Twelve

“Didn’t think I’d ever have a family. Didn’t think I’d ever want one. It’s funny, how much a person can change without even noticing what’s happening.”

—Frances Brown

A logging road deep in the Oregon woods, isolated from everyone but the enemy, about to make a terrible mistake

THE RV LOOKED PERFECTLY normal, if a little swankier than most people in this neck of the woods could afford. All the lights were on, even the headlights, turning the slice of road and grassy shoulder around it buttery-yellow against the darkness of the rest of the woods. Mark huffed a sigh, radiating relief, and started walking faster. I reached for him.

“Please don’t,” he said. “I don’t want you in my head again.”

“You’re the one who kidnapped me,” I said. “I’m not sure you get to make requests.”

“I didn’t kidnap you,” he said. “I liberated you from your kidnappers.” He looked over his shoulder at me, eyes glinting momentarily white. “I know there’s a lot you don’t understand yet, but you will. You’re so close to understanding, and once you do . . . everything’s going to change, for all of us. Come on.”

He sped up again, pulling ahead of me, so that there was no possible way I could grab his hand. It was too late for me to change my mind. I followed.

The RV’s side door opened as we approached, and two more cuckoos stepped out, their minds reaching for mine in a telepath’s . . . not handshake, exactly, since that implied contact, something we were all dedicated to avoiding. It was more like a meeting between two wolves with no humans around to observe them. Our thoughts brushed by each other, taking stock, taking measure, and then moving quietly on. I caught nothing from them aside from caution and a sense of wary excitement, like they were waiting for me to do some uniquely exciting trick.

“David,” said Mark. “Heloise.”

“Out loud?” asked the one he’d called Heloise. “Like humans? Ugh. I knew the girl was provincial, but that’s disgusting.” She gave me a slow look up and down, pausing when she reached my hair. She sniffed. “Bangs. It has bangs. Mark, how dare you not tell me it had bangs. I might have chosen a different role.”

“I hadn’t seen her before she landed in Portland, any more than the rest of you had,” said Mark, sounding unruffled. “You’ll be thrilled to hear that she was hurt in the crash. There’s a cut concealed under those bangs. A nice long one.”

“How do you know that?” I asked.

“Your relatives should really wear telepathy blockers if they don’t want people to wander in and take whatever it is they want to know,” said Mark. “Honestly, if they’re the best humanity has to offer, it’s a wonder we didn’t conquer this planet centuries ago.”

“Too much work,” said David. He looked at me, eyes glinting white as a wave of malice rolled off of him like approaching thunder. “You killed Amelia.”

“I didn’t kill anyone,” I protested. I had never been around this many cuckoos in my life. The staticky hum of their presence was like white noise, making my head bubble and fizz. “I don’t know any of you people, and I still don’t know why I’m here.”

Heloise approached us, walking a circle around me as she continued her inspection. “You’re so innocent—and so domesticated. It makes me sick. We should never have allowed this to happen.”

“I don’t know you,” I repeated. “I don’t understand why you’re so worried about me.”

“You don’t seem to know much,” she said. “I’m not worried about you. I’m worried about the message it sends when we allow ourselves to be domesticated. We should have stolen you away years ago, before all this damage had been done. We could have hollowed you out ourselves. Kept you where no one would ever see. Where you wouldn’t be able to do us any damage. David? I need your phone.”

The other cuckoo pulled a phone out of his pocket and lobbed it toward Heloise. She caught it without looking and aimed it at my face, clicking several quick pictures. I blinked.

“What was that for?”

“Bangs,” she said, and tossed the phone over her shoulder. David caught it and put it back in his pocket. “I can’t cut my own hair, and I’ll need to give the stylist something to work from. Mark? Get her inside.”

“Why me?” he asked.

She looked at him, eyes glinting white as irritation sparked along the surface of her thoughts, bright and fierce and judgmental. “She’s already touched you,” she said. “The damage is done.” Turning, she stalked back to the RV. David followed.

Mark looked at me. I could feel the regret rolling off him, although I couldn’t tell whether he was sorry this had to happen, or sorry he was the one doing it to me. It didn’t matter. He wasn’t going to let me go, and he wasn’t on my side.

“I’d really rather not get close enough to grab you,” he said. “I don’t suppose you could do me a favor and come quietly? You won’t get anything else useful from me unless you rip my mind apart, and you’re not ready for that yet. I don’t want to be on your bad side once you are.”

It was tempting to lie to him, or to refuse to go along with anything he wanted from me. I was too tired to push it that way. I needed this to be over. I needed to understand what they were trying to accomplish so I could break free and go home, back to my family, back to the people who would take care of me, who I could take care of in turn.

“Fine,” I said, and flounced toward the RV.

The static white noise of the other cuckoos got stronger as I got closer. I faltered. Six cuckoos, not including myself; that was what I’d sensed from Mark back at the compound. Six cuckoos, and I was the only one who didn’t belong to their hive.

Hive. The word came easily, naturally, like it had always been the right noun for this sort of situation. It was tied to “instar,” somehow connected to the concept of insect metamorphosis, and so right that I couldn’t even try to question it. A group of cuckoos was a swarm. A group of cuckoos who had put aside their natural distaste for sharing space and territory, who had decided they could work together for some reason, was a hive. I was walking into a hive.

The RV door was unlocked. I pushed it open and stepped through, into a space like nothing I had ever seen before.

David and Heloise were in the little kitchen area, David making some sort of hot mixed drink, Heloise leaning against the counter. A massively pregnant female cuckoo reclined on the window seat, rubbing her belly in small, concentric circles, her posture radiating discomfort and suspicion. Two more cuckoos were seated toward the back, both male, both watching me enter with glowing white eyes, their suspicion hanging heavy in the air.

Mark pushed through behind me, careful not to touch me at all as he pulled the door closed behind himself. “I got her,” he said.

“We can see that,” said the pregnant cuckoo. She leveled a flat gaze on me, eyes sparking white as she reached out and brushed the fingers of her mind against my own. Her lip curled. I would have known it was disgust even if she hadn’t been broadcasting the emotion loud and clear. “This is what we’ve been waiting for? Are you sure? Have you looked at her?”

“More closely than I wanted to,” said Mark. “She took my hand for a second when I helped her over some debris—”

“Suck-up,” said one of the men. The other snickered.

“—and she had half my brain on the table in front of her before I could let go,” Mark continued, like he hadn’t heard them. “She’s a damn battering ram.”

“That’s what we need,” said the woman. She focused on me again. Her next words were silent ones, less distorted than Mark’s had been; while he’d sounded like he was talking underwater, she sounded like she was talking next to some piece of loud machinery, something that fought to steal every syllable away. You’re a fascinating experiment, Sarah Zellaby. I’d been hoping to have the chance to meet you.

“How do you know my name?” I asked.

She rolled her eyes. Have you adapted so completely to life among the humans that you’ve forgotten how to be a telepath?

“No,” I said. “Have you adapted so completely to life among the cuckoos that you’ve forgotten that it’s rude to talk telepathically in public?”

“Who told you that?” she demanded. “Your petty so-called mother, denying you the pleasures she’ll never experience? She’s never even managed to enter her first instar, you know. Her kind are meant to be smothered in their cradles, not allowed to go around acting as if they’re real people.”

I felt a spike of discomfort from behind me. Mark didn’t like the things she was saying, for some reason. That might be worth looking into later. I was going to need allies among the cuckoos if I was going to get out of here in one piece.

“You people keep using that word, ‘instar,’” I said. “I know it means the space between metamorphosis, but I don’t understand what you think it has to do with me. I’ve never spun a cocoon or cracked my exoskeleton. I’ve only ever been me.”

“Those are activities for insects, and we’re not insects; not anymore,” said the woman. “I’ll make it a trade. If you can say my name, I’ll tell you what an instar is.”

“I don’t know your name.”

“Telepath, remember?” She cocked her head, a gesture that was familiar enough to be upsetting. I did that same thing when I was annoyed. So did Mom. It was clearly a family trait; it was just that the family was bigger than I’d ever thought.

“Right.” I narrowed my eyes and drove my thoughts forward, trying to break into her mind.

I bounced off her shields almost immediately. They were tightly woven, so interlocked and unstable that trying to slide past them was like trying to wrestle with the wind. Every time I grabbed for a weak spot, it reinforced itself, becoming twice as thick and three times as complicated. I breathed in, breathed out, and pulled back, “looking” at the shifting walls of thought and intention.

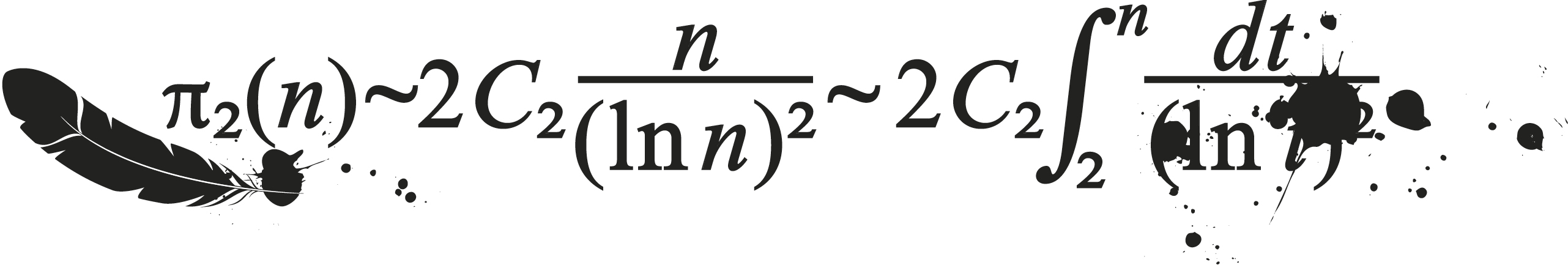

Math is the underpinning force of the universe. That’s something people don’t always understand when I try to explain it to them, and it’s so basic—so primal and perfect—that I don’t have the words to make it any clearer. How do you explain air to a bird, or water to a fish? There’s no explaining things that simply are. That’s how I feel about math. Math is everywhere. Math is everything. Even the seemingly effortless, uncomplicated things like walking and breathing and, yes, telepathy, they’re all math.

The other cuckoo’s mental shields were made of instinctive equations, so tightly knotted together that they seemed like a single continuous piece. They weren’t, though. An equation that large would be clumsy, awkward . . . slow. Her shields were fast and adaptive because they were built like a living thing, with numbers in the place of single cells.

Where there’s an equation, there’s an answer. I cocked my head in imitation of her earlier gesture, picking at the wall until it all came into sudden, perfect focus. I wrapped the answer to her equations in a soft shell of my intentions and lobbed it at the shields.

They went down all at once, a cascade of falling defenses. The whole process had taken only a few seconds. Back in the real world, outside our minds, the other cuckoo gasped, hand clutching at her swollen belly. The last of the shields fell. I looked at her levelly.

“Your name is Ingrid,” I said. “Now what the hell’s an instar?”

“Get out of my head,” she hissed.

I pulled back, enough that I was looking at her with my eyes more than with my mind, and said, “I met your conditions. I learned your name. It’s your turn to answer my questions.”

“She has you there,” said Mark.

“He’s on her side now,” said Heloise, in a jeering tone. “They went for a long, romantic walk in the woods together, and now he’s ready to switch to the winning team.”

“He’s already on the winning team,” said one of the male cuckoos in the back. The other male cuckoo said nothing, only sat in sullen silence, his mental glare overflowing the RV until the air felt like it was too heavy to breathe.

I did my best to ignore the lot of them, focusing instead on Ingrid. “Tell me what I need to know,” I insisted. “I know enough to know that I don’t know enough. Unless you’d rather I went in and took it . . . ?”

“No,” she said sharply, raising one hand in a warding gesture. The other hand remained clamped to her belly, cradling its precious contents. “You won’t take anything. But I can show you, if you’ll accept the knowledge. No forcing your way in. No digging for anything I haven’t offered willingly. Do we have an arrangement?”

There was fear in her words, lending them a spicy brightness that hadn’t been there before. I wanted to hear more of it, I realized; I wanted to hear her beg. That wasn’t like me. That didn’t change how much I wanted it.

Something was wrong. “Yes,” I said, and swallowed, suddenly dry-mouthed. “But you have to promise me the same. No looking at things I’m not intentionally showing you. No digging around.”

“The compact is sealed,” she said, and her eyes flashed white, and I was falling.

The infant cuckoo was pulled, purple-gray and squalling, from its mother’s womb. It kicked its tiny legs and thrashed its tiny arms until its father passed it into its mother’s arms, allowing her to guide it to her breast, where it latched on and started sucking greedily. Unlike a human baby, it seemed to know immediately what to do and how to do it.

“We have no instincts left,” said Ingrid. I turned my head, unsurprised to see her standing next to me. “We don’t need them. Everything an infant cuckoo needs to know is passed down, parent to child, before birth. They’re passive receivers in those days, unable to talk back, only able to learn.” She caressed her own swollen belly with one hand. “They stay passive for a week, maybe two, after birth. Long enough for us to be sure they’re whole and healthy before we pass them on. It’s not cruelty that makes us find better homes for our children. It’s mercy.”

“My parents left me with human strangers,” I said. “They died.”

“Yes, and that’s very sad, but it had to happen,” said Ingrid. The little family in front of us jumped forward, the man disappearing, the woman going from naked in her bed to clothed and composed and walking calmly up a driveway in a nice suburban neighborhood, a swaddled baby in her arms. “Babies are larval, you see. They’re easily influenced, easily changed. We give them everything we can before they’re born, and then we place them with hosts who won’t be able to manipulate them. We protect them by allowing them to incubate in peace. Larvae give off a sort of a . . . signal, like those wireless fences people buy for their dogs. No one can see that anything’s wrong, but the dog won’t cross the invisible line. Well, adult cuckoos won’t go anywhere near an infant that’s old enough to have started radiating, not before they’ve reached their first instar. Our children are safe from us. They claim and keep territory just by existing.”

“Are you going to abandon your baby?”

She looked at me like I was dim. I realized, numbly, that I could read her expression perfectly. It was just like being back in Artie’s mindscape. Here, everything was thought, and I could visualize it all without even trying.

“Of course I am, you stupid girl,” she said. “This isn’t my first, and it won’t be my last, if I have anything to say about it. I’m a wonderful mother, by the standards of our kind. I create them, I nurture them, I birth them, and then I let them go. Can you swear to me that you’d do half as well?”

“I never really thought about it,” I admitted.

“Of course you didn’t. You’ve been living with another species, living with another species’ rules. We don’t keep our children with us because we’re bad for them. They’d never become their own people if we kept them. They’d grow into little mirrors of their parents, because we’d be inside their heads every hour of every day, keeping them from becoming anything else. We love them, so we leave them. We give them a chance.”

I’d never considered the way cuckoos abandoned their offspring in quite that way. I twisted my fingers together, watching as the mother cuckoo rang the doorbell, smiled at the woman who answered, and stepped inside, out of view. Then I frowned.

“What about the families you leave the babies with? Do you give them a chance?”

“Why would we do that?” The scene shifted again, a discarded bicycle appearing on the lawn, a few bright stickers appearing in the window. The door banged open and a little girl ran out, pale-skinned and black-haired and identical to every other cuckoo child in the world. “There are so many of them. They’re predators, and they’ve overbred their habitat to a degree that would be appalling in anything else. If every cuckoo in the world had a baby every year, we still wouldn’t have a large enough population to threaten human superiority. Who died and gave them this entire planet? Oh, right. The dragons.” Her laughter was high and bright and giddy, like she’d just made the best joke the world had ever known.

The little girl grabbed the bike and maneuvered it up onto its wheels. Ingrid sobered.

“She’s larval,” she said, indicating the girl. “She has perfect camouflage at this age. All her telepathy does, ever, is convince the people around her that she belongs. It doesn’t revise them. It doesn’t tell them ‘this is your daughter.’ It just makes it so that when she skins her knee, they see blood; when she goes to the pediatrician, the doctor finds a heartbeat. This is a normal part of our development. It’s meant to last until the start of puberty. Trauma can trigger the first instar early. Do you remember when your first set of parents died?”

I swallowed, not looking at her. It was easier to focus on the child, who was bright and happy and fictional and uncomplicated. She was walking the bike toward the street, both hands on the handlebars.

“I don’t remember them at all,” I said quietly.

“No. I suppose you wouldn’t, not after what that butcher did to your mind.”

“Don’t talk about my mother that way.”

“You’ve had three mothers. The one who gave you away to save you, the one who died, and the one who stole you. I’ll talk about the third any way I like. She had no right. She stole everything you had, and she made you thank her for it.” Ingrid’s anger was a stinging swarm of gnats, swirling through the thoughts that shaped the illusion around us. “Children are supposed to come to their first instar in their own time. They grow, they mature, and one day, the little egg inside them breaks, and they see the world for what it is.”

The girl with the bike seemed to age five years in the blinking of an eye. She straightened, the suddenly too-small bicycle falling from her hands, and turned to look at the house with a thoughtful eye.

“That egg contains everything they need to know about being a cuckoo. It tells them what they are and where they came from. It tells them what’s going to happen to them, how to survive it . . . how to adapt.” The girl—the teen—walked back into the house, shutting the door behind her.

Someone screamed. A splash of blood hit the window. I flinched.

Ingrid was untroubled. “The entry into first instar can be a trifle violent, it’s true, but it’s a natural part of our development. The individual gets overwhelmed by the weight of the collective memory of a hundred generations, but not forever. They always resurface.”

“It turns them evil,” I said.

“It reminds them that they’re predators, surrounded by predators who wouldn’t thank them for pretending to belong,” said Ingrid. “The average age for metamorphosis from larval to first instar is thirteen. Your morph was delayed. Severely. That woman—the one you call your mother—had no right to steal your future from you.”

“She stole nothing,” I said. “She made it so I could care about other people.”

Ingrid turned to look at me, weary regret written clearly across her face. I was suddenly glad I couldn’t normally read expressions the way humans did. It was exhausting, looking at people and knowing what they were thinking, even if I wasn’t reaching out to read their minds. Telepathy was kinder.

“Who told you we don’t care about other people?” she asked. “Yes, we care more about ourselves than we do about humans, but humans care more about humans than they do about anyone else. Why are the rules different for them? Because they have the numbers? Because that means they get to decide what’s wrong and right? She took your past away. She reached into your head with bad tools, broken tools, and she sliced out everything that should have been yours.”

Something about that seemed wrong. I fought the urge to take a nervous step backward, and said, “Mark said I was on my third instar. How is that possible, if I never had my first?”

“Oh, you had it. It just took years. It should have happened almost instantly and unlocked all the answers to your questions. Instead, it unspooled day by day, making its changes a little bit at a time. We get stronger after a morph. It changes the configuration of our minds. It makes them deeper, more complicated. We can do things after a morph that we couldn’t do before.”

I thought uneasily of the way my telepathy had strengthened as I got older, until what had been a trial when I was a child had become easy, even casual. Had I been going through an instar? If we’d been taking regular scans of my brain, what would we have found?

“Most of us go through metamorphosis into our first instar and then stop. First instar is necessary. It’s what changes a larva into a worker. We’re industrious. We keep ourselves busy. And we very rarely need second-instar soldiers to keep us safe. Second instar is a matter of necessity. Few of us survive the morph to reach it. Those who do find themselves substantially stronger and more versatile than a first-instar worker. You have no idea what you’re capable of now, do you? That woman,” and the venom in Ingrid’s voice was startling, “stole your first instar from you, and she sliced your second up and spoon-fed it to you in little pieces, and now you’re lost. You don’t know how to be a proper cuckoo. You don’t know how to be a proper soldier. But that’s all right. You were never meant to be a soldier.”

“What are you talking about?” I couldn’t stop myself from replaying the conversation with Evie, where she’d explained what the doctors had seen on my MRI.

Ingrid saw it, too. She nodded solemnly, looking distantly pleased. “That was your second instar,” she said. “The channels are deeper for you now than they were before. First instar is automatic. Second instar is triggered by the self. Third instar is triggered from the outside. Fourth instar is a myth and a destiny and a sacrifice, and you’re going to do so amazingly well, my dear. You’re going to make me so proud, and I’ll name this little girl ‘Sarah’ in your honor. You’re going to be magnificent.”

“I don’t want this.” I took a step back, or tried to; we were inside Ingrid’s mind, still, and she refused to let me move. “I just wanted you to explain things to me.”

“I am,” she said, and leaned forward, and kissed my forehead. Her lips were so cold they burned. I shuddered, and she whispered, “Fourth instar is what shows you the numbers outside the equation.”

Then I was falling again, and everything was darkness and burning, and I couldn’t hold on. I tried, I tried, I screamed as loud as I could into the void, and the void was blazing white, the void was a supernova of absolute absence, and there was no one to hear my screams, and everything was everywhere, and everything was gone.