At the battle of Nagashino both sides commanded armies that were broadly similar in a number of aspects, yet had differences that were to prove crucial in the battle itself. The similarities that existed among most samurai armies had arisen from competition, so that the typical samurai army had evolved into an efficient fighting machine that possessed certain basic features. The first characteristic was a recognised structure of feudal obligation that the daimyô could transform with the minimum of effort into an army. The most important resources of fighting men came from within the daimyô’s own extended family and from among the families who were hereditary vassals, called the fudai. Next, and less reliable, were contingents supplied from neighbouring territories, such as those of a vanquished enemy. Finally, there would be allied armies who would join a daimyô’s army for a variety of reasons, usually self-interest.

This is a typical suit of armour of the Sengoku Period, such as would have been seen at many battles around the time of Nagashino. The breastplate is made of horizontal layers of iron riveted together, while the kusazuri (tassets) are of conventional kebiki-odoshi (close-spaced lacing). Note the two straightforward kote (shoulder plates) and the simple kote (sleeve armour).

The numbers of troops supplied by these different sources varied greatly in quality and quantity. The wealth of a landowner, or a fief-holder, was expressed in koku, one koku being the amount of rice thought necessary to feed one man for one year. Feudal obligation required the supply of troops according to wealth. As a rule of thumb two mounted men and 20 foot per 1,000 koku would be supplied, although the proportion varied enormously from year to year and from daimyô to daimyô. By such means the commander could assemble a host whose numbers, strength and weaponry were calculable in advance.

The elite of the daimyô’s army were the samurai themselves. The word ‘samurai’, which is nowadays taken to mean any Japanese fighting man, had a narrower definition during the Sengoku period. At that time the samurai were the knightly class who rode horses. Mounted warriors had always been an elite in Japan. The first samurai had been mounted archers, and their armour, though not unduly heavy, provided the protection they had needed as mobile ‘gun platforms’. Early samurai warfare was a matter of archery duels, concluded with sidearms, against a worthy opponent who was also of samurai rank. The samurai were attended by an equal number of lower-ranking soldiers who fought on foot and had as their primary role the support of their master rather than direct combat.

By the Sengoku-jidai there had been considerable changes in the makeup of a samurai army. Many poorer samurai either could not afford horses sor simply chose to fight on foot, and the daimyô had also realised that to augment and hold their territories they had to rely increasingly on the services of lower ranking, lower class footsoldiers. This change became apparent in the weaponry of the samurai. Exclusive use of the bow had laid the mounted samurai open to attack from bands of footsoldiers, so in time the bow was abandoned in favour of the long, straight spear, which enabled the samurai to defend himself and take the fight to the enemy in a way that the bow had not allowed. He was still attended by a group of followers, who could hand to him a bow or spear as required, but chronicles of the time and contemporary illustrations clearly show that the spear became the preferred weapon on the battlefield. When Shimazu Toyohisa rode into battle at Sekigahara in 1600 carrying a bow it was thought sufficiently unusual for the chronicler to make particular note of it.

A section of armour plate laced in the sugake-odoshi (spaced out lacing) style. The individual scales are of lacquered iron. The sugake style had the convenience of being quicker to make than the kebiki style, while losing none of its flexibility, and much armour of the time of Nagashino would have been made like this.

Most illustrations show mounted samurai spearmen wearing a rounded style of armour called a dô-maru instead of the older box-like yoroi, to which the addition of a solid breastplate was practically the only major change in design during the whole of the ‘Warring States Period’. Armour was worn on the sleeves, arms, legs and face, with a sashimono – an identifying device, frequently a flag – worn on the back of the samurai’s armour. Troops from a particular unit would wear identical sashimonos.

The type of spear the samurai carried was called a mochi-yari (held spear). The shaft length varied between 3.2m and 4m, and blade lengths varied considerably between about 10cm and 1.5m. Techniques were developed to enable the samurai to use this weapon in any situation: from a horse, in a charge on foot, or to defend castle walls. Some illustrations suggest that the spears were used as lances from the saddle, others that they were more used for slashing strokes while standing up in the stirrups. No daimyô army was better skilled at the use of mounted troops than the Takeda. The victories of Ueda, in 1548, and Mikata-ga-hara, in 1572, owed a great deal to the mobile and hard-hitting power of the devastating Takeda cavalry charge.

The Ashigaru

The footsoldiers at whom the cavalry charged were no disorganised rabble, for the daimyô realised that for footsoldiers to be of any use against samurai they had to be trained and disciplined. The original name for them – ashigaru (light feet) – changed from meaning a haphazard bunch of absconded peasants to what were effectively the ‘other ranks’ of the samurai class. The new respect for the ashigaru was shown by the practice of dressing them in uniform armour and colours. Yamagata Masakage, who fought for the Takeda at Nagashino, dressed all his army, including the ashigaru, in red-lacquered armour, yet even this apparent uniformity concealed a certain amount of rank distinction, for close examination would have revealed that the ashigaru armour was not of the quality worn by the higher ranks of samurai. It was frequently of simple construction, with the commander’s personal mon (badge) lacquered on to the front. Armoured sleeves might be included, but the ashigaru was unlikely to sport the haidate (thigh guards) or suneate (shin guards) of his betters. The biggest difference in appearance and protection, however, came with the helmet. In place of the samurai’s kabuto (helmet) and face-mask, the ashigaru wore a simple iron jingasa (war hat), which was usually shaped like a lampshade and had a cloth neckguard hanging from the rear.

A samurai body armour of solid plate construction is shown here folded out to illustrate how the five parts fit together. The kusazuri would be suspended from a row of holes around the lower edges. The ties that hold the armour together around the samurai’s body are found under the right armpit. The prominent bracket is to hold the pole of the sashimono, the identifying device (usually a flag) that was worn on the back of the armour.

A simple face mask. One of the most noticeable innovations in Japanese armour during the 16th century was the introduction of armour for the face. It commonly fitted to just below the eyes, as shown in this example, which has a removable nosepiece. The two projecting bolts under the cheeks are there to take the cords which tied the helmet on to the head. Some later examples sported whiskers made of horsehair.

The role of the footsoldier as warrior’s assistant continued, and as many as 40 per cent of the total number of troops in a typical army could be ashigaru performing simple but vital support functions such as baggage carriers, grooms and drummers. The remainder of the ashigaru force would be organised in corps of specialised weaponry: bows, spears and matchlock guns. Archers were the least in number, since prowess with the bow required years of practice as well as muscular strength. The ashigaru archers were therefore highly trained sharp-shooters, and were often employed as skirmishers. In addition, along with the matchlockmen, they could form lines of missile troops, supplied with a large number of arrows carried in 100-arrow box quivers. Archers sometimes appear to be regarded as the least important of the three arms, and in the 1575 Uesugi muster rolls they are included within the ‘other troops’ category (total 1,018), alongside 3,609 spearmen, 321 matchlockmen and 566 mounted samurai.

Spearmen were usually the largest category. Oda Nobunaga was probably the first to introduce disciplined ashigaru spear units into his army and he possessed a contingent who made up 27 per cent of his fighting force. The longest spears of all were also to be found in the Oda armies, with a giant 5.6m shaft. It seems that Nobunaga adopted them quite early on in his career, because there is a reference in the Shinchôkoki dated April 1553 to ‘500 three and a half ken [5.6m] long spears’. These nagae-yari (long-shafted spears) were probably used like pikes. Some form of ‘pike drill’ must have taken place, and there is evidence from contemporary illustrations of the ashigaru pikemen forming a hedge behind the matchlockmen to protect them. All the ashigaru units were under the command of an ashigaru-taishô (ashigaru general), which implies a high degree of discipline. Unfortunately, in the accounts of the wars, it is the lowest ranking soldiers who get forgotten, and descriptions of ashigaru warfare tend to appear as anonymous groups of weaponry. A samurai may be recorded as ‘falling prey to the ranks of spearmen’, or being ‘laid low in a hail of gunfire’, but further details of actual use have to be inferred.

Both the Takeda and Oda armies possessed firearms, and since their use by the Oda was to prove decisive, a brief discussion is needed about these weapons and how they were used prior to Nagashino. Simple Chinese handguns had been known in Japan since 1510, and in 1543 they were joined by more sophisticated Portuguese models. The island on which the Portuguese landed was owned by the Shimazu clan, and it was to Shimazu Takahisa that the honour went of conducting the first battle in Japanese history where the new firearms were used. This was in his attack on the fortress of Kajiki, in Osumi province, in 1549. He was one of several warlords to appreciate the potential shown by these new weapons, and local swordsmiths, who were already renowned for their metal-working skills, applied themselves to learning how to copy the arquebuses and then to mass produce them. Connections with Portuguese traders also proved very important, and it is no coincidence that the first Christian converts among the samurai class became regular users of arquebuses. Oda Nobunaga’s support for Christian missionaries was a great help in this regard.

A samurai holding a spear, with the support for a sashimono clearly visible on the back of his armour. Regardless of the prestige and lore associated with the Japanese samurai sword, a spear was the preferred primary fighting weapon on the battlefields of 16th century Japan. The spear was skilfully wielded from horseback, but was also employed on foot and in sieges. The armour in this photograph is of nuinobe-do style, and is decorated on the edges with black fur.

The Portuguese arquebus was a simple but well designed weapon. Unlike the heavier type of muskets which required a rest, the arquebus could be fired from the shoulder, with support needed only for the heavier calibre versions which the Japanese later developed – usually known as ‘wall guns’ or ‘hand cannon’. In a normal arquebus an iron barrel fitted neatly into a wooden stock. To the right of the stock was a brass serpentine linked to a spring which dropped the serpentine when the trigger was pulled. The serpentine contained the end of a glowing and smouldering match, the rest of which was wrapped around the stock of the gun, or wound around the gunner’s arm. Arquebuses are therefore often called simply ‘matchlocks’. To prevent premature explosions, the pan, into which the fine priming gunpowder had been carefully introduced, was closed by a brass sliding cover which swung back at the last moment. The guns produced quite a recoil and a lot of smoke, as shown in the annual festival at Nagashino, where reproduction matchlocks are fired. As time went by cartridges were introduced, thus speeding up the process of loading.

A Portuguese adventurer wrote that within two or three years the Japanese had succeeded in making several hundred guns, and by the 1550s they were regularly seen in action in battle. The best gunsmiths formed schools to pass on the tradition, such as those at Kunitomo and Sakai, and were never short of customers. Within the space of a few years arquebuses were being produced to quality standards that exceeded those originally brought from Europe. One simple, yet fundamental, development which occurred quite early on in Japanese arquebus production was the standardisation of the bore. In Europe, where no form of standardisation was carried out, practically every gun needed its own bullet mould. In Japan, bores were standardised to a handful of sizes. Standard bores meant standard sized bullets which could be carried in bulk for an arquebus corps – a small, but significant improvement in production and use.

The classic daisho (pair of swords) that was the badge of the samurai class. The longer was called a katana, and the shorter was known as the wakizashi. In armour the katana alone would be worn, slung from a scabbard-carrier attached to the belt, where it would be accompanied by a tanto (dagger). By the end of the 16th century the Japanese sword had acquired the mystique it still enjoys today, and fine specimens were highly prized and very expensive.

A quick way of getting into a suit of armour was by supporting the body armour, to which the sleeves had already been attached, from the ceiling with a rope. The samurai then clambered in. He is already wearing his haidate (thighguards) and his waraji (straw sandals), so he will be soon ready for battle.

In 1549 Oda Nobunaga placed an order for 500 arquebuses with the gunsmiths of Kunitomo. In 1555 Takeda Shingen used 300 in an attack on a castle owned by Uesugi Kenshin and was so impressed that he placed 500 arquebuses in one of his own castles. However, few daimyô appreciated that the successful employment of firearms depended only partly on technical matters such as accuracy of fire and speed of loading. Just as was the case in Europe then, in the time it took to fire a succession of arquebus balls a skilled archer could launch many more arrows, and with considerably more accuracy. On the other hand, to use a bow properly required an elite archer corps, but the arquebus could be mastered in a comparatively short time, making it the ideal weapon for the lower ranking ashigaru.

The secret to success with firearms was therefore the same as the secret of success with any infantry unit: good army organisation and a considerable change in social attitudes. To achieve this there first had to be a recognition that the ashigaru could be more than a casually recruited rabble, and a commitment had to be given to their training and welfare. This had been achieved by both the Takeda and the Oda prior to 1575, but it took a further leap of the imagination to give them pride of place in a samurai army, because traditionally the vanguard of an army had always consisted of the most experienced and trusted swordsmen and mounted samurai. Yet for firearms to be effective they had to be placed in the front ranks in large numbers. All that was needed was a demonstration of how successful this method could be.

Oda Nobunaga had already used a volley-firing technique at Mureki in 1554. It had also been used against him by the Buddhist fanatics of the Ikkô-ikki at their fortress cathedral of Ishiyama Hongan-ji, built where Osaka castle now stands. Nobunaga’s first move against the Ishiyama Hongan-ji was launched in August 1570. He had established a series of forts around it, but on 12 September the bells rang out at midnight from within the Ishiyama Hongan-ji and two of Nobunaga’s fortresses were attacked. The Oda army were stunned both by the ferocity of the surprise attack and by the use of controlled volley firing from 3,000 matchlock men. This little known battle pre-dates Nagashino by five years and was probably the first example of large scale organised volleyed musket fire used in battle in Japan. In the chronicle Shinchôkoki we read that the enemy gunfire ‘echoed between heaven and earth’, resulting in the withdrawal of the Oda main body, leaving a handful of forts to attempt the task of monitoring, if not controlling, the mighty fortress of Ishiyama Hongan-ji – a process that would take 11 years and much of Nobunaga’s military resources.

This encounter provided an excellent demonstration of how matchlocks might best be employed, and it is surely no coincidence that it came from the Ikkô-ikki. Being composed largely of lower class troops, their mere existence proved the power of well organised ashigaru armies, and their use of firearms was simply one very dramatic way of expressing it. Lacking any of the social constraints likely to impede a samurai’s appreciation of the potential combination of ashigaru and guns, the monk armies simply adopted a new weapon on military grounds alone. Showing the ability to learn from experience that was to mark his career, Oda Nobunaga put his own arquebuses into action against the Ikkô-ikki fortress of Nagashima in 1573. Copying the monks’ techniques, Nobunaga hoped that concentrated arquebus fire would blast a way into the fortress for him. However, the defenders were saved by a sudden downpour which soaked the matches of the Oda guns, rendering nine out of ten non-fireable, and the attack failed. This was another military lesson not to be lost on Oda Nobunaga.

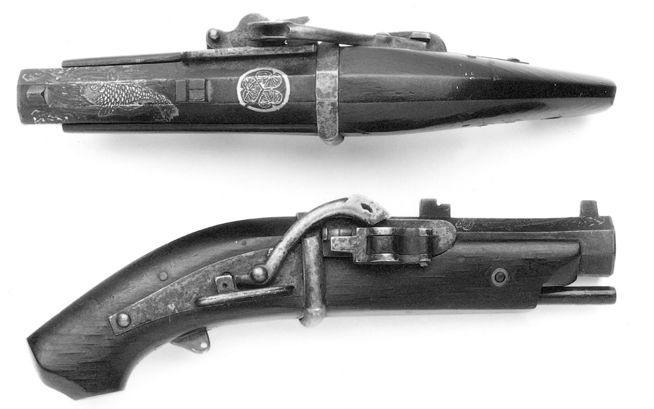

A miniature arquebus, showing details of the touch hole and serpentine. The touch hole is covered by a hinged brass cover to guard against premature explosions. The smouldering match would fit into the end of the serpentine, and the ramrod slid under the barrel. This example bears the mon (badge) of the Tokugawa on top of the barrel.

Any Sengoku battle tended to be fought between alliances of clan armies, set out according to an agreed battle plan and co-ordinated through the mobile tsukai-ban (messengers). Each clan army was further subdivided into weapon groups, and co-ordinated through its own band of tsukai. Within each army fought high-ranking mounted samurai spearmen who each supplied a handful of personal retainers according to their means. Other samurai retainers fought on foot with spears, supported by ashigaru. Specialised corps of highly trained ashigaru wielded bows or arquebuses, and all were under the command of officers. A sizeable support unit was included in each army. Flag bearers were the most important element of this unit and had their own guard. Within each clan army there would be a large headquarters unit who formed the lord’s bodyguard. Careful strategic planning, with the co-operation between separate clan armies facilitated by a skilled battlefield communication system, enabled a successful commander to control synchronised movement by units who were physically separated, with each man knowing his role in the endeavour. Both Oda Nobunaga and Takeda Shingen possessed sufficient resources to support such a model by supplying and training their armies. This ensured the continuing loyalty of their men.

A mounted samurai, adorned with severed head trophies. Since ancient times the one sure proof that a samurai had done his duty was by the presentation to his lord of the heads of his defeated enemies. This warrior has a fine collection of four heads in all, one of which is still stuck on his spear blade. He has slung his helmet over his shoulder, and is wearing the samurai’s jinbaori, a form of sleeveless surcoat. Arrows are protruding from his armour.

The overall number of troops in the conflict was as follows:

| Oda Nobunaga | 30,000 |

| Tokugawa Ieyasu | 8,000 |

| Okudaira Sadamasa (the Nagashino garrison) | 500 |

| Takeda Katsuyori | 15,000 |

Oda Nobunaga, who was then the strongest daimyô in all Japan, had a total army of 100,000, from which he committed 30,000 (30 per cent) to the relief of Nagashino. Many of the others were still actively engaged in the long war with the Ikkô-ikki. The contingents present at Nagashino were organised along a pattern common to all daimyô – of relatives, vassals and others. The names of the leaders who appear under the various categories are as follows:

Ichizoku-shû (the family corps)

Oda Nobutada (1557-1582) (the eldest son of Nobunaga)

Oda Nobuo (1558-1630)

(Nobunaga’s second son, adopted into the Kitabatake family in 1569)

Go-umamawari-shû (bodyguard)

The bodyguard contained the elite of Nobunaga’s army and was divided into three separate units:

1. Hashiba Hideyoshi – a unit commanded by Nobunaga’s ablest general, later to be known as Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the man who would succeed in unifying Japan.

2. Kuro horô-shû (the black horô unit). A horô was a stiffened cloak worn on the back of armour by mounted men in place of the more usual flag sashimono. It was given a rounded shape by being stretched over a light bamboo framework. The men of the black horô unit present at Nagashino were Kawajiri Hidetaka, Sasa Narimasa and Nogamura Sanjurô.

3. Aka horô-shû (the red horô unit). Five of this elite corps took part in the battle: Maeda Toshiie, Mori Kawachi-no-kami, Kanamori Nagachika, Fukutomi Hiraza’emon and Harada Naomasa. The members of both horô-shû would have had a few attendants each but no other troops, since at Nagashino they were placed in charge of the matchlockmen.

Fudai-shû (hereditary vassals)

Niwa Nagahide

Sakuma Nobumori

Shibata Katsuie

Tozama-shû (the ‘outer lords’)

Takigawa Kazumasu

Nagaoka Fujitaka

Akechi Mitsuhide

Andô Noritoshi

Mori Yoshinari

Unfortunately the numbers of each contingent are not known. The Oda army had 3,500 matchlocks, all of which were taken to Nagashino. Five hundred were sent on the dawn raid on Tobigasuyama, leaving 3,000 to face the Takeda cavalry.

A selection of different sizes of arquebus, ranging from ones that are virtually matchlock pistols to very long specimens. Note the prominent sight fitted to the barrel. The long arquebuses have external springs of brass, operated by the trigger to lower the serpentine, while on the smaller ones the springs are set inside the stock.

Tokugawa Ieyasu supplied 8,000 men out of his total of 12,500, which was 64 per cent – a large commitment of resources as they were his territories that were being attacked. As many of his other troops were holding castles that were also under threat from the Takeda, almost the entire Tokugawa army was engaged in some way or another in the struggle with Katsuyori. The Tokugawa structure resembled that of the Oda. The relatives and fudai appeared in two units, one for western Mikawa province, the other for eastern Mikawa. Commanders present at Nagashino were as follows:

Spearmen in action. This detail from the Ehon Taikô-ki shows an encounter in the form of a mock battle between two groups of spearmen, which was arranged to show the superiority of long shafted spears over short ones. The maku (field curtains) bear the mon of Oda Nobunaga.

Under Ishikawa Kazumasa (commander of western Mikawa)

Matsudaira Kiyomune

Matsudaira Nobukazu

Matsudaira Tadatsugu

Naitô Ienaga

Hiraiwa Chikayoshi

Under Sakai Tadatsugu (commander of eastern Mikawa)

Matsudaira Tadamasa

Matsudaira Ietada

Honda Hirotaka

Nishikyô Iekazu

Okudaira Tadayoshi

Suganuma Sadamitsu

Hatamoto (headquarters troops)

Honda Tadakatsu

Sakakibara Yasumasa

Okubo Tadayo

Torii Mototada

plus others.

Again, no numbers are available for individual commanders.

It is possible to be much more precise about the composition of the Takeda army at Nagashino. The great chronicle of the Takeda, the Kôyô Gunkan, contains a very detailed breakdown of the clan army during the time of Shingen. Each named individual is listed along with the number of horsemen he supplied to the Takeda army, and it is unlikely that these numbers changed at all with the succession of Katsuyori. Since there are very good records of the names of samurai leaders present at Nagashino, it is a straightforward task to look each one up in the Kôyô Gunkan and thus compute the size and make-up of the Takeda force. To do this I have used the list in Futaki’s book Nagashino no tatakai and added the number of horsemen from the Kôyô Gunkan. The sub-divisions of the army are similar to that of the Oda and Tokugawa, and consisted of three overall parts: jikishindan, sakikata-shû and kuni-shû. The kuni-shû (provincial corps), levies from the villages, were not represented at Nagashino. Of the others, those present at Nagashino are listed as follows under the commanders’ names. Further biographical details of the commanders themselves appear in a later chapter. In several cases only the surnames are known.

The jikishindan (the ‘close retainer’ group) was subdivided into four:

| 1. Goshinrui-shû (relatives group) | |

| Anayama Nobukimi | 200 |

| Ichijô Nobutatsu | 200 |

| Takeda Nobukado | 80 |

| Takeda Nobumitsu | 100 |

| Takeda Nobutoyo | 200 |

| Takeda Nobutomo (presumably in a personal capacity only) | 0 |

| Takeda Nobuzane | 15 |

| Takeda Katsuyori (his personal force) | 200 |

| Mochizuki Nobumasa | 60 |

Each of the above horsemen would have worn the Takeda mon on their sashimono, while the leader’s personal banner would have had its own device.

| 2. Go fudai karo-shû (fudai and elders) | |

| Atobe Katsusuke | 300 |

| Amari Nobuyasu | 100 |

| Oyamada Masayuki | 70 |

| Oyamada Nobushige | 200 |

| Kosaka Masazumi | 20 |

| Tsuchiya Masatsugu | 100 |

| Naitô Masatoyo | 250 |

| Hara Masatane | 120 |

| Baba Nobuharu | 120 |

| Yamagata Masakage | 300 |

These men fought under their leader’s personal banner rather than the Takeda mon.

| 3. Ashigaru-taishô (generals of ashigaru units) | |

| Obata Matagorô | 3 (+10 ashigaru) |

| Obata Nobuhide | 12 (+65 ashigaru) |

| Saigusa Moritomo | 30 (+70 ashigaru) |

| Saigusa Ujimitsu | 3 (+10 ashigaru) |

| Shimosone Masamoto | 20 (+50 ashigaru) |

| Tada Jiro`emon | 0 (+10 ashigaru) |

| Nagasaka Juza`emon | 40 (+45 ashigaru) |

| Yokota Yasukage | 30 (+100 ashigaru) |

Three ashigaru holding spears. The most important weapon groups of ashigaru were guns, spears and bows. The two jingasa being worn here are of different styles. That on the viewer’s left is the usual conical design, while that on the right has a curved brim, and is known as the shingen style, after Takeda Shingen. This shape was worn during the Edo period by officials of the Shogun, and were made of lacquered papier-mâché. The ashigaru wear simple okegawa-dô armours.

4. Hatamoto-shoyakunin (bodyguard and servants) - see below

5. Sakikata-shû

The sakikata-shû (the ‘companions group’) consisted of men supplied by the leaders of the provinces that had been made Takeda fiefs following conquest. All had proved their loyalty thus far by good service. They are listed by province:

| SHINANO PROVINCE | |

| Sanada Nobutsuna | 200 |

| Sanada Masateru | 50 |

| Imogawa Ennosuke | 60 |

| Tokita Tosho | 10 |

| Matsuoka Ukyô | 50 |

| Muroga Nobutoshi | 20 |

| Unnamed | 60 |

| WESTERN KOZUKE PROVINCE | |

| Obata Nobusada | 500 |

| Annaka Kageshige | 150 |

| Wada Narimori | 30 |

| Unnamed | 14 |

| SURUGA PROVINCE | |

| Asahina Nobuoki | 150 |

| Okabe Mastsuna | 50 |

| Okabe Unsei | 10 |

| Unnamed | 9 |

| TÔTÔMI AND MIKAWA PROVINCES | |

| Suganuma Sadanao | 40 |

| Others | 3 |

Kôsaka Masazumi, of the fudai karo-shû is allocated a notional 20 horsemen because at the time of the departure of the Mikawa invasion, Kôsaka Danjô Masanobu, one of the Takeda’s most illustrious generals, was already in arms against Uesugi Kenshin, accompanied by an army of 10,000. Presumably that included his own 450 horsemen. Two Kôsakas – Sukenobu and Masazumi – fought at Nagashino, and both were killed, but there is no separate record of horsemen under their names.

The total of all horsemen supplied in the army that went to Nagashino is 4,199, to which we must add the 55 named individuals above (some families supplied two or three as commanders). This brings the total to 4,254. The total for all the horsemen in the Takeda army in the Kôyô Gunkan list is 9,121, which means that the Nagashino force was 47 per cent of the total mounted Takeda army.

Turning to the composition of the complete army, every horseman would have been accompanied by two followers on foot. Takeda Shingen had a personal retinue of 884 ashigaru and servants, who made up the hatamoto-shoyakunin. To this were added various notable samurai from the list above as a bodyguard.

It seems reasonable to assume the same numbers for Katsuyori, and there were, in addition, 5,489 other ashigaru under the command of the other leaders, including the ashigaru-taishô’s own command. These figures would give a full Takeda army of 33,736, as follows:

| Horsemen | 9,121 |

| Two followers each | 18,242 |

| Ashigaru in the hatamoto-shoyakunin | 884 |

| Other ashigaru | 5,489 |

| Total | 33,736 |

Since we have established that 47 per cent of the Takeda army took part at Nagashino it seems not unreasonable to apply the same percentage to the figures for ashigaru, including the bodyguard unit, as presumably some would stay behind to guard Katsuyori’s family in the headquarters in Kofu. The Nagashino army therefore becomes 15,757 men, distributed as follows:

| Horsemen | 4,254 |

| Two followers each | 8,508 |

| Ashigaru in the hatamoto-shoyakunin | 415 |

| Other ashigaru | 2,580 |

| Total | 15,757 |

This number tallies well with accounts of the battle, which have the army at about 15,000. The deployment of just under half the Takeda army reflects their need to conduct a campaign against the Uesugi at the same time. It also points to the initial aim of Takeda Katsuyori, which was to capture Okazaki in a rapid raid using the treachery of a Tokugawa official.

The figures show that 27 per cent of the Takeda army at Nagashino were mounted samurai, while 4 per cent (655 men) had arquebuses. This shows the great reliance the Takeda placed on their cavalry arm. A later chapter will show how these 4,254 horsemen were distributed during the charge at the Battle of Nagashino. For now it is sufficient to note that 125 of the above stayed in the siege lines, leaving 4,031 to take part in the assault on the Oda-Tokugawa lines, where there were 3,000 matchlockmen waiting for them. There were therefore three ashigaru matchlockmen on the Oda side for every four Takeda mounted samurai charging them. Under normal circumstances a cavalryman, if he survived the ashigaru’s one shot, would be upon the shooter within seconds. The crucial difference at Nagashino lay in how the ashigaru were to be used.

It is dawn on the first full day of the siege of Nagashino. The castle is rising from an early morning mist that hangs along the river, and as visibility increase so the firing becomes more rapid from both sides. The view is from the south, looking across the gorge at its deepest point, the spot where Torii Sune’emon was destined to make his brave gesture. Here the siege lines are seen in close up. There are bundles of green bamboo and wooden shields from which the weary Takeda footsoldiers shoot arrows and fire guns. They are joined by three Takeda generals. Anayama Nobukimi, who is also a monk, Sanada Nobutsuna and the veteran Yamagata Masakage, whose hair is white. The details of their appearance and armour are taken from painted scrolls preserved in the Erin-ji temple near Kofu, the Takeda headquarters.