrows scythed the Genoese down, some collapsing back into their boats and lying still, others falling overboard and drifting slowly downstream on the receding tide.

Some of these arrows were fire-tipped too. Already several boats were burning, and crossbowmen dived into the river to escape the flames; the archers shot them as they struggled in the water. The survivors crouched behind the gunwales of their boats and shot back desperately. Some archers were running out into the mud now, seeking to close the range, and now they were so close the crossbowmen could not miss. More archers fell and died, but the deadly rain of arrows continued.

In the tower room the voices whispered again. ‘No matter how many of them we kill, they keep coming. They do not stop.’

Welsh spearmen, men from Merioneth and Caernarvon, ran down the bank and plunged into the river, half wading and half swimming towards the boats. The fire arrows streaked out again and another boat began to burn; its crew dived into the stream, and then the Welsh were on them, spears rising and falling until the brown waters of the Odon were streaked with blood. In the boat nearest the bridge a handful of crossbowmen were still shooting steadily, and a Welshman reared back clutching at a bolt protruding from his chest, and slid under the water. His comrades reached the boat, stabbing wildly inside with their spears, the Genoese clubbing at them with the butts of their crossbows; the boat capsized and pitched them all into the water, men stabbing and grappling with each other in a shouting, screaming frenzy until the bodies of friend and foe alike went still and began floating away towards the sea.

The houses on the bridge were burning fiercely now, flames roaring and sparks shooting into the air. One collapsed, spilling flaming timbers into the river. A few more French defenders broke cover and ran, preferring a quick death in the street to burning slowly in their houses, but most stood fast. The clatter of metal sounded through the smoke as the English worked their way from house to burning house, clearing the defenders, still covered by those deadly clouds of arrows. More English men-at-arms ran forward across the bridge.

‘I see Northampton’s colours,’ said one of the French knights, looking out of the lancet window. ‘The English constable is here. And Warwick, and Thomas Holland as well.’

‘Holland,’ said the Count of Eu. His lips twisted into a smile. ‘My old friend from Prussia. How ironic.’

Tancarville turned on him. ‘Your old friend who is going to kill us all! The defences are collapsing, Constable! They are eating us up! We might as well defend a sand dune against the tide!’

‘The barricade will hold firm,’ the Count of Eu said. Chauffin had closed his eyes, his lips moving in silent prayer.

An arrow rattled against the stone wall of the tower and bounced away. ‘I recommend you stand away from the windows,’ Merrivale said quietly.

‘Don’t be ridiculous,’ the man watching the bridge said. He wore an open-faced helmet rather than a visor. ‘The window is narrow and high. Their archers cannot possibly hit it.’

A rushing hiss and a noise like a storm of sleet, arrows hammering at the wall outside, and the man who had spoken fell back into the room with four arrows protruding from the bloody wreckage of his face, their points driven deep into his brain. More arrows flew through the window, streaks of death seeking their target, and another man gagged, clutching at his throat. He collapsed across the gaming table, which broke and smashed beneath his weight, and lay sprawled on the splintered wood with blood spurting around the feathered shaft. Everyone else ducked, while the storm went on and arrows continued to fly in showers into the room. Screams and shouts overhead told them the defenders on the tower roof were being picked off.

In the street below, all was chaos, men shouting and screaming, the hammer of weapons reverberating off the walls, smoke and flames blowing everywhere, and then the cry went up: ‘England! Saint George, Saint George!’, a shout of victory ripped from a thousand throats. ‘The barricade has fallen,’ Tancarville said, and he drew his sword. ‘We are next.’

He had barely finished speaking when something smashed hard against the door of the tower. Merrivale looked at the Count of Eu. ‘The city is lost, my lord,’ he said. ‘There is no point in further resistance. Let me parley on your behalf. I will speak to the earls of Warwick and Northampton and ask them to accept your surrender.’

Eu smiled wryly. ‘Find me Thomas Holland instead. I wish to surrender to him.’

The door reverberated like the stroke of doom. The English were using rams; it would not be long before they broke the door down and swarmed inside.

‘Why?’ the herald asked.

‘He saved my life once in Prussia,’ the count said. ‘This is the least I can do for him.’

Chauffin leaned against the wall, eyes closed. Spent arrows crunched under Merrivale’s feet like kindling as he walked across the room. Descending the spiral stair, he heard the ram smashing into the lower door again and again; by the time he reached the bottom of the tower, the wood was already splintering around the hinges. He raised his voice.

‘I am Merrivale, herald to his Highness the Prince of Wales! I am sent by the Count of Eu to parley!’

The hammering on the door ceased, and he heard a confused muttering outside. Drawing a deep breath, he lifted the bar of the door, swung it open and stepped outside. Swords and spear points raised to confront him lowered slowly – and, he thought, not without a little disappointment – when the men saw his herald’s tabard. The bridge around the barricade and the street behind it were covered with bodies, some still, some moving feebly. A wounded Frenchman waved a hand, struggling to sit up, and one of the English archers ran over to him, pulled his head back to expose his throat and plunged a knife into his neck. The air stank of smoke and fresh blood. Gurney and young Mortimer were there, breathing hard, their armour dented, bright surcoats splattered with blood. ‘Where is Sir Thomas Holland?’ Merrivale asked.

‘Here.’ Holland pushed through the crowd of men around the door. ‘What do you want with me?’

‘The Count of Eu is within,’ Merrivale said. ‘He asks that you receive his surrender. Will you accept it?’

Holland pushed his visor up. ‘Eu wishes to surrender? To me?’

‘Yes,’ Merrivale said.

Holland closed his eye, and for a moment Merrivale wondered if he intended to refuse. Then he opened his eye and smiled broadly. ‘Of course,’ he said, and he turned to his esquire. ‘Go and find my lord of Warwick. Tell him the battle is over. The city is ours.’

One by one the defeated men came down the stairs, handing over their swords. Eu was the last but one, and when he saw Holland, he unbuckled his sword belt and knelt and laid it at the English knight’s feet. With surprising kindness, Holland took the other man’s hand and raised him up, handing back his sword. ‘Fortune did not smile on you today, Raoul,’ he said.

‘Whereas it glows on you like the sun, my friend. I think you will achieve all that you desire now. I give you my parole that I will not attempt to escape.’

‘Of course. Is there anyone else inside?’

‘There is still one,’ the herald said.

Slowly, dragging his feet as if he was suddenly very weary, Macio Chauffin stepped out of the tower into the light, holding his sword belt in one hand. He had closed his visor to hide his face, but the mastiff on his surcoat was plain for everyone to see. Holland drew his breath with a sudden sharp hiss. But before he could move, Matthew Gurney stepped forward and took Chauffin’s sword.

‘Well met, Macio,’ he said softly. ‘Welcome home.’