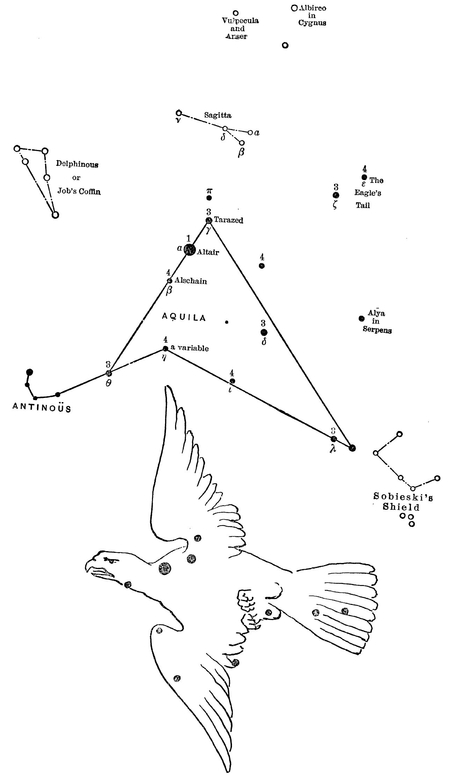

Aquila

The Eagle

AQUILA

AQUILA

THE EAGLE

Aquila the next

Divides the ether with her ardent wing

Beneath the Swan, not far from Pegasus,

Poetic Eagle.

THE history of the constellation Aquila, the Eagle, is especially interesting both because in this case we can trace it back very clearly to the earliest times, and the original Euphratean name has been preserved.

The Sumerian-Akkadian Eagle was “Alula” (the great spirit), the symbol of the noontide sun, and in all probability the origin of the present constellation. On a Euphratean uranographic stone of about 1200 B.C., there is a bird figured, known as the Eagle, which is supposed to represent the constellation of Aquila.

The Latins knew this constellation as Aquila, and their poets called it “Jovis Ales” and “Jovis Nutrix,” the “Bird” and the “Nurse of Jove.” Ovid called it “Merops,” King of the island of Cos, in the Archipelago, turned into the Eagle of the sky, and placed among the stars by Juno. Others thought it some Æthiopian king like Cepheus.

Aquila is generally joined with Antinoüs, an asterism invented by Tycho Brahe. Antinous was a youth of Bithynia in Asia Minor, who came to an untimely death by drowning in the river Nile. So greatly was his death lamented by the Emperor Adrian, that he erected a temple to his memory, and built in honour of him a splendid city on the banks of the Nile.

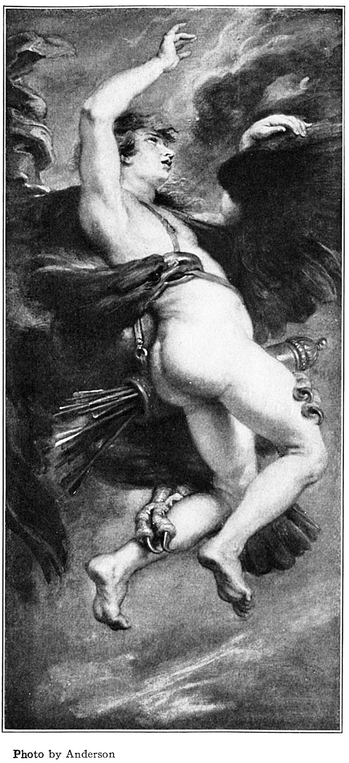

In Greece, the eagle was the bird of Zeus, and is represented as bearing aloft in his talons a beautiful boy. This youth is sometimes called Ganymede, whom Jupiter, as the story runs, desiring for his cup-bearer, sent the eagle to seize and carry up to heaven.

One of Ovid’s Metamorphoses treats of Ganymede, the youthful cup-bearer, and Elizabeth Barrett Browning thus translates it in part:

But sovran Jove’s rapacious bird, the regal

High percher on the lightning, the great eagle,

Drove down with rushing wings; and thinking how,

By Cupid’s help, he bore from Ida’s brow

A cup-boy for his master, he inclined

To yield, in just return, an influence kind;

The god being honoured in his lady’s woe.

Aquarius as we have seen was also supposed to represent Ganymede, and there seems to have been a connection between the constellations Aquarius and Aquila.

Another story claims that Jupiter himself assumed the form of an eagle and seized and carried off Ganymede, and Aquila was known as the bird of Jove and bearer of his thunder.

Horace thus alludes to this famous bird:

Jove for the prince of birds decreed,

And carrier of his thunder, too,

The bird whom golden Ganymede

Too well for trusty agent knew.

Gladstone’s translation.

Some have imagined that Aquila was the eagle which brought nectar to Jupiter, while he lay concealed in the cave at Crete to avoid the fury of his father Saturn, and this is in accordance with the legend of the Rig-Veda that Aquila bore the Soma (the invigorating juice) to India, “rushing impetuously to the vase or pitcher” (the constellation Aquarius). This legend serves to corroborate the view that the Water Bearer and the Eagle were closely associated.

Ganymede Seized by the Eagle

Painting by Rubens. Gallery of the Prado, Madrid

Ganymede

Painting by George Frederick Watts

Some of the ancient poets say that this is the eagle which furnished Jupiter with weapons in his war with the giants. In accordance with this version early representations added an arrow held in the Eagle’s talons. Manilius wrote:

The tow’ring Eagle next doth boldly soar,

As if the thunder in his claws he bore;

He ’s worthy Jove since he, a bird, supplies

The heaven with sacred bolts, and arms the skies.

On Burritt’s map, Antinoüs is represented as grasping a bow and arrows as he is borne aloft in the talons of the Eagle. In this connection there may be a significance in the position of the asterism Sagitta, the Arrow, just north of Aquila.

Among the Australians Aquila is called “Totyarguil,” and represents a man who, when bathing, was killed by a fabulous animal, a kind of kelpie, as in Greece Orion was killed by a scorpion and translated to the stars.

The Hebrews know this constellation as “Neshr,” an eagle, falcon, or vulture. The Arabians called it “Al- cOk b,” probably their black eagle. Grotius and Bayer both called the constellation “Altair,” the name now borne by its brightest star.

b,” probably their black eagle. Grotius and Bayer both called the constellation “Altair,” the name now borne by its brightest star.

The Turks called Aquila the “Hunting Eagle,” and through all the ages it has been known as a bird of prey, the “Eagle of the Winds,” the “Soaring Eagle,” as contrasted with Vega near by, the “Swooping or Falling Eagle.”

Here over the face of the waters as it were, just above the region of the sky known to the ancients as “the Sea,” we find three birds in flight, two eagles and a swan, our Lyra, being anciently known as “the Falling Eagle.” There is a significance in this arrangement that has never been satisfactorily explained. Dupuis advanced the idea that the famous three Stymphalian Birds of mythology were represented by the constellations Aquila, Cygnus, and Lyra, grouped near Hercules, whose fifth labour it was to slay them.

On the coins of many ancient countries the eagle appears. On the coinage of Sinope it is shown perched on the dolphin. In connection with the story of Ganymede, it appears on the coinage of Chalcis and Dardanos. One coin bearing the prominent stars, says Allen, was struck in Rome in 94 B.C., by Manius Nepos, and a coin of Agrigentum bears Aquila, with Cancer on the reverse,—the one setting as the other rises.

The Chinese have here the Draught Oxen mentioned in the book of Odes, compiled about 500 B.C., and strangely enough Alpha Aquilæ, or Altair, is known among the Japanese as the boy with the ox.12

This constellation and Lyra are associated with the curious Chinese legend of the Spinning Damsel and the Magpie Bridge, a legend current in Korea also. It is as follows: A cowherd fell in love with the spinning damsel. Her father in anger banished them both to the sky, where the cowherd became α, β, and ϒ Aquilæ, and the spinning damsel the constellation Lyra. The father decreed that they should meet once a year, if they could contrive to cross the river (the Milky Way). This they were enabled to do by their friends the magpies, who still once a year, the seventh night of the seventh moon, congregate at the crossing point, and form a bridge for them to pass over. In Korea if a magpie is seen about its usual haunts at this time the children stone it for shirking its duty. According to Lafcadio Hearn, this legend is the basis of the Japanese festival called “Tanabata.” The sky lovers here are known as “the Herdsman and the Weaver,” and when the meeting occurs it is said that the lover stars burn with five different colours. If rain falls at the time set for the crossing, the meeting fails to occur. For this reason rain on the Tanabata night is called the rain of tears.

Dr. Seiss regards Aquila as symbolical of the Wounded Prince or Christ suffering for mankind.

Aquila contains a star of the first magnitude called “Altair,” a Aquilæ, to which Mrs. Martin in her delightful book, The Friendly Stars, thus charmingly refers: “Then there comes a soft June evening with its lovely twilight that begins with the last song of the woodthrush and ends with the first strenuous admonitions of the whippoorwill, and almost as if it were an impulse of nature one walks to the eastern end of the porch and looks for Altair. It is sure to be there, smiling at one just over the tree-tops with a bright companion on either side, the three gently advancing in a straight line as if they were walking the Milky Way hand in hand and three abreast.”

Allen tells us that the name of this beautiful star is from a part of the Arabic name for the constellation, and means the flying vulture.

Ovid thus alludes to the rising of Altair:

Now view the skies

And you ’ll behold Jove’s hook’d-bill bird arise.

This star was ill omened in astrology, and supposed to portend danger from reptiles. It is an important star for the mariner, however, as the moon’s distance is taken from it for computing longitude at sea.

According to Dr. Elkin, Altair is fifteen light years distant from the earth. It is said to be approaching the earth at the rate of twenty-seven miles per second, and culminates at 9 P.M. on the 1st of September.

The radiant point of the meteors known as the Aquilids, visible from June 7th to August 12th, is located about five degrees east of Altair. Strangely enough in the year 389 A.D., a famous temporary star, or comet, appeared in this vicinity. Cuspinianus stated that it equalled Venus in brilliancy. It vanished after three weeks’ visibility.

Altair with its two companions Beta and Gamma Aquilæ constitute the so-called “Family of Aquila.” The line joining these stars is five degrees in length. In China these stars were known as “Ho Koo,” meaning “a river drum,” and the Persians-called them the “Star Striking Falcon.” They formed the 23d Hindu lunar station known as “the Ear.” The regent of the asterism is Vishnu, and these three stars represent the three steps with which Vishnu is said in the early Hindu mythology to have strode through heaven. A trident is often given as the figure of this group.

Eta Aquilæ is a remarkable variable star. Its greatest brightness continues but forty hours. It then gradually diminishes for sixty-six hours, when its lustre remains stationary for thirty hours. It then waxes brighter and brighter until it appears again as a star of the third magnitude. From these phenomena, says Burritt, it is inferred that it not only has spots on its surface like our sun, but that it also turns on its axis. The spectrum of this star is similar to that of our sun. Lockyer thinks it is a spectroscopic binary, that is a star with a companion too close to be revealed by the most powerful telescope.