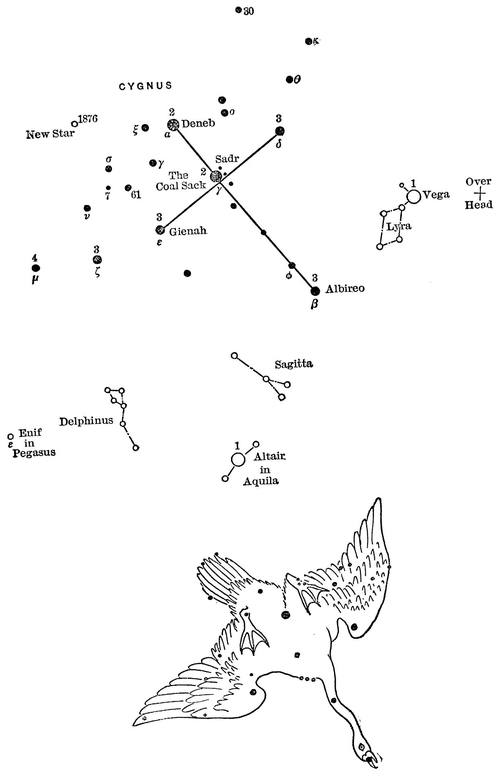

Cygnus The Swan or The Northern Cross

CYGNUS

CYGNUS

THE SWAN

OR

THE NORTHERN CROSS

Thee, silver Swan, who silent, can o’erpass ?

A hundred with seven radiant stars compose.

The graceful form: amid the lucid stream

Of the fair Milky Way.

EUDOSIA.

THERE are few constellations in the firmament that exceed in beauty and interest the star group popularly known as “the Northern Cross.” Shrouded in the glory of the Galaxy, rich in telescopic objects of exquisite beauty, famed in fable and song, this constellation possesses a charm that is enduring, a fascination for all students of the stars and lovers of the beautiful.

There are various legends to account for the presence of the Swan in the starry skies. One relates that the Swan represents Orpheus the wonderful musician, who won the beautiful Eurydice for his bride. Foully slain by the cruel priestess of Bacchus, Orpheus was changed into a swan and transported to the heavens, where he was placed near his beloved Harp (the constellation Lyra), possibly to add his mite to the sweet music of the spheres.

Others suppose it to be the swan into which Jupiter transformed himself when he deceived Leda, wife of Tyndarus, King of Sparta.

Again we are told that the Swan was Cicnus or Cycnus (and this is believed to be the proper name for the constellation), a son of Neptune, who was invulnerable to attack from blows or missiles. Achilles after striving in vain to wound Cicnus finally succeeded in smothering him. As he was about to rob his victim of his armour, Cicnus was suddenly changed into a swan.

According to Ovid, the constellation took its name from Cygnus, a relative of Phaëton’s, who deeply lamented the untimely fate of that youth, who was hurled into the river Eridanus after his disastrous ride. The legend relates that after Phaeton had disappeared beneath the waters of the river, Cygnus frequently plunged into the stream to seek him. The gods in wrath changed him into a swan, and therefore it is that the swan ever sails about in the most pensive manner, and frequently thrusts its head beneath the water.

Virgil in the roth Book of his Æneid thus alludes to this fable:

For Cicnus loved unhappy Phaeton,

And sung his loss in poplar groves alone,

Beneath the sister shades to soothe his grief.

Heaven heard his song and hastened his relief,

And changed to snowy plumes his hoary hair,

And winged his flight to sing aloft in air.

Allen tells us that this constellation may have originated on the Euphrates, for the tablets show a stellar bird of some kind. At all events the present figure did not originate with the Greeks, for the history of the constellation had been entirely lost to them.

In Arabia Cygnus was called “the Flying Eagle,” and “the Hen,” appearing under the latter title about 300 B.C. in Egypt.

Cygnus is generally represented in full flight along the Milky Way.

Yonder goes Cygnus the Swan, flying southward.

On some old maps the bird is apparently just rising from the ground. Aratos describes the Swan:

As one that floats on well poised wings.

In the Euphratean star list this constellation bears the title of “Bird of the Forest.”

Before the time of Eratosthenes (the third century B.C.) the name of the star group among the Greeks was simply “the Bird.”

This portion of the sky seems to abound with birds,—as if they hovered over the region of the heavens known to the ancients as “the Sea.” Here we find besides the Swan, Aquila the Eagle, the flying Eagle, and Lyra, which was regarded as the falling or swooping Eagle.

Sayce states that the Assyrian name of the Swan is supposed to be “Tussu,” while Houghton has been unable to discover any Hebrew, Assyrian, or Phoenician name for the constellation.

The brightest stars in Cygnus form the so-called “Northern Cross,” a perfect and beautiful figure, which Lowell thus alludes to in his poem, “New Year’s Eve, 1844” :

and countless splendours more

Crowned by the blazing Cross high hung o’er all.

The Cross is formed by the stars α, ϒ,  , β, Cygni, marking the upright along the Milky Way, more than twenty degrees in length, and ξ, ε, ϒ, δ Cygni, forming the transverse.

, β, Cygni, marking the upright along the Milky Way, more than twenty degrees in length, and ξ, ε, ϒ, δ Cygni, forming the transverse.

The early Christians regarded this figure as the Cross of Calvary, as did Schiller. The Northern Cross is certainly much more perfect in form than the famed Southern Cross, and setting in the west, when it assumes an upright position, it presents a beautiful appearance.

Christmas eve at nine o’clock, this brilliant cross of stars stands upright on the western hills, outlined against the sky as if beckoning all beholders onward and upward. A beautiful symbol of the Christian faith, glorious, perfect, and eternal, and especially significant at this season of the year.

Between α, ϒ, and ε Cygni is one of the vacant spaces in the Milky Way, a black and seemingly bottomless abyss, the brink over which man peers into the profound and mysterious depths of interstellar space. This wonderful region in the sky is known as “the Northern Coal Sack.”

Cygnus is celebrated as containing the nearest lucid star in the northern hemisphere, a 5.6 magnitude star, barely visible to the naked eye, known as “61 Cygni.” It is a double star, both being golden yellow in colour, situated six degrees north and east of the star ε Cygni. Bessel, in 1838, calculated its distance as approximately six light years,—a light year being the distance light travels in a year at the rate of 186,000 miles a second. 61 Cygni bears the distinction of being the first star whose distance was measured. If the distance from the earth to the sun equals one inch, the distance from the earth to 61 Cygni would equal seven and one half miles. This gives one a good idea of star distances, which to all intents and purposes are beyond our comprehension. To illustrate the amount of labour bestowed by astronomers on the problem of the determination of star distances, it may be mentioned that for the photographic measure of the star 61 Cygni, 330 separate plates were taken in the year 1886-7. On these, thirty thousand measurements were made. The result agreed closely with the best previous determination by Sir Robt. Ball, using the micrometer.

The lucida of the constellation is Alpha Cygni, called by the Arabs “Deneb,” meaning the “Hen’s Tail.” It is a brilliant white 1.4 magnitude star, comparatively young, and in the same spectroscopic class as Spica and Vega. The spectroscope reveals that Deneb is approaching the earth at the rate of thirty miles a second. From the best determinations Deneb is at least ten times as far off as Vega. The distance of Vega is thus expressed: Supposing the sun’s distance from the earth (93,000,000 miles) equals one foot, Vega is 158 miles distant. This puts Deneb at a reasonably safe distance from us.20

Deneb can be seen at some time between sunset and midnight every night in the year in these latitudes. Mrs. Martin pays it this charming tribute: “Deneb is particularly attractive in the early evening in January and February. It is then rather low in the north-west and with Vega gone, and no other bright star very near, it has a more commanding charm. In the heavier atmosphere which induces a more rapid twinkling, the star seems to take on an accession of gaiety, and goes fairly dancing down behind the horizon, where it finishes its circle and appears again in the north-east about four hours later.”

Deneb culminates at 9 P.M., Sept. 16th.

Cygnus is a splendid field for telescopes, great and small. Its chief object of beauty is the incomparably beautiful double star, Beta Cygni, also known as “Albireo,” situated in the base of the Cross and in the beak of the Swan. Even in a small telescope the contrast in the colours of these two close set stars is well emphasised, and the sight of these suns, the one gold, the other blue, never fails to charm all who view them. As this double is easily split by small telescopes, Albireo is a great favourite with all amateur astronomers.

Cygnus contains many deeply coloured red and orange stars, and Birmingham called this part of the heavens “the Red Region,” or “the Red Region of Cygnus.”

Espin gives a list of one hundred stars in this constellation that are double, triple, or multiple.

The 2.7 magnitude star ϒ Cygni was called “Sadr” by the Arabs, meaning the “Hen’s Breast.” Allen says, “it lies in the midst of a beautiful stream of small stars, itself being involved in a diffused nebulosity extending to α Cygni, while the space from ϒ to β Cygni is perhaps richer than any of similar extent in the heavens.” In this space, according to Herschel, the stars in the Milky Way seem to be clustering into two separate divisions, each division containing more than 165,000 stars. So rich is this region of the heavens in stars, that Herschel counted 331,000 in a width of only five degrees.

In the neck of the Swan, not far from Beta Cygni, is the variable star χ Cygni, discovered by Kirch in 1686, ranging from magnitudes 4.5 to 13.5 in 406 days. Sometimes at its maximum it reaches only the sixth magnitude, thus presenting a problem which is one of the most interesting in all the realm of astrophysics.