by Arthur Harman

Whenever an historical campaign or battle is to be recreated as a wargame the first decision that must be taken is whether to allow the players freedom of action, or to structure the game in such a way that they must abide by the strategic and tactical choices of the original commanders. If players have freedom of action, however carefully their briefings have been written, the game invariably fails to follow the exact historical sequence of events, and there is no reason to suppose that a wargame of the Nagashino Campaign will be any different. Who, after reading this book, would choose to send cavalry against a palisade held by ashigaru matchlockmen? This appendix will, therefore, suggest a variety of games, which may be played either in isolation or as part of a series, in which the players cannot reverse the most significant decisions taken by the original commanders, but must operate within those constraints, so as to recreate – insofar as any wargame can hope to do – the atmosphere of the historical sequence of events.

In the long term, Tokugawa Ieyasu was the real victor of Nagashino. His territories had suffered the raid by Takeda Katsuyori which led to the siege of Nagashino, and his Mikawa samurai greatly distinguished themselves in the subsequent batle. It was Tokugawa troops who led the assault in 1582 on the Takeda territories, which then became Tokugawa possessions, giving him the service of the renowned Takeda fighting men, and their equally renowned gold mines. He became Shogun in 1603.

Takeda Katsuyori’s invasion of Mikawa province may be recreated as a wargame using one of two very different structures.

The first is a conventional kriegsspiel in which each of the players has a personal copy of a detailed map of the theatre of operations, upon which to plan the manoeuvres of his troops, and gives written notes of his personal actions, orders and messages to other played characters and subordinate comanders, to an umpire or umpires. It is the umpires who will determine, on their master map, out of the players’ sight and earshot, whether and after how long orders or messages reach other players, when and how orders are implemented by non-played characters and when contact is made between opposing forces. They will decide what degree of knowledge the rival daimyôs should be given of events outside their immediate field of vision and report back to them accordingly. Such a game is said to be ‘closed’ because the players will be given, for example, no information of forces or events about which the umpires decide their characters would of have been unaware in reality, and do not administer any rules governing movement or combat themselves.

The second, the Matrix Game, developed by Chris Engle of the United States, is an ‘open’ game, in which all players and an umpire sit around one map of the area and the former take it in turns to propose Arguments, comprising of an Action and three Reasons why a desired Result of that Action should ensue, before the assembled company. Arguments, unlike the orders in a kriegsspiel, may apply not just to one’s own troops, but to hostile forces or to natural phenomena, such as the weather, although some umpires prefer to forbid players to make Arguments concerning forces or events of which their characters would, in reality, be unaware. The umpire, using a few simple principles and die rolls, will decide whether, and to what extent, an Argument succeeds and resolve conflicts between opposing Arguments, inform all players of the various outcomes and update the map where necessary.

The suicide of Takeda Katsuyori. A section from the painted scroll in the Nagashino Castle museum shows Takeda Katsuyori committing hara-kiri as Oda Nobunaga’s troops approach. Note how he has stripped off his body armour to allow himself to perform the deed unrestricted. The artist has depicted in a very graphic manner the moment when the abdomen is opened.

A Matrix Game, albeit not so realistic in structure, is a more sociable entertainment than a kriegsspiel, and thus ideal for light-hearted recreational play, and to generate tactical contacts which may be transferred to a tabletop to be fought out as battles with model soldiers. One could envisage a Matrix Game of the Nagashino campaign in which the players, dressed in suitable garments to suggest samurai costume, sat cross-legged on the floor, drinking tea or sake, around a specially drawn map, decorated in the Japanese style with characters and illustrations, upon which counters or bodies of small-scale troops, bearing appropriately coloured sashimono banners to identify their commanders.

Whichever of these two structures is chosen, the game will begin when Takeda Katsuyori, having invaded Mikawa province in the belief that Oga Yashiro would betray Okazaki castle to him, learns that the plot has been discovered and that he must abandon the attempt on the capital. His personal briefing should stress the need to save face by capturing at least one of the three castles along the Toyokawa. For purposes of the game, Nagashino should become whichever castle Katsuyori besieges and seems likely to capture, whereupon Oda Nobunaga will decide to march to support Tokugawa Ieyasu, and a battle between the besiegers and the relief force will ensue.

The principal players will, obviously, take the roles of Takeda Katsuyori at Asuke, Tokugawa Ieyasu at Hamamatsu, Sadai Tadatsugu at Yoshida castle, Okudaira Sadamasa at Nagashino castle and Oda Nobunaga. Other players could portray their relatives and vassals, so that the game could depict not just stategic manoeuvres, but also the initial raising of armies, involving the calculating and negotiating of troop contingents by reference to land holdings, and questions of clan/vassal loyalty and the possibility of treachery.

Siege wargames usually require different structures to portray different aspects of the conflict: the lengthy processes of erecting siege lines, bombardment, mining and starving out are best portrayed on maps or small-scale models in an umpire-controlled kriegsspiel, in which each turn represents one day; sorties by the garrison and attempts to carry outworks by storm can be recreated using 15mm or 25mm figures on a scale model of the appropriate part of the fortress. The contests for the various enclosures of Nagashino castle are eminently suitable for the latter type of game.

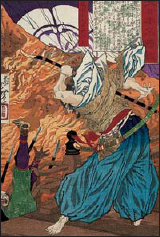

The death of Oda Nobunaga. Having had the satisfaction of contemplating the head of Takeda Katsuyori, Oda Nobunaga did not have long to enjoy his triumph, because in that same year he was murdered in the Honnôji temple in Kyôto by Akechi Mitsuhide, one of his generals. In this dramatic print by Yoshitoshi Oda Nobunaga uses his bow and arrows as the temple blazes around him. (Courtesy of Rolf Degener).

Existing commercial rules for medieval, fantasy or 16th-18th century European siege warfare can be easily adapted for this scenario, or a set of rules can be written specifically for the game.

The player commanding the Nagashino garrison will, at some stage, wish to send a messenger to Tokugawa Ieyasu. Escaping through the Takeda siege lines and returning if necessary can become a small, but entertaining game for a few players to enliven the slow progress of the siege, by employing the ‘Forest Fight’ system devised originally by Andy Callan for the French and Indian War.

The volunteer must elude pursuit by three groups of Takeda troops, each comprising one samurai and two or three ashigaru, not more than one of whom may be armed with an arquebus or bow. The playing surface or gameboard must be suitably painted and decorated with model trees to represent the forest around Nagashino castle. It comprises numbered identical sized squares, the faces of which are labelled A, B, C and D (or suitable Japanese characters that can be easily distinguished by the players), arranged in a random sequence – perhaps by the players taking turns to draw them from a bag or pile – that bears only a coincidental relationship to the true arrangement shown on a secret chart kept by the umpire.

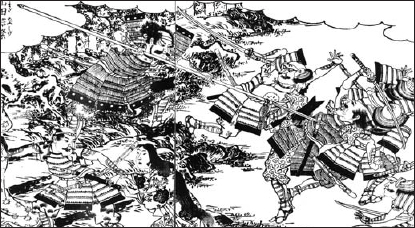

It is quite amazing to consider that in spite of the huge number of casualties at Nagashino the Takeda still managed to pose a threat to Oda Nobunaga until 1582. Takeda Katsuyori was finally defeated at the battle of Temmokuzan. This fine print is a different depiction of Katsuyori’s last moments. In this version his loyal retainers hold off the enemy as he prepares for death.

At the start of the game, 15mm or 25mm figures portraying the messenger and his pursuers are placed on their respective starting positions. Each player in turn is invited by the umpire to nominate the face by which he proposes to leave the square currently occupied by his figure or figures. The umpire then consults his chart and places all the figures into those squares into which they have moved, which may well not be any of those adjacent to their starting positions. The messenger must endeavour to traverse the gameboard without being caught to exit by a particular square, whereupon he will be deemed to have eluded pursuit and be able to deliver his message to Tokugawa Ieyasu. The Takeda troops must try to stop him, by entering the same square as the messenger and defeating him in hand to hand combat. The umpire can, at his discretion, allow the ashigaru matchlockman or bowman to shoot at the messenger if the latter is moving across an adjacent square on the secret chart and the ashigaru is facing in the right direction to catch a glimpse of him. Combat can be resolved using simple skirmish rules, variants of ‘Paper, Scissors, Stone’ or other systems devised for the occasion. A return journey by the same messenger should be played with the squares in different positions, but the same umpire chart. In such a case the Takeda may nominate certain squares as containing traps before play commences. Attempts by different messengers require the creation of a new chart, however.

Such a game can be played to determine whether the Nagashino garrison summons assistance successfully, whether it learns that a relief force is on its way, and whether the Takeda besiegers also learn this fact, before one of the battle games described below. Suitably adapted and extended, this game might also be used to recreate the exploits of Torii Sune’emon.

Oyamada Nobushige, who led 200 horsemen on the left wing of the charge at Nagashino, managed to survive the battle and escaped to his castle at Iwadono. In 1582, when the Tokugawa pressed home their attack into the Takeda territories, Takeda Katsuyori fled to Iwadono, only to find the gates closed against him.

The obvious problem if one is trying to recreate a battle, whether it be Nagashino or Agincourt, in which one army launched an attack, which hindsight suggests was probably doomed to fail, is how to persuade one player, or a player team, to make such a charge when the outcome can be predicted?

A wooden lookout tower such as would have been used at Nagashino castle. This reconstruction is at Ise Sengoku Jidai Mura

One could endeavour to recruit players who are interested in samurai warfare of an earlier period, but have little or no knowledge of the Sengoku-jidai and this particular campaign.

The briefing for Takeda Katsuyori must encourage him to believe in the efficacy of his cavalry, emphasise the defeat of the Tokugawa at Mikata-ga-hara in 1572 and downplay the tactical importance of firearms in battles, but stress the necessity of using his own arquebus corps to maintain the siege of Nagashino castle. His aim must be to drive the relief forces of Tokugawa Ieyasu and Oda Nobunaga off quickly, before they can establish themselves in the area.

Oda Nobunaga’s briefing must describe in detail the tactical lessons he has learned from campaigning against the Ikkô-ikki – the efficacy of arquebus volley fire by ashigaru or peasant troops when secure inside field fortifications – and his troops’ use of long nagae-yari as units of pikemen. It should explain how a palisade can break up a cavalry charge into small groups of samurai horsemen, who can then be despatched by his own samurai and ashigaru.

Another possibility would be to disguise the scenario for the Takeda players, whilst remaining within the Sengoku-jidai, so that they believe they are playing an earlier battle – such as Mikata-ga-hara, perhaps – and so have either no knowledge of, or a poor opinion of, firearms and cannot anticipate their use en masse by Nobunaga’s troops.

Alternatively, the Game Organiser can avoid the whole issue, without attempting to disguise the battle being fought, by adopting a game structure in which only one side is actively played.

The Takeda army could be programmed by the umpire to act historically, and all players would command contingents in the Oda-Tokugawa forces. The initial charges by the Takeda cavalry would become a ‘space invaders’ type shooting contest, followed by a mêlée, which would then focus on the personal experience of individual samurai and their retainers in hand to hand combat, as described below.

Another idea would be to recreate the perspective of individual Takeda samurai and their retainers in the charge, as a combined skirmish/roleplay game. The effect of volley fire from Oda Nobunaga’s matchlock armed ashigaru would be determined by die rolls in conjunction with wound tables created specially for the game, based upon the results of the experiments described in this book. [See my appendices to Balaclava 1854 and Alexander 334-323BC in the Campaign Series for further ideas for gaming an individual cavalryman’s experience of battle]

In either case, to ensure an enjoyable game, but unbeknown to the players, during the early charges the umpire would only implement mortal or disabling wounds upon horses, non-played characters and retainers, so as to keep players, who might be lightly wounded, in the game for as long as possible – at least until the Takeda cavalry reached or penetrated the palisade and engaged in hand to hand fighting with umpire-controlled Oda-Tokugawa samurai and ashigaru. Players could dice to summon the assistance of their personal retainers (provided they had not been killed or wounded already) in the mêlée. Each player’s personal objective would be to survive, or die an honourable death and take as many heads heads of the enemy as possible.

Should the Game Organiser and the players, however, prefer a wargame in which both sides are controlled by the participants, it will probably be necessary to structure the recreation to commence only after the volley fire has decimated the Takeda cavalry, so that the game portrays the subsequent mêlée. This stage of the battle could be gamed in two ways, depending upon the players’ tastes and the resources available.

A display of the entire Shidarahara battlefield, using small-scale – 1/300 or 6mm – models or troop counters for each contingent could be used to create the generals’ perspective. Figures representing the tsukai-ban would be used to deliver the commanders’ orders to troops not under their personal control. Combat would be controlled using stylised rules such as DBR.

Alternatively, the game could focus on the experience of just one clan within the battle in a tactical game with 15mm or 25mm models: the obvious choice, to offer a fairly even chance of success to both sides, would be to recreate the attack by Yamagata Masakage upon Oda Nobunaga’s right wing, unprotected by the palisade, commanded by Okubo Tadayo.

Sakai Tadatsugu’s attack upon Takeda Nobuzane’s forts of Nakayama and Tobigasu should be refought simultaneously with the action at Shidarahara, but out of sight and earshot of the players of the latter, as either a figure game or a kriegsspiel. The result should only be communicated to the Takeda players at the end of the main battle. Once Tadatsugu’s troops have captured or set fire to Tobigasu, the sortie by Okudaira Sadamasa’s garrison may also be fought out, if desired. These actions could also be fought as a self-contained game, in which the battle at Shidarahara is not played, but assumed to be following its historical course.

This life sized reproduction of the charge of the Takeda cavalry at Nagashino is at the Ise Sengoku Jidai Mura. The dummies are made of fibre glass. During the daily performance the horsemen are bombarded with fire and smoke from fibre glass ashigaru.

The reconstructed fence at Nagashino viewed from about 200 metres away across the Rengogawa. This is about the maximum range for the arquebuses to do real damage, but firing probably did not begin until the horsemen had crossed the river.

To conclude, here is a radically different approach for readers who neither possess nor wish to acquire samurai armies: set the campaign in the Wars of the Roses! This will avoid the problem of trying to create a non-European atmosphere for this wargame. For the daimyô who fought at Nagashino, just as for the 15th century English nobility, the campaign was part of a long power struggle between leading families for territory and effective control of the government.

So, let the Shogun be Henry VI, Takeda Katsuyori the Earl of Warwick, ‘The Kingmaker’, and Tokugawa Ieyasu and Oda Nobunaga two noblemen who support the House Of York. Nagashino becomes a medieval castle, the samurai, knights and men at arms and the ashigaru English yeomen archers, spearmen and handgunners. Scale down the forces to a size more suited to the Wars of the Roses and let battle commence – in this setting the tactical ploy of palisade and volley fire, whilst technologically possible, will not be suspected.