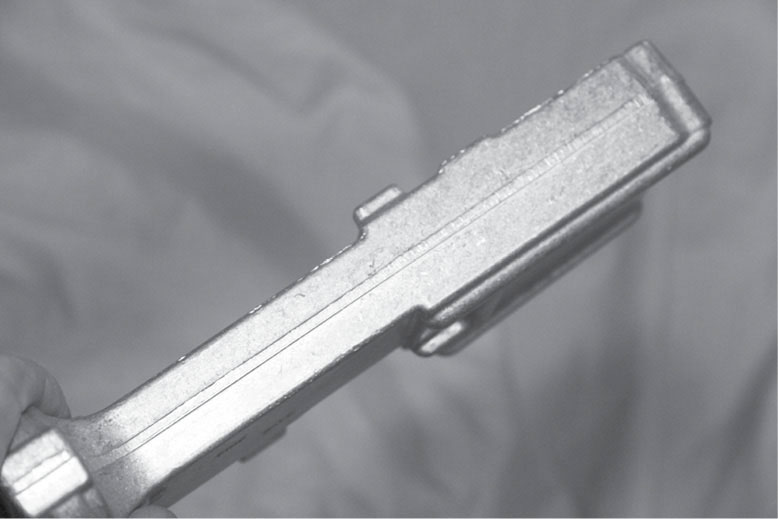

An AR hammer on top, with the firing pin catch notch, and an M16 on the bottom, with the rounded corner. Both work just fine.

If you let yourself be influenced by the news, pundits or politicians, you’d believe that you’d have to hold regular exorcisms of your AR just to keep it from coming for you in the dark of night, evil thoughts ablaze. It is, however, merely an inanimate object, and can’t do anything on its own.

What it can do, however, is get you sideways with the law if you aren’t careful with your choices or actions. The very modularity of the AR can result in the wrong parts being bolted on (by you or someone else) with the result of a legal violation.

Out of the box, you’re highly unlikely to run into problems. The people who manufacturer or assemble ARs for a living know what is allowed and what isn’t, and don’t want to get in trouble. It is when owners start changing things that trouble can ensue.

An AR hammer on top, with the firing pin catch notch, and an M16 on the bottom, with the rounded corner. Both work just fine.

There are two arenas where you can get into trouble, state/municipal and federal. Since the feds, curiously, are clearer and easier to describe, we’ll cover them first.

Your AR, for the purposes of categorizing at the federal level, falls into one five slots: rifle, SBR, machine gun, pistol and “any other weapon.” When you are discussing the law, you cannot mix terms. A federal definition may have little or nothing to do with a state definition, and vice-versa, and you will only confuse things if you are not clear.

The AR, due to its modularity, allows for mix-n-match combos. An assembled upper or lower that does not have a mate is termed an “unassigned” upper or lower. If you have one lower and two uppers, the uppers are clearly assigned to that lower. If you have two lowers, and three uppers, and you leave them as two assembled rifles and the extra upper, that third upper is an unassigned upper. Throw an un-assembled lower in the safe, and some spare barrels, and you now have a potential minefield. Which upper, currently not on a lower, goes with which lower? It can matter, as we’ll see.

A rifle, in federal terms, is an AR with a barrel longer than 16 inches, and an overall length greater than 26 inches. This is easy, as any buffer tube makes an AR carbine thirty inches or more in length. Overall length is easy, measure the length, parallel to the bore, from one end to the other. Barrels are measured by the distance from the bolt face when closed to the forward-most part of the barrel that is permanent. Keep that in mind – permanent. Your flash hider does not count for overall length unless it is permanently attached. It doesn’t matter how tightly you have it torqued on. The ATF does not view any thread-locking compound as being permanent, regardless of brand or strength rating. Soft solder is not permanent. They will not settle for anything less than a high-temperature silver-solder job or welding.

AR or M16? An M16 trigger, which to be used in an AR (semi-auto-only) rifle you should weld or silver-solder the rear slot closed.

This matters because there are a lot of barrels to be had at gun shows, over the internet and at the gun club. Most of them will be 16, 18 or 20 inches in length. However, there are always “deals” to be had on shorter ones, alleged 14.5-inch M4 “takeoffs” (the government does not yank off perfectly good barrels or sell them by their weight as scrap steel) and 11.5-inch “commando” barrels of dubious origins.

So, your smokin’-hot deal on an M4 barrel that is 14.5 inches long can get you in trouble. If you install it on your rifle/carbine, it will be too short to be legal. You have to permanently attach a flash hider or suppressor mount to it, one that adds at a bare minimum of 1.5 inches to the barrel’s length, better a full two inches. If you do not, you cannot use it to build an upper, even an unassigned one, because it is the work of a moment to slap it onto a lower and make an unlawful rifle.

You can own the spare barrel at 14.5 inches, but you cannot assemble it to an upper. In fact, it would be prudent to not own that barrel and an un-assembled upper. The ATF views such things through the legal lens of “constructive intent.” You owned all the parts to make a prohibited rifle, you hadn’t (yet) assembled them, but you could have in five minutes. More on this is a bit. Just keep in mind, you do not want prohibited parts floating around your gun room.

A short-barreled rifle is a semi-automatic rifle with a barrel shorter than 16 inches. To own one you have to do the NFA-34 dance, as an SBR is treated as if it were a machine gun. (It isn’t a machine gun, and you must also be clear on that.) You have to apply to the ATF to get the Tax Stamp by paying the $200 tax, and then be happy. There are, however, a few things to keep in mind.

Federal law does not trump state law on this, or any of the following categories. Just because the feds license it, if your state does not permit it, you can’t have it.

Also, the Tax Stamp/SBR is for a particular rifle, the one detailed on the form you submitted. If you SBR’d your AR, the rifle known as Bob’s Guns #123, then that rifle is the SBR. You cannot simply plop your short-barreled upper onto any other AR you own and call that one your SBR for the day. This applies even to police departments, something it has been difficult to get across to some administrators. The SBR is the serial-numbered lower listed on the Tax Stamp, and only that one can be the recipient of a short-barreled upper.

If you, the departmental armorer, are instructed to build up any old lower as the “departmental SBR” because the department has received permission to build an SBR, or you are ordered to do something similar, something you know to be against the law, I offer my condolences. Your choices are simple: tell the Sergeant. Deputy Chief, Chief, Sheriff, whomever, “no” and risk a career-interrupting event, or obey the order knowing you are breaking federal law. One of those choices will land you in prison.

These are barrels too short for a regular rifle or carbine. They are SBR or pistol barrels, and you’d best have the right paperwork and firearm to own such a barrel.

The safe way to own an SBR is to keep the SBR upper on the SBR lower all the time except when cleaning. And not have other rifles apart for cleaning, on the same bench, that aren’t SBRs. And, if you have several uppers for that lower, keep them all in one large hard-sided case. And never leave an unassigned lower lying about.

For departmental armorers, it would be prudent to somehow mark the upper with the serial number of the SBR lower it is assigned to. That way there can be no confusion, and if a superior orders a bad thing, you have the “the uppers and lowers are serial-number matched” as a temporary dodge until you can get the departmental attorney on your side.

A hazardous time for SBR owners is a fun day at the range with friends. One of your buddies thinks, “Hey, that SBR thing is cool, I wonder how that would work on my lower?” When you aren’t looking, he swaps your SBR upper onto his lower to try. That, my friends, is a federal felony, an unlawful construction, and you could get in trouble. Is the law irrational and stupid? Yes. But it is also very clear, and you should know better.

You apply to the ATF to have your rifle SBR’d. (And yes, the term has been used enough now to be a verb.) You get approval, buy the parts, build the rifle and mark it according to the regs. (Yes, you have to mark it, as the builder of the SBR.) You shoot it for a while, then get tired of the whole thing and decide you want out.

In order to transfer it to your buddy, he has to apply for his own Tax Stamp, pay his own $200 and receive approval. Then, and only then, can you transfer it to him. Or, you can sell it to a dealer in such things, known in the trade as a “Class Three” dealer. He does not have to pay the transfer tax, but the person who buys it from him does.

This is an M16 (an A1) and will always and ever be so. The ATF rule is simple; “Once a machine gun, always a machine gun.” Were this transferable, it would be worth close to $20,000. It isn’t, and thus is worth ten years in Ft. Leavenworth.

You could just re-build it with a 16-inch or longer barrel and ignore the SBR status it still has. That would be fraught with peril. If you take your still-SBR-status AR across state lines without filing the correct travel papers, you’re in violation of the law. And if you forgot it was still an SBR and sold it, the new owner would be in violation (actually, both of you) for owning an SBR for which he hadn’t paid the tax.

You can, however, simply write to the ATF and ask that your rifle be removed from the registry. You do not get your $200 back, but you now have a plain rifle again.

This is a select-fire AR, called an M16, and you buy it through the same process as the SBR: Tax Stamp, $200 tax, license. As a machine gun, it can be whatever you want it to be. You can put an SBR upper on it without any extra paperwork, as the machine gun status trumps the SBR status and paperwork.

There is no part on this rifle that meets mil-spec. Everything on it is better. Also, there is no need to use anything M16-ish inside, as it would actually hinder performance. Buying M16 parts for a rifle like this is false economy.

If an MG is superior to an SBR, why go the SBR route? Cost. The current cost of a transferable M16 is in the region of $15,000. That’s right, a transferable M16 runs as much as the cost of a small car. The NFA Registry for machine guns was frozen in 1986 and no new ones have been built since. SBRs have not been frozen, and buying one simply costs you the price of an AR, the $200 tax and the conversion costs by you or your gunsmith.

If the numbers have been frozen why can you see them all over the internet, in videos? And how do police departments have them? The first part is simple: a manufacturer built them. You can, if you wish, apply for a manufacturers license, and begin building select-fire AR-15s. You cannot, however, sell them. They are not transferable except to police departments, the group excepted from the ban on newly-made machine guns.

Oh, and if you do decide the expense of a manufacturers license is too much, all your M16-like ARs must either be sold to another manufacturer (and they will offer a dime on the dollar for them, at your original cost) or turned in to the ATF for destruction. That’s a hobby best left to lottery winners.

The best way to store your transferable M16 is in a locked, hard-sided case, in your locked gun room, in the locked safe, with all the uppers it uses. In the case of a question, you want there to be no uncertainty; the M16 is as secure as the launch codes for the nukes.

Oh, and don’t be a moron – insure it for full value.

An AR pistol is one that does not have a stock. As a pistol, it can have a barrel of any length, including less than 16 inches. However, simply sliding the stock off of your buffer tube does not make it a pistol. The defining characteristic of an AR pistol is that it has a buffer tube which lacks any provision whatsoever for attaching a stock. It is a bare tube, lacking both the rear, threaded hole to bolt on an A1/A2 stock, and the lower spine to adjust a slider for the telescoping stock.

To make an AR pistol, you either buy one that was made that way from the start, or you build from a bare lower that has never been a functioning firearm. You assemble it with the pistol buffer tube, and it is then a handgun. (It is also a handgun under state law, and you’d better be covered there, too, or you’re in trouble. Make sure you know your local laws and follow them.)

If you decide that you are tired of an AR pistol, you can then make it a rifle. You cannot, however, make it a rifle with the shorter-than-16-inch pistol barrel on it. And it would probably not even be smart to keep the shorter pistol barrel. Sell it, buy a 16-inch barrel, then re-build as a rifle. Can you re-re-build it as a handgun again? I’d say no, but some say you can. No one really knows, because the ATF hasn’t issued a ruling nor have the courts weighed in on it. They’ve weighed in on a different, similar case, but a similar court case may not impress them. They would insist on a particular court case. The question here is, do you want to be the one in the middle of that new, particular, court case? I thought not.

It is common to mark an AR handgun thusly, even though you don’t have to. Well, you might by state law, but not for the feds.

AR handguns are fun. A pain to get and keep running, but fun. Just make sure you keep the pistol upper on the pistol lower, and everything will be fine.

Be smart and if you decide to go back to an AR pistol, start over with a new, bare, lower. The AR pistol is a one-way street, pistol to rifle, but never back again. Not until the law is clear.

“Any Other Weapon” is the catch-all term that the ATF uses to sweep up everything that doesn’t fit neatly into the other descriptions. Actually, they have been forced into it by moronic legislators who really don’t know anything about firearms, but who have passed laws anyway. You see, by the “reasoning” of some lawmakers, any handgun with a vertical foregrip is a particularly evil and deadly firearm. You can put that foregrip on any of the other categories of AR – rifle, SBR, machine gun – but not onto a handgun. If you do, it is an AOW. The good news is that the Tax Stamp to own an AOW can be as little as $5.

Let’s go all “Breaking Bad” here. You have this kewl idea for a Halloween party: you get all the gear, all the precursor chemicals, and you find the formula for making crystal meth. You have all your guests show up in hazmat suits and wear respirators, and you play episodes from the Blu-Ray Collectors Edition, Directors Cut DVDs in your collection. Cool party, eh? Yes, and a perfect example of constructive intent. You didn’t have the intent to make it, but if anyone mixes two chemicals, you are then in the process of making crystal meth. You’re in hot water.

The firing pin area has been altered over the years. The M16, on the left, has a shrouded firing pin. The AR-15 on the right is open, to prevent tampering and conversion.

So, don’t go buying all the parts needed to be making yourself an SBR (for example) and leave them lying about. The process of getting an SBR takes some time, and you’ll have plenty of opportunities to acquire the parts you need once the approved Tax Stamp returns. Plus, if you are having someone build it for you, they won’t even start until they see your approved form. If they do, and you get denied, they are in possession of an un-approved SBR, a felony.

Similarly, if you plan to build an AR pistol, don’t collect the parts until you have a lower on which to assemble them. And then, keep all the parts together in a locked case, box, whatever. You want there to be no misunderstanding if someone sees the parts.

How could that happen, you ask? Hmm, let’s see, how can people be in your house? Guests at a party, and you forgot to lock the spare bedroom, the one where you do your gun work. Or, guests at a party and a fight breaks out. Or an accidental fire. Or a heart attack. The resulting police or fire response puts your house under scrutiny. If there is a fire, the firemen are not going to respect locked doors in their quest to keep the place from burning to the ground. What has been seen cannot be un-seen.

Save yourself risk, heartache, legal expense and perhaps a “vacation” in orange. If you’re going to do this, do it right.

The simple, easy, and unlikely-to-get-you-in-trouble answer is none. The ATF doesn’t really care how many parts you have, what they care about is, “does it act like a machine gun?” The big question for a long time was the carrier. An M16 carrier is heavier than the AR-modified ones, and the extra weight does have a functioning advantage. The ATF has come out with the opinion that the carrier is now no big deal, and now some AR manufacturers ship their semi-auto only ARs with M16 carriers. The rest of the parts are still problematic.

The hammer, trigger, disconnector and safety/selector are all relatively common parts. You could if you wanted, acquire a full set of M16 internals, but why would you want to? Back in the early days of AR building, the M16 parts were far more common than the AR-15 parts. (Only Colt made AR-15 parts. Military surplus parts were all M16, and common and cheap at gun shows. A set of proper Colt AR-15 parts could cost you four or five times as much as the mil-surp set.) It was not uncommon for someone to buy the M16 parts, assemble a rifle and make sure it worked correctly, then de-fang the M16 parts. That is, grind off the extra hooks, tabs, etc. that made them M16 parts, and to solder-up the gaps in the selector so it wouldn’t work except as semi-auto parts. Why assemble first, then modify? If a part was defective, you could go back and exchange it. If you had already ground on it, the seller wouldn’t take it back. This is now a dangerous practice. Imagine trying to explain to a jury of non-gun people (all the gun people would have been bounced off the jury by the Prosecution during interviewing of prospective jurors) just what “un-M16ing” a part entails, how it works, and why you would bother. Especially since you can buy perfectly good, semi-auto-only parts these days just about everywhere, and for much the same cost.

A friend of mine, a law enforcement trainer, has told me a cautionary tale. (He tells it in every one of his classes.) A long-serving command staff police administrator was accused of selling guns out of the evidence locker to gang members. Of course, any reasonable person who believed the “confidential informant” would simply get a warrant, and then go down and conduct an inventory of the evidence locker to verify the truth of this rumor.

No, the feds raided his house and confiscated his guns. Finding no evidence-locker guns, they were in a bind. So, they latched onto a competition AR the officer had built, built exactly as described above. Through all kinds of trickery, the ATF was able to get the rifle to fire two rounds on one trigger pull. Ah-ha! A machine gun. It took (and this was a couple of decades ago) several years and fifty thousand dollars to fight and win.

An array of disconnectors. On top, an M16, middle an AR-15, and bottom an early Colt AR-15, that proved to be troublesome for Colt. You can make the top one like the middle one by simply chopping off the extra length.

More recently, a National Guard sergeant in a Midwestern state was run through the same wringer, but did not win, and served time in prison.

It would be prudent to not mess with M16 parts, unless you actually have an M16. But, you can do it properly, so we’ll look into that.

In the manufacturing process, some of the parts in your AR-15 were made as M16 parts before the manufacturer took one more step and turned them into AR-15 parts. The hammer and carrier are two common ones. I’ve also seen disconnectors that were M16 parts in the manufacturing plant, until the last step to make them AR-15 parts. So, in the following example, you are doing pretty much what the manufacturers are doing in many cases.

The parts you need to know about are hammer, trigger, disconnector, safety and receiver auto-sear. Of the five, if you ever encounter a receiver auto-sear, get rid of it immediately. I’ve been accused of being a bit paranoid about this, but it serves no useful purpose to the owner of an AR, a semi-auto-only rifle, and can only get you in trouble.

The hammer of an M16 has a square lump on the top rear of the hook. This lump, or hammer auto-sear, connects/engages the receiver auto sear I just told you to get rid of (And you did, didn’t you? Didn’t you?) when the M16 is set on Auto or Burst. To remove the hammer auto-sear (if you insist on keeping this particular hammer), you simply use a bench grinder to grind it off. Grind it completely off. Don’t get cute, and just grind off “enough” or leave some there. Grind the hammer surface to a flat surface, just as the manufacturers do.

The various bolt carriers. Left to right, the fully-shaved Colt, the semi-auto AR-15, and the M16.

Disconnectors are flat pieces of heavy gauge sheet steel, stamped or fine-blanked out of coils of steel. The M16 disconnector has a longer tail, and the tail engages the M16 safety/selector. All you have to do is cut or grind off the tail and it is now an AR-15 disconnector. Again, don’t do “just enough” or simply lower the tail, there is no advantage to leaving any of it there. Grind it off. You can do this with a bench grinder, or clamp the disconnector in a vise and use a cut-off wheel. I’ve even seen people who dealt with M16 disconnectors by clamping the part in a big vise with just the offending part sticking up, and using a big hammer to bend it until it broke off.

Carrier mods have created all kinds of variants. This is a shrouded-pin, common on M16, trimmed-back autosear shoulder (and thus semi-auto only) carrier, that is common these days. I don’t know of any place where this would get you into trouble.

If there had been an auto-sear lump on it, this is where it would have been before the manufacturer ground it off to make it an AR-15 hammer.

Triggers, too, start as M16 triggers in the manufacturing plant, and the last step there is to make them into AR-15 triggers. The trigger has a slot in the middle, where the disconnector rides. The M16 trigger is open at the back of the slot. That opening allows the longer tail of the M16 disconnector to engage the safety. To convert it back to an AR-15 trigger, you have to weld or silver-solder up that opening so an un-altered M16 disconnector no longer fits. A lot of people don’t bother, and if you do either in a ham-handed way you can ruin the heat-treatment of the trigger, and it will wear and fail.

Triggers also come with two locations for the disconnector spring, and the two types of two-spring triggers are not the same. When Colt first made semi-auto AR-15s, they radically modified the disconnector. They changed the location of the disconnector spring, and they moved it too far. To correct that, and allow for future parts use, Colt made triggers with two spring holes. Later, the Burst trigger also came with two diconnector spring holes. The difference is, the standard AR-15 two-spring trigger has the same narrow slot as the M16, and the holes are directly in line. The Burst trigger has a much wider slot, and the spring holes are offset. You can’t un-Burst the Burst trigger, so you should ditch it, just like the auto-sear mentioned above.

Safeties are hopeless. If you have an M16 safety in your rifle, disassemble the lower, remove the safety, and install a proper AR-15 safety. There is no practical way to un-M16 the safety.

Here we have a real mess. Some of the state laws are so irrational, so off-the-wall, that they make the feds seem civil, rational and polite. For example, in Ohio, any magazine over thirty rounds capacity is a machine gun. So, driving to Indiana with your legal, travel-form-approved SBR, you’re fine. You’re covered. But the extended magazine you’ll use in the match is a machine gun under Ohio law, and could get you in trouble. Yes, you read that correctly. The magazine, in and of itself, is a machine gun, not merely a machine gun part, in Ohio.

California is so easy, it is almost embarrassing picking on them, but here we go. Threaded muzzles. You can’t have them, they make it too easy to attach a suppressor. And you can’t just silver-solder or otherwise attached a cover, as the threads are still there. Oh, and no flash hiders, either. Magazines that are allowed only if they need a tool to remove them, thus the “bullet button” magazine catch for California rifles.

A barrel extension has to be permanently attached to count for length. Screwing on a suppressor doesn’t count, and doesn’t make an SBR long enough.

Traveling through, moving to, or simply visiting such states, you do not get any leeway because you don’t live there.

Here we have the burst-fire trigger and disconnectors. Yes, plural disconnectors, and a stupid design, too.

So, if you are to own an AR-15, you have to know the laws of your jurisdiction and those where you will be taking it for a visit. The feds won’t trump state laws, and you must know them.

In this day and age it is easy to go to the web page of your state, the Attorney General or the state police and read the laws. Your local gun shop probably has a good idea of the broad strokes of the law, but they might be a bit fuzzy on some of the particulars. Read up, frequent internet forums and also have the Rifle and Pistol Association (or whatever it is called) of your state in your bookmarks. Be sure you know the particulars and peculiarities in your area. You never know, what you think is the perfect arrangement of parts to create the best AR ever, might just be a technical violation of the law. And when it comes to guns, the authorities in many places are just as happy to hammer down on technicalities as they are real criminals.

This isn’t an M16 trigger, it has been modified by Colt to fit an AR that has a steel block in the lower.

No-one has touched this with a cutting tool of any kind, and someone-somewhere would be willing to prosecute you for owning it. Know your state laws.

This is a zero-percent lower receiver. It has had no machining work done to it at all. I’ll bet there is some state where it is a “firearm.”

What is this eighty-percent receiver you speak of? Simple. The ATF, in order to get a handle on the complex process known as manufacturing, had to draw the line somewhere. Remember, there is a specific license and fee to be a manufacturer. Legislators left it to the ATF, which determined that the machining needed to create a lower receiver did not create something that could be called a “firearm” until it had passed 80% of the work needed. An “80% receiver” is one that stops short of that.

Typically, it is a receiver, in the white, that has had all the work done except carving out the recess for the hammer, trigger and such, and drilling the holes for their pins (and the safety/selector). A receiver at this point is still a lump of aluminum as far as the ATF is concerned. (State laws may vary.) Once you start the drilling/milling, etc., it becomes a firearm.

Some shooters, perhaps not as clever as they think they are, buy 80% receivers and finish the work themselves. As long as they do all the work themselves, and do not do it for profit or to deliver to someone else, all is kosher. But the process is fraught with pitfalls.

You have to do the work yourself. That means you can’t hand it to your buddy the machinist with blueprints and come back in an hour, day, whatever. In that case, he does the work, he delivers it to you, he’s a manufacturer, and you have taken possession of a firearm from a manufacturer, sans form 4473. You’ve both just committed federal felonies.

The desire to avoid “paperwork” typically drives this. One problem: soft aluminum won’t stand up to use. So, you have to have it anodized. Guess what? Anyone who anodizes firearms has an FFL and will enter your lower in their records. No FFL? We’re back to committing federal felonies for anodizing. That said, some receivers can be had anodized, but you still leave soft aluminum any place you drill or machine. Not as useful as you might think.

Most rifles you’ll see will come with an AR-15 hammer, with the firing pin catch notch on it.

This trigger is from a burst-fire parts set. You can’t even get it to work with a normal disconnector, and you gain nothing but risk by owning it.

Another aspect of the manufacturing process comes into play. The ATF has had an acrimonious relationship at times with the general group of people who are custom gunsmiths. The ATF has tried to get such simple tasks as re-barreling a rifle, or re-stocking, declared “manufacturing.” One aspect they are clear about is that a gunsmith cannot order up a slew of parts, assemble firearms, and then sell them at retail, without a manufacturers license. Well, they can, but no more than 50 a year.

So, you cannot go to your local gun shop, one with a gunsmith in the back, and order up a lower, its internal parts, and then ask, “Say, can you guys put this together for me?’ That makes them a manufacturer. Not that people don’t do it, but if the ATF gets wind of it, oh boy.

What you have to do, to protect both you and the gunsmith, is make a good-faith effort to assemble it yourself. Then, if you fail, take the partially-assembled, inadequately-functioning rifle to the gunsmith, and ask him to fix it for you.

A lot of people are quite lax about things like this, especially since the ATF regs are often unclear. But the basics are clear: you can buy lowers (through an FFL, on a 4473) and assemble them into rifles for yourself. What you can’t do is make a business, or even a hobby, of buying stripped lowers, assembling them, and then selling them, lacking a manufacturers license.

The question of “build parties” comes up from time to time. You and a bunch of friends can get together and help each other, working through the process of building a lower, uppers, or complete rifles from parts. But you can’t do it at a licensed location, because that would mean the FFL is facilitating manufacturing.

No one can charge for anything used in the build party. Not electricity or hourly time in the shop, not rental on tools, not replacement of broken parts, nothing. I’d even be leery of letting whoever’s shop (or garage) it is get free pizza when the group orders. I’ve been accused of being overly cautious on such things, but, bottom line, the law says you can’t manufacture without a manufacturers license. I’m not going to do anything that even looks like I’m doing that, or saying that you should do it.