Sith and Republic warships clash above Coruscant (John VanFleet)

“Never interrupt your opponent while he is making a mistake.”

—Firmus Nantz, admiral, New Republic

In 5000 BBY an armada of alien warships launched an unprovoked attack on the Koros system. This marked the end of two thousand years of peace—and introduced the galaxy to the Sith.

The reason for the attack was brutally simple: The supreme Sith Lord, Darth Naga Sadow, had discovered a secret hyperlane leading directly from his Outer Rim despotate into the peaceful systems of the Republic. The route had been revealed to him by a naïve exile from Koros whom Sadow now proclaimed as “liberator” of his home system—a liberator accompanied by a brutal Sith occupation force.

The Republic scouts Gav and Jori Daragon had blazed that hyperspace trail from the Core to Sith Space, discovering an empire in crisis. The distances separating the far-flung Sith baronies had eroded technological knowledge and choked off economic development. The old aristocracy had been replaced by brutal half-caste warriors, who emulated the ancient kings with self-destructive quests for absolute power. And the distant Republic was rumored to be plotting the overthrow of the Sith, to impose alien laws and the religious tenets of the Jedi Order.

Sadow, viceroy of Khar Shian—who was raised from birth to fight these threats—taught that only ruthlessness could save his civilization. He had rebuilt his military, reinforcing traditional missile frigates with battleships and starfighters. Massassi warriors now carried blaster rifles alongside their traditional bardiches, and blaster turrets crowned the backs of their elephantine cavalry. The lesser barons’ levies were still dominated by tribal spearmen—but so were the armies of Republic outliers like Kirrek and Nazzri. Besides, throwing disks could skim through deflector shields, and war beasts could stride where armored vehicles could not.

When the Daragon twins arrived, Sadow kidnapped them, murdered his own Sith mentor to frame the Jedi for the crime, and created an invasion scare that secured his election as supreme viceroy of the Sith Empire. He then lured his rival Ludo Kressh into a trap, corrupted Gav Daragon with Sith training, and tricked Jori into returning to Koros aboard her scoutship—blazing a path for his armada to follow.

From their bridgehead at Koros, Sith raiding squadrons attacked Shawken, Metellos, and Basilisk, spreading panic and making defending fleets dance in response. But Sadow had reserved the most brutal attack for Coruscant itself.

An army of Massassi landed in Galactic City—barbaric, red-skinned alien slaves, bred for war and armed with spears and throwing disks. At their head rode Sadow’s chief lieutenant, Shar Dakhon—a feudal lord in gilded armor, mounted on a mighty war beast. Their brutal attack on the Senate Building was made possible by battle meditation, a dark Force technique that gave the warriors suicidal strength, and conjured fearful fantasies in the minds of their opponents.

Eventually the Republic turned back the dark tide. Its fleets developed flanking maneuvers that proved effective against the Sith frigates, while on Kirrek and Thokos, Jedi leadership enabled the defenders to drive off Sith invasions. On Cinnagar, Gav Daragon was confronted by his twin sister—and, realizing the error of his ways, surrendered to the Republic. The Sith had lost control of their bridgehead in the Core.

Facing defeat, Sadow pulled back most of his combat warships to Goluud, hoping to ambush the Republic there. But Gav Daragon martyred himself to give the Republic another key victory. Utterly defeated, Sadow retreated to his Outer Rim throneworld of Korriban. At that point, the Sith armada apparently broke into squabbling factions—for when the pursuing Republic fleets arrived, they found the wreckage left by a great space battle.

With their missile tubes empty, the battered survivors of the Sith armada lacked the firepower to resist the Republic’s turbolasers. Sadow fled, leaving an overmatched remnant to fight a doomed battle in defense of Korriban. With the armada destroyed and Sadow deposed, Chancellor Pultimo authorized a full-scale invasion—and Sith Space was liberated from its tyrannical ruling caste.

Excerpted from “Industry, Honor, Savagery: Shaping the Mandalorian Soul,” keynote address by Vilnau Teupt, 412th Proceedings of Galactic Anthropology and History, Brentaal Academy, 24 ABY:

After being driven from ancient Coruscant, the Taungs relocated to Roon and then wandered the Outer Rim, leaving hints of their passage in various species’ chronicles and histories. But they attracted little notice until they conquered Mandalore around 7000 BBY.

At the time, Mandalore lay beyond the galactic frontier—but close to the Republic’s outlying trade routes. Soon, rumors reached the Republic of worlds ruled by ferocious warriors. They served the god Kad Ha’rangir, whose tests and trials forced change and growth upon the clans he chose to be his people. In opposition to Kad Ha’rangir stood the sloth-god Arasuum, who sought to tempt the clans and drag them down into stagnation and idle consumption. By waging war in Kad Ha’rangir’s name and according to strict religious laws, the Mandalorian Crusaders defied Arasuum and showed themselves worthy of favor.

The Crusaders fought the Mandallian Giants at Mandalore, but were so impressed with their prowess in battle that they agreed to coexist, and in time would admit them into their clans. They raided Fenel, a powerful, isolationist world known for its shipwrights and technologists, culminating with the Fenelar’s extinction by the 6700s BBY. Armed with Fenelar technology, the Mandalorians then turned their attention to the Tlönians, a vicious arachnoid species known for their poison-sacs and habit of preying on ships foolish enough to stray beyond the frontier. Tlön was depopulated and incinerated by the 6100s BBY. Other worlds were spared: The Jakelians, for one, welcomed their new Mandalorian overlords, as did knots of worlds populated by humans centered on Concord Dawn and Gargon. Those worlds—along with the likes of Hrthging, Breshig, Shogun, and Ordo—became part of Mandalorian Space.

The Republic kept a wary eye on the Mandalorians, lest the Crusaders turn their attention Coreward to Nouane, the Obroa-skai region, and the wealthy trade worlds of the Great Tirahnn Loop. But while Crusaders did harry Republic settlements—sparking such skirmishes as the Pathandr Fury in 5451 BBY and the Nakat Incursions of the 5130s BBY—for the most part they remained beyond the frontier, pursuing their own mysterious missions.

The few Republic traders who knew Mandalorian Space had an unsettling message for the Republic: While the clans were given to jostling and quarreling, all heeded the commands of the clan leader, known as the Mandalore. And despite their nomadic ways, they were great tinkerers and canny technologists, improving Fenelar warships, Jakelian edged weapons, and even Republic rocket packs.

The final years of the fifth millennium BBY brought a Taung religious reformation. Instead of worshipping Kad Ha’rangir, the Taungs elevated war itself to the pinnacle of their cosmology—to make war was effectively to be divine. The reasons for this momentous change are imperfectly understood, but Mandalorian legend holds that the clan leader known as Mandalore the Indomitable had a vision while on the mysterious world of Shogun, returning to the clans with word of the revelation he’d received.

Soon after this reformation, the Crusaders raided the galaxy’s central systems. In 4024 BBY they attacked the planet Nevoota in the Colonies, exterminating its species during a three-year campaign. In 4017 BBY, Crusaders appeared in the Core Worlds, waging war against the inhabitants of Basilisk. Overrun, the Basiliskans seeded their own world with toxins to deny it to the Crusaders, who abandoned it but took numerous Lagartoz War Dragons, Basilisk warships, and war droids for their own use. Then, in 4002 BBY, the Crusaders ravaged the Deep Core world of Kuar, setting up camps there.

The Crusaders’ next target was the carbonite-rich Empress Teta system—but fate had other plans. In 3996 BBY the fallen Jedi Knight Ulic Qel-Droma challenged Mandalore the Indomitable to single combat at Kuar. Qel-Droma defeated the clan leader, who agreed to serve him and his Sith master, Exar Kun.

No one will ever know what the Crusaders’ plan was before Qel-Droma seized control of the Mandalorians’ destiny, but the goal of Qel-Droma and Kun was simple: destroy the Republic and its Jedi. Serving the Sith, Crusaders riding Basilisk war droids stormed the Republic shipyards at Foerost, then invaded Coruscant in their stolen warships.

Mandalore the Indomitable was certainly true to his word: He helped rescue Qel-Droma from Coruscant after Aleema Keto betrayed him, then led his Crusaders to Onderon, where Basilisks and Onderonian beast-riders clashed in the skies. A Republic fleet raced to Onderon’s rescue, forcing Mandalore the Indomitable into a risky retreat across an atmospheric bridge from Onderon to the moon Dxun.

The clan leader died in the attempt, but the Crusader who found his ceremonial mask (thus becoming the new Mandalore) was even more dangerous.

Mandalore the Ultimate had seen many battles and knew his fellow Mandalorian Crusaders were brave and skilled. But the new Taung clan leader wondered how much that mattered. His people remained a fractious society of restless adventure seekers, with little to show for their efforts but stolen technologies and a slice of space on the outskirts of the Republic.

There was a better way, and Mandalore the Ultimate was determined to find it. The defeated Crusaders returned to Mandalorian Space to learn that their leader had received a new vision on Shogun: From now on, non-Taungs who proved themselves in battle and upheld the Mandalorian warrior code were full members of the clans.

Moreover, the Crusaders would no longer simply pillage worlds and move on like some terrible storm. Now they would hold the territory they conquered, creating an industrial society based on warrior codes. Warriors would rule, supported by farmers, artisans, and manufacturers who accepted their place in the Mandalorian hierarchy, with slaves and those without honor below them.

Mandalore the Ultimate’s decision swelled the clans’ ranks with humans, Mandallians, Jakelians, and other Mandalorian vassals. Now the clan leader sent his Neo-Crusaders outward, conquering a swath of worlds between the Republic’s borders, pockets of Republic colonial space, and the Tion. The Neo-Crusaders found rich worlds for Mandalore’s growing empire, and billions of recruits: Hrakians, Elomin, Tiss’shar, Pho Ph’eahians, Togruta, Drackmarians, Thalassians, Nalroni, and Zygerrians.

The Sith War had left Republic authority largely theoretical beyond Centares; Mandalorian warships moved freely through the Tion, and began harassing the outlying worlds of the Hutts. Meanwhile, the Mandalorians were rapidly building warships at Breshig and Arda, utilizing vast caches of war matériel stolen during the Sith Wars from Foerost and Abhean.

In 3976 BBY a fleet of Neo-Crusader warships stormed Althir III, an industrialized world that gave Mandalore the Ultimate another productive planet for his war machine. Three years later the Mandalorians brutally subjugated Cathar, killing more than 90 percent of its population.

Alarmed, the Republic mobilized naval forces to guard Dxun, where clans of Mandalorians maintained a defiant stronghold, and to protect Taris and its neighbors along the Mandalorian Road. A motley if industrious city-world, Taris wasn’t a member of the Republic, but possessed extensive trade ties with the worlds of the Northern Dependencies. (It would be admitted to the Republic in 3966 BBY.) Spacers’ tales told of massive Mandalorian war fleets lurking in the dark beyond the Rim, but for a decade the Republic did little but watch and wait, even as Neo-Crusader raids imperiled worlds from Corsin to Azure.

Mandalore the Indomitable (John VanFleet)

In 3965 BBY the Mandalorians began prodding the Republic forces arrayed against them along the Taris front, skirmishing at Flashpoint Station and Suurja even as other Neo-Crusaders stepped up their raids into the Northern Dependencies. But battle wasn’t joined until 3963 BBY, when Mandalore the Ultimate’s forces launched a three-pronged attack. Neo-Crusaders broke through the Republic lines and invaded Taris; skirted the Republic border to attack Ithor, Ord Mantell, and the Zabrak worlds around Iridonia; and blasted the border world of Eres III.

The warnings of traders and scouts now proved true: The Mandalorians had huge numbers of captured warships along with ones of their own making. The core of the Mandalorian fleets was Kyramud battleships and Kandosii dreadnoughts—Basiliskan and Fenelar designs, respectively—but to that the Neo-Crusaders added Althiri frigates and corvettes, along with gunboats of their own design and a slew of variations on Basilisk war droids. Unprepared for such firepower, the Republic failed to hold the line. Serroco was scoured by nuclear fire, and Neo-Crusaders ravaged Nouane, whose elegant civilization and ancient mastery of statecraft epitomized all they despised.

All three offensives would fail, but it was a near thing. To galactic north, Republic forces counterattacked, aided by Zabrak military units, winning key victories at Iridonia and Ithor. That prevented the Mandalorians from executing a pincer movement against Coruscant, and allowed the Republic a corridor for reinforcing the Taris front. The Neo-Crusaders’ central thrust did substantial damage in the Northern Dependencies, but stalled because of a lucky break on the icy planet of Jebble: the mysterious destruction of a massive army of Mandalorians and slaves that was preparing for an assault on Alderaan. To galactic south, the Neo-Crusaders left Eres in ruins, raided Azure and Contruum, and linked up with Mandalorian units at Dxun. The Neo-Crusaders smashed a Republic task force at Commenor and ravaged Duro in 3962 BBY—but that was as far as they would get.

A significant number of Jedi disagreed sharply with the Jedi Council’s refusal to be drawn into the Mandalorian Wars, arguing that the Order was allowing misery and terror to spread unchecked. The leader of this movement is known to history as Revan, and his followers became known as the Revanchists. Together with the Jedi later known as Malak, Revan defied the Jedi Council, aiding targets of the Mandalorians’ campaigns and seeking the truth of the Neo-Crusaders’ conduct on worlds such as Althir and Cathar. Revan’s discovery of the atrocities committed against the Cathar failed to sway the Council, but the Order did look the other way as the Revanchists and other Jedi were appointed generals in the Republic military.

That military had not been idle. The great shipwrights of the Core and the Trailing Sectors had sensed war was coming and stockpiled raw materials, allowing them to turn out warships such as Centurion battle cruisers and Hammerhead cruisers. (The latter would prove one of the most popular warships in Republic history, still used by sector defense forces millennia later.) The Republic also benefited from a substantial technological breakthrough: a more efficient gravity-well projector that could be housed within the hull of a cruiser. The Republic’s Interdictor-class cruisers proved essential in hampering Mandalorian warships’ movements and trapping them in-system.

Revan and Malak helped prevent the Battle of Duro from becoming an even larger disaster, arriving with a fleet of Interdictors and preventing the Neo-Crusaders from escaping with massive stocks of matériel from Duro’s orbital shipyards. Bowing to the feelings of Republic citizens and eager to register his displeasure with the Jedi Council, Supreme Chancellor Tol Cressa named Revan commander of the Republic’s military forces.

Mandalore the Ultimate (Darren Tan)

Revan knew the Republic could win by following two tough courses of action: devoting its industrial might to defeating the Mandalorians, and being willing to pay a terrible price to do so. Often at immense cost, Revan pushed the Neo-Crusaders steadily back, until he cornered Mandalore the Ultimate at Malachor V in 3960 BBY—an encounter infamous among the Mandalorians as Ani’la Akaan, the Great Last Battle. There, Revan activated a Zabrak superweapon known as a mass-shadow generator. This device, a massively scaled-up version of an Interdictor’s gravity well, spawned a tremendous gravitational vortex that fractured Malachor V and destroyed much of the Mandalorian and Republic fleets assembled above that world. In the battle Revan killed Mandalore the Ultimate, ending the Mandalorian Wars at a stroke.

The Mandalorian warrior Canderous Ordo famously claimed that “as long as one Mandalorian lives, we will survive.” But the disaster at Malachor V marked a turning point in the clans’ history. After surrendering to the Republic, the disarmed clans retreated to their domain, rudderless without their leader. Some returned to their nomadic ways, but many others became mercenaries, dismissing the warrior codes that had failed to save them. Over the course of a generation Mandalorian society had mutated from a loose agglomeration of Taung warrior clans into a powerful, industrial civilization led by warriors of many species, only to be shaken by the terrible defeat of Ani’la Akaan.

After Malachor V the warrior codes were followed rigidly only within Mandalorian Space. Outside those borders, Mandalorians became infamous as bounty hunters, assassins, and mercenaries—to say nothing of pirates and slavers. They were respected as warriors, but mostly despised for their amorality and hunger for credits. The Mandalorians’ resentment of the Republic and the Jedi made them favored tools of the Sith, particularly in the Great War of 3681–3653 BBY, but they sometimes fought alongside the Jedi as well.

The century that began in 1100 BBY is remembered as one of the galaxy’s darkest: The Republic all but ceased to exist beyond the Core and Colonies, and the Candorian plague ravaged world after world. Systems and sectors that could do so built fleets as bulwarks against the chaos that was devouring the galaxy; those that couldn’t lived in terror of pirates and slavers—or floods of refugees from less fortunate worlds. The flame of galactic civilization was guttering and threatened to go out entirely.

Amid the horror, something unexpected happened. In 1058 BBY a mercenary named Aga Awaud returned to Mandalore to find that the Candorian plague had killed his family and most of his clan—and Mandalorian ships had to band together in caravans through Mandalorian Space, fearing raiders from the lawless surrounding sectors.

Awaud was appalled, and became the leader of the Return—a movement that urged Mandalorians to defend Mandalorian Space. In 1051 BBY he took the name Mandalore the Uniter. Under his leadership, Mandalorian Space not only survived the upheaval of the New Sith Wars but thrived, emerging as a regional industrial power and protector of neighboring systems and sectors. Mandalorian protection didn’t come cheap, and often proved coercive, but it was far better than the alternative.

After the Ruusan Reformations of 1000 BBY, a resurgent Republic sought to knit itself back together, reestablishing its institutions in the Outer Rim. The Mandalorians, at first seen as a welcome force for stability, increasingly seemed like a threat: They were taxing commerce along the Hydian Way and binding neighboring sectors with economic and defense pacts that were hard to refuse. And since Mandalorian Space wasn’t part of the Republic, the Mandalorians refused to abide by the post-Ruusan restrictions on sector defense forces.

Some clan leaders warned that Mandalore the Ultimate’s mistakes were being repeated: The Mandalorian way of life might endure so long as the clans wandered the space lanes, but as a people the Mandalorians had no hope of winning a fight with the Republic. They argued that Mandalore should join the Republic, immediately becoming one of its most powerful and influential sectors. But the peacemakers were shouted down: If Mandalorians weren’t warriors, they weren’t Mandalorians at all.

In 738 BBY the Republic created a task force made up of Judicial Forces and units drawn from Planetary Security Forces in the Expansion Region, with the Jedi Order coordinating the war effort. The Mandalorian Excision was brief but overwhelming: Key Mandalorian worlds such as Fenel, Ordo, Concord Dawn, and Mandalore itself were subjected to devastating bombardment, with swathes of those worlds still desolate in Imperial times. Mandalorian Space was occupied and disarmed, with a caretaker government created from elements of the failed peace movement.

The occupation would last for decades, and create a new schism in Mandalorian society. From the caretaker government emerged the so-called New Mandalorians, who bitterly resented the Republic but saw no hope in fighting it, and so renounced the warrior codes in favor of peace and neutrality. The New Mandalorians held most positions of power, and rebuilt Mandalore’s industrial base over the next few centuries. Some unrepentant mercenaries and warriors were exiled to the moon Concordia, while others dispersed throughout the galaxy, resuming the Mandalorians’ ancient trade as blasters-for-hire. The Mandalores of the post-Excision era were drawn from their ranks, though their authority was recognized by neither the New Mandalorians nor the sector government.

In the last century before the Battle of Yavin, two new Mandalorian movements arose. The mercenary Jaster Mereel, who became Mandalore in 60 BBY, sought to reinstitute the warrior codes. His True Mandalorians were opposed by mercenaries who argued that the way to restore the clans’ honor was to topple the hated New Mandalorians and repay the Republic’s savagery in kind. This group became known as the Death Watch.

Few Mandalorian clans were united on the subject: The New Mandalorians, True Mandalorians, and Death Watch could all claim Ordos, Vizslas, Kryzes, Fetts, Awauds, and Tenaus as supporters. The True Mandalorians were decimated at Galidraan in 44 BBY, while Death Watch allied itself with the Separatists during the Clone Wars, scheming to provoke a new Republic offensive that would eliminate their enemies. And as a final irony, Jango Fett—who claimed to be one of the last True Mandalorians—became the template for the Republic’s clone army and supervised the clones’ training. The Republic that had fought the Mandalorians so many times over the millennia now depended on an army of them for its defense.

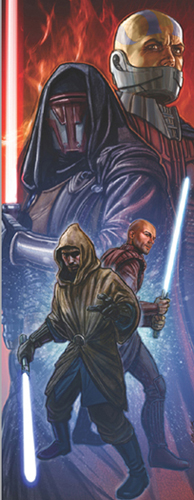

Revan and Malak (Jason Palmer)

The “Army of Light” is legendary as the last great Jedi host of the ancient Republic, mustered by Lord Hoth in the closing campaigns of the New Sith Wars. But the origins of this unique fighting force began to take shape several centuries before.

By the beginning of the New Sith Wars, the Republic had endured centuries of turmoil. Sith and Separatist forces had gained control of the Rim and pushed Coreward, while corrupt megacorps had shaken off all but the most self-interested ties to the government, and many civilized systems had simply closed their borders. Only Jedi Knights had the will and skill to defend the helpless.

These “Jedi Lords” began their careers as knights on quests to defend abandoned worlds from slavery and exploitation. Gradually they came to hold political authority over systems and entire sectors, and became hereditary barons and kings. The Jedi domains were islands of peace and justice, where honorable rulers fought to keep the Sith at bay, attracted other brave Jedi to their banners, and sired sons and daughters who followed their parents in the way of the Force. Eventually, even the office of Supreme Chancellor and the rule of Coruscant itself were ceded to a line of Jedi Masters.

While post-Ruusan historians and Imperial propagandists emphasized the anarchy of these centuries, they also marked the last great age of the Jedi Knights, and many systems prospered under their rule. When Lord Hoth decided to take the offensive against the Sith in 1010 BBY, he gathered Jedi Lords and their bands of knights from across the galaxy, a movement that swelled until the last Grand Council of the Order declared all the Jedi baronies united as the Army of Light, commanded by Lord Hoth bearing the ancient title of Seneschal.

The core of this army consisted of seven legions led by the greatest Jedi Lords, who followed Hoth directly into battle, often piloting agile starfighters and speeder bikes. They were supported by Republic units that preferred Jedi leadership to the orders of the Admiralty, and by additional forces such as the private army of the half-Bothan Valenthyne Farfalla. Farfalla commanded one of the largest fighting companies of Force-wielders ever seen—a personal retinue of one hundred knights and esquires, and a feudal following of two hundred more. Farfalla’s knights were equipped not with the usual starfighters, but with remarkable timber-framed space gunships, which had deflector shield skins backed by the strong and flexible wood of the wroshyr tree found on the Wookiee homeworld Kashyyyk.

Lord Hoth led his army to Ruusan in 1001 BBY, becoming enmeshed in a disaster. Casualties mounted, and orbital supply lines were blocked. Morale collapsed. Local levies, organized and armed with whatever was available, were thrown into battle, and for the final push every camp follower still able to stand was given a weapon and a place in the line. The final battle saw the Sith destroyed by the machinations of one of their own, Darth Bane, along with Lord Hoth and most of his knights. Victory was claimed by bureaucratic factions in the Jedi Order and the Republic—beings who opposed the entire concept of Jedi Lords, and had been appalled by the feudal ethos of the Grand Council.

Veterans of the Army of Light were ignored by the reformed Jedi Order, which was embarrassed both by their politics and by the tragedy of Ruusan. The few surviving Jedi Lords returned to their castles and took care of their men, calmly ignoring the orders of the Jedi on Coruscant, and maintained a wary detachment from the Republic for centuries. Even under the New Republic, the remaining Corellian Jedi and Teepo Paladins retained distinct identities, based on their descent from these ancient heroes.

Valenthyne Farfalla aboard his flagship, Fairwind (Chris Scalf)

WAR PORTRAIT: LORD HOTH

Lord Hoth never thought of himself as a general. In his youth he dreamed only of wielding a lightsaber; as he grew old, he saw himself as just a teacher and warrior. But he was the man on whose broad shoulders the responsibility of destroying the Sith came to rest.

Rohlan of Kaal was heir to a minor line of Jedi Lords from Yushan sector, but still in his teens when he left the citadel of his ancestors to win renown as the Knight of Hoth—the Jedi hero who freed the Corellian Trade Spine from Sith pirates. In his mid-twenties, after the Republic committed troops to consolidate his gains, he traveled to Coruscant and became Master Hoth, the respected battlemaster of the Jedi Temple—a warrior grown weary of battle, training a new generation of apprentices how to fight with a lightsaber.

Hoth’s imposing physical presence and skill with a blade made him a hero for his trainees, but the tales of his exploits barely reached the marble corridors trod by the Temple’s masters, and his simple loyalty to the Order clashed with the subtle theory and diplomacy that pervaded the senior ranks. The Jedi Council’s great hope for the future was a slim, sophisticated young commoner from the capital named Skere Kaan, an expert in battle meditation, fleet command, and economic policy. Kaan had developed a radical theory about the anarchy that had shaken civilization for a thousand years: He blamed the Republic and the Jedi Order.

The Council, believing that they could moderate these daring arguments into a practical reform policy, rewarded Kaan with a Jedi Master’s rank. But in 1010 BBY Kaan grew impatient with their interference and left the Order, leading a group of like-minded Jedi Knights in a dramatic schism. Calling themselves the Brotherhood, they announced their intention to conquer the fragmented Sith enclaves as a prelude to reforming the Republic—and within months Kaan had slain the worst of the Sith warlords and forced the rest to beg for peace. The Jedi Order sent its enthusiastic congratulations, but Kaan was busy remaking his conquests into a weapon to use against them. Within a year, he had assumed the throne of a new Sith Empire and declared war on the Republic.

Without waiting for the Jedi Council’s next mistake, Hoth gathered his followers from the Temple and his veteran Jedi Knights from the Javin Marches. Adding allies from Corellia, Cularin, and Kamparas, he became Lord Hoth, the Seneschal of the Army of Light. For ten years he and his men methodically liberated Sith strongholds on the Outer Rim, while avoiding a direct confrontation with Kaan.

Military historians now regard Hoth’s war as an act of great generalship—a clear-minded campaign to weaken the enemy on the flanks while hardening and strengthening his own troops for a decisive blow against their isolated center. By the time of Ruusan, the Army of Light was larger and better trained than it had ever been, but Hoth’s focus on the regional warlords also allowed Kaan to consolidate his hold on the Brotherhood and strike deep into the Core. It was Kaan’s conquest of the Brentaal junction that forced Hoth to make his decisive move at Ruusan, where he led the Army of Light into a long, grim stalemate in the mud and gunfire of the Seven Battles. Darth Bane, in a plot to destroy his fellow Sith so he could establish his Rule of Two, convinced the Brotherhood to use a thought bomb against the Army of Light. The detonation of the bomb destroyed the Brotherhood of the Sith along with Lord Hoth and the majority of the Army of Light. Lord Berethon, one of only two Jedi Lords to survive the battle, said that the Army of Light had grown too big for Lord Hoth to lead: “From first to last, his instincts were those of a Knight, not a general.” Hoth’s best moments, like the Third Battle of Ruusan, were essentially small-unit tactics implemented on a grand scale, while his worst mistakes were either attempts to stand back and direct his forces on the map like an Academy-trained field marshal or harshly rational misjudgments, like the forced conscription of Jedi children to prevent their kidnapping by the Sith. Ultimately, Hoth’s successes and his failures all suggest the same basic truth: One Jedi hero can do more good than an entire professional army.

Rohlan of Kaal dueling Sith pirates on Hoth (John VanFleet)

INTERDICTOR TECHNOLOGY

A key to controlling space is the ability to force passing starships out of hyperspace. Every starship has fail-safes intended to force a reversion to realspace if a mass shadow is detected that’s too large to be avoided with a small course correction. Since the earliest days of faster-than-light travel, pirates and military commanders have tried to exploit this for strategic purposes.

The Argaian pirates led by Xer, father of Xim the Despot, intercepted ships by towing ice asteroids into the narrow hyperspace lanes through the Indrexu Spiral, and similar tactics are still used today. Another tactic is to scatter bits of ice, dust, or metal chaff (popularly known as decant dust) across a hyperspace lane.

But such brute-force tactics are generally inefficient and pose navigational problems for those who use them, too. A better tactic is to simulate large mass shadows or dangerous hyperspace eddies. Mass mines—which project the signatures of much larger objects—are one alternative, though they are tedious to deploy and recover afterward. Another option is a quantum field generator, which disrupts the null field generator that keeps ships stable in their passage through hyperspace. But quantum field generators have immense power demands and can often damage a starfleet’s own null field units.

During the Mandalorian Wars of the 3900s BBY, Zabrak engineers came up with a new tactic: projecting a simulated gravity well into realspace, either to prevent starships from escaping into hyperspace or to drag them out of it. Starship-based interdictor fields proved an ideal solution: They were mobile, could be activated or deactivated as needed, and didn’t leave space lanes needing to be cleaned up. After its introduction, interdictor technology sparked a technological spiral of advances and countermeasures. The relatively weak interdictors of the Mandalorian Wars were soon rendered ineffective by better hyperdrive sensor suites and multiphase null field units, and interdictor technology became a sidelight for millennia until the Clone Wars inspired aggressive new research.

The Empire built on the Republic’s technological breakthroughs, and the bulbous gravity-well generators of Interdictor cruisers soon became familiar sights. These new projectors were powerful enough to catch almost any starship, but required the drive systems and spaceframe of a large capital ship. The protruding projectors also limited the available positions for weapons emplacements and launch bays, making interdictors underpowered as front-line warships. Only battleships were big enough to carry effective interdictor systems without serious penalties in cost or weaponry.

The arms race would continue: The Bakuran military introduced hyperwave inertial momentum sustainers, popularly known as HIMS generators, which produced hyperspace bubbles that could push interdictor fields aside. First introduced at the Battle of Centerpoint Station in 18 ABY, HIMS generators were used by the New Republic and the Galactic Alliance against the Yuuzhan Vong’s dovin basals.

In 1000 BBY, following the defeat of the Sith at Ruusan, Tarsus Valorum set out to heal a shattered galaxy and rebuild its institutions by making them more democratic and mutually supporting. The Ruusan Reformations were an unprecedented experiment: a voluntary dismantling of central authority over economic, political, and military power.

To make the Senate more governable, Valorum con-solidated its millions of sectors into 1,024 regional sectors, each with its own Senator, though political necessity forced him to carve out exemptions for powerful worlds in the Core and Colonies, and to extend the right of representation to the galaxy’s functional constituencies—ancient institutions with considerable economic power.

Though not formally bound by the Ruusan Reformations, the Jedi Order made fundamental changes as well. The Jedi gave up the bulk of their forces, from ground vehicles to warships and starfighters, and became part of the Judicial Department, reinforcing the fact that they answered to the Senate and were ideally counselors and advisers, not warriors. To decrease the chance that far-flung academies might stumble into dangerous explorations of the Force, Jedi training was consolidated in the Temple on Coruscant. And Jedi trainees would now be taken into the Order as infants, before they could be exposed to the temptations of the material world.

But for a war-weary galaxy, the most extraordinary measures of the Ruusan Reformations were the ones that abolished the Republic’s armed forces.

The standing military was reorganized as the Judicial Forces, a relatively small assemblage of task forces and rapid-response fleets, intended to patrol the frontier and respond to crises. The Senate could authorize the Judicial Forces to requisition military units from systems and sectors, and the Supreme Chancellor could appoint Governor-Generals to coordinate military action with the Senator of a troubled sector. In the absence of a major crisis, the Planetary Security Forces—for fourteen millennia little more than an auxiliary of the Republic Navy—would be expected to keep the peace.

Determined to curb the Republic’s regional rivalries and restrict sector fleets to defensive operations, Valorum ordered limits on fleet sizes and armament. Cruisers more than six hundred meters long were limited to Class Five hyperdrives by modern standards, and their navicomputers were restricted to local charts. Judicial Inspectors were given wide-ranging powers to enforce these regulations, and “bluecoats” with datapads became common sights aboard military vessels and in depots. Cruisers below the six-hundred-meter limit emerged as the workhorses of the sector fleets and the Judicial Forces alike, and remained the backbone of many military organizations long after the Yuuzhan Vong invasion.

The Reformations were less popular in the Rim world sectors. Decommissioned navy cruisers, frigates, and corvettes were assigned to these Sector Forces, and some wealthy sectors sold off capital ships in excess of their defense allowances to their poorer brethren. (Others, fearing a resumption of war, stripped their warships of weapons and key systems and mothballed them.) But the outlying sectors were last in line for the naval spoils. Exemptions to the Ruusan limits were allowed for frontier sectors and dangerous areas of the galaxy, but their Senators had to struggle with Judicial bureaucrats and Senate committees to win these allowances—and often couldn’t afford to take advantage of them.

While Rim sectors struggled to police their worlds with creaky, undersized capital ships, wealthy industrial sectors built giant cruisers on a scale not seen for millennia, seeking to create impregnable defenses and impress their neighbors. Such sectors took advantage of loopholes in the Reformations: For example, systems and planets that had retained the right to direct Senate representation received additional military allowances. The new battleships were denied transgalactic capabilities and were hamstrung by armament limits, but they still made for formidable fleets—many of them concentrated in the regions of the galaxy that faced the fewest threats to law and order. Elsewhere, intergalactic organizations sought to flout the rules by building giant transports that could be quickly adapted into warships.

Yet another big loophole was an exemption granted to starship manufacturers allowing them to create prototype warships and experimental variants of existing models and classes. The exemption was intended to encourage sectors to establish their own shipyards and to ensure continued technological innovation. But it led to shipwrights creating “demonstration fleets” made up of variations on warship designs and leasing effective control of them to sectors that could afford them. In the Republic’s final centuries, the shipwright exemption and armament limits encouraged modular warship manufacturing, allowing rapid alterations to ships’ armament, capabilities, and functions. By then wealthy sectors were awash in warships, with their fleets’ numbers swelled by “loans” from starship manufacturers.