Eleven

“Never go anywhere unprepared, unarmed, or unaccompanied. The difference between success and suicide is often a matter of prior planning.”

—Evelyn Baker

Getting ready to leave the living room, wondering if stupid things are any less stupid when you know that they’re a really bad idea

MY MIND WHIRLED AS I tried to think through the implications of the email. It was a threat, absolutely: someone who just wanted to sell me Girl Scout cookies wouldn’t have told me not to ask for help. I didn’t know how a stranger could have made it past the gate, but there are always ways, for someone determined enough.

They’d told me not to call for help, not even telepathically. I’d been careful, though; there was no way my system had picked up a virus from the email, not with all the firewalls and barriers I had in place. I could send Annie an email, and—

A chat window appeared at the bottom of my email client. Don’t even think about it.

My gut twisted. Who are you?

The person you’re about to come outside to see. Don’t try to send an email, Sarah. I’ll know. Get up and walk away. Don’t make a fuss. Do it now. Or else.

Or else what?

Or else there will be consequences.

If I’d had a heart, that last word would have been enough to make it seize in my chest. “Consequences.” That wasn’t the word of someone who was playing around or making idle threats. That was the word of someone who was willing to do serious damage to get what they wanted.

My parents raised me to know my own worth and value myself as an individual. But nothing—nothing—would make me more important than the rest of my family. I couldn’t let it. Part of what separates me from the other cuckoos is knowing, really knowing, that other people matter. An ordinary cuckoo couldn’t be lured outside by a word like “consequences.” I . . .

I had to go.

Carefully, I stood, leaving my computer where it was. Annie would know something was wrong when she came down and saw it sitting there unattended. I don’t like other people using my things. I never leave them out in the open if I have any other choice. She’d notice. She had to notice. Someone would notice.

Someone would notice I was gone.

I walked slowly toward the kitchen, and through it to the front door. The temperature outside had dropped even further, becoming just shy of freezing. I could feel it, but it didn’t affect me the way it did the true mammals. Wherever we came from, it was a much colder place.

I paused when I reached the edge of the porch, mentally reaching out into the yard, looking for any mind that didn’t belong there. I found him near the fence, a silent, unremarkable presence that had somehow managed to go unnoticed until I started looking. This was bad. This was very, very bad. Awareness of his presence came with awareness of the static that had been growing in the back of my mind, lighter and more subtle than I expected it to be, a fizzing, bubbling proof of presence.

I resumed walking. Every step took me closer to that unknown mind. It came further and further into clarity, resolving from a presence to a person to a cuckoo. There’s a certain sharpness to a cuckoo’s thoughts, like biting into a strawberry and suddenly discovering that it’s actually a lime. They tingle and fizz and even burn.

These thoughts didn’t quite burn. They were sharp, yes, curling in on themselves like the fronds of a fern, protecting themselves from being read. I could see their superficial lines. Nothing more. They were too deeply rooted in the man they belonged to, and they didn’t want to let their secrets out.

I walked silently toward him, wishing my inhuman capabilities had come with some good, old-fashioned night vision. Part of the question was answered when I reached the fence: the man who’d emailed me wasn’t inside the boundaries. He hadn’t managed to get past the gate. Instead, he was standing at the very edge of the trees, a pale blur in the darkness, lit by the glow from his cellphone screen. He glanced up, raised one finger to signal me to silence, and returned his attention to the phone, finishing whatever message he’d been preparing to send.

“You know, it’s rude to demand someone come outside and then ignore them,” I said.

Don’t speak. His words were clumsy, distorted, like he was pushing them through a wall of water. They might hear you if you speak.

Who are you? I demanded.

His head snapped up, eyes glowing white. I resisted the urge to take a step back. I’d known he was a cuckoo, known he had to be a cuckoo, but knowing and seeing are different things.

Like the female of our species, male cuckoos all look essentially alike, pale-skinned, dark-haired, blue-eyed. We were designed by the same evolutionary forces, intended to survive the same environment. To someone whose brain was designed to process the information, his face would look enough like mine that he could have been my brother, and dissimilar enough that if we’d held hands and walked down the center of a mall together, no one would have looked twice. Oh, the ones who looked once might think we were a little narcissistic for dating someone so similar, but they wouldn’t jump straight to a bad conclusion.

Two cuckoos in the same place is a bad conclusion, almost always.

He was wearing jeans and a dark sweater, helping him blend into the trees. Amusement colored his distorted tone as he replied, You can call me Mark. You want to come over here and hold my hand? This would be easier if you were touching me.

I’m not touching you. The thought was revolting. How are you here?

You really don’t know anything, do you? It’s amazing. It’s like finding a diamond in the middle of a chum bucket. You have to wipe off all the gore before it can shine.

I narrowed my eyes. A faint wind rose around me, fluttering my hair. I know enough to know I want you gone.

Mark made a small scoffing sound. It was the first audible noise he’d made since my arrival. It’s cliché, I know, but make me.

I couldn’t. He knew it, and I knew it, and so we were at an impasse. Or maybe not. “I don’t have to make you,” I said aloud, enjoying the way he tensed at the sound of my voice. “All I have to do is call my family.”

“Funny,” he said, his own voice pitched low and tight to keep it from carrying across the grounds. “I was under the impression that you cared about them.”

That gave me pause. Narrowing my eyes further, I shot a sharp thought at him. You touch them and you die.

“Oh, now you’ll talk to me like a civilized person? You’ve been living among the humans for too long, Sarah. What went wrong inside that pretty little head of yours? You should have entered your second instar when you reached puberty, and you didn’t. You held it off for years, and look at you now. Frightened. Pathetic. Moral.” He sounded genuinely disgusted by the last word, practically spitting it at my feet. “How did you delay your metamorphosis?”

“What’s an instar?”

His eyes widened. “This is worse than I thought. Why in the—it doesn’t matter. It isn’t my problem, I’m just the retrieval guy. Here’s what you’re going to do. You’re going to walk to the gate, and you’re going to let yourself out. You’re going to come with me. No alarms, no attracting attention to yourself, no funny business. And then we’re going to leave.”

“Why the hell would I do that?”

“Because if you don’t, then you’d better be prepared for a siege.” He leaned forward. “The blood of Kairos isn’t enough to protect these people from us. We’ll hem them in, pin them down, and have them, one by one—and that’s just the ones within these walls. We know where the Lilu live. Their defenses aren’t as good as they ought to be. They’ll be dead by morning, all of them, and it will be your fault, Sarah. You’ll finally have done what a good little second-instar cuckoo ought to do and killed the family that raised you. Is that what you want?”

He wasn’t making any effort to shield his thoughts or emotions from me. Calm conviction radiated around him, colored with the absolute serenity of truth. He wasn’t lying. He wasn’t trying to deceive. He genuinely believed every word he was saying.

“You can’t . . .” I began. Words failed me, so I continued in silence, You can’t. They’re Prices. They’ve beaten cuckoos before. They’ve beaten everything.

“Three of them are Prices,” said Mark. “Two of them married in. The Lilu and the one who thinks of herself as your sister—and that’s disgusting, by the way, do you always let your pets have that much power over you? It’s vile. They’re not Prices, not genetically. The boys aren’t Prices either. The fūri might be a problem. He could probably hurt a few of us before we shut him down. The sorcerer is less than half-trained, and he wants. He wants so badly that we know everything we need to know. We can break him. We can break them all. It’s your choice, Sarah. Come quietly, come now, and we leave them alone. Sound the alarm, fight us, and we take them down before we take you anyway. The end result is the same.”

He was utterly sincere. I couldn’t see his thoughts well enough to know how many cuckoos he had with him, but I got the impression of at least five—a larger swarm than anyone had ever documented. Cuckoos usually work together only at mating time, and then only for as long as it takes the child to be conceived, carried, delivered, and deposited with an unwitting host family. Six cuckoos in one place wasn’t just dangerous: it was a natural disaster.

“Seven,” he said.

I snapped my head up, staring at him. “You’re starting a countdown now? Don’t those usually begin with ‘ten’?”

“Not a countdown,” he said. “A clarification. There are seven of us. You’re a cuckoo, too.”

The cuckoo choice would be to go back inside and sound the alarm. I would be safe. I would be protected. I would be selfish. I’d be putting my entire family at risk. I looked at the other cuckoo, who looked politely back. He somehow managed to look like he was focusing on my face, the lines and angles of it, as if he could actually see it like a human would. It was a good trick.

I took a slow breath. My whole body ached with the stress of the moment, and with the knowledge of what I was about to do.

“If I come with you, you stay the hell away from them,” I said. “You don’t come back and start making trouble as soon as my back is turned.”

Amusement radiated through his thoughts, warm as morning sunlight. “How are you going to hold me to that?”

“I don’t know. But I am. If you ever come anywhere near here again, I will kill you. Maybe only you. Maybe the rest of the cuckoos get away. Maybe you kill me in the process. Doesn’t matter. It means there’s one less cuckoo on your side, and that shifts the numbers in a way that I can live with.”

“Two less,” he said.

I frowned. “What?”

“You said there would be one less cuckoo on my side. There would be two less. I would kill you, princess. It might be the last thing I ever did, but I’d do it.”

“I’m not on your side.”

“You will be.” He cocked his head, like he was listening. I didn’t hear anything. He was the only cuckoo close enough for me to detect. He must have been playing relay with someone who was in his range but not in mine.

That didn’t necessarily mean he was stronger than me. There are plenty of things a cuckoo can do—plenty of things I knew how to do—to increase their range where a specific person was concerned. Maybe he’d been willing to stay in contact with another cuckoo long enough to become attuned to them. It was strange. A whole pack of cuckoos coming for me was even stranger.

“Fine,” he said finally, eyes flashing white. “We give you our word that no one will come back here to interfere with your family. We can’t promise they’ll be spared if they track us down. Take it or leave it, because we’ve already been out here too long.”

They wouldn’t thank me for this. Family is supposed to be the most important thing in our world, and by walking away, I was as good as saying that my family couldn’t protect me. The thing was, they couldn’t protect me. Not against this. Not against an enemy that could get inside their heads. Anti-telepathy charms are the solution against one cuckoo, acting alone or trying to defend their territory. They wouldn’t hold the line against a group of them. They would just make the enemy harder to see coming.

My family had protected me after New York. It was my turn to protect them. I looked the cuckoo in the eye and nodded, once, before I turned and started for the door next to the gate.

Tucking the family compound away in the forest had been a good way to control traffic in and out. It hadn’t eliminated the need for things like getting the hell away from your family, hence the occasional doors set into the fence. Without them, my cousins—Verity especially—would have been forever setting off the motion detectors along the top as they climbed their way to freedom. Sure, freedom looked like an evergreen forest in the middle of nowhere, but it was still freedom.

Or it had been. I keyed in the gate code, which I’d lifted from Kevin’s mind without even thinking about it, and stepped out of the supposed safety of the yard into the dangerous darkness of the woods. It didn’t feel like freedom anymore. It felt like walking into a trap.

The cuckoo nodded approvingly. “Come with me,” he said, then turned and led me deeper into the trees.

Lacking any real choice, I followed.

We walked until the compound lights dwindled to nothing behind us. Only then did Mark produce a flashlight and click it on, directing its watery beam toward the ground.

“Sorry to make you come all this way, but, well, we both know things would have gotten really ugly back there if we’d parked any closer,” he said. He sounded almost jovial, like we were old friends going for a walk, and not virtual strangers in the middle of an abduction. “We’ll be at the RV soon.”

“An RV?” I couldn’t quite keep the disbelief out of my tone. “You brought an RV?”

“Had to,” he said. “We don’t squish well, not even when we have a good reason to be working together. It’s a really nice one, too. Modern. There’s even a bathroom it’s not physically painful to use. Amelia and David took a few recreational trips back there while the bedroom was occupied. He’s pretty mad at you, by the way.”

“For what?” I asked. “All I did was hit her with my backpack.”

“I didn’t say it was logical, just that it was there,” said Mark. “Amelia saw you first. That meant she got the duty and the honor of triggering your next metamorphosis. Unfortunately, she couldn’t exactly survive something like that. She died like she lived. Pissed off at the entire world and willing to do whatever she could to destroy it. Honestly, I think David’s mostly angry because he knows that if their positions had been reversed, Amelia would be perfectly happy to have him gone, if it meant you were progressing to your next instar.”

I stopped walking. Mark continued for a few more feet before turning to look at me, projecting polite confusion.

“We’re not there yet,” he said. “Like I said, we have to keep walking.”

“You keep using this word, ‘instar,’” I said. “What the hell does it mean?”

“Can’t you take the definition from me?” he asked. “You should be able to reach out and snatch it from my mind. If you can’t, that’s not my problem.”

“That’s not how I do things,” I said.

“That’s not how humans do things,” he said. “You, though, Sarah Zellaby? That’s exactly how you do things. You act like you have some moral high ground because you only hunt people you’ve decided somehow deserve it, but you’re just like the rest of us. You take. You take, and you take, and you take, and you don’t give anything back. You can’t help yourself. If you could, you’d be useless to us. You want to know what an instar is? Take it.”

I stared at him, feeling my eyes burn as they went white. How dare he talk to me like that, like I was doing something wrong by trying to be careful. Even more, how dare he remind me of what I already knew and wanted to forget about. There were no questions left in my mind, only anger, and the brush of the wind against my cheeks as I focused on him, trying to punch my way through his mental barriers and claim what I needed to know.

His walls were strong. Not as strong as mine, maybe, and not as strong as an anti-telepathy charm, but strong enough that I couldn’t smash through them the way I’d wanted to. I pictured my thoughts as hands, grabbing chunks out of his defenses and pulling them free. They came back as quickly as I could discard them. I made a frustrated noise.

“Okay, you can stop now.” He sounded winded. “That really hurts, you know.”

I stopped grabbing for his mind. “How can it hurt? I’m not touching you.”

“You’re not touching me where anyone can see it, but you’re definitely touching me,” he said, rubbing his temple and wincing. “Wow, you’re strong. I’ll give you this much, princess: you’re almost as impressive as I hoped you’d be. Now come on.”

“I still don’t know what an instar is.” My voice came out plaintive and tight, like a child who expected to be smacked. My gut was roiling. My whole life, I’ve tried not to hurt anyone. Now I couldn’t even bring myself to hurt another cuckoo. Instead, I was following him through the forest, so close to willingly as to make no real difference.

I paused. I was following him through the forest. No other cuckoos had appeared. If I turned and ran back to the compound now—

“Please don’t even think it,” he said wearily. “I wasn’t lying about my backup. They may not be right on top of your family’s property, but they’re close enough, and you’d never make it. This is the kindest way of doing things.”

“It doesn’t feel very kind to me,” I said.

“That’s because you’re the prize,” he said. “The prize is, well, prized. It’s desired and valued and it doesn’t get to have opinions of its own. Opinions are for soldiers and flunkies. You get to sit on a shelf and look shiny until it’s time for you to go to work.”

“What are you talking about?”

“You’ll see,” he said, and started walking again, taking our only light with him.

The woods were so dense and dark around us that I wasn’t sure I could find the compound on my own. We’d gone far enough into the trees that even the minds of the family members I was attuned to had faded into true silence—not just the static of a present but inactive connection. Maybe I’d been complicit in my own kidnapping, but at this point, I was committed.

Something rustled in the bushes behind me, something without enough of a mind for me to latch onto. I shuddered and chased after Mark and the safety of his flashlight.

“Thought so,” he said, once I drew up level with him. “Like I said, we’re almost there.”

“Why aren’t you answering my questions?” I asked.

“Prizes don’t get to ask questions,” he said.

“I’m not a prize.”

“Yeah, you are, princess. Come to terms with that sooner rather than later, if you can. This will be a lot easier for you if you do.” He stepped over a fallen log and paused to offer me his hand. “Careful. The footing’s treacherous here.”

I stared at his hand for a split second before grasping it and using it for leverage as I both stepped over the log and drove myself deep into his mind, past the layers of mental defenses, past the walls whose construction I paused long enough to both admire and study. He knew some tricks I didn’t. I wanted them. I wanted everything.

He wanted me to take? Well, he was going to get everything he wanted, and he was going to get it now.

The word “instar” was floating near the surface of his mind, almost like he’d been waiting for me to come and get it. That was silly—tell a person not to think about elephants and they won’t be able to think about anything else—but I still shrieked silent triumph as I seized hold of it and drew it into my own vocabulary.

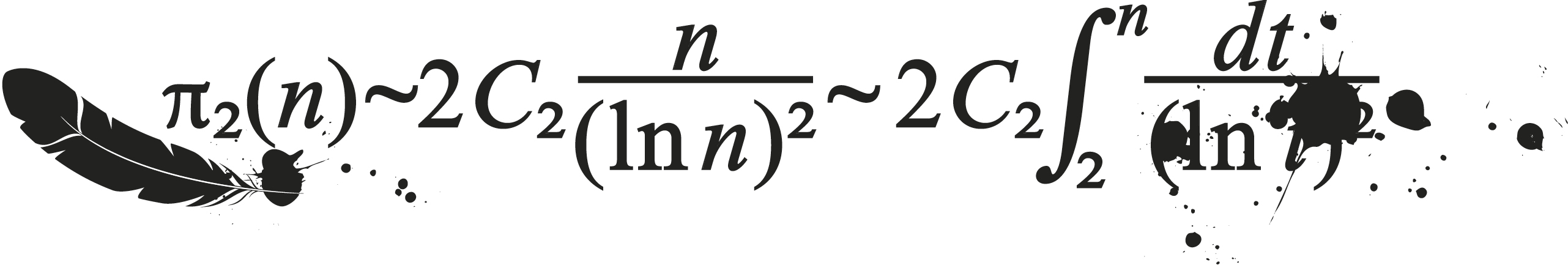

Instar: a developmental stage of insects. There was more wrapped up in the definition, science and analysis and images of butterflies bursting out of cocoons, ants breaking out of their exoskeletons, but the core of it didn’t waver, didn’t change. I dropped Mark’s hand. He staggered back, eyes wide and glinting white as he stared at me with new, slightly frightened respect.

“Skin contact,” I snarled. “Shouldn’t have given it to me.” His thoughts were clearer now. They almost formed words even without him trying to project them. “Think next time.”

“There’s not going to be a next time,” he said. “There should have never even been a first time.”

“You really want to tell me you’ve never touched anyone before in your life?”

“I’ve touched plenty of people,” he said. “I’ve never touched anyone like you.”

“Because I’ve reached my third instar,” I said.

He turned his face away.

“Don’t make me go into your thoughts again. Neither of us is going to enjoy it.” I made a motion like I was going to grab his hand. He flinched. “You don’t want that? Then talk.”

“You have no idea what you’re messing with, Sarah,” Mark said. He took a step backward, away from me, out of easy reach. That didn’t matter. Skin is easy. When all I need is skin, I can do anything. “This is so much bigger than either one of us. You need to stop.”

“You’re kidnapping me, taking through the woods to hand me over to a bunch of strangers, and taunting me with all the things I don’t know, and I’m the one who needs to stop?” I narrowed my eyes. I could see them reflected in Mark’s irises, little glints of light that meant my abilities were still on high-alert and informing everything about me. “I think you got your pronouns wrong.”

“You’ll understand soon,” he said, a note of genuine pleading in his voice. “Please. We’re almost there.”

I glared at him for a moment before I pulled myself back, taking a deep breath. We were too deep in the woods for me to make it to the compound on my own, and I needed to know why this was all happening. Whatever the fourth instar was, it was enough to frighten Mark. Maybe it would be enough to frighten the rest of them. I could resolve this without endangering the rest of my family. I could handle it. Whatever this was, I could handle it.

“All right,” I said, and let him lead me into the dark.