The Origin and History of the Ancient Star Groups

THE ORIGIN AND HISTORY OF THE ANCIENT STAR GROUPS

Some man of yore

A nomenclature thought of and devised,

And forms sufficient found.

So thought he good to make the stellar groups,

That each by other lying orderly,

They might display their forms. And thus the stars

At once took names and rise familiar now.

ARATOS.

THE origin of the constellations is still open to conjecture, for, though all nations since the dawn of history have recognised these ancient stellar configurations, and at one period or another employed them in some symbolic or representative capacity, the fact remains that the researches of archæologists have failed to yield definite proof as to who first designed them and where they were first known.

There is little doubt that the constellations were the result of a deliberate plan, as La Place affirms. Possibly they were an endeavour on the part of some patriarch of the ancient world to grave an imperishable record of a great event, or a series of noteworthy occurrences in the world’s history, for all posterity to read, and although no Rosetta stone has been found as yet to enable the present race of man to decipher their meaning, still the problem attacked by the ablest savants of all nations has yielded theories respecting the origin and purposes of the constellations that cannot be far from the truth.

In the very dawn of the world, when human instinct first inspired observation, primitive man began to look about him and take stock of his environment. The daily wants of nature supplied, the natural phenomena would claim man’s attention, and first he would take cognisance of the sun, moon, and stars that provided life’s chief essential, light.

For purposes of identification alone, there must have been at an early date certain designations for the individual stars that gave rise to all subsequent stellar nomenclature. The sun, moon, and planets, the brighter luminaries, would first excite man’s interest and attention, and then the brightest stars would attract and mystify him.

As time went on, observation would soon indicate to human intelligence the relationship of the sun and moon to the fixed stars, and the seasonable difference in the appearance of the nocturnal skies.

All this would be in strict accord with the natural laws of the observational faculties. Such elementary knowledge of the heavenly bodies would presently lead to the establishment of certain facts relative to the stars, features concerning their apparent change in position, that if marked would render a service to the race.

Very early in the history of the world the stars must have served to record the passage of time, a service they have faithfully and accurately rendered mankind through all the ages to the present day.

The first tillers of the soil must have marked well the stars, and certain of them doubtless proclaimed the time of sowing and reaping. The circumpolar stars guided the rude crafts of the early navigators, and unquestionably in the earliest times they singled out “the star that never moves,” Polaris, as an unfailing and reliable beacon to direct their course.

The rising and setting of the stars thus became matters of paramount importance, governing alike the actions of the husbandmen and those who sailed the seas. Certain stars were also indicative of impending meteorological changes, and their appearance at particular seasons was watched for with keenest interest.

The wonder and mystery the stars inspired, and their utility in daily life, soon led to their becoming objects of idolatry, and as their importance increased, astrology, that pseudo-science, Kepler’s “foolish daughter of a wise mother,” sprang into being, and for a time suppressed, discouraged, and hampered the legitimate and scientific study of the heavens.

Thus early in the history of man we find the stars all-important to his welfare. No course was pursued or plan adopted without first consulting the heavenly bodies. They governed alike the policies of nations and the actions of individuals. They ruled absolutely over the destinies of the high and lowly, the rich and poor, and horoscopes became a necessity of life, and divination the highest pursuit of man.

In Sabianism, or star worship, we have, therefore, the earliest form of religion, and in astrology and the adoration of the stars the progenitors of the modern science of astronomy.

From this universal attention to the stars, there sprang up the myriad fancies and peculiar notions, the products of imagination, that peopled the sky with animals and quaint figures, and gave rise to the constellated stellar groups that have come down to us, and figure on the modern charts of the heavens.

There are many traditions that have emerged from the mists that shroud the distant past respecting the origin of the constellations, and the science of astronomy, and as that origin is antediluvian, the knowledge that we have of the subject must perforce be largely traditional in its character.

An early tradition affirms that the immediate descendants of Adam cultivated a knowledge of the stars, and that Seth and Enoch inscribed upon two pillars, one of brick, the other of stone, the names, meanings, secret virtues, and science of the stars, with the divisions of the zodiac.

Josephus states that he saw in Syria the pillar of stone, which alone remained in his day. The history of two mysterious pillars entwined with a serpent, the symbol of revolution, can be traced through all the ages, from remote antiquity until it reaches our dollar sign

Then there is a tradition that has survived the ages, that Noah, who was also known as Oannes and Janus, was the inventor of astronomy. It is certain that Noah and his family were soon worshipped and inextricably mixed with stars and gods.

The Chaldeans attributed their knowledge of the stars to Noah, who became a two-faced deity, as he could look backwards and forwards. He was known as “the God of Gates,” as he opened the door which God shut, and Noah and the Ark became Janus and Jana, solar and lunar deities. Of all this tradition meets us everywhere.

It is a remarkable fact that, from the earliest times, as far as we can judge from the cuneiform inscriptions and hieroglyphics that have been deciphered, the sign for God was a star.

Astronomy unites with history and archæology in pointing to the Euphrates Valley, and, as we might expect, the region of Mt. Ararat, as the home of those who originated the ancient constellation figures.

Authorities agree, for the most part, that the originators of Sabianism and stellar lore in this region were not the Semitic Babylonians, but a people generally termed “Akkadians,” a word meaning highlanders, or mountaineers, the most ancient race known to us, who came down from the mountainous region of Elam or Susiana, to the east of Assyria, bringing with them the rudiments of writing and civilisation.

The Babylonians, previous to the invasion of the Akkadai, unquestionably had some knowledge of the stars. It was thought in those early times that the mountains on the east supported the firmament, and that the zenith was fixed over Elam. There were observatories established in all the large cities of Chaldea, many of the shrines on the topmost terraces being dedicated to this purpose, and at an early date the stars were named and numbered.

The Babylonian Tablets, the oldest records extant, reveal that the Akkadians introduced their sphere and zodiac into Babylonia before the year 3000 B.C., and the zodiac of the Akkadians corresponds almost exactly with the signs we know to-day.

It seems almost folly to endeavour to set the date of the invention of the constellations, for that period must approximate the age of the habitable world, and in all probability the stellar figures known to us were not designed at any one time, and lost their originality by the varying conditions that time has wrought in the past, for even in comparatively recent years there have been many attempts to alter them.

Bailly, a brilliant scholar and eminent astronomer, contends that the phenomena of astronomy had been closely observed before the great races of mankind separated from the parent stock. He claims, and few would dispute him, an antediluvian race as the originators of astronomical science. In proof of this he cites the fact that there are ancient Persian records which refer to the four famous “Royal Stars” as having marked the four colures (the meridian points of the solstices and equinoxes), a fact only possible in antediluvian times.

Maunder, who has made a very careful study of archæology in its relation to the constellational figures, has revealed many interesting features in connection with them. He writes:

“The first feature which the old constellation figures present to us is a very striking one. They cover only a portion of the heavens, and a large region roughly circular in the southern hemisphere is left entirely vacant. Swartz was the first to make the significant suggestion that this space was left vacant because the inventors of the constellations lived too far north to permit of their viewing this part of the heavens.”

Pursuing this line of thought, Maunder considers that the designers of the figures lived, in all probability, between 36° and 42° north latitude, so that the constellations did not originate in Egypt or Babylon. By computing where the centre of the vacant space coincided with the southern pole, we get the date 2800 B.C., which was probably the date when the ancient work of constellation making was completed.

It has been remarked that among the constellation figures conspicuous by their absence are the following animals: the elephant, the camel, the hippopotamus, the crocodile, and the tiger, so it is reasonably safe to assume that neither India, Arabia, nor Egypt was the birthplace of the sphere. Greece, Italy, and Spain may be excluded on the ground that the lion figures as one of the constellations. We have left Asia Minor and Armenia, a region bounded by the Black, Mediterranean, Caspian, and Ægean seas, as the logical birthplace of the stellar figures. The fact that we find a ship among the stars warrants us in believing that it is on the coast of this country, and not in its interior, that we should expect to find the land where the constellations were first known.

The division of the zodiac into twelve signs, the number of months in the year, is one of very great significance, for we infer from the fact that it was so arranged to assist in the observation of the position of the sun among the stars.

Many of the authorities hold that the zodiac was planned while the spring equinox fell in the constellation Taurus. In support of this claim it may be said that, if this is the case, the sun was ascending all through the signs that face the east, and was descending all through the signs that face the west, a significant and logical arrangement which could hardly be accidental.

The date of the zodiac is given as 3000 B.C., which agrees very well with the significant position of the four Royal Stars previously mentioned which marked the four cardinal points, and were thus especially prominent.

A close inspection of the stellar groups yields many points of interest, notably the fact that everywhere there is indication of design and not chance in the arrangement and configuration. There seems to have been a definite idea in some one’s mind respecting them, a desire to perpetuate a vitally important record. It may be of interest to mention a few of the facts that have inclined scholars to this belief:

To begin with, we find many figures duplicated, and in most cases the two figures are close together in the sky. Thus we see the figures of two Dogs, two Bears, two Giants subduing Serpents, each pair in close proximity. Then there are two Goats, two Crowns, two Streams, and two Fishes bound together.

The zodiacal constellations are often clearly connected with neighbouring figures. We observe the Bull attacked by the Giant Hunter Orion, Aquarius pouring a stream of water into the mouth of the Southern Fish, the Scorpion attempting to sting Ophiuchus, and the Ram pressing down the head of the Sea Monster.

Again, one portion of the sky was known to the ancients as “the Sea,” and here we find, as we might expect, many marine creatures,—the Dolphin, the Whale, the Fishes, the Sea Goat, and the Southern Fish.

Other features in support of the theory of design are found in the half-figures, Pegasus, Taurus, and Argo, and the so-called Deluge group, comprising the Ship stranded on a rock, the Bird, the Altar, the Centaur offering a sacrifice, and the Bow set in the Cloud.

It is supposed that, at a time far remote, the Akkadians were conquered by the Semitic race, and that the conquerors imposed only their language on the conquered, adopting, it is said, the Akkadian mythology, laws, literature, and system of astronomy.

At an early date in the world’s history we find astronomy and astrology flourishing in China, India, Arabia, and Egypt.

The early astronomical annals of the Chinese reveal the fact that, before the year 2357 B.C., the Emperor Yao had divided the twelve zodiacal signs by the twenty-eight mansions of the moon.1

The Arabians are said to have received their astronomical knowledge from India, and in China, Arabia, and India we find an almost identical system, i.e., that of the Lunar Stations, or Lunar Mansions, employed to indicate the daily progress of the moon amid the stars.

India has been claimed as the birthplace of the constellation figures, but modern research, says Allen, finds little in Sanscrit literature to confirm this belief.

There is a controversy as to whether Indian astronomy was derived from Greece or independent of it. In support of the latter theory, it is said that the Brahmins were too proud to borrow their science from the Greeks or Arabs, and also that it was improbable that two rival Hindu sects, the Brahmins and Buddhists, should have adopted the same innovations in their calendars and religious symbolism. Again, the Greeks held Indian astronomy in high esteem, while the Hindus only bestowed a moderate praise on the Grecian science.

The Egyptians, on whose early monuments the twelve zodiacal signs are found, acknowledged that they derived their knowledge of the stars from the Chaldeans, and they were in turn the teachers of the Greeks as early as the time of Thales and Pythagoras.

Herodotus states that the Egyptians were the first of all mankind who invented the year and divided it into twelve parts, a statement much at variance to the accepted testimony of the Babylonian Tablets.

Of the constellations outside the zodiac, we find a few groups and stars mentioned at an early date, notably in the Old Testament, where, in the Book of Job, there are references to the Bear, Orion, and the Pleiades, names that have come down to us. Homer and Hesiod both mentioned the same constellations, which is indicative of the importance of these star groups in the eyes of the ancients. Hesiod also refers to the stars Arcturus and Sirius, and these two stars may well be considered the most ancient of all the stars from the standpoint of stellar nomenclature.

Authorities differ as to the source from which the Greek knowledge of the stars was derived, but in all probability it did not come from any one source but was imported from Egypt, Chaldea, and Phœnicia.

The founder of the science of astronomy in Greece was Thales, the head of the Ionic School of Philosophy, a citizen of Miletus, who lived about 540 B.C. It is said that he first taught the Greek navigators to steer by the Little instead of the Great Bear.

Eudoxus, a native of Cnidus, who lived about the fourth century B.C., a contemporary of Plato, was the first Greek who described the constellations with approximate completeness. He is reported to have visited Egypt and to have there received astronomical instruction. He wrote The Enoption, or The Mirror, and The Phenomena or Appearances, both prose works and unfortunately not extant, but Aratos, the Alexandrine poet, versified the latter work about 270 B.C., and it has descended to our day.

Aratos was a native of Soli in Cilicia, and Court Physician to Antigonus Gonatas, King of Macedonia. He was a contemporary of Aristophanes, Aristarchus, and Theocritus, and he always mentions the constellations as of unknown antiquity. His sphere accurately represented the heavens of about 2000 B.C. His poem has been considered an authority on stellar nomenclature, and has been closely followed by all subsequent delineators of the constellation figures.

This sphere of Eudoxus, which has been transmitted to us through the verses of Aratos, contained forty-five constellations, twenty in the northern hemisphere, twelve in the southern, and thirteen in the zodiacal group, the Pleiades being considered as a separate constellation in addition to Taurus.

Allen makes the following interesting reference to this famous poem: “When the poem entitled The Phenomena of Aratos was introduced at Rome by Cicero and other leading characters, we read that it became the polite amusement of the Roman ladies to work the celestial forms in gold and silver on the most costly hangings, and this had previously been done at Athens, where concave ceilings were also emblazoned with the heavenly figures.”

The Phenomena is the most ancient description of the constellations extant, and has been translated into all languages. Cicero and Germanicus Cæsar both made translations of it, and no less than thirty-five Greek commentaries on the work are known to us.

Eudoxus considered the heavens as divided up into constellations with recognised names. “He did not deal with the stars singly, but gave a sort of geographic description of their territorial position and limits, according to groups, distinguished by a common name.” His work’s chief value consists in the comprehensive view of the heavens it affords, and in the description of the constellated heavens in their entirety.

Although the contributions of Eudoxus and Aratos to astronomical literature are highly regarded and authoritative, the acknowledged founder of our scientific astronomy is Hipparchus, who was the first to discover the perpetual and apparent shifting of the stars known as the Precession of the Equinoxes. Only two of his works have come down to us, his Commentary, and the reproduction of his Star Catalogue by Ptolemy, who was known as “the Prince of Astronomers.” This catalogue enumerated 1022 stars, of which 914 form constellations, and 108 are unformed. It is held in much respect even by modern astronomers, and agrees in the main with the enumeration of Aratos. Procyon, however, appears as a constellation, and the asterism Equuleus, the foremost Horse, is added, an asterism that figures on modern star maps. The observations of Hipparchus were made between 162 and 127 B.C., while those of Ptolemy embodied in the Syntaxis, as his work was entitled, were made from 127 to 151 A.D.

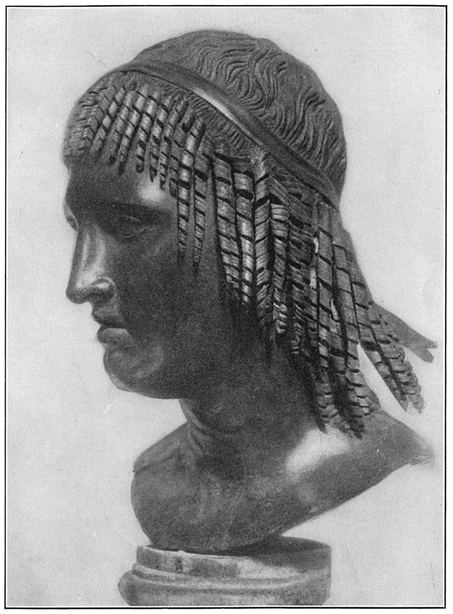

Ptolemy

National Museum, Naples

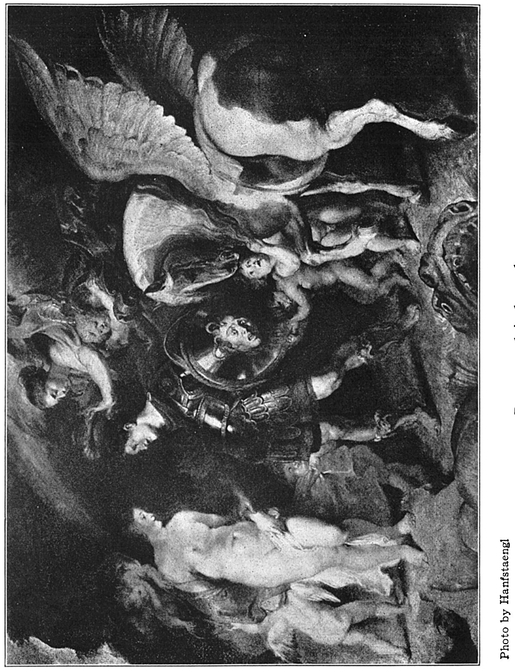

Perseus and Andromeda (Berlin)

The Syntaxis was practically an epitome of the results of the early star-gazers of Greece and Western Asia, and comprised a list of 1028 stars classified in forty-eight constellations. Each star is named by its position in the figure supposed to include the stars of the group. Thus the constellation Draco contains thirty-one stars, some of which received the following descriptive names: “the star upon the tongue,” “the star in the mouth,” “the star above the eye,” etc. This method of naming the stars continued in use until the eighteenth century, when a letter or a number with the Latin genitive of the constellation was used. In Ptolemy’s catalogue appears the first comparative list of stellar magnitudes.

The constellations of the Greeks were ultimately accepted and adopted by the Persians, Hindus, Arabs, the nations of Western Asia, and the Romans, from whom they have been borrowed by the modern world. To Greece, then, we are indebted for the figures now depicted on our celestial globes and the many interesting myths associated with them, notably the legend of Perseus and Andromeda, which is fully illustrated in the starry skies.

Although the savages of prehistoric times first bequeathed the stellar configurations to science, we listen to their harsh ideas, as Bacon puts it, “as they come to us blown softly through the flutes of the Grecians.”

From the time of Ptolemy till the year 1252, no advance of importance was made in the matter of cataloguing the stars, but in this latter year there appeared the celebrated Alphonsine Tables compiled by Arabian or Moorish astronomers at Toledo under the auspices of the subsequent King Alphonso X., known as “the Wise.”

A correction of Ptolemy’s sphere was published by the Arabian astronomer Ulugh Beg in 1420 A.D., in which there was a description of the constellations derived from A1-Sufi’s translation of five centuries previously.

The catalogues of Copernicus and Tycho Brahe followed, the former’s great work laying the foundations of modern astronomy. In 1603 the Uranometria of Johann Bayer appeared in Germany. This chart contained forty-eight constellations and a list of 709 stars. Bayer invented the system in vogue to-day of denoting each star by a letter of the Greek alphabet, the brightest star in each figure being designated Alpha with the Latin genitive of the constellation. It was soon found that the stars in many of the groups exceeded the number of letters in the alphabet, and such stars were denoted by the letters of the Roman alphabet.

Succeeding Bayer’s catalogue there appeared consecutively the charts of Bartsch, Schiller, Kepler, Royer, Halley, and in 1690 that of Hevelius, who added the asterisms of the Hunting Dogs, the Giraffe, the Lizard, the Unicorn, the Lynx, the Sextant, Fox and Goose, and Sobieski’s Shield, all recognised by modern astronomers.2

Flamsteed’s catalogue, published in 1719, comprised fifty-four constellation figures, and exhibited a new method of stellar designation, the stars being consecutively numbered in the order of their right ascension, a method employed in modern charts for the fainter stars.

La Caille, known as “the true Columbus of the southern sky,” in his publications of 1752 and 1763, invented fourteen new star groups which included the names of many instruments of the sciences and fine arts, the majority of which have been rejected by modern delineators of the constellations.

Subsequently Le Monnier, Bode, and Lalande published stellar catalogues, adding new asterisms, the latter’s chart containing a total of eighty-eight constellations.

In 1840 the famous German astronomer Argelander published his star catalogue, the most complete that had appeared up to that time. It contained 210,000 stars. Argelander brought order where there had been much confusion, by separating one constellation from another by irregular boundary lines, so that all the stars would be embraced within the borders of some stellar figure. His system is employed in many of the modern charts of the heavens.3

To-day there are over a hundred large catalogues of the stars, but there is a discrepancy in the number of constellations accepted by astronomers. Prof. Young recognised sixty-seven as in ordinary use, and in these northern latitudes about fifty-five are generally known.

Allen tells us that “eighty or ninety may be considered as now more or less acknowledged, while probably a million stars are laid down on the various modern maps, and this is soon to be increased perhaps to forty million on the completion of the present photographic work for this object by the international association of eighteen observatories engaged upon it in different parts of the world.”

In conclusion, it may be of interest to review briefly the conception of the firmament in vogue in ancient times among the different nations of the old world.

The Persians are said to have considered 3000 years ago that the whole heavens were divided up into four great districts, each watched over by one of the “Royal Stars,” Aldebaran, Antares, Regulus, and Fomalhaut.

The Assyrians looked upon the stars as divinities, endowed with beneficent or evil powers.

Among the Chaldeans the sky was regarded as a boat, shaped like a basket. The space below was the earth, which was flat and surrounded by water.

The Egyptians worshipped Osiris and Isis as ancestors, and showed Plutarch their graves, and the stars into which they had been metamorphosed.

The ancient Peruvians thought that there was not a beast or bird on earth whose shape or image did not shine in the sky. They considered the luminaries and stars guardian divinities and worshipped them. They also thought that the stars were the children of the sun and moon.

The Hebrews had a notion that the sun, moon, and stars danced before Adam in Paradise.

The Bushmen, or early inhabitants of Africa, regarded the more conspicuous stars as men, lions, tortoises, etc. They believed that the sun, moon, and stars were once mortals on earth, or even animals, or inorganic substances which happened to get translated to the skies.

In New Zealand heroes were thought to become stars of greater or less brightness according to the number of their victims slain in battle.

The North American Indians believed that many of the stars were living creatures, and knew Ursa Major as a Bear, the same figure known in the Far East.

The Tannese Islanders divided the heavens into constellations with definite traditions to account for the canoes, ducks, and children that they see in the skies.

In the South Pacific islands dying men will announce their intention of becoming a star, and even mention the particular part of the heavens where they are to be looked for.

The Eskimos thought that some of the stars had been men and others different sorts of animals and fishes, which was also the mythical belief of the Greeks and Romans.

According to Slavonic mythology the stars are regarded as living in habitual intercourse with men and their affairs.

An ancient legend was that there were no stars till the giants of old, throwing stones at the sun, pierced holes in the sky, and let the light of that orb shine through the holes which we call stars,—and Anaximenes thought that the stars were fixed in the dome of heaven like nails.

Thus we find, as some one has put it, that “astronomy like a golden thread runs through history and binds together all tribes and peoples of the earth,” and the girdle of stars we view nightly remains as the most ancient monument of the work of intelligent man, “the oldest picture book of all.”