“SILENCE!” ADMIRAL FAUCET BELLOWED IN the darkness. “Don’t panic, men! Nor women and children, either.”

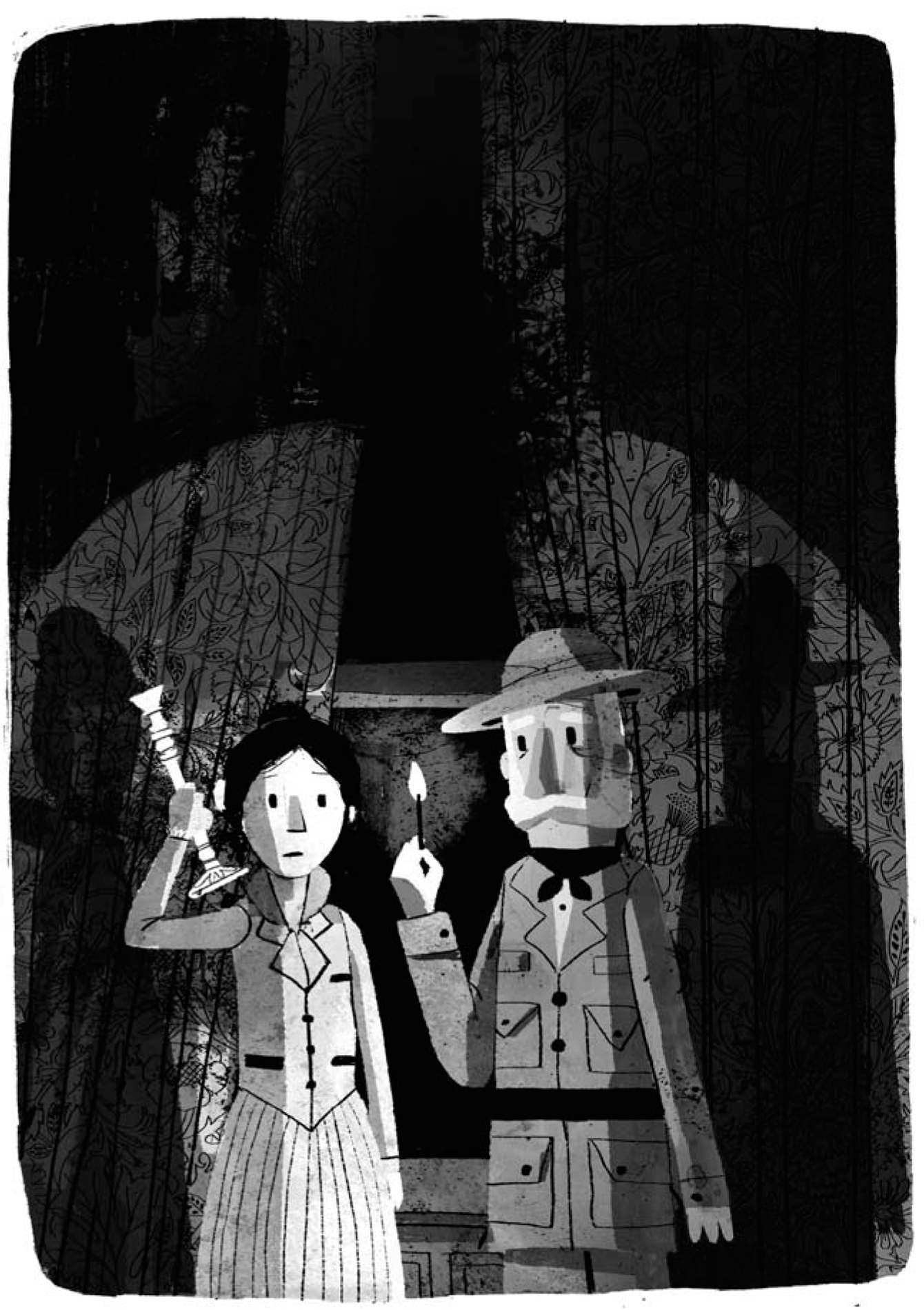

He struck a match on the bottom of his boot and circled it ’round the room like a tiny searchlight, revealing each person in turn. The children crouched on their chairs, alert and ready to pounce. Penelope brandished a candlestick like a weapon. (At the Swanburne Academy, the girls had once put on a famous play that begins with the appearance of a ghost and ends with a dramatic duel involving a poison-tipped foil, a perfectly thrilling scene in which no fewer than four of the leading characters meet very gruesome ends indeed. Clearly, the experience had left its mark, as well as some residual skill at swordplay.) Lady Constance whimpered from beneath the dining-room table. And Lord Fredrick Ashton was hanging on to his mother, who did not seem to mind at all.

Penelope brandished a candlestick like a weapon.

Nevahwoooooooooo!

Bang! Bang!

It was the wind, howling mournfully through the open windows while the shutters banged back and forth. Throwing down her candlestick, and for the second time that day, Penelope ran to the windows and wrestled them closed. “The latch seems to have snapped,” she said. “But this will do until a locksmith can be summoned.” Quick as a wink, she removed a hairpin and used it to secure the broken latch.

Once she was done, the admiral relit the candles. “Well done, governess. You’d be a useful person to have along on a safari. After all, an explorer must be resourceful! Why, once when I was in Africa, I sailed down the Nile in a raft made of nothing but lashed-together reeds and a sail woven out of palm leaves. What’s for dessert?”

Oddly, the brief scare of the snuffed-out candles and howling wind seemed to break the spell of gloom cast by the Widow Ashton’s gruesome tales. Or perhaps it was the prospect of dessert that lifted everyone’s spirits; in any case, the entire party moved to the parlor for after-dinner sweets and drinks. A sticky bread pudding was brought in. There was warm honeyed milk for the children, and coffee and sweet Madeira wine for the adults.

After the pudding was served, and with only a tiny nudge from his governess, Beowulf stood up. “I have a gift for you, your gracious widowhood,” he announced to the Widow Ashton. From behind his back he produced the picture he had drawn earlier, which had been carefully rolled up and concealed in Alexander’s spyglass case until the right moment came to present it. The Widow Ashton fumbled for her pince-nez as the admiral took the drawing in both hands and gave an admiring whistle.

“That’s my Bertha, all right. Did you do this yourself? Why, you’re a regular Audubon.”

“Audawho?” Beowulf asked, puzzled.

“John James Audubon drew birds that were dead and stuffed. But I’d wager Bertha was moving at a fast clip when you spotted her, and even so, you caught her likeness very well. That makes you better than Audubon, laddybuck!”

Beowulf grinned from ear to ear and seemed to grow taller on the spot.

Lord Fredrick put down his coffee cup. “I’m feeling rather stuffed myself. What say we go to my study, Faucet? Let the ladies play whist, or stitch advice onto pillows, or whatever it is they do when we’re not around.”

“It’s your house, Ashton; I’ll do whatever you like. Say, lad—Beowulf, is it?—if it’s birds you want to draw, come to your uncle Freddy’s study. There’s enough taxidermy in there to keep you scribbling for a year.” Standing, the admiral turned to Alexander. “You come along, too, young man. You look old enough to try a cigar, eh?”

Penelope jumped to her feet so quickly she nearly spilled her pudding. “You are so kind to include them, sir, but it is long past the children’s bedtime—and I fear the cigar smoke would upset their tummies after such a rich meal.” In fact, cigar smoke was the least of Penelope’s worries. The one time she and the children had wandered by accident into Lord Fredrick’s study, the sight of his vast collection of taxidermy had upset more than just their tummies. All those dead animals, in lifelike poses, with their sightless, staring glass eyes—surely the boys would remember?

“I want to go,” said Beowulf, slipping off his chair to the ground. “If Audubon draws stuffed birds, I draw stuffed birds.”

“Me too, Admiral Laddybuck.” Alexander jumped to his feet and assumed the wide, bow-legged stance of a sea captain that he often used when playing pirates.

Lord Fredrick shrugged from the doorway. “Bring ’em along, I don’t care. As long as I get my port, what?”

The admiral turned and clicked his heels at the boys. “You heard your uncle Freddy. Follow me, men! Brave explorers are we, off to Parts Unknown! Hup, hup, hup, hup.”

“But, Admiral—it is already past ten o’clock….”

As a rule, brave explorers do not have worried governesses mouthing objections to their adventures in Parts Unknown. Alexander and Beowulf gave only the briefest apologetic parting glance at Penelope, who felt utterly helpless to stop them from going with the admiral and Lord Fredrick.

“But what about Cassiopeia?” she called after them, for she knew the little girl would be hurt not to be included in the admiral’s invitation, had she known about it. Luckily, she did not. The exhausted child was facedown in her pudding, fast asleep. In any case, the boys were already gone. Penelope returned to her chair as if in slow motion; when she folded her hands in her lap, her knuckles turned white.

“Well, now it is just us ladies, left to enjoy ourselves in peace. Isn’t that nice?” Lady Constance did not sound nearly as cheerful as her words suggested; in fact, she sounded quite cross. “Dear Mother Ashton, shall I ring for a deck of cards, as Fredrick suggested?”

“No cards for me,” said the Widow Ashton, rising. “The hour is late, and I have too much on my mind. Look at sweet Cassagurr! She is worn-out, poor thing, and needs a mother’s tender care. I shall go to bed, too, and leave you to tuck her in.”

“As I do every single night, without fail,” Lady Constance declared. “And sing lullabies, too. La la laaaaa, la la laaaaa—”

“You might want to rinse her off first; she looks a bit sticky.” The widow paused. “But I suppose even the stickiest pudding is better than a tar pit. Good night.”

ONCE HER MOTHER-IN-LAW WAS OUT of the room, Lady Constance would have nothing to do with the messy, sleepy child. It was up to Penelope to wash the pudding off Cassiopeia’s face and hands with a napkin dipped in water, and carry her all the way upstairs to the nursery. There she changed the groggy girl into a nightgown and rolled her into her bed. “Nevahwoo,” Cassiopeia mumbled, drifting back to sleep.

Penelope was tired, too, and worried about the boys. She tried to calm herself with reading, but she could not concentrate on the story, and the words swam upon the page. When Albert suggested to Edith-Anne Pevington, “Let’s be friends,” Penelope read, “Gruesome ends.” When Edith-Anne announced that Rainbow needed a “new bridle and bit,” Penelope could have sworn it said “medicinal tar pit.”

Frustrated, she shut the book. She wished—oh, what did she wish? She wished her friend Simon Harley-Dickinson were here to talk things over with. Simon was the perfectly nice young playwright whom Penelope had met in London. They had shared some memorable adventures, and the children had become quite fond of him as well. It was Simon who taught Alexander how to use the sextant and had even sent him his spare one as a gift. He had a knack for navigation, a loyal heart, and a keen interest in getting to the bottom of things. And there was something about his company that made Penelope feel a bit fluttery on the inside, as if a flock of warblers on the wing had taken a detour through her tummy.

It was just like how Edith-Anne Pevington felt about her new acquaintance Albert, except Albert was fictional, of course, and Simon, with his mop of wavy brown hair and that darling gleam of genius in his eyes, was wonderfully, winsomely real. But he was far away, too; too far to readily ask for advice.

“‘The plot thickens’—that is what Simon would say,” Penelope thought, chewing her lip. “A strange, wolflike illness that comes on the full moon; a family history of meeting gruesome ends…Madame Ionesco, the Gypsy fortune-teller we met in London, said something about the children being under a curse. Could the Ashtons be under a curse, too? It would be an unlikely coincidence if they were, but I suppose that for anyone to be under a curse is highly unlikely to begin with. I do wish I could speak to Simon! No doubt he would find it all very inspiring and get loads of plots out of it, enough for a whole trunk full of plays. I shall have to write him a letter tomorrow”—and here she yawned, for it was well past her bedtime as well—“asking him to interpret the widow’s strange tales.”

Cuckoo. Cuckoo. Cuckoo—

The clock struck the quarter hour. Penelope awoke with a start. She had nodded off in her chair; it was now fifteen minutes past eleven o’clock. Cassiopeia snored softly from her bed (it sounded as if the poor child might still have some pudding up her nose), but the boys’ beds were empty.

The sight of those smooth, unrumpled blankets struck fear in Penelope’s heart. “Agatha Swanburne would march to Lord Fredrick’s study right now and insist on putting the boys straight to bed,” she thought, and started for the door, but then she had second thoughts. “Or perhaps she would say something philosophical, like ‘A watched clock never chimes,’ and fix herself a cup of tea.” Alexander and Beowulf were in their own house, after all, under the supervision of two adult gentlemen, one of whom was their legal guardian. What was she so worried about? The boys were probably having a rip-roaring time, and being welcomed into the company of men was surely good for them, even if it did leave Penelope sitting helplessly, waiting for their return.

She sat once more in her chair, closed her eyes, and tried to imagine Alexander and Beowulf as they might grow up as Lord Fredrick’s wards, at home in the world of proper English gentlemen: a world of private clubs and taxidermy-filled studies, brandy snifters and expensive cigars, games of billiards and talk of the stock exchange. And, of course, hunting expeditions. She tried, but she could not do it. Such a future for the Incorrigible boys seemed entirely improbable in her eyes, but she did not know what other, different fate to picture for them, either.

“One thing is certain: They will not be boys forever,” she thought, remembering Mrs. Clarke’s comment about the too-short trousers. And Lord Fredrick Ashton was a wealthy and powerful man. If he began treating the Incorrigibles as if they were his own natural-born children, as his mother seemed to think he should, wouldn’t that be lucky for them?

Perhaps it would, but whether it was gooden luck or baden remained to be seen. “And there is something peculiar about the Ashtons,” Penelope thought as sleepiness descended upon her again like a fog, “with their howling fits and gruesome ends. I hope the day does not come when the children think they would have been better off”—she yawned—“living in the woods….”

CUCKOO. CUCKOO. CUCKOO. Cuckoo—

“Hup, hup, hup, hup!”

“Shhhh!”

It was quarter past midnight when the boys finally marched back to the nursery. They were much too excited to stop talking but too giddy with exhaustion to make any sense.

“A-hunting we will go!”

“To Bertha we will go! Hup, hup, hup!”

Penelope roused at the sound of their “hup, hup, hup.” Groggy with sleep, she struggled to understand what they were obviously eager to tell her.

“We are going hunting!”

“For Bertha!”

“We are in charge of tracking. No dogs. Dogs would bite.”

“We are good at navigating and good at bird-watching. We can track and not bite. Hup, hup, hup!”

In bits and pieces, and all while shushing and reminding them to put on their nightshirts for bed and not wake their sister in the process, Penelope came to understand that the two boys planned to accompany Lord Fredrick and the admiral on an expedition into the woods of Ashton Place, with the goal of finding Bertha, catching her, and bringing her back to an ostrich-proof enclosure that the admiral had already designed and that would be constructed behind the barn over the next few days.

“Brave explorers are we!”

“Unmapped Territories! Parts Unknown!”

“This ostrich-gathering expedition sounds interesting, and perhaps even educational,” Penelope whispered, picking up the trail of clothes the weary boys had left on the floor, “but you are not going anywhere until you get a good night’s sleep. We shall discuss it further in the morning.” She sniffed at the dirty clothes and made a face. Everything smelled like cigar smoke.

“No point catching Bertha if there’s no place to put her. That’s what the admiral says.” Alexander climbed onto his bed and slipped under the light summer blankets. “She’d only run away again.”

“Perhaps Bertha is not as excited about ostrich racing as the admiral is,” Penelope replied, tucking him in. “Good night, Alexander. Good night, Beowulf.”

“Nets, Alawoo,” Beowulf mumbled to his brother. “We should bring nets.”

“Must make list and pack,” Alexander replied dreamily. “I’ll bring my sextant.”

“I’ll bring pencils.”

“And a tent.”

“Ostrich treats to lure her home.”

“And guns, too. Hup, hup, hup!”

Penelope was so startled she forgot to whisper. “Guns? Why would you need guns? I thought the plan was to catch Bertha, not shoot her.”

“Berthahwoo,” Cassiopeia grumbled from her bed, turning over and burying herself deeper under the covers.

“Guns are not for Bertha.” Alexander snuggled his head into his pillow and closed his eyes. “Guns only to shoot wild animals. Uncle Freddy says we must be careful in the forest.”

“Yes,” said Beowulf with a yawn. “There are dangerous animals in the woods. That’s what Uncle Freddy says.”

Ten seconds later, they were both asleep.

TIRED AS SHE WAS, THE bleary-eyed governess tossed and turned for the rest of the night, dreaming of spooky forests full of dangerous beasts and flocks of scowling, black-feathered ostriches who cried “Nevermore!” as they raced in circles ’round her, and dinner platters full of tasty-looking roast pheasants that suddenly came back to life and started to peck—and peck—and peck—

“That is quite enough of that,” she resolved the third time she awoke from this same unsettling dream. As she rose and dressed, she racked her brain trying to figure out what sort of expedition the gentlemen really had in mind, and whether it was a good idea for the boys to go along, and if not, how she might prevent it.

“I am only the governess, after all.” She stabbed the hairpins into her bun with a great deal more ferocity than usual. “Lord Fredrick is their guardian. How am I to overrule him, if it comes to that?”

And then, of course, there was this business with the guns. She sat in the small rocking chair by her bedside and rocked in time to the ticking clock. “The boys said the guns are for ‘dangerous animals’ only. But which are the dangerous animals, and which are the safe ones?” The question was impossible to answer, for even a warbler is dangerous to an earthworm, and (as Penelope had recently learned) a mild-mannered pheasant could be murderous if provoked. A studious child who could spell “circumnavigate” and had almost mastered long division might be deadly to a tasty-looking pigeon, if the child happened to have been raised by wolves and had gone too long without a snack.

And a pack of slavering, sharp-toothed wolves might not prove dangerous at all to a trio of human cubs abandoned in the woods, if the wolf pack was willing to take them in and raise them as their own. For all Penelope knew, the Incorrigibles might not have survived without the care of those terrifying beasts.

Penelope’s rocking slowed, then stopped altogether. She thought of how nearsighted Lord Fredrick was, how prone to shoot first and figure out what sort of prey he had bagged later. “The most dangerous animal in the woods might well prove to be ‘Uncle Freddy,’” she thought with a shudder. “That settles it. If the admiral wants his ostrich back so badly, he is going to have to figure out how to catch it himself.”

AFTER THE CHILDREN WERE UP and dressed and fed a breakfast that was halfway to being lunch (for the boys had slept quite a bit later than usual), Penelope set them to work writing poems that had to a) be about some sort of bird, and b) use the same rhyme scheme as Mr. Poe’s “The Raven.” The children took up the assignment with gusto. Once their pencils were scribbling away, Penelope went off in search of the admiral.

He was behind the barn, just as the boys had said he would be, supervising the construction of a large, high-walled corral made of wooden posts and slats interwoven with lengths of twisted wire. Penelope had to dodge piles of lumber and burly workmen holding jagged-edged saws, but it did not slow her approach. She sported the set jaw and formidably upright posture that every Swanburne graduate learned in a required class called A Swanburne Girl Knows How to Make Her Point.

“Admiral Faucet, good day. I am sorry to disturb you, but there is an urgent matter that we must discuss.”

“Good day, governess.” He turned and bowed to her. “Those students of yours are extraordinary. Hats off on a job well done. How do you like my POE?” He gestured at the elaborate construction going on around them.

Penelope paused. She had planned to be stern and unyielding in her demands, but the admiral’s compliments caught her off guard, as did his reference to poetry. “Thank you, Admiral, that is kind of you to say. And I am a great admirer of Mr. Poe. The children are studying him right now, in fact. ‘Quoth the raven, nevermore.’ It has a jaunty sound to it, don’t you agree?”

“Not Poe. POE.” He waved a thick roll of blueprints around. “P. O. E. It stands for Permanent Ostrich Enclosure.”

Penelope gave him a puzzled look. “Why not just lock Bertha in the barn?”

“Governess, you may be a fine educator, but I can see you have no head for business.” The admiral twirled his cane, obviously in high spirits. “I plan to import the finest racing ostriches from Africa and sell them to the sorts of wealthy society people for whom racing Thoroughbred horses has become passé. Once they have an ostrich, they’ll need ostrich feed, and ostrich harnesses, ostrich trainers, and all the rest. Now, from whom are they going to buy all of that? Given that I will be the sole importer of ostrich equipment in Europe?”

“From you, I suppose.”

“Clever girl! I’ll be lucky to break even on the birds. The profit is in what comes after. Now, think, governess. The ostrich needs a place to live. If I say to my customers, ‘Just lock the bird in a barn,’ as you ignorantly suggest, where’s the profit in that? I can’t sell barns; England is full of barns! But I can sell a Permanent Ostrich Enclosure, manufactured on-site to these unique and patented specifications.” He smacked the blueprints against his leg with pride.

“Still, I am sure a barn would do in a pinch,” Penelope replied curtly. “Admiral, I must speak to you about the children.”

“Talented lads. Sorry Ashton and I kept them up so late. We were testing their tracking skills. Did you know those two boys can tell the difference between a badger print and a fox print at twenty paces? And they can do animal calls that sound just like the real thing.” He cupped his hands to his mouth and demonstrated. “Caw! Hoo! Ruff! The little one—Beowulf, is it?—sketched maps of the forest that showed nooks and crannies Ashton himself had never heard of. Strange fellow, that Ashton. An odd duck. But he’ll be my son-in-law if all goes well, so live and let live, I say.”

Penelope frowned. The first rule of making one’s point was “Stick to the subject at hand,” but the admiral was already off on a tangent and she would have to steer the conversation back to port, so to speak. “The children are quite talented, I agree. Unfortunately, your proposed expedition will interfere with their schoolwork. I regret that they will not be able to join you—”

“Nonsense, governess. They have to come. I need them.”

“Why?”

“To find Bertha, of course. Those lads can track, and they know the woods. And don’t tell me to use Ashton’s hunting dogs. I can’t. They’ll frighten Bertha into the hills and we’ll never see her again.” He leaned forward on his cane until his face was at the same level as Penelope’s. “Let me make something clear, Miss Lumley—that bird represents an enormous investment on my part, and I intend to get her back. These Incorrigible children of yours are remarkable! I’m tempted to take them on safari with me. They’re smarter than dogs, easy to train and transport. I need those boys to find my bird, and that’s all there is to it.”

“But Admiral—their lessons—”

He waved away her concerns. “Lessons, bah! Exploring is a highly educational business. Flora and fauna, latitude and longitude, points on the compass and all the rest. It builds character, too. Believe me, you don’t know what you’re made of until you’re alone in a canoe and drop your paddle in piranha-infested waters.” He made a fierce, rapid munching sound with his teeth that made Penelope shiver.

“No doubt it would be a grand adventure,” she interjected, for she had no wish to dream about flesh-eating piranhas that night; the murderous pheasants had been bad enough. “To be blunt, I am worried for the children’s safety. They told me Lord Ashton plans to bring his gun. As you may have noticed, his eyesight is less than keen.” Slyly she added, “He might pose a danger to Bertha as well.”

The admiral scowled. “At last you have made a valid point, governess. The boys are essential, but Ashton…Ashton is a problem. His mother is nearsighted, but the son is blind as a bat. He might very well shoot Bertha before we have a chance to catch her. Still, it’s his house, and his land, and I want him to think well of me so I can marry his charmingly wealthy mother, so I can’t just tell him to stay home, can I? Unless…” He pulled at his whiskers. “Is this full-moon business true? Does he actually turn loony once a month?”

“On occasion I have seen Lord Fredrick acting in a most peculiar way at the full moon,” she said warily. She did not fully trust the admiral, and so did not mention that Lord Fredrick’s most prized possession was an almanac with all the full-moon dates circled. Nor did she reveal that the master of Ashton Place had been known to disappear entirely on those nights, even if they coincided with important events, like a lavish holiday ball thrown by his wife, or the West End premiere of an eagerly anticipated new operetta about pirates. Nor did she say anything about the secret room in the attic of Ashton Place, from which a mysterious howling sound had, at least on one occasion, been heard, and that was during a full moon as well. But it did not matter, for the admiral had heard enough.

“That solves it, then. We’ll go when the moon is full. With any luck, Ashton will be too indisposed to come along. It’s a sneaky maneuver on my part, I know, but in the jungle, one must hunt or be hunted. You’d do well to remember that.” The admiral checked his pocket watch, as if this conversation had just run over its allotted time. “Don’t worry, governess. I’ll bring the lads home safe and sound. Now if you’ll excuse me, I need to inspect my POE.”

The admiral’s sense of adventure was as contagious as a bad pun, and Penelope was starting to feel the effects herself. And if Lord Fredrick stayed home, the danger of a wayward shot was all but eliminated…but this “hunt or be hunted” business made her deeply uneasy. She stepped in front of the admiral, blocking his way. “I must be clear, sir. Alexander and Beowulf are children, not hunting dogs. They cannot travel without an escort. If they are to accompany you into the woods, then I insist on going as well. And I shall have to bring Cassiopeia, as there would be no one to mind her in my absence.” This was not entirely true, of course, since in theory Penelope could have left Cassiopeia in the care of Margaret or one of the other housemaids. But Penelope knew Cassiopeia would never agree to stay behind when there was such a marvelous adventure to be had.

“Parts Unknown is no place for a young lady.” The admiral gave her an appraising squint. “Or a wee child. But you seem to have pluck, governess, and the girl is as fierce as a hyena, as I recall. Does she track prey as well as her brothers do?”

“I do not know,” Penelope confessed. “However, it is quite possible that she does.”

“The little growler might come in useful, then. All right. Join us if you must. But there will be no allowances made for teatime and nose powdering and all that rubbish. We will be ‘roughing it,’ as befits a band of brave explorers in the wilderness. Can you manage that?”

Penelope considered the offer. She was not in the habit of powdering, and she thought she could do without teatime so long as she had eaten a proper lunch. And just think of the fascinating letters she could send Simon, once their expedition was finished and Bertha was locked safely in her Permanent Ostrich Enclosure! He could not fail to be impressed.

“Very well. I accept your terms, Admiral.” She extended her hand to seal the bargain. The admiral shook it so vigorously it made her wince.

“Done!” he said. “We leave on the full moon. The hunt is on, governess. I hope neither of us comes to regret it.”