A Brief Review of Personality Since McDougall

The Need for a Bottom-Up Model of Personality

“Dynamic” has come to be used in a special sense: to designate a psychology which accepts as prevailingly fundamental the goal-directed (adaptive) character of behavior and attempts to discover and formulate the internal as well as the external factors which determine it. In so far as this psychology emphasized facts which for a long time have been and still are generally overlooked by academic investigators, it represents a protest against current scientific preoccupations. And since the occurrences which the specialized professor has omitted in his scheme of things are the very ones which the laity believe to be “most truly psychological,” the dynamicist must first perform the tedious and uninviting task of reiterating common sense.

—Henry A. Murray, Explorations

WHILE WILLIAM MCDOUGALL was one of the first to write a book about personality, many others followed that offered comprehensive models attempting to explain how humans develop their consistent patterns of behavior. In this chapter, we briefly review a representative selection of personality models after McDougall and argue that personality theorists increasingly departed from the primary instincts and emotions that Darwin wrote about and that provided McDougall with his starting point.

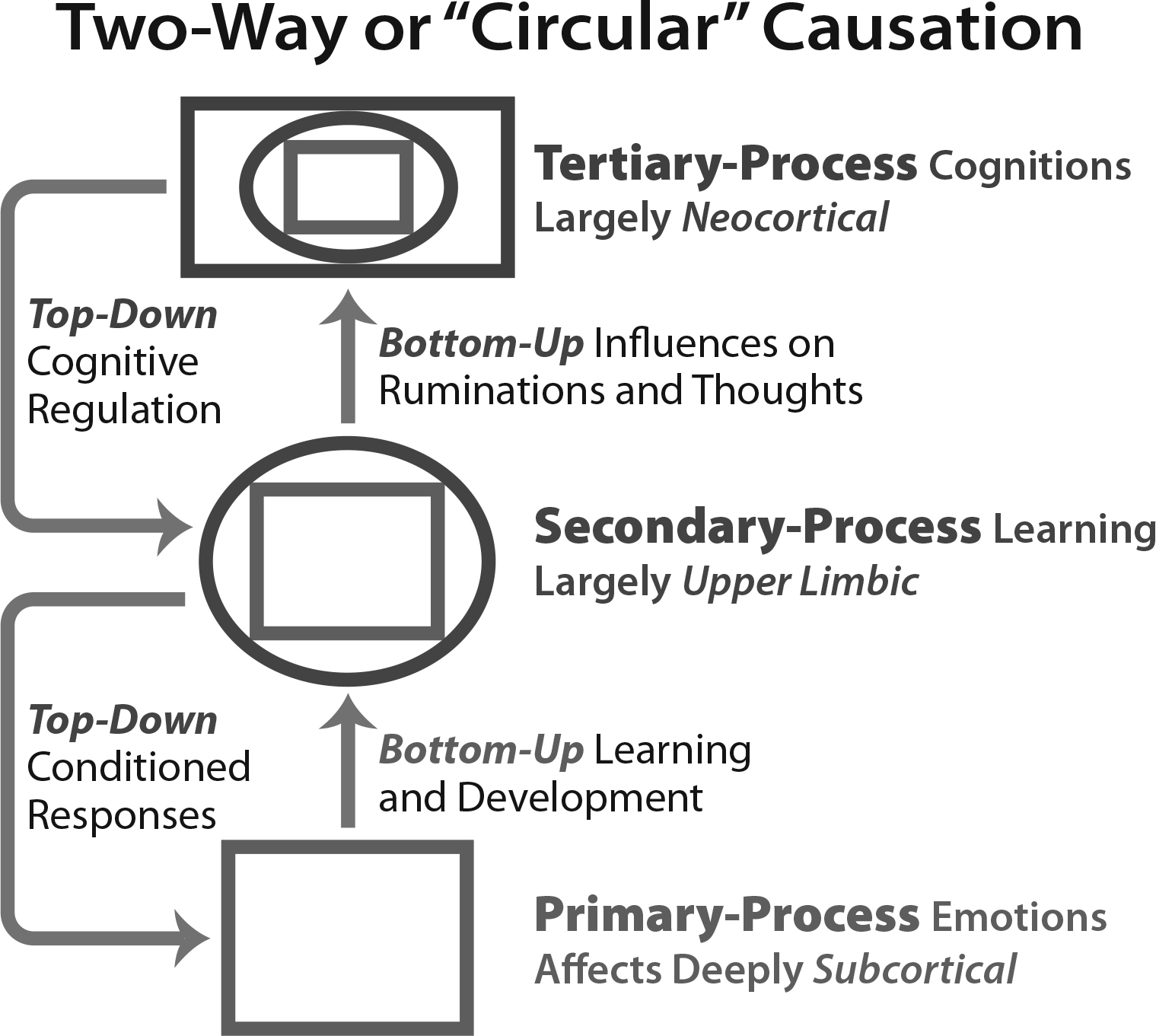

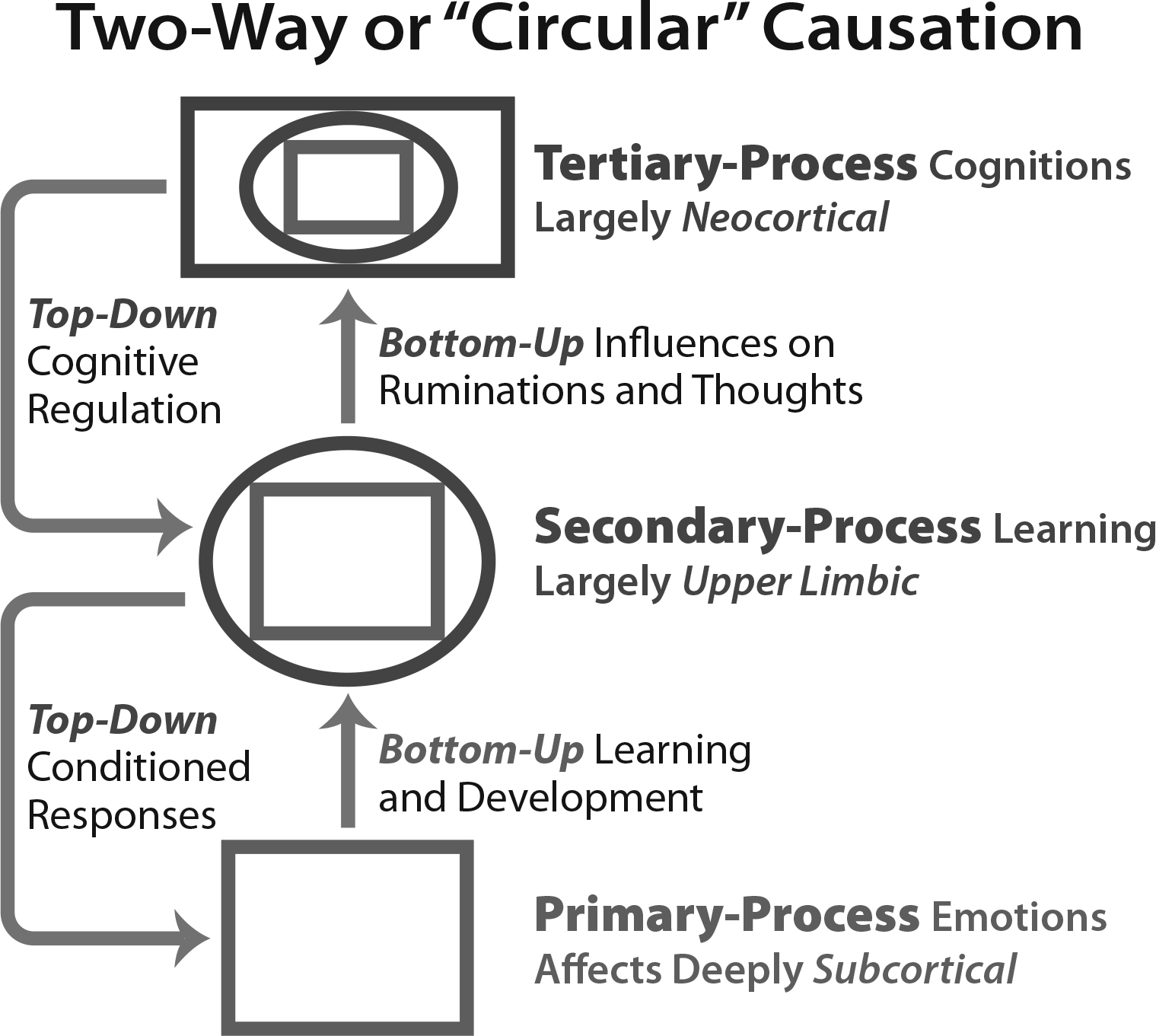

At the end of this chapter, we will reinforce our view that to fully understand human personality we need first to understand how feelings arise from our subcortical brains (feelings that, in general principles of operation, are shared homologously across mammalian brains) and how those primary emotional feelings are elaborated and complexified throughout our lives. Because affective feelings are survival indicators—with all positive/good feelings signaling potential thriving and all negative/bad feelings automatically projecting potential destruction—it seems likely that these brain circuits are major controllers of what we learn about the world. We will present a three-level, Nested BrainMind Hierarchy (NBH) model that may facilitate discussions about the fundamental sources of personality by clarifying the level at which the various discussions and disputes are taking place along a continuum: from the emergence and expression of primary emotions, to secondary learning and memory mechanisms that help us adapt to our specific environments, and to tertiary-level cerebral capacities that offer us abundant neurocomputational space to advance thinking, especially through the development and use of language (and ultimately mathematics). But first, we start with a short discussion about another early personality theorist who started with a fundamental base of primary emotions.

FREUD AND PSYCHOANALYTIC THEORIES OF PERSONALITY

Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) was a contemporary of William McDougall (1871–1938). Fifteen years older than McDougall, Freud completed his first book, The Interpretation of Dreams, in 1900, just eight years before McDougall’s Introduction to Social Psychology (1908). Like McDougall, Freud based his theory on biological drives or instincts. Freud’s id was the reservoir of the life and death instincts. With some literary liberty, we would translate life as good feelings (i.e., affects that intrinsically predict survival), and death as bad feelings (feelings that predict potential destruction). In his early psychoanalytic writings, Freud focused on the sex instincts, or what we would call LUST. After World War I, Freud concluded that aggression—what we would include in the RAGE/Anger system—could be as potent a motive as sex.

In his early years, before the development of psychoanalysis, Freud aspired to explain clinical disorders using cerebral anatomy (see Mark Solms’s forthcoming translation of Freud’s early neuroscientific investigations). However, Freud soon came to accept that the available neuroscience research tools would not provide him the answers he sought. It should be noted that the International Neuropsychoanalysis Society (founded in 2000 by Mark Solms) is dedicated to linking brain neuroscience with psychoanalysis, which is something that Freud openly dreamed about.

So for the remainder of his clinical career, Freud pursued psychological-developmental theory and the treatment of psychopathology with psychoanalysis, which was his variation of a new method of therapy he had learned from a fellow Viennese physician Joseph Breuer, in which patients were cured by talking with their physician about their symptoms—their hopes and their worries. It is now generally recognized in psychiatry that frank discussions, with a receptively intelligent other, of where patients are in their affective life is solid path toward self-understanding, acceptance of life’s vicissitudes, and finding paths to well-being.

We will not delve into the details of Freud’s theories—we assume the typical reader is already reasonably familiar with Freud’s work. However, we feel that Freud’s thinking was close to affective neuroscience in spirit, especially because he based his theory on inherited instincts that were ancestral “gifts,” many present at birth, which from Freud’s perspective over one hundred years ago were divided into unconscious libidinal and destructive drives. He was using unconscious in the typical way: not on the basis of understanding qualia (namely raw experience itself, on which affective neuroscience has focused) but, rather, on whether we are aware (ideally with some understanding) of these primal sources of mind.

Retrospectively, we might suggest that the Victorian period in which he lived misled Freud to include infant nursing in what we would label the LUST system. In affective neuroscience terms, infant feeding would more likely belong in the homeostatic HUNGER system, which we would not include as a primary influence on personality. By contrast, emotional affection and bonding emerge from maternal CARE efforts and experiences. Although there is surely a substantial role for maternal nursing dynamics in infant social bonding, Harry Harlow’s experiments with surrogate artificial mothers suggested that the simple act of an inanimate “mother” feeding a baby was less relevant for socially bonding than the experience of maternal warmth and physical contact. We might also argue that maternal nursing would more likely involve maternal bonding to the infant via the mother’s intrinsic CARE system. Thus, out of lack of detailed knowledge of subcortical emotional systems, perhaps Freud overemphasized concepts like the “oral period” and “infant sexuality.” We simply do not yet have sufficient evidence on that point. Still, Freud’s thinking remained anchored in instinctual systems even as his theorizing became increasingly linked to his clinical practice and the specific life problems of clients.

Along these lines, Freud popularized the idea of the unconscious, which he felt accounted for the phenomenon of psychological repression, the symbolic content in dreams, and “slips of the tongue.” He is also credited with introducing transference, a concept that is highly developed in psychoanalysis but that for personality purposes can be thought of as how earlier significant relationships influence our subsequent relationships. Thus, Freud’s theorizing became increasingly conceptual and difficult to verify or even link to primary emotions. In the section that follows we continue this theme, showing how clinically based theories after Freud lost clear linkages to the primary emotional systems and came to represent ever more conceptual psychological approaches to pathology and personality.

With the psychopharmacology revolution, Freud’s theories and psychoanalytic approaches lost influence in the academy. However, this is changing with the modern neuropsychoanalytic movement (see Panksepp & Solms, 2012), where interest in the neural nature of affect is intense (see Fotopoulou, 2010).

JUNG’S ANALYTICAL PSYCHOLOGY

The young Carl Jung became Freud’s closest follower, to the point that Freud, two decades older, decided Jung would be his successor. However, Jung eventually seceded from Freud’s inner circle, apparently because in his own psychoanalytic theory Jung came to reject Freud’s strong emphasis on sex. By 1914 Jung (1875–1961) had completely struck out on his own path.

Jung’s analytical psychology did not include an id, which in many ways was replaced by his “collective unconscious.” For Jung the collective unconscious was the most powerful system in the psyche, and it contained the psychic traces of the human evolutionary past, including our prehuman ancestry. For Jung, the collective unconscious was a storehouse of inherited latent memories that predisposed us to react to the world in ways that were adaptive for our forefathers.

This sounds rather Darwinian, except that Jung populated the collective unconscious with “archetypes,” which sounded more like higher-order cognitive concepts than subcortical emotional action systems. Jung derived his archetypes from mythology, religion, alchemy, and astrology but also found them in dreams and art. The most basic of Jung’s preformed concepts was the mother. A baby’s perception of its mother was guided by its mother archetype, followed by its actual experiences with its mother. However, Jung also proposed countless other supposedly innate archetypes, such as father, child, wise old man, earth mother, god, devil, hero, trickster, birth, death, separation, initiation, marriage, power, and magic. In addition, Jung argued there were archetypes that had evolved into separate systems within the personality, such as the anima, animus, persona, and shadow, plus striving for unity, which included the self-concept and was often expressed through the mandala symbol.

Jung took his novel ideas and seceded from Freud’s inner circle, but he may not have escaped Freud’s Olympian stature. Jung attempted to move the Freudian system away from biologically driven conflict and development toward more cognitive motives and self-fulfillment goals. However, Jung was criticized for being mystical and outside the realm of what is needed to constitute scientific proof (as some would say, although science has only evidence for or against a theory). As such, Jung’s analytical psychology never had as strong an impact on the field of psychology as Freud’s psychoanalytic theories. In a survey of psychology historians, Freud was rated the most important psychological theorist, and Jung was rated 30th (Coan & Zagona, 1962). In a more recent assessment, Haggbloom et al. (2002) listed Freud as having more journal citations and textbook citations than anyone else, with Jung coming in at 50th and 40th, respectively, on these two lists.

One area that keeps Jungian ideas alive is the widespread use of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI; Myers & McCaulley, 1985), a popular personality assessment tool based on Jung’s theory of psychological types. Jung defined two major personality “attitudes,” labeled extraversion and introversion, and is credited with originating these terms. Extraversion is oriented toward the external, objective world, whereas introversion is oriented internally and subjectively. Complementing the two attitudes were Jung’s four psychological functions: thinking and feeling, and sensing and intuiting. The mother-daughter team of Katharine Cook Briggs and Isabel Briggs Myers turned the opposing pair of attitudes (extraversion/introversion) and the two opposing pairs of functions (thinking/feeling and sensing/intuiting) into three bipolar scales. To this they added a fourth bipolar scale, judging/perceiving, that was initially used to determine whether an individual’s primary function was judging (thinking or feeling) or perceiving (sensing or intuiting).

The MBTI test battery has been extensively studied, with many questioning how effectively it actually operationalized Jung’s theory but also acknowledging how difficult a task that would be. However, some data in a research paper by Robert McCrae and Paul Costa (1989) deserves attention because of its relevance to Big Five theory, covered in more detail in Chapter 12. McCrae and Costa compared the MBTI with their own personality assessment, the Neuroticism Extraversion Openness Personality Inventory (NEO-PI; Costa & McCrae, 1985), which is a widely accepted measure of the Big Five or Five-Factor-Model dimensions (namely,Extraversion, Neuroticism (the opposite of Emotional Stability), Conscientiousness, Agreeableness, and Openness to Experience). McCrae and Costa studied men and women and compared both self-reported and peer-rated NEO-PI data with MBTI self-report data. In all cases the four MBTI scales aligned the same way with the NEO-PI scales: the NEO Extraversion scale correlated significantly with MBTI Extraversion, the NEO Openness scale correlated significantly with MBTI Intuition, the NEO Agreeableness scale correlated highly with MBTI Feeling, and the NEO Conscientiousness scale correlated highly with MBTI Judging.

Consistent with how difficult it would be to encapsulate Jungian-type concepts in a conventional psychological test, McCrae and Costa suggested that the MBTI incarnation of Jung’s personality theory worked essentially like a Big Five personality assessment such as their NEO-PI, without the Neuroticism/low Emotional Stability dimension. That is, the MBTI had no scale measuring what McCrae and Costa called Neuroticism (the opposite pole of what the Big Five would call Emotional Stability). More important for our purposes, this means there is no provision in the MBTI for Panksepp’s three negatively experienced emotions, namely, RAGE/Anger, FEAR/Anxiety, and PANIC/Sadness, a finding further elaborated in Chapter 12. While Jung did include a shadow archetype, the trio of powerful negative primary emotions that are such key influences on personality and mental health were not well represented in the MBTI.

ADLER, HORNEY, AND SULLIVAN

Alfred Adler (1870–1937) was another of Freud’s early followers to leave his inner circle. He was an original member of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society, which at first met in Freud’s apartment, and he later served as the society president. However, like so many of the post-Freudian theorists, Adler rejected Freud’s strongly instinctual orientation. He broke with Freud in 1911, like Jung over the importance of sexuality, and began developing his own ideas, focusing on man’s social orientation.

Adler felt that our social nature was inborn, as was the major human motivation “striving for superiority” (what would now be called social dominance; for a discussion of the affective neuroscience of social dominance as a possible primary emotion, see van der Westhuizen and Solms, 2015). However, his social orientation toward personality led him to argue that it was not just instincts that explained human behavior but especially our goals that spurred our striving—our “attempts to express the great upward drive” (Adler, 1930, p. 398). These strivings often came from a sense of inferiority or imperfection ranging from a social disability to a child striving for a higher level of development. Thus, Adler’s theorizing moved even further away from a Freudian-styled personality based on instincts toward a more social, goal-oriented human nature. His thinking followed a post-Freudian pattern of becoming more conceptual and abstract as he attempted to explain human behavior from a clinical and educational perspective.

Karen Horney (1885–1952) was trained in medicine and psychoanalysis in Germany but moved to the United States in 1932, in advance of the wave of fascism. She became dissatisfied with orthodox psychoanalysis and was a founder of the Association for the Advancement of Psychoanalysis. She especially rejected Freud’s concept of penis envy and the Oedipus complex. Like Adler, she objected to the “instinctivistic” limitations of Freudian psychoanalysis. However, Horney further separated humans from other animals and wrote: “An animal’s actions are largely determined by instinct . . . and beyond individual decision. In contrast, it is the prerogative as well as the burden of human beings to be able to exert choice, to have to make decisions. We may have to decide between desires that lead in opposite directions” (1945, p. 23). Yet, she did reinforce the principle that normal and pathological behavior represented the same psychological dimensions and differ only by degree, and that “the difference, then, between normal and neurotic conflicts lies fundamentally in the fact that the disparity between the conflicting issues is much less great for the normal person than for the neurotic” (p. 31).

From her clinical experience, she defined a series of ten neurotic needs (Horney, 1942), sources of inner cognitive conflicts, which she argued the neurotic personality could not resolve realistically. She later organized these needs (Horney, 1945) into three orientations: moving toward people (affiliation and love), moving away from people (self-sufficiency and perfection), and moving against people (power, prestige, and achievement). More like Adler, she did not feel that conflict and anxiety were built into human nature but arose from difficult childhood and other social experiences. As such, Horney represented another step away from biological origins toward social-developmental influences and unique personal experiences. Hers was a less tangible, more conceptual theory of personality dealing mainly with the complex workings of the human mind.

Harry Stack Sullivan (1892–1949) was another psychiatrist who became dissatisfied with Freudian psychoanalytic theory. He was a little younger than Adler and Horney and born and educated in the United States, which may have made it easier for him to deviate even more from Freud in his approach to personality. Sullivan did not accept instincts or libido as significant sources of human motivation. Although he incorporated stages of development into his theory, “by the end of the ninth month the infant is manifesting pretty unmistakable evidence of capabilities of the underlying human animal for becoming a human being” (Sullivan, 1953, p. 150). In other words, in the process of maturation, humans gradually lose their pure biological status as animals and become social human beings.

In his interpersonal theory of psychiatry, Sullivan further adopted the position that personality was a function of interpersonal events and could only be observed in interpersonal situations: “The personality that can be studied by scientific method is neither something that can be observed directly nor something . . . of which would be any concern of the psychiatrist”; namely, “psychiatry is the study of the phenomena that occur in interpersonal situations” (Sullivan 1964, pp. 32–33). While his “dynamisms” such as “malevolence,” “fear,” and “lust” appear similar to Panksepp’s primary emotions of RAGE, FEAR, and LUST, Sullivan has carefully separated his dynamisms from any biological roots, for example, “Like any mammalian creature, man is endowed with the potentialities for undergoing fear, but in almost complete contradistinction to infrahuman creatures, man in the process of becoming a person always develops a great variety of processes directly related to the undergoing of anxiety” (Sullivan, 1948, p. 3). As such, Sullivan continues the pattern of generating more intangible constructs and moving further away from biological roots.

HENRY A. MURRAY

There is another personality theorist, we would like to include here, who took a rather different approach. Henry A. Murray, who wrote the epigraph for this chapter, largely ignored the dominant behaviorist zeitgeist of his time and heroically attempted to inject life and purpose into human personality by wedding McDougall’s broader instinct theory with Freud’s psychoanalytic linkage of unconscious motivation, early human developmental experience, and a narrower selection of primary instincts. Murray labeled his approach “personology,” which combined psychological assessments and clinical practice with an emphasis on the full understanding of each individual case within an environmental context.

Murray (1893 – 1988), a native of New York City, began his academic life as an undergraduate history major, graduating from Harvard in 1915. He then completed a medical degree from Columbia and an M.A. in biology from Columbia in 1919 and 1920, respectively. Eventually his interests led him to complete a Ph.D. in biology from Cambridge in 1927. Murray experienced a major life turning point when in 1925 he spent three weeks with Carl Jung in Switzerland and became inspired to pursue a career in psychology. Having been trained in medicine and biology, but drawn to psychology, family social connections may have provided Murray the opportunity to direct the new Harvard Psychological Clinic, which gave him the chance to pursue his psychological interests and provided the research for his most famous work, Explorations in Personality, published in 1938.

The zeitgeist Murray found himself in can be grasped in a quote by Dan McAdams from the foreword to the 2008 edition of Explorations:

Psychoanalytic ideas were new and exciting and were forbidden fruit in most proper departments of psychology. Indeed, American academic psychology in the 1930s could not have been more opposed to what Murray was trying to do at the clinic. . . . Watson had already established behaviorism as the dominant psychological ethos. . . . At Harvard, . . . E. G. Boring committed Harvard psychology to the most rigorous canons of empirical science. He took a jaundiced view of Freud, Jung, and Murray. (p. xii)

However, at the Harvard Psychological Clinic, Murray saw himself bringing together the dynamic assumptions of Sigmund Freud, other early psychoanalytic theorists, and William McDougall to put the direction, motivation, and adaptive quality into human personality that was lacking in the behaviorist approach (p. 37). At the clinic, he was able to draw together resources, including a team of researchers, to intensely investigate fifty-one individuals over a period of several years and draw his tentative conclusions laid out in Explorations. Like his predecessor Freud, Murray felt that the “physiologists” would someday in the distant future discover the true nature of “regnant” processes occurring in the brain and accepted this limitation. While he and his team could not directly observe these brain activities, they inferred that the personality expressions they observed were accounted for by brain processes (p. 45).

Murray is perhaps best remembered for his list of twenty manifest needs. For Murray, these needs were hypothetical constructs occurring in the brain that were associated with personality traits (Murray, 1938/2008, pp. 61–62). These twenty needs are listed in Table 5.1 along with Murray’s descriptions of associated desires and effects (paraphrased and extensively abridged), as well as the likely placement of six of Panksepp’s seven primary emotions.

While Murray rejected behaviorist stimulus-response descriptions, despite following the lead of McDougall and Freud by providing dynamic motivations for behavior, Murray did not base his manifest needs on instincts. Although six of these needs closely reflect Panksepp’s primary emotions, Murray did not consider these needs to be of an emotional nature. Indeed, Murray distinguished his manifest needs from McDougall’s instincts and wrote the following: “The instinct theory of McDougall emphasizes the impulsive, emotional type of behavior . . . found . . . very commonly in animals and not infrequently as reactions to sudden stimuli in adults (emotional needs). But, according to our experience, a theory of motivation must be carried beyond the primitive, impulsive (thalamic) level of action. It must be made to include cool, carefully planned conduct” (1938/2008, pp. 94–95).

With this statement, Murray anticipates the need to specify the level of personality behavior one is describing. While Murray prefers to focus on what we would call the tertiary level of behavior/psychology, we would argue that until there is a clearer understanding of personality at the primary level, our understanding of the tertiary, derived level of human personality will remain incomplete. In fact, we hold open the possibility that, despite the intense socialization characteristic of our species, human personality may routinely include more primary-level representation than many cognitively-oriented theorists would like to recognize.

| Table 5.1. Murray’s Twenty Manifest Needs Displayed in Murray’s Categorical Sequence | ||

| Need | Desires and Effectsa | Panksepp Primary Emotion |

| n Dominance | To control one’s human environment. To influence or direct the behavior and opinions of Os. | |

| n Deference | To admire and support a superior O. To yield eagerly to the influence of an allied O. | |

| n Autonomy | To get free, shake off restraint, break out of confinement. To resist coercion and restriction. To be independent and free to act according to impulse. | |

| n Aggression | To overcome opposition forcefully. To fight. To oppose forcefully or punish an O. | RAGE |

| n Abasement | To submit passively to external force. To accept injury, criticism, punishment. | |

| n Achievement | To accomplish something difficult, and attain a high standard. To rival and surpass others. | |

| n Sex | To form and further an erotic relationship. | LUST |

| n Sentience | To seek and enjoy sensuous impressions. | |

| n Exhibition | To make an impression. To be seen and heard. | |

| n Play | To act for “fun,” without further purpose . To laugh and make good-natured humor, even if slightly aggressive. | PLAY |

| n Affiliation | To enjoyably cooperate or reciprocate with an allied O. To remain loyal to a friend. | |

| n Rejection | To separate oneself from an inferior O. To snub or jilt an O. | |

| n Succorance | The tendency to cry, plead, or ask for nourishment, love, protection, or aid. To have always a supporter. | PANIC |

| n Nurturance | To give sympathy and gratify the needs of an infant or any O that is weak. | CARE |

| n Infavoidance | To avoid humiliation. To refrain from action because of the fear of failure. | |

| n Defendance | To defend the self against assault, criticism, and blame. | |

| n Counteraction | To master or make up for failure by restriving. To overcome weaknesses. | |

| n Harmavoidance | To avoid pain, physical injury, and death. To escape from danger or take precautions. | FEAR |

| n Order | To put things in order. To achieve cleanliness, neatness, and precision. | |

| n Understanding | The tendency to ask or answer questions, analyze events, and be interested in theory. | |

| Adapted from Murray (1938/2008, pp. 144–226). | ||

| a O = Object: any external entity (thing, animal, person) other than the subject; | ||

Before closing this chapter with a more detailed discussion of the three-level, nested hierarchy of behavior and psychology, which reflects brain evolutionary progressions, we note that the acceptance of Murray’s manifest needs is illustrated by the development of the Edwards Personal Preference Schedule measuring fifteen of Murray’s needs (Edwards, 1954) and in the ongoing use of Douglas Jackson’s (1929–2004) more recent Personality Research Form, which includes measures for all twenty of Murray’s manifest needs (Jackson, 1974). At the Harvard Psychological Clinic, Murray and others also developed the Thematic Apperception Test, a projective assessment designed to measure a person’s underlying motivation, which is still in use and being revised (Gruber & Kreuzpointner, 2013).

THREE-LEVEL NESTED BRAINMIND HIERARCHY

Importantly, we are not arguing that any of the discussed theorist’s ideas are not valuable. Many of their books, especially those of Horney and Sullivan, were published by W.W. Norton & Company and are still in print. What we are saying is that there needs to be a way to have a clear conversation about such clinically derived ideas that are often highly conceptualized and difficult to test in humans, let alone in animal models, without diminishing the importance of the primary emotions that we feel they are built upon and embedded within. This is where the three-level nested hierarchy comes into play.

The Three-level Nested BrainMind Hierarchy (NBH) illustrates how each evolved primary-process emotion sets up secondary-process learning and, furthermore, is embedded in tertiary-process cognitions (see Figure 5.1). The red squares represent the primary-process emotions; the blue ovals depict the secondary-process learning; and the purple rectangles illustrate tertiary-process thought and language (see color insert). The shapes along with upward and downward pointing arrows are intended to model that (1) lower level brain functions provide bottom-up influence on higher levels and are integrated into higher-level brain functions and that (2) higher level brain functions eventually exert top-down activation, inhibition and regulation of lower levels. Each primary-process emotion has a distinctive affective valence—that is, each has either a positive rewarding or negative punishing experience that not only guides decision making in survival situations but also promotes learning that allows for modifying these primary ancestral action systems to better meet current environmental demands. Experimental psychologists have traditionally called these evolved affective brain processes unconditioned stimuli and unconditioned responses. Indeed, FEAR and the homeostatic affect of HUNGER have been the affects that allow for diverse “reinforcements” (as discrete “objects” in the world, for example, foot shock and food) to be used by experimental psychologists to study learning. One of the functions of the primary emotions and other affects seems to be in guiding the organization of learning and memory within their respective affective spheres. As such, the primary level coordinates learning at the secondary level, which after the learning can, in turn, provide top-down adaptive modifications of the primary-level response systems (bottom arrows in Figure 5.1).

Further complexity is added as lower-level processes guide the maturation and development of tertiary-level cortical functions. We hypothesize that the functionality of the primary and secondary processes becomes represented functionally and symbolically (especially in humans) and embedded as acquired abilities in the tertiary (large cognitive/information-processing) mind. Moreover, the maturing tertiary mind, which is largely (but not exclusively) neocortical, is gradually able to add increasing sophistication and regulation to our responses to life events (top arrows in Figure 5.1). However, even as the tertiary mind gains the capacity to provide top-down cognitive regulation to our everyday psychobiological responses, our cognitive mind may still become subservient to the primary emotions when bottom-up primary affective influences suddenly appear as more challenging issues are confronted and experienced, leading at times to extreme emotional sensitivities—namely, affective states of mind that can trigger pathological displays. Thus, two-way, circular causation becomes an adaptive feature of the human mind and perhaps of mammalian minds in general, with bottom-up development and learning initially leading the way, and top-down regulations and reflections becoming part of the healthy mature (or, in extreme cases, pathological) BrainMind apparatus. The challenge of biological psychiatry and psychotherapy is to facilitate reorganization of such BrainMind dynamics.

Figure 5.1. Nested BrainMind Hierarchies: Two-Way or Circular Causation. The three-level Nested BrainMind Hierarchy summarizes the hierarchical bottom-up and top-down (two-way or circular) causation proposed to operate in every primal emotional system of the brain. The diagram illustrates the hypothesis that in order for higher MindBrain functions to mature and function (via bottom-up control), they have to be integrated with the lower BrainMind functions Primary processes are depicted as red squares; secondary-process learning as blue circles; and tertiary-level processes by purple rectangles. This coding conveys the manner in which nested hierarchies integrate lower and higher brain functions to eventually exert top-down regulatory control. Adapted from Northoff et al. (2006). See insert for color.

SUMMARY

With the three-level Nested BrainMind Hierarchy (NBH), we have a coherent BrainMind conceptualization—a developmental-functional way of thinking and discussing the cognitive complexities featured by the more strictly psychological, conceptually-oriented personality theorists while still maintaining explicit links to our lower-level primary influences, which are not simply given residual status but offer a bridge to a robust animal neuroscience understanding of primal emotions that can lead to novel therapeutics (Panksepp, 2004, 2006, 2015, 2016; Panksepp et al., 2014; Panksepp & Yovell, 2014). Among Murray’s list of twenty manifest needs, some, such as aggression, would seem to retain their primary-process emotions more obviously, while others seem difficult to parse in terms of primary emotions. We must also recognize the difficulties in parsing the tertiary-level mind in the same way that animal research has allowed comparative neuroscientists to probe the primary emotions through animal brain research (Panksepp, 1982, 1998a).

One question is whether the higher-level mind can create emotional feelings and novel higher-order emotions that are not based on evolved emotions in the subcortical brain. Whether the mind can create emotional subtleties beyond the raw subcortical emotions remains an open question. For instance, are there demonstrable neuroscientific differences between empathy and sympathy, or are they conceptual nuances on a theme only represented in our abstract thoughts that cannot be differentiated in the brain? The NBH way of seeing the brain and mind would suggest that some element of a primary emotion would always be present in our tertiary thoughts, although the variations possible at the secondary level might be virtually limitless.

The importance of the NBH becomes apparent as we discuss additional personality models in future chapters. For now it may be enough that the NBH can provide a richness and a level of integration to the discussions of personality theory that does not require Freud, McDougall, or Murray to be absolutely correct. Perhaps the NBH provides a way of thinking for discussions in which our evolved neurobiology, our capacity for cultural adaptation, and varying levels of individual maturation and adaptation can be reconciled.