The site of the castle of Nagashino is located within Hôrai town, named after the Hôrai-ji, a prominent local Buddhist temple. It lies about 24km north-east of the city of Toyohashi. The modern road follows the Toyokawa upstream, and it is at Nagashino that the vast, wide and flat rice fields begin to give way to forested mountains and the agricultural fields become terraced. The road narrows here and begins to climb beyond Nagashino into the foothills of what was the province of Shinano, the territory of the Takeda.

The castle of Nagashino dated from 1508, and had been originally constructed by Suganuma Motonari, a vassal of the Imagawa and one of the three powerful families of the eastern Mikawa area. Because of its strategic importance as the northern gateway to Mikawa province Nagashino had been captured by Takeda Shingen in 1571, and had then been returned to the Tokugawa in 1573. By 1575 it was still a Tokugawa possession, and Okudaira Sadamasa was formally appointed as keeper of Nagashino castle in early April. The castle was under his command during the siege, when he was assisted by Matsudaira Kagetada and his son Matsudaira Koremasa. The garrison consisted of 500 men whose equipment included 200 matchlocks and at least one cannon.

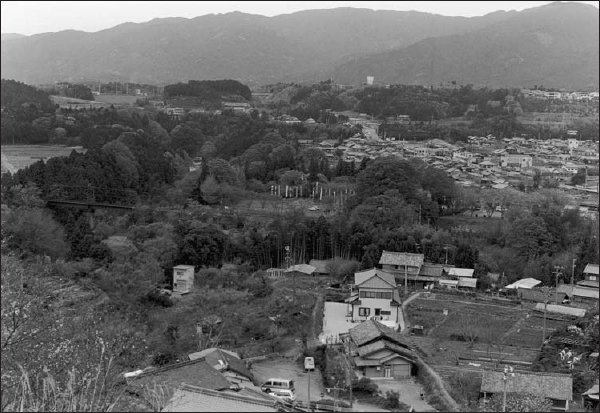

A distant view of the temple of Daitsûji, the forward point of the Takeda siege lines. The road just in front of the temple building marks the approximate position of the outer defence works of the castle of Nagashino, known as the Fukube-maru. This area was the first to be lost to the Takeda assault. The hills were just as wooded during the siege.

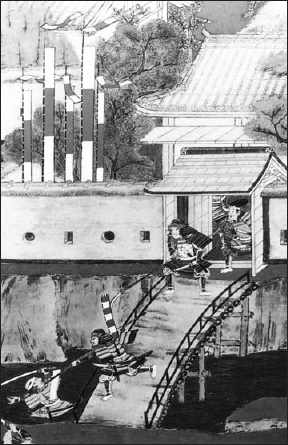

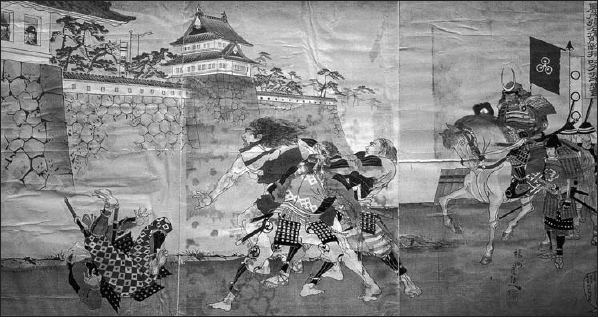

Details of the gate and walls of Nagashino castle, as depicted on a modern copy of the famous Nagashino screen. The artist has shown a bridge crossing the Onogawa to the area of Tobigasu, but this is unsupported by historical evidence. The simple walls, plastered with clay and pierced by apertures for guns and bows, are probably accurate. The walls are topped with thatch rather than tiles.

The site of Nagashino castle is a naturally strong defensive position. It is here that the two rivers Takigawa and Onogawa join in the shape of a letter ‘Y’ to become the Toyokawa, and at this point their banks are cliffs of 50m high and about 50-60m apart. The castle site is therefore a triangular piece of rocky land protected on two sides by cliffs and water. From a military point of view its weakest edge was the landward side to the north and north-west, where swampy ground ran up to the forested hill of Datsûjiyama. Here the road to the north continued on into the mountains.

The castle site is very well preserved to this day, and the building of a single-track railway round its edge has served to conserve the area rather than to destroy it. Its historical importance has long been realised, and the immediate surrounding area is kept as an open field, the museum being the only building to encroach on the site.

The castle which existed in 1575 would have borne little resemblance to the graceful white buildings on stone bases which characterise surviving Japanese castles such as Himeji and Hikone. Instead its buildings were of a simple wooden construction with wooden boarded roofs. Stone was used only for the outer walls. The fortified area was small in size, being restricted by the cliffs, and the site of the preserved hon-maru (inner bailey) is 330m from east to west and 250m from north to south. At the time of the siege approximately one third of the area – that to the east which was on lower ground terraced out from the hill – was separated off into an enclosure called the Yagyû-guruwa. The term ‘guruwa’ simply means an area enclosed by earthworks. From the Yagyû-guruwa a gate, called the Yagyû-mon, afforded access down the cliff side to the river. In 1575 the whole area of the hon-maru was defended by a stone wall and a dry moat.

In addition to the hon-maru, the original castle also had a series of outer defences, the ni no maru (second bailey), known as the Obi-guruwa, and the san no maru (third bailey), called the Tomoe-guruwa. The gate from the third bailey was called the Tomoejiro-mon. All three baileys were protected on the western side by a rapidly flowing mountain stream which cascaded into the Takigawa. The stream was crossed by a bridge to an area of flatland where the defenders had established two further enclosures – an inner one protected by a wall and earthwork, called the Danjô-guruwa, and an outer one, defended only by dry moat and a partial section of wall, called the Hattori-guruwa. Here a gate called the Ote-mon led to the west. To the north the final enclosure which lay outside the san no maru and led almost to the slopes of Daitsûjiyama was called the Fukube-maru (the Fukube barbican). It stretched as far as a little stream where there was a wall and a bridge leading from a gate called the Karamete-mon – which just means ‘the rear gate’. The wall continued up into the trees on Daitsûjiyama, as did the wall of the Hattori-guruwa on the western side. As long as the heights of Daitsûjiyama were held by the defending army, this area covered the road to the north and added greatly to the castle’s defences.

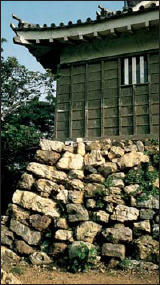

A corner tower of the castle of Hamamatsu. Nagashino castle made some limited use of stone in its defences – probably low sloping earth mounds like this one, which is faced with rough blocks. The wooden walls are also likely to have looked like this example, but without the elaborate eaves and roofing.

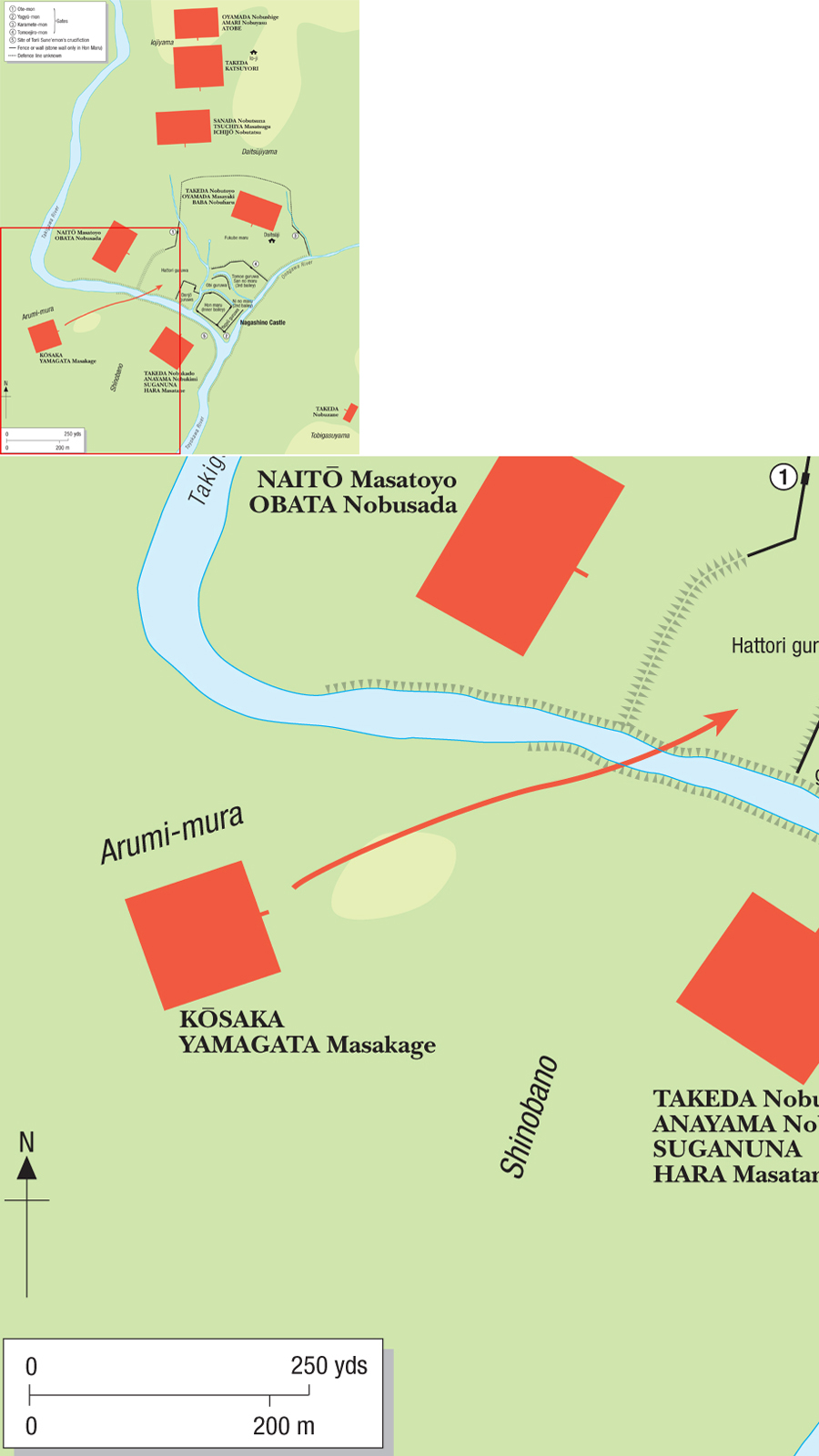

Takeda Katsuyori decided to abandon the siege of Yoshida castle on 14 June, and all his army were at Nagashino by about 16 June. In the expectation of a quick and easy victory he drew up his army in eight divisions ready for attack. Katsuyori clearly appreciated the nature of the castle’s layout, and made a point of securing the hills of Daitsûjiyama and Iojiyama with a large number of troops. From there an attack could be mounted on the Fukube-maru. The hill of Iojiyama, beside which stood the temple of Io-ji, lay about 1km from the Ote-mon of the castle and in 1575 afforded an uninterrupted view of Nagashino, so this became Kaysuyori’s headquarters where he stationed his personal contingent of 3,000 men. On the reverse slope of Iojiyama were Amari Nobuyasu and Oyamada Nobushige with 2,000 men as a rearguard. The vital forward area of Daitsûjiyama was covered by the veteran generals Takeda Nobutoyo, Baba Nobuharu and Oyamada Masayuki and their 3,000 troops.

To the north-west of the castle, on the flatlands beyond the Hattori-guruwa, were Ichijô Nobutatsu, Sanada Nobutsuna and Tsuchiya Masatsugu, again with 3,000 men. To the west, on the eastern bank of the Takigawa and closer to the Hattori-guruwa, were Naitô Masatoyo and Obata Nobusada with 2,500 men. The other divisions faced the castle from across the rivers. To the south of the Takigawa, in the triangular area between the Takigawa and the Toyokawa known as Shinobano, were Takeda Nobukado, Anayama Nobukimi (known better by his later Buddhist name of Anayama Baisetsu), Hara Masatane and Suganuma Sadanao with 1,500 men. To the south-west of the Takigawa, in the area called Arumi-mura, were stationed Yamagata Masakage and Kosaka Masazumi with 1,000 samurai and other ranks as a reserve corps. To the east, across the Onogawa and occupying the hill of Tobigasuyama, was the solitary division of Takeda Nobuzane with 1,000 men.

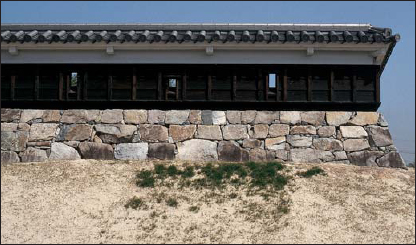

The low walls of Shôryûji castle, set upon an earth mound and topped with a wooden palisade, are typical of the mid-Sengoku period, so we may envisage parts of Nagashino castle looking like this. Shôryûji lies mid way between Kyoto and Osaka, and has recently been excavated. The outer walls have been rebuilt to enclose a public park.

The first fighting of the siege of Nagashino occurred on 17 June, when some Takeda samurai tested the mettle of the defenders with an attack on the Ote-mon to the north-west. The following day the attack began in earnest as Takeda Katsuyori ordered an all-out assault under the cover of taketaba (shields made from bundles of bamboo). The defenders counter-attacked vigorously and set fire to the taketaba. According to the Nagashino nikki account, the bullets and arrows from within the castle caused 800 casualties among the Takeda troops. This encounter began a contest of arms that was to last with hardly a break for an exhausting four days. The garrison, although outnumbered by 30 to one, put up stiff resistance as the chronicles record. Bullet was met by bullet, and spear by spear. Early in the activity (the date is not given, but it was probably 19 June) the Takeda showed great ingenuity in their attempts to break down the defences of Nagashino castle. One potential weak point was the Yagyû-mon, the gate which led out to a cliff path down to the river on the castle side. The river was almost impossible to cross at that point, so the Takeda constructed a wooden raft and floated a detachment of soldiers down the Onogawa towards it. The defenders first greeted the sluggish craft with a hail of arrows and bullets and then with rocks, and the raft was sunk before it had a chance to be moored. It would certainly appear from this incident that the river in 1575 had much more water in it than it does today. Nowadays it would be impossible to float a raft down it at this time of year.

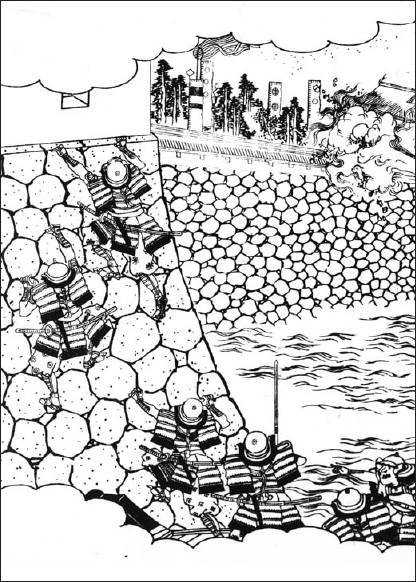

An attack on the walls of a Sengoku castle, as shown in a detail from the Ehon Taikô-ki which refers to one of the forts in the area of the battle of Shizugatake. Long spears are thrust forward to break open the clay surface of the ‘wattle and daub’ walls. They also seem to have provided a convenient ladder for the samurai who is climbing over the tiled tops of the defences.

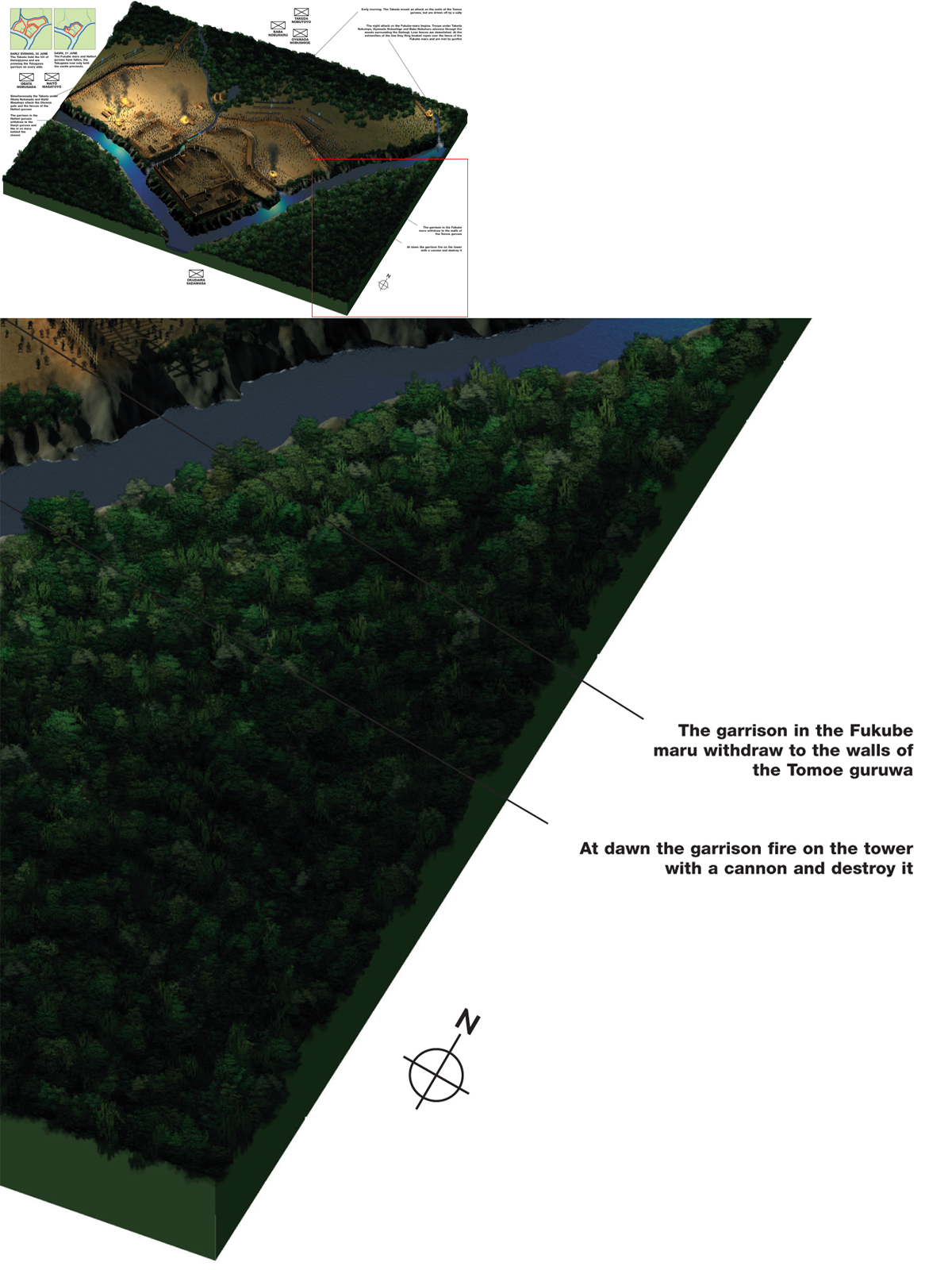

On 20 June the Takeda launched a night attack from two sides. The sky was cloudy, obscuring the moon, and under cover of pitch darkness the Takeda assaulted the Fukube-maru. This area measured 136m from east to west and 90m from north to south. There were no earthworks, only a wooden fence. However, it was bordered on one side by cliffs and on the other by boggy land, and it was also under the eyes of the defending garrison in the Tomoe-guruwa, who were able to cover it with gunfire. It was thus a location advantageous to hold, but would not necessarily prove a disaster if it were relinquished. Taking advantage of the darkness the Takeda troops flung hooked ropes on to the stockade walls and hauled themselves over into the Fukube-maru. Here they were met by a hail of arrows and bullets from the defenders. However, the numerical superiority of the Takeda told, and Okudaira Sadamasa ordered a withdrawal to within the Tomoe-guruwa, from which a counter-attack could be mounted. The Fukube-maru was thus effectively abandoned to the Takeda.

At the same time an attack was made against the Ote-mon, the gate to the west from the Hattori-guruwa, and Okudaira Sadamasa was forced to make the same difficult decision of withdrawing from these outer defences and pulling back into the earthworks of the castle itself. The area of the Hattori-guruwa and the Fukube-maru, which was continuous with Daitsûjiyama, had now become a ‘no man’s land’ between the two sides. That same night the Takeda began the rapid construction of a siege tower from large diameter tree trunks. This would provide them with a platform from which they could look down into the castle itself from just outside the defences. The tower and its construction work were protected by taketaba. The work went on all night, and as dawn broke on 21 June the final rope holding it up was secured. The defenders’ response was immediate, for they had in the castle a cannon capable of firing a shot of 15-20kg. This opened up on the tower and scored a direct hit, smashing it to pieces.

The loss of the tower did not reduce the ferocity of the Takeda attack. The besiegers now controlled the former Fukube-maru and from there were able to press home attacks against the Tomoe-guruwa. This provoked a sally from within the castle, led at spear-point by Yamazaki Zenshichi, Okudaira Izumo, two samurai called Shoda and Kuroya and others. The attackers were temporarily driven off for the loss of ten casualties from within the garrison.

Early that same morning there occurred a remarkable incident described in one of the chronicles. A certain samurai called Toda Tôgorô, who was under the command of Matsudaira Matashichirô, was devoted to the worship of Hachiman, the Shinto god of war. That morning he descended the path from the Yagyû-mon to the river, where he performed cold water ablutions and prayed to Hachiman for good fortune in war. He was spotted by an enemy general, who sent a samurai down to the river to despatch him, but the Takeda warrior missed his footing and fell into the water. Taking this as a sign of the god’s goodwill, Tôgorô tackled the man and cut off his head, taking it back as a trophy and dedicating it, appropriately enough, to Hachiman.

Samurai attack a moated castle. Nagashino probably did not possess the sophisticated stone walls shown in this picture, but it nonetheless gives a good impression of the determination of samurai to be the first into battle during a siege. Patience was not a recognisable samurai virtue.

On the nght of 20 June the Takeda forces launched an attack on the castle from two sides, these attacks carried on until the dawn of the 21st.

The area of the former castle of Nagashino is well shown in this distant view. The houses of the town of Horai fill the area that was formerly the second and third bailey, the Obi-guruwa and the Tomoe-guruwa. The railway bridge crosses the Takigawa along the edge of the hon-maru (inner bailey), which is remarkably well preserved.

This was the only good fortune Hachiman was to send that day, 21 June, because later that morning there was a new and alarming development in the garrison’s fortunes. One of the strengths behind the Takeda economy was the existence of gold mines in the mountains of their provinces. Many gold miners had been drafted into the Takeda army for their tunnelling skills, and they had been hard at work since the siege began. There was a high stone wall at the western corner of the hon-maru, and on the morning of 21 June a section of it collapsed, making a considerable noise. The damage was not total, but had a considerable psychological effect on the Nagashino garrison, who had now been fighting continuously for four days and nights. The Takeda had rotated their troops, a luxury which the 500-strong garrison could not afford. Instead, between attacks they had needed to work at strengthening or shoring up their defences by excavating a dry moat around the hon-maru and using the soil for another earthwork wall.

As expected, a furious attack followed the mining, and 21 June saw the fiercest and most intense fighting of the siege. By evening the defenders had lost to the Takeda both the third bailey and the Danjô-guruwa, the earthwork that had been the only extension of the castle left projecting across the stream on the western side. All that was left of Nagashino castle was now the area covered by the hon-maru, the Yagyu-guruwa and ni no maru. Most importantly, the Takeda had succeeded in destroying the castle’s storehouses.

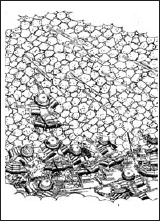

Climbing a castle wall. This dramatic detail from the Ehon Taikô-ki shows the indomitable samurai spirit at its best, as the warriors clamber up the rough stone wall like so many black beetles, oblivious of the hail of arrows pouring down on top of them.

By this time both sides were growing tired. Having failed with towers, mines and rafts after five days of fighting, Takeda Katsuyori was beginning to realise that the castle was not going to fall to an assault. The Takeda had also suffered an unexpectedly high proportion of casualties, but as the provisions store of the castle was now gone, Katsuyori estimated that the defenders only had a few days supplies left. He therefore decided to starve the garrison out. The attack was suspended, and while sniper fire and the occasional bombardment continued, a strong fence was begun which would totally surround the castle. It ran along the approximate line of the former outer defence works. For good measure, ropes were strung across the three rivers, with nets hanging down into the water, ‘so that even an ant could not get out’. Clappers were attached to the ropes to provide warning of anyone entering or leaving by that route.

The blockade began on 22 June and the garrison began to adjust to these new conditions of warfare. A 22-year old samurai-taishô (commander of a samurai unit) called Imaizumi Naiki stuck his head out of an arrow port to judge the progress of the siege and was seriously wounded by a sniper. He later died. In another sniper incident a certain Gotô Sukeza’emon was hit by a bullet, collapsed into a coma and never regained consciousness. Apart from these casualties, a sad loss to the garrison was the death from illness of the veteran warrior Shidara Shigetsugu, aged 79. He had served Tokugawa Ieyasu’s father, and his experience of warfare had proved invaluable.

All that the Takeda now needed was time. Six years later, at Tottori castle, a garrison would be almost reduced to cannibalism before their siege was over. Should no relieving force arrive, and none was apparently on the way, Nagashino castle would probably suffer the same fate within a week.

At this point in the siege there occurred one of the most celebrated incidents of samurai heroism in Japanese history. Torii Sune’emon was a 34-year-old samurai of Mikawa province and a retainer of Okudaira Sadamasa. His bravery was renowned and he was also very familiar with the territory, so he volunteered for the suicidal task of escaping from the castle and making his way to Okazaki to request help from Tokugawa Ieyasu.

A request had in fact already been sent before the blockade began, but no reply had been received, so the defenders were unaware that both Tokugawa Ieyasu and Oda Nobunaga had decided that the siege of Nagashino was a matter to be taken seriously and were planning to march to its relief. Oda Nobunaga had left Gifu on 20 June, travelled via Atsuta and arrived at Okazaki to join Ieyasu the following day. There was undoubtedly an element of self-interest in Nobunaga’s decision to throw the whole weight of his army behind an attempt to relieve a fortress of an ally when his own territories were not immediately threatened. However, Nobunaga was shrewd enough to realise that if he did not support the Tokugawa they might be swayed towards an alliance with the Takeda against him. So the force was committed unconditionally, and the outcome also promised a showdown with Takeda Katsuyori, which was itself a welcome opportunity. Yet clearly neither appreciated the extreme urgency of the situation, which made Torii Sune’emon’s mission all the more important.

Torii Sune’emon has daringly escaped from the castle, swimming the river and walking to Okazaki to tell them that relief is urgently needed. With his generals and allies beside him, Oda Nobunaga receives him in the audience hall. His suit of armour is on a stand in the corner. The room is lit by oil lamps on stands. Torii is still somewhat dishevelled, in contrast to the senior samurai who sit in full regalia, wearing jinbaori with their helmets beside them. The urgency of his mission is illustrated by the remarkable fact that he has been allowed in without removing his sandals. Nobunaga’s suit of armour is one that he is known to have worn.

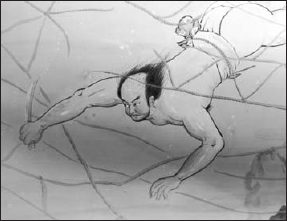

Torii Sune’emon swims under water. This modern painting in the Nagashino Castle Preservation Hall shows Torii Sune’emon cutting through the nets in the river with his dagger. From here he proceeded to Okazaki castle with the news that the garrison were near to collapse.

At midnight on 23 June Torii Sune’emon left the castle through the Yagyû-mon, climbed down the cliff path and slipped into the river. He swam down the Toyokawa until he reached the nets which the Takeda had strung across it. He cut a hole in the net under the water without making a sound, swam through and continued on his way. At dawn on 24 June he lit a beacon on Mount Gambo as a pre-arranged signal to inform the garrison that he had managed to get through. Then he carried on to Okazaki where he was warmly welcomed and admired for his feat. Torii Sune’emon reported that the castle had by then only about three days supply of food left, and that when that had gone all that Okudaira Sadamasa could do was to offer to commit hara-kiri to save the lives of his men. The castle would inevitably fall. Oda and Tokugawa promised to move the next day.

Torii Sune’emon is caught by the ropes. Suspecting that someone had escaped from the beleagured castle the Takeda stretched ropes across the river with bells attached to them. Their ringing gave Torii Sune’emon away to the watching sentries, and he was captured.

An old print (damaged by damp) showing Torii being forced to shout to the defenders of Nagashino across the Takigawa. There is considerable artistic licence in this picture. The castle of Nagashino, in reality no more than a large stockade reinforced with stone, has become a mighty fortress like Osaka castle, with a huge moat.

Torii Sune’emon then began the hazardous journey back to the castle to let Okudaira know that help was on its way and that he only needed to hold out for just that little bit longer. Again, as pre-arranged, Torii Sune’emon lit three beacons to inform the garrison of the good news, but instead of waiting for the relieving force to come along behind him, Torii Sune’emon attempted to re-enter the castle by the way he had departed. Unfortunately the Takeda had seen the beacons and concluded that someone from the castle had escaped, so this time they were ready for him. They spread sand on the river bank to disclose footprints and rigged up bells on ropes across the river where there had been none before. Torii Sune’emon was caught and brought before Takeda Katsuyori.

Throughout Japanese history examples of samurai bravery have been celebrated by friend and foe alike, and Torii Sune’emon’s exploit was no exception. Katsuyori listened to his story, including the intelligence that a relieving force was on its way, and offered the captive Torii Sune’emon service in the Takeda army. Torii Sune’emon apparently agreed, but the suspicious Katsuyori insisted that he demonstrate this change of allegiance by addressing the garrison and telling them that no army was on its way and that surrender was the only course of action. The spot chosen for Torii Sune’emon’s address was the place where the two lines were at their closest – the riverbank of the Takigawa at Shinobano. Some accounts say he was tied to a cross, others that he merely stood on the cliff edge to bellow out his message, but it was by crucifixion that he met his end. Instead of urging the defenders to surrender, he shouted to them to stand fast as help was indeed on its way. One account speaks of spears being thrust into his body as he uttered these words, others of his execution later.

However or whenever he died, the example of Torii Sune’emon is one of the classic stories of samurai heroism. Many in the Takeda army were moved by his example. One retainer of the Takeda, Ochiai Michihisa, was so impressed that he had a flag painted with an image of Torii Sune’emon tied to the cross, his body covered in blood. When Takeda Katsuyori was finally defeated in 1582 Ochiai became a retainer of Tokugawa Ieyasu, and the flag, which he used as his personal banner, still exists.

A detail from the damaged print shows one of the Takeda commanders, Anayama Baisetsu Nobukimi, ordering the control of Torii Sune’emon. Anayama is identified by the mon on his blue banner. He is attended by two footsoldiers who wear unusual jingasa with very pronounced conical shapes.

Torii Sune’emon is brought to the bank of the Takigawa in this lively modern interpretation on display in the Preservation Hall of Nagashino Castle. On the whole the details are fairly good, but again the castle is made impossibly ornate and large, and includes a drawbridge. The artist also does not seem to know what an ashigaru’s jingasa actually looked like.

One retainer of the Takeda, a certain Ochiai Michihisa, was so impressed by Torii Sune’emon’s bravery that he had a banner painted depicting the hero of Nagashino. This copy of the banner depicting Torii is being flown in the courtyard of the Nagashino castle site in preparation for the annual festival in May.

Whatever the effect Torii Sune’emon’s bravery had on the enemy, its effect on the garrison was inspiring. A relieving force was on its way and they only had to hold out for perhaps two more days.