CHAPTER TWO

The President’s Library

ARCHITECT. INVENTOR. SCIENTIST. SCHOLAR. A READER OF FIVE LANguages. These attributes seemingly just scratch the surface when describing Thomas Jefferson. Many presidents have had a range of eclectic interests, but none so broad and deep. Well before the term was first coined, he was a true Renaissance man. Perhaps another president, John F. Kennedy, put it best when he welcomed forty-nine Nobel laureates to a 1962 dinner: “I think this is the most extraordinary collection of talent, of human knowledge, that has ever been gathered at the White House—with the possible exception of when Thomas Jefferson dined alone.”1

It should come as no surprise, then, that Jefferson surrounded himself with like-minded brilliance. Indeed, his administration featured a constellation of talent, notably Secretary of State James Madison—known as the “Father of the Constitution” and the author of the Bill of Rights, Albert Gallatin as treasury secretary, and Henry Dearborn, who served as secretary of war.

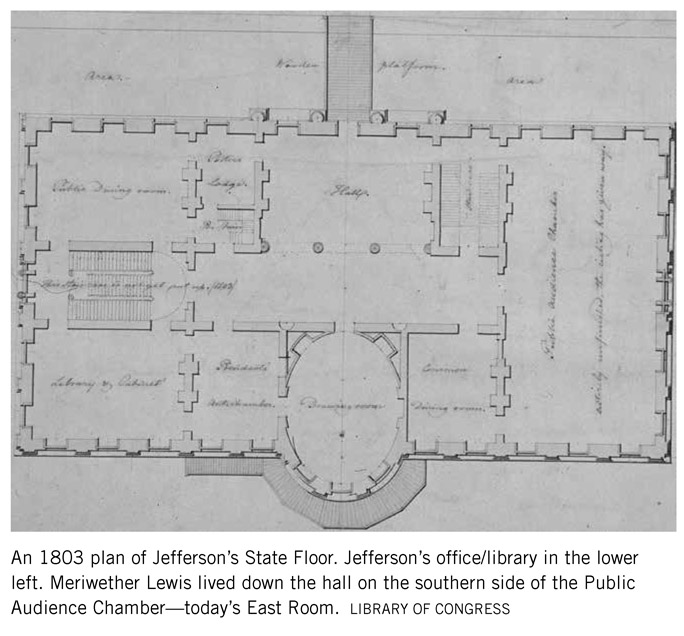

Yet in terms of sheer impact on American history, perhaps the most important person our third president would invite into his administration was a somewhat shy but tough and resourceful young man—just twenty-seven years old—with no Cabinet rank at all. He would be closer to Jefferson than anyone, both literally and figuratively, living in the mansion’s biggest room—the East Room—all by himself, in a temporary space built from nothing more than a cheap wooden room divider and heavy sailcloth. It was his relationship with the president, whose own office was just down the hall, that would change the young nation forever. His name was Meriwether Lewis.

For a man who fought so hard to win the presidency—losing in 1796 to his Federalist rival John Adams but exacting his revenge four years later—Thomas Jefferson was in no hurry to live in the President’s House itself. He spent the first fifteen days of his presidency living in Conrad & McMunn’s tavern on Capitol Hill (on the present site of the Longworth House Office Building), living simply in two rooms: one for personal use and the other for business. He took his meals in the dining room, sitting at a communal table alongside other guests.2

Jefferson’s nonchalance about moving into the President’s House was rooted in his republican preference for simplicity, and an accompanying disdain for anything that reeked of strong, central authority—a central philosophy of the now-vanquished Adams. Even in its partially completed state, Jefferson thought the mansion too imposing, too fancy, and too monarch-like for his taste, incompatible with a man who had authored America’s Declaration of Independence from an overbearing English king.

In short, “The place was a monument to the Federalist point of view and Thomas Jefferson counted it important to cut the palace down to size.”3 But the architect and designer in Jefferson would get the best of him; he had to admit that he was intrigued by the mansion, its symbolism, and the promise it conveyed. During the design competition for it a decade earlier, Jefferson—then George Washington’s secretary of state—had even submitted an anonymous entry, one of at least six known submissions before Thomas Hoban’s winning entry was selected.4 5

But in 1801, with Adams preparing to leave the mansion after a mere four months, Jefferson realized he would be the first president of the United States to live in the mansion for an extended period. He also knew that the home, with its vast interior spaces and grounds, remained quite unfinished and raw. It was an irresistible opportunity for the president-architect to truly shape both the mansion and its surroundings as he saw fit.

Jefferson inspected the President’s House within a week of being inaugurated, believed to be the first time he had ever set foot inside. On entering he would discover a building that, while far from complete, was much further along than it was when Adams encountered the pungent aroma of wet plaster, lead paint, and varnish just four months earlier.6 He likely agreed that the mansion was as a newspaper had described it: “big enough for two emperors, one pope and the grand lama in the bargain.”7 In January, Hoban had completed the second of three staircases, this one near the entrance hall on the north side of the mansion. But the third had yet to be built; Hoban planned to install it in the west end of the transverse hall. In its place, the new president found a hole, illuminated during portions of the afternoon by shafts of light that streamed in through a “great half-round lunette window.”8

Jefferson saw that the mansion’s biggest room, the vast Public Audience Chamber—used by Abigail Adams to hang dripping wet laundry9—still lacked plaster walls and a ceiling. And there were no water closets, just an outhouse known as a privy. Aside from the fact that rain and snow made it uncomfortable, it was undignified for the president of the United States—particularly a fastidious man like Jefferson—to be seen scurrying back and forth between his home and an outdoor commode. One of his first acts as president, therefore, was to have two proper water closets installed on the upper floor of the mansion where he would live, one on the western end of the house, the other on the eastern end. An order went to a “Mr. Dorsey” on Third Street in Philadelphia for “Water closets . . . of superior construction, which are prepared so as to be cleansed constantly by a Pipe throwing Water through them at command from a reservoir above.”10 By “above,” Jefferson meant the attic, where the reservoirs, made of tin, collected rainwater.11

Even so, Jefferson’s water closets lacked running water, a luxury that wouldn’t appear until the administration of Andrew Jackson nearly three decades later.12 Jefferson also had coal-burning fixtures installed in fireplaces; he knew that coal burned more slowly than the wood Adams relied on, making it more efficient and freeing up servants for other tasks.13

Curiously, given his belief that the President’s House was too grandiose, the president expanded it. Borrowing a page from Monticello, his mountaintop plantation near Charlottesville, Virginia, Jefferson ordered one-story extensions added to the President’s House, on the east and west sides of the mansion, respectively; these became known, appropriately enough, as the East and West Wings. They would be used, among other things, for servants’ quarters, woodsheds, and a wine cellar.14 Drawings, most in Jefferson’s hand, indicate a larger desire to extend the mansion’s wings to federal buildings on each side of it.15

And while Adams considered the south side of the President’s House to be its principal entrance, Jefferson didn’t. He cared little for the aesthetically unappealing wooden stairs and platform leading into the mansion and ordered them torn down. He considered the north door, framed by four Ionic columns and topped by a Palladian window surrounded by beautiful stone carvings of flowers, leaves, acorns, ribbons, and bows, to be more suitable.16 When visiting dignitaries arrived through this door and entered the Entrance Hall, the room directly before them (today’s Blue Room) would be a drawing room, just as Hoban had intended. Jefferson may have lost the competition to design the President’s House to Hoban, but there can be little doubt that as he settled in, the architect of Monticello came to increasingly admire his rival’s magnificent creation, even as he improved upon it and made it his own.

A widower since the death of his wife, Martha, in 1782, Jefferson recognized the need for someone who could help run the President’s House. And he knew exactly whom he wanted. On February 23, 1801, nine days before he was to be sworn in, the president-elect wrote Meriwether Lewis a letter, saying he needed a secretary “not only to aid in the private concerns of the household, but also to contribute to the mass of information which it is interesting for the administration to acquire.”17

Lewis was an Army captain who also hailed from Virginia. Within days of learning that he had been elected president, Jefferson sent a letter to General James Wilkinson, commanding general of the US Army, asking him to locate Lewis. The president-elect said he sought Lewis because of “a personal acquaintance with him, owing from his being of my neighborhood.”18

By “neighborhood” Jefferson meant the central Piedmont region of Virginia, where Lewis was born in 1774, some ten miles west of Monticello. There were blood ties as well: Two of Jefferson’s siblings had married into the Lewis family, and Lewis’s uncle, Nicholas, helped run Jefferson’s farms while he served as ambassador to France between 1785 and 1789.19

In an 1804 letter to a former secretary, Jefferson described the broad portfolio that Lewis had been given—astonishing in retrospect for such a young man whom Jefferson knew only casually and had never worked with before:

The office is more in the nature of that of an Aid [sic] de camp, than a mere Secretary. The writing is not considerable, because I write my own letters & copy them in a press. The care of our company, execution of some commissions in the town occasionally, messages to Congress, occasional conferences and explanations with particular members, with the offices, & inhabitants of the place here it cannot so well be done in writing, constitute the chief business.20

But Jefferson had another reason for wanting Lewis. The young Army officer possessed “a knolege [sic] of the Western country, of the army & it’s [sic] situation,” which Jefferson considered invaluable.21 22 The “Western” country in 1801 generally extended to the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers and the western edge of Pennsylvania. He predicted that Lewis, who would be provided with a servant and a horse, would find the job an “easier office” than being in the Army, and that it “would make you know & be known to characters of influence in the affairs of our country, and give you the advantage of their wisdom.” The president-elect sweetened the pot further, assuring Lewis that he could also retain his officer’s rank and be eligible for further promotion.23

A chance to escape a dreary Army base and work alongside the president of the United States? Unable to resist such an offer, Lewis accepted immediately and “with pleasure.”24

Jefferson, wanting the trusted Virginian nearby at all times, invited Lewis to live in the President’s House itself. He ordered carpenters to build two rooms in the vast Public Audience Chamber for Lewis’s personal use. At the time, it was being used for storage, and Lewis soon had, on the southern end of the room, an office and a smaller room for a bedchamber.25 There was more than enough room for Lewis in the cavernous space, which measured 2,844 square feet and featured ceilings that soared twenty-two feet.

Then, as now, proximity is power in Washington: The closer one is to the president, the more powerful the person is perceived to be, and likely is. Meriwether Lewis quickly became known as one of the most influential people in the Jefferson administration, a man who literally was just down the hall from the president’s office.

That the president’s office itself was on the ground floor was another change from Adams’s short-lived tenure in the mansion. It was the room Adams had used for levees (receptions for visitors) and today is the State Dining Room. But for Thomas Jefferson it was his office—and thus for eight years the focal point of his presidency. “Tall and generously proportioned, the office had fireplaces east and west, and was flooded with daylight through tall south and west windows.” Jefferson presumably appreciated the unimpeded view out the southern window, which offered a sweeping vista down the Potomac River all the way to the port of Alexandria.26

A private man, Jefferson granted relatively few people access to his inner sanctum—a privilege largely reserved for his Cabinet and for Lewis. There was at least one outsider though, who gradually worked her way into this exclusive club—Margaret Bayard Smith, a prominent journalist. The careful notes she took offer wonderful insight into President Jefferson’s private office: “In the centre was a long table, with drawers on each side . . . around the walls were maps, globes, charts, &c.”27

The tables were covered with green baize (a cloth or felt), and there were library steps for reaching tall bookshelves. The presidential chairs were painted black and gold, and the mahogany floor was largely bare.28 There was one contrast with the rest of the mansion. Although he had replaced log-burning fireplaces elsewhere, he kept two of them in his private workspace. The office as a whole, which measured thirty-eight feet by twenty feet, with an eighteen-foot ceiling, was referred to as the “cabinet” or “library.”29 Next to this was a small sitting room, and beyond this, in an easterly direction, was the oval drawing room—today known as the Blue Room. It was here that the most prominent piece of art in the President’s House—then as now—was first hung: Gilbert Stuart’s larger-than-life portrait of George Washington.30

Jefferson often mixed business and pleasure. One drawer in his “library” was stuffed with gardening tools; there were plants and flowers—mostly roses and geraniums—on one window sill, and suspended from above was a birdcage. Jefferson owned a mockingbird named Dick and let it fly around the room. Smith says Dick “was the constant companion of his solitary and studious hours,” and often perched on Jefferson’s shoulder or ate “food from his lips.”31 It is easy to visualize the president, engrossed in work, surrounded by greenery, warmed by two crackling log fires, and serenaded by the warble of his beloved bird.

Although he enjoyed socializing, Jefferson lived a rather isolated existence in the President’s House. His solitude was such that he extended an open invitation to Treasury Secretary Gallatin and his wife to have dinner each night. It would be “a real favor,” he said.32 But for health reasons (“the city is rather sickly”), Gallatin told the president, they moved farther away, to Capitol Hill. Regardless, the president—who ate just two meals a day—rarely dined alone; Lewis, naturally, was a frequent companion.

That Jefferson and his young protégé enjoyed each other’s good fellowship was obvious to many observers. In addition to being a regular at the presidential dinner table, Lewis often joined Jefferson at church; the seat to the president’s left was always reserved for him.

In general, the two men lived “like two mice in a church,” Jefferson once said.33

It is not that Jefferson was lonely or unhappy. “We find this a very agreeable country residence,” he noted. “Good society, and enough of it, and free from the noise, the heat, the stench, and the bustle of a close built town.”34 Comfortable in his own skin, surrounded by his beloved books, plants, and his singing mockingbird, he delighted in solitude and the opportunity it gave him to read and think.

Visitors to Monticello these days are usually surprised, when they see Thomas Jefferson’s grave, that his headstone—written by the man himself—only mentions three of his many towering achievements: “Author of the Declaration of American Independence, Of the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom and Father of the University of Virginia.”

It may seem incredible to some that Jefferson deliberately chose to omit the eight years he served as president of the United States. But this should not be overly surprising given his fundamental aversion to what the presidency itself represented—a strong, single authority figure at the heart of the government. But it can be argued that another of Jefferson’s accomplishments—and certainly the greatest of his presidency—should have been included: his audacious purchase, in 1803, of the Louisiana Territory from Napoleon and his decision to have Lewis explore it.

Even before the United States was able to purchase the territory, Jefferson had dreamed of acquiring at least a portion of it, and talked about it frequently with Lewis. During the summer of 1802, in the president’s office, Lewis’s office down the hall, and at Monticello, they conversed “about little else” other than Alexander Mackenzie, a Scottish explorer who had traveled over much of the territory, and written about it in a book called Voyages from Montreal, on the River St. Lawrence, Through the Continent of North America, to the Frozen Pacific Ocean. Unwieldy title aside, and despite the fact that it was probably ghostwritten, the book was a useful rendering of much of the Louisiana Territory itself, and the president and Lewis “devoured it.”35

But Mackenzie’s mission seemed insufficient to the two men. The Scotsman was only in search of little more than an economically efficient route for the fur trade. He took few notes on flora and fauna, potential mineral deposits, or Indian life. Lewis, the rugged outdoorsman and Army officer, knowledgeable about botany and wildlife, knew he could do better. As for Jefferson, he worried that the British—or someone else—would carve a commercial path to the West Coast ahead of America; both he and Lewis were determined to prevent this from happening.36

At some point in the latter half of 1802—there is no documentation on exactly when or where—the president told Lewis he was being given command of an expedition to the Pacific. The order was as presumptuous as it was bold, given that America at that point neither owned the Louisiana Territory nor had any prospect of buying it. Jefferson evidently consulted no one else about the wisdom or folly of such an undertaking and gave no consideration to anyone other than Lewis for the mission; Lewis was going to do it, and that was all there was to it.

Why Lewis? Jefferson later explained:

It was impossible to find a character who to a compleat [sic] science in botany, natural history, mineralogy & astronomy, joined the firmness of constitution & character, prudence, habits adapted to the woods, & a familiarity with the Indian manners & character, requisite for this undertaking. All the latter qualifications Capt. Lewis has.37

Jefferson knew this because Lewis had access to the president’s extensive collection of books and maps at both Monticello and in the president’s office in the mansion; the two talked incessantly about them. Some of the president’s advisors failed to share Jefferson’s confidence in Lewis, considering him uneducated and a bit of a hothead. But knowing of Lewis’s voracious reading habits, inquisitiveness, and eagerness to learn, Jefferson knew better. History would ultimately validate the president’s judgment.38

Jefferson’s intense interest in the Louisiana Territory was not limited to botany, wildlife, or astronomy. He also saw the territory, controlled by a European power sitting on America’s doorstep, in national security terms. When he entered office in 1801, the area was controlled by Spain, a fading colonial power that had no substantive military presence in North America. But Britain had commercial interests in upper Louisiana; the Russians, connected to the continent through their vast holdings in Alaska, did business near the mouth of the Columbia River, and the French, who once owned Louisiana, had expressed renewed interest in the territory.

The presence of any of these powers on America’s doorstep, Jefferson believed, was an unacceptable security and commercial threat. It was imperative that the United States be the unchallenged master of the North American continent, which in his mind was meant to be an “Empire of Liberty,” settled by a people “speaking the same language, governed in similar forms and by similar laws.”39

It was Napoleon’s France that soon emerged as Jefferson’s principal worry. Shortly after taking office, he learned of a treaty the French had made with Spain, returning control of the Louisiana Territory to Paris. The president was alarmed: “There is on the globe one single spot, the possessor of which is our natural and habitual enemy. It is New Orleans, through which the produce of three-eighths of our territory must pass to enter market.” Jefferson told a British diplomat that “the occupation of this country by France” would likely lead to eventual hostilities. “The day that France takes possession of New Orleans . . . we must marry ourselves to the British fleet and nation.”40

The president dispatched fellow Virginian James Monroe, the former governor of the commonwealth, to Paris, who, along with Ambassador to France Robert Livingston, was to inquire about buying New Orleans and Western Florida (which stretched along the Gulf Coast of what are today Alabama and Mississippi).41 At some point soon after, Jefferson informed Lewis of the possibility that the United States might take ownership of this territory, and instructed him to prepare a journey of exploration.

As it happened, Napoleon, focused on the possibility of war with England, saw Louisiana as a far-off and expensive burden that he could not afford to maintain. On April 11, 1803, he told his finance minister that he was renouncing the territory. That same day the French foreign minister, Talleyrand, stunned Monroe and Livingston by asking if the United States wanted to buy not just New Orleans and West Florida but the entire Louisiana Territory itself—all 828,000 square miles of it. It was the size of the entire United States itself.42

On April 30, the two Americans, on their own, negotiated a treaty to purchase it for $15 million.43 It would not be possible to name another real estate transaction of such consequence that was concluded so smoothly and quickly. It is a rich irony that Jefferson, a man who in principle opposed strong executive authority, would oversee and conclude such a stupendous deal on his own. Federalists in New England who disliked Jefferson were particularly critical; but even their recriminations withered away in the face of the enormous benefit the territory would bring to the nation at large.

Word of the deal reached the President’s House on the evening of July 3, a Sunday.44 Reading the letter from Monroe and Livingston, Jefferson was as stunned as he was thrilled, though the dispatch lacked one key detail—the price. Jefferson had nothing to worry about: The $15 million worked out to about three cents per acre. It was a steal. “This removes from us the greatest source of danger to our peace,” he wrote.45 A friend, General Horatio Gates, wrote that it was “the greatest and most beneficial event that has taken place since the Declaration of Independence.”46 Meriwether Lewis prepared to depart immediately.

The president wasted no time in announcing the stupendous news. The American people would first hear of the Louisiana Purchase the very next day—the Fourth of July—twenty-seven years to the day after Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence was adopted by the Continental Congress, formally severing ties between the thirteen colonies and Great Britain. Now the public learned that the United States had just doubled in size, expanding across the Mississippi River, north into the Dakota Territory, and up and down the spine of the Continental Divide. All told, the Louisiana Purchase encompassed what would become all or part of fifteen future states. It was a stunning achievement for both Jefferson and the young nation.

It made for a particularly glorious Fourth. Jefferson appeared on the north steps of the President’s House for all to see, and then invited the public inside to shake hands. He then joined a party in progress, probably in the Oval Reception Room (today’s Blue Room), where the Louisiana news was the main topic of excitement. Ironically, one man wasn’t there. Meriwether Lewis had slipped away, probably out the south entrance. He would leave the next day for St. Louis to join his handpicked colleague, William Clark.47 Together they would journey into the Louisiana Territory—and the history books—chronicling, with their “Corps of Discovery,” one of America’s greatest adventures.

The president wrote his departed aide, describing “the journey which you are about to undertake for the discovery of the course and source of the Mississippi, and of the most convenient water communication from thence to the Pacific.”48 Their voyage would represent the culmination of a long-standing dream of Jefferson’s, the high-water mark of his presidency, and one of the most monumental chapters in American history. As he dispatched the letter, one wonders whether the president felt a twinge of envy.