If you are going far for a class, or you will be taking care of more than just one rifle, something like the Otis team kit will serve you well.

This is the level of cleaning you do in a class or during a weekend spent burning through more ammo than you can afford or find at the local big-box store to replace. The idea is simple, you aren’t going to detail strip and lovingly scrub and re-lube all the parts. You want to keep the rifle running and you want to do so without spending any more time at it than you need to.

We have two approaches and two levels of cleaning to consider. The approaches are Neo-brutal and Cautious-brutal, and our two levels are “break for lunch” and “day is done, get ready for tomorrow.”

Let’s mix and match, shall we?

You’ve got an hour, maybe less, and in that time you have to hit the restroom, get lunch, slather on sunscreen/insect repellant, re-hydrate so you don‘t pitch over face-first into the dirt in the afternoon, dive into the vehicle to get more gear or ammo, and do some cleaning of your rifle. All the rest, you have to figure out on your own. Here, I’ll just talk about the rifle cleaning.

“Neo,” a prefix from Neanderthal meaning before modern, and not as used in Neolithic. “Brutal” would be to simply neglect it until something breaks or stops working, and then fix it. We’ll go up a step in caveman hierarchy, and actually tend to a few, very few, things.

You unload (if the class or range day is at a “hot” range) and pop open your rifle. Pull out the bolt/carrier group and set it aside. Take your chamber brush on its “T” handle and scrub the chamber and locking lugs. Poke a patch, wet with either oil or copper solvent, down the bore. Set the upper aside. Use your plastic brush to knock off the bigger chunks of carbon from the bolt and carrier. Wipe the bolt and carrier with a shop cloth. Lubricate the extractor and ejector. Squirt some oil back into the bolt at the carrier tunnel, and into the gas port holes on the carrier.

If you have the time, energy and paper towels, wipe the gunk out of the upper.

Drop some oil onto the springs of the fire control parts of the lower, and the disconnector pivot point.

Slap it all back together, and get on with the lunch break.

“But, but, but!” I know, you’ve been told to run the AR dry. Almost completely B.S. Unless your class is in the arctic, in the winter, you need lubricant. You’ve also been told that the powder residue, mixed with oil, will turn into a lapping compound and grind your rifle into nothing. Again, B.S. If you go to the auto parts store, or browse Brownells, you will find lapping compounds. You will not find one that is marketed as “a top-quality mixture of carbon/powder residue in grease.”

Is the carbon residue in your receiver awful stuff? Yes it is, but it isn’t valve-grinding compound. Are you using axle grease to lube your rifle? (I hope the answer to this is “no,” but you never know.) If not, the lubricant is not holding the suspended particles against the surface, they are simply sloshing around in there, kind of like the particles of your lunch, in the glass of water you’ve been drinking. They aren’t hard enough, and not pressed firmly enough to the surface, to do any grinding.

So, scrub the chamber, knock the big chunks off, and hose it with oil. When you get to the point that you have enough oil in there that you are splattering the shooter to your right, you’ve over-done it. (He will probably say something.)

I have gone through multiple classes, from several days to week-long classes, doing nothing but this. As long as you get the build-up out of the chamber so you don’t get a round wedged in there, and you keep at it with the lube, your rifle (assuming it is properly-built) will keep on running.

This level of maintenance has also been described as emergency cleaning, fighting clean and combat clean. Oh, and in a pinch, if you find yourself lacking lubricants, don’t despair. Is there a vehicle nearby? One you can get under the hood of? Great. Use the end of the dipstick, or the dip from the transmission, to apply lube. Motor oil, even used, and transmission fluid are both great lubricants. In fact, a lot of the pricey, “special” gun lubes you can buy in cute little one-ounce bottles are repackaged motor oil or ATF, and some even have a special dye in them to make them an attractive-to-shooters color. If you have a plastic bottle of synthetic motor oil, you are good for a long time.

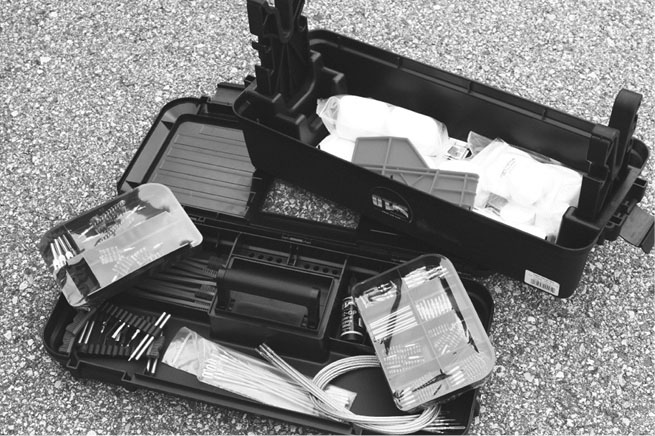

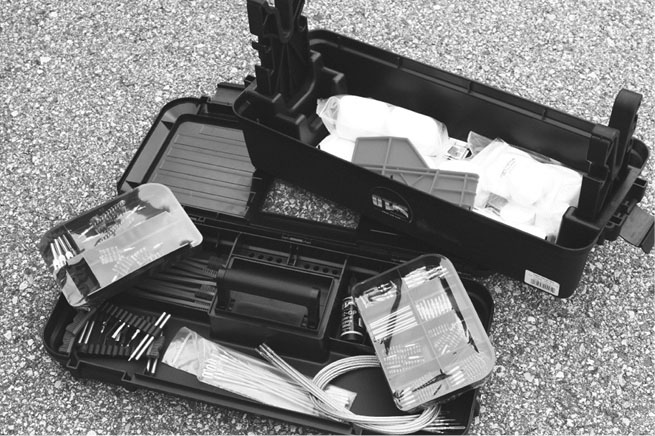

If you are going far for a class, or you will be taking care of more than just one rifle, something like the Otis team kit will serve you well.

Would a Sergeant or inspecting officer, military or law enforcement, have an attack of the vapors if they looked at your rifle, in such a state? You bet. Will it keep working, despite their protestations? Surely.

Here, we’re taking a bit longer, because we can, because we have the time or because we just can’t stand the thought of “abusing” the rifle we are using. A quick clue: if you are in a class where you are shooting through 1,000 rounds in a few days, or 1,500+ in a five-day class, you are abusing the barrel more from shooting it than from not cleaning it. The heat is worse than the wear. And yes, I realize that in the “new normal” of expensive ammunition and limited supplies, blasting a thousand rounds in a few days can be painful.

For Cautious-brutal, you start with the Neo-brutal and add a few steps.

Once you have it apart and chamber-brush the chamber and locking lugs, push a copper-solvent patch down the bore and get out a roll of paper towels or a can of aerosol cleaning solution. Wipe the interior of the upper with the paper towels. If the range has the gear, or lacks concern for the environment, hold the upper, muzzle up, and spray the interior with the aerosol. Spray with lube and wipe with paper towels. Ignore the exterior.

Do the same with the bolt/carrier assembly. Knock the big chunks off, aerosol spray, lube and wipe.

Do this over a trash can, if the range has one.

Spray the lower, holding it over the trash can. Lube.

Above: The Otis team kit has multiple brushes, in a variety of calibers, and no end of pull-through cleaning cables. Below: If you are going to have the means to clean a bunch of rifles, you’ll need all the adapters for patches, brushes, etc. Otis has you covered.

Push another patch down the bore, make sure everything is properly lubed, and re-assemble.

Now, in using the aerosol spray can, you are not being gentle or conservative. You are not looking to spray, then wipe gunk off. You are hosing the gunk off with the spray cleaner and letting it air dry.

Those who have been to a class know the drill: class is over, everyone throws off their gear, cases the guns, throws it all in the car, and disappears to the hotel to clean up and get dinner before collapsing for sleep until the next day. You can’t.

The end-of-day Neo-brutal is simply the Cautious-brutal with one extra. After you’ve done the field-strip, hosing, knocking of carbon chunks and re-lubing, you then take a clean and dry cloth (a red shop cloth is perfect) and wipe the mud, dust, dirt and whatever else off the exterior. You also check to make sure everything is still tight and correctly-located.

Then you put it in the rack and let it sit there for a few minutes while you gather up your gear, pack the vehicle and get ready to leave. Then, check your rifle to see if any oil has oozed out, wipe it off, put the rifle in your case, in the car, and drive off.

One thing I’ve learned to do, at the end of the day and before leaving the range to the hotel, is put my empty rifle case on the hood of the car. That way you can’t drive off, leaving your rifle in the rack oozing oil.

At the hotel, haul the gear out, lock the rifle case to something solid, take a shower, get dinner and then collapse for the night.

Obviously, you do all the Neo-brutal, end of day steps, but then you do another check once you get back from dinner. (A note; a training class is time for you to train, to learn and to work on your firearms skills. It is not time to socialize. Do not drink. If you have a drink at dinner, there is no Cautious-brutal cleaning session for you, post-dinner. There is nothing to do with firearms until the next morning. Absolutely nothing.)

Once you get back, unlock the case and haul the rifle out. Keep all ammunition and loaded magazines away from your work area.

Use your shop cloth to wipe the exterior. Check the tightness of anything bolted on, such as BUIS, optics, sling hardware, etc. Inspect your sling, to make sure it is secure and un-worn. If frayed, replace it. Separate the upper and lower and give them a quick once-over.

Inspect your charging handle. Make sure the front end isn’t peened or cracked. Check the upper, make sure the barrel is tight and the handguards are secure.

Inspect the bolt and carrier. Make sure the firing pin is correctly installed, and that there are no obvious cracks in anything.

Look inside the lower, and make sure your hammer and trigger springs both have two legs and that they are properly located.

Put it all back together, in the case, and go to bed. You have a long day ahead of you.

The idea is simple; we do everything that keeps the rifle running, and we don’t do anything that would take more time, effort, supplies or daylight.

This is a cleaning regime I learned shooting at Second Chance. For those who have read me on the match, feel free to skip ahead. (There will be a test. If you fail, don’t blame me.) The match was nine full days, with as many as eighteen different events you could enter. My maximum ammo consumption happened in the end days, the last seven or eight years of the match. My ammo load-out, for the drive to Central Lake, was something like two eight-pound powder tubs, empty of powder (loaded into ammo) and filled with reloaded .223 ammo, on the order of 3,000 rounds. Plus extra, factory ammo, just in case I ran over and needed to keep shooting. Two cases of 12 gauge buckshot, two cases of 12 gauge slugs. Another eight-pound powder tub, filled with reloaded 12 gauge, “warm-up” ammo. Two .50 BMG ammo cans filled with .45 ACP ammo, two more filled with 9mm ammo. One .30 ammo can filled with .38 Super ammunition, and another filled with 9mm ammo. A “brick” of .22LR.

The guns consisted of three AR-15s, three 12 gauge shotguns, three .45 ACP pistols and one .45 ACP revolver, two 9mm pistols, a .38 Super pistol and a .22LR Ruger 10/22 rifle. Complete with a bushel basket sized box of magazines, and another of cleaning supplies.

And to be clear, I was not going to spend a moment longer than necessary keeping them any more clean that they needed to be to work. They were not going to be lovingly stripped down to the last part, scrubbed, wiped, lubed and reassembled. I would be spending all my time shooting and warming up to shoot, and time spent cleaning was time wasted from sleeping or shooting.

So the two cleaning procedures are designed to keep a rifle running, regardless of the volume of shooting or training you are doing. (Modified for the specifics of the firearm involved, they also work for handguns and shotgun.)

They will not put you in the good graces of the training authorities if you are in some official training system. To be plain, The Sergeant will not be happy.

However, most training, military or law enforcement, is not the least bit concerned with actual function, marksmanship or gun handling. It is to reinforce rules of engagement, practice reaction drills, and satisfy training-time requirements. In those circumstances, firearms cleanliness is the only thing a trainer can “gig” you on, and so they will.

Now, a steady diet of this kind of “cleaning” will probably shorten the service life of your rifle. However, and not to contradict or negate the advice above, anyone who sends a rifle through 8,000 rounds continually in this state deserves to have a couple of thousand rounds worth of service life deducted from the total. But, your skills will be all the better for the “loss.”

This is for when you and your rifle are working or training. Once you’re done, you do a complete and thorough cleaning, as detailed in the next chapter.