Cepheus

The King

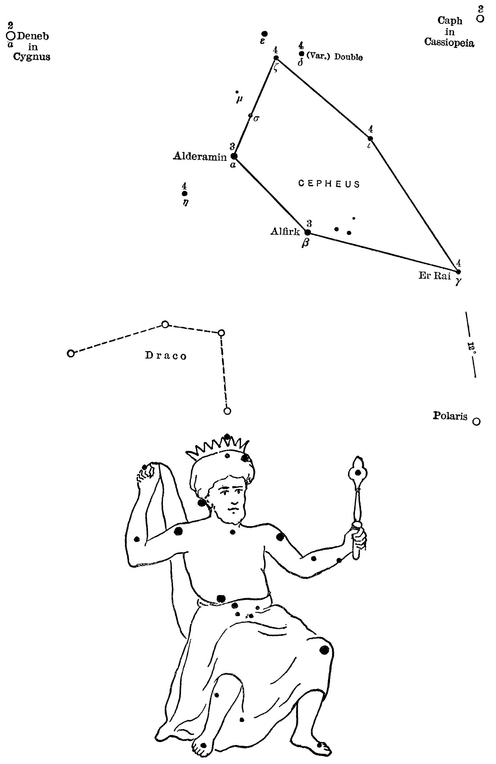

CEPHEUS

CEPHEUS

THE KING

Cepheus himself just behind Cynosura

Stands like one spreading both his arms abroad.

ARATOS.

ALTHOUGH one of the most inconspicuous constellations, Cepheus has attracted attention from the beginning of recorded history. It seems in a measure appropriate that Cepheus should be a dim constellation, for in the thrilling story of the rescue of Andromeda by the champion Perseus, Cepheus, the King, played but a subordinate part.

Plunket gives 3500 B.C. and 23 degrees north latitude as the approximate date and location of the people who invented this constellation. Allen says that Achilles Tatios, probably of our 5th century, claimed that Cepheus was known in Chaldea twenty-three centuries before our era, while according to Brown all of the circumpolar constellations originated on the eastern shores of the Mediterranean.

Cepheus is generally conceded to have been King of Æthiopia, the Euphratean “Cush,” the husband of Cassiopeia, and the father of Andromeda. There is a difference of opinion as to what language the names Cepheus and Cassiopeia are derived from. Some writers have suggested for their origin the Sanscrit names “Capuja,” which was the later Hindu name for Cepheus, and “Cas-syape.” Cepheus has also been identified with Cheops or Khufu the builder of the Great Pyramid in Egypt, and, again, was supposed to be descended from Iasion, the son of Zeus and Electra.

Cepheus and the constellations of the group with which he is generally associated are known as “the Royal Family.” They also comprise the so-called circumpolar constellations, and in these latitudes never set. They are especially noteworthy as illustrating the ancient legend of Perseus and Andromeda, one of the best known of all the classic myths and one that has survived all ages. It shows clearly that there was an effort made on the part of the inventor of these constellations to depict here on the imperishable scroll of heaven a drama that should survive all time. There is another such example, which we will come to later, of a like intent to connect a series of constellations, so that the stories that individually relate to each should in toto portray a complete history. It is as if each constellation was but an instalment of a serial story. This seems fairly good proof that some of the constellations, at least, were carefully thought out by one man, that design and not chance was responsible for their creation, and that the legends they represented antedated the invention of the several star groups.

Cepheus also figures as one of the Argonauts, the valiant band of heroes that sailed in the ship Argo in quest of the golden fleece, and was changed into a constellation at his death. Newton claims that all the ancient constellations relate in some way to this famous expedition. He argues that “as Musæus. one of the Argonauts, was the first Greek who made a celestial sphere, he would naturally delineate on it those figures which had some reference to the expedition. Accordingly, we have on our globes to this day, ‘the Golden Ram’ (Aries), the ensign of the ship in which Phryxus fled to Colchis, the scene of the Argonautic achievements. We have also the Bull (Taurus) with brazen hoofs tamed by Jason; the Twins (Gemini) Castor and Pollux; two sailors with their mother Leda in the form of a Swan (Cygnus); and Argo, the ship itself. The watchful Dragon (Draco) Hydra, with the Cup (Crater) of Medea, and a raven (Corvus) upon its carcass, as an emblem of death; also Chiron (Sagittarius), the master of Jason, with his ‘Altar’ and sacrifice. Hercules, the Argonaut, with his club, his dart (Sagitta), and vulture, with the Dragon, Crab (Cancer), and Lion (Leo) which he slew; and Orpheus, one of the company, with his harp (Lyra). Again we have Orion, the son of Neptune, or as some say the grandson of Minos, with his dogs (Canis Major and Minor), and the Hare (Lepus), River (Eridanus), and Scorpion. We have the story of Perseus, in the constellation of that name, as well as in Cassiopeia, Cepheus, Andromeda, and Cetus; that of Callisto and her son Arcas in Ursa Major; that of Icarius and his daughter Erigone in Boötes and Virgo. Ursa Minor relates to one of the nurses of Jupiter, Auriga to Erichthonius, Ophiuchus to Phorbas, Sagittarius to Crolus, the son of one of the Muses, Capricorn to Pan, and Aquarius to Ganymede. We have also Ariadne’s crown (Corona Borealis), Bellerophon’s horse (Pegasus), Neptune’s dolphin (Delphinus), Ganymede’s eagle (Aquila), Jupiter’s goat with her kids, the asses of Bacchus (in Cancer), the fishes of Venus and Cupid (Pisces), with their parent the Southern Fish.” These, according to Deltoton, comprise the Grecian constellations mentioned by the poet Aratos, and all relate, as Newton supposes, remotely or immediately to the Argonauts.

There is every reason to believe, however, that the constellations were invented long before the date of this famous expedition.

Allen tells us that in China, the Inner Throne of the Five Emperors was located somewhere in this constellation. One of the Chinese Emperors, it is said, ordered a group of stars in Cepheus to be called “Tsau-fu” after his favourite charioteer.

Cepheus had for the Arabs a pastoral significance. In fact in the Euphratean star list Cepheus signified “numerous flock.” The stars in the vicinity of the North Pole were supposed to represent a shepherd attended by his dog, watching a herd of sheep at pasture. Goats, calves, and camels also figure in the picture. These animals are all in the neighbourhood of Cepheus.

It is useless of course for us to try to see this picture as it appeared to those night watchers of the far East. Situated in an ideal region for star-gazing as regards climatic conditions, in a land where the nights were glorious with stars and where the people spent most of the nocturnal hours on the house tops or out on the hills, gifted with a wonderfully fertile imagination, it was but natural that they should adore the stars, the mystery of which appealed to their superstitious natures, and exalt their heroes to the starry skies. As they were deeply interested in the care of herds and flocks we naturally find that certain star groups represented to them pastoral scenes. These stellar pictures of the ancients are interesting as showing the changes wrought by the advance of progress and civilisation, and there must indeed have been a fascination in painting pictures on the widespread canvas of the night with a brush steeped in the bright-hued pigments of imagination.

Smyth alluded to the constellation Cepheus as “the Dog,” and a ring of stars in this group was known to the Arabs as “a Pot.”

Dr. Seiss claimed that C pheus represented the coming of the Redeemer as King, while Cæsius and Julius Schiller wished to substitute King Solomon and Saint Stephen for the time-honoured personage.

pheus represented the coming of the Redeemer as King, while Cæsius and Julius Schiller wished to substitute King Solomon and Saint Stephen for the time-honoured personage.

The Cepheid meteor shower of the 28th of June radiates from a point near γ Cephei, and the star μ Cephei is worth observing as being Sir William Herschel’s celebrated “Garnet Star,” one of the reddest stars in the sky, and a fine object in an opera-glass.

Surrounding the stars δ, ε, ζ, and λ Cephei, which mark the head of the King, is a vacant gap in the Milky Way, one of the so-called “Coal Sacks,” where no stars have been observed even in our most powerful telescopes.

Cepheus furnishes a good example of the fact that it is not always among the brightest constellations that the most interesting objects are found.

Its three brightest stars, α, β, and γ Cephei, gain a certain interest when it is known that by reason of the precession of the equinoxes these stars will one after the other take the place of the Pole Star of ages to come.

In 4500 A.D. γ Cephei will be Polaris. In 6000 A.D. β Cephei succeeds to the title, and 1500 years later α Cephei marks the Pole of the heavens. Only the last will be as near the true Pole as our present Pole star is now.

β Cephei is a beautiful double star, a fine object in a small telescope, and when observing it interest is added by the thought that the primary is also double, although too close to be seen visually, that wonderful instrument the spectroscope revealing its duplicity. This spectroscopic binary has an exceedingly rapid revolution, a complete circuit of the orbit taking less than five hours, which is the most rapid orbital revolution so far known.

The stars ξ and  Cephei are also fine doubles for a small telescope. For the naked eye observer there is situated in this constellation an object of great interest, the variable star δ Cephei, a typical example of a certain class of variable stars of short period, which are now called the Cepheid variables. Its changes in brightness are perfectly regular and it is an accurate time-keeper, successive maxima following one another at intervals of 5 days, 8 hours, 47 minutes, and 39 seconds. Unlike the so-called Algol variables its light changes are continuous without any period when the brightness is constant. The remarkable behaviour of this star furnishes one of the most puzzling problems of astro-physics. δ Cephei is easily visible to the naked eye and any one can watch these interesting variations in its magnitude. The range is from 3.7 to 4.9.

Cephei are also fine doubles for a small telescope. For the naked eye observer there is situated in this constellation an object of great interest, the variable star δ Cephei, a typical example of a certain class of variable stars of short period, which are now called the Cepheid variables. Its changes in brightness are perfectly regular and it is an accurate time-keeper, successive maxima following one another at intervals of 5 days, 8 hours, 47 minutes, and 39 seconds. Unlike the so-called Algol variables its light changes are continuous without any period when the brightness is constant. The remarkable behaviour of this star furnishes one of the most puzzling problems of astro-physics. δ Cephei is easily visible to the naked eye and any one can watch these interesting variations in its magnitude. The range is from 3.7 to 4.9.

α, β, and γ Cephei were known respectively by the Arab names “Alderamin,” meaning the “right arm,” “Alfirk,” “a flock,” and “Errai,” the “shepherd.”