The siege of Nagashino castle and the battle of Nagashino which followed it make up one of the pivotal moments in the history of the samurai. Its military significance is considerable, because it demonstrated the power available through a skilful combination of arms, comparatively simple defensive measures and, above all, the use of firearms on a large and controlled scale. Other samurai leaders who later found themselves in a similar position would look for lessons that they could apply from the example of Nagashino.

The battle of Nagashino is but one among many conflicts of 16th century Japan. The period is known as the Sengoku-jidai (Warring States Period), a term borrowed from the Chinese dynastic histories. For the past five centuries Japan had been ruled by a succession of dynasties of Shoguns, the military dictators who ruled on behalf of an emperor who since 1185 had been reduced to the position of a figurehead. The Shogunates suffered many vicissitudes during those years. There had been attempts at imperial restoration, conflicts within ruling houses, and one episode of foreign invasion. However, until the mid-15th century the institution of the Shogun, which at that time was vested in successive generations of the Ashikaga family, still managed to control and govern the country.

The tragedy for the Ashikaga happened in 1467, when a civil war, known as the Onin War from the traditional ‘year’ in which it occurred, began to destroy Kyoto, the capital city of Japan. As the ashes settled the fighting spread further afield, setting in motion sporadic conflicts that were to last for 11 years. Some semblance of order was finally restored, but not before many samurai generals had realised that the Ashikaga Shogunate was gradually losing its power and authority, and that if the samurai wished to increase their land holdings by the use of force against their neighbours, then there was little likelihood of any intervention from the centre to stop them. Thus over the next 50 years Japan slowly split into a number of petty kingdoms, ruled by men who called themselves daimyô (great names). Some had held lands in their regions for centuries, and had increased their power by the readiness of neighbours to ally themselves to a powerful protector. Others seized power by murder, intrigue or invasion, and held on to that power by military might.

It would be a mistake to look upon the daimyô of the early 16th century as bandit leaders. In many cases their lands were well governed, and the men who worked in their rice fields, nearly all of whom were part-time soldiers, showed their overlords a degree of loyalty that the Ashikaga Shoguns would have envied. Such loyalty was expressed through willing and enthusiastic military service, carried out on the daimyô’s behalf when a call to arms was issued. It was said of the followers of one daimyô, the Chôsokabe of Shikoku Island, that these farmer-samurai were so ready to fight that they tilled the rice-paddies with their spears thrust into the ground at the edge of the field and their sandals tied to the shafts.

As the Sengoku-jidai wore on it was inevitable that smaller daimyô territories should be swallowed by bigger ones, until by about 1560 Japan consisted of a number of major power blocs, alternately in alliance or in conflict as the balance of power shifted from one lord to another. In the midst of it stood the Shogun, impotent in military terms but immensely powerful as a symbol. By ancient convention no one could become Shogun unless he possessed the appropriate lineage back to the original Minamoto family – an honour enjoyed by the Ashikaga. The secret to controlling Japan, therefore, was control of the Shogun.

In 1560 a decisive point was reached when a powerful daimyô called Imagawa Yoshimoto planned to march on Kyoto and set up his own puppet Shogunate. The first obstacle Imagawa had to overcome was a neighbour called Oda Nobunaga, whose much smaller territory was inconveniently situated between Imagawa and his goal. Full of confidence, the Imagawa army moved into Owari province, where they were unexpectedly and thoroughly defeated. Oda Nobunaga launched a surprise attack on them and succeeded in spite of odds of 12 to one against him. This victory, the battle of Okehazama, flung Oda Nobunaga into the big league of daimyô. His military prowess and his convenient location – not far from the capital – ensured alliances and support, not the least of which was a long-standing association with the ruler of neighbouring Mikawa province, Tokugawa Ieyasu, formerly a retainer of the Imagawa but freed from that obligation by the victory at Okehazama.

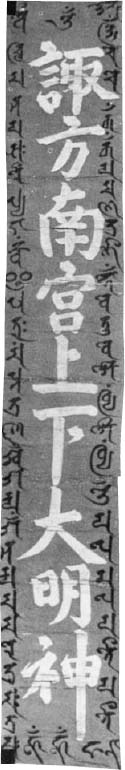

The two red banners of Suwa Myôjin, the deity of the area where the Takeda were based, treasured by the Takeda along with the ‘Sun Zi’ flag, and were carried into battle together with the blue flag. They bear invocations of the god in Japanese characters, while round the edge of the larger one is a religious incription in Sanskrit.

For the next 15 years Oda Nobunaga fought battles, made marriage alliances, arranged coups and built castles, until in 1568 he himself was able to enter Kyoto in triumph with Ashikaga Yoshiaki, whom he proclaimed Shogun. More battles and campaigns followed, among which there began a long and bitter struggle between the Oda and the Buddhist fanatics of the Ikkô-ikki, whose well trained fighting men were the equal of any daimyô’s army.

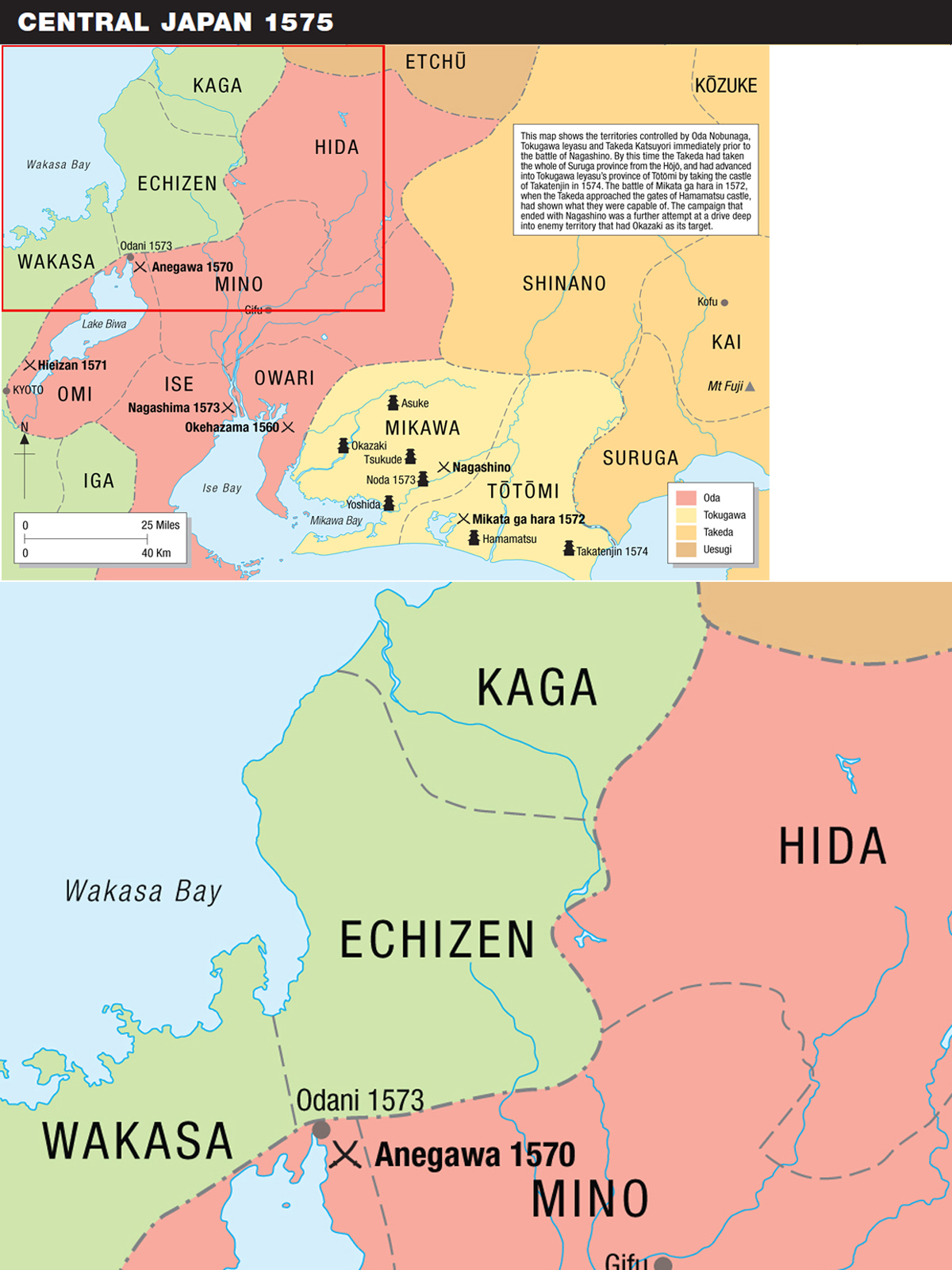

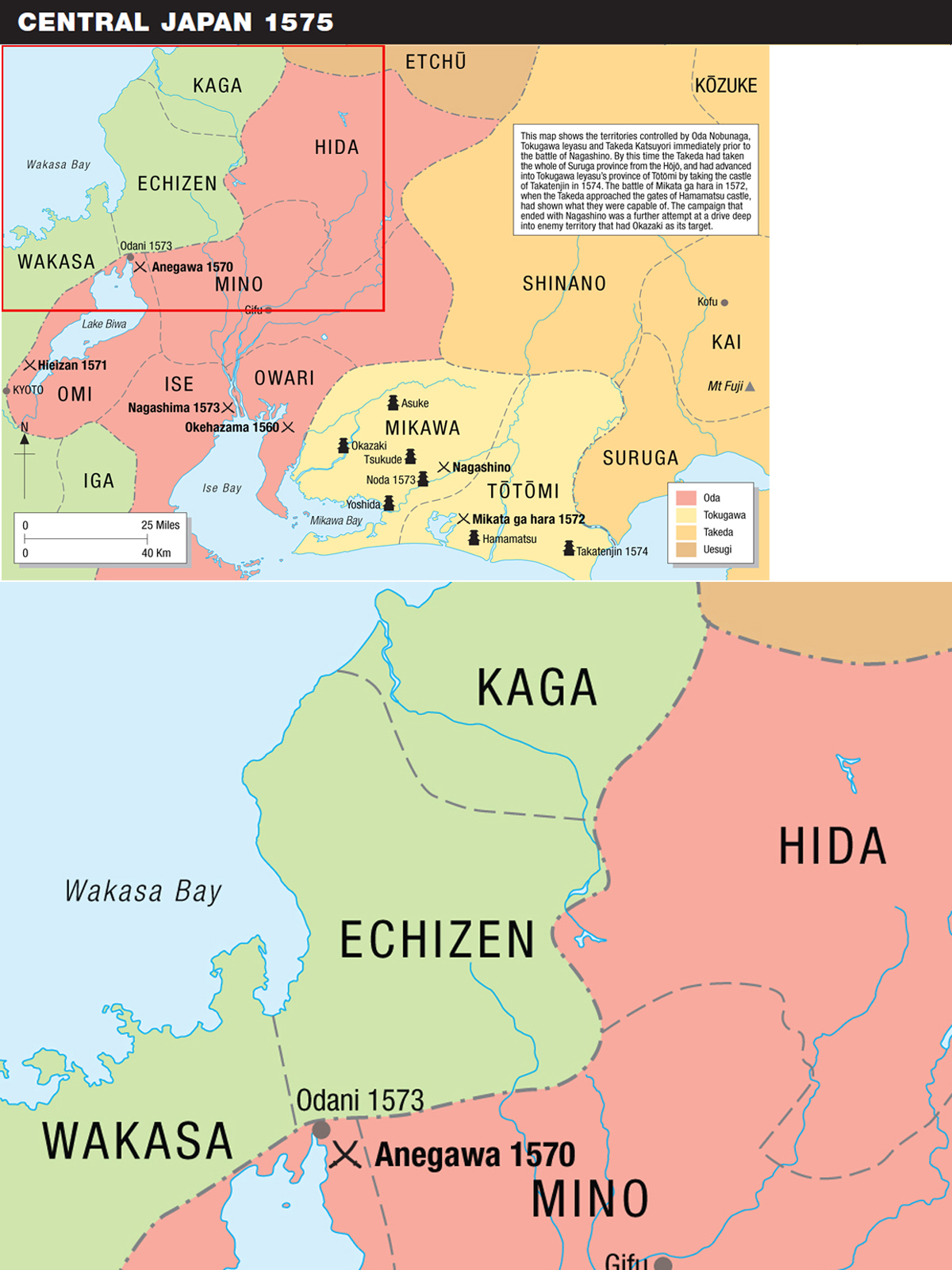

In spite of having control of the Shogun, Oda Nobunaga still effectively ruled only a handful of provinces around the capital in central Japan, and some very powerful enemies lay just over the horizon. To the west were the Mori, who controlled the Inland Sea, to the north were the Uesugi, and to the east were the mighty Takeda, under their daimyô, Takeda Shingen.

Of all the daimyô who had the potential to rule Japan, Takeda Shingen had demonstrated his ability most clearly by his own successful hegemony in Kai and Shinano provinces. Three factors had prevented him from taking the same initiative of marching on Kyoto as had been exercised by Imagawa Yoshimoto in 1560. The first was the isolation of his mountain-based province from the central area. The second was the fact that any advance by Shingen down towards the Tokaido, the road which ran along the Pacific coast, was monitored and blocked by Oda Nobunaga’s allies the Tokugawa. Finally, for much of his reign Takeda Shingen was occupied in fighting his enemies to the north and east of his own territory, in particular the Hôjô family, based near modern Tokyo, and the Uesugi, whom he contested on five occasions at the same place – the battlefield of Kawanakajima.

In the winter of 1572 Takeda Shingen broke out of his territories and made a move towards the Pacific coast. He threatened the Tokugawa in Hamamatsu castle and then defeated them when Tokugawa Ieyasu led his army out to fight him on the plain of Mikata-ga-hara. It proved to be an indecisive victory because the winter weather prevented any follow-up, but the defeat of the Tokugawa encouraged Takeda Shingen to return the following year. This time he laid siege to Tokugawa Ieyasu’s castle of Noda, on the Toyokawa river. The garrison were soon driven to the point of surrender, but, according to legend, had in their castle a large stock of sake (rice wine). Not wishing to allow this precious brew to fall into the hands of the enemy, the defenders of Noda decided to dispose of it in the most appropriate manner. The sounds of the party reached the besiegers’ ears, and Takeda Shingen was particularly taken by the music of a bamboo flute being played on the ramparts. He moved forward to hear the tune more clearly and was spotted by a sniper on the castle walls who put a bullet through his head. Takeda Shingen died a few days later, living just long enough to urge his followers to keep his death secret for as long as possible, as so much of the formidable reputation of the Takeda army rested on his own broad shoulders.

The great banner of Takeda Shingen, in a reproduction flown at Kawanakajima. It bears a quotation from the Chinese strategist Sun Zi, ‘Swift as the wind; quiet as the forest, conquer like the fire; steady as the mountain’, which became the motto of Takeda Shingen, and the inspiration of the clan. The flag was taken on the Nagashino campaign by Takeda Katsuyori.

Takeda Shingen was succeeded by his son Takeda Katsuyori, who inherited the mantle of the all-conquering Takeda daimyô and the considerable military experience of the fine Takeda army with its renowned cavalry force. It was not long before he decided to follow in his father’s footsteps by invading the territories of Tokugawa Ieyasu. He set off in 1575, but his route was different from the ones which Takeda Shingen had followed. Instead Takeda Katsuyori headed straight for the Tokugawa capital of Okazaki in Mikawa province because he had been reliably informed that a traitor there was willing to open the gates for them. However, while Takeda Katsuyori was still on his way the traitor was relieved of his head, leaving the invading army bereft of its primary target as they had insufficient strength to take Okazaki unaided. Katsuyori was forced to change his plans, and decided to capture a smaller castle as compensation. He therefore took a different road back from Mikawa, one which followed the long flat plain along the Toyokawa from the sea and up into the mountains. The road was defended by three castles. The nearest one was Yoshida, where the Toyokawa entered the sea. Yoshida withstood Katsuyori’s attack, so he turned his attentions to the point where the flat plain ended and the security of the mountains began. Here, on the edge of a cliff, lay a tiny fortress called Nagashino.