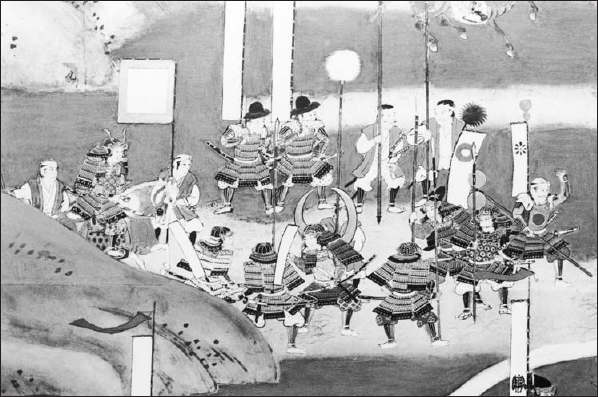

Now that he knew a relieving force was on its way Takeda Katsuyori held council with his senior officers, and received considerable differences of opinion over what to do. Shingen’s veterans, such as Baba Nobuharu, Naitô Masatoyo, Yamagata Masakage and Oyamada Nobushige, were for making an honourable withdrawal to Kai province. The younger ones were for fighting. Men like Atobe Katsusuke scorned the advice of their elders and called it a disgrace that the ever-victorious Takeda army should even consider withdrawing.

Katsuyori was inclined to agree with the younger ones. He no doubt thought that his honour was at stake. He had left Tsutsuji-ga-saki under the great blue banner with half the Takeda army and had first been forced to cancel the attack on Okazaki and then abandon the attack on Yoshida. Now he had failed to reduce a garrison that was outnumbered by 30 to one. The campaign had lasted nearly a month, and all Katsuyori had achieved was the burning of two minor satellite fortresses. To a samurai general, particularly one living under the shadow of a great father, the failure of the 1575 Mikawa raid would be an unbearable disgrace. The fact that his most senior officers were advocating such a course of action may well have served to make the potential loss of face that much keener for Katsuyori. To add to the failure of the siege by running from the two armies whom his father had defeated only three years earlier would have turned the knife further in the wound. To Katsuyori, obsessed to the point of irrationality by samurai honour and a need to emulate his father, even defeat by Oda Nobunaga might be preferable to running away from him. For the second time in the campaign the memory of Mikata-ga-hara played a crucial role in a military decision. Why should he, Katsuyori, not emulate Shingen by defeating the same enemies in battle?

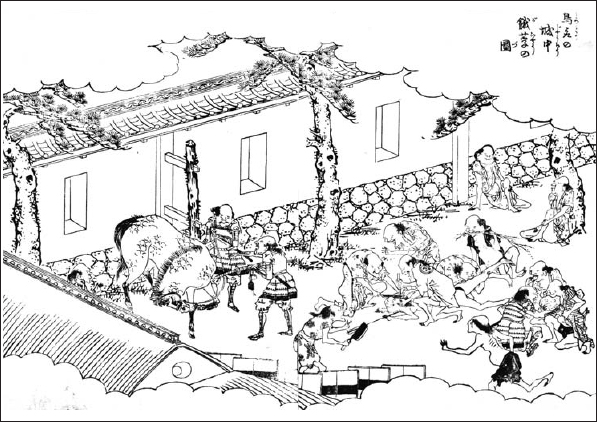

Starvation during the siege of Tottori. The most horrific siege in samurai history was the one conducted by Toyotomi Hideyoshi against the castle of Tottori in 1581. The defenders were eventually reduced to cannibalism in order to survive. This was the fate that Takeda Katsuyori had in store for the defenders of Nagashino. Note the detail of the interior of a castle’s walls.

The confluence of the rivers Takigawa and Onogawa as seen from the water level. Above soars the cliff on which Nagashino castle was built. To the right lies the site of the Yagyû-mon, the water-gate, out of which Torii Sune’emon escaped to bring help. The river was much higher during the siege, as we know that the attackers were able to float a raft down it. This would be impossible nowadays.

There were several very good reasons why that was unlikely to happen. For the Takeda the situation at Nagashino was Mikata-ga-hara in reverse. At Mikata-ga-hara Takeda Shingen had enticed a Tokugawa army of 11,000 out of Hamamatsu castle to attack his massive 25,000-man force. The events of the previous week had shown that Tokugawa Ieyasu had learned his lesson and was not to be enticed out of Yoshida. Instead, Oda Nobunaga with his 38,000 now seemed to be enticing the Takeda with their 15,000 from their secure siege lines. It was an uncomfortable parallel for the veterans of 1572, but soon even the old generals had to accept that Katsuyori was determined to meet Nobunaga in battle, and their techniques of persuasion changed from urging a tactical withdrawal to meeting Oda Nobunaga on ground of their own choosing.

Baba Nobuharu suggested that if there was to be a fight it should be conducted from within Nagashino castle. The Takeda should therefore make a determined effort to take the fortress before the allied army arrived. He reasoned that since the matchlockmen would only be able to get in two shots apiece before the Takeda samurai reached the walls, no more than a thousand casualties could be expected before a hand-to-hand fight started, and in this the Takeda would certainly prove victorious through sheer weight of numbers. They could then face the Oda and Tokugawa from within the walls, with the Takigawa acting as a forward moat.

In this plate the allied Oda/Tokugawa army take a brief rest on their way to the relief of Nagashino. On the left we see one of Tokugawa Ieyasu’s elite mounted messengers (identifiable by the character ‘go’ on his sashimono) who is engaged in conversation with Sakakibara Yasumasa. Yasumasa has seated himself on a tree stump and, even in this relaxed and comparatively safe position, a personal attendant stands immediately behind him, while an ashigaru bodyguard flanks him with a spear. Shielding his eyes from the sun is Sakai Tadatsugu, another Tokugawa retainer, whose sashimono flag bears a depiction of a death’s head. Behind them the Tokugawa army marches on. We see the great golden standard, and the flag presented to Tokugawa Ieyasu by the Jodo monks of Okazaki, and many nobori banners bearing Tokugawa mon. The red suns on white are Sakai troops. Details of the two general’s suits of armour are taken from actual examples preserved in Japan which they are believed to have worn at about this time. Sakai’s death’s head flag is on display in the new museum devoted to the battle of Nagashino in Shinshiro, immediately adjacent to the battlefield.

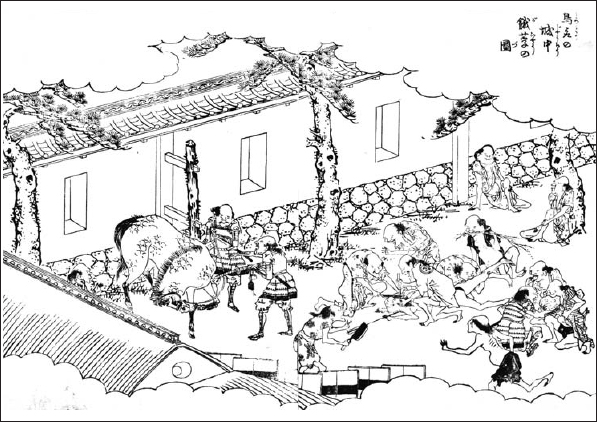

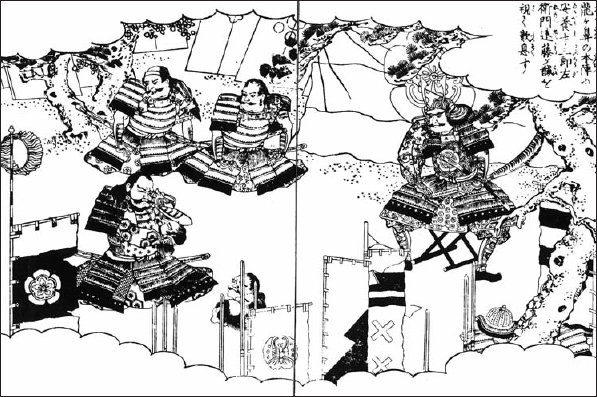

The night before the battle Takeda Katsuyori held a council of war with his generals, at which the fateful decision was made to attack the relieving force brought to Nagashino by Oda Nobunaga. This painted scroll in the Nagashino Castle Preservation Hall depicts that historic moment. Katsuyori sits at the top left, while his generals express emotion at their coming doom.

However, this view did not prevail. It was Katsuyori’s final decision that the Takeda would meet the relieving army in a pitched battle the following morning. The old generals had followed Shingen loyally and had transferred that loyalty to his son. Unlike Katsuyori, they realised that to fight Nobunaga with such a disadvantage of numbers and ground was almost suicidal, but their duty now meant that they must die with him. Four of the old Twenty-Four Generals – Baba Nobuharu, Naitô Masatoyo, Yamagata Masakage and Tsuchiya Masatsugu – exchanged a symbolic farewell cup of water together and prepared to take on the tremendous odds.

The site of the inner bailey of Nagashino castle is highlighted in this telephoto shot. The Takigawa river is very prominent. By the fourth day of the siege this tiny area was all that remained under the control of Okudaira Sadamasa. Everything else had fallen to the Takeda assault.

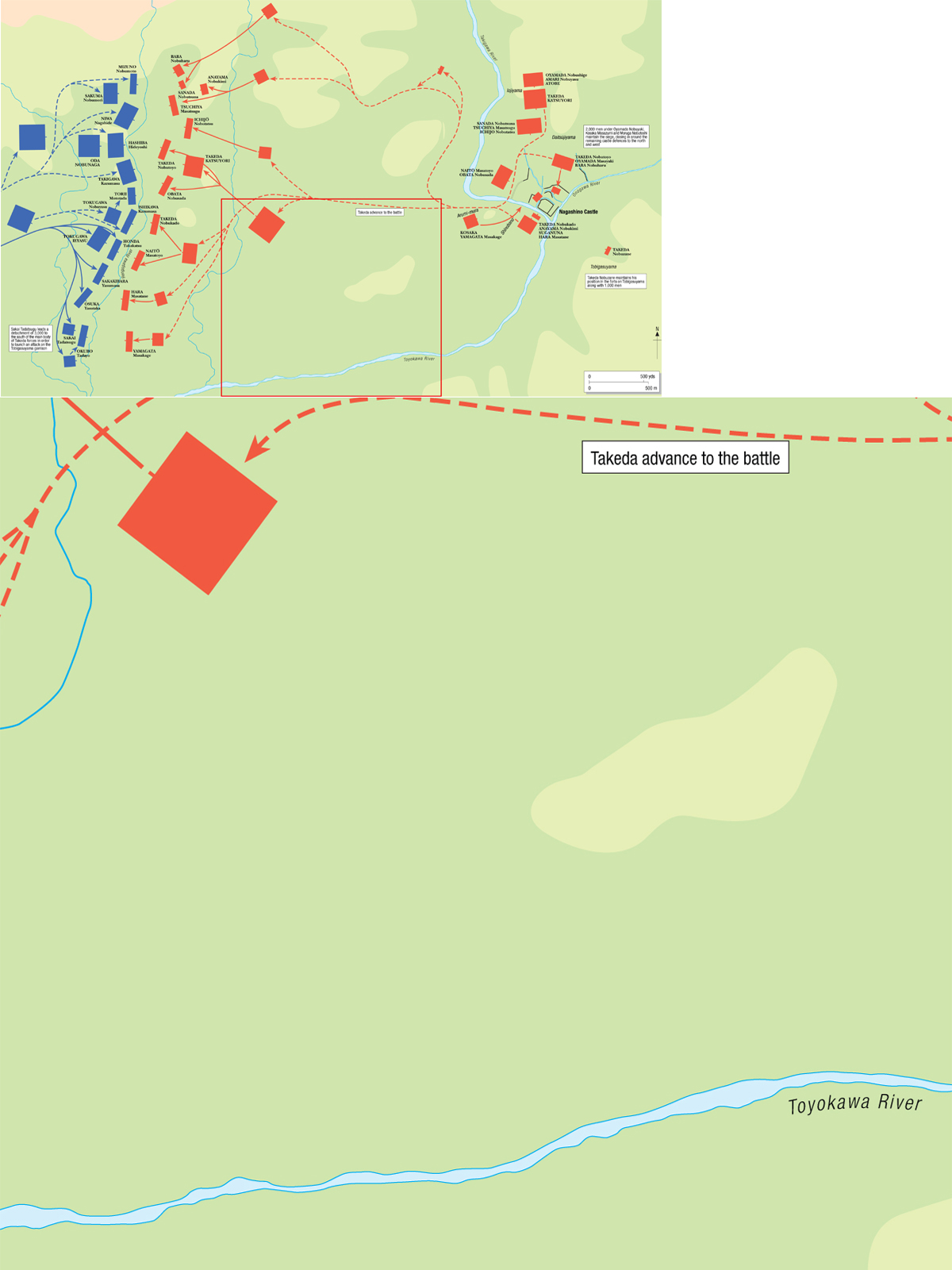

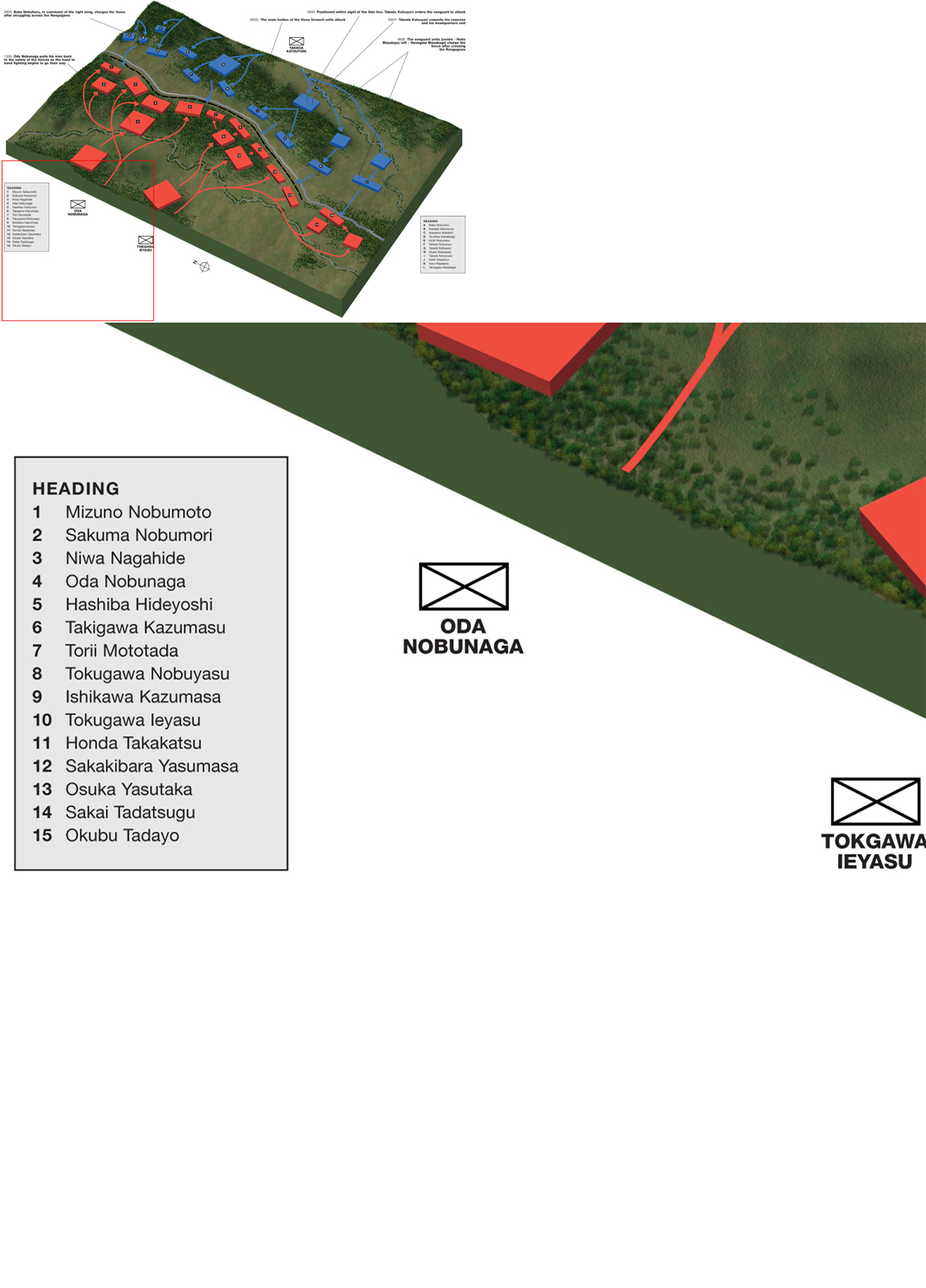

As they had promised to Torii Sune’emon, Oda Nobunaga and Tokugawa Ieyasu left Okazaki castle at the head of a force of some 38,000 men on 25 June. The day after their departure the Oda-Tokugawa army reached Noda castle, and left again early the following morning, 27 June. Towards evening they were five or six km west of Nagashino on the plain of Shidarahara. Here Oda Nobunaga selected his positions. It was sufficiently far from the castle to enable him to arrange his forces without immediate interruption. According to contemporary descriptions, Oda Nobunaga dressed in style, wearing a fine yoroi armour. One of his attendants carried his helmet, an elaborate affair rather like a sombrero in shape. Other servants carried his weapons and three white banners on which were designs of a Japanese coin. To the rear was kept the packhorse supply unit, while the fighting men were arranged in a formation that made best use of the ground and took into account the Takeda’s prowess with cavalry.

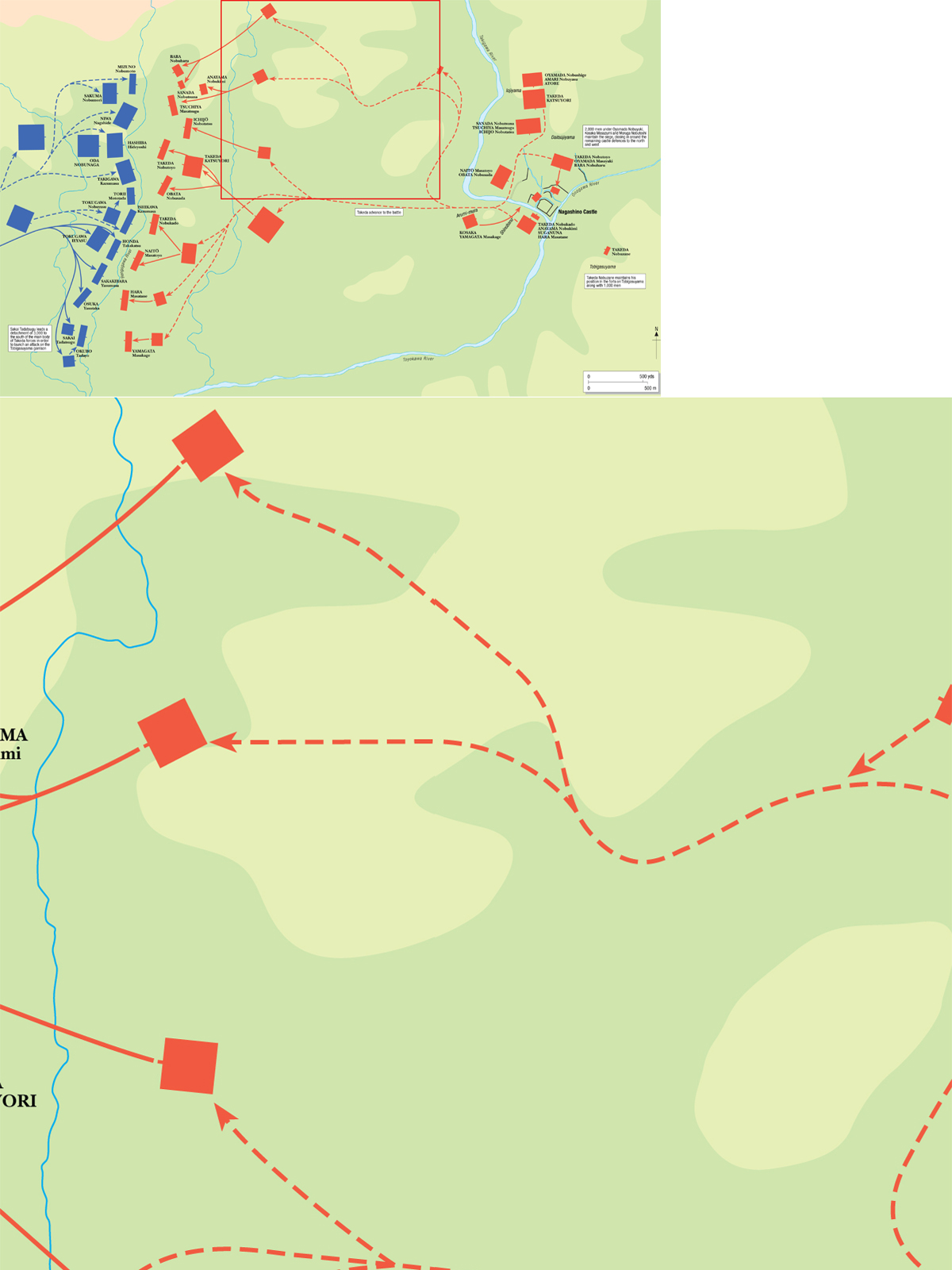

The initial positions adopted on arrival allowed Nobunaga to secure the nearby hills, with the left flank protected by forested mountains and the right by the Toyokawa. Oda Nobunaga’s headquarters were set on Gokurakujiyama, to the rear. To the north, on Nobunaga’s left, was Kitabatake Nobuo on Midoyama. Forward of him, on Tenjinyama, was Oda Nobutada. Further contingents of the Oda army moved forward to occupy other hills. Sakuma Nobumori, Ikeda Nobuteru, Niwa Nagahide and Takigawa Kazumasu based themselves on Chayasuriyama, and the others clustered around it. Two Tokugawa contingents – Tokugawa Nobuyasu and Ishikawa Kazumasa, commander of the western Mikawa force – held Matsuoyama, slightly in advance of the Oda main body. The rest of the Tokugawa force spread out along the next set of hills, closer to the Takeda siege lines. Tokugawa Ieyasu made his overnight base on Danjôyama, along with Okubo Tadayo, Honda Tadakatsu, Sakakibara Yasumasa, Hiraiwa Chikayoshi, Sakai Tadatsugu, Torii Mototada, Naito Ienaga and the others. The Tokugawa army totalled 8,000 men.

It is quite clear that the Oda-Tokugawa dispositions were almost totally controlled by fear of the Takeda cavalry. Both the allied commanders had suffered its effects at Mikata-ga-hara, so once again the experience of that battle was to play a vital part. One effect was the selection of ground. The Oda-Tokugawa positions looked across the plain of Shidarahara towards the castle, which could not be seen because of further hills in the way, but it was no flat plain like Mikata-ga-hara. About 100m in front of them flowed the little Rengogawa, which acted as a forward defence for the positions Oda Nobunaga had chosen. Although sluggish and shallow, it had some steep banks, which would slow down the horsemen.

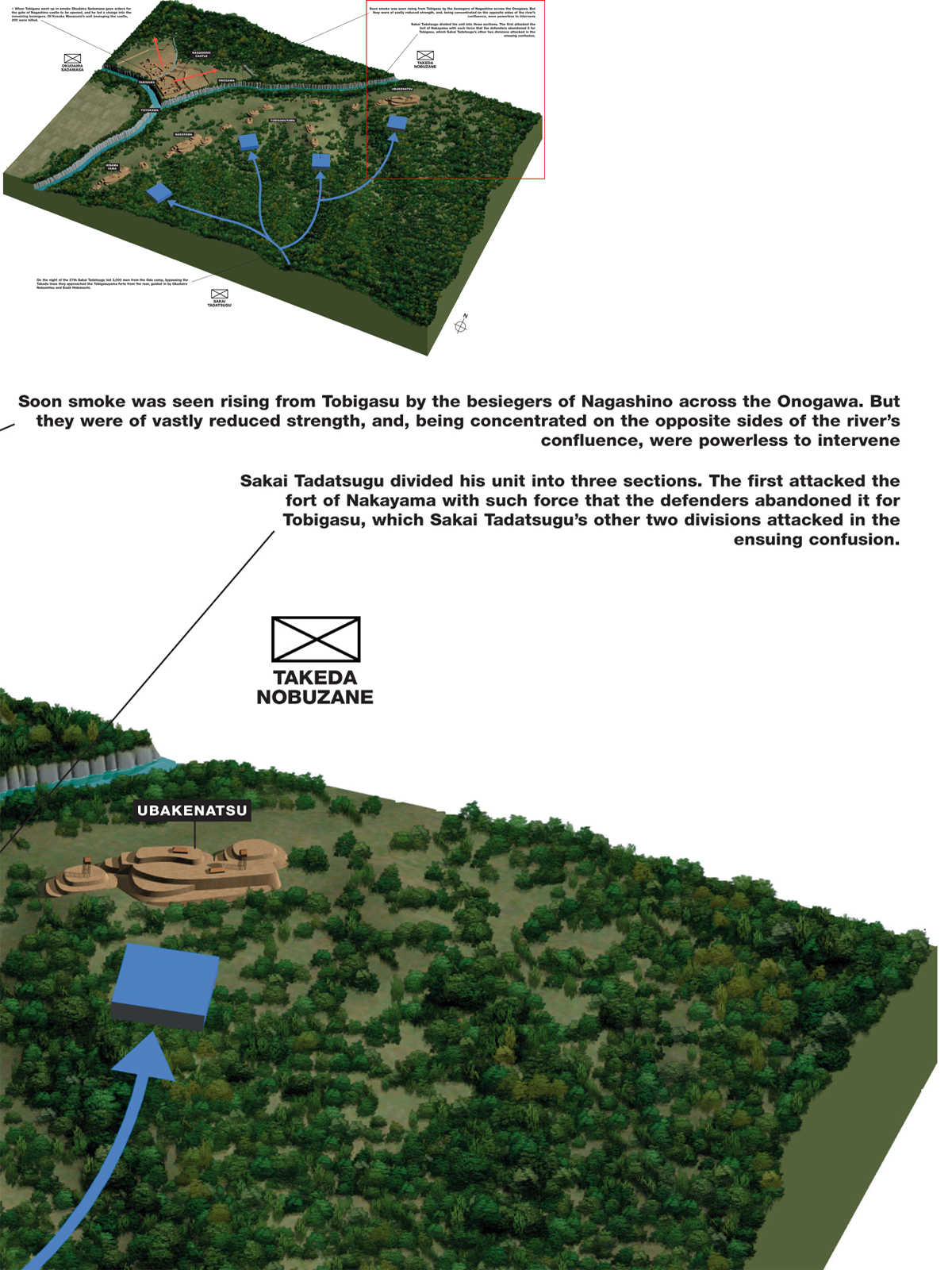

The hill of Tobigasu, looking up from the site of Nagashino castle across the Onogawa. This was the location of the dawn raid by Sakai Tadatsugu against the camp of Takeda Nobuzane. The terraced fields still follow the outlines of the field fortifications prepared by the Takeda for the siege of Nagashino.

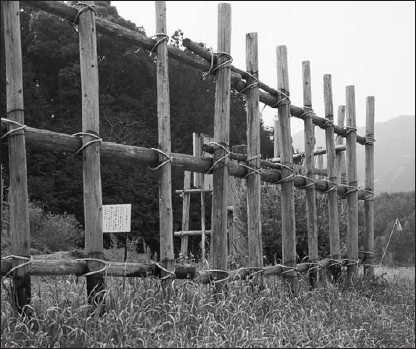

Oda Nobunaga also clearly appreciated the need to give his matchlockmen some form of physical protection, so the Oda army had brought with it a large quantity of cut timber with which to build a palisade. Half way between the forested edge of the hill and the river Oda Nobunaga’s troops erected this loose triple fence of stakes, stretching from the point where today the Rengogawa is crossed by a bridge to the north, where Ikeda Nobuteru was positioned. It was not a continuous construction, but was staggered over three alternate layers, with many gaps to allow for counter-attack. It also stopped short of the Toyokawa, because here, on the right flank, there was not the same cover to the rear that the hills provided for the rest of its length. The forests of the left flank provided some protection from encirclement, and Nobunaga must have decided to risk his right wing rather than weakening the whole line by spreading his defences too thinly.

Behind the fence the matchlockmen would be stationed, giving them a good range over the Rengogawa and the attacking cavalry. The total front of the Oda-Tokugawa army stretched for about 2,100m.

That night Takeda Katsuyori made the final decision to give battle to the relieving force. Plans were drawn up for who should lead the attack and who should remain at Nagashino to continue the siege. The battle arrangement was to be four divisions – right, centre and left, with a headquarters unit to the rear. The four divisions would total 12,000 men leaving 3,000 to continue the siege. Of these, 2,000 under Oyamada Nobuyuki, Kôsaka Masazumi and Muroga Nobutoshi closed in on the west and north sides of the remaining castle defences. Across the Onogawa, Takeda Nobuzane kept up his lonely vigil from the hill of Tobigasu with the remaining 1,000 men.

While Katsuyori deliberated, a similar council of war was taking place in the Oda headquarters. As Oda Nobunaga sat with his generals he was approached by Sakai Tadatsugu of the Tokugawa force, who suggested launching a surprise attack against the Takeda siege lines as the Takeda army advanced. Sakai Tadatsugu had successfully carried out a similar manoeuvre at Mikata-ga-hara in 1572. Nobunaga did not appear to be at all enthusiastic about the plan, and upbraided Sakai Tadatsugu for his presumption in speaking out of turn, the latter retired somewhat hurt. However, Nobunaga interviewed him in private later, and assured him that he supported his plan. His anger had merely been a camouflage to throw any spies off the scent. To launch a rear attack simultaneously, with the Takeda advance away from the security of their siege lines, would be a tremendous psychological advantage. As proof of his support Nobunaga gave Sakai Tadatsugu a detachment of 500 matchlockmen under the command of Kanamori Nagachika of the elite aka horô-shû. This gesture clearly shows how confident Nobunaga was of stopping the Takeda cavalry the following day.

The raiding party was 3,000 strong. Sakai Tadatsugu was in overall command, assisted by Matsudaira Ietada, Matsudaira Tadatsugu, Honda Hirotaka, Honda Yasushige, Makino Narimune, Okudaira Tadayoshi, Suganuma Sadamitsu, Nishikyô Iekazu, Shidara Sadamichi and Abe Tadamasa, while Okudaira Nobumitsu and Endô Hidemochi acted as guides.

The northern slope of Tobigasu, looking down towards the castle.

The defence line of the Oda/Tokugawa army was not protected by a continuous fence, but one that was staggered to allow a counter attack. Here one of the gaps has provided a natural lure for one detachment of Takeda cavalry under the command of Obata Masamori (also called Nobusada). The famous volleys of gunfire have done their worst, but several hours of fierce hand to hand fighting are still in prospect, and a particularly fierce encounter is about to begin. Taking advantage of a brief lull in the gunfire Obata’s troops charge full tilt at the gap in the fence. Defending the line are the troops of Torii Mototada, one of the finest of the Tokugawa samurai. As the gunners pull back to regroup the footsoldiers with their long spears come into their own.

In this fine print, which is one of Yoshitoshi’s famous series ‘One hundred aspects of the moon’ Sakai Tadatsugu leads the raid on Tobigasu which coincided with the battle of Nagashino. Yoshitoshi has given Sakai Tadatsugu a sashimono in the form of a three-dimensional death’s head, made of wood.

The Sakai force left at midnight under the cover of a heavy rainstorm. Being guided by local men who were familiar with the territory even in darkness, the army covered the 8km safely. They swung widely to the south, bypassing the Takeda lines and approaching the Tobigasuyama forts from the rear. There they waited patiently for the morning.

As dawn broke over Shidarahara, Oda Nobunaga made his final dispositions. Retaining his command post to the rear on Gokurakujiyama, he placed his eldest son, Nobutada, in charge of the rearguard and moved himself up to the prepared positions behind the fence. The palisade had been completed overnight, and in the morning it was inspected by Ishikawa Kazumasa and Torii Mototada to ensure that it would not allow an enemy horse to jump over it.

Behind the 2,000m palisade Nobunaga placed his remaining 3,000 matchlockmen. The gunners, arranged three ranks deep, were under the command of members of Nobunaga’s horô-shû, his finest samurai. Their normal duties were to act as his personal bodyguard, and for Nobunaga to use them to command lower class missile troops shows the immense importance Nobunaga attached to the role of the ashigaru gunners. It also shows that Nobunaga appreciated that firm discipline would be crucial. His plan was for the matchlockmen to fire rotating volleys as the Takeda cavalry approached, and for this to succeed the seven men of the horô-shû would have to exercise complete control. The matchlockmen had kept their weapons and their fuses dry during the rain – a lesson Nobunaga had learned the hard way from the Ikkô-ikki at Nagashima in 1573.

An aerial view of the immediate area of Nagashino castle. The ‘Y’ shape of the river is clearly shown. Torii Sune’emon was crucified next to the location of the present railway bridge. The attack on Tobigasu took place from the wooded hills in the bottom right hand corner on to the forest to the north of the hill.

Shibata Katsuie, one of Nobunaga’s generals, as seen in his statue in Fukui.

The Oda-Tokugawa line now stood as follows. On the extreme right wing, where clumps of trees led down to the Toyokawa, was Okubo Tadayo. He was 44 years old and had served in all Ieyasu’s campaigns. His black and white standard had been seen next to Ieyasu’s own at the battle of the Anegawa. His was the only position at Nagashino not covered by the fence. To some extent he was protected by trees, but the ground was flat, and his 1,000-strong contingent had been given a ‘roving commission’ to deal with any attempted encircling movement. Here he would receive the charge of one of the Takeda’s finest cavalry commanders, Yamagata Masakage.

Oda Nobunaga sits in camp. In this page from the Ehon Taikô-ki Oda Nobunaga is shown with his mon on the breastplate of his armour. The insignia of several of his generals appear on the flags, including the butterfly of Ikeda and the crosses of Niwa.

Next to Okubo, and protected by the end of the fence, was Osuka Yasutaka and Sakakibara Yasumasa, aged 27 and another faithful Tokugawa fudai. Each commanded 1,000 men. Along with Sakai Tadatsugu, Honda Tadakatsu and Ii Naomasa (who was not present at Nagashino) he was reckoned to be one of Ieyasu’s shitennô – his four most loyal followers. Honda Tadakatsu was next along the line with a further 1,000 troops, and was instantly recognisable by the antlers on his helmet. He had the honour of having Tokugawa Ieyasu immediately behind him in the battle with his 2,000 men. Here flew the golden fan standard of the Tokugawa, and 20 white banners bearing the Tokugawa mon (badge). Almost in the centre of the line were Ishikawa Kazumasa with 1,000 and Torii Mototada with 800, both trusted retainers of the Tokugawa. Ieyasu’s son Tokugawa Nobuyasu, then aged 16 and getting his first taste of battle, formed the second rank behind them, with 1,000 men. They were to face the charge from Takeda Katsuyori’s centre corps, under Naitô Masatoyo.

Next to Torii stood the first of Nobunaga’s contingents in the person of Takigawa Kazumasu. Next to him was Nobunaga’s greatest general of all: Hashiba Hideyoshi, later to be known as Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the ‘Napoleon of Japan’. As guard unit he had the honour of having Oda Nobunaga’s personal contingent immediately behind him. Niwa Nagahide was next along, and the line was concluded behind the fence by Mizuno Nobumoto, supported to the rear by Sakuma Nobumori.

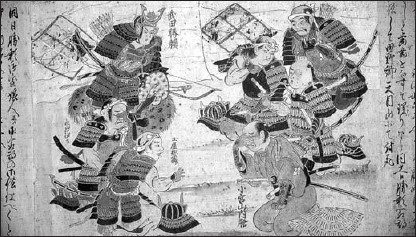

In this section from a painted screen depicting the battle of the Anegawa in 1570 we see two prominent characters who fought on the Oda side at Nagashino five years later. Tokugawa Ieyasu sits in command beside the two flags proclaiming the motto of the Jôdo sect of Buddhism – ‘Renounce this polluted world and attain the Pure Land’. The black flag indicates the presence of Okubo Tadayo, who commanded the vulnerable right wing at Nagashino, where there was no fence for protection. His troops met the onslaught of the veteran general Yamagata Masakage.

As noted above, each of the four Takeda divisions consisted of about 3,000 men. Using the figures from the Kôyô Gunkan, it is possible to be quite precise about the composition of the four contingents. In the tables which follow, the number of mounted troops is given, to which are added a small number for the named individuals (there were more than one present from certain families) and their attendants at two each. The analysis reveals that the forward three divisions were almost completely cavalry units, the only foot present being the personal attendants of the horsemen.

The right wing was under the overall command of Anayama Nobukimi. He was one of Shingen’s veterans and a member of the goshinrui-shû. As a result, his samurai and ashigaru wore the Takeda mon on their flags, while his personal banner retained its own mon. Baba Nobuharu led the vanguard with 120 mounted samurai. He was a fudai and one of the Takeda’s most experienced field commanders. The brothers Sanada Nobutsuna and Sanada Masateru followed. They were of the sakikatashû, the families taken on by the Takeda after conquest. The Sanada family, from Shinano province, had long proved their loyalty and worth to the Takeda. Tsuchiya Masatsugu and Ichijô Nobutatsu completed the right wing. The former had fought at Mikata-ga-hara with great distinction. The latter was in the goshinrui-shû and was a cousin of Takeda Katsuyori. He commanded 200 horsemen. The right wing was directed against the extreme left wing of the Oda army, under Hashiba and Sakuma.

| RIGHT WING | |

| Anayama Nobukimi (commander) | 200 |

| Baba Nobuharu (vanguard) | 120 |

| Sanada Nobutsuna and Sanada Masateru | 250 |

| Tsuchiya Masatsugu | 100 |

| Ichijô Nobutatsu | 200 |

| Tokita Tosho | 10 |

| Imogawa Ennosuke | 60 |

| Unnamed samurai from the Shinano sakikata-shû | 60 |

| Other named individuals | 12 |

| Unmounted attendants to the above | 2,024 |

| Total | 3,036 |

The centre companies were to be about 3,000 men under the overall command of Takeda Nobukado, Katsuyori’s uncle, whose men, including 80 horsemen, wore a white Takeda mon on black flags. He attacked the section of fence defended by Ishikawa Kazumasa. The vanguard was led by Naitô Masatoyo, who charged home against Honda Tadakatsu. They were supported by the veteran fudai Hara Masatane, who was particularly prized for his feel for ground in strategic planning. The western Kôzuke sakikata-shû supplied Wada Narimori, Annaka Kageshige and Gomi Takashige plus unnamed units of 14 horsemen. Within the centre company was the largest single contingent of horsemen in the Takeda army. This was a 500-strong unit under Obata Nobusada, also of the western Kôzuke sakikata-shû.

| CENTRE COMPANY | |

| Takeda Nobukado (commander) | 80 |

| Naitô Masatoyo (vanguard) | 250 |

| Hara Masatane | 120 |

| Obata Nobusada | 500 |

| Annaka Kageshige | 150 |

| Wada Narimori | 30 |

| Western Kôzuke (unnamed) | 14 |

| Other named individuals | 9 |

| Unmounted attendants to the above | 2306 |

| Total | 3459 |

The left wing was a further 3,000 men under the overall command of Takeda Nobutoyo, a cousin of Katsuyori. He was the son of the great Takeda Nobushige, who had been killed at Kawanakajima in 1561. He rode under his late father’s personal banner of a white disc on black. The vanguard of the left wing was in the most experienced hands of all. Yamagata Masakage was 60 years old and, following the example of his late brother, dressed all his troops, 300 of whom were mounted, in red armour. His flag was a white flower on black. The balance of the 3,000 included the names of individual samurai, with varying numbers of followers. Among them were Ogasawara Nobumine, Matsuoka Ukyô (Shinano sakikata-shû), Suganuma Sadanao (Mikawa/Tôtômi sakikata-shû), the veteran Oyamada Nobushige, the young Atobe Katsusuke and the fudai Amari Nobuyasu.

| LEFT WING | |

| Takeda Nobutoyo (commander) | 200 |

| Yamagata Masakage (vanguard) | 300 |

| Nagasaka Jûza’emon | 40 |

| Atobe Katsusuke | 300 |

| Amari Nobuyasu | 100 |

| Oyamada Nobushige | 200 |

| Suganuma Sadanao | 40 |

| Matsuoka Ukyô | 50 |

| Other named individuals | 12 |

| Attendants to the above | 2,484 |

| Total | 3,726 |

The centre company to the rear, which was Takeda Katsuyori’s headquarters unit, set up a base within a maku (field curtain) on the hill overlooking Shidarahara. From here Takeda Katsuyori could control the operation and would be in a position to join in the fighting later if necessary. The unit was composed of a number of Takeda Katsuyori’s closest and youngest relatives on the field, drawn from the goshinrui-shû as samurai hatamoto. They were led by Takeda Katsuyori himself, along with Takeda Nobutomo – Katsuyori’s cousin, Takeda Nobumitsu – a son of the late Shingen, aged 22 and therefore Katsuyori’s uncle, and Mochizuki Nobumasa – another cousin in the shinrui-shû who was the younger brother of Takeda Nobutoyo, aged 25. The balance of the division was made up from the hatamoto ashigaru. This contingent was again 3,000 strong, and was to advance to the attack through the Kiyoida area, directly across from the castle to the fence. They eventually went into the charge opposite Oda Nobunaga’s headquarters unit.

| TAKEDA HEADQUARTERS UNIT | |

| Takeda Katsuyori (commander) | 200 |

| Takeda Nobutomo (individual) | 0 |

| Takeda Nobumitsu | 100 |

| Mochizuki Nobumasa | 60 |

| Other named individuals | 4 |

| plus attendants to the above | 728 |

| Total | 1,092 |

This is a much smaller number than the approximate figure of 3,000 given in the chronicles. However, the contingent from the Suruga sakikata-shu (239 horsemen) and the ashigaru-taisho (98 horsemen) are not allocated to a position in the records, so they may have formed part of the headquarters unit. There would also have been a considerable number of ashigaru. In addition, 360 horsemen remained behind in the siege lines. The overall formation chosen by the Takeda, with three forward divisions and one supporting them, was known by the poetic name of kakuyoku (crane’s wing) from the shape of a crane’s wings in flight.

For the majority of the Takeda troops their first sight of the enemy came only when they moved out of the woods to the east of Shidarahara. From this point it was 200m at the narrowest to the Oda-Tokugawa line, and at its broadest, where Ichijô Nobutatsu was stationed, only 400m. Although he was aware of the number of guns that Oda Nobunaga possessed, two factors encouraged Takeda Katsuyori. The first was the heavy rain of the previous night, which was likely to have rendered the matchlocks unusable. The second was the likely speed of the Takeda charge. A distance of 200m would allow the Takeda to move quickly into a gallop as soon as they left the wooded area. With only 200m to cover, he could expect some casualties from bullets, but not enough to break the momentum of the charge. The horsemen would then be upon the hopeless ashigaru as they tried to reload, followed within seconds by the Takeda footsoldiers. There would then be a hand-to-hand fight in which the Oda guns would be a useless encumbrance. The Takeda samurai would sweep the fence to one side and pursue the retreating enemy down to the Toyokawa, where the river would cut off their retreat.

Honda Tadakatsu was the loyal follower of Tokugawa Ieyasu, and the antlers on his helmet made him a prominent sight in the front ranks of the Oda/Tokugawa army at Nagashino. Much fierce fighting flowed around the section of the line commanded by Honda Tadakatsu. This statue of him is in the grounds of Okazaki castle.

At the time of Nagashino Toyotomi Hideyoshi was in command of one of the three elite units who made up Oda Nobunaga’s go umamawari-shû. He eventually succeeded Nobunaga as master of Japan when the latter was murdered, and became known to history as ‘The Napoleon of Japan’.

One hour passed before Takeda Katsuyori gave the order to move forward. Most accounts of the battle of Nagashino give the impression that there was then a sudden charge which was broken by the gunfire, followed by another and another, until within minutes the majority of the Takeda horsemen lay dead from bullet wounds, and the Oda samurai finished them off. This is certainly the picture conveyed by the film Kagemusha, which takes many historical liberties with the battle. In fact, Takeda Katsuyori’s order to advance set in motion no less than eight hours of bitter and bloody fighting. The matchlocks were decisive in producing the victory for Oda Nobunaga, but they were by no means the whole story. A good parallel is the battle of Agincourt, where the English longbows broke the French charge and created a situation which the English men at arms were able to exploit to their advantage.

Shibata Katsuie distinguished himself in every battle in which he took part. This print illustrates an incident during his defence of the castle of Chôkoji in 1570, when he smashed the water storage jars as earnest of his intentions to fight to the death. This so inspired the men under his command that they sallied out and carried all before them.

At 06.00 on 28 June 1575 Takeda Katsuyori ordered the advance which began the Battle of Nagashino. To the sound of the Takeda war drums carried on the backs of ashigaru, the three vanguards of the Takeda cavalry under Yamagata, Naitô and Baba swept down from the hills onto the narrow fields. The initial move created considerable momentum. No guns opened up on them because Nobunaga’s discipline was strict. The Takeda advance was then greatly slowed by the banks of the Rengogawa. Horses and men carefully negotiated the shallow river bed, picking up speed again as they mounted the far bank. At this point, with the horsemen within 50m of the fence, the volley firing began. As some gunfire had been expected the initial fall of men and horses did not cause Takeda Katsuyori any great concern. What shocked him was the rapid second volley, and then the third. All along the line his horsemen in the vanguards, and the attendant footsoldiers who had advanced with them, were falling in heaps as the fusillade tore into them from the calm Oda gunners under the iron hand of the men of the horôshû.

It is this moment of the battle that is the most prominent feature of the famous painted screen depicting the battle of Nagashino in the Tokugawa Art Museum in Nagoya. Several incidents at different times of the day are shown on various parts of the screen, but the most dramatic vignette is of the ranks of Takeda horsemen falling beneath the bullets of the Oda matchlockmen. Although several personalities have been transposed from the positions they are believed to have occupied, the screen provides a vivid illustration of the impact of the matchlock volley firing. It was the three vanguard units who felt the first blast of the matchlockmen, but before looking at any section in detail, it is worth considering what the impact of the charge would have been from the point of view of the matchlockmen and their comrades – and for the Takeda cavalry.

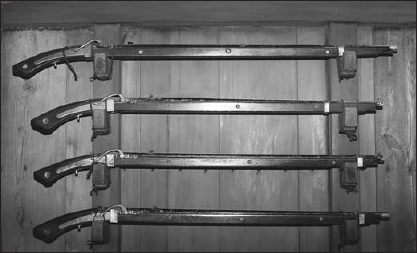

The arquebuses used at Nagashino had a maximum range of 500m, a distance at which even volley firing could be expected to do little damage. The maximum effective range for causing casualties was 200m, which was just a little less than the distance from the fence to the woods out of which the Takeda cavalry began their charge. It is highly unlikely that Nobunaga would have allowed any firing at this range, because the slight wounds caused would not have interrupted the flow of the charge and would have wasted at least one of the volleys. At 50m, the distance from the fence to the Rengogawa, the effects would be more pronounced. Modern experiments have shown that an iron plate of 1mm thickness could have been be pierced by an arquebus ball at this distance, and as the iron from which the samurai’s dô-maru armour was made was 0.8mm in thickness a hit from 50m range could have caused considerable damage. However, firing at 50 m was likely to be much less accurate than firing from 30m, because other modern experiments have shown that an experienced gunner could hit a man-sized target with five shots out of five at the shorter distance, compared with one in five at 50m. The first volley was therefore fired at a slow moving target, while the second was delivered at a potentially greater accuracy but at a moving target. The third volley must have been fired at almost point blank range.

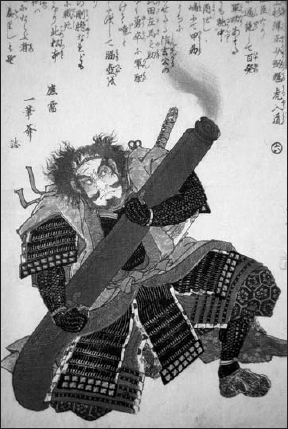

A rather elaborate print by Kuniyoshi depicting a samurai wielding a very large arquebus. The decisive weapons employed so successfully at Nagashino are likely to have been the smaller versions shown elsewhere in this book, with weapons like this one confined to use during the siege.

There remains the question of how many volleys were actually fired. In a third modern experiment an experienced Japanese arquebus enthusiast managed to perform the sequence of load, prime, aim and fire in as little as fifteen seconds, a speed comparable to that of a flintlock musket. Other studies of arquebuses have shown that the need to keep the smouldering match out of the way while the pan is primed slows the process down to a more realistic rate of between twenty and thirty seconds, or in clumsy and inexperienced hands no better than one shot every minute. There is also the factor of the fouling of a barrel after a number of shots have been fired. In the case of an eighteenth century French flintlock, for example, fouling reduced the firing rate from one shot every twelve seconds to one shot every 45 seconds. As Nobunaga is recorded as having chosen his ‘best shots’ the rate of fire may well have be on the high side.

As we cannot know precisely the rate of fire used at Nagashino it is more profitable to approach the problem from the viewpoint of the Nagashino topography. In the Nagashino situation the gunners were being charged by horsemen capable of moving at 40km an hour or 11 metres per second. If the Rengogawa had not been in the way they would have been travelling at an uninterrupted speed and would therefore have covered the final 50m, during which we may assume all the firing took place, in about five seconds. The Rengogawa, however, must have slowed them to a walk, and at certain places brought them to a temporary halt. But even doubling or even trebling the time needed still only allows ten or fifteen seconds for the Oda army to shoot at them. This being the case, it is irrelevant whether the rate of fire was one shot every fifteen seconds or one shot every 45 seconds. We must instead envisage the three ranks of arquebusiers, all of whom already had loaded weapons, delivering only one shot each in that brief amount of time when the horsemen bore down upon them. As there were 3,000 gunners it means that some 8,000 bullets (misfires must have occurred) were delivered in three controlled volleys. It is possible that the carnage and confusion inflicted on the Takeda by the first two volleys may have given just enough time for the first rank to reload and fire a second volley of their own, making it four volleys in all, but a more likely scenario is that the process of reloading began en masse after the initial firing, and that the three ranks did not fire again until the next wave of horsemen arrived at the Rengogawa. This is certainly indicated by the fact that the whole battle lasted eight hours. Nagashino was definitely not the ‘machine-gun’ battle that is erroneously implied by the film Kagemusha.

A rack of guns at Himeji castle. The arquebuses used at Nagashino would have been very similar in appearance to the guns shown here. One indirect effect of the battle of Nagashino was a concentration on means of defence, of which artillery in castles was but one illustration. The walkways round the interior of Himeji are furnished with racks for spears and guns.

The little river known as the Rengogawa played a decisive strategic role at the battle of Nagashino. Its flow has now been controlled, as this photograph illustrates, but the viewer is still given a strong impression of how its banks would have slowed down a cavalry charge.

As dawn broke over Shidarahara, Oda Nobunaga made his final dispositions and the four Takeda divisions began to advance against him.

The fence on Shidarahara as seen from the Rengogawa, about 50 metres away. This was the sight that would have met the eyes of the Takeda horsemen as they negotiated the Rengogawa and spurred their horses on up the slope towards the palisade.

So what happened to the arquebusiers after they had fired? In spite of all the noise, confusion and danger they would have had to give their total concentration to the business of reloading, ensuring that the touch hole was clear, that the bullet was correctly rammed down, and that there was no chance of the smouldering match causing a premature discharge. Here the presence of the fence and their ashigaru comrades with their 5.6m long spears would have provided the protection they needed in this Japanese version of a European ‘pike and shot’ unit.

It would also be a mistake to think of mounted samurai charging forwards and simply crashing into a line of infantry, whether or not they were protected by fences. The success of a cavalry charge depended on the footsoldiers breaking ranks, at which the horsmen could enter their midst and cut them down at will. This had happened in the European theatre of war in 1568 at the battle of Riberac. The point about Nobunaga’s tactics was that the arrangement of the guns, the fences and the spearmen allowed him to control the impact of the Takeda assault. As an English commentator put it in 1593, ‘the charge of horsemen against shot ... is mortall if they be not either garded with pikes, or have the vantage of ditches, or hedges, or woods, where they cannot reach them.’

No doubt the dismounted samurai of the Oda and Tokugawa would have been itching to join in the fight, but it is probable that any such combats at this stage of the battle only occurred against any Takeda cavalryman who had passed through the gaps in the fence. These gaps allowed the creation of a ‘killing-ground’ for such separated horsemen, who would become the prey both for samurai swords and ashigaru spears. Should any of the Oda samurai have ventured out from the fences it is likely that they would have been speedily recalled. Their time of glory was to come later. To add to the defence from palisade and spear quite dense clouds of smoke would also have been expected, a factor I saw illustrated dramatically when I observed arquebuses being fired at Nagashino in the annual festival in 1986.

The ideal situation for the Oda/Tokugawa army would therefore have been that the defensive measures outlined above would have given the arquebus corps sufficient time to prepare for three more volleys as the next wave of horsemen charged in. Subsequent events indicate that this ideal state was actually achieved, as successive mounted attacks suffered hundreds more mounted casualties.

While Takeda Katsuyori’s vanguard units were thoroughly engaged in the advance that they thought would sweep the Oda and Tokugawa armies off the field, a rear attack was taking place far behind them. It is unlikely that the Takeda army who charged the guns were aware until after the battle was over that Sakai Tadatsugu had launched his attack on Takeda Nobuzane’s forts of Tobigasuyama at 08.00. In complete secrecy Sakai Tadatsugu divided his unit into three sections. The first attacked the fort of Nakayama with such force that the defenders abandoned it for Tobigasu, which Sakai Tadatsugu’s other two divisions attacked in the ensuing confusion. Both attacks were begun with matchlock fire from the 500 gunners under Kanamori Nagachika, followed by the shooting of fire arrows onto the temporary buildings, whose thatched roofs soon caught light. There was then a charge into the compound by the samurai. The commander, Takeda Nobuzane, was killed in the fierce hand-to-hand fighting which ensued. Soon smoke was seen rising from Tobigasu by the besiegers of Nagashino across the Onogawa. But they were of vastly reduced strength and concentrated on the opposite sides of the river’s confluence, and so were powerless to intervene, all they could do was watch as one section of their army was annihilated

Looking from the fence across the plain of Shidarahara to the woods which divided the battlefield of Nagashino from the castle. This was the view that would have tested the mettle of Oda Nobunaga’s three thousand gunners as 12,000 horsemen emerged from the trees and came galloping towards them

Having been given permission by Oda Nobunaga, Sakai Tadatsugu leads a force of men against the Takeda siege lines on the hill of Tobigasu.

This view shows close-up detail of the fence which was to play such a decisive part in the battle of Nagashino. The fence has been reconstructed by Hôrai town council to commemorate the famous encounter that took place there four hundred years ago.

The chaos on Tobigasu had also been spotted by Okudaira Sadamasa and the garrison of Nagashino. They had long been aware that the bulk of the Takeda army had moved away. The noise from Shidarahara must have reached them, and when Tobigasu went up in smoke Okudaira Sadamasa gave orders for the gate of Nagashino castle to be opened, and he led a charge into the remaining besiegers. This sally is illustrated on the Nagashino screen. Further destruction of the Takeda army ensued, and in spite of the castle garrison being weakened from hunger and illness, they inflicted great damage on the besiegers. Of Kôsaka Masazumi’s unit besieging the castle, 200 were killed. The Tokugawa force lost one high-ranking samurai in the sally. He was Matsudaira Koretada, one of Okudaira’s two assistant commanders.

The right flank of the Oda/Tokugawa lines was marked by the absence of the defensive palisade which stretched across the rest of the front. Here the troops of Yamagata Masakage flung themselves against the samurai under Okubo Tadayo, and much fierce fighting took place.

Back at Shidarahara the attack on the Oda-Tokugawa line had now been continuing for three hours, and still the fence held, but the actual nature of combat varied from place to place. In the centre there was a straightforward fight between Takeda Nobukado’s and Naitô Masatoyo’s units and the Oda line, which held them in check in spite of repeated brave charges. We may perhaps envisage a series of rushes intended to break the gunners’ resolve, but as successive charges had to pick their way through the bodies of their comrades, the impetus soon passed to the defenders.

Over on the right wing the vanguard under Baba Nobuharu was experiencing great difficulty in coming to grips with the enemy, and suffering casualties as they did so. The densely forested hill to the right prevented any outflanking movement and served to funnel the charging horsemen into the gap. As Baba’s vanguard withdrew to rest they were replaced by the Sanada brothers, Tsuchiya Masatsugu, Ichijô Nobutatsu and Anayama Nobukimi. Again the matchlock balls tore into them. Tsuchiya Masatsugu was shot dead. Sanada Nobutsuna and Nobuteru lost 200 men to the firing but then managed to break through into the Oda lines where they engaged in hand-to-hand combat with Shibata Katsuie and Hashiba Hideyoshi, but both the Sanada brothers were killed. However, at this point Baba Nobuharu returned to the fray, determined to break through the fence towards Nobunaga’s headquarters. Here Sakuma Nobumori held the high ground, and as Baba Nobuharu advanced, he ordered a fake retreat. This drew the Takeda men on into the ‘killing zone’. They occupied the hill with great elation, and then proceeded to attack the next stockade from the side. However, Shibata Katsuie and Hashiba Hideyoshi had been prepared for such an eventuality, and attacked them in the flank and rear, driving them off with many casualties. Out of 700 men in his vanguard, Baba Nobuharu now had only 80 left.

Oda Nobutada (1557-1582) was the eldest son of Oda Nobunaga. He commanded the rearguard at Nagashino, and is shown here on a modern copy of the painted screen of the battle. His uma-jirushi (standard) was a large flag that bore the device of a white rectangle with a gold border.

The right wing of the Oda army was not protected by a fence, and in front of Okubo Tadayo was the veteran Yamagata Masakage, aged 60. Their encounter is well illustrated on the Nagashino screen. Okubo Tadayo has a sashimono of a large golden disc, while his younger brother, Okubo Tadasuke, wears a sashimono of a golden butterfly. They had fought the Takeda at the Battle of Mikata-ga-hara, and were under no illusions as to the task which was required of them. Unhindered by fences, and with a wider ground over which to operate than their comrades along the line, the Yamagata vanguard, with Masakage at their head, took casualties from the bullets and crashed into the Okubo body of troops. Here a fierce hand-to-hand fight developed as the first mêlée of the day, so we may envisage the Okubo ranks parting to allow the horsemen in. From this moment on the matchlock fire would only have been sporadic, as this area of the battlefield became one huge hacking mass of men and horses. The samurai sought single combat. The attendants tried to protect their lords, while the ashigaru spearmen and gunners lashed out at any they could see who were identified as enemy. As he had already demonstrated outside the walls of Yoshida, Yamagata Masakage was skilled in single combat, and still had the assistance of the three samurai who had attended him then. Yamagata must have stayed on his horse, because we then read of him breaking free from the mêlée and leading his men in a charge against the unit of Honda Tadakatsu. He was met with a hail of bullets and finally shot from his horse’s back. As he fell, an unknown samurai ran up and cut off his head, which was taken back in triumph.

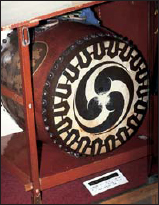

The Takeda attack on the palisade was launched to the sound of war drums carried on the backs of ashigaru. Another ashigaru would walk behind to beat it. This example is preserved in the museum on the site of Nagashino castle, and the caption proudly proclaims that it carries bloodstains from the battle.

At about this moment Takeda Katsuyori ordered a general attack along the line with all the reserves and his own bodyguard. He rode behind the unit of Takeda Nobutoyo in the centre, led by his vanguard under Mochizuki Nobumasa and followed by his rearguard under Takeda Nobumitsu. Yet even this brave attempt with fresh troops made no impact of the Oda-Tokugawa lines. So the battle continued as the morning wore on. In spite of the vast scale of the slaughter and the anonymity of many encounters, the chroniclers still found space to record certain individual feats of samurai heroism. In an isolated incident, Honda Shigetsugu of the Tokugawa force launched a single-handed attack on seven or eight enemy horsemen and killed two in spite of being wounded in seven places himself. Elsewhere, a retainer of Torii Mototada called Nagata Hatsumi-no-suke took the head of an anonymous samurai whose sashimono flag bore the characters ‘ni gatsu’ (February). After the battle he discovered that he had taken the head of an important leader called Mochizuki Nobumasa, who was Katsuyori’s cousin and commanded 60 horsemen in the goshinrui-shû.

Takeda Katsuyori leads his contingent into battle. In this section from a modern copy of the Nagashino screen Takeda Katsuyori is distinguished by the Japanese character meaning ‘great’ on his standard. During the battle Katsuyori commanded from a hill overlooking the battlefield, and only joined in the fighting when he committed his reserves.

Three gunners line up at Nagashino. This ‘firing line’ from the Nagashino festival gives a good idea of what may have been the appearance of the gunners at Nagashino, standing or kneeling shoulder to shoulder behind the wooden palisade. The firing of reproduction matchlocks is a well respected activity in Japan, and the club from Yonezawa represented here are much in demand for historical re-enactments

The hand-to-hand fighting continued until about 13.00. At this point Oda Nobunaga gave orders for the blowing of the horagai, the shell trumpets that were the pre-arranged signal for his army to withdraw into the line of the fences. Temporarily disengaged from their enemies, the Takeda began to retreat in the direction of the Hôrai-ji temple on the road back towards Kai province and safety. Seeing this movement, Oda Nobunaga ordered a pursuit. The Oda and Tokugawa samurai mounted up and rode out from the palisade. The first prominent person to be caught was the commander of the vanguard of the centre squadron, the veteran Naitô Masatoyo, who was accompanied by the 100 men left out of his initial command of 1,000. He was apprehended by Honda Tadakatsu, Osuga Yasutaka and Sakakibara Yasumasa, who had with them a number of ashigaru archers. They fired at Masatoyo, hitting him many times. He fell from his horse, and seeing him trying to lift his spear, a samurai called Asahina Yasukatsu thrust a spear at him and took his head. Masatoyo was 52 years old.

A gunner at the ready at Nagashino. Every year, on the anniversary of the battle, a major festival is held at Hôrai, centring on the castle site itself. Details of the arquebus may be seen in this picture of one of the gunners at the 1986 celebration. The matchlockmen at the battle were ashigaru, and would therefore not have worn such elaborate armour.

The most heroic death during the withdrawal was suffered by the other great veteran Baba Nobuharu. He took it upon himself to ensure Takeda Katsuyori’s safety by covering his retreat. When the Oda forces caught up with his rearguard unit, Baba Nobuharu announced his name in the manner of the samurai of old, stressing that only the greatest of samurai would take his head. The challenge was answered by two samurai, who attacked him simultaneously with their spears, and soon his head was off his body. He was 62 years old.

Takeda Katsuyori withdrew into his mountains, accompanied at the last by only two samurai retainers, Tsuchiya Masatsune, brother of the other Tsuchiya killed at Nagashino, and Hajikano Masatsugu. Swift messengers had already conveyed the grim news to Tsutsuji-ga-saki, and Katsuyori was met en route by Kosaka Masanobu, who had abandoned his campaign against the Uesugi and hurried down to safeguard Katsuyori’s entry into Kai. The appearance of this force on the border set a limit to Nobunaga’s pursuit, and Katsuyori escaped.

Takeda Katsuyori left behind him on the battlefield 10,000 dead out of a total Takeda army of 15,000, a casualty rate of 67 per cent. The losses were particularly acute among the upper ranks of the Takeda retainers and family members. These were the men who had led from the front and charged into the Oda-Tokugawa lines at the head of their followers. Out of 97 named samurai leaders at Nagashino, including generals of ashigaru, flag commissioners and samurai commanders in the goshinrui-shû and the fudai-karo-shû, 54 were killed and two badly wounded - 56 per cent of the total. No fewer than eight of the veteran Takeda ‘Twenty Four Generals’, the men of Shingen’s generation, lay dead: Hara Masatane, Sanada Nobutsuna, Saigusa Moritomo, Naitô Masatoyo, Yamagata Masakage, Tsuchiya Masatsugu and Baba Nobuharu. Losses on the allied side were also quite heavy – 6,000 killed out of 38,000, a rate of 16 per cent – but this did not compare to the tragedy of the Takeda that bore the name of Nagashino.