Judy conducting studio critique at Indiana University (IU), 1999

Judy conducting studio critique at Indiana University (IU), 1999

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, I was immersed in studio work and consequently unaware of the developments in academia as women’s studies programs took root in institutions around the country. In 1996 I collided rather dramatically with academic feminist theory when art historian Amelia Jones mounted an exhibition at the University of California–Los Angeles Armand Hammer Museum titled Sexual Politics: Judy Chicago’s Dinner Party in Feminist Art History, which was intended to contextualize The Dinner Party in twenty years of feminist theory and practice. It also included the work of fifty-five other feminist artists.

I can still remember my shock when members of the UCLA women’s studies department threatened to picket the exhibit because they felt that The Dinner Party degraded women through its supposedly “essentialist” imagery. At that time, I didn’t even know what essentialism was, though I quickly learned about it. In the early 1980s, some feminist art historians had begun to argue that The Dinner Party was, as Amelia explained in the exhibition catalog, “paradigmatic of a naive and putatively ‘essentialist’ arm of 1970s art.” She defined essentialism as “the unifying presentation of women’s experience as ‘essential’ or biologically determined.”20

Obviously, the relationship between nature and culture is complex and we are a long way from understanding exactly how biology and environment interact to produce human personality. At the same time, despite recent feminist theorists’ assertions that gender is a shifting construct and in contrast to the art world’s keen interest in gender-bending imagery, the truth is that for most women in the world, their biological sex shapes and constricts their lives. In fact, it was because the women represented at The Dinner Party table were female that they were unknown or under-recognized for their achievements. This was one of the points I was attempting to make through the imagery on the plates.

Moreover, I couldn’t understand how hundreds of thousands of viewers around the world had realized that the work was a celebration of women while others in the bastion of academia could come to such a wrongheaded conclusion. By the early 1990s—perhaps as a reflection of beliefs circulating in the larger culture—many studio art departments began promoting the idea that we now lived in a post-feminist world, one in which feminism and, consequently, feminist art were passé. However, what I was hearing from young women suggested that once they emerged from the cocoon of the university, they confronted a very different reality.

For instance, I vividly recall meeting one young curator who had mounted an exhibition at the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena that included my work among a preponderantly male roster of artists. She confided that in her previous job as assistant to a prominent male artist, he sexually harassed her. Additionally, many of the artists in the show had made unwanted sexual advances. She concluded her remarks by saying that nothing had really changed in the art world, a statement which suggested that the notion of a post-feminist world was a big lie, one that I will discuss later in this chapter.

My reentry into academia was initiated by Sergei Tschernisch, who was then the president of the Cornish College of the Arts in Seattle. In 1998, he invited me to present their annual commencement address, something that I’d never done before. The graduation was completely wild. The students were dressed in an array of costumes and each of the departments presented their teachers with gifts that were both funny and charming. All in all, it was a riotous event. In my remarks, I shared my experiences about the gap that I had encountered between art school and the art world, explaining how unprepared I was by my own university art education. I don’t really know how my talk was received, but I got the impression that the farthest thing from the graduates’ minds was what they would encounter on the other side of the diploma.

Some months later I was invited to present another commencement speech, at the Art Academy of Cincinnati. A few weeks prior to making the trip to Ohio, I had a phone conversation with a student at the school. As is my habit, I inquired about her experiences there. She told me about a life-changing class she had taken on women’s way of seeing. That’s the good news. The bad news was that the class was only offered once every three years and was in fact the only class that focused on women’s issues. It is distressing that, despite the fact that women make up the majority in most undergraduate art programs, a class about women was such an oddity—I mentioned this situation in my remarks.

Shortly before commencement, I met with some of the female faculty. They complained that there was an anti-female bias at the school. As if to demonstrate this condition, at the end of the graduation, there was an awards ceremony at which all the honors were given to male students. Sometime later, I received an extremely defensive letter from the school’s president touting the achievements of some of the earlier women artists who had studied there—as if that made any difference in terms of the current atmosphere.

That same year, Donald and I got a call from Peg Brand, a feminist philosopher who was teaching art and philosophy at Indiana University–Bloomington. She and her husband, the late Myles Brand, were coming to New Mexico and wanted to see us. Although we had never met them, I was familiar with Peg’s writing, which included some insightful comments about my work. I was eager to meet her and invited them to dinner.

When we moved into the Belen Hotel, Loretta Barrett, my literary agent at the time, had a leather-bound guest register made for us. When Myles signed the register, he listed his address as simply “Indiana University.” “Oh,” I said, “Do you teach there too?” “Not exactly,” he replied, “I’m the president.” What he didn’t mention was that he was the head of the whole eight-campus university system.

Despite my opening gaffe, we had a great evening. During dinner, I mentioned my interest in returning to teaching and some of my thoughts about studio art courses as they pertained to women. Peg was very receptive to my ideas. Unbeknownst to me, she had started out as a studio art major and had been driven out of her college art department by the sexist attitudes of her male professors. She took refuge in the philosophy department, which was more welcoming to her. Myles made a comment that night that stayed with me over the course of the ensuing years—he suggested that if I intended to start teaching again, I should make sure that I only took jobs at institutions of a certain level. Those words would subsequently come back to haunt me.

I soon received a formal offer to teach at IU–Bloomington during the Fall 1999 semester, which I eagerly accepted as the school was reputed to have a good studio art department. Over the subsequent months, Peg and I made plans for my residency. I was particularly interested in addressing the gap between art school and art practice, the subject to which I had alluded in my speech at Cornish. Many art students found this transition difficult, but it was especially challenging for women since many of them have little or no idea how to generate the money, space, or time necessary to set up a life as a professional artist.

Consequently, I proposed doing a project class that would allow students to experience the different stages of professional art practice—from identifying personal subject matter and formulating images to mounting an exhibition, which inevitably involves a myriad of challenges. My hope was that, by traversing the gamut of difficulties between creation and exhibition, the participants might become better prepared for the rigors of professional life.

Some months before the semester began I paid a visit to the Bloomington campus, where Peg held a gala dinner at the impressive university president’s house. It was my first exposure to the lifestyle of a university president and the demands it makes on a presidential spouse. Although Peg joked about it, calling herself the “first spouse” or “spouse girl,” I would come to understand how awkward a situation she was in due to the conflicting demands of her own career and Myles’s prominent position.

Nearly twenty women from a number of departments and campuses gathered to welcome me and to discuss how they could build programming around my residency. There were also representatives from various women’s studies departments who attested to the support that Peg had provided. Before her arrival, many of their departments were beleaguered; having a prominent feminist as the “first lady of IU” had been very beneficial to them.

As the evening unfolded, I could not help but notice the difference in faculty from when I was a student. Even though I didn’t believe that we had attained post-feminist nirvana, there did seem to be many more women in positions of power and influence. I thought maybe things had improved since the 1970s, when there were few women in high-level roles on campuses. But then several studio art professors mentioned that everything was not altogether rosy in their neck of the woods, especially not in the photography department. However, the atmosphere was buoyant and when the evening ended I felt quite encouraged.

Unfortunately my optimism was short-lived. The next morning Peg and I had a meeting with the chair of the art department, who happened to be a photographer. Almost as soon as we arrived, he started yelling at me. He insisted that there was gender equity at the school, which totally contradicted what I had heard the previous evening. His hostility was palpable and reminded me of what I’d encountered on occasion from male faculty during my visits at too many universities over the years. His behavior, like theirs, seemed to embody what was reported by Steven Henry Madoff: “Many schools are still struggling with artists who found their niche on their faculties…and then stopped growing—an unexpected perversion of tenure, which was meant to secure and promote radical thinking.…They perceive everything as a question of turf.”21 Obviously, I was encroaching on his.

I tried to tell the guy that nothing would make me happier than to discover that discrimination against women was a thing of the past—and not only at his university. However, it seemed that I could not dissuade him from his antagonistic stance. This was puzzling, because my salary was not coming out of department funds. Furthermore, Myles had decided to fast-track a space that would be used for the duration of my class and then be turned over to the art department. What really stunned me was that the fellow seemed to feel no compunction in expressing his animosity in front of the university president’s wife.

Sometime after this unfortunate exchange, I read an issue of Art Journal, a publication put out by the College Art Association (CAA), the major American art professionals’ organization. The subject was studio art education.22 Studying these articles, which were written by a range of studio art faculty and administrators, one would surmise that the chair of the Bloomington art department was right, that things had indeed changed. The publication led the reader to believe that both gender equity and diversity had been achieved in art departments around the country, or at least that serious efforts were well under way. As part of the application process for my IU class, however, students had been asked to write short statements about why they wanted to enroll, and the experiences they described suggested a less sanguine reality. Their accounts were characterized by a near-total disconnect between professors and some of their students:

“My experiences…have shown me that academics are more interested in developing the strictly technical aspects of their students’ work and they tend to shrink from any conversation having to do with artistic life.”

“I have noticed constant questioning by ‘educated’ male artists who did not take my medium seriously…(Also) the college does not offer classes that deal with feminism in art…(and I want to) learn from my history as a female artist.”

“I am a woman.…I want to produce feminist art and…express what it feels like living in this society as a female…and not be labeled a ‘Feminazi.’ ”

“It is time for me to learn the history of artists who were women. I need to know what it means to do work that reflects who I am. . . (as it) becomes more apparent that the experiences…in my work are those of a woman, I have encountered an unexpected sort of energy from men. Suddenly my work is labeled as ‘feminist,’ as if that were something negative.”

“Upon doing a paper addressing the position of women in the arts…including a discussion of the Feminist Art Program, I was told by my instructor that the feminist art movement had ‘phased out long ago’ and my interests in it were ‘passé.’ Nonetheless, I intend to study and write about women artists and feminist art issues even though it makes me feel alienated and unguided in graduate school.”

These conflicting testimonies indicate that, for many female students, conditions were far from ideal.

In late August 1999, Donald and I set out for Bloomington, hauling a trailer full of clothes, art supplies, and portable studio equipment so that I could set up a temporary work space. We also packed up our six slightly sedated cats, who were going to spend the semester with me because I had decided to do a series of watercolors about life with our feline family and wanted the kitties around so that I could closely observe their habits. Peg had arranged for me to rent a spacious, light-filled, university-owned house on the edge of campus for an extremely modest cost. Its only drawback was its proximity to the football stadium—whenever there were games, I became a virtual prisoner in the house because cars were parked everywhere, even blocking my access to the street.

Other than that, the house was great and on a big lot set back from the street. Peg and some of the president’s staff were there to greet us when we arrived. They helped unload the truck, then stayed to assist with the unpacking. Donald set up my studio in the basement, which a former tenant had converted into a cavernous, den-like space with knotty pine walls. He stayed for a few days then flew back to New Mexico. This left me with plenty of time to work in the studio—my only interruptions were teaching and near-weekly dinners with Peg and Myles.

Despite the fact that Peg had played a pivotal role in bringing me to campus, she was hesitant to take the class. I didn’t even know she was interested until the semester began. She kept attending the sessions, at first under the pretext that she was making sure everything was going well. Once it became clear that she wanted to participate, both the students and I urged her to do so. Even though she had presumably stopped making art many years before, she continued to feel a longing to paint, which is why she ended up joining the project shortly after it began.

Although the class was open to both sexes, only women applied. This disappointed me, as I had hoped to see if my pedagogical methods could be useful to men. As it turned out, they wouldn’t be tested in that way until the following year. However, students from all eight campuses did enroll; they ranged in age from women in their early twenties to sixty-year-old returning students who had already entered into professional practice.

Unfortunately, once on their own, some of the more established artists had discovered that they were unable to work—at least not in any regular way. A number of them felt stranded without the support of professors and peers; others felt overwhelmed by the problem of earning enough money to support themselves while finding enough time for their work; some were unable to figure out how to finance and set up their own studios and buy materials. Their dilemmas exemplify my earlier point about the gap between art school and art practice, especially for women. Instead of resolving these challenges, they reenrolled at the university, which just postponed the problem.

The IU project class began as all my courses do, with introductions followed by self-presentations, during which each student shows her work and talks about herself and her artistic goals. Through this process, people identify their interests and concerns, which helps them to locate subject matter they wish to explore. Actually, I believe that many artists work with personal content but it often goes unrecognized because of the nature of contemporary art language.

From my own university studio art education, I learned to “talk in tongues,” that is, to make art that was virtually unintelligible to viewers because the form disguised—rather than revealed—the actual subject matter. Increasingly, understandable content in art has come to be seen almost like an infectious disease, something to be avoided. To whit, in an extremely influential essay, “Against Interpretation,” Susan Sontag argued that, “Whatever it may have been in the past, the idea of content is today mainly a hindrance, a nuisance, a subtle or not so subtle philistinism.”23

In the Introduction to Art School, Steven Henry Madoff commented that the contemporary “art-for-art’s sake stance…has generated a fear of narrative content…that is not serving us well in the twenty-first century. Modernism defined universalism partly through form, devoid of social content, but this has become a repetitive formula, an armor without a body, ultimately decorative.”24 In fact, in my opinion not only is content important, it should be expressed clearly so that it can be understood by viewers.

The first step toward achieving this in my classes is taken with the self-presentations, which are often very honest and open. In addition to initiating a process of sharing, they help to create a sense of connection between group members. Once artmaking begins, the group provides encouragement as the students move beyond their perceived limitations. This experience of group support promoting individual achievement is one that few women have—unless they participate in sports. Of course, this support is exactly what the 1970s consciousness-raising groups provided their members, though artmaking was not their goal.

During this phase of the IU project class one student, Yara Clüver, showed a series of landscape photos, saying that she intended to continue with them, but it soon became obvious that she was preoccupied with family problems. I suggested that she focus on those as the subject matter of her art. Her husband had developed Crohn’s Disease, an autoimmune, inflammatory disease of the gastrointestinal tract. Their daughter also suffered from digestive problems that were preventing her from nursing. A feeding tube had to be inserted into the child’s body so that she could get nourishment.

Once freed to address the issues with which she was actually concerned, Yara was able to utilize her considerable skills as a photographer to transform her life challenges into powerful images. Her photos presented her family’s naked bodies—the birth-induced stretch marks on Yara’s torso, the ravages her husband’s bouts with Crohn’s disease had wrought on his frame, and the baby taking in her mother’s previously pumped breast milk through a feeding tube.

However, in order to produce this moving work, Yara had to struggle with her own resistance to letting others know about her life; like many people, she viewed it as a private matter. And it might have been. But what was going on at home was making all else pale in comparison. Consequently, her landscape photos were lacking in effect. They didn’t reflect her real concerns.

Even though working with personal subject matter may be therapeutic, the process of making art is quite different from therapy. Healing is not the goal, though it can be an outcome. The purpose of mining one’s experiences in an art class or studio is to find meaningful subject matter that has the potential to be transformed into expressive visual images. Unfortunately, in the present system of university studio art education, students are often dissuaded from seeing art as a form of communication, which is what I believe it to be. Hence my emphasis on comprehensible imagery.

Yara Clüver, Built to Suck, 1999. Photographic triptych

After the IU self-presentations, I worked individually with the students. Some of them found their subject matter early on or came to the class already knowing what they wanted to explore. Others were slower to find their content, so I would help them think about their interests until they identified the subject matter that inspired them. Then I would assist them in formulating a project that drew upon their particular skills. Because they were moving from content to form, they could employ whatever technique or combination of techniques seemed most appropriate.

Almost all of the students—including the older women—displayed a lack of confidence. Perhaps the authors of Still Failing at Fairness provide an explanation for this situation: “Sitting in the same classroom, reading the same textbook, listening to the same teacher, boys and girls receive very different educations. From grade school through graduate school, female students are more likely to be invisible members of classrooms. Teachers interact with males more frequently, ask them better questions, give them more precise and helpful feedback.…Girls learn to wait patiently, to accept that they are behind boys on the line for teacher attention. Boys learn that they are the prime actors shaping…life.”25

One advantage of an all-female class is that there are no male students to grab the limelight—the women get all the attention, which can boost their confidence if the teacher is supportive. Moreover, according to the same book, “In the typical college classroom, 45 percent of students do not speak; the majority of these voiceless students are women.”26 This dismal fact helps to explain the need for a pedagogy that includes everyone and employs the strategic use of silence to make sure that all the students find the courage to speak.

Judy Chicago with IU Bloomington students, 1999.

In addition to a lack of confidence, most of the IU students suffered from an inability to formulate realistic ideas. Their conceptions tended to be either overly grandiose and hence beyond their reach technically or financially or too vague to be achievable. We discussed all these problems with an eye on overcoming them. Before long, everyone was focused on their respective projects—although we explored the possibility, there seemed to be no interest in doing collaborative work. I met with the class each afternoon to discuss their progress and to help with any difficulties.

At one point a few of the students began to struggle with me, probably because I was pushing them to think through their ideas more thoroughly and communicate them clearly (i.e. not to ‘speak in tongues’). In response, they either became angry or changed their plan, insisting that I tell them whether their new concept was valid. I tried to point out that an idea is just the beginning, that most are only as good as the investment you are prepared to make in them. You can begin with almost any intention. One of my favorite stories about Josef Albers proves my point. When he was asked why he had chosen a square as the primary format for his paintings, he responded, “One had to put color on something.”

It was precisely when the students had to begin investing weeks of work in their projects that they began to falter, a rather common occurrence among women, who, as I’ve suggested, often lack confidence in themselves and their ideas. In one instance, I literally stood behind a young painter and urged her to walk straight ahead, all the while insisting that she not veer to the left or the right but just keep moving forward. My intention was to demonstrate physically that you had to make a commitment to an idea, then keep working until it was realized. Only then could its value be ascertained.

Once the students were over that obstacle, they were on their way. Not that there weren’t bumps along the road and tears, which seem to accompany whatever women do, at least in my experience. I tried to urge them on whenever they became uncertain and to keep them on course whenever the going got tough as it inevitably does in the creative process. An idea can seem so great when it’s in your mind but as it takes physical form a yawning gulf often opens up between conception and creation.

This is where a facilitator-type teacher can be especially crucial in helping students accept that their perception of their ability may be at odds with their capacity (in terms of talent, time, or money) to visually express their ideas. All budding artists must go through this experience as they build proficiency. Instead of giving up, students need to be encouraged to conceptualize a project that they can handle, to work harder, and to keep trying—over and over again if necessary.

Early in the semester at Bloomington, the class paid a visit to the I. M. Pei–designed university art museum, which was where the students would be exhibiting their finished creations. Particularly for the younger women, conceptualizing their work in terms of how it would look in a public space was a new experience. Kathy Foster, the curator at that time, helped the students to think about what it meant to do a museum show. She also proved to be invaluable when it came time to set up the exhibit. In addition to discussing installation issues, we talked about signage, announcements, and publicity—all important aspects of planning a show.

Because a number of the students had never been in an exhibition, I wanted to prepare them for the possibility that they might encounter the type of criticism, rejection, and/or indifference that sometimes greets contemporary art, especially if it is content laden. Although it is difficult for any artist to deal with a myriad of reactions to his or her art, it is my experience that this is particularly true for women, who often find it difficult to handle criticism and tend to take it personally.

Another challenge for most of the participants was the amount of time required to complete their projects, especially as the opening drew near. Allocating time for work—a basic concept of professional practice—is always difficult for women. who often have to balance multiple demands. But learning what it means to work at a professional level is essential for anyone who hopes to make a go of it as an artist.

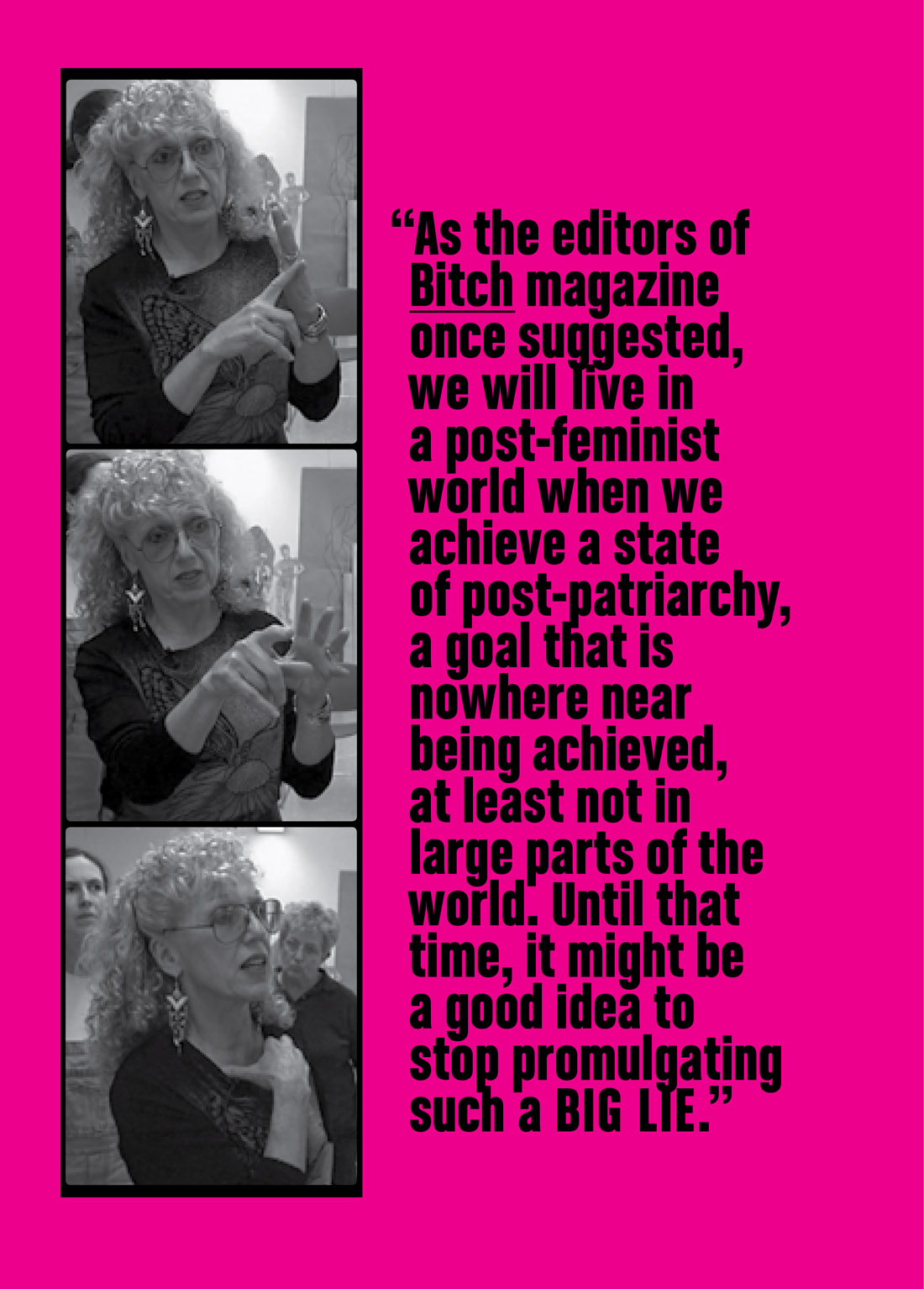

SINsation Postcard Announcement. IU Bloomington, 1999

Not everyone succeeded in their artistic goals. One of the older women wanted to deal with some persistent and troubling body issues. She had cast her body in plaster, but she kept covering up the form with cloth, probably because she felt ashamed of how she looked, as many women do. She and I argued about it. Finally I threw up my hands, feeling that she had a right to determine the level of self-exposure with which she felt comfortable. In other cases, students outdid themselves, creating images that were far beyond anything their earlier work had suggested was possible.

Peg had arranged for a film, No Compromise, to be made about the class by Susanne Schwibs, who works in IU’s Department of Communication and Culture. Filming started early, when the students first gathered in the large empty space that would slowly be transformed into a bustling studio. The documentary provides considerable insight into my teaching methodology which, as the title suggests, could also be called “tough love”—a combination of high expectations along with generous support and guidance. The film also documents the class’s exhibition, which was titled SINsation, a takeoff on the controversial 1999 Sensation show of young British artists from the Saatchi Collection at the Brooklyn Museum.

Installation view, SINsation. IU Bloomington, 1999

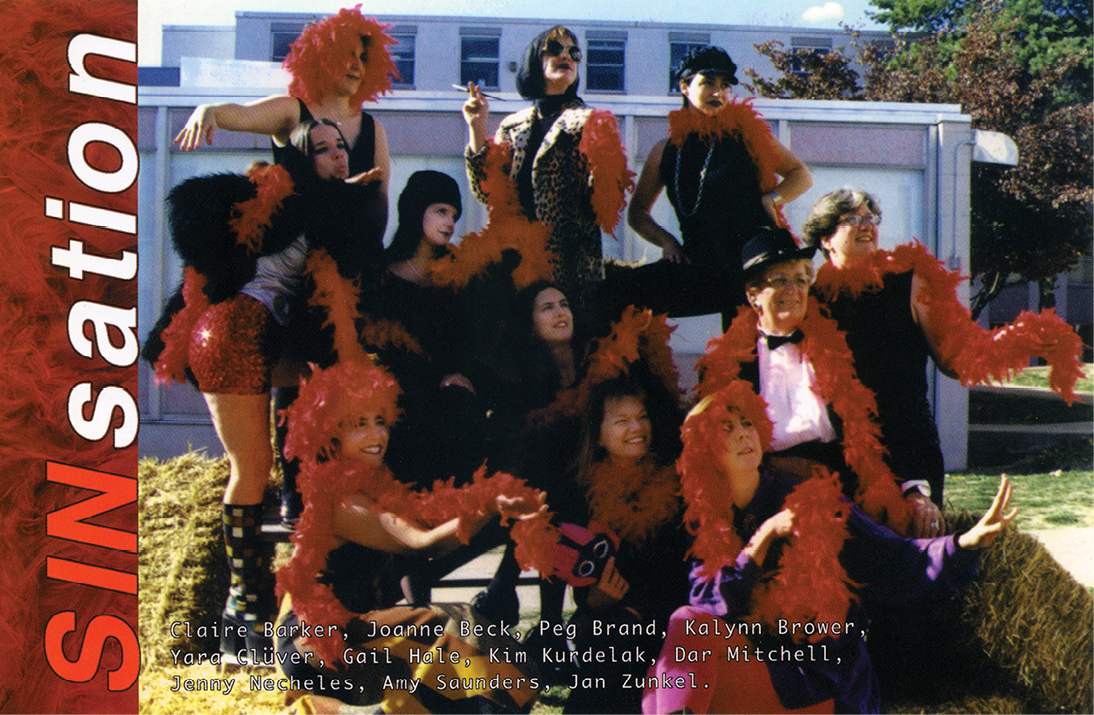

Some of the works in our show were pretty controversial themselves. For instance, one charming young woman, Amy Saunders, created a life-size, plaster sculpture of a male figure—complete with erection, upon which she hung a towel. The witty title was Towel Rack, though I am not sure that everyone enjoyed the pun. She also created an installation consisting of a series of bold, red digital prints that incorporated a photo of her vagina. Over these, she painted simple images based upon various degrading slang expressions like “pussy,” “muff,” and “beaver.” Exhibited nearby was her journal, which chronicled both her painful childhood and her positive experiences in my class.

There were several other sculptures. One was a full-size image of a woman ripping open her body to expose bruised innards, symbolizing the years of abuse that the artist, Dar Mitchell, had endured. Another involved a giant hoop skirt suspended from the ceiling, from the center of which descended a uterine form composed of immobilized roses. There was also the aforementioned plaster body cast by the woman who had insisted upon obscuring the form with layers of cloth. As a result, it looked like an ossified mummy, though the artist had added another figure ascending from it, as if in flight.

Amy Saunders, Dealing with Ongoing Sexist Attitudes, 1999.

Dar Mitchell, Untitled, 1999.

Three large relief images of women—two in textiles, the other in sheet metal—graced one long wall. Paintings depicting Jan Zunkel’s maternal heritage (with its constricting gender expectations) was juxtaposed with an antique armoire that seemed to overflow with a cascade of shoes. There were some striking images painted in oil on surfaces made of collaged paper and matte medium and a touching though somewhat naive series of watercolors depicting one student’s Jewish wedding. Peg’s contribution was an amusing parody of one of Willem de Kooning’s Woman paintings, reconfigured so that viewers could have a photo taken with their own faces substituted for the original head, which had been carefully cut away.

Jan Zunkel, Untitled, 1999. Mixed media installation

The opening of SINsation was a huge success; many hundreds of people attended. Most viewers seemed bedazzled by both the range of work and its excellence. I walked around the show with Myles, who later wrote to say that he “was overwhelmed by what I was able to accomplish with these students in a short period of time.” Subsequent teaching projects would also result in successful exhibitions, which I will describe later in order to demonstrate what my content-based pedagogy has produced. As they say, the proof is in the pudding.

As part of my IU residency, I team-taught a graduate seminar with Peg. Early on, we decided it was important to include an art historian in the course, which was titled “Feminist Art: History, Philosophy, and Context.” But locating a collaborator proved to be difficult. At that time, the head of the art history department on the Bloomington campus was reputedly right of Attila the Hun. Given his political leanings, it came as no surprise that the guy was hostile to feminist ideas or that no one from his faculty would work with us—to do so would have amounted to professional suicide. We finally found Jean Robertson, who taught at the Herron School of Art and Design in Indianapolis, a member of the IU system.

Peg Brand with her parody of a Willem de Kooning “Woman” painting, 1999.

Although a listed prerequisite for the class was a knowledge of feminist theory, I was frustrated to discover that we would have to give the students more basic grounding in feminism (which Peg graciously provided) before we could begin to consider the task of defining feminist art, which was the purpose of the seminar. To this day, there is little consensus among artists, writers, critics, and historians as to what exactly constitutes a feminist art practice. I believe that one difficulty lies in the fact that feminist art is content based; most previous art movements are defined by a singular style. Whatever the hurdles, they are complicated by the fact that some artists who are ardent feminists insist that their work—though abstract—should be included in this definition, even though few viewers would be able to discern any feminist content.

Other artists, such as Tracey Emin, whose work is openly concerned with gender issues refuse to call themselves feminist artists, perhaps because the term has developed such negative connotations in the art world—as has the term feminism in general. To further complicate matters, one prominent New York critic, while acknowledging that feminism has had a profound effect on contemporary art, has argued that there is no such thing as feminist art. Nevertheless, the term has entered the art-world lexicon and we thought it would be interesting to engage the seminar students in a dialogue that might lead to greater clarity about its definition.

Perhaps our expectations were unrealistic given that the art history graduate students had barely even been allowed to do research on women artists, much less venture into the new intellectual territory that had opened up since the advent of feminist theory. For instance, the distinguished artist and critic Mira Schor (a former student of the CalArts Feminist Art Program) wrote a groundbreaking article, “Patrilineage,”27 that critiqued the continued practice of referring to a patrilineal rather than a matrilineal tradition in relation to women’s art. By way of example, consider an article in a prominent art magazine about Elaine Reichek, whose work draws on the tradition of embroidered samplers. There are many precedents for Reichek’s art in both conventional embroidery and the work of feminist artists including Miriam Schapiro’s “Femmages,” which often incorporate fabric, not to mention my own extensive use of needlework in a number of projects.

Yet, instead of considering Reichek’s stitched images in relation to the history of feminist art, her work was placed in a male context that includes artists like Andy Warhol. This makes absolutely no sense in terms of the imagery or the technique. And it’s a perfect illustration of Schor’s point. Perhaps critics think that the best way to give credence to a woman’s work is to compare it to a man’s. But this is the wrong approach. Rather, women’s history, feminism, and feminist theory must be integrated into mainstream curricula. Only then will there be a more appropriate historic context in which to evaluate what women do.

Another reason for my dissatisfaction with the graduate seminar was that most of the students seemed reluctant to put forth any new theories in their writing. The first-draft abstracts for the final papers were, to my mind, pretty dull. Perhaps I was anticipating a level of risk-taking that is more common among artists than academics. After all, in order to create, an artist must take chances; one faces a blank canvas or an unformed lump of clay and is forced to make decision after decision based only on one’s intuition. Perhaps it is different for academics in the sense that they are trained to “prove” every point by citing previous research. In one session I blurted out that I was not satisfied with the abstracts because they rehashed old ideas. In response, one student said that “going out on a limb intellectually is not how one obtains tenure.”

One conclusion that might be drawn from this experience is that I am better suited to studio teaching than to that type of class, which might be true. However, some time later Peg told me that she and Jean were team-teaching the feminist art seminar again, which pleased me. Perhaps the repetition and development of this class will eventually encourage some students to become less timorous.

There was one unexpected and positive outcome from the IU seminar class, though. At some point in the semester, Terry,28 a theater major, proposed organizing a group of theater students to restage both the Cock and Cunt play and Faith Wilding’s “Waiting” as part of the class exhibition. He also wanted to work with what turned out to be an all-female group to create some new performance pieces—again, no men signed up when the call for participants was circulated. For some unknown reason I just assumed that Terry would be able to use my methodology without any training, which turned out not to be true, at least not in terms of the original performance pieces. I didn’t think that anything fresh was brought to the new staging of either the Cock and Cunt play or “Waiting”—perhaps the politics of housework and female passivity were not as relevant to a younger generation—but several of the newly created pieces were quite potent and informative about the difficulties young women were facing.

As mentioned, by the time I arrived at IU, post-feminism was all the rage, particularly in academia. As Andi Zeisler and Lisa Jervis put it in the introduction to Bitchfest, “all of a sudden, there were books about postfeminism, references to it in film and literary criticism, even an entire website called the Postfeminist Playground where a group of women wrote about sex, culture, and relationships from a standpoint that assumed a world where the gains of feminism were unequivocal and its goals roundly met.”29

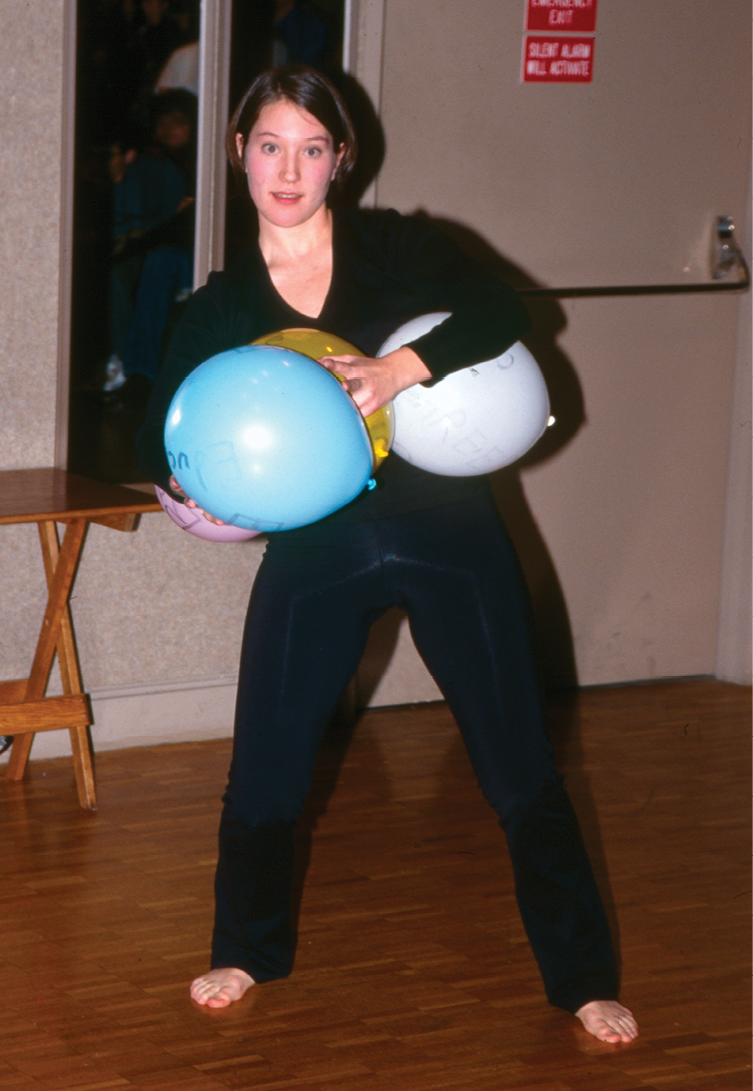

Balloons performance, 1999. SINsation. IU Bloomington, 1999

But the IU students’ performances conveyed a different story. The most telling piece involved two women dressed in black leotards, one sitting on the stage, the other entering and exiting wearing a clown wig. While circus music played in the background, the clown character kept reappearing and dropping balloons in the lap of the seated performer, who blew them up. Each of the balloons was labeled with a word that evoked a source of pressure: parents, education, friends, career, relationship, and finally, baby.

Once that last balloon was dropped in her lap, the seated performer made it clear that it was impossible to balance them all—a seemingly perfect metaphor for the predicament these young women were facing. Apparently, they were being encouraged to believe that equality had been achieved, that they could do and be what they wished. But their life experiences were contradicting this rosy view. Soon thereafter, I tried to share what I’d learned from the students’ performances, but with an unfortunate result.

In the spring of 2000, I visited Smith College to receive an honorary doctorate and present the commencement address. I was struck by the beauty of the setting, which was verdant and pastoral. Donald and I strolled down Paradise Road and past Paradise Pond, slowly taking in the atmosphere of a university that offered its all-female student body four years in what seemed like heaven to me—a school that made women the focus in an absolutely gorgeous environment.

Graduation day brought warm, beautiful, sunny weather and the ceremony was nice as such festivities go. Prior to our trip, I had had a phone conversation with Smith’s president at the time, Ruth Simmons, the first African-American woman to lead an Ivy League college. I wanted some guidance from her about my commencement address. She advised me to speak honestly about some of the lessons I’d learned during my life. For that reason, I decided to talk about the IU performance piece and what it had taught me about the problems young women were having balancing the conflicting demands in their lives. At one point I said that even though it was not fair, women still could not “have it all,” that they had to make hard choices if they really wanted successful careers.

A few days after the Smith commencement ceremonies, I received an e-mail from Peg Brand saying that she had heard a show on National Public Radio about commencement speeches and that my talk was mentioned quite favorably by the interviewee, a man who had written a book about the best graduation speeches of the last twenty-five years. My pleasure at his response lasted about an hour, until Donald received a teary phone call from his mother, who lived outside Boston. The Boston Globe columnist Eileen McNamara had viciously attacked my remarks. As soon as I read her commentary, I e-mailed Smith’s provost; I knew Boston was too close to the college for the piece to have gone unnoticed. I asked if the administration was upset by the article, but he reassured me that they had invited me to speak my mind and that is what I had done.

However, as has often been my experience, negative press sometimes brings unexpected consequences. For example, there can be an unacknowledged reluctance to maintain contact with the person who had (intentionally or not) generated the reaction. On a more positive note, there was a full page in the New York Times (May 30, 2000) devoted to quotes from various commencement addresses, including mine. I was right up there with people like (then) Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, which made me feel a lot better—for a little while. Soon afterward, at an opening of one of my exhibitions, we ran into some old friends who informed me that several Smith alumnae had told them that my speech was quite contentious, and had added that I had supposedly advised the students that they had best stay at home. To our friends’ credit, upon hearing this, they responded, “I don’t think so,” rightly assuming that this would not be advice that I would proffer.

This brouhaha raged on for months. At one point, Ruth Simmons sent me a copy of the Smith College magazine. It contained a number of letters to the editor from mothers who expressed outrage about my daring to suggest that conditions for their daughters might not be as favorable as they had been encouraged to expect. Ironically, in that very same issue, there was an essay about female lawyers and the conflicts that they developed in their efforts to balance work and family life—this must have gone unread by the outraged parents of the graduates.

Apparently, like many people, they held what the Newsweek columnist Anna Quindlen described as “a charmingly naive belief”30 that women have achieved equality. This conviction is also undermined by the facts cited in a much-referenced article by Anne-Marie Slaughter, “Why Women Still Can’t Have it All.” She reports that out of “a hundred and ninety heads of state; nine are women. Of all the people in parliament in the world, 13 percent are women.”31 Her main thesis is that an absence of family leave policies forces women like her—the first female director of policy planning at the State Department—out of demanding careers. She says, “I could not stop thinking about my 14-year-old son, who had started eighth grade three weeks earlier and was already resuming what had become his pattern of skipping homework, disrupting classes, failing math, and tuning out any adult who tried to reach him.”

My reaction to the piece was, “What did she expect? If a person wants to be part of the public conversation and influence policy, maybe it’s better not to have children. And if you really want a family, then that should be your priority, because children’s needs cannot be made to accommodate the demands of a high-profile job.” Like Slaughter, I lament the fact that so many highly trained and competent women leave the public arena because—as her statistics prove—there are not enough women shaping the world’s policies. But the situation will not change until women recognize that it is not yet possible to “have it all.” Everyone has a limited amount of energy.

Many years ago I spoke at a private girl’s high school in Connecticut. After my talk, one of the students asked me if had children. When I said no, she asked why. “Because I didn’t want them,” I answered, which left her flabbergasted. She had never heard a woman say such a thing. I am not arguing that people shouldn’t have children if that is what they want. Nor am I suggesting that only women be responsible for child-rearing. But it seems to me that life is about making choices. Not having children must become an acceptable choice if women are going to enter the public sphere in enough numbers to begin to change it, which is what Slaughter is arguing (and I certainly support).

I must admit that the controversy surrounding my Smith commencement speech was confounding. Why were people so upset with me? I had simply reported on what I’d observed—that young women were being offered a view of life that would prove untrue once they left the comforting embraces of family and school. Why are so many people intent on believing and promoting a false picture of reality? It certainly doesn’t help their daughters. The young women end up confused or, worse, trapped in the consequences of choices based upon the false premise of a post-feminist world.

As the editors of Bitch magazine once suggested, we will live in a post-feminist world when we achieve a state of post-patriarchy, a goal that is nowhere near being achieved, at least not in large parts of the world. Until that time, it might be a good idea to stop promulgating such a BIG LIE.