Two

“A lie’s a lie, even when it’s wearing Sunday clothes. That doesn’t mean a lie is necessarily the wrong choice. Just that you shouldn’t pretend it’s something that it’s not.”

—Alice Healy

Heading for the customer service desk of a major airline

THE THREE WOMEN BEHIND the customer service desk were all doing their best to look alert, engaged, and available, all while paying absolutely no attention to the throngs of people passing by in front of them. If they made eye contact, they risked triggering a complaint, or sometimes worse, a long, involved story from a weary traveler who was just looking for a moment of human connection. Great in its place, not so much fun for the person who was bound by professional obligations to sit and listen to every little twist and turn.

Their distraction was a gift for me. I stopped a few feet away, patting my pockets and allowing an expression of bewildered distress to grow on my face. I can’t read most human expressions, but I can mimic them: telepathy means that I know what they feel like from the inside.

While I was going through my acceptable airport behavior pantomime, I dipped as far as I dared into each of their minds, checking to see who felt the most pliable, and who was thus the most likely to do what I wanted without either making a fuss or declaring me their long-lost sister. The TSA man with the eighty dollars had been more than enough found family for one day.

The one on the end. She was the youngest, the least experienced, and most importantly, the most offended by the inequalities she saw on a daily basis. I stopped patting my pockets and approached her station, putting a waver into my voice as I asked, “Excuse me? Is this where I go if I need help?”

Her head snapped up and her posture shifted to one of helpful attentiveness. If I hadn’t known better, I would never have known she’d been reading fanfic on her phone half a second previously. “How can I help you today?”

“I can’t find my boarding pass,” I said. “Please, can you help me?” I let my thoughts push forward, just a little. Not enough to qualify as a full compulsion, but enough to make it clear what I wanted to have happen. You know me, I thought. You don’t need to ask for ID.

“Really, Bridget, again?” she asked, fond exasperation in her tone, and began typing rapidly. “This needs to stop happening, honey. You need to buy yourself a purse or something.”

“I guess I do,” I said, feeling suddenly uneasy. It’s not common for people to come up with their own names for me. It’s not unheard of, but . . .

It usually means those people have come into contact with another cuckoo, someone who’s already taken the time to push and pull and reshape their neurological pathways into something easier for telepathy to work with. I could be in another cuckoo’s hunting grounds right now. It’s not an unreasonable idea. As I said before, airports are liminal spaces. People come and go and if they sometimes seem to forget things or act in unusual ways, as long as those changes don’t make them appear dangerous to a casual onlooker, no one’s going to notice.

No. I’d know if there were another cuckoo this close to home. There’s a sort of feedback that happens when we get too close to each other, a telepathic static that washes over everything and makes it jittery and strange. Mom doesn’t notice it, since she’s not a receptive telepath, but I do, and the silence when I walk away from her is sometimes the loudest thing in the world. That roaring silence was still there. I could hear it. There was no one else.

The woman behind the desk was waiting, hands raised, radiating expectation. I missed something. I’d been looking for cuckoos, and I missed something.

Damn, I thought, and said sheepishly, “I’m sorry. You know I don’t mean to.”

“I know,” said the woman, relaxing slightly. The other two customer service employees didn’t appear to have noticed me, which only reinforced the idea that another cuckoo had come to visit, probably more than once. They didn’t see me because they didn’t care, because I wasn’t unusual. They’d seen me before, or someone who looked so much like me that they couldn’t tell the difference.

Humans have an incredible diversity of appearances. Different face shapes, eye shapes, eye colors, all sorts of little variations that people consider more or less appealing. It’s part of the way mammalian life in this dimension works. Everything looks different from everything else. Cuckoos . . . don’t. We come from another evolutionary path, and like most insects, we’re all virtually identical to one another. My face is my adoptive mother’s face is my biological mother’s face, all the way back to the beginning. We don’t vary, except in age and personal grooming choices. We are, in many ways, a hive.

Cuckoos are pale. Cuckoos are black-haired and blue-eyed and delicate, with features some humans see as “doll-like,” and some see as “creepy.” The humans who find us unnerving are the lucky ones. They might walk the other way when they see us coming. They might get away. Not usually, though. We can pick up on feelings of unease, and too many of my relatives view those people as a challenge, something to be pursued and overcome.

The woman started to type. “Where are you heading today?”

“Portland. The one in Oregon, not the one in Maine.”

“That’s good—we don’t have any flights left to Maine today.” She frowned at something on her screen. “That’s odd. I don’t have you listed on the manifest. Are you flying stand-by again?”

Bridget, whoever she is, must be connected to the airline somehow. “I am,” I ventured.

“That explains it. These systems need an upgrade in the worst way.” She resumed typing, faster now, plugging in the details of my supposed ID without once asking to verify it. “All right, honey, I’ve got you back on the correct plane—and since first class didn’t check in full, I’ve managed to upgrade you a couple of levels.” Her printer spat out a boarding pass. She handed it to me, eyes twinkling, radiating satisfaction at having done a favor for a friend. “Now don’t lose this one, all right? I can only save your bacon so many times.”

“I won’t, I promise,” I said, taking the boarding pass and holding it close to my chest, like it was the most precious thing in the world—which, in many ways, it was. It was one more piece of proof that I was recovered enough to leave the safety of Ohio. All I needed to do after this was get on the plane and make it to Oregon without accidentally diverting us to Prague, and I’d be free.

The woman’s eyes widened. A moment later, she was offering me a tissue. “Honey, your nose is running.”

My nose . . . oh, no. I took the tissue with a mumbled, “Thank you,” and took off, not saying goodbye. Let the woman assume I was booking it for the bathroom because I was embarrassed to have been caught with a runny nose in public.

Human blood is red. Human nosebleeds are obvious.

Cuckoo blood is almost clear, made up of hemolymph and plasma. It looks, to human eyes, like slightly blue-tinged mucus. When set against something as pale as my skin, the blue blends into the background, and a nosebleed looks more like I need a good decongestant.

I waited until I was far enough from the desk to not be observed by anyone who might know “Bridget” before I ducked into the alcove next to a pair of vending machines and wiped my upper lip. A trace of blue shimmered on the tissue. I was bleeding. Damn. Damn, damn, damn.

I needed to call home. I needed to tell Mom I couldn’t do this yet and ask her to come get me. I needed—

I lowered my other hand and looked at the boarding pass I was still clutching. One first class ticket to Portland, Oregon, leaving in under an hour. They’d be boarding soon.

One tissue, lightly streaked with blue.

I had two choices, and I couldn’t make them both. Go home and keep hiding and hoping that one day I’d be exactly the girl I’d been before I hurt myself or get on that plane and go to where people who loved me were waiting for some sign that I was truly going to recover. Go where Artie was waiting. I hadn’t seen him in five years. I hadn’t touched his hand in five years. Would the telepathic channel we’d opened between ourselves even work anymore? I’d never gone that long without reinforcing it. Maybe we’d be strangers again.

Go home or keep going. I couldn’t have it both ways.

I closed my eyes, taking a deep breath, before I crumpled the tissue and shoved it into my pocket. I had a plane to catch.

First class is nice. For one thing, there’s never any fighting over the overhead bins. For another, the seats are large enough that there’s no chance of accidental contact with the person next to you. I curled my legs underneath me, stockinged feet pressed against the hard side of the armrest—designed to maximize my personal space as much as possible, thank you, human veneration of the wealthy—and sipped my tomato juice as I stared out the window at the receding shape of Cleveland, Ohio.

Back in Dublin, my parents were probably watching the airport departures list, waiting for the last plane to Portland to take off. If I didn’t call them a half hour after that, they’d know I was on my way, finally taking my first real step toward rejoining the world. Mom wouldn’t sleep until I landed in Oregon and texted her to let her know I was all right. That was fine. She usually had some snarly accounting problem to keep her distracted. Or maybe she and Dad would take advantage of having the house to themselves for five minutes. Alex and Shelby were in Australia, Drew was in California, and I was on a plane. They could—

Ew. No. I didn’t want to think about that. We’re all adults, but there are some thoughts that send me hurtling right back into easily horrified childhood.

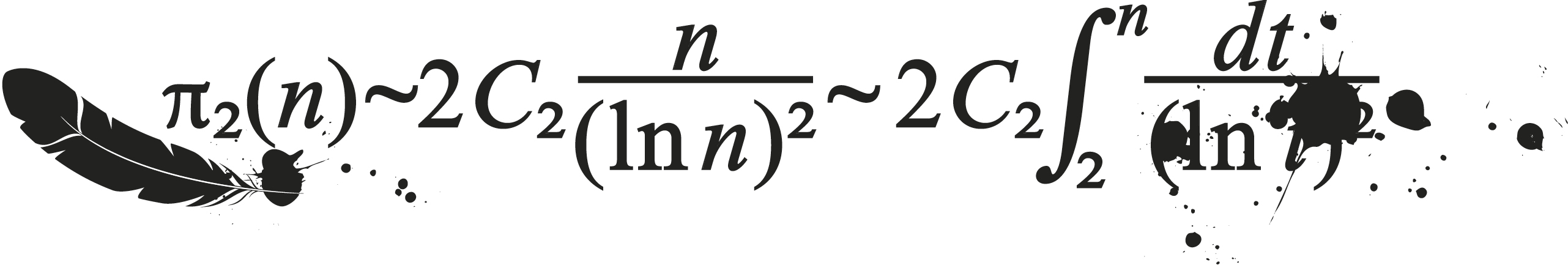

The man who was sitting next to me had been trying to get my attention since takeoff. The fact that I was wearing headphones and staring fixedly out the window didn’t appear to be doing anything to dissuade him. If anything, it was just making him try harder. I did my resolute best to ignore the increasing waves of irritation and impatience rolling off him, focusing instead on my recording of the latest lecture series from the American Mathematical Association. They were doing some fascinating things with intuitive primes, and I wanted to see how far they could take the theory before things either resolved or fell apart.

In math, something is either true or it’s not. Something either works or it doesn’t. If something works and it feels like that shouldn’t be possible, it’s not the math that’s wrong: it’s your model of the universe. Mathematics is the art of refining our understanding of reality itself, like a sculptor trimming down a brick of marble until it frees the beautiful image inside.

Math is also distracting for me, like it is for any cuckoo. Something about the calm march of numbers and theory and equations is utterly enthralling to us. We’re an entire species of mathematicians, and that fact is the only thing that keeps me believing we can’t be all bad. How can anyone who truly loves numbers be irredeemable?

I was so wrapped up in the equations that I didn’t realize the man was planning to move until he hooked a finger around the cord of my right headphone and popped it out of my ear. The drone of the plane’s engine came roaring back, drowning out the lecture still playing in my left ear, followed by the sound of his smug, faintly nasal voice.

“I said, will you let me buy you a drink? Pretty lady like you shouldn’t have to fly alone.” He laughed, amused by his own feeble attempt at humor. “Of course, this is first class, so the drinks are free . . . unless you want to go someplace nicer with me after we land. I could show you a good time.”

Of course. Of course. There are days when I wish whatever evolutionary path had decided I should pass for human could have settled on something a little less eye-catching. Not that being pretty by human standards doesn’t smooth a lot of rough edges out for me, but it can create a few, too.

I turned to face him, offering a thin, glossy smile. “No, thank you,” I said. “I’m sorry. I just want to listen to my book and get some rest.” I could have tried to shove “you’re not interested in me” at him, but at our current proximity, that was likely to result in him deciding I didn’t exist and trying to claim my armrest.

“Book?” He grabbed the headphone before I could protest, bringing it to his own ear. A wave of confusion and disgust rolled off him an instant later. “This isn’t a book. This is a lecture.”

“It’s a lecture taken from a book on mathematics.” I tweaked the cord nimbly out of his fingers, pulling it protectively closer to myself. “I don’t want any trouble.”

“I think you need a little trouble,” he said, and grabbed my wrist.

Big mistake.

Maybe once, I could have kept myself pulled back enough not to touch his mind even while he was touching my body. Maybe. But that was before my injury, and before I’d been forced to relearn the little tricks and techniques that made it safe for me to move through the human world. My agitation boiled over, and I saw the flash of white reflected in his eyes before he let go of me, withdrawing into his own seat.

“I’m so sorry,” he said. His tone had completely changed, becoming contrite, even guilty. “That was entirely inappropriate of me. I can’t believe . . . I’m so sorry. I’ll make this right.”

He hit his flight attendant call button. I put my headphone back in and returned my attention to the window, trying to radiate “I’m not involved with this” while I watched the clouds and he spoke in a low, urgent voice to the flight attendant who answered his call. I could feel his self-recrimination prickling against my skin like steel wool, but if I didn’t reach for details, I wouldn’t find them, and that suited me just fine. Not everything can be my problem. There isn’t room in my head.

There was a flurry of motion as the man got up and moved away. A few moments later, the flight attendant was waving her hand for my attention. I straightened, removing both headphones, and turned to face her.

There was a woman behind her in the aisle, no more than twenty-five years old, with a baby grasped against her chest and a massive diaper bag in her free hand. The woman was looking around, radiating awe. The baby was sleeping. All I got from it was a pure, unalloyed contentment. It was with its mother, it was fed and safe and content, and it wanted for nothing else in the world.

Lucky baby. “Yes?” I asked.

“The gentleman who was seated next to you has requested a transfer to coach class, and that we credit the value of his ticket to another passenger who looks as if they’d enjoy the opportunity to experience our first-class cabin.” Her eyes gleamed. I picked up a combination of genuine joy and malicious anticipation, aimed not at me in specific, but at the rest of the cabin.

Apparently, my former traveling companion wasn’t the only one who’d felt entitled to be a little too pushy about his own desires. I couldn’t get details without digging deeper, but I felt fairly confident that the woman behind the flight attendant had been chosen at least partially to annoy the rest of first class as much as possible.

Well, that was fine. I smiled broadly, and said, “That sounds great. One of my cousins is expecting a baby soon, so I should probably be spending more time around infants anyway. Getting in practice, right?”

The flight attendant’s smile was mostly relief, and only a sliver of disappointment, as she waved the woman to her seat and tucked the diaper bag into the overhead compartment. In only a few seconds, we were alone—or as alone as you can ever get on a plane—the woman radiating wonder, the baby still comfortably asleep.

I smiled at her, dazzlingly bright, an expression I learned from sliding myself into my cousin Verity’s head during her dance competitions. Verity learned to smile like she was being graded on it, because she was, and thanks to her, I share the skill. Not bad for someone who can’t always recognize a smile when she sees one.

“I’m Sarah,” I said. “First time in first class?”

“Yes,” said the woman. “I . . . yes. I’m Christina. This is Susie.” She gave the baby a little bounce, not enough to wake it up.

She was thinking “my little girl” so loudly that I could actually hear the words, so I turned my smile on the baby and said, “She’s beautiful. Let me know if you need me to hold her so you can use the bathroom.”

Her astonishment was, briefly, louder than the plane’s engines. I gave her another smile and returned my attention to the window. We were on our way to Portland, and I didn’t have a jerk sitting next to me anymore.

Things were looking up.

The plane touched down with a thump hard enough to set us all rocking for a moment, stirring the infant next to me back into fussy wakefulness. I smiled encouragingly at her mother, offering a little wiggle of my fingers as distraction. The mother radiated relief. Apparently, flying with an infant was a horror—I could have guessed that—and people were frequently resistant to the idea of flying next to one—I had observed that. Being moved up from coach to first class and seated next to someone who didn’t mind babies had been like winning the lottery on multiple axes at once.

I like babies. They’re simple. Their thoughts are simple, their needs and desires are simple, and if I need something soothing, I can watch their synapses making lasting connections, a process most adults have long since finished. Plus, babies have such basic inner lives that I don’t really feel like I’m eavesdropping when I listen in on them. This baby had such a limited set of experiences that she didn’t yet know her name, or have preferred pronouns, or really understand that her toes were always there, even when she was wearing shoes. She was like a tiny, occasionally smelly meditation trigger.

“It was nice to meet you,” said Christina. “Is someone picking you up from the airport?”

She wasn’t angling for a ride, I realized; she was preparing to offer me one. Oh, that wasn’t good. If we got into a private car, after the amount of time we’d spent together, I’d be a member of her family before we could get on the freeway. She was too nice to spend the rest of her life feeling wistfully like she’d somehow misplaced her favorite sister.

“I’m good,” I said. “This was sort of a spontaneous trip, and I have family here. I’ll be fine. But thank you for asking.”

Both statements were true, even if neither of them answered her question. I was planning to head down to the taxi stand and invite myself along on a ride that was heading toward the family compound. It would be safer, since whoever actually paid for the cab wouldn’t have been sitting next to me for the last several hours.

“No problem at all,” said Christina. Susie fussed. Christina turned her attention to the baby.

That was my cue. Fishing my phone out of my jeans pocket, I turned it back on, and winced as it began buzzing frantically in my hand. Almost thirty text messages had come through while it was shut down for the flight, which seemed a tiny bit excessive.

The first ten were from Mom, wanting to let me know that she was thinking about me, she was worrying about me, she was pretty sure I was on the plane by now, but if I wasn’t, I could come home and she wouldn’t be angry, it was okay if I needed more time. The next five were also from Mom, and were a little closer to flipping out—in one of them, she suggested I make it a round trip, get off the plane in Portland, and get immediately back onto a flight heading for Cleveland. Ugh. No thank you. I’d had my fill of being crammed into a flying metal tube of human minds and human fears, and I wanted to rest.

After that came a series of texts from Dad, detailing the steps he was taking to try and calm Mom down, and reminding me how important it was that I text her as soon as we landed if I didn’t want her to come to Oregon and shake me vigorously back and forth. I smiled at that, and switched back to Mom’s messages, intending to do as he’d suggested. It was better not to put this off.

Then my phone buzzed again, and I nearly dropped it. Artie. I had a text from Artie.

Trying to be nonchalant, I finished my text to Mom—“Safe on the ground. Made it to Portland. No headache. Think I’m okay.”—before taking a deep breath and opening my latest message.

Just had weirdest feeling, it read. Like you were almost in the room. Miss you.

For the second time in under a minute, I nearly dropped my phone.

Wow, I replied. Weird. Where r u?

Text grammar makes my teeth ache a little. When I was in school, part of my job was learning to blend into the human population. Don’t stand out, don’t make waves, don’t attract attention. Do what everybody else does, because the wisdom of the herd is the best possible camouflage. That’s spilled over into my adult life, meaning, among other things, that I have to text like I don’t care if anyone’s judging my spelling.

I care. I care a lot. But we do what we have to do to survive in this world.

Home, Artie replied. Face-chat tonight? We can watch a movie.

Can’t. Will explain soon. I added several emoji—two snakes, a smiling girl, a rainbow, a bee—and shoved the phone back into my pocket before I could see any reply. I wasn’t there yet. I needed to make it all the way to a safe house if I wanted to pass the test Mom had set for me.

The plane finished taxiing to the gate, and the flight attendants turned off the fasten seatbelt sign. I bounced out of my seat, sliding past Christina and the once-again sleeping Susie, and grabbed my backpack out of the overhead compartment, slipping my arms through the straps before the cabin door was even open. It unsealed with a hiss and I was out, not running, but walking very quickly away from the rest of the passengers.

I knew too much about them. I didn’t know what they looked like, and it didn’t matter, because I knew what they thought like. I knew who was cruel and who was kind and who probably needed to be hit with a baseball bat for the things they believed were okay to do to their fellow humans. I was just glad the entire plane had been human. Being stuck with too many kinds of minds would have been even worse.

I strode my way along the jet bridge to the terminal, sucking in great breaths of fresh airport air, which might be processed, but hadn’t been circulated through the cabin for the last several hours. I wanted a bathroom and a salad and a ride home. I wanted—

I stepped into the terminal and stopped dead in my tracks, suddenly feeling like I’d been punched in the gut. People streamed out behind me, shooting sour thoughts about people who stopped in walkways in my direction. I didn’t move. I was struggling to breathe. The thoughts stopped, replaced by weary irritation at the need to step around some inanimate but unavoidable obstacle. I was cloaking myself. I wasn’t trying to, but I was, and I couldn’t stop, because I couldn’t breathe. I couldn’t move.

The static roar was drowning out everything else, filling my mind from end to end, so that even the thoughts of the people behind me were muffled, becoming little more than background noise. They were inconsequential in the face of something so much bigger.

There was another cuckoo in the airport.