CHAPTER TWELVE

The West Wing

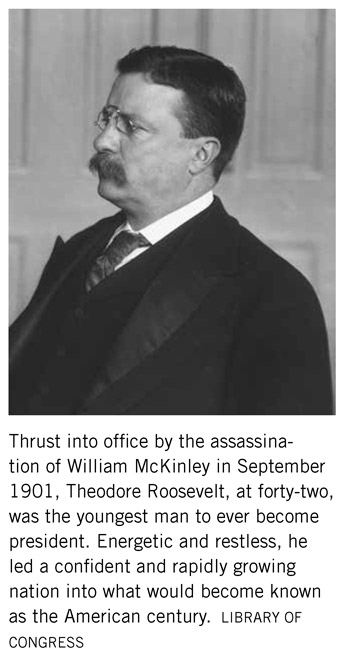

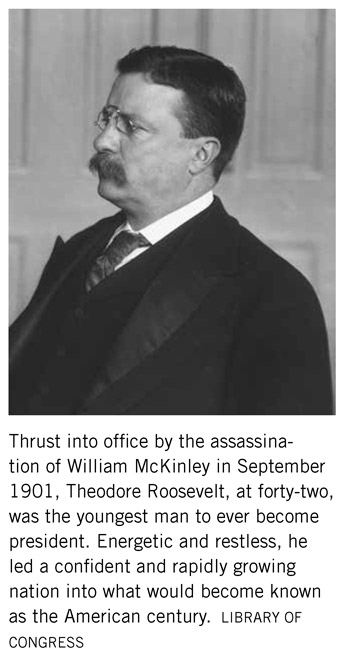

HOURS BEFORE HIS ASSASSINATION on April 14, 1865, Abraham Lincoln signed legislation creating the United States Secret Service. It wouldn’t have saved him that night, nor would it have helped James Garfield sixteen years later. That’s because the original mission of the Secret Service was rather narrow: to stop currency counterfeiting. It took the assassination of a third president, William McKinley, for Congress to request, in 1901, that the Secret Service expand its portfolio to protect the president of the United States.1 In 1902 two agents were assigned to the White House full-time.2 They had their work cut out for them. Their protectee, Theodore Roosevelt, just forty-two when he took over for McKinley, was the youngest—and perhaps most energetic person ever to become president.

If ever there was a man born for his era, it was TR. As the curtain rose on the twentieth century, the United States had quietly, and rather quickly, become a great world power. Straddling a continent, protected by the buffer of two vast oceans, rich in natural resources, industrializing rapidly and not the least bit hesitant about embracing the future, America and its bespectacled new leader could be defined in exactly the same way: forward-thinking, brash, and supremely confident.

Roosevelt quickly and with a sense of urgency made his mark on everything from business (breaking up monopolies like John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil and E. H. Harriman’s Northern Trust Railroad) and foreign policy (building the Panama Canal and brokering an end to a war between Russia and Japan—for which he won the Nobel Peace Prize) to conservation (protecting vast swaths of land and expanding America’s national park system).

But when he moved in and looked around at his new home and place of work, Theodore Roosevelt was embarrassed. The Executive Mansion, as it was officially known, was run-down, decrepit, and cramped. If America was the vibrant, powerful center of the New World, TR reasoned, then its most visible symbol must reflect such grandeur.

Accordingly, Roosevelt embarked upon a massive remodeling of the mansion. He had two goals: Return it to its Federal roots, which would entail the removal of decades’ worth of heavy, dark Victorian-era decor and design, and an expansion of presidential workspace. From Adams to McKinley, presidents had always worked and lived in the mansion itself. Now Roosevelt wanted some separation between work and home. Thus was born the West Wing, today the principal workspace of the president of the United States.

Before all that though—and even before the flowers from William McKinley’s funeral began to wilt—Roosevelt took one step that symbolized that a new man was in charge: He officially did away with the name “Executive Mansion,” formally renaming the residence what millions of Americans had long called the imposing building at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. The name was reflected in the clean, crisp elegance of new stationery he ordered, with paper and envelopes:

THE WHITE HOUSE.3

Theodore Roosevelt’s desire to expand the White House and separate its living quarters from its workspace was driven by two principal factors. The US government was growing, not just in size but complexity; the head of the executive branch simply needed more room. But there were personal reasons too. The new president and his wife, Edith Carow Roosevelt, had six young children ranging in age from nearly four to sixteen. The First Family also had what amounted to a mini-zoo: countless dogs, birds, guinea pigs, snakes, rabbits, badgers—even a small bear named Jonathan Edwards.

Once, when Archie Roosevelt, the president and first lady’s fifth child, was sick, brothers Kermit and Quentin brought his beloved pony—Algonquin—up to see him, carefully guiding the horse into the White House elevator.4 It was a big, rambunctious family, happy, outgoing and active—the biggest First Family to live in the mansion since the presidency of John Tyler.5 The eight rooms and two bathrooms set aside for personal use on the second floor simply weren’t enough.6 One bathroom, connected to the president’s bedroom, was used by the president and Mrs. Roosevelt, leaving one for everyone else, including any visitors.7 Clearly, something had to be done.

Presidents had come and gone over the decades, yet the interior of the White House always seemed to be described in creaky, tumbledown terms. Charles Dickens thought so in the 1840s, sagging floors had to be propped up in the Lincoln era, and a few years later there was serious discussion about tearing the mansion down entirely.

A new century had arrived, but old problems persisted. Floors still sagged. The wooden staircase leading to the second floor was clearly worn, and the new First Family was undoubtedly bothered by the “curly wallpaper and wainscots jaundiced with fifty years of tobacco spit.”8 Carpets in a hideous mustard color, peeling plaster, and exposed and wooden pipes that made “flatulent noises in wet weather” were also incompatible with the president’s desire for a majestic home in which to live.9

Although fairly new to Washington, Roosevelt’s legislative skills became apparent in 1902, when he got Congress to approve $343,945 to begin repairs of the mansion and another $131,500 for new furnishings.10 Another $65,196 was approved for a new, separate office building for the president.11 The Roosevelts picked a New York architectural firm, McKim, Mead & White, for the project, with day-to-day work supervised by a principal of the firm, Charles McKim.

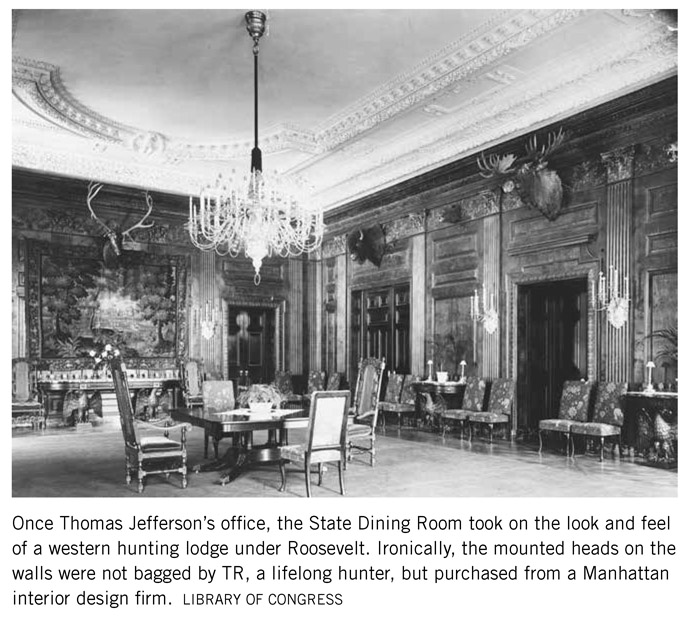

The desire for grandeur aside, the president established several goals for the renovation of the White House. In addition to making the mansion structurally safe, he wanted the presidential workspace relocated, which would benefit both the growing executive branch and his family’s personal needs. He wanted more efficient movement of large crowds at White House events. He wanted the State Dining Room—once Thomas Jefferson’s office—expanded, and he wanted all the ugly appendages of technological progress (pipes, electric cords, etc.) removed or hidden away. All of this, Roosevelt insisted, was to be done in such a way that contributed to the overall image of the White House as a stately place in which to live, work, and entertain—a place that would make the American people proud. And it had to conform with the style and vision as expressed by the mansion’s original architects more than a century earlier.12 The president wanted it finished by December, in time for the holiday parties he and the first lady planned to give. McKim had five months.13

Where could the presidential offices go? The original plan presented to George Washington, the only president who would never live there, called for the construction of a White House five times bigger than the mansion we know today. This proved impractical, and a more modest structure—still the largest building in the United States at the time—was built. In the ensuing century, the area around the White House had been built up: The Treasury Building lay just east of the mansion, while the State, War, and Navy Building (today known as the Eisenhower Executive Office Building) stood to the west. Even if Roosevelt had wanted to dramatically expand the White House, big federal buildings on either side brought physical limits to the task.

But the famous colonnades extending in both directions from the mansion, designed by Benjamin Latrobe and Thomas Jefferson, presented Roosevelt and architect McKim with some intriguing possibilities to do something more modest, such as build in a southerly direction. Standing in the way were the massive greenhouses installed by prior administrations.

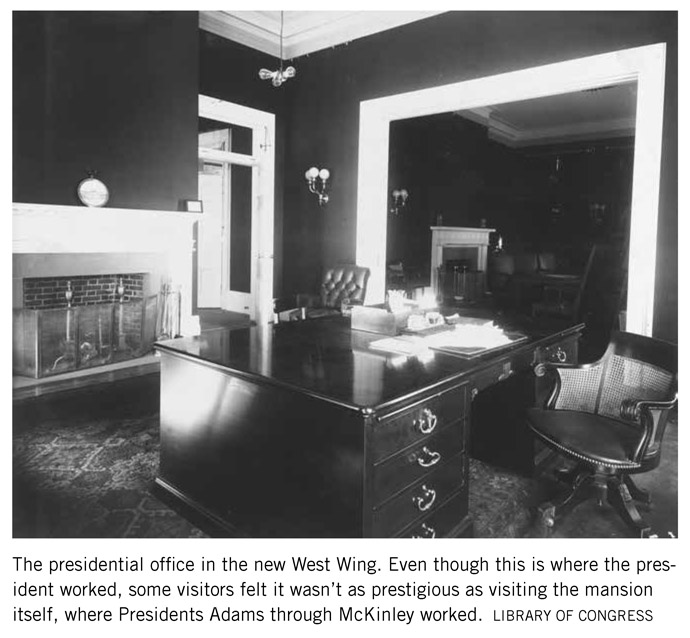

TR, the activist president and man of action that he was, was neither shy about expressing his desires nor sentimental toward parts of the mansion that he disdained. “Smash the glass houses,” he bellowed,14 and down came the conservatories that had been part of the White House since the days of James Buchanan nearly half a century before. In their place, McKim built a “temporary Executive Office” building,15 soon to be known as the West Wing. It was square, with long windows on the ground floor and short windows on the floor above, made to resemble Federal-style architecture from the mid-nineteenth century. It included a Cabinet Room; telegraph room; rooms for secretaries, stenographers, and the press; a filing room; a reception room; and closets in the basement.16

A final room, of course, was the highlight: Roosevelt’s office, dubbed the “President’s Room.” It would be in the southeast corner of the new building, overlooking the South Lawn. The room was square, with sliding doors opening into the Cabinet Room, which Roosevelt wound up using for both meetings and entertaining. McKim and his men worked so fast that the building was finished in late September.17 It took another two weeks for paint to dry.

When Roosevelt eventually moved in, it meant the end of what had been the century-long tradition of the president of the United States living and working under the same roof. In the beginning, many visitors considered the Executive Office Building a step down in prestige from the nearby mansion, even though the president himself now worked there.18

Adjacent to this had been stables and a greenhouse known for the roses it produced. These were torn down and a garden—dubbed the Colonial Garden—was planted. Running parallel to the West Colonnade, it consisted of several triangular and oval-shaped areas where boxwoods, roses, and lilies flourished.19 A decade later, another new first lady, Ellen Wilson, would rename it the Rose Garden.

As the West Wing rose, so did the East Wing. Added to the end of Jefferson’s graceful colonnade, it would serve as an entry point for visitors—as it does today. A long covered entryway accommodated carriages (and soon, cars), and there was a long cloakroom for visitors to deposit their belongings before moving on to social events in the East Room and elsewhere. The construction of the East Wing accomplished Roosevelt’s goal of having visitors arrive and move about the mansion’s public areas more efficiently and comfortably.

As for the mansion itself, old floors, stained and scratched, were yanked up. The smell of plaster that had first greeted John Adams returned as walls were redone and painted. On the ground floor the entrance hall just off the North Portico had featured an attractive screen of iron and glass that had stood since the administration of Franklin Pierce (1853–1857). At the behest of Chester Arthur (1881–1885), Louis Tiffany made it even more spectacular with the installation of colored glass. When light struck the glass, it projected a blaze of color on the hall’s cream walls.20 Beautiful as many considered this to be, the president ordered the screen removed.21

Adjacent to the entrance hall, Roosevelt and McKim decided that the mansion’s biggest chamber—the East Room—would no longer be an “over-ornamented salon, loaded down with crude decorations.” William McKinley’s potted plants were tossed, as was much of the furniture, which one influential critic sniffed was “crude in the extreme, with poorly designed frames and no taste in the color or materials of the covers.”22

Electric lighting, which had first come to the White House in 1891 when Benjamin Harrison was president, was expanded. Three giant Bohemian glass chandeliers were wired and hung; the three chandeliers that had hung since the Grant years were sent to Capitol Hill.23 The entire State Floor—the Green, Blue, and Red Rooms—was also wired, as was the State Dining Room at the far end of the long Cross Hall. The First Family’s living quarters on the second floor and the modern new East and West Wings would be illuminated by electricity as well.24

It was in the State Dining Room that Roosevelt’s personal taste became most apparent. Straying from the Federal style that he wanted for the rest of the mansion, he approved a country-house look, featuring heavy oak paneling and massive tapestries on the walls. The president also had animal heads mounted, including a moose over the fireplace. Ironically, these trophies weren’t bagged by the president—a lifelong hunter—but purchased from a Manhattan interior design firm.25 This veritable zoo might not have conformed with George Washington and architect James Hoban’s original vision for the White House. But Thomas Jefferson had also displayed stuffed animals, so Roosevelt could have claimed that his homage to the past was accurate enough.26

The renovation was a circus. “The house is torn to pieces . . .” McKim wrote in July, “bedlam let loose does not compare with it.”27 At one point portions of the great mansion were reduced to their bones—just walls and support beams. Standing in the basement, McKim could gaze up into the Blue Room on the ground floor and, one floor above that, into Abraham Lincoln’s old office, a “gawking, hollow shell, with fluttering wallpaper shreds dancing in the summer breezes.”28

The tight schedule also threatened the president’s desire that the original character and heritage of the White House be respected to the utmost. McKim knew little of the White House’s history and didn’t particularly care;29 his concern was getting the job done on time. This resulted in decisions that initially seemed wise only to be seen later as folly. One of the best examples: McKim thought the problem of sagging floors could be solved by laying steel beams down and bolting them to brick walls. But it never occurred to McKim that the walls themselves weren’t strong enough to hold the steel beams securely.30 It was errors like this that contributed to the near collapse of the White House years later during the Truman administration.31

While McKim and his small army of workers toiled frantically, the First Family had wisely decamped. The president moved in June to a house a block away at 22 Jackson Place on Lafayette Square,32 while his family went to the Roosevelt’s home on Long Island. Roosevelt himself would join them in early July.

Thus Theodore Roosevelt became the third president to live somewhere other than the White House as it was rebuilt. But James Madison and James Monroe were forced to live elsewhere following the destruction of the White House in 1814—Roosevelt’s departure was thoroughly voluntary. The First Family would return on November 4th, promptly throwing a dinner party for friends. When they retired that night, the second floor was theirs alone, and it felt huge. There were more bedrooms, and each had its own bathroom, shimmering with white ceramic tile and nickel fixtures.33

On the eastern end of the floor, the former Cabinet Room was now a presidential study; just outside was the grand staircase, which had been relocated from the west end of the hall near the presidential bedroom. Its removal left a large space that became a living room for the Roosevelts—and for First Families that followed.34 The president was thrilled. “You will be delighted with the White House,” he wrote son Kermit. “The changes have improved it more than you can imagine.”35

The presidential bedroom itself—which was in the old Prince of Wales Room overlooking the North Lawn36—featured a piece of furniture that was special to Roosevelt: the famous Lincoln bed. Like millions of Americans, the twenty-sixth president revered the sixteenth. One of Roosevelt’s first moves in the White House was to get rid of the brass beds in the presidential bedroom and replace them with the “Lincoln bed.”37 It’s unknown whether Roosevelt knew Lincoln had likely never slept in it, but TR certainly wished for some of the Great Emancipator’s luster to rub off on him. Perhaps Roosevelt did know that the room in which he slept was also used for Lincoln’s autopsy and embalming in 1865.

Abraham Lincoln and Theodore Roosevelt could not have come from more different backgrounds. Lincoln, the humble, shy man, born in a log cabin with dirt floors, a man who grew up in poverty and received no formal education and encountered numerous setbacks on his way to the White House; how Roosevelt—born into wealth and privilege, educated at Harvard, a man whose rise up the ladder was swift and unimpeded—wished to emulate him! Roosevelt told friends that Lincoln was “my great hero,” a man who meant “more to me than any other of our public men.” Throughout his nearly eight-year presidency, Roosevelt kept a portrait of the Great Emancipator in his office for inspiration. “I look up to that picture, and I do as I believe Lincoln would have done,” he said.38 39

“The Restoration,” as it was called in 1902,40 complete, President and Mrs. Roosevelt opened their sparkling new home to the public for the first time on New Year’s Day 1903. Thousands lined up, and the president, energetic and in jaunty spirits as usual, shook every hand. Reviews were universally good. “Visitors noticed the dignified, tasteful, yet simpler and starker interiors that gave the rooms a more spacious look and reflected the nation’s larger role in international affairs,”41 while others called it intelligent and refined. The president and first lady were immensely pleased. Writing Congress to thank it for the money used on the massive project, Roosevelt wrote:

The White House, which had become disfigured by incongruence has now been restored to what it was planned to be by Washington. In making the restorations the utmost care has been exercised to come as near as possible to the early plans . . . the White House is the property of the nation, and so far as it is compatible with living there and it should be kept as it originally was, for the same reasons that we keep Mount Vernon as it originally was. The stately simplicity of the architecture is an expression of the character of the period in which it was built, and is in accord with the purposes it was designed to serve. It is a good thing to preserve such buildings as historic monuments which keep alive our sense of continuity with the nation’s past.42

The White House under Theodore Roosevelt became a showcase, reflecting, he believed, America’s prominent new position on the world stage. Great Britain was still regarded as the preeminent global power as the century began, an empire on which the sun never set. But to Roosevelt, that sun was just beginning to rise on the American empire; it was a glorious time to be an American president. He was always in a hurry, and when he was governor of New York, TR was “a young man who was eager to reform the whole world between sunrise and sunset,”43 according to President Benjamin Harrison. That description was no less accurate when Roosevelt became president himself. He possessed an endless amount of exuberance, and made no effort to hide it. Journalist Lincoln Steffens observed, in the aftermath of the McKinley assassination:

His offices were crowded with people, mostly reformers, all day long, and the President did his work among them with little privacy and much rejoicing. He strode triumphant around among us, talking and shaking hands, dictating and signing letters and laughing. Washington, and the whole country, was in mourning, and no doubt the President felt he should hold himself down; he didn’t, he tried to, but his joy showed in every word and movement.44

All of this was meticulously noted by the press, which, under Roosevelt, became more intertwined with the presidency than ever before. In a decision that future presidents probably wish he hadn’t taken, he spotted a group of reporters standing in the rain one chilly day and invited them inside. Scribes have shadowed presidents ever since, tracking their every move and utterance.45

Perhaps Roosevelt invited reporters in because he didn’t want them freezing to death. But it’s likely he had a more calculated reason. By the turn of the century, newspapers had become increasingly sophisticated and influential. Radio was still a generation away; any politician wanting to reach a mass audience knew that newspapers were the only way to go. William McKinley invited reporters to work on tables in the second floor hallway of the White House, but wouldn’t actually speak to them. Not only did Roosevelt invite reporters in that cold damp day, he gave them an actual room—just off the new Executive Office Building’s entrance—in which to work.46 It was the first true White House Press Room.

Unlike the taciturn McKinley, Theodore Roosevelt was a chatterbox. When he had something to say (which was quite often), he would pick up the telephone and personally summon them to his office.47 Dozens would scamper to the second floor or to the West Wing to hear what was on his mind. On topics both consequential and mundane, the president’s approach was generally the same: He was informal, and often spoke to the gathered scribes “as though they were close friends.”48 Those “friends” didn’t seem to know (or care, perhaps) that they were being seduced by TR, a master show-man, for they “almost idolized the man”49 and reveled in their access to him. Invariably, the end result was one that many a future president could only dream of: a press that reported things just as the president preferred.50 His incessant ability to talk, talk, talk lay waste to one of his most famous sayings: “Speak softly and carry a big stick!”

The love fest continued when the president traveled, often on a larger scale than was possible in the crowded White House. Whenever Roosevelt hopped on a train, railroad companies would add on an entire car for reporters; sometimes there were as many as 150 of them. Sometimes wealthy friends of the president—with private cars of their own—decided they wanted to go along too. Before long the entourage was so big that instead of the presidential car and press car being attached to a regular passenger train, there were now “presidential trains” themselves.51 George Cortelyou, the super-efficient secretary who modernized McKinley’s press operation and had been kept on by Roosevelt, organized trips with the precision of a Swiss watchmaker, giving all travelers a detailed hour-by-hour itinerary. At the end of the twentieth century, it would require a small army to do the job that Cortelyou did almost single-handedly.

Beyond changing the White House, Theodore Roosevelt changed the way in which Americans saw the presidency itself. It was seen, more than ever, as a center of great and unmatched power, power wielded by just one central authority. Not since Andrew Jackson—who loved to wrap himself up in his trademark blue cape and make dramatic entrances in his own lustrous new East Room—had the citizenry seen a president with such a flair for showmanship. Indeed, “his symbolic stature was more powerful in its time than Jackson’s or Lincoln’s had been” in theirs.52

The staid, stuffy Victorian era was no more; the White House was now occupied by a man who was determined to liven things up—and to have things his way. It was all quite calculated: “To the formal setting he gave a common touch with humor and incongruous behavior, turning the simplest occasion into a theatrical production.”53 In his home, in his country, on the world stage, Theodore Roosevelt was determined to be at the center of everything, and he was.