Orion

The Giant Hunter

ORION

ORION

THE GIANT HUNTER

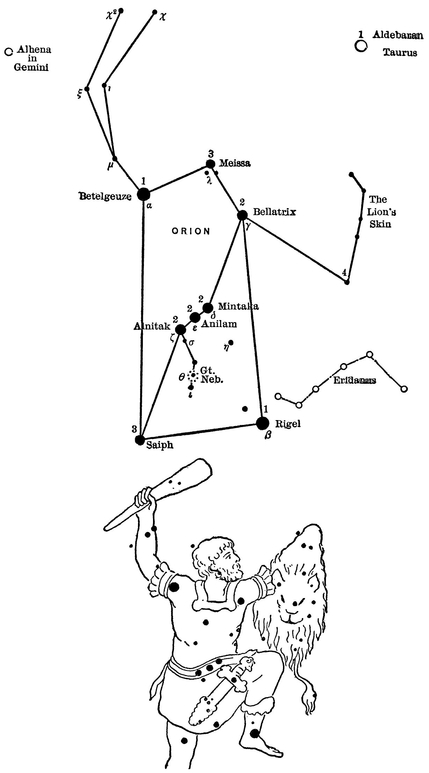

Orion kneeling in his starry niche.

LOWELL.

THE constellation Orion has been the admiration of all ages, and vies with Ursa Major and the famous Pleiades in historical and mythological interest. It is beyond question the most brilliant of the constellations, containing as it does two stars of the first magnitude, and four of the second. With the exception of the “Dipper,” the so-called “Belt of Orion” is probably the best known and most popular of all stellar objects.

The constellation is visible from every part of the globe, and the poets of all nations have sung its praises. Manilius pays the following tribute to the mighty hunter:

Now near the twins behold Orion rise,

His arms extended measure half the skies:

His stride no less. Onward with steady face,

He treads the boundless realms of starry space,

On each broad shoulder a bright gem displayed

While three obliquely grace his mighty blade.

And again he sings:

Orion’s beams, Orion’s beams:

His star gemmed belt and shining blade

His isles of light, his silver streams,

And glowing gulfs of mystic shade.

Shelley in his Revolt of Islam wrote:

While far Orion o’er the waves did walk

That flow among the isles.

Lucy Larcom contributes:

Orion with his glittering belt and sword

Gilded since time has been, while time shall be.

And Longfellow thus alludes to this beautiful constellation:

Begirt with many a blazing star

Stood the great giant Algebar

Orion, hunter of the beast,

His sword hung gleaming by his side.

Hesiod wrote:

When strong Orion chases to the deep the Virgin stars.

Tennyson refers to the constellation in his Locksley Hall, Maud, and The Princess, and Spenser describes the setting of Orion in these words :

And now in ocean deep

Orion flying fast from hissing snake

His flaming head did hasten for to steep.

Much doubt and mystery surround the title of the constellation. Brown, one of the most reliable authorities, is of the opinion that it is from “ Uru-anna, ” meaning the “light of heaven,” and that the title originated in the Euphratean Valley.

It seems reasonably certain that a star group of such prominence should have attracted attention from the earliest times, and that this constellation therefore is of great antiquity.

Maunder tells us that the word from which Orion was derived was “ Kesil, ” a word which occurs in an astronomical sense four times in the Bible. The Hebrew word “ Kesil” signifies “a fool,” meaning a godless and impious person. In the Scriptures this word is associated with a word which, translated, refers to the Pleiades, sometimes likened to a flock of doves.

We have, therefore, in the figure of Orion, a mighty giant represented as trampling on a timid hare, and pursuing a flock of inoffensive doves, certainly a strange and incongruous association of figures.

Maunder claims that it was intense irony for the Hebrews to designate as “a fool” the constellation that the Babylonians had deified, and made their supreme god, and styled “the Mighty Hunter.”

Orion has been identified with Merodach, probably the first King of Babylonia, and with the Nimrod of the Scriptures, “the mighty hunter before the Lord,” known also as “the mighty one in the earth,” a variant of Merodach.

Several Assyriologists consider that the constellations Orion and Cetus represent the struggle between Merodach and Tiamat. In support of this view, it may be said that Tiamat is expressly identified on a Babylonian tablet with a constellation near the ecliptic.

Maunder thinks that the view that has come down to us through the Greeks concerning Orion agrees much better with the associations of the constellations as held among the Hebrews rather than amongst the Babylonians. According to the Greek legend, Orion pursued the Pleiades, which were considered doves or virgins, and was confronted by the Bull. Cetus was not involved in the struggle, but was engaged in a combat with Perseus.

There is in the threatening attitude of the Mighty Hunter as he stands facing the advancing Bull, carrying to ward off an attack, and his club raised to strike a blow, every indication of an attempt on the part of the inventor of the constellation to indicate a conflict to the death between Orion and the Bull.

... on his arm the lion’s hide,

The figure of the Hare crouching beneath the Hunter’s foot is also significant. The hare has always been associated in folk-lore with the moon, and as Brown points out, Orion as “the light of heaven” is clearly identified with the sun. Here we have, many think, a figure symbolical of the perpetual strife between the powers of light and darkness, in which the former ever prevails.

Plunket claims 4667 B.C. as the date of the invention of this constellation. Orion at that time accurately marked the equinoctial colure, but others have thought that 2000 B.C. was the more probable date, as at that time the so-called “Belt of Orion” began to be visible before dawn in the month of June, called “ Tammuz, ” and Orion was known to the Chaldeans as “Tammuz.”

As the death of Adonis is celebrated in the month Tammuz, Miss Clerke is of the opinion that Orion received this name because its annual emergence from the solar beams coincided with the mystical mourning for the vernal sun. “Altogether the evidence is strong,” says Miss Clerke, “that Orion may be considered as a variant of Adonis, imported into Greece from the East at an early date, and there associated with the identical group of stars which commemorated to the Akkads of old, the fate of Tammuz, the ‘only Son of Heaven.’”

Homer describes Orion as the “tallest and most beautiful man,” which description well befits Adonis.

According to Brown, Orion like Boötes was regarded as a shepherd, the keeper of the flock of stars, and one of his titles was “Shepherd Spirit of Heaven.”

Orion was also known as “the Lord of the River Bank,” an appropriate name as regards his location close by Eridanus, the River Po.

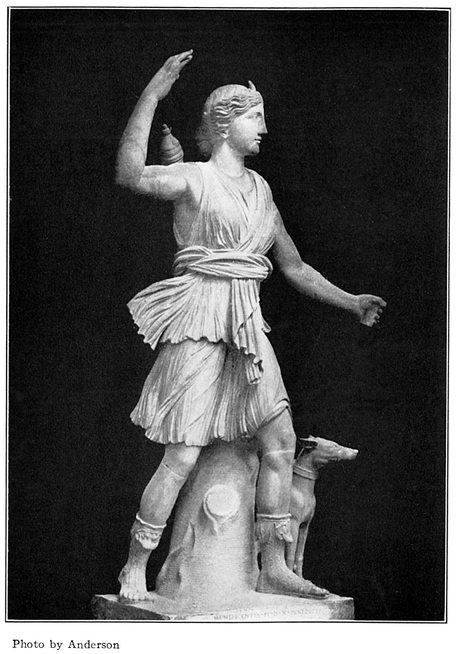

In mythology Orion is connected with the constellation of the Scorpion, and it is related that Orion boasted that there was not an animal on earth which he could not conquer. To punish his vanity, it is said, a scorpion sprang out of the earth and bit his foot, causing his death. At the request of Diana he was placed among the stars opposite his slayer.

Ovid agrees with this version, but Hyginus, Homer, and Apollodorus claim that Orion was killed by Diana’s darts, and that he was placed in the sky opposite the Scorpion so that “he might escape in the West as the reptile rose in the East.”

When the Scorpion comes

Orion flees to utmost end of earth.

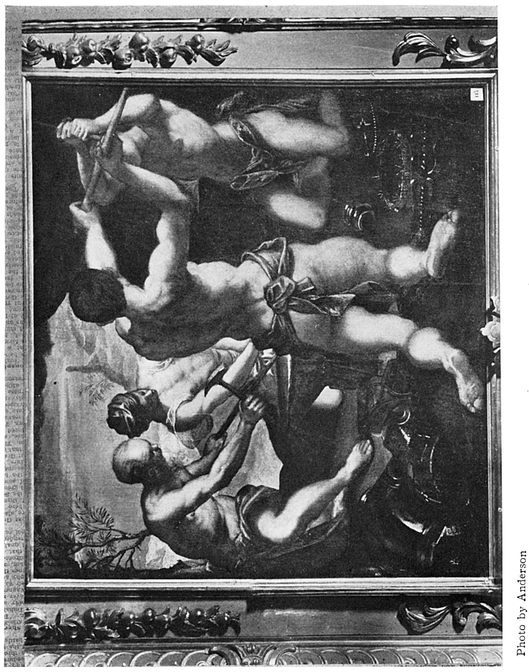

The Forge of Vulcan In the Ducal Palace, Venice

Diana

Capitoline Museum, Rome

The Hindus connect in a legend, Aldebaran, the red star in the eye of the Bull, Sirius, known to them as “the Deerslayer,” and Orion, which they regard as “a Stag.” The story is as follows: “The Lord of created beings fell in love with his daughter. She took the form of a dove and fled. He thereupon changed himself into a stag and pursued her, but was shot by Sirius, who was selected by the indignant gods to slay him.”

The three stars in the head of the Mighty Hunter constitute one of the Hindu lunar stations known as “the antelope’s head,” in accordance with this myth.

Another legend concerning Orion relates that he was the lover of Merope, daughter of Œnopion, King of Chios. His suit was frowned upon, so he attempted to elope with the fair object of his affections. The King, however, discovered his perfidy, and drugging him, put out his eyes, and left him alone on the seashore. Following the sound of a hammer, Orion, it is said, made his way to the forge of Vulcan, where he besought assistance. Vulcan placed him on the shoulders of a Cyclops, who carried him to the top of a mountain, where, facing the rising sun, he received his sight.

. . .he

Reeled as of yore beside the sea

When blinded by Œnopion.

He sought the blacksmith at his forge

And climbing up the narrow gorge

Fixed his blank eyes upon the sun.

Longfellow.

This legend connects Orion with the Sun-god, and the title he sometimes bears, “Light of Heaven.”

There is an analogous myth of the moon-goddess connected with Orion: The moon-goddess fell in love with the Giant Hunter. The sun-god did not approve of him, and resolved to bring about his destruction. As Orion was bathing, the sun-god poured his golden rays upon him, and called on the moon-goddess to test her skill in archery by shooting at the gleaming mark. The moon-goddess winged a shaft, and slew Orion, her lover, hidden in the brilliant light. Distracted she appealed to Jove, who placed Orion in the sky so that the moon-goddess might gaze upon him as she sails in her silver chariot.

Still another story relates that Orion was born like Athena without a mother, and became a famous iron worker, so skillful that Vulcan employed him to build a palace under the sea.

Orion was always regarded as a stormy constellation from the fact of its setting in the late autumn. Thus Æneas accounts for the storm which cast him on the African coast, on his way to Italy:

To that blest shore we steer’d our destined way

When suddenly dire Orion rous’d the sea.

Again we read:

Tell him that charg’d with deluges of rain

Orion rages on the wintry main.

The constellation’s stormy character, says Allen, appeared in early Hindu, and perhaps even in earlier Euphratean days, and is seen everywhere among classical writers, with allusions to its direful influence.

Polybios, the Greek historian of the second century before Christ, attributed the loss of the Roman squadron in the first Punic War to its having sailed just after “the rising of Orion.”

Hesiod long before wrote of the same rising:

then the winds war loud,

And veil the ocean with a sable cloud.

And Milton wrote:

When with fierce winds Orion arrived

Hath vexed the Red Sea coast.

Hesiod also lays it down that the rising of Orion is the season for threshing:

Forget not when Orion first appears

To make your servants thresh the sacred ears;

and points to the time when Orion is in the mid-heavens as proper for the vintage. He also directs the husbandmen to plough at the setting of this constellation, and warns navigators to avoid the dangers of the sea, when the Pleiades, flying from Orion, are lost in the waves.

The Syrians and Arabians knew Orion as “the Giant.” To the early Arabs, Orion was “Al-Jauzah,” often erroneously translated “Giant,” says Allen. Originally this was the term used for a black sheep with a white spot in the middle of the body, and this may have become the designation for the middle figure of the heavens, which, from its pre-eminent brilliancy, always has been a centre of attraction.

In Egypt, the soul of Osiris was said to rest in the constellation Orion, and in the round zodiac of the temple of Denderah there is a mythological figure of a cow in a boat identified as Sirius, and near it another mythological figure which has been proved, according to Lockyer, to represent the constellation Orion.

Allen says that the Egyptians represented Orion as Horus, the young or rising sun, in a boat surmounted by stars, and as “Sahu” in the great Ramesseum of Thebes, about 3285 B.C.

Orion was an extremely important constellation in Egypt, because it preceded and announced the approaching rise of Sirius, which in turn heralded the inundation of the Nile.

According to a Jewish tradition, this constellation was appropriated to himself by a particularly mighty man. The Hebrews knew Orion as “the Giant,” bound to the sky for rebellion against Jehovah, and Allen thinks that this may be the explanation of the well-known phrase “the Bands or Bonds of Orion.”

The Chinese called Orion “Tsan,” which signifies “Three,”and corresponds to the “ Three Kings,” a title sometimes applied to the three prominent stars in the “Belt.” It The Chinese also knew Orion as ”the White Tiger,“a title taken from the constellation Taurus, close to Orion.

The Eskimos called Orion’s Belt “Tua Tsan,” a title similar to the Chinese title, which might indicate that the Eskimos originally came from China as has often been contended.

The Eskimos thought that Orion represented a party of bear-hunters, with their sledge, and the bear they were pursuing, transported to the sky.

According to Dr. Seiss, Orion stands as a prophetic representation of the great enemy and destroyer, death.

The early inhabitants of Ireland called Orion “the armed King, ” and the Mayas, the ancient inhabitants of Yucatan, knew the constellation as “a Warrior,” a further instance of a similarity in stellar nomenclature among widely separated nations, a similarity that is so marked and so often encountered as to disprove any idea of mere coincidence.

“The rising of Orion is one of the most imposing spectacles that the heavens afford,” says Serviss. “No constellation compares with it in brilliance. It is wonderfully rich in telescopic objects of interest, and Flammarion calls it ‘the California of the Sky.”’

Mrs. Martin says the group exacts more immediate admiration because the bright stars are “ clustered so closely and symmetrically as to form a set figure of dazzling jewels, a veritable sunburst of diamonds in the sky.”

There is much of interest concerning the individual stars in this constellation. α Orionis was known to the Arabs as “Betelgeuze,” an abbreviation for “the armpit of the central one.”It is an irregular variable star of a rich topaz hue, and is often called “the Martial Star. ”

The Zodiac of Denderah

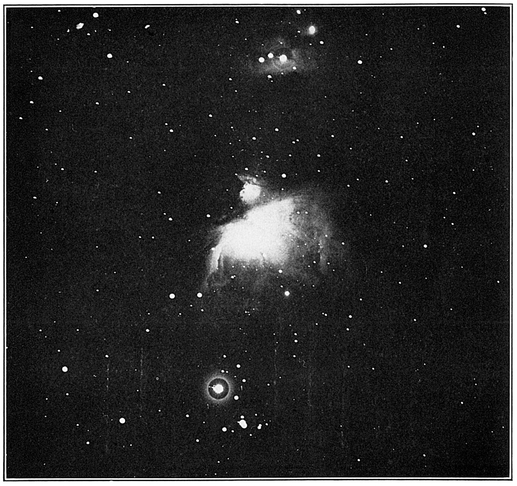

Great Nebula in Orion Harvard College Observatory

...First in rank

The martial star upon the shoulder flames.

In astrology this star denoted military or civic honours.

Mrs. Martin describes Betelgeuze as “suggestive of sombreness in its dull and comparatively untwinkling face.”

Allen tells us that the title “Roarer” or “Announcer” is also applied to this star, as heralding the rising of its companions.

Betelgeuze marks the 6th Hindu lunar station known as “Ardra,” meaning “moist.” In this title we see an allusion to the stormy character of the constellation, and when this star rose the rainy season set in.

Sayce and Bosanquet identify Betelgeuze with the Euphratean “Gula,” and Brown says the constellation of “the King” or “Ungal” refers to α, γ, and λ Orionis. In the Euphratean star list we find Betelgeuze styled “Lugal” (the King). The similarity in these titles “Gula,” “Ungal” and “Lugal” is strikingly suggestive.

Secchi makes Betelgeuze a typical star of his third class with banded spectra, suggesting that it may be approaching the point of extinction. According to Vogel it is receding from our system at the rate of 10.5 miles a second, and culminates at 9 P.M. Jan. 29th.

β Orionis is known to us as “Rigel,” the Arab title from which it came meaning “the left leg of the Jauzah, or Giant.” Another name for it is “Algebar,” a corruption of “Al-Jabbah,” the “mighty one.” It is a brilliant white star, and ranks fifth in order of brightness of all the stars visible in this latitude.

In astrology Rigel denotes splendours and honours.

In the Norseland, Rigel marked out the great toe of Orwandil, the other toe having been broken off by the god Thor, when frost-bitten, and thrown to the northern sky, where it became the little star Alcor in the handle of “the Dipper. ”

Rigel is receding from our system at the rate of ten miles a second. Newcomb estimated that it exceeds our sun in brilliance not less than ten thousand times. It is a double star, the companion being of the ninth magnitude, and blue in colour, but it is difficult to glimpse in a small telescope owing to the lustre of its primary.

γ Orionis is known as “Bellatrix,” the “Female Warrior,” and “the Amazon Star.” It is pale yellow in colour, and of the second magnitude. One Arab title for it was “the Roaring Conqueror,” or “the Conquering Lion.” It marks the left shoulder of the Giant.

Allen tells us that in an Amazon River myth, Bellatrix figures as a young boy in a canoe with an old man, represented by the star Betelgeuze. They are said to be chasing the Peixie Boi, a dark spot in the sky near Orion.

In astrology Bellatrix was the natal star of all destined to great civil or military honours, and rendered all women born under its influence lucky and loquacious.

It is said to be receding from our system at the rate of five miles a second.

The three so-called “Belt Stars,” of the second magnitude, in the centre of the parallelogram which renders the constellation conspicuous, have excited the attention of all ages, and many have been the titles bestowed on them. They are δ, ε, and ζ Orionis, and bear the Arab names, “Mintaka,” the “Belt,” “Alnilam,” the “String of Pearls” and “Alnitak,” the “Girdle,” respectively.

δ Orionis is a double star, 23’ of arc south of the celestial equator. ε Orionis is a leading example of stars of the hottest class. Its temperature has been estimated to be 45,000 degrees F.

In astrology these three stars portended good fortune and public honours. Job’s name for them was “the Bands of Orion,” while the Arabs knew them as “ the Golden Nuts,” or “ the String of Pearls.” The fierce Masai African tribe regarded these stars and those representing the sword of Orion, hanging from the Belt, as “three old widows following up three old men. ”

The Basuto tribe called the Belt stars “Three Pigs.” They have also been known as “the Three Kings,” “the Ell,” and “the Yard,” on account of the line joining them being just three degrees long.

Tennyson thus refers to these stars:

Those three stars of the airy Giant’s zone

That glitter burnished by the frosty dark.

The Germans designated them “Jacobstaff,” “the Staff of St. James,” and “the Three Mowers.”

The Chinese knew them as “a weighing beam,” with the stars in the sword as a weight at one end.

The Greenlanders called them “the Seal Hunters,” bewildered when lost at sea, and transferred together to the sky; and to the Eskimos these stars represented the three steps cut in a steep snow bank by some celestial Eskimo to enable him to reach the top.

The early Hindus called these stars “the three-jointed arrow,” and the native Australians regarded them as “ young men dancing. ”

In comparatively modern times, 1807, the University of Leipsic, disregarding all ancient appellations, christened these famous stars “Napoleon.” An Englishman retaliated by calling them “Nelson,” but these names have not been recognised by the world at large, nor do they appear on star maps or globes.

Seamen have called these stars “the Golden Yard Arm.”

Tennyson simply referred to them as “the three stars.”

In mythology they represent the arrow that despatched Orion. Other names for them are “The Rake,” “the Three Marys,” and “Our Lady’s Wand.”

A line drawn through them and prolonged southward passes near the brilliant and famous Sirius.25

Three fainter stars in this constellation have also attracted world-wide attention. They form a small triangle and are located in the head of the mighty hunter. The brightest is λ Orionis, a double star. Its Arab name, “Meissa,” means “the Head of the Giant.” The original name for the star, says Allen, meant “ a white spot.”

In astrology these three stars were unfortunate in their influence on human affairs. They constituted the Euphratean lunar station known as “the Little Twins,” and the Hindu station called “the Head of the Stag.”

In China these stars were known as “the Head of the Tiger. ” Manilius thus refers to them:

In the vast head immerst in boundless spheres

Three stars less bright but yet as great he bears,

But further off remov’d, their splendours lost.

Colas mentions an interesting fact in connection with the triangle formed by these stars, which reveals a current optical delusion. No ordinary observer would imagine that the moon could be contained in this triangle, but such is the fact, for the moon, which to the uninstructed observer appears about the size of “a dinner plate,” should be seen as a circle a half-inch in diameter fifty-seven inches away.

σ Orionis is a glorious multiple star, possibly the finest example of its type.

Serviss in his delightful book, The Pleasures of the Telescope , thus extols the praises of σ Orionis: “He must be a person of indifferent mind who after looking with unassisted eyes at the modest glimmering of this little star, can see it as the telescope reveals it without a thrill of wonder and a cry of pleasure. The glass, as by a touch of magic, changes it from one into eight or ten stars, and these stars exhibit a variety of beautiful colours charming to behold. However we look at them, there is an appearance of association among these stars, shining with their contrasted colours and their various degrees of brilliance, which is significant of diversity of conditions and circumstances under which the suns and worlds beyond the solar walk exist.”

It remains to mention what is probably the most interesting telescopic object, and certainly the most satisfactory to view of its kind in all the heavens, the Great Nebula in Orion. It is situated in the so-called “Sword” of the Giant which hangs pendent from the Belt, and surrounds the star θ Orionis. No description can give an adequate picture of the sight of this wonderful object even in a small telescope. The star θ is divided by the telescope into six stars, four of which can be seen with fairly low power, and compose the well-known “Trapezium.”

The nebula itself covers a space equal to the apparent size of the moon, but nebulosity extends over a much greater area. Its spectrum is purely gaseous, and its mass is said to be 4.5 million times that of the sun.

Serviss thus refers to it: “Nowhere else in the heavens is the architecture of a nebula so clearly displayed. It is an unfinished temple whose gigantic dimensions, while exalting the imagination, proclaim the omnipotence of its builder. But though unfinished it is not abandoned. The work of creation is proceeding within its precincts. There are stars apparently completed, shining like gems just dropped from the hand of the polisher, and around them are masses, eddies, currents, and swirls of nebulous matter yet to be condensed, compacted, and constructed into suns. It is an education in the nebular theory of the universe merely to look at this spot with a good telescope. If we do not gaze at it long and wistfully, and return to it many times with unflagging interest, we may be certain that there is not the making of an astronomer in us. ”

A fitting conclusion to this sketch of Orion and its stars, is a quotation from Mrs. Martin’s Friendly Stars respecting the constellation : “With all its wonders and its beauties it is not strange that Orion should be one of the most familiar and most admired of all the constellations. It is in the centre of the Galaxy that marches in brilliant procession across the winter skies. We watch for it between nine and ten o‘clock in the evening late in October, and our first view is of the curved line of faint twinkling stars that outline the left arm and the lion’s skin.

Then one jewel after another emerges from the storehouse below the horizon until the whole splendid figure is before us. Its arrival is an announcement that the outdoor season is past and that the nights are becoming more and more frosty and that the gorgeous tapestry with which the autumn hills seem covered will soon fade away and give place to the lovely low tones of winter. ”