UP TO THIS POINT WE’VE LOOKED AT A NUMBER of different means of grace. These are all practices that are more or less familiar to us. We can identify prayer easily enough, and we know what the Lord’s Supper looks like in the context of worship. Even if you hadn’t practiced some of the means of grace before reading this book, you were probably familiar with the concepts. Do all the means of grace take the form of particular practices, though? Or are there some means of grace that are more about our inner lives—the dispositions of our hearts?

Think for a moment about the difference between doing something where you are just going through the motions and doing something where you put your whole heart into that thing. The difference is huge. We can be talking about the very same activity either way, but your experience of that activity is going to be dramatically different depending on your level of attention and commitment. I played football growing up, and I remember how different a football practice could seem depending on whether I wanted to be there or not. If I was tired or hurt, the practice could be miserable. The heat seemed hotter and the drills took longer. But if I was really excited—if I knew that I was going to start in the game that week, or if the team was really coming together with a purpose—then practice could be downright fun. It was all about my inner attitude. When my heart was in it, the whole experience changed.

When it came to the means of grace, John Wesley knew that it was not enough just to talk about the spiritual practices themselves. It wouldn’t suffice just to talk about what we do. He also needed to talk about why we do what we do, and how we do what we do. His term for that is the “general means of grace” and it is the subject of this final chapter.

The general means of grace are related to our inward spiritual intention. When God speaks to our hearts, we find that our hearts are given power to yearn for God. We have to pay attention to this yearning, naturally, and we have to focus it toward God. But when we do, this inward spiritual focus then becomes a means of grace itself. It is a general means of grace because it affects our whole being. The remarkable thing we’ll find is that by affecting us generally, it enables us to experience each of the particular means of grace more powerfully.1

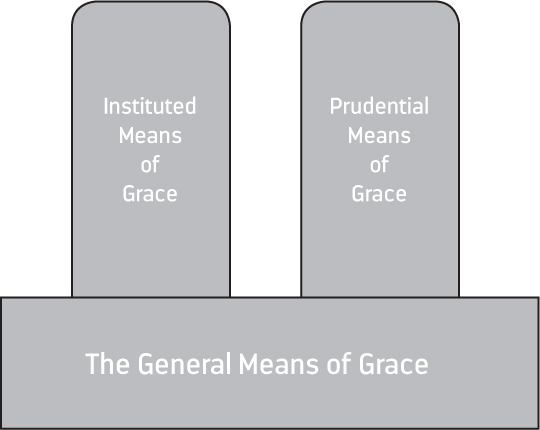

We can get a pretty good sense about what Wesley means by the general means of grace when we see how he compares this category with the other two we have seen so far—the instituted means of grace and the prudential means of grace. When he is explaining these different types of the means of grace to his preachers, Wesley first lays out the instituted means of grace and gives a list of them. Then he follows that by explaining what he means by the prudential means of grace. And at that point, he says something very interesting. “These means may be used without fruit,” Wesley says, and he’s talking about both the instituted and prudential means of grace! Essentially, he means that you can use them in such a mechanical way that they give you no spiritual benefit.

This makes sense when you think about it. I can mouth the words of a prayer without thinking much at all about what I am really saying. I can also sit through a sermon watching the preacher the whole time, all while my mind is on what I’m going to eat for lunch that day. I could walk forward to receive the Lord’s Supper, with my thoughts preoccupied with how angry I am at a coworker with whom I had an argument the week before. Or I could volunteer to serve meals at the local homeless shelter because it seems like a good thing to do, even though every minute I’m there I am focused judgmentally on how dirty and unkempt the residents of the shelter appear.

In each of these examples, the power that the means of grace might otherwise convey would be nullified by my absentmindedness or hardness of heart. With no inward sense of intention, God’s grace will never reach me. For grace to really have an impact on us, we must be open to it. And for the means God has provided to act as channels for that grace, we have to have a desire to meet God in those means! That is Wesley’s point by saying that we can use all of the instituted and prudential means in a way that makes them useless.

Wesley goes on, though, to explain that there are some means which cannot be used without fruit. They are always going to be effective. And he gives a very interesting list of what he’s talking about: watching, denying ourselves, taking up our cross, and the exercise of the presence of God.2 The first three of those terms are all straight out of the Bible. The idea of watching (or keeping spiritually alert) shows up both in the prophets of the Old Testament and in Jesus’ teaching in the New Testament. Denying ourselves and taking up our cross also comes from Jesus, where he lists these two things as necessary for anyone who would seek to follow him (Matt. 16:24). The exercise of the presence of God is not a direct quotation from Scripture, but it does appear to be closely related to the theme of God’s universal presence that appears in several of the psalms. Psalm 139 says,

Where shall I go from your Spirit?

Or where shall I flee from your presence?

If I ascend to heaven, you are there!

If I make my bed in Sheol, you are there! (vv. 7–8)

And Psalm 16 says,

You make known to me the path of life;

in your presence there is fullness of joy;

at your right hand are pleasures forevermore. (v. 11)

In both of these examples, the presence of God is depicted as being all around us and available if we will but open the eyes of our heart to receive it. Watching, exercising the presence of God, and the rest are not particular practices in the sense of concrete activities so much as they are ways of being contemplative and intentional about the spiritual life.

Elsewhere, Wesley gives other lists of the general means of grace that are similar to the one I mentioned above. The items on each list are not always identical, but they do all have to do with our inward intentionality. In one listing, he adds universal obedience and keeping all the commandments to denying ourselves and taking up our cross. In another, he treats certain traits of the Beatitudes from the Sermon on the Mount as general means of grace: meekness, hungering and thirsting after righteousness, being merciful, and being pure in heart.

Hungering and thirsting after righteousness is a good example to use because the parallel between it and hungering and thirsting after food and drink is so plain. The Scripture passage comes from Matthew 5:6, which reads, “Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they shall be satisfied.” Hunger and thirst are “the strongest of all our bodily appetites,” Wesley explains. We never go a day without eating food and drinking water if we can help it. The craving for both will drive us to distraction if we go without them for just a few hours. “In like manner,” Wesley says, “this hunger in the soul, this thirst after the image of God, is the strongest of all our spiritual appetites when it is once awakened in the heart.”3 When we don’t try to numb our hunger for God with other things, we’ll have the inward desire to know and love God that will make us ready for his grace.

So the general means of grace are all about the inward dispositions of the heart. One of Wesley’s favored phrases to describe the true meaning of the Christian life is that it is expressed through “holiness of heart and life.” And get this: he never, ever reverses the order of those two. It is always holiness of heart and life and never holiness of life and heart. The reason is that he believes the inner nature of the heart will always end up ruling the outer actions of life. If you have a wicked heart or a lazy heart or a greedy heart, then eventually your life is going to be lived wickedly, slothfully, or avariciously. On the other hand, if you have a gentle heart, you will be a gentle person in your outward living. If you have a loving heart, then you will show love in all areas of your life. There’s a connection between this idea and how the general means of grace relate to all the other means of grace. Whether you want to call it being watchful, or being universally obedient, or exercising the presence of God, in the end all of those terms refer in some way to having the inward disposition to know and love God. Someone whose soul is accurately described by those terms is ready and willing to be transformed by Jesus Christ! And that results in the means of grace that look like practices of discipleship (the instituted and prudential) that will be spiritually effective when they are used. Because of this relationship between the various categories of the means of grace, I don’t think it is any exaggeration to say that the general means of grace are something like the foundation upon which all the other means of grace ought to be built. If we think about the general means of grace as the right disposition of our hearts, then using the general means of grace denotes doing all the other means of grace with the right spiritual attitude and intention.

The General Means of Grace serve as the foundation for all the other means of grace. When our hearts are attuned to God, we find that all those things we do in Christ’s name become spiritually transformative for us.

The biggest pitfall we can fall into when we are practicing most of the means of grace is that we can start to do them in an unthinking way. Earlier, I simply said that these discipleship practices wouldn’t be effective if we were just going through the motions when we were doing them. The consequences can actually be worse than that. And the reason is that it’s not in our nature to just tread water in our spiritual lives. We’re either sinking, or we’re swimming.

There’s a word to describe the danger we run into when we stop focusing on the inward disposition that we ought to have when we worship and pray and serve God. That word is “dissipation.” Dissipation is what happens when water evaporates out of a boiling pot. It just vanishes into the air and goes away. Our love for God can dissipate like that when we are not actively working to remain centered on God. In a sermon on that subject, Wesley explains how significant a danger this can be:

We are encompassed on all sides with persons and things that tend to draw us from our center. Indeed, every creature, if we are not continually on our guard, will draw us from our Creator. The whole visible world, all we see, hear, or touch, all the objects either of our senses or understanding, have a tendency to dissipate our thoughts from the invisible world, and to distract our minds from attending to him who is both the author and end of our being.4

His biblical example for this experience is the story of Jesus in the home of Mary and Martha in Luke 10:38–42. Mary recognizes how important it is to sit and listen to the Lord of life when she has the chance, so she sits at his feet and soaks up his teaching. Martha, on the other hand, is distracted by household chores. Her faith is dissipated, even as the Son of God himself sits in her living room. She has become “unhinged from her proper center,” as Wesley puts it elsewhere.5

Here is where the general means of grace become absolutely essential. They call us to stay focused on our proper center. To stay focused on God! We can be living outwardly good and dutiful lives—just as Martha was—but that doesn’t mean we are connected to God at all. A living relationship with Jesus Christ will sanctify us. It will transform us by his holy love. One way of thinking about these general means of grace is that they show us the difference between simply doing good deeds and truly receiving God’s gifts. If the right kind of inward intention is guiding our use of all the practices that make up the instituted and prudential means of grace, then we’ll experience them not as deeds but as gifts of God for our salvation.

In John Wesley’s thinking, there are two of the general means of grace that especially explain the importance of our inward attitude because he thought they served as easy-to-understand examples: Jesus’ twin commands to deny oneself and take up one’s cross. About self-denial, Wesley says that “to deny ourselves is to deny our own will where it does not fall in with the will of God, and that however pleasing it may be.”6 When he talks about “our own will,” the idea that he has in mind is that our own will is almost always going to lead us down the wrong path when left on its own. Because he often views the presence of sin as akin to a moral disease within us, Wesley tends to think of the effects of sin as constantly influencing toward thoughts, feelings, and actions that take us away from God. To deny ourselves would be to deny those basic worldly, sinful impulses that seem so attractive to us on their surface.

The flip side of the coin is Jesus’ command to take up one’s own cross. This has some real similarities to self-denial in the sense that cross-bearing also involves going against the natural tendencies we might have. Wesley writes, “A cross is anything contrary to our will, anything displeasing to our nature.” While this is a companion to self-denial, it actually raises the bar in terms of what it requires of us. “[T]aking up our cross goes a little farther than denying ourselves,” Wesley says, “it rises a little higher, and is a more difficult task to flesh and blood, it being easy to forego pleasure than to endure pain.”7 In other words, I can say “no” to something I would otherwise enjoy more easily than I can say “yes” to something that I positively don’t want to do.

Why are these two ideas so important to Wesley’s view of how our inward disposition is a general means of grace to us? Well, you can’t really deny yourself the things you most want, or take up things that are truly difficult for you, without thinking about exactly why you are putting yourself through that kind of unpleasant process. You have to be intentional about it. You have to be focused on what it means to deny yourself, or to take up your cross in some specific way. There is no way to deprive yourself of one thing (or burden yourself with another) without your inward intention being at the center of that whole process.

We’ve looked a little bit at how our cultural mind-set of consumerism makes real discipleship difficult. (That was particularly the case in the chapter on fasting, which in some ways has a particularly strong connection with the general means of grace.) The world around us wants to encourage us to indulge ourselves and avoid things that are difficult. This is just the opposite of Jesus’ commands to us! It may be that the general means of grace are needed now more than ever. We live lives of distraction: technology and media, in the form of smart phones and tablet computers and high-definition TVs, mean that we are rarely left alone with our thoughts. Contemplating ourselves and our relationship with God is so rare nowadays, in fact, that it is likely to make us fairly anxious when we first start to do it. I’m not sure there’s anything more important though. Ultimately, we will never build the holy habit of patterning our lives according to the means of grace if we do not focus on the need for mindful attention in all that we are doing. In some ways, the general means of grace must be focused upon for all the other means of grace to make a difference.

Everywhere I have served as a pastor, one of the most common requests I get from church members when it comes to pastoral care is about how to navigate the difficulties of personal relationships. Sometimes this has to do with spouses and other family members. Sometimes it has to do with coworkers and friends. Whenever a church member of mine has presented me with a difficult situation, I would always ask how he or she had responded (or intended to respond). It almost never fails that people will give me an answer related to their level of comfort with personal interaction. Some would say they were going to send a text or an e-mail. Others would say they intended to pick up the phone and make a call. Very few people said they wanted to seek out the person with whom they had a disagreement, sit down together, and talk.

Now ask yourself this question: Why wouldn’t the first reaction of people be to seek out those with whom things have become difficult so they could sit down together in person? I think it’s probably all wrapped up with fear, anxiety, and the desire to avoid confrontation. My pastoral counsel to such folks is always to think about how they naturally wanted to respond and then move at least one level up on the difficulty scale. If the impulse was to send a text message, they ought to make a phone call. And if they naturally thought of making a phone call, they should instead seek the person out face-to-face. The goal, of course, would be to always seek out a person face-to-face, but not everyone can do that right off the bat.

In a small way, this is about denying oneself and taking up one’s cross. Real relationships can be hard, but they are only built in a face-to-face manner. Doing the hard thing on the front end has positive consequences in the end. If you can think about your own discipleship like this, then you will begin to get a sense of how important the general means of grace are. We can use phrases that come from Jesus’ mouth, like “obey the commandments,” “deny yourself,” and “take up your cross.” Or, we can go with that little phrase that Wesley seemed to like so much: the exercise of the presence of God. The truth is that they are all pointing to the same idea, which is to be aware of God’s presence in your life and live your life in response to the grace he gives you in every moment.