PRINTS FROM COMPARTMENT FOUR

1876–2009

There were still buffalo-hunting Indians in those days, and sometimes, although rarely, the Nez Perces traded with the Sioux, whom they would rather fight

(Doc in Blurick’s prairie schooner detailing the way that some Sioux warriors wear bone gorgets as elaborate as accordions—not that Blurick cares because anyhow there’s plenty of Indians all over the country);

and there were more buffalo than even Doc could count

and Indians all over the country, if not quite so many as last year

and yellow grass, and thousands of wagons rolling through

(Doc calling the square dance while Baker played the violin);

soon the tall narrow pyramid of black girders would ascend into being, with the metal shed halfway up it, and the wheel shaft rotating on the stamping mill; never mind the Ice-Burg Drive-In and Tony’s Dutch Lunch; to get to that stage, we couldn’t wait on President Hayes! Yessir, no, ma’am; we cleaned out that country. A scout named Doc on a fine Kentucky thoroughbred promised to kill the first Indian he saw and shot a squaw sitting on a log, but what happened next to Blurick’s party I cannot say, nor do I even know where most of them settled, I hope in prime Oregon bottom land, so that the new Mrs. Blurick (so what if she ain’t yellowhaired?) could go out on a morning and fill two flour sacks full of blackberries—but Blurick might for commercial reasons have chosen or been chosen by some other Western venue far from Hood River, way away from Wallowa, never mind Portland or Pendleton: I mean someplace where the hot dirt streets of narrow-peaked white houses dead-ended in cliff-walls hot and grey with scree, and nothing but evergreens served for handholds, Blurick, date unknown, location unknown; for I had to leave his manuscript, it being now nearly closing hour at the Historical Society, where Tom stood ready to inspect and explain some Indian photographs I had served myself out of varnish-perfumed archive drawers straight from the Country of Dying Grass. Once upon a time there were so many buffalo along the Oregon Trail that you might see them stampede by for two hours. And Indians, too, I have read that there were quite a number of those.

Umatilla chief, Tom said. Not very good. Soft focus. Likely a dupe.

From the next yellow print, Indian eyes looked into me.— That starlike stamp on the reverse—W.A., you see—is Wesley Andrews. Wesley Andrews probably wasn’t even alive when this picture was taken. You can tell by the flattened tonal scale that values are not really where they need to be.

Oregon State Archives.

Umatilla Indian War Claims Register, 1877–78.

Locator 2/11/01/07, one volume,

General Sheridan gently smoking his cigar,

Captain Pollock, all spruced up, staring ahead with Sara and the children, pretending they have all been digging gold,

although that should have been filed under

Oregon State Archives.

Nez Perce Indian War, 1877.

No locator.

Wood and Nanny,

Wood and Theller’s squaw,

Wood and Sitka Khwan,

Wood and Mrs. Ehrgott,

silhouetted soldiers drawing up for inspection before General Howard’s Sibley tent, dawn-gazing straight ahead, as wilderness breathes on them an inch beyond the picket-rope;

Wilkinson in his Salvation Army uniform,

Colonel and Mrs. Perry seated on their porch at Fort Lapwai, he in his parade attire, she in a long dark skirt, trying to smile through that little black dotted veil she was always wearing

and then another print. Tom said: I recognize this. Bannock Indians. Azo paper is of course long discontinued now. You can still get it in grades one and four, but only if you order an enormous quantity. The fact that there are already three signatures stacked up means that it was old at the time it was printed. And here we have more exposures. This was already a thirty- or forty-year-old neg at the time.

Again! he said sadly. Another copy. Blacks piled up, whites blocked out. Now, this has been here a long time. Compartment Four refers to a filing that was used from the 1890s to the 1930s. Overland journeys, Todd, that’s fine. And this, I would be very skeptical. I would be doubtful that it’s a Bannock Indian village as labeled. And of course! Look at W. Andrews, Washington! He stole the picture from someone somehow, and he just captioned it Bannock because he thought it would sell.

When the Nez Perce War broke out, the Bannocks stayed loyally on our side,

sitting with their children in the golden grass, before the dark cones of their grass-skinned tipis, their heads hanging down, out of sun- or camera-shyness,

copyright Wesley Andrews,

and then helping us hunt down Chief Joseph:

in the next orange print, copyright registered in the name of that cunning time traveller Major Moorhouse, we see young braves in a line, safely mustered into the United States Army. One of General Howard’s white scouts, dawn-addicted young Redington, canters up to the recently abandoned Nez Perce camp at Squaw Lake and finds a poor helpless old squaw lying on ratty robes. She shuts her eyes as if expecting a bullet but not wanting to see it come. She seemed rather disappointed when instead of shooting her I refilled her water-bottle . . . from a couple of shots I heard ten minutes later as I followed the trail down the creek, one of our wild Bannock scouts acceded to her wishes . . .

Oregon State Archives.

Bannock Indian War, 1878.

No locator.

Indian chief, yes, I recognize this picture, said Tom. I have seen a receipt dated 1936, five cents on wholesale, Benjamin Markham, who was one of Andrews’s printers. The muddy shadows are not going to lend themselves to pictorial excellence.

Wagon train scout, called “Doc.” I can’t exactly place him, but he looks familiar. Now, if you put the loupe right down on his breast pocket, you can make out that medallion he’s wearing: DEMOCRATIC PARTY DIED OF TILDENOPATHY, 1876, IN THE 60TH YEAR OF ITS AGE. SHAMMY TILDEN, LET IT R.I.P. That dates this negative at right around the Centennial, so it should really be in Compartment Six. This Doc of yours, who looks like a mean bastard, was obviously a Hayes loyalist. Hayes or Tilden, what a choice!

Here came a postcard of an Indian at a county fair. The way the Indian looked at me, I felt the same sad thrill as that summer night when the locomotive whistled in Lewiston, Idaho. And the summer clouds of Oregon rushed along in the window like the ghosts of wagon trains.

Wallowa Lake, 1873. Copyright Major Moorhouse.

Nez Perces, 1877, location Wyoming.

Nez Perces, circa 1877, location Montana. They covered much ground that summer.

More dupes, said Tom. The flattened tonal scale is the dead giveaway here. There are no whites.

A platinotype presented us with a long slope of feather, then a bronze, faux-Roman Indian profile. That warrior knew the way to ford waterfalls. Tom said, still looking at the previous photograph: In the middle 1850s, an Army soldier had a camera and made salt prints. Let’s see, Grand conseil, Composé de dix Chefs nez-percé . . . And this so-called “platinotype” uses corn starch emulsion to make the matte look. But Moorhouse shouldn’t be in here. That’s vault material.

Oregon State Archives.

Nez Perce Indian War, 1877.

No locator.

From what must have been an albumen print—for its tones were red and its highlights had yellowed to the hue of late afternoon summer strawfields in Umatilla, so brightly pale a gold as to be almost green (and it was foxed and speckled as if with tiny towns in the dips of the grassy land)—Chief Joseph stared out, his mouth clenched, his forehead steeply sloping back into the feather and the wave of frozen hair, his eyes squinting narrowly as he held his calumet high and steady for the lens of Major Moorhouse in 1901. Can you believe that he still hoped to go home to the paleness of the summer morning sky over Wallowa? His throat was encircled in bead-strings, and more beads made necklace-waves upon his chest. A plaid blanket hung from his waist.

Dupe, said Tom. And this is Moorhouse’s famous picture of the Cayuse Twins. As you see, things keep getting worse and worse. Nez Perce warriors. Wesley Andrews photo number . . . That’s right. Now, pictures from The Dalles with the typewriter label stapled to the raw board, that’s the May Collection. Almost all the good pictures were stolen. The negs don’t exist.

Corpse of Nez Perce squaw, 1877, location Big Hole, Montana Territory, signed by Major Moorhouse. Nez Perce prisoners, 1877, Tongue River Cantonment, Montana Territory. Nez Perce prisoners, 1878, Indian Territory.

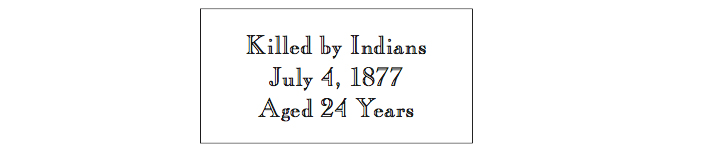

Nez Perces, 1877, location Idaho Territory. And right there in Idaho, tucked in among the high plains of orange grass, the grain silos like fat rockets of dull metal, the train tracks and farms, not far from that crazy old red barn with a cylindrical hay bale sticking out the window, stands William Foster’s grave:

which is to say, slain by Nez Perces.

From time to time Cayuse portraits get misfiled under Nez Perce, said Tom.

Oregon State Archives.

Cayuse Indian War, 1847–50.

Boxes 47–50. Locator 2/21/01/07, twenty-five cubic feet,

and proper reverence and regard for our patriotic memories

in the dry grass and sagebrush that chatters underfoot as my thoughts run toward Henry’s Lake, faster than Sherman’s telegraphed commands,

and for crowds of mounted hunters, with their lances, bows and rifles projecting upward like masts at various tilts,

and the triangular and quadrilateral zones of green, red, yellow and white on Crow Indian parfleche bags

and glory, lustre and

everything for Wallowa.

As for this image of Walla Walla warriors, said Tom, I’m skeptical. The caption’s been erased. In fact, I do recognize this image. This is a Nez Perce portrait, photographer unknown, stolen by Moorhouse:

Oregon State Archives.

Rogue River Indian War, 1855–56,

when Ben Wright made Chetcoe Jennie strip naked while he horsewhipped her through the mud-streets of Port Orford: Take it off, d——n you! now your drawers, you stinking redskinned bitch-whore fucking filthy pig, I’ll show you who you are, you savage, fucking stinking, fucking fucking GODd——d animal whore . . .—for which she arranged his murder, cut out his heart and ate a piece, and then the Rogue River War started,

No locator,

while O. O. Howard, not yet a general, takes part in Seminole removal down in Florida.

Oregon State Archives.

Modoc Indian War campaign journal, 1873.

Locator 2/21/07/04, one cubic foot,

including the records of Perry, Theller, Trimble, Pollock and Mason, who will all fight Chief Joseph.

Blurick was right; there were plenty of Indians all over the country. You might even say they were as plentiful as tobacco in Missouri.— Now the Nez Perces, Captain Travis explained to Blurick,

who just now, observing the stern fashion in which the widow’s ten-year-old daughter parts her hair, finds good breeding and prudence in her squinting appraisal of him in the moment when, striding soberly back from the creek with the cooking pail clean and full, she catches her smooth-armed cornhaired mother (who’s a considerably better looker than his foxy former landlady Mrs. Mack, not to mention the half-breed woman he used to meet behind the slaughter-house) slowing to cock a smile at him,

yes, him, Mr. Wittfield Blurick,

one time about thirty years back they come to us on the Powder River to warn about unfriendly Indians,

but what the shit do I care about Indians thirty years gone when the widow’s smiling at me?

And the daughter, O my LORD!

Anyhow, there’s still quartz of all colors all over the country,

but the color of her hair, O GOD:

sweet black loam at the mouth of Oro Fino creek! So them tents at Lewiston—

And thousand-dollar claims on Rhodes Creek—

Sure, dreamer, back when Honest Abe was President.

Well, Doc says—

Then why’s he still riding for Travis like some hired greaser?

How long before you found it out?

About Doc?

Who else?

and that quartz lode six miles below the Clearwater Forks—picked over going on sixteen years now, but still not entirely played out—

and Florence

(O, we always have a good time there!)

and LORD knows where else, up in the Bitter Root country, where we’ve cleaned up nearly all the Flatheads.

Doc’s just talking out his ass. Ain’t no gold in Wallowa.

Nobody can stop us, either. Joseph’ll do as he’s bid—

And Blurick—

Now Preacher’s paying her his addresses, GODd——n him for a tinhearted sonofabitch. And Brown’s not interested but Baker might be. But I’ll get her solid to myself. Bring her to my bosom. At least I hope I will. LORD, but this journey’s wearing on me now! I’ll sure never forget all this.

My uncle was there, and just as you say, he never forgot it. You sure you don’t want no tipple? I heard you call it Blackfoot rum. Well, it ain’t that; it’s the good stuff,

the cornhaired widow hastening into the tall grass with something wrapped up in her basket; well, there she goes, and I’d better act like one of the boys if I don’t want Travis against me because now he’s frowning with his hand on his hip, expressing his best General Grant, as if that could impress me:

Listen up, Blurick, you sly temperance dog: I smell yours on your breath! And you don’t share, except with Doc. I’ll stand you a taste and you stand me one, all right? All right. Now, the bad Indians up there, they call ’em Walla Wallas. And when Doctor Whitman had to hold the Walla Walla chief at gunpoint to keep the rest of those devils from murdering everybody, well, that night went on longer than ten GODd——d years, but finally our Nez Perces come riding in and turned the tables! I have to say they was all right, especially for Indians. Looking-Glass’s Daddy was there, and so were Joseph’s and White Bird’s. All big chiefs. Now their sons got the same names. Crazy about blue beads even to-day, so that’s what we give ’em. And gold in their country, maybe even as much as in the Black Hills. Time for them to stop roaming and settle down. Not many at all around the Hood River where you’re fixin’ to go, but when we roll into Grande Ronde you’re bound to see some, mixing in with them Dreamers and river renegades. Nez Perces means pierced noses, but most of ’em, I would say, they leave their noses alone. When you see Nez Perces riding toward you, you can more or less trust ’em, so you don’t want to shoot. I already told Doc, he shoots a Nez Perce and I’ll knock his teeth out. But what I myself would do in Hood River, Mr. Blurick . . .

I showed Tom a reddish-brown scene from a Pendleton Roundup, a horseback rider horned like a Viking chieftain, a line of Indians with beaver-fur mantles and feathers in their hands.

This picture, I recognize the backdrop, said Tom. This is off the original neg. You can see the emulsion flaking off, all the troubles of being a first-class neg. Here’s where you want to be,

near Pendleton,

the lovely low golden-grassed hills and

gold mines somewhere (but they’ve shut Florence and Oro Fino down almost before Blurick got convinced)

the sky as cloudless as new bluing on a Remington’s rolling block (real fine weather in this section) and then, far away, a pale stripe of low grass bearing zones of blue-grey trees where even last year we could do pretty well cutting down poles from Indian scaffold burials for our campfires;

then down into the valley of golden grass

(my heart is good)

where three yellow locomotives and many red container cars creep over the Umatilla River and into Pendleton,

an amputated string of grainers by the white cylindrical towers of the Pendleton Flour Mill,

creosote fumes rising up from the hot black railroad ballast, the single track running black and true along the base of a wide round hill of yellowish-white grass whose mostly deciduous trees, olive-green and dark reddish-green, shade the steep-roofed antique houses, tall and narrow, which look down across the gulley toward the grassy dirt-hills of the north,

then inside the Pendleton Woolen Mills the following testimonial, illustrated with a portrait ostensibly taken by the camera of Major Moorhouse:

Now there’s a valley I heard tell of, said Doc; they call it Wallowa. And I ain’t never been there, Mr. Blurick, but it’s Heaven, is what they do say. They opened it up to settlement just lately. See, looky down here on this map. Due east of the southeast corner of Township Number One, then right here where the Wallowa flows into the Grande Ronde. It’s only Nez Perces up that way. Tame Indians. The cavalry’ll round ’em up next summer, probably.

Multiple years of erasures, said Tom. What a mess this is, what a mess.

I always ask for my prints to be full fine crop, he remarked then. Sometimes you recognize little details that might be on the edge of the plate. That’s just what you need.

So I looked through the loupe, focusing on July 1876, and followed Blurick up to the Snake River,

and were I to more precisely delineate his insignificant trajectory in relation to those of the actual moving principals in our American story, I’d note that Colonel Miles, already called general, and advocate of flares, carrier pigeons and other modern methods of communication, is just now leading his column out of Fort Leavenworth in high hopes of liquidating Sitting Bull, subsequent to a stop at Fort Lincoln to re-condole with Mrs. Custer, who has not yet departed the ravening infancy of her widowhood;

while General Terry (the hero of everything) and Colonel Gibbon (the hero of Big Hole) respectively take the Fifth Cavalry and the Twenty-second Infantry;

so that General Sheridan, having demanded good news, sits smoking his cigar as tenderly as Rutherford B. Hayes handles Lemonade Lucy,

and Miles’s enemy, especially loathed for having made, unlike Miles, brigadier general, even attainted as he is

(captured by the Secceshes)

—I mean of course General Crook

(who unfortunately has the President’s ear)—

advances with the Fifth and the Fourth

(and Crook merely despises Miles for a blustering bumpkin, whereas he outright hates Terry)

and Chief Joseph, who is called Heinmot Tooyalakekt, flitters in and out of Wallowa, which is his home, but not his only home (each summer, we find him more in the way)

while General O. O. Howard, this Dream’s hero,

with whom Crook shares the habit of abstinence from spirituous drink and whom Crook scorns for what he, a cynical humorist, prefers to interpret as pious humbuggery

(for instance, standing before his opened Sibley tent, with a stick-cross high behind him, reading aloud from his Bible, with the soldiers keeping their slouch hats on until the prayer:

his face seemed longer and almost delicate when he was younger),

having commanded the Department of the Columbia for two years now, since the Modocs murdered Canby, stays in with Lizzie and the children at present, organizing Indian removal on paper:

The twenty-fifth will mark Harry’s seventh birthday already; he’s behaving very well; Lizzie wishes him to receive a new pair of shoes. He’s very fond of those lemon crackers which folks bring on the Oregon Trail; I wonder where I could find him some? Grace will doubtless bake some sweet or other to mark the occasion. Such an acomplished young woman she’s become; it brings a lump to my throat! But why can’t she keep her beaux? (Bessie will be delighted; she’ll probably believe the party’s for her.) And on his leave days Guy is always keen to keep up with Miles’s movements on my map. I must admit to entertaining the highest hopes of that son. Chauncey and John are the ones I hardly know, LORD help me—

and then through the loupe I followed the Columbia all the way to the emulsion’s flaking edge, up to Nespelem, where the hills are as soft as a moleskin shirt: