Working on a book with a story that largely finishes over 100 years ago doesn’t give the opportunity for first-hand interviews. Contemporary first-hand accounts in the form of memoirs, official documents and media reports are invaluable but far less personal than the anecdotes handed down through a family or the impressions that ancestors leave on their descendants.

I was delighted when I had the opportunity to interview Nigel Preston, James Billington’s great-great-grandson and William Billington’s great-grandson. Some of the stories do not have full details of which cases they relate to, but, wherever possible, I have tied these up with quotes taken from William Billington’s own memoirs.

When did you first become aware of your family history?

I was about five or six when another kid on our street told me that my grandmother was the hangman’s daughter, then to prove it he dragged me into one of the houses where an older person confirmed that it wasn’t just my great-granddad but the whole family that had been hangmen. That was what started my interest in it all.

My dad also knew William well. When William died it was the same day that my elder brother Alan was born. One of the things that Annie always repeated was that William’s death had been reported on a number of occasions in newspapers and magazines, quite falsely actually because he didn’t actually die until 2nd March '51. And what’s always been a source of amusement in the family is the strong resemblance between William and Alan at the same age.

There is only one source of the Billington family name so, barring infidelity and adoption; all people with the Billington name are related. The name originated from a place called Woodplumpton, just north of Preston in Lancashire and dates back to the mid-1500s. The family were Catholics at that time.

Your grandmother, Annie, was the daughter that William was charged with failing to maintain. What was her relationship with William?

It was hard to get Ann Billington to talk about her father. When I was a young person she was very dismissive and didn’t really want to get into conversation about him. I really had to work on her for a number of years and it became clear that she loved her mother, had strong admiration for her mother who’d brought her up against the odds, but she had very little time for her father. Interestingly though, my father, Alan, who’d obviously met William Billington a number of times over the years, said that when William died Annie was very upset about it. Very, very upset, although she had this deep bitterness and resentment which she eventually told me stemmed from the fact that he’d abandoned them. This was a great disgrace; she was a very proud woman, typical of the working class, especially in the North. They had these little terraced houses and they were always immaculate, the front step always scrubbed and they always had their Sunday best outfit – appearance was everything so imagine ending up in the workhouse with her mother. In some accounts I’ve read about her brother, but she never mentioned him.

That’s interesting, he’s on the 1901 census which shows William and his wife Catherine living in Mill Street, Bolton with a son, Edward.

Ann Billington did have a brother, Edward Billington, who was born in 1898 but I know little about him, Ann never discussed him. This Edward Billington married an Emily Hardman and they had a daughter, Ann Billington, who was born about 1925 in Bolton.

How would you describe Annie, your grandmother?

She was quite funny; she took some of her characteristics from her mother. I remember from when I was a young kid, she had all these different tins, and when Joe used to bring the weekly wage in that was paid in cash she met him at the front door and the cash was taken off him. There was a tin for rent, a tin for food money, a tin for coal and various other things they had to do, like save up for a holiday, there was a tin for that. My grandmother had her own banking system that she kept in a sideboard that had actually belonged to William and his wife Catherine. The tins and the sideboard are still in the family and represent the pride she took in paying her bills on time. She gave Joe a daily beer allowance and neither Joe nor his mates would ever cross her. At the same time she was as soft as anything with the kids.

So there was this deep, deep shame of her being in the workhouse, it almost brought her to tears whenever she talked about that period.

How well did she remember it?

She remembered the emotion. She was quite young and the workhouse time was brief but connected with it was the fact that William had abandoned them.

I think that was about 1905, when his hanging period finished. My personal theory is that things were getting on top of him, I think he fled just because he was stressed and suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. He just disappeared.

His disappearance is interesting in itself. For one thing there’s mention in several accounts that Thomas also disappeared, which makes you wonder whether it was the same thing.

William came back, and the best date I have is that it was around the time that Ann Billington married Joseph Preston, my grandfather. Ann would have been twenty-one or twenty-two then. So the absence was at least eight or nine years.

Do you have any idea how he spent those missing years?

My father spoke to William on a number of occasions, he used to go round to see his grandfather and had a bit more time for him than Annie did – got the impression that Annie had a deep resentment but also a deep need to be loved by her father.

William told Alan, my father, that he’d been in Newcastle for that time period and my father always wondered whether he’d had a second family. When I pressed my dad he couldn’t give any reasons other than wondering what William had been doing for that time period by himself. It would have been natural perhaps for him to partner up with someone else. But when he came back onto the scene he lived with Annie’s mother as a married couple until the day he died.

Even when he spoke to my father he wouldn’t be pressed into talking about the hangings, it was something he wanted to leave behind him.

I understand that your grandmother was once in possession of James Billington’s diaries. Can you tell me what they contained and what happened to them?

Someone had called at her house when she lived at a place called Charles Rupert Street, allegedly from a newspaper, and looked through the diaries with her. And what was in the diaries – they belonged to James but it was also William’s diary, he just continued on with that diary from his father.

I never saw them, I was far too young, but I got the impression from my grandmother that they disappeared about 1961 or '62 when I was four or five years old, but from her accounts James had lots of diagrams and had calculated heights and weights and drops, certainly she’s got his notes from the hangings of how much drop he’d given to people, the way that he assessed people’s weights, he’d have a look at them, he never actually met people prior to them standing up onto the gallows. But he’d always have a look at them through the spy hole into the cell; a lot of the technique was assessing their proportions in relation to body weight to calculate the drop. There were drawings in there of different apparatus and certainly notes about the hangings and who people were etc. and William had continued on with that. It’s a bit disappointing for me that they’ve gone. I’m hoping that someone’s kept them; I’m hoping that sometime they’ll get into the public record and I’d certainly like copies of them.

Which newspaper was the reporter working for?

She never actually said which paper it was. I pushed her on it and eventually she said she thought it was the Bolton Evening News but that was only after some questioning from me, so she could have said that just to shut me up. I wrote to the Bolton Evening News asking if they had an archive or library but I just got a very polite letter back to say that they didn’t have an archive, that they had no knowledge of the diaries. I just hope that whoever took the diaries has kept them, the biggest fear you have with things like that is that they die and relatives don’t understand the relevance of them, then they end up being thrown in a dustbin. It would be tragic.

So neither you grandmother nor your father divulged much about the contents of the diaries beyond their general structure?

I never got real detail. When I was younger my grandmother never wanted to discuss details of the executions, she probably felt they weren’t for the ears of a young child but I was absolutely fascinated by it. Being the hangman’s daughter gave Ann a certain amount of celebrity; people knew who she was just passing her in the street. She used to talk about James but obviously she’d never met him but she’d always wax on about James and how he was ‘a good guy’ even though he was the national executioner for so many years. William had been an executioner for a far shorter period but she gave the impression that he was a drunkard and a wastrel, whereas she always portrayed James as a teetotaller and lay preacher. I always thought it was a bit odd – why does this lay preacher end up as a publican?

As well as the diaries, was anything else taken by the reporter?

Photographs. A few, no more than ten, but Annie would reel them off, like the one of her Christening showing both her parents. I don’t know whether there were any of James, but given the fact that she ended up with the diaries it is possible.

One of the people that feature heavily in the Billington story is William Warbrick; did you hear anything of him from your grandmother?

From what William had told Ann there was always a lot of bad blood between him, and in fact the whole Billington family, and Warbrick. On several occasions Annie mentioned the incident when John fell into the pit at the execution of Tattersall. She quoted her father William when she said, ‘There’s real bad blood with Warbrick.’ The family were convinced that it had been a deliberate act.

Annie was also always saying that William (Billington) trained the Pierrepoints. She also said that James had trained Thomas, John and William. She claimed that William had never been that keen even though he was the most prolific of the sons. She came to that conclusion because of what happened later. James really pushed himself forward to become the executioner but it became clear that towards the end of his career he found it more and more distasteful.

Annie said that none of them liked hanging women, they really found that extremely distasteful, James had had a problem with some of the female executions that he’d done. One of the things that was always a claim to fame for Annie was that William was the first to hang two women together, they were the baby farmers. Annie also made reference to one woman who had to be virtually lifted onto the drop. It was a case that really badly affected William, she was almost comatose. When William described it to Ann he’d said he’d had to almost drop her through. I’m not sure who it was though. Annie said he had disturbed sleep and would often shout out in the night, as if he was reliving certain things.

This story seems to relate to the execution of Sach and Walters. In William Billington’s memoirs he says:

The knowledge of the crime for which Mrs Walters and Mrs Sach had been sentenced was quite sufficient to make me very ready to carry out the execution.

When I thought about the helpless babies, who we were led to believe had been murdered by these women, my blood boiled.

I recognised from the first that this was not likely to be a pleasant job. Holloway prison officials were not used to executions. In fact, I believe this was the first execution which took place at the women’s gaol.

However, I was to have an able assistant, and I foresaw no trouble.

I remember that after our arrival at the gaol on 2nd February we were conducted to very comfortable quarters near the main entrance.

Our first care was to take a look at the women through the inspection openings in the doors of the condemned cells. Then we discussed and decided upon the lengths of the drops to be allowed.

I remember that Mrs Sach, being the lighter built of the two, had a longer drop than her companion in crime.

We arranged the execution chamber on the morning of the 3rd. The nooses were fixed just far enough apart to allow of a plank being put across the drop doors for a wardress to stand on between the women. As things turned out, this precaution was necessary, but I believe my companion, Pierrepoint, was in great part responsible for the fact that the drop fell before Mrs Sach collapsed completely.

Pierrepoint stood at the edge of the drop and held the woman, and reassured her during the second it took me to get to the lever and pull it over.

Again I am going too fast – there is the scene in the cell occupied by Mrs Sach about which I must speak.

I entered this cell a few minutes before the hour fixed for the execution. Immediately Mrs Sach gave a piercing scream and fell in a heap on the floor. Two wardresses were quickly on their knees rubbing her hands and urging her to pull herself together.

She rallied, and after a moment or two managed to stand on her feet again.

Pierrepoint assisted me to fix the straps and hardly was the task completed when the woman collapsed again.

It was one of the most trying experiences I have ever had.

There was no time to be wasted in giving way to sentiment, however. I hastened into the next cell, and Mrs Walters, who showed not a sign of nervous tension was pinioned in a trice.

We hurried her into the cell, where her companion was still recovering from her collapse. It looked impossible that Mrs Sach would be able to walk to the execution chamber, though the distance was only a matter of eight or ten paces.

We formed the usual procession, with the Sheriff, governor, chaplain, and medical officer, and proceeded into the passage. Mrs Sach was helpless. She was hardly conscious, and wardresses practically carried her.

Speed was now the great essential.

All this time, although they had not seen each other for many days, the two women did not speak to each other. Not a word of greeting or sympathy passed when they first confronted one another in the condemned cell.

Once we had the women on the drop doors we lost no time in getting the ankle pinioning done and in fixing the nooses and white caps.

Mrs Sach was swaying, and Pierrepoint sprang to support her, while I made all haste to the lever. I saw the two women upright side by side, over came the lever, and I breathed more freely as I realised that we had got through a difficult task without mishap.

At the subsequent inquest the doctor was able to tell the jury that death had been instantaneous, and satisfaction was expressed with the way the execution had been carried out.

I shall never forget the smallest detail about that visit to London. I am not a nervous subject, but I am willing to admit I had been through a strain, and Pierrepoint has admitted that he felt no better than I did.

It seemed to be a bit of a turning point for William; it was always preying on him. The woman was distraught and almost fainting and they had to virtually throw her down the drop, instead of having her standing there she had to be supported. He found it quite traumatic. And I wonder whether that had been the catalyst for William going to pieces; he was executing people for another year or so, but if you take anxiety and post- traumatic stress disorder that’s the way it comes out, over time.

Could you see yourself in William’s position?

I’ve often thought that if I was in a battle or life-threatening situation I could kill somebody if I needed to – if it was my life or theirs, or if they were threatening a loved one or innocent person. But to kill someone in cold blood, so to speak, is a completely, completely different ball game.

You’ve had a career in the police force, so there’s a crime-related connection in the family. Have you ever considered that there might be something inherited or genetic about this? And secondly, it is one thing to have a burning ambition to do something but another for a man to encourage their children into it, it doesn’t necessarily follow that their children are going to find the same level of enthusiasm. How do you think this applies in the case of the Billingtons?

By coincidence, Annie worked at Bolton police station as a cleaner. I have wondered whether their could be some kind of genetic influence, especially as my brother also joined the police, but with John, Thomas and William, I think they became hangmen out of a strong sense of duty towards their father.

My grandmother’s favourite saying was that the Billington executioners were as famous as The Beatles, which used to make me laugh and I never really thought there was a great amount of truth in it. Often, however, the barber’s shop would be packed, and when they had the pub that was always packed. Everyone wanted to go to ‘the hangman’s pub’.

Jack Bradshaw, who was my maternal grandfather, he had a pub, the Crawford Arms, Bolton Street, in Bolton, and also knew William Billington, as William was his daughter’s grandfather-in-law. Joseph and Annie would often go to the pub and Jack would always comment how it was a pity that he wasn’t a retired executioner because he knew how busy it had kept James’ pub, the Derby Arms. Jack’s view was that William Billington was attracted to doing executions because it would make the other areas of his life quite lucrative; he’d make more from the fame than the actual executions themselves. As much as they didn’t want to talk about the executions they were still happy to take the money over the counter – it wasn’t in a nasty sort of way but that’s how it was portrayed.

Annie often mentioned James and his barber’s shop but when you look through the various documents it’s interesting how many different occupations are listed.

When I was young Annie mentioned James, her grandfather quite a bit, though she hadn’t met him, and I’d wonder what the source of information was. She talked about him dancing and singing, two things I’ve always enjoyed.

Was there any particular story which William was fond of telling?

William would often tell a story of when he had gone over to Ireland to hang an IRA man. He arrived a day early and the following day was sitting in a local pub. He noticed that outside a crowd was beginning to gather as if waiting for something. William asked what was happening and was told, ‘It’s because the executioner’s coming over.’

William apparently replied, ‘Well he deserves all he gets.’

He always found the story amusing, it was one of his favourites, he was pleased that he’d got away with it.

There is a similar incident in William’s memoirs which occurred before the execution of Donovan and Wade:

I had instructions to report at Pentonville in time to carry out the execution on the 13th of December, 1904. Pierrepoint was to be my assistant. I was warned that in certain quarters there was sympathy with the condemned men, and I must keep my eyes open.

When I got to London I found a cab waiting to take me to the prison.

‘Drive on with the cab,’ I said. ‘If anyone wants to hurt me they’ll think I’m inside. I’ll walk quietly after you.’

The Billington family has not been noted for its tall men. I am like my father, rather on the short side. Before I had got far from the station I began to wonder if I had taken the proper course. I had paused to get my bearings when I heard a gruff voice say, ‘Let me get hold of the little blighter and I’ll bet he won’t do any executing.’

I looked around and saw a burly fellow towering above me.

Fortunately, although he was ‘waiting’ for me, to judge by his conversation, he did not know I was so near him. And I did not stay long enough for him to find out.

With all speed I got to the gaol and breathed more freely when I was in my quarters.

Pierrepoint and I had a chat and made our arrangements and then retired for the night.

This seemed to be the inciting event for the railway incident. Police investigation cast doubt on William’s story that he’d been thrown onto the track as part of an assault, suggesting he was possibly just drunk. How do you think this fitted with what you know of William’s character?

My father’s view was possibly more balanced than Annie’s, but he’d also only known William in later life. He felt that William mostly drank at weekends, and claimed that he’d never seen him heavily drunk.

Did William ever comment on James’ claim that he’d hanged Jack the Ripper?

Annie and my dad often spoke about Jack the Ripper. William said that he may have hanged him. He wasn’t convinced that he had but he mentioned that he felt it was a possibility. The most famous case within the family was the baby farmers, he had a strong distaste for hanging women but he also really hated what they’d done. He was faced with a dichotomy; not wanting to hang women but really feeling that what they’d done was a totally evil act. The worst premeditated act he’d come across. Because they’d taken money and promised that the babies would be looked after he found it one of the cruellest cases. Whereas with a lot of the others he had some empathy, some respect for the people he was hanging. They were often sorry too.

William frequently commented that anyone could end up committing murder, you just needed the right circumstances and in a flash of a second you could do something that you’d regret for the rest of your life.

My dad asked him whether he felt any vengeance towards the people he executed, but he said ,‘No, it could be anybody.’

Did he ever make any comment about the possible innocence of anyone that he’d executed?

No. No, I often asked my grandmother because it’s one of the most interesting questions, but no, he never took a view on it. I think what he hid behind was that the decision had been made by the judge and the jury and didn’t need him. It was their job to make that decision and his to carry it out; he wasn’t killing people, the judge and jury were.

What do you think of the reports that he wanted to return to the post after he’d left?

This is a contradiction, Annie claimed that he had wanted to finish with the hangman’s role because he no longer had the stomach for it, and had felt this almost to the point of becoming anti-capital punishment.

At the time of his death James had his three youngest children living with him; Alice (eighteen), James (fourteen) and one-year-old May. May was the only child of his second marriage and of course lost both parents in quick succession. Do you have any idea what happened to this part of the family?

None whatsoever. The three adults, James, Alice and Thomas were all dead within months of appearing in the 1901 census. It might be that the publication of the 1911 census will shed some light on it. That may also solve the mystery of William’s whereabouts during this time.

Do you know whether William had been working as a barber during the time he was away, or was it a trade he only took up after his return?

He set up a barber’s shop on his return, but my father also mentioned that he worked as a blacksmith. In fact he’s listed as a blacksmith on Anne’s birth certificate. I know he’d also worked as a labourer. We have no idea how he’d earnt a living during the time he was away. That period included the First World War and I know he wasn’t in the army; he was forty in 1914 so he was too old to be called up.

Apart from being hangmen, the Billingtons were also barbers and publicans. Have any of the trades survived within the family?

No, none of them, but especially not the trade of executioner!

There was some religious background in the family; did William turn to religion in his latter years?

No, my father was an atheist and as far as I know William never held any strong religious beliefs. As much as William liked to think that it was the judge and the jury that were responsible for the deaths he obviously wasn’t dealing with it, but he didn’t find the answers by turning to religion either.

He liked reading; he read the paper every day. He’d comment about articles, especially relating to capital punishment. He became opposed to it. He had sympathy for the executioners and felt that it was too much of a job to ask of one person. Everyone who did that job would at some point regret it … he never said that in such a direct way but my father felt that that was what he was edging round all the time.

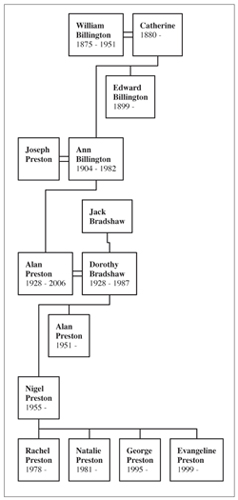

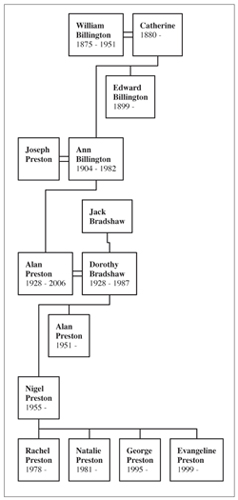

Selected family tree for Nigel Preston. (Author’s collection)