Ursa Major

The Greater Bear

URSA MAJOR

URSA MAJOR

THE GREATER BEAR

He who would scan the figured skies

Their brightest gems to tell

Must first direct his mind’s eye north

And learn the Bear’s stars well.

URSA MAJOR, or the Greater Bear, is the most easily recognised and the most widely known of all the constellations. In all the records of an astronomical character that have come down to us we find allusions to this famous group of northern stars. It is unquestionably the most ancient of all the constellations, and universally known as “the Bear.”

On the banks of the Euphrates thousands of years ago it was so designated, and the Iroquois Indians of North America called this star group “Okouari,” their name for “bear.” The Algonquin Indians called the constellation “the Bear and the Hunters,” and as they were evidently sensible of the incongruity of attributing a conspicuously long tail to an animal that had none, they consequently regarded the three stars in the tail of the Bear as three hunters pursuing the beast.

The Finns called Ursa Major “Otawa,” a title resembling the “Okouari” of the Iroquois, and it is inferred that they regarded this constellation as representing a Bear.

Thus in remote parts of the earth, in the far north, from the valley of the Euphrates to the region of the Great Lakes of North America, we find the same stars likened to an identical animal, “the relic of some primeval association of ideas long since extinct.”

The arrangement of the stars in Ursa Major in no way suggests a bear, or any other animal, and even if one nation should so picture it, there is no reason why the same imaginative creation should be universally identical.

Aristotle held that the name was derived from the fact that of all known animals the bear was thought to be the only one that dared to venture into the frozen regions of the north and tempt the solitude and cold.

Prof. Max Muller thinks that the name of the Great Bear is the result of a mistake as to the meaning of words. The Sanscrit name “Riksha” signifies both “bear” and “star that is bright.” The seven bright stars in this constellation form such a striking group that they might well merit the title “Riksha” in its latter sense. It has been suggested that the constellation was called “the Bear” as a pun on this word “Riksha.” Later on, this word was confounded with the word, “Rishi,” and so connected with the Seven Sages or Poets of India, the Seven Wise Men of Greece, the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus, and the Seven Champions of Christendom. The ancient Hindus believed that the seven bright stars of Ursa Major represented the seven principal rich men or holy persons who were supposed to live beyond Saturn, but the inhabitants of northern Asia, the Phœnicians, Persians, and others, all saw in these bright stars of the north the likeness of a great bear.

On the famous zodiac of Denderah on the Nile, is pictured the leg of an animal. This is identified by the authorities with a constellation called “the Thigh,” which beyond question is the figure now known to us as Ursa Major. The Egyptians called this constellation “the Hippopotamus,” “the Dog of Set,” or “of Typhon,” and in latter days “the Car of Osiris.”

The Greeks called this star group “Aρχτσς μεγ λη, whence we get our word “arctic.”

λη, whence we get our word “arctic.”

It has been suggested that the word “Ursa” is derived from “Versus,” because the constellation is seen to turn about the Pole.

Homer mentions the Bear as keeping watch from his arctic den upon the hunter Orion for fear of a sudden attack. He regarded the constellation as only composed of the seven stars which form the familiar figure of the Dipper, and in his description of the shield of Achilles, he writes, after mentioning other stars, of “the Bear surnamed the Chariot.” Homer’s twice repeated assertion that “the constellation of the Bear alone never sinks into the ocean” merely allows us to infer that in his age the Greek sphere did not yet comprise the constellations Draco, Cepheus, Cassiopeia, and Ursa Minor, which likewise never set.

Even in Homer’s day Ursa Major was known as “the Wain,” the name by which it is known in England today. This title was originally “Charlemagne’s Wain,” from the Scandinavian Karlsvagn, the Carle’s Wain. Another title was Arthur’s Wain, a name, says Smyth, derived from the Welsh “Arth,” a bear. Smyth finds in the circling of this constellation about the Pole the possible origin of King Arthur’s famous Round Table.

In all probability it is this group of stars and not Arcturus which is referred to in Job’s question:

Canst thou guide Arcturus with his sons ?

In the Revised Version it reads:

Canst thou guide the Bear with her train ?

The word from which Arcturus was derived was “ ‘Ayish” or “ ‘Ash,” a word that does not differ importantly from the word “na’sh,” the Hebrew word for assembly, the Arabic “bier,” a title among the Arabs for the four stars forming the Dipper, from remote antiquity.

The three stars which form the tail of the Bear were called by the Arabs “Ben t-na’sh,” the “daughters of the Bier.” “Regarding Arcturus as referring to the Bear,” says Maunder, “we have in both passages of Job which mention Arcturus, Orion, the Pleiades, and the Chambers of the South the four quarters of the heavens marked out as being under the dominion of the Lord. In the ninth chapter they are given in this order: The Bear which is in the north, Orion in its acronical rising with the sun setting in the west, the Pleiades in their heliacal rising with the sun rising in the east, and the Chambers of the South.” In the Breeches Bible the note on the word “Arcturus” reads: “The North star with those that are about him.”

t-na’sh,” the “daughters of the Bier.” “Regarding Arcturus as referring to the Bear,” says Maunder, “we have in both passages of Job which mention Arcturus, Orion, the Pleiades, and the Chambers of the South the four quarters of the heavens marked out as being under the dominion of the Lord. In the ninth chapter they are given in this order: The Bear which is in the north, Orion in its acronical rising with the sun setting in the west, the Pleiades in their heliacal rising with the sun rising in the east, and the Chambers of the South.” In the Breeches Bible the note on the word “Arcturus” reads: “The North star with those that are about him.”

It seems more consistent with the stellar arrangement to regard the four stars forming the bowl of the Dipper as representing a bear, and the three stars in the handle of the Dipper as representing the cubs following in her steps, “her train,” than to regard the constellation as a bear with a long tail.

The Arabs also had a consistent figure in the Bier with three mourners following. This title “the Bier” is so similar to the almost universal appellation “the Bear,” that we might almost suppose that the latter title was a confused rendering of the former.

In some time antedating history, nomads of the east familiar with this constellation of “the Bier” may have reached North America and there conveyed their conception of this star group to the Indians, who translated the idea into terms familiar to their lives. The bier was distinctly an object familiar in the Orient, and foreign to the western savage, whereas the bear was foreign to the far east and familiar to the western Indian, whose life was bound up in the hunt. It therefore seems natural that in the east we should find the bier followed by the mourners represented by these prominent stars of the northern sky, and among the Indians we should see this same star group likened to a bear pursued by hunters.

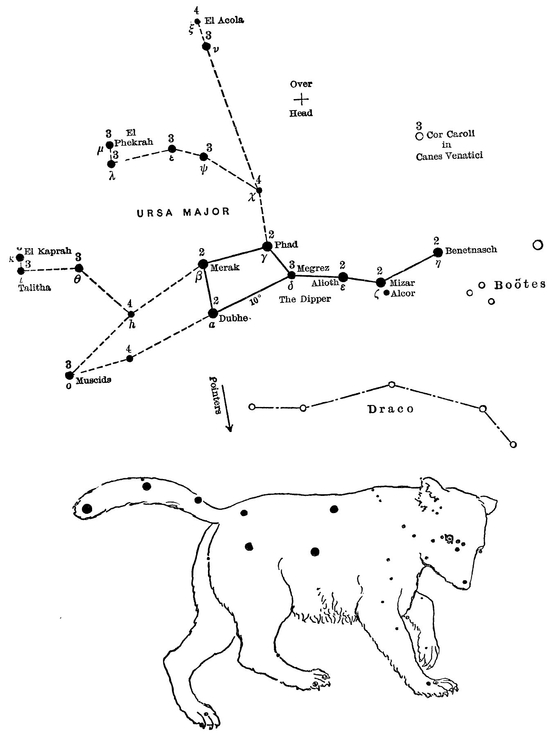

Proctor is of the opinion that originally this was the only Bear constellation, and that it was a much larger figure than at present. Modern astronomers, finding a great vacant space where formerly the Bear’s large frame extended, formed there the new constellation “Canes Venatici,” the Hunting Dogs. No one can recognise a bear in the present figure of the constellation, but Proctor says that one who looks attentively at the part of the skies occupied by the constellation will recognise, if they are imaginative, a monstrous bear with the proper small head of creatures of the bear family, and with exceedingly well developed plantigrade feet.

The feet of the Bear are marked by three pairs of stars strikingly arranged, and Maunder agrees with Proctor in considering that these conspicuous stars suggested the feet of a great plantigrade animal. Of course the figure cannot at all times be recognised with equal facility, but before midnight during the last four or five months in the year the Bear is seen, either upright in the heavens, or as if descending a slope, and favourably situated for observing.

Stories of the descent of tribes from animals are widespread among the ancient annals of the race, the Akkadians, Australians, red Indians, Bushmen, Bedouins, and other wild races believing that they sprang from such a source. The Akkadians considered that they were descended from a bear, and hence transferred the creature in fancy to the stars. They were known among the ancients as “the Bear Folk.”

The growth of the Bear from his original seven stars was obviously prompted by a desire to make the animal correspond in size to the long tail which appeared in the original figure. The stars adapted themselves fairly well for the purpose, and there was no other constellation in the way.

The Tower of Babel, the most ancient of temples, was called “the Temple of the Seven Lights,” or “the Celestial Earth.” It embodied the astronomical kingdoms of antiquity. The seven lights were, it has been thought, the seven stars of the Great Dipper.

Mythology links together in one story the constellations of the Greater and Lesser Bears:

The legend relates that Callisto, a nymph, the beautiful daughter of Lycaon, King of Arcadia, incurred the jealous wrath of Juno. Jupiter, fearing that Callisto would suffer injury at Juno’s hands, transformed her into a bear. Juno on perceiving this induced Diana to kill the bear in the chase, but Jupiter placed his favourite out of harm’s way in the starry skies. Callisto’s son Areas afterwards became the constellation of Ursa Minor.

Addison, in his translation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, thus writes that Jove—snatched them through the air

In whirlwinds up to heaven and fix’d them there;

Where the new constellations nightly rise,

And add a lustre to the northern skies.

Juno, it is said, indignant at the honour thus shown the objects of her hatred, persuaded Tethys and Oceanus to forbid the Bears to descend like the other stars into the sea.

Homer in the following lines thus alludes to the perpetual punishment meted out to Callisto and Areas:

Arctos, sole star that never bathes in th’ ocean wave.

Bryant also writes in like vein:

The Bear, that sees star setting after star

In the blue brine, descends not to the deep.

The Bear now sets except in high latitudes, but in Homer’s day and long before, his stars did not sink below the horizon or lave the seas.

Lowell in “Prometheus” thus refers to the Bear:

One after one the stars have risen and set,

Sparkling upon the hoar frost of my chain

The Bear that prowled all night about the fold

Of the North Star hath shrunk into his den,

Scared by the blithesome footsteps of the dawn.

Ovid gives a slightly different version of the legend. According to him, Juno changed Callisto into a bear, and when Arcas was out hunting and unwittingly about to slay his mother in the guise of a bear, Jupiter placed the bear and the hunter among the stars.

According to another legend this constellation represented a Princess, transformed into a bear on account of her pride in rejecting all suitors. For this her skin was nailed to the sky as a warning to other proud maidens.

Aratos made the two Bears the Cretan nurses of the infant Jupiter, afterwards raised to heaven for their devotion to their charge. Lewis disregards this legend on the ground that Crete never contained any bears.

A modern Grecian legend relates that originally the sky was supposed to be made of glass which touched the earth on both sides. It was soft and thin, and some one nailed a bearskin upon it. The nails became stars, and the tail of the Bear is represented by three bright stars, which are also known as “the handle of the Great Dipper.”

The Iroquois Indians had a legend concerning this constellation which was as follows:

“A party of hunters pursuing a bear were attacked by three monster stone giants, who destroyed all but three of them. These, together with the bear, were carried up to the sky by invisible hands. The bear is still being pursued by the three hunters. The first carries a bow, the second a kettle to cook him in (this is represented by the little star Alcor), and the third carries sticks with which to light a fire when the bear is slain. In the autumn the first hunter hits the bear, and the bloodstains from the wounded bear tinge the autumn foliage.” This legend is similar to that of the Housatonic Indians, who roamed through the valley from Pittsfield to Great Barrington. They believed that the chase of the bear lasted from spring until autumn, when the animal was wounded, and its blood was seen on the crimson foliage of the forest.

Stansbury Hagar, in an interesting monograph on The Celestial Bear, relates much of interest in this connection, which the writer takes the liberty of quoting in part. In some particulars the legends he recites coincide with the Indian legends previously referred to, but there are many interesting details in addition which reveal the active imagination of the American Indians in its relation to these famous stars.

“It is probable that in no part of the world has the observation of the stars exerted a greater influence over religion and mythology than amongst the native civilised people of Central and South America. Throughout their mythology the most beautiful legends are those associated with the heavens, and the two stellar groups which seem to have played decidedly the most conspicuous parts in these legends are the Pleiades and the Great Bear.

“These star groups figured prominently in the legends of the North American Indians also, and we can easily imagine the astonishment of the early missionaries when they pointed out the stars of the Great Bear to the Algonquins and received the reply: ‘But they are our Bear stars too.’

“This constellation, famous in the mythology of the Orient, seems to have been called ‘the Bear’ over nearly the whole of our continent, when the first Europeans of whom we have knowledge arrived.

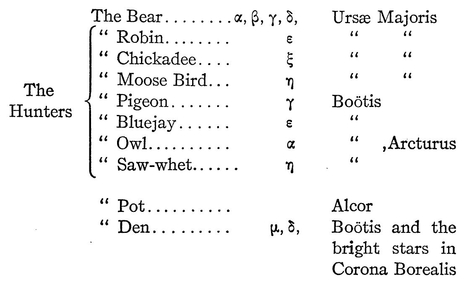

“It was known as far north as Point Barrow, as far east as Nova Scotia, as far west as the Pacific coast, and as far south as the Pueblos. The best-known legend concerning this star group is common to’ the tribes of the Algonquin and Iroquois Indians, and beside Ursa Major it embraces the neighbouring constellations Boötes and Corona Borealis. It is in the form of a drama with the following Dramatis Personæ:

The Bear is thus represented by the four stars in the bowl of the Dipper, and behind are seven hunters pursuing her. Here again we find the number seven associated with this constellation.

“The first hunter was called ‘the Robin’ because that star has a reddish tinge, the second ‘the Chickadee’ because its star is smaller than the others, the fifth hunter the Bluejay because its star is blue. Arcturus becomes the Owl because of its large size, and the star of the seventh hunter, the Saw-whet, because its reddish hue suggests the brilliant feathers which mark the head of that bird.

“Close beside the second hunter is a little star (Alcor), which represents the Pot which he is carrying to cook the bear meat in. Just above the hunters is a group of smaller stars which represent the Bear’s den.

“Late in the spring the Bear, waking from her long winter sleep, leaves her rocky hillside den and descends to the ground in search of food. Instantly the sharp-eyed Chickadee perceives her, and being too small to undertake the pursuit alone, calls the other hunters to his aid. Together the seven start after the Bear, the Chickadee with the Pot being placed between two of the larger birds so that he may not lose his way. All the hunters are hungry and pursue eagerly, but throughout the summer the Bear flees across the northern horizon and the pursuit continues. In the autumn one by one the hunters in the rear begin to lose their trail. First of all the Owl, heavier and clumsier of wing than the other birds, disappears from the chase, next the Bluejay and Pigeon also lose the trail and drop out. This leaves only the Robin, Chickadee, and Moose Bird. At last about mid-autumn they succeed in overtaking their prey. The Bear at bay rears up and prepares to defend herself, but the Robin pierces her with an arrow and she falls over on her back. The Robin, in haste to feed upon the Bear, leaps upon his victim and becomes covered with blood. Flying to a maple tree near at hand in the land of the sky, he tries to shake off the blood, and succeeds in getting it all off save a spot upon his breast. ‘That spot,’ says the garrulous Chickadee, ‘you will carry as long as your name is Robin.’ The blood which the Robin shook off spattered far and wide over the forests of earth below, and hence we see each autumn the blood-red tints on the foliage. The Chickadee now arrives on the scene and with the Robin cuts up the Bear, builds a fire, and cooks the meat. The Moose Bird now appears; he knew the others would catch the Bear and prepare the meat, and wanted only to be on time to share it, so whenever a bear or a moose or other animal is killed to-day you will see him appear to demand his share. That is why he is called ‘He-who-comes-in-at-the-last-moment.’

“Through the winter the Bear’s skeleton lies upon its back in the sky, but her life spirit has entered into another Bear who also lies upon her back in the den, invisible, sleeping the winter sleep. When the spring comes around, the Bear will again issue forth from the den, to be again pursued by the hunters, and so the drama keeps on eternally.”

With the Zunis, Ursa Major was important as marking the seasons. They say that when winter comes the Bear lazily sleeps, no longer guarding the westland from the cold of the ice gods and the white down of their mighty breathing, but, when the Bear, awakening, growls in the springtime and the answering thunder mutters, the strength of the ice gods being shaken, the reign of summer begins again.

The Chinese say that in spring the tail of the Bear (the Micmac three hunters) points east, in summer south, in autumn west, in winter north,—a correct statement for the forepart of the evening.

The Ojibway Indians have a legend which relates that a southern star came to earth in the form of a beautiful maiden, bringing the water lilies. Her brethren can be seen far off in the north hunting the bear, whilst her sisters watch her in the east and west.

The Onondaga Indians knew the stars representing the bear’s den, which is formed by the stars in the constellation Corona Borealis. The Cherokees also know the legend of the celestial bear hunt, and say that after the three hunters have killed the bear in the fall they lose the trail and circle helplessly around till spring. They assert that the honey dew, which is noticeable in the autumn, comes from the bear’s fat which they are trying out over a fire.

The Blackfeet Indians have known these seven stars of the Dipper as seven boys, all of whom had been killed by their sister save the youngest (the star Dubhe), who killed her in turn.

The Point Barrow Eskimos recognised the stars of the Bear with the seven hunters around him, and the Zunis call the group “the Great White Bear of the seven stars.” These stars seem to have played an important part in Pueblo mythology.

The Thlinkeets of the Pacific Coast regarded the stars of Ursa Major as representing a Bear. They thought that the Bear was so-called because its stars act so like a bear, slowly circling about; then too there is a den represented by a group of stars, and no other animal save the bear has a den of that shape. The Micmac Indians noticed these similarities between the position of these stars and the habits of the bear, and they were the source of many of the Indian legends.

According to a Basque legend, a farmer had two of his oxen stolen by two thieves. He sent his servant in pursuit of them, and as he did not return he despatched his housekeeper and dog, and finally as no one returned he went after the thieves himself. Because he lost his temper in his search for the oxen he is condemned to continue it for ever, and thus we find them all represented in the seven stars of the Dipper. The first two stars (the Pointers) represent the two oxen, then follow the two thieves, the servant, the housekeeper with the little dog (the star Alcor), and lastly the farmer himself.

The Basques are also said to believe that when the Bear is above the Pole the season is hot and dry, when below it the season is wet.

Another legend respecting these famous stars relates that they represent a peasant’s waggon. The peasant, so the story runs, met our Saviour near the shores of Galilee, and gave him a ride in his waggon. He was rewarded for his kindness by a place in the heavens, whither he and his conveyance were transported.

To the Eskimos, Ursa Major represented four men carrying a sick or dead man. The idea of a bier associated with the constellation in the east seems to be embodied in this notion of the Eskimos. The Eskimos also recognised the Great Dipper as a herd of reindeer.

Ursa Major was used long before the invention of the mariner’s compass to guide the paths of ships at night, as Manilius informs us:

Seven equal stars adorn the greater Bear

And teach the Grecian sailors how to steer.

These stars were equally valuable as guides to those who travelled long distances through unknown lands. According to Diodorus Siculus, travellers in the sandy plains of Arabia were accustomed to direct their course by the Bears.

The Greeks made the Great Bear their guide in navigation, whereas the Phœnicians steered by the Lesser Bear.

The Greeks called the Great Bear χαλλ στη from the Phœnician “kalitsah,” meaning safety, as the observation of these stars helped to a safe voyage.

στη from the Phœnician “kalitsah,” meaning safety, as the observation of these stars helped to a safe voyage.

Aratos wrote:

By it on the deep

Achaians gather where to sail their ships.

In the Odyssey, the sailing directions to Ulysses bid him keep the Bear always on the left, that is, to steer due east.

Aratos says that the Sidonians steer by the Little Bear, and that it is preferable to the Great Bear as it is situated nearer the Pole.

In this connection Apollonius mentions Ursa Major, which was often called “Helice” by the Greeks:

Night on the earth pour’d darkness on the sea,

The watchful sailor to Orion’s star

And Helice turned heedful.

Among the Chinese, the Great Bear was known as a bushel or measure of corn, the tail being the handle of the measure. Here, as in the case of the titles “Wain,” “Plough,” and “Bier,” we have a plain case of imitative name giving.

The ancients associated the idea of dancing with Ursa Major and the other circumpolar constellations, and they not infrequently mention “the dances of the stars.” The two Bears were imagined as reeling around the Pole like a pair of waltzers.

Onward the kindred bears with footsteps rude

Dance ’round the pole, pursuing and pursued.

This comparison is drawn from the circular dances of the Greeks, and alludes principally to the motion of the stars in the immediate vicinity of the Pole.

... round and round the frozen pole

Glideth the lean white Bear.

Buchanan.

There is some little interest in Ursa Major on account of the possibility of its being used as a kind of celestial timekeeper. The northern sky is in reality a great clock dial, over which hands wrought of stars trace their way unceasingly. Moreover, it is a timepiece that is absolutely accurate, and which requires no winding or repairing. A line drawn through α and Ursæ Majoris, or “the Pointers” as these stars are called, passes almost exactly through the pole of the heavens. Now this line revolves with the constellation once in twenty-four hours. On March 21st at 10.55 P.M., the superior passage takes place; a like passage, but invisible, occurs on Sept. 22d at 10.55 A.M. Knowing the day of the month, the time may be derived by observing what angle the line joining these stars makes with the vertical. In Shakespeare’s King Henry IV. the Carrier exclaims:

Heigho: an’t be not four by the day I’ll be hanged

Charles’s Wain is over the new chimney.

And Falstaff says:

We that take purses go by the moon and the seven stars.

Poe in one of his poems writes:

And star dials pointed to morn.

Tennyson wrote :

We danced about the May-pole and in the hazel copse

Till Charles’s Wain came out above the tall white chimney tops.

And again in The Princess:

I paced the terrace till the Bear had wheel’d

Thro’ a great arc his seven slow suns.

Spenser also alludes to this celestial timepiece in the Faerie Queene:

By this the northern wagoner had set

His sevenfold time behind the steadfast starre.

In a Blackfoot Indian myth we read: “The seven Persons [the Dipper] slowly swung around and pointed downward. It was the middle of the night.” This shows that the Indians were accustomed to mark time at night by the position of the circumpolar stars.

Allen tells us that the Bears have been frequently found on the old signboards of English inns, and in a more important way are emblazoned on the shields of the cities of Antwerp and Gröningen, in the Netherlands.

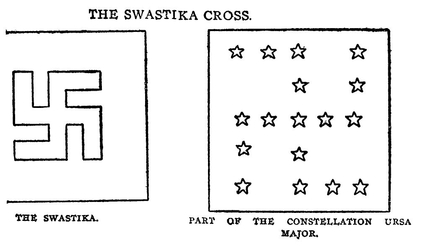

The well-known talisman of good luck, the Swastika Cross, is considered the oldest cross and symbol in the world. It is said to have been familiar to primitive man as a part of the constellation of Ursa Major, the portion popularly known as “the Dipper.” The stars that trace the cross form the figure of a Dipper whichever way the cross is turned.

The Arabs imagined Ursa Major and Ursa Minor to be a gazelle and its young, and the three conspicuous pairs of stars in the feet of the Great Bear represented to them the footprints of several gazelles, which, according to a legend, sprang from that spot when the Lion lashed the sky with his tail. The Lion, so the story runs, pursued the gazelles, and some of them jumped for safety into the Great Pond which is formed by a group of stars in Ursa Major.

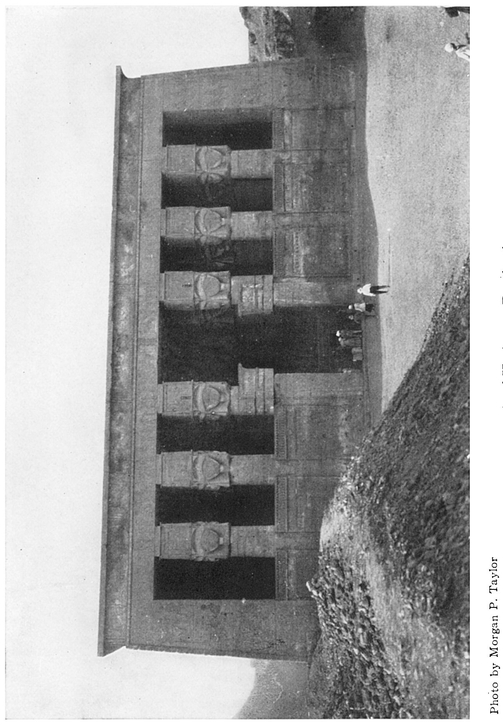

α Ursæ Majoris is named “Dubhe,” meaning the “Bear” or “She Bear.” The title is derived from an Arab phrase meaning the back of the Bear. Lockyer identifies this star with the Egyptian “ k,” meaning the “Eye,” the prominent one of the constellation. This star was utilised in the alignment of the walls of the temple of Hathor at Denderah, and was the orientation point of that structure before 5000 B.C.

k,” meaning the “Eye,” the prominent one of the constellation. This star was utilised in the alignment of the walls of the temple of Hathor at Denderah, and was the orientation point of that structure before 5000 B.C.

The Chinese called this star “Heaven’s Pivot.” It is located five degrees from β and ten degrees from δ Ursæ Majoris, and about twenty-eight degrees from Polaris, the Pole Star. These measures are useful to bear in mind in estimating celestial distances.

α and β Ursæ Majoris have been called “the Pointers,” “the Keepers,” and “the Two Stars.” Dubhe is the only star in the Dipper that is of the solar type. It is approaching our system at the rate of twelve miles a second, and has an 11th magnitude companion discovered by Burnham in 1889.

β Ursæ Majoris was known to the Arabs as “Merak,” meaning the “loin.” The Chinese called it “an armillary sphere,” and the Hindus regarded it as “Pulaha,” one of the Rishis. It is of the Sirian type, a spectroscopic double, and is approaching the earth at the rate of eighteen miles a second.

γ Ursæ Majoris, also called “Phecda” or “Phad,” meaning the “Thigh,” is approaching our system at the rate of sixteen miles a second.

δ is known as “Megrez,” meaning the “Root of the Tail.” It is the faintest of the seven stars in the Dipper. The position of Megrez and the star Caph, β Cassiopeiæ, is peculiar. These stars are both in the equinoctial colure, one of the great circles passing through the poles, and are almost exactly opposite each other, and equally distant from the Pole. Megrez is on the meridian at 9 P.M., May 10th.

These four stars forming the bowl of the Dipper were called by the Arabs “the coach of the children of the litter.” They form the hind quarters of the Bear, the frame of the Bier, the Plough, and the Wain.

ε Ursæ Majoris bears the name “Alioth.” According to Gore, this is a corruption of an Arabic word meaning “the Gulf.” Alioth is approaching us at the rate of nineteen miles a second, and very nearly marks the place of the radiant point of the Ursid meteor shower of Nov. 30th. It is a spectroscopic binary.

The Temple of IIathor at Denderah

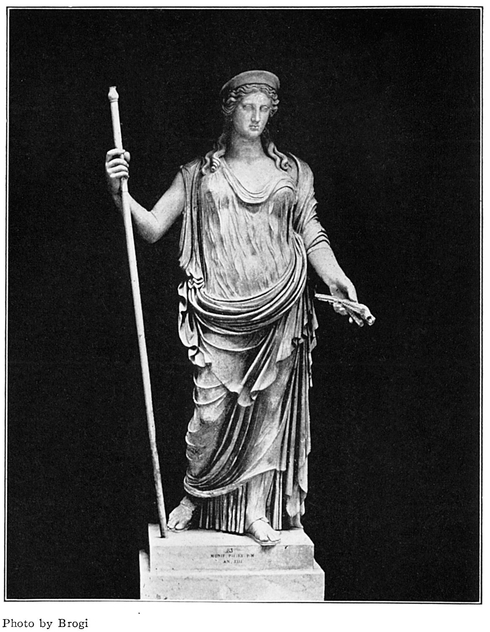

Ceres In the Vatican, Rome

ζ, also called “Mizar,” is the most interesting of all the stars of the Dipper. Maunder says that in every way it is the first of double stars. The fourth magnitude star Alcor forms with it a naked eye double, and it has a closer companion visible in the telescope. Mizar was the first double star discovered telescopically, having made the discovery at Bologna in 1650. It was also the first double star to be photographed, and the first star discovered to be double by the spectroscope. In India, Mizar was regarded as one of the seven sages. It is approaching our system at the rate of nineteen miles a second.

η Ursæ Majoris, the last of these seven famous stars, was called “Benatnasch,” meaning the “Governor of the Daughters of the Bier,” i. e., the chief of the mourners. It was also known as “Alcaid.” In China, this star was called “a Revolving Light,” and it marks the radiant point of the Ursid meteors of Nov. 10th. It is approaching the earth at the rate of sixteen miles a second.

Alcor is the name of the naked eye star close to Mizar. These two stars were called “the Horse and the Rider.” In North Germany the Rider is supposed to start on his journey before midnight, and to return twenty-four hours later, his waggon turning around with a great noise. The Arabs called this star “Suha,” meaning the “Forgotten,” “Lost,” or “Neglected One,” and they also called it “the Test,” an allusion to its visibility, as those who could see it were supposed to be keen of sight. The Arabs had the following proverb concerning this star:

I show him Suha and he shows me the moon.

The Arabs also called this star “Winter,” and “the Little Letter.”

The Greeks identified Alcor with the lost Pleiad Electra, who had wandered away from her companions and had been changed into a fox. A Latin title for the star was “the Little Starry Horseman.” In England it is called “Jack on the Middle Horse,” and in Germany it represented Hans the Waggoner rewarded for assisting our Saviour.

In the field with Mizar and Alcor is the so-called “Sidus Ludovicanium,” an eighth magnitude star of a bluish colour. This was first observed by Einmart of Nuremberg in 1691, and in 1723 another German, thinking he had discovered a planet, named it after his sovereign Ludwig V.

There are two noted stars in this constellation that remain to be mentioned. They are known as 1830 Groom-bridge, and Lalande 21,185. The former has been called “the Flying Star,” or “Runaway Star,” from the fact that its proper motion is swifter with one exception than any other star in the heavens. Its speed is so great that it would show a displacement equal to about one third of the apparent diameter of the moon in one hundred years. According to Argelander, its pace will carry it around the entire sphere in 185,000 years. Another authority asserts that in 6000 years it will reach the asterism known as Coma Berenices. Its estimated speed is two hundred miles a second, a pace that Newcomb claims is uncontrollable by the combined attractive power of the entire sidereal universe.

According to Prof. Young this star is 37.5 light years distant.

Lalande 21,185 is noted as being the nearest star to the earth of all the northern stars. Its magnitude is 7.4, and it is estimated to be 7.5 light years distant from the earth.

Five of the seven stars in the Dipper, those from β to ζ inclusive, are moving together in the sky all very nearly parallel to the line joining the first to the last. The remaining stars, α and η, are moving in almost an opposite direction, and both are receding at almost the same rate from a point in the sky not far from Vega. The accompanying diagram illustrates this movement. See p. 367.

Because of this drift, says Flammarion, they will form the figure of an exaggerated steamer chair 50,000 years hence, as they did a magnificent cross 50,000 years ago.

Since these stars are apparently getting farther apart, they must be approaching us, a fact which the spectroscope reveals. Their rate of speed varies from seven to ten miles a second.

These stars are all about the same distance from us, between ninety and one hundred light years, although one authority places the distance as high as 192 light years. According to Ludendorff all of the seven stars exceed our sun in brilliancy from thirty to one hundred and twenty times.

θ Ursæ Majoris is a double star, with six other stars near by in the throat, breast, and fore legs of the Bear. It describes a semicircle of stars which the Arabs called “the Throne of the Mourners.” This space was also known as “the Pond,” already referred to, into which the gazelles sprang when pursued by the Lion.

τ, was called “Talitha,” and in China τ and θ were known as “the High Dignitary.” Holden says that the companion of τ is supposed to be a planet.

λ, and μ were known respectively as Tania Borealis and Tania Australis. They mark the Bear’s left hind foot, and were the Arabs’ “Second Spring,” i.e., of the gazelle. In China they were “the Middle Dignitary.”

ν and ξ mark the right hind foot of the Bear. They were the Chinese “Lower Dignitary.” The latter star was the first binary of which the orbit was computed, says Allen. Savary in 1828 announced its period as sixty-one years, and this star has already made more than a complete revolution since its discovery.

o, the star that marks the nose of the Bear, was called “Muscida,” a word Allen claims was coined in the Middle Ages for the muzzle of an animal.

A few degrees from β is situated the so-called “Owl Nebula.” In Lord Rosse’s sketch of it there is a striking resemblance to a skull, there being two symmetrically placed holes in it, each of which contained a star before 1850. Since that date only one star is visible.

Twenty stars in this constellation have received individual names,—evidence enough, says Allen, of its antiquity and popularity. The following is a partial list of the titles conferred on this celebrated star group by the various peoples of the earth from remote antiquity.

Ursa Major was known:

In the Euphratean Star List—as the Lord of Heaven.

On the Assyrian Tablets—as the Long Chariot.

In Egypt—it was the Thigh, Bull’s Thigh, Fore Shank, Dog of Set, the Hippopotamus, and in later days the Car of Osiris.

The old Hindus called it the Seven Rishis or Wise Men.

In India—it was the Seven Bears, Seven Antelopes, Seven Bulls, Great Spotted Bull, and the abode of Seven Poets or Sages who entered the ark with Minos.

In China—it was the Ladle, the Bushel, the Government, the Divinity of the North, the Corn Measurer.

In Greece and Babylonia—the Chariot, the Plough, Helice, and Callisto.

The Christian Arabs knew the four stars in the bowl of the Dipper as the Bier or Great Coffin,—the three stars in the handle were the daughters of the Bier, Mary, Martha, and their maid.

In Rome—it was the Triones, Septentriones.

To the Hebrews—it was a Bier.

To the Syrians—it was a Wild Boar.

To the Druids—it was Arthur’s Chariot.

The Seven Stars have also been known as the Seven Wise Men of Greece, the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus, and the Seven Champions of Christendom; the Butcher’s Cleaver, the Big Dipper, the Brood Hen, and the Screw.

In the Middle Ages, Ursa Major was regarded by some as one of the bears sent by Elisha the prophet to devour the mocking boys, others thought it represented the Chariot of Elias.

Dr. Seiss regards it as symbolical of the heavenly sheepfold, and Schiller figured the Bear as the archangel Michael, and Peter’s Skiff.

In America—it was the Seven Little Indians, the Dipper.

In England—Charles’s Wain, the Plough.

In early England—Arthur’s Wain.

In Ireland—King Arthur’s Chariot.

In France—the Saucepan, Great Chariot, David’s Chariot.

In Italy—the Car of Boötes.

In Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Iceland, Scandinavia—Thor’s Waggon, Waggon of Odin.

In Lapland—the Reindeer.

The Eskimos’ name for the three stars in the tail of the Bear was the Many Reindeer.