Hydra

The Water Snake

HYDRA

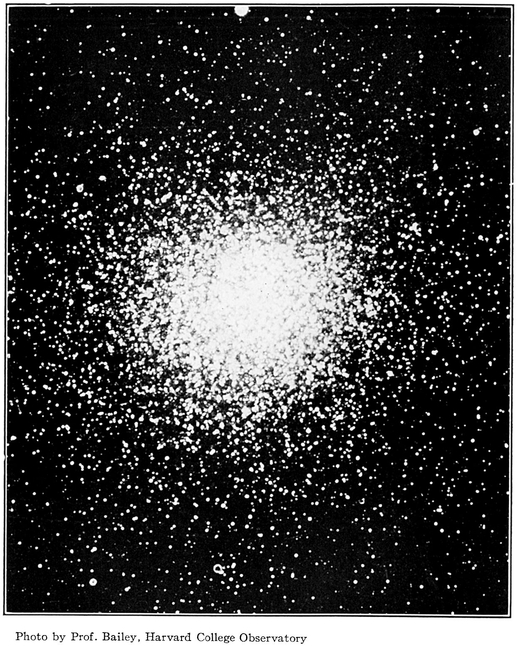

Star Cluster in Centauri

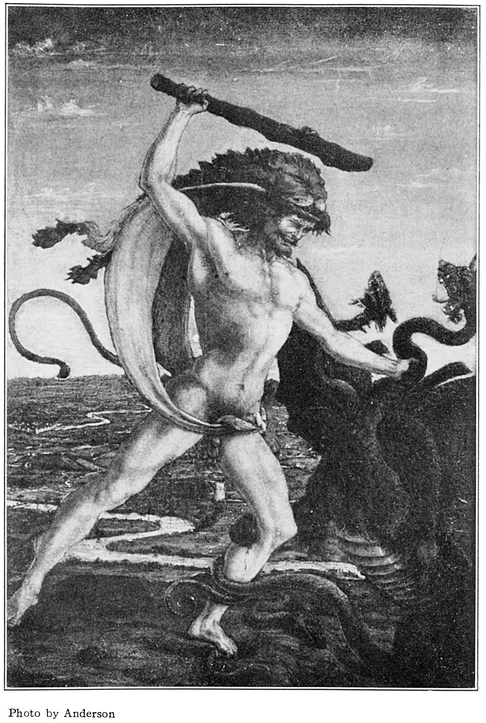

Hercules and the Hydra Uffizi Gallery at Florence

HYDRA

THE WATER SNAKE

But lo: afar another constellation,

They call it Hydra like a living creature.

’Tis long drawn out. His head moves on below

The midst of the Crab; his length below the Lion,

His tail hangs o’er the Centaur’s self.

FROTHINGHAM’S Aratos.

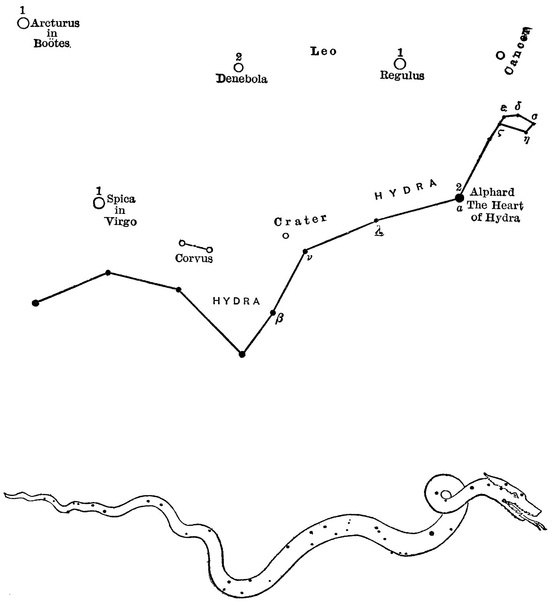

BURRITT’S chart represents Hydra as bearing on his coils, as he draws himself along the sky, a Cup, and two birds, the Crow and the Owl, the latter being a recently added asterism. His fierce head and extended fangs seem dangerously close to the Lesser Dog, while the Crab, just above him, lies in wait to seize him in its vice-like claws.

Hydra is supposed to be the snake shown on a uranographic stone from the Euphrates of 1200 B.C., “identified with the source of the fountains of the great deep,” and one of the several sky symbols of the great dragon Tiamat. On one of the Euphratean boundary stones, those most ancient records of early times, the figures of the Water Snake and the Scorpion appear side by side.

Brown claims that Hydra is a variant reduplication of Cetus, the storm and ocean monster attacked by the sun-god, and in an ancient Akkadian hymn it is referred to as bearing the yoke on its seven heads.

The ancients perceived an analogy between a quick flowing river, and the swift gliding of a huge glistening serpent, and so, as Maunder says, we arrive at the idea of the River of the Snake, which develops into an ocean stream. The Egyptians at one time regarded this constellation as the celestial counterpart of the River Nile. It has also been identified with the Argonautic constellations.

In Greek mythology Hydra was the Lernæan monster, a great water snake, destroyed by the famous Hercules as the second labour imposed on him. It is related that this fierce serpent lived in a swamp near the well of Amy-mone, and was wont to ravage the country of Argos. The monster had one hundred heads according to Diodorus, fifty according to Simonides, and nine according to the more commonly received opinion of Apollodorus, Hyginus, and others. The head in the centre was said to be immortal. As fast as Hercules struck off one of the monster’s heads with his club two new ones appeared in its place, and the task of slaying the monster appeared hopeless. At this juncture, the legend relates, Iolaus, the faithful nephew of Hercules, came to his assistance, and suggested burning off the heads of the serpent. This they successfully accomplished, and the ninth head which was immortal they buried under a rock. Hercules then dipped his arrows in the Hydra’s blood, which ever after rendered mortal the wounds they inflicted.

Juno, jealous of the success of Hercules, sent a sea crab to bite his foot while he was engaged in slaying the Hydra, but the giant easily disposed of the crustacean, much to Juno’s disgust.

This myth connects Hydra with the Crab, a relation which, owing to their proximity in the sky, would seem to call for an explanation.

Burritt claims that this fable of the many-headed Hydra may be understood to mean nothing more than that the marshes of Lerna were infested with a multitude of serpents, which seemed to multiply as fast as they were destroyed.

Among the constellations we find the figures of three serpents. At the present time their position in the heavens does not appear especially significant, but in order to understand in a measure the history of the constellations, we must endeavour to see the heavens as viewed by the ancients who designed them.

By reason of the Precession of the Equinoxes, that slow change in the position of the heavens, which is constantly going on, the constellations bore different relations to the important points in the heavens than they do now. A Precessional globe enables us to see the star groups as they appeared at any period, and taking the date Maunder suggests, 2700 B.C., as the approximate time when the constellations were designed, and 40 degrees north latitude as the probable abode of those who planned them, we find in the grouping of the serpentine constellational figures several significant facts. The far-extended Hydra crawls along his full length, “going on his belly.” The Serpent clasped tightly in the hands of the giant Ophiuchus writhes upward in his struggle to escape, while the Dragon, the great serpent of the north, twines around the crown of the sky, as if guarding the Pole.

Again Hydra lay at this time along the equator, taking seven hours out of the twenty-four to cross the meridian. The Serpent marked the intersection of the equator with one of the principal meridians of the sky, while the Dragon of the north linked the north pole of the celestial equator to the north pole of the ecliptic,

These facts seem significant, and tend to show that there was a definite plan in the minds of those who designed these star groups.

Further, Draco was supposed to represent the oblique course of the stars, while Hydra, the great southern serpent, symbolised the moon’s course.

Hydra has been identified with the Flood, the River Jordan, and Plunket claims that it represents the demon Vrita, of the Rig-Veda, conquered by India. Between the first magnitude stars Procyon and Regulus, and between the ecliptic and equator, there is a group of stars in Hydra marking the head of the creature, a striking and conspicuous group, forming a rhomboidal figure. These stars were called by the Chinese “the Willow Branch,” or “Circular Garland,” which rules over planets, and forms the beak of the “Red Bird.” It was worshipped at festivals of the summer solstice as an emblem of immortality.

Here, too, Allen tells us was the seventh Hindu lunar station, known as the “Embracer,” which was figured as a wheel. Edkins asserts that this star group was also known as “the Seven Stars.” In the Euphratean star list it bears the title of “the Mouth of the Snake Drinks.”

According to Dr. Seiss, the Hydra stands for that Old Serpent called the Devil, while to Schiller it represented the River Jordan.

The only star of importance in this constellation is the second magnitude star α Hydræ, a dull red star known to the Arabs as “Alphard,” meaning the “solitary one,” an appropriate title as there are no other bright stars in this region of the heavens. Tycho Brahe was the first to call it “Cor Hydræ,” the heart of Hydra, a familiar name for the star. The Arabs also knew it as “the Backbone of the Serpent,” and it was the most prominent star in the great Chinese asterism called “the Red Bird.” Alphard culminates at 9 P. M. on March 26th.

Eudosia thus alludes to Hydra and the star Alphard:

... Near the equator rolls

The sparkling Hydra, proudly eminent

To drink the Galaxy’s refulgent sea;

Nearly a fourth of the encircling curve

Which girds the ecliptic, his vast folds involve;

Yet ten the number of his stars diffused

O’er the long track of his enormous spires;

Chief beams his breast, sure of the second rank,

But emulous to gain the first.

Garrett P. Serviss, who has done so much to popularise astronomy, writes as follows of the stars like Alphard lone and unattended: “There is an attraction about these solitary bright stars that is almost mystical, their very loneliness lending interest to the view, as when one watches some distant snow-clad peak gleaming in the rays of sunset after all the lower mountains have sunk into the blue shadows of coming night.”

The star ε Hydræ presents a paradox. It is a double star. The brighter star, of the third magnitude, is sixteen times brighter than its companion, yet the fainter star has six times the mass of the brighter.