After such an overwhelming victory as Nagashino, it is perhaps surprising to note that the final defeat of Takeda Katsuyori did not occur until 1582. Following the battle he withdrew to Kai and maintained a defensive policy for the rest of his life. Kai and Shinano were easier to defend than the coastal provinces of Mikawa and Tôtômi, and the Takeda strategic position was also greatly helped by the death in 1578 of their great rival Uesugi Kenshin. The latter’s demise was so fortunate for all concerned that ninja were suspected, and following his death a succession dispute within the Uesugi family took a lot of pressure off the Takeda from this direction.

The Takeda strategy was now one of pure defence and survival. Tokugawa Ieyasu continued to harass them, and between 1575 and 1581 he conducted a series of operations against Katsuyori, which resulted in the regaining of Takatenjin Castle, lost before Nagashino. By this time even Katsuyori’s own subjects were beginning to lose confidence in him, and in 1581 he alienated many by building a new castle at Shimpu near Nirasaki, proclaiming it as his new capital. Shingen had never relied on a fortified place as his capital. Tsutsuji-ga-saki, his headquarters in Kofu, had been a one-storey mansion complex with just one moat. Now his heir, who had failed at Nagashino, was seeking refuge behind stone walls.

The following year one of the major Takeda vassals revolted. This was Kiso Yoshimasa, who held the castle of Kiso-Fukushima on the Nakasendô, which was almost at the limit of Takeda territory. Encouraged by such dissension, in 1582 the combined forces of Oda and Tokugawa turned against the Takeda. Oda Nobutada, Nobunaga’s son, invaded Shinano, and one by one the Takeda allies collapsed before them. Even Anayama Nobukimi, who had been one of Shingen’s Twenty-Four Generals and survived Nagashino, left Katsuyori for the winning side.

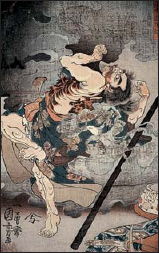

The warrior in the foreground of this picture is Baba Nobuharu, one of Takeda Katsuyori’s ablest generals, who was killed during the retreat. As Baba Nobuharu covered Katsuyori’s withdrawal he was challenged by two samurai. Nobuharu proclaimed his name and pedigree in the manner of a samurai of old, and was cut down. Behind him is Saigusa Moritomo, who was also killed at Nagashino.

This early print by Kuniyoshi, which is not of Nagashino, illustrates the effect of arquebus fire on the human body. The victim is a certain Yamanaka Dankuro, of whom no other details are known. The overcoming of the sword by the gun is a theme regarded as tragic by several samurai commentators.

Only his closest relatives now stood by him. His younger brother Morinobu, who had been adopted into the Nishina family, held out valiantly at Takatô Castle, along the route which the great Shingen had taken to his victory at Mikata-ga-hara. Then Ieyasu struck northwards into Kai, and the Takeda resistance collapsed. As the Tokugawa approached, Takeda Katsuyori burned his new castle of Shimpu and fled to the most distant mountains of his territory. Oyamada Nobushige, one of the old Twenty-Four who had stayed in the siege lines during the Battle of Nagashino, had offered him refuge in his castle of Iwadono, but when Katsuyori arrived, he found the gates shut against him.

By now his army had shrunk to 300 men. The only famous name from the original Twenty-Four Generals who remained with him to the last was the family of Tsuchiya. The three sons of Tsuchiya Masatsugu joined Katsuyori and his son Nobukatsu at their last battle at Torii-bata, a pass overlooked by a mountain called Temmoku-zan, by which name the battle is usually known. There were 30 survivors. As the Tsuchiya brothers held the enemy back Katsuyori’s young wife, aged 19, committed suicide by stabbing herself. Katsuyori, acting as her second, cut off her head, then with his son committed hara-kiri. The head of Takeda Katsuyori was sent to Oda Nobunaga for his inspection. ‘The right eye was closed, and the left eye was enlivened with a scowl.’ wrote a chronicler, ‘Nobunaga was moved to tears at the sight of the head of the great commander. All agreed that Nobunaga may have been victorious in battle, but was defeated by the head of Katsuyori.’ So died the unfortunate Takeda Katsuyori, the man who had supposedly been born as a act of revenge by a fox disguised as a beautiful woman. He is buried within walking distance of the place where he died, a tragic figure in Japanese history, the heir who inherited his father’s mantle but showed himself to be unworthy of it.

Bitter hand to hand fighting is shown in this section of a painted scroll preserved in the local museum, the Nagashino Castle Preservation Hall. Two warriors on the right, identified only as ‘Nobunaga’s troops’ press home their attack against Takeda Katsuyori and his loyal supporters at his last battle in 1582.

The Battle of Nagashino holds a unique place in Japanese history. The siege which preceded it is regarded as one of the three classic sieges of Japan, but it was the skilful manner in which Oda Nobunaga secured his victory which has earned Nagashino such a reputation. As noted earlier, Oda Nobunaga applied on a large scale the important lessons he had learned from years of fighting against a fanatic army composed almost entirely of lower class footsoldiers, who fought like samurai and compensated for their lack of skill in the traditional samurai weaponry by investing heavily in matchlock guns.

Nobunaga’s first achievement at Nagashino was to make a correct assessment of his enemy. He knew their skills, their strengths and their weaknesses, and had suffered defeat at their hands at Mikata-ga-hara. Their strength was their cavalry, but their weakness was that they would use their cavalry unadvisedly. The mere fact that Takeda Katsuyori planned to attack him, rather than use Nagashino for a defensive position, was evidence enough of the latter.

Hand to hand fighting is shown in this section from the Ehon Taikô-ki. The gunners at Nagashino broke the impact of the cavalry charge, and offered the samurai up for bitter and to hand fighting beside the palisade lines. This part of the battle lasted for the whole of the morning. Spears and swords were the common weapons used.

Nobunaga’s brilliant additions to the earlier situation he had experienced at Ishiyama Hongan-ji were threefold. The first was the creation of simple field fortifications, which were just sufficient to give the matchlockmen the protection and confidence they needed. This was combined with a sensible choice of ground. He opted to stand against the Takeda not on the hills directly overlooking the castle, where all their movements would easily be seen, but one range back, where the little Rengogawa would play a decisive role as a moat. The final factor was the rigid discipline supplied by his most trusted individual warriors from his bodyguard, who had loyalty only to him and did not have the responsibility of controlling their own units of troops. Oda Nobunaga thus produced a formula that was calculated to withstand the Takeda assault, and it worked perfectly. It was not a total victory in that it did not completely destroy the Takeda clan in one day, but it came very close to it, and the shock produced in Kofu by the returning wounded must have been tremendous.

There is some evidence that the experience of Nagashino produced something of a defensive mentality among other daimyô for years to come. This is shown by the subsequent behaviour of certain samurai generals who were present at Nagashino. In 1583 Toyotomi Hideyoshi fought and defeated Sakuma Nobumori at the Battle of Shizugatake, when the latter was in the process of besieging a castle. A rapid march by Hideyoshi’s army caught Sakuma unprepared with no fence for protection. One year later Hideyoshi prepared to fight Tokugawa Ieyasu in the area of Komaki castle. Both were veterans of Nagashino, and both prepared extensive defence lines and earthworks. A stalemate ensued, and was only broken when Hideyoshi sent an army to attack Mikawa province, which one suspects had as much to do with relieving boredom as any grand strategy. The resulting battle of Nagakute, fought far from the lines, was a pitched samurai battle in the grand manner.

This print by Yoshitoshi, which is concerned with one of the battles of the wars of Restoration in the 19th century, nonetheless conveys the feeling of swathes of samurai laid low by a hail of bullets. Interestingly, the victims include a drum carrier, whose drum bears the Takeda mon of four lozenges.

The experience of Nagashino certainly encouraged all daimyô to obtain more firearms, and as numbers increased, the advantage which Nobunaga had enjoyed was unlikely to be repeated. The situation of Nagashino was also difficult to recreate. A decline in mounted warfare may also be noted, so that at the final battle of the siege of Osaka castle in 1615, Tokugawa Ieyasu ordered his samurai to leave their horses at the rear and go in on foot with their spears.

There is, however, a persistent impression that the use of firearms was not really regarded as part of the glorious samurai tradition, and when peace came with the triumph of the Tokugawa, it was the samurai sword which became the cult weapon and badge of the samurai class, not the matchlock gun, in spite of the large number of the latter in the Tokugawa armoury.

The victor of Nagashino, Oda Nobunaga, was only to survive Takeda Katsuyori by a few months. He was murdered in 1582 by one of his own generals and was succeeded by Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who avenged his master with consummate opportunism. Following his successful command of the castle, Okudaira Sadamasa received the unusual honour of being presented by Oda Nobunaga with one of the syllables out of his name, so that he became known as Okudaira Nobumasa. He also received from Tokugawa Ieyasu considerable lands, a sword, and his daughter in marriage. Okudaira Nobumasa continued to serve Ieyasu, and took part in the final campaign against Katsuyori in 1582. He died in 1615. Tokugawa Ieyasu, of course, achieved the prize which had eluded Takeda Shingen, Takeda Katsuyori and Oda Nobunaga when he became Shogun in 1603, all rivals having been vanquished.

As for the castle of Nagashino, its days were numbered as a vital strategic fortress. The defeat of Katsuyori had been so catastrophic that it was highly unlikely that he would ever return to Mikawa by that route, so in 1576 the site was abandoned, and apart from the Iida railway line has remained as a rocky bluff above a fast flowing river to this day.