21

Poissy, 14th of August, 1346

Morning

‘Well, that wasn’t supposed to happen,’ said the man from the West Country.

‘No,’ agreed the man from the north. ‘The French were damnably careless. They should have made certain that the bridge was completely destroyed, and ensured there was a decent guard on the north bank.’

‘That force from Amiens sent to protect it. Why were they so late?’

‘Their orders were delayed in arriving. That is all I have been told.’

They stood on the riverbank downstream from the bridge, watching the carpenters at work. ‘However, it hardly matters now,’ the man from the north said. ‘What’s done is done.’

‘I wish I had your philosophy.’

The man from the north smiled. ‘These things are sent to try us, my friend. Tribulations purify the soul, as Abelard said. Now we must decide what to do next.’

‘If all of Edward’s army escapes across the river, our entire plan is in ruins,’ said the man from the West Country. ‘They will march north to Flanders and safety, and Alençon and Hainault cannot attack Philip until Edward has been disposed of.’

The man from the north frowned. ‘As always, you exaggerate the danger. First, Edward is not marching anywhere, not yet. It will be some time before that bridge is fully repaired. Second, Philip’s army is still at Saint-Denis, north of the river. If Edward does cross, the French can easily cut him off.’

‘Will Philip remain at Saint-Denis?’

‘No, and there I concede you have a point. There is some risk.’ The man from the north pointed towards the columns of smoke rising in the east and spreading out on the soft wind. ‘Warwick and Harcourt are burning the suburbs of Paris now, trying to tempt Philip to cross the river and fight. This time, I think they will succeed; Philip has to protect Paris.’

‘The Parisians won’t forgive him if he doesn’t.’

‘Indeed. They are already accusing him and his councillors of betrayal. They have managed to get hold of a letter with the king’s seal insisting that the army does not have enough men to defend Paris and that the city should be abandoned. They are threatening revolt, and Philip will have to placate them.’

‘Where did this letter come from?’

‘I wrote it, of course. I have a copy of the seal, remember? The point is that once Philip is over the river, he can move west and trap the English here. We can trust Alençon and Hainault to remind him of this, even if he does not think of it for himself.’

‘But this is exactly what I mean. Once Philip is south of the river, that leaves the way open for Edward. All he needs to do is repair the bridge and he can cross and march away.’

The man from the north shook his head. ‘By the time the bridge is repaired, it will be too late. All the French will need to do is mop up. We will have already administered the coup de grâce, remember? Time to put our plan into effect.’

‘Is everything ready?’

‘It will happen exactly as we planned it.’ The man from the north smiled. ‘Just remember not to touch the eggs.’

Poissy, 14th of August, 1346

Late afternoon

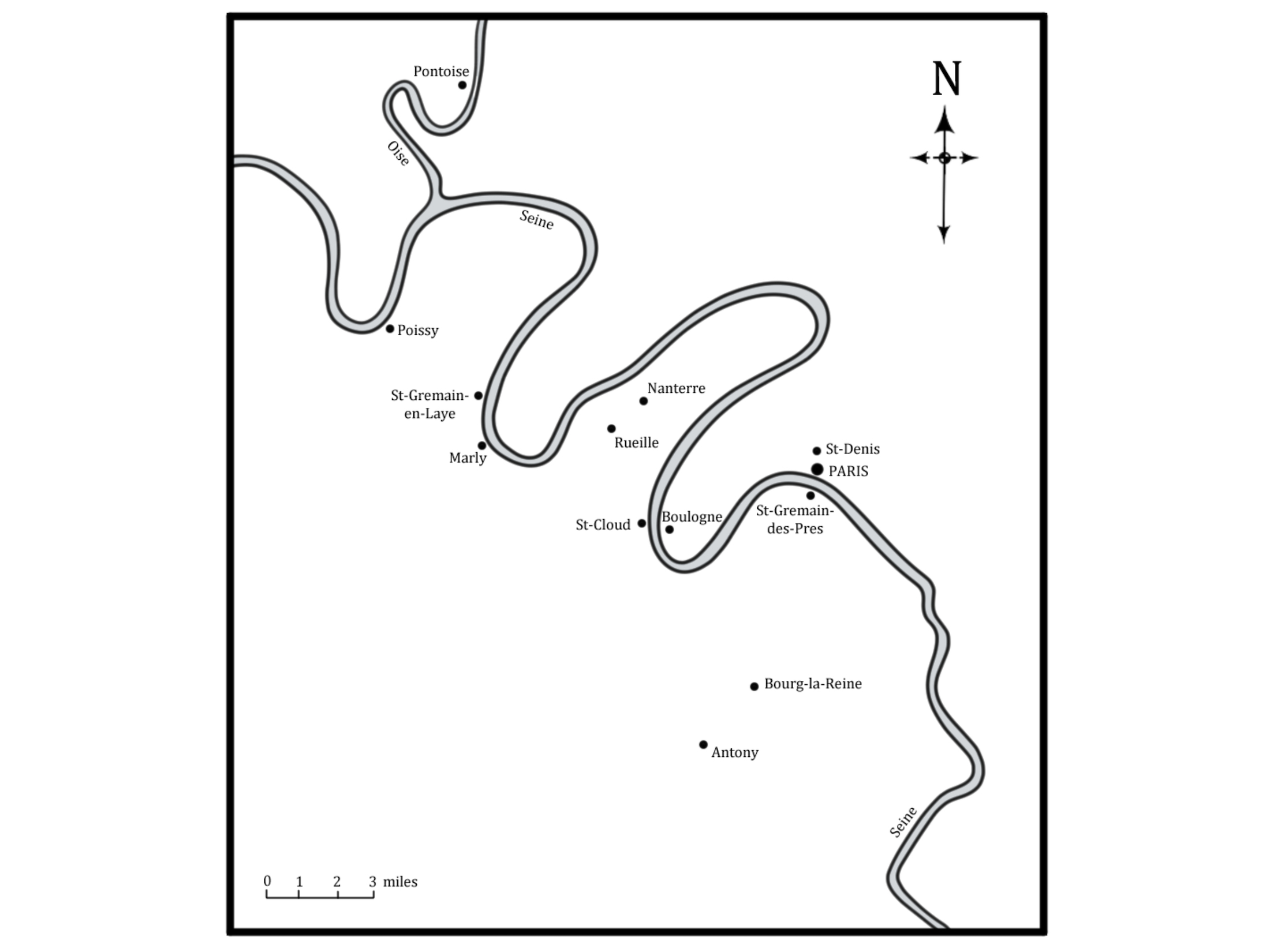

‘We’ve done everything we could,’ Warwick said. ‘We burned every village and manor house and monastery to the ground, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Montjoie, Nanterre, Saint-Cloud, the lot. Some of our hobelars were within shouting distance of the southern gates.’

‘We destroyed three more of the adversary’s palaces,’ said the Prince of Wales. ‘If that doesn’t make him come out and fight, nothing will.’

‘We don’t want him to fight, your Highness,’ said Northampton. ‘We only want to draw him south of the river and leave us with a free run to the north.’

The prince looked disappointed. ‘When shall we fight?’

‘When we are strong enough, Highness,’ said Lord Rowton. He had come up from the king’s headquarters to view the work on the bridge, meeting Warwick and the prince just as they returned from their raid towards Paris. His broken arm was strapped into a sling, and he seemed still to be in considerable pain. ‘When we reach Flanders and join forces with the rebels, then we shall be strong enough. Not before then.’

‘I think you underestimate the fighting spirit of our army, Lord Rowton,’ the prince snapped. ‘You should have more faith in our men.’

Rowton turned to him. ‘I bow to your superior experience, Highness. But the troops are tired from marching, food is running low, the captains are bickering amongst themselves, and the enemy have four times our numbers. Given all of this, do you think the army is ready to fight a battle, here and now?’

The prince stared at him. ‘I would not presume to make such a decision,’ he said. ‘I would defer to my father, the king. You see, Lord Rowton, I know my place. I am not sure you do.’

Rowton’s face went red. Merrivale looked up to see Warwick raise a hand to his face, hiding a smile. Northampton turned to the master carpenter. ‘How much longer, Hurley? And tell me in real time, not rosaries or Aves or chanting psalms.’

‘The bridge won’t be ready today, my lord. I can tell you that much for a fact.’

‘Tomorrow?’

‘Tomorrow evening, perhaps. No sooner.’

‘For God’s sake, Hurley!’ Northampton said. ‘The king wants this bridge repaired now. Work through the night if you have to.’

‘Now see here, Lord Constable!’ The master carpenter glared at him. ‘We bloody well did work through last night, and we’ll be working through the night to come. But this isn’t the Carentan causeway or Pont-Hébert. That gap is sixty feet long, and we’ll need two more support beams at least. Which means we have to find an oak tree that’s tall enough, fell it, cut two beams and size them, drag them up here and fix them to the supports, and then we still have to cut and plane down the planks to build the roadway and fix them in place. We’ve run out of nails too, and the blacksmith is sweating his guts out to forge some more, but it all takes time. So you tell the king, if he wants the bridge repaired any faster, he can come down here and pick up a fucking hammer!’

Northampton held up a hand. ‘Just do your best.’

‘I am certain you are working as hard as you can, Master Hurley,’ the prince said. Northampton and Warwick looked at each other, eyebrows raised. ‘And we are all grateful for your efforts. I shall tell my father as much when I see him.’

He turned and walked away. Merrivale prepared to follow, but Northampton raised his hand again. ‘Stay a moment, herald. We need a word.’

Merrivale inclined his head. ‘I am at your service, my lord.’

‘I am pleased to see that you survived your escapade at La Roche-Guyon unharmed,’ the constable said. ‘I assume your purpose was to rescue the Demoiselle de Tesson. Was she spying for you?’

‘I did not request her to do so,’ said Merrivale. ‘But yes, in effect that is what she was doing. I should add that I take full responsibility for the raid. I hope you have not rebuked Sir John Grey and Sir Richard Percy.’

‘Do you think rebuking them would have made the slightest difference to their behaviour?’ asked Warwick. ‘The king has shown us your report from the following day.’

Merrivale raised his eyebrows. ‘I was not certain that he had read it.’

‘He has read it, and he takes it very seriously. Something will happen at Poissy, you said. What?’

‘I don’t know, my lord. The demoiselle overheard the Count of Alençon say this to one of his officers, the Seigneur de Brus. That is all she knows.’

Rowton looked at the bridge. ‘Surely it is obvious,’ he said. ‘The French knew that if they blocked or broke down each bridge in turn, we would eventually arrive at Poissy. Assuming we cannot cross the river, and with the king still unwilling to sanction a retreat to Caen, we would have no choice but to stand and fight. This is where they intend to give battle.’

He looked at Northampton and Warwick. ‘Was his Highness by any chance right? Could we offer battle with any real hope of success?’

Northampton shook his head. ‘Reluctantly, Eustace, I must agree with you. The men are tired, and apart from a few companies like Grey and Percy’s, they are in no condition to give battle. And the terrain is flat, with no defensive features. The enemy would roll over us.’

‘Which undoubtedly has been their plan all along,’ Rowton said. ‘I said as much to the king, but he wouldn’t listen. Now all we can do is pray that Master Hurley can finish the bridge before the French army arrives on our doorstep.’

‘Oh, we’re all doing that,’ Warwick said. ‘The Bishop of Durham and his priests are in the priory right now, rubbing their knees raw while they pray to the Virgin and every saint in the calendar. But even if we do finish the bridge on time, it is still a hell of a long way to Flanders and safety. And don’t forget, gentlemen, before we reach Flanders, there is still another great river to cross. The Somme.’

Poissy, 15th of August, 1346

Late morning

‘Is there any word on Nicodemus?’ the herald asked. ‘Has he been seen?’

Mauro and Warin both shook their heads. ‘We have spoken to men from nearly every retinue in the army, señor,’ Mauro said. ‘We did not speak to Sir Edward de Tracey’s men, for I do not think they would tell me the truth. But all the others, even some of Holland’s men.’

‘I also called at the royal kitchen this morning,’ Warin said. ‘I wasn’t very welcome, because they’re all running about like chickens without heads, preparing for the feast this afternoon. But I wanted to know if Nicodemus had approached Curry or Master Clerebaud.’

‘And had he?’

Warin shook his head again. ‘No one has seen Nicodemus, or is prepared to admit it. I did learn one thing, though, from one of the scullions. Master Clerebaud has recently lost a lot of money at dice. He is deeply in debt.’

The herald considered this, wondering what it meant, if anything. ‘With whom does he gamble?’

‘No one knows, sir. He slips out pretty much every night, once they’ve cleaned up the kitchen. Only he didn’t go last night because they were already hard at work preparing for the feast.’

‘The enemy is at hand, food is running out, and your king has ordered a feast?’ Tiphaine asked.

Today was the feast day of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin; along with Lammas, it was the most important celebration of the summer. ‘It is a symbol,’ Merrivale said. ‘To sit down and feast with the enemy gathering in Paris a few miles away shows the army that he is in control. Rather than rush to cross the river by any means possible, abandoning our baggage, we will wait until the bridge is repaired and then cross in an orderly fashion.’

‘And you agree with this?’

‘As it happens, I do. In times of crisis, the leader must present a calm face to his men. If he is frightened or worried, he must never show it.’

Tiphaine looked dubious. ‘I think I would prefer to rush, and get away. But then I am not a king. Or a herald.’

‘You may go if you wish,’ he said gently.

‘Are you going?’

‘My duty is here. I am bidden to attend the feast along with the prince.’

Her chin came up. ‘If you stay, then I stay.’

‘There is one other thing that may be of interest, señor,’ said Mauro. ‘Nicodemus has vanished, but some of Tracey’s men are continuing to buy plunder. There has been plenty of spoil in the rich towns and abbeys we have passed. They are still making a great deal of money.’

Silence fell. The herald stared out across the fields towards Paris, where the smoke of yesterday’s fires still drifted in the air. The other three glanced at each other. ‘What are you thinking?’ Tiphaine asked.

‘I was right. Nicodemus is here. Warin, find Sir John Grey and Sir Richard Percy. Give them my compliments and ask them to turn out their men. Describe Nicodemus to them and ask them to search the camp from top to bottom. Check the baggage train in particular, any place where he might hide. Demoiselle, will you please find Sir Nicholas Courcy and ask him to meet me at the palace? Are Matt and Pip here?’

Warin motioned towards the two archers leaning on their bows thirty yards away. Merrivale turned to them. ‘Come with me,’ he said. ‘You too, Mauro. I may have need of you.’

Poissy, 15th of August, 1346

Midday

Coloyne, the yeoman of the kitchen, met them looking worried. ‘What is this about, herald? The feast begins in an hour’s time and we have much work to do.’

The royal cooks had established themselves in the palace kitchen. Fires roared on the hearths and pots bubbled and boiled, while outside men in bloody aprons butchered beef and mutton carcasses and prepared them for cooking. From the chapel of the priory next door came the sound of chanting; the king and his court were attending mass.

‘I must speak to Master Clerebaud,’ the herald said.

‘Very well, but please do not detain him for long.’

Glancing around the crowded kitchen, Merrivale could see no sign of Curry. Clerebaud was at work at the sauce table, chopping herbs with manic energy and stirring them into a pot over a low fire. He wiped the sweat from his forehead and straightened as Merrivale approached. His eyes were guarded. ‘How may I help you, herald?’

‘How much do you owe them?’ Merrivale asked.

‘How much do I… what are you talking about?’

‘Nicodemus and his friends. You play dice with them almost every night.’

Clerebaud looked around for a moment, then back at the herald. ‘I gamble with a few friends. I don’t know what you mean about Nicodemus.’

‘How much do you owe?’ the herald repeated.

‘…Thirty marks, or thereabouts. A trifling sum. I can easily win it back.’

Thirty marks, or twenty pounds, was more than even a skilled professional cook like Clerebaud earned in a year. ‘What sauces are you making for the banquet?’

Clerebaud looked startled by the question. ‘Cameline for roasting the beef. Sorrel verjuice for the carp. Saffron sauce, ginger sauce, garlic sauce, and a honey mustard glaze for the swan.’

‘Show me what you are putting in them.’

The sauce-maker indicated the table where his ingredients were laid out. Merrivale sifted through them, picking up bunches of herbs and examining them, sniffing a bowl of chopped garlic, dipping his finger in a crock of honey. He could see or smell nothing out of the ordinary. ‘Mauro? What do you think?’

‘Everything seems in order, señor.’

The herald turned back to Clerebaud. ‘The scullion who watches the pots, Curry. Where is he?’

Sudden terror crept into Clerebaud’s eyes. ‘I don’t know. He was here last night, but I haven’t seen him this morning.’

The herald remembered what Nell had said. ‘Has Curry threatened you?’

The terror increased. After a moment, Clerebaud nodded. ‘He said if they don’t get their money, they’ll skin me alive.’

Merrivale watched the other man’s eyes. ‘Curry also made you an offer, didn’t he? He asked you to do something in order to pay off the debt. What was it?’

The air in the kitchen was hot and full of steam and smoke, and sweat streamed down Clerebaud’s face. ‘I don’t know what you’re talking about.’

‘Tell me where Nicodemus is.’

‘I don’t know. I swear by the blood of Jesus, I haven’t seen him.’

‘You remember what happened at Lammas,’ Merrivale said. ‘The poisoned juvert.’

‘That was nothing to do with me!’

‘No. But if something happens today, it won’t be Curry and his men coming to flay you. It will be the king’s executioners.’

Back in the courtyard, they could hear singing again, the words of the Gloria echoing off stone walls.

Domine Fili unigenite, Iesu Christe,

Domine Deus, Agnus Dei, Filius Patris,

qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis;

qui tollis peccata mundi, suscipe deprecationem nostram.

Qui sedes ad dexteram Patris, miserere nobis.

‘He is lying, señor,’ Mauro said.

‘Of course he is. Stay here, and do not let him out of your sight.’

‘Yes, señor.’

Courcy had arrived, Gráinne inevitably at his elbow. Tiphaine was with them, standing what she judged was a safe distance from Gráinne; Matt and Pip lingered silently a few yards away. ‘Sir Nicholas,’ the herald said, ‘I need your knowledge of alchemy. How many kinds of poison are there?’

‘Christ knows,’ said Courcy. ‘Wolf’s-bane, belladonna, arsenic, strychnine, hemlock, opium, to name just a few. Do you want me to recite the entire pharmacopoeia?’

‘At Lisieux, you said the poison might have been acquired from an apothecary’s shop. Is there such a shop in Poissy?’

‘Yes, in the square by the church of Notre-Dame.’

‘Take me there, if you please.’

The looters had been thorough; every door in the square had been forced open and every building plundered, including the church. The windows of the apothecary’s shop had been smashed, fragments of glass and lead crunching under their boots as they entered. Cabinets and chests stood open, but by and large their contents had been left untouched; the looters had been looking for gold and silver or goods they could sell, and powders and tinctures were not considered valuable enough to take away.

Leaving Matt and Pip on guard outside, they searched the shop. ‘What are we looking for?’ Tiphaine asked.

‘Every box or bottle will have a label,’ Courcy said. ‘That’s so the ’pothecary doesn’t get the ingredients mixed up and accidentally sell a love potion when he was meant to provide a hair restorer.’ He paused for a moment, looking at her. ‘Sorry, I should have asked. You do know how to read?’

‘I was educated at the finest convent school in Normandy,’ Tiphaine snapped. ‘I know how to read.’

‘Sweet Jesus, you’re an idiot,’ Gráinne told her husband, cuffing him with one gauntleted hand.

‘Not every country believes in educating women, mo grá. I wasn’t sure how they did things in Normandy.’

They searched the shop, looking into cabinets and lifting the tops of majolica jars to smell the contents, Courcy checking the labels and muttering under his breath in Latin. Finding nothing, they moved through to the storeroom at the rear of the building. Almost at once they discovered what they were looking for, a wooden cabinet full of jars of dark treacly syrup and cloth packets containing roots and seeds. ‘Lachryma papaveris,’ Courcy said, pointing to the syrup. ‘And here we have Aconitum napellus, Atropa belladonna, Nux vomica and Arsenicum trisulphide. These are the poisons.’

‘Is anything missing?’ asked Merrivale.

‘It is hard to tell without an inventory. But the cabinet is well stocked. If someone did steal anything, they can’t have taken much.’

‘Where else might someone find poisons?’

‘Well, we’ve looted half a dozen towns since Lisieux. Or the poisoner might still have the stock he picked up in Caen.’

Merrivale shook his head. ‘They wouldn’t carry the poison this far in their baggage. The risk of discovery is too great. They will look for stocks near to hand.’

‘Where else in Poissy could they find aconitum?’ asked Gráinne.

Tiphaine snapped her fingers. ‘The priory here is a rich house. King Philippe’s sister is the prioress there. They would have their own physician.’

‘And the physician will have stocks of drugs,’ said Courcy. ‘But the king and prince are hearing mass at the priory now. Can we get in?’

The herald touched his tabard. ‘This is our passport,’ he said.

The kitchen, Mauro reflected, looked a little like one of those scenes from hell’s inferno that he remembered seeing painted on church walls back in Spain. Flames crackled, smoke and steam billowed towards the high ceiling. Men crouched over the fires, turning haunches of meat on spits. Pans clattered and pots bubbled. He mopped his forehead, watching Clerebaud adding breadcrumbs to the ginger sauce and stirring to thicken it, his face full of concentration.

Suddenly the sauce-maker frowned, rubbing a hand over his stomach and wincing in pain. He lifted the sauce pot from the fire, and hurried towards the door. ‘Where are you going?’ Mauro asked.

‘Garderobe. Christ, my guts are on fire.’

Mauro grinned. ‘Have you been eating your own cooking, señor?’

‘Very funny. Where are you going?’

‘I’m coming with you. My orders are not to let you out of my sight.’

The garderobe was in the stair turret next to the stables, a narrow dog-leg passage leading off the stair. ‘For God’s sake give me some privacy,’ Clerebaud pleaded. ‘I feel like hell. The last thing I need is you standing there watching me.’

‘I’ve seen worse,’ Mauro said, but the garderobe was tiny, with room only for one. He was forced to stand in the passage, waiting and listening to the sounds of distress. His mind was still dwelling on the subject of poison. ‘Seriously, señor. Was it something you ate?’

‘We had tripe sausages for dinner last night. I thought they smelled off.’

‘Is anyone else feeling ill?’

‘I don’t know. Perhaps I just had a bad piece. Oh God, I could shit through the eye of a needle.’

More groans followed, and eventually Clerebaud re-emerged, wiping his hands and looking a little pale. ‘Are you all right, señor?’ Mauro asked.

‘I have to be,’ Clerebaud said, mopping the sweat from his face again. ‘I have work to do.’

Poissy, 15th of August, 1346

Early afternoon

At the priory, the communion rite had begun.

Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis.

Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, dona nobis pacem.

The royal serjeants guarding the priory gates looked dubious when Merrivale demanded entrance. ‘The king gave strict orders not to be disturbed during mass, sir.’

‘This is the king’s business,’ Merrivale said. ‘I take full responsibility.’

The gates swung open. The chapel lay directly ahead, the cloister to the right, the prioress’s lodging to the left. ‘The infirmary will be beyond the cloister,’ Tiphaine said, pointing. They ran through the colonnade, pushing open doors into chapter house and scriptorium, and found a corridor leading to the kitchen and domestic buildings. ‘Here!’ Tiphaine called, and they followed her into a whitewashed room with an arched stone ceiling and beds arranged at neat intervals. A wooden table stood at one end of the room, a heavy iron-bound chest and an ambry behind it. The door of the ambry was open.

Courcy rummaged through it quickly. ‘Poppy syrup, belladonna, arsenic, all here.’ He turned, his eyes narrowed a little. ‘No aconitum,’ he said. ‘No wolf’s-bane.’

‘Would they necessarily keep stocks of it?’

‘It is a common treatment for fever and rheum. No well-stocked pharmacy is without it.’

‘So Nicodemus has the wolf’s-bane,’ Merrivale said. ‘And the feast begins at nones, as soon as mass is over.’ He looked up at the sun. ‘We have very little time.’

‘That saffron sauce smells good,’ Mauro said. ‘Saffron always reminds me of home.’

‘Spanish saffron is the best,’ Clerebaud agreed. ‘Far better than what they grow in France. This is to go with the poached eggs. Saffron sauce with eggs is one of the king’s favourite dishes.’

Mauro smiled. ‘Better that than tripe sausages.’

‘Don’t remind me.’ As if on cue, Clerebaud gave a sudden moan, doubling up and clutching at his stomach. ‘Christ, here we go again,’ he said, and he lifted the pot from the fire once more and ran out of the kitchen, heading for the garderobe. Mauro followed him. By the time he reached the top of the stair, Clerebaud was already inside the little chamber, groaning with pain.

‘Señor,’ Mauro called. ‘Are you all right?’

There was no answer, but the groaning ceased. The silence lasted for half a minute, and Mauro began to grow uneasy. ‘Señor!’ he called.

Still no answer. With a shock, Mauro realised what had happened. ‘Bastardo,’ he said under his breath, and hurried into the garderobe. The wooden seat had been lifted, and the shaft leading down to the ditch below was empty. There was no sign of Clerebaud.

Merrivale hurried into the palace courtyard followed by Tiphaine, Courcy and Gráinne, just as Mauro came running downstairs. ‘He is gone. He climbed down the garderobe shaft just a few moments ago. Señor, I am sorry.’

‘Don’t be. Quickly, to the kitchens.’

John Sully was in the courtyard, dog trotting at his heels, and Merrivale stopped for a moment in surprise. ‘Sir John! I thought you would be at mass.’

‘At my age, mass is irrelevant,’ the older man said. ‘The fact that I am still alive is proof enough of God’s favour.’ He looked at Merrivale. ‘What is wrong?’

‘Someone is trying to poison the king,’ Merrivale said, and he ran into the kitchen. The others followed. The pots of sauce stood lined up on the table, ready to be decanted for service. Merrivale bent over them, inhaling their rich aromas. Above the saffron sauce he stopped abruptly and stepped back. ‘What do you think?’ he asked Courcy.

The Irish knight leaned over the pot, sniffed and nodded. ‘I think we’ve found the wolf’s-bane,’ he said.

Coloyne was beside them, his face sharp with anxiety. ‘What is it?’

‘This pot has been poisoned with aconitum,’ Merrivale said. ‘For whom was this intended? The king’s table?’

‘For everyone in the hall. We are feeding three hundred people, all the nobles and senior knights. A dish of poached eggs and saffron sauce was to be placed on every table.’

Courcy’s jaw dropped. ‘Jesus Christ. They intended to kill every single captain. They would decapitate the entire army, and leave it leaderless in the face of the enemy.’

‘Yes,’ said Merrivale, staring at the pot. ‘That was their intention.’

‘But what about the feast?’ asked Coloyne, his face white with shock. ‘The king is due to take his seat in the hall in a few minutes.’

‘The other sauces may not have been poisoned,’ Merrivale said. ‘But we need to find a volunteer to taste the food, and quickly.’

‘There is no need to risk a man’s life,’ said Sully. He turned to his dog, snapping his fingers. ‘Sit, boy. Sit.’

‘No, Sir John,’ Merrivale said quietly. ‘I know how much he means to you.’

‘Aye, he’s a good and loyal companion. But he is still a dog, and his life is not worth that of a man.’ Sully picked up pieces of bread from the table and dipped them one by one in the other sauces. The animal looked up at him, brown eyes trusting, and opened its mouth to receive the first piece of bread, swallowing it quickly. The rest followed. Silence fell in the kitchen, everyone turning to watch.

‘The poison acts quickly,’ Courcy said. ‘We will soon know.’

Time passed slowly, the curl of smoke from the fires the only movement in the kitchen around them. The dog looked up at Sully, gave the gentlest of belches and sat back. Raising one leg and lowering its head, it began to lick its own bollocks. Gráinne watched with disapproval. ‘I reckon you’d do that, if you could,’ she said to her husband.

Sully closed his eyes with relief. Merrivale gripped his shoulder tightly and nodded to the yeoman of the kitchen. ‘Master Coloyne, you may serve your feast. The rest of you, come with me. We must find Clerebaud.’

The ditch below the garderobe shaft was muddy where someone had landed, and footprints had flattened the grass. Beyond the palace enclosure was another courtyard, surrounded by stone barns, leading to open fields where a few cows grazed in the middle distance, tended by a girl with a stick. To the right lay the picketed horses and rows of parked wagons of the baggage train.

Master Clerebaud the sauce-maker stood in the courtyard, leaning against a wooden water butt. His arms dangled loosely at his sides and his head lolled forward on his chest. Two arrows pinned him to the butt, holding him upright. Blood had welled up around the shafts, staining the front of his smock and dripping bright ruby droplets from its hem onto the ground.

He had been dead for no more than a few minutes. Merrivale ran past the barns and looked out across the fields. A man was running towards the pasture where the cows grazed. He carried a longbow in one hand and had a quiver slung across his back. Beyond the pasture lay a dense belt of woodland, part of the royal hunting preserve at Saint-Germain-en-Laye. If the archer gained the shelter of those trees, it would be impossible to find him.

Movement caught his eye, and he turned to see spearmen from the Red Company emerging from among the parked wagons. He cupped his hands to his mouth and shouted at them. ‘Quickly! Stop that man!’

Nell Driver heard the herald’s shout, and looked up to see Riccon Curry rushing towards her. She had never much liked him, especially after he started to bully her friend Master Clerebaud, and when she heard the herald shout the order to stop him, she did not even think. She drew the knife she carried at her belt and ran towards him.

She was small, but the knife was long and sharp and she knew how to use it; back in Hampshire, she had once had to drive off a wolf that was trying to attack her cattle. Curry saw her coming and reached for an arrow, but before he could draw it from the quiver, Nell was at close quarters, slashing with the knife. Curry dodged the first two blows and then stepped forward and kicked her, knocking her onto her back. He swore at her and raised his heavy bow to club her over the head, but Nell rolled away and the bow thudded into the ground. Curry overbalanced, and Nell rolled over again and stabbed him in the thigh.

The archer shouted, dropping the bow and clutching at his leg. Nell raised the knife again. Curry turned to see the Red Company spearmen charging towards him and realised he was cut off; he could no longer reach the shelter of the forest. He turned and ran back towards the town, sprinting with desperate speed despite his damaged leg, pursued by the spearmen. Drawing breath, Nell hitched up her kirtle and raced after them.

Matt raised his bow to shoot, but the herald knocked it aside. ‘No!’ he commanded. ‘This time, I want him alive.’

‘Then we had better get after him,’ said Courcy.

They ran, but fast as they went, Curry was faster still. The scullion was wounded and leaking blood, but he was also running for his life. Passing the palace, they raced down the high street towards the bridge. Merrivale watched the fleeing man closely; if Curry dodged into one of the narrow lanes that ran off the street, he could hole up in an abandoned house and be hard to discover. But Curry did not turn. Injured, panicked and desperate, he ran without thought, hoping against hope for rescue.

By the time they reached the bridge, injury and loss of blood had begun to take their toll. Hobbling rather than running now, he struggled on towards the gap in the centre of the span. ‘Stop him!’ Merrivale shouted to the carpenters. ‘Do not let him cross!’ The carpenters looked startled, but they picked up their hammers and mallets and turned to face the running man, barring his way.

Curry halted. The herald and his companions halted too, facing him, and Nell came panting up and joined them, still holding her bloody knife. The spearmen fanned out, prowling forward, intent on their quarry.

‘Riccon Curry,’ Merrivale said. ‘By the powers invested in me by the king, I am placing you under arrest for the killing of John Clerebaud.’

‘Go to hell,’ said Curry. Dragging his wounded leg, he staggered towards the parapet of the bridge.

‘You can still save yourself,’ Merrivale said. ‘Tell us where to find Nicodemus. If you do, I give you my word you will live.’

‘I will tell you nothing,’ said Curry. He hauled himself up onto the wooden parapet and stood for a moment, swaying.

‘Christ!’ Merrivale said sharply, and ran towards him, but he was too late. Gathering his strength, Curry turned to face the river, and jumped.

The current was strong; by the time Merrivale reached the parapet, Curry was already thirty yards downstream, splashing and floundering in the water. Pulling off his tabard and boots, the herald dived after him. He hit the river with a hard shock, water filling his mouth and nostrils, and kicked out, driving himself back towards the surface. Dimly he could hear people shouting from the bank. He spotted the scullion kicking feebly some distance downstream, and struck out after him.

Merrivale was a strong swimmer, having learned to swim in the cold pools of Dartmoor as a boy, but even so the currents buffeted him and sometimes tried to pull him under. He gained only slowly on the drifting man, and by the time he reached him, Curry had stopped moving. Hauling the inert body after him, the herald edged towards the southern shore. With the last of his strength he pulled the scullion into the shallows, where strong arms reached out and dragged them both ashore.

Mauro bent over him, eyes wide with anxiety. Tiphaine, white-faced, stood behind the manservant. Others gathered around too, a small crowd attracted by the chase and the shouting; he saw Mortimer and Gurney among them. The big leader of the Red Company’s spearmen was there too. ‘Señor!’ said Mauro. ‘Are you all right?’

Merrivale sat up and spat out river water. ‘Where is Curry?’

The scullion lay on his belly, eyes closed. Courcy knelt over him, pressing hard on his back and pumping the water out of his lungs in thin streams, but Curry did not move. After a while, Courcy lifted one of his arms and let it fall back limp. ‘Gone to feed the fires of hell,’ he said, and he turned the dead man over and closed his eyes with gentle fingers. O God, Son of the Father, who taketh away the sins of the world, have mercy upon us, the herald thought tiredly.

‘Wait a moment,’ Gurney said sharply. ‘Why did you call him Curry?’

‘That’s his name, sir,’ said Nell, looking down at the dead man with wide curious eyes. ‘Riccon Curry. He’s a sailor, or so he said.’

‘He damned well is not. He’s an archer, and his name is Jack Slade. He’s the man who joined Tracey’s company instead of mine.’

‘And deserted at Pont-Hébert after killing his comrade Jake Madford,’ the herald said. ‘He was working with Nicodemus all along.’ He looked at the Red Company man. ‘Have you found Nicodemus?’

‘Not yet, sir. But we found a wagon in the baggage train where we reckon a man has been sleeping at night. There were clothes and a bedroll, and several pairs of dice. One of them was weighted,’ he added.

So that was how they had trapped Clerebaud. They had let him win money at first, and then used the weighted dice to clean him out. Trapped in debt, he’d had no choice but to do whatever Nicodemus and Slade demanded of him.

‘It was Slade who poisoned the sauce at Lammas,’ the herald said. ‘He added the wolf’s-bane when he brought the sauce to the prince’s kitchen; he must have slipped it into one of the pots after the head cook had tasted it. I reckon that was a test, to see if it could be done. But Slade was not in the kitchens this morning.’

‘No, señor,’ said Mauro. ‘I think the poison was hidden in the garderobe. Clerebaud collected it when he went there, and hid it in his clothes when I could not see him. I am sorry, señor. I should have made sure.’

Yes, you should, the herald thought, but there was no point in dwelling on it now. ‘So, having added the poison to the sauce, Clerebaud then tried to escape, and Nicodemus ordered Slade to silence him.’ He looked down at the dead man. ‘Was he still hoping to make his own escape when he dived into the river? Or did he prefer death to capture?’

No one answered. Still dripping, Merrivale rose to his feet. Someone else came pushing through the crowd; another of the royal pages, a boy glittering in red and gold livery. ‘Sir Herald? The Prince of Wales bids you attend on him. Come quickly, sir. You must make ready for the feast.’

‘I will come,’ the herald said heavily. ‘But I doubt if I will have much appetite.’