Twenty

“No matter how much we study, train, and prepare, there will always be situations we weren’t ready for. That’s the nature of reality. It’s sort of neat, when it isn’t trying to chew your face off.”

—Kevin Price

Someplace that probably isn’t safe for incubi or other living things

EVERYTHING WAS WHITE.

I turned slowly, trying to get my bearings in the infinite brightness. There were no walls, no floor, no ceiling: only the featureless sterility of a blank page, waiting to be transformed into something comprehensible by the addition of basic physical forces.

I cupped my hands around my mouth. “Hello?” I shouted. There was no echo. My words barely seemed to travel past my lips, like even sound was being swallowed by this terrible new landscape.

Panic seemed like a good idea. Panic often seems like a good idea. Unfortunately, experience has shown that panic is virtually never a good idea, and if it is, it’s because you’re already about to die, so why waste time on staying calm? I forced myself to take a deep, slow breath, in through my nose and out through my mouth. The panic receded a bit. I did it again. Then I paused, panic forgotten in the face of a new oddity. I breathed into my cupped hand and sniffed.

Nothing.

Most of the time, Lilu pheromones are virtually undetectable, which makes sense: if people could smell us coming, they’d do a much better job of avoiding us, and hunters like the Covenant of St. George would probably have eradicated us centuries ago. They get stronger when we’re nervous—and I was definitely nervous. That’s part of why I wear so much crappy cologne, and why Elsie has an addiction to small artisanal perfume companies. The Black Phoenix Alchemy Lab has saved a lot of people from becoming embarrassingly enamored of my succubus sister.

When our pheromones are detectable, they smell vaguely sweet and woody, like crushed aconite flowers mixed with sugar. And when I breathed into my hand, I couldn’t smell them at all. There was nothing, not even the chemical tang of the cologne I use to smother them. I might as well have been a baseline human. Which was something I’d dreamed about my entire life but wasn’t something I’d really been hoping would happen during an attempted rescue.

Something was wrong.

“As if the big white room didn’t tell you that part,” I muttered, and started walking. It wasn’t necessarily the right thing to do, but it was something to do, and that made it better than standing around waiting for the invisible floor to drop out from under my feet and send me plummeting into the void. I am not a big fan of plummeting. If I had to commit to a position, I’d probably have to say that I was anti-plummeting.

I kept walking, and a smudge appeared on the horizon. Appeared with the horizon; until there was something to break up the infinite whiteness of it all, there couldn’t really be said to be a horizon. It needed something to define it. I started walking faster.

The smudge began to take geometric shape. It was a half-circle of blackboards, pushed together like a soundstage from a movie about mathematicians trying to save the world. There was a figure there, standing in the middle of the broken ring. I was too far away to make out details, but I could see that they were wearing an ankle-length skirt and a virtually shapeless sweater, the sort of thing that was more warm than fashionable, that would protect the wearer from notice.

I broke into a run.

The closer I got, the more details I could see. The figure became a woman became a cuckoo became Sarah, chalk smudges on her nose and chin, lips drawn down in the so-familiar, so-beloved expression of pensive contemplation that she’d been wearing since we were kids sitting and coloring at the same table.

(Well, I’d been coloring. She’d been doing calculus in crayon, and when we’d finished, Aunt Evelyn had pronounced us both to be amazing artists and hung our projects side-by-side on the refrigerator.)

“Sarah!” I sped up. I wasn’t winded at all, which was, like the lack of my pheromones, probably a bad sign. There was a decent chance I was dead, and this was the afterlife, although if that was the case, my Aunt Mary had way underplayed how much eternity sucked.

Sarah didn’t turn. She kept writing figures on the chalkboard, moving at a steady, unhurried pace, like she had all the time in the world. Which was probably true—if we were dead.

Maybe this was the cuckoo afterlife, and I’d been pulled into it because I’d been touching Sarah when—what? When the other cuckoos caught up with us and forced Elsie to crash the car? But that didn’t make sense. Not only had Elsie still been wearing her anti-telepathy charm, but if Mark had been telling the truth—about anything—the cuckoos were going to want Sarah back. She was their key to escaping this world and this dimension and moving on to someplace that wasn’t prepared for them. Which meant Sarah wasn’t dead. Which meant I wasn’t dead.

It was a bit of a relief to realize that this probably wasn’t the afterlife. I know several ghosts personally—I have two dead aunts who I love a lot—but that doesn’t mean I want to bite the big one before I see the next season of Doctor Who. But if we weren’t dead . . .

“Uh, Sarah? Are we inside your head right now? Because I don’t think I’m supposed to be inside your head.”

She kept writing figures on the blackboard, not looking at me.

“Are you ignoring me, or can you not hear me? I mean, we’re in a funky infinite whiteness, which is really Grant Morrison-esque and a little bit upsetting, so I’m trying not to think about it too hard, and I guess that could mean your perceptions are filtering me out, but I’d really like it if you’d talk to me.”

She kept writing.

“Sarah?” I touched her shoulder gingerly. “Sarah, it’s me. It’s Art—”

She turned her head, not all the way, but far enough for me to catch the sudden flash of white in her eyes. I was knocked back immediately, going sprawling on the floor that wasn’t a floor, landing hard enough to take my breath away. Sarah returned her attention to the chalkboard.

“Okay, that’s not good,” I muttered, pushing myself to my feet. “Come on, Sarah, you need to cut this out. Telekinesis? Really? When did you figure out how to move things with your mind?”

Was it my imagination, or did the corner of her mouth twitch? Since we were probably inside Sarah’s head right now, I wasn’t sure whether I actually got to have an imagination. Telepaths are really confusing.

More carefully this time, I began walking back over to her. “Do you know what’s going on? Because I’m not going to lie to you, this shit is weird, and it’s getting weirder all the time. I think we need to get out of here.”

Sarah kept writing.

“I’m afraid if I touch you again, I’ll get knocked across the—this isn’t exactly a room, you know. More a featureless void. Please don’t knock me across the featureless void. It’s not fun. I didn’t enjoy it the first time. I’m sort of worried that I might just keep flying away from you forever, since there’s nothing to stop me. How is gravity even working here?”

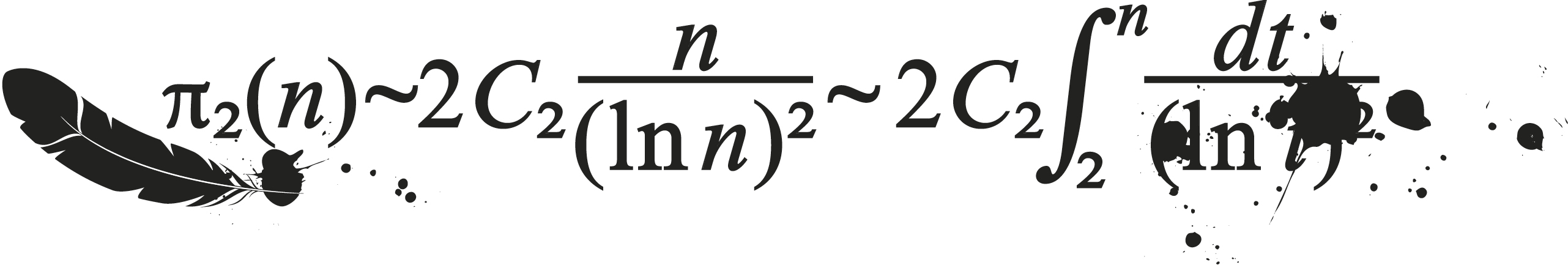

Again that twitch, before she went placidly back to writing on her blackboard. I turned to face it. The numbers—well, partially numbers; her idea of math involved more letters than a bowl of alphabet soup—were arrayed in straight lines, broken here and there by little squared-off chunks of text that had been written smaller, like they were supposed to be the algebraic equivalent of a footnote. None of it made any sense. That wasn’t new.

What was new was the way some of the strings of numbers seemed to phase in and out of reality, like they were too tightly written to maintain their grasp on a single linear plane. I squinted. They kept moving.

“This is bad.”

Sarah kept writing.

“Look, I get that you’re in a smart-person fugue and all, and normally I wouldn’t bother you while you were undermining the fabric of the universe with mathematics, but you do understand that this is bad, right? Numbers shouldn’t be sufficient to change the laws of physics. They should sit quietly and think about what they’ve done until it’s time for someone to figure out the tip.”

Sarah kept writing.

“Dammit, Sarah, you’re going to kill us all if you don’t stop.”

Sarah stopped.

So did I, just staring at her for a long moment, until I saw her hand—still holding the chalk—begin to shake. It was a small, almost imperceptible tremor. I decided to take the risk and reached out to carefully pluck the chalk out of her fingers.

She didn’t resist. She also didn’t fling me telekinetically away. I was willing to take that as a win.

“Can you hear me?” I asked.

She stared at the chalkboard and didn’t reply.

“Sarah, if you can hear me, it’s really me. It’s Artie. We’re not dead, so I think . . . I think this is your mindscape, and you’re in the middle of what the other cuckoos called your metamorphosis. You’re entering your fourth instar, which means you’re becoming a better cuckoo. Bigger and stronger and everything. I’m really here. I’m with you in the real world, where your body is, and I’m touching you, and I think that was enough to let you pull me in with you. If you can hear me, please. Look at me? Say something? Say anything. I want to help you. I need you to tell me what you need me to do. I need you to tell me you’re still . . .” I trailed off. There were no good endings to that sentence.

Sarah lowered her chin, until she was looking at the very bottom of the chalkboard, and said in a low voice, “I know you’re just me trying to talk myself out of this, but I have to do the work. If I don’t do the work, I don’t wake up, and I don’t go home. There’s no part of me that doesn’t want to go home. There’s just all the parts of me that are too scared to believe that I can finish things. I can. I swear I can.”

“Sarah, please.” I dropped the chalk and grabbed her hand, only wincing after I was already fully committed to the action.

The repulsion blast I was expecting didn’t come. I relaxed a little. Then Sarah raised her head and looked at me, and I relaxed substantially more.

“You’re not real,” she said softly. “I wish you were real. It would be so nice if you were real. But you’re not real, and it’s not fair of me to act like you are.”

“Hey, that’s sort of mean,” I said. “After everything I’ve been through today, the least you could do is admit that I exist. I mean, you’re the one who got kidnapped.”

“I wasn’t kidnapped,” she said. “I went because . . . because I had to. It was the only way to keep the family safe.”

“Oh, sure, you call it ‘keeping us safe,’ like there was ever a chance that we weren’t going to go after you,” I said. “Mark told us how he lured you out of the compound. He’s sort of an asshole, by the way. In case you were thinking he might be your new best friend, since he’s the same species as you and everything. I can’t say that he’s someone I want to invite to join us for D&D.”

“Mark?” Sarah raised her eyes, enough to blink at me in clear bewilderment. “You met Mark?”

“Black hair, blue eyes, total asshole? Yeah, I met him. I know it’s cool for you to have other friends, but could you try having other friends who don’t want to kill us all? Maybe?” I shook my head. “No, that’s not fair. He’s helping us. He has a sister who’s not a cuckoo, and apparently if your species can convince you to work for them, she’ll die along with the rest of us.”

“You met Mark,” she repeated, sounding faintly baffled. “You’re really you.”

“I’ve been saying that.”

“But you can’t be here.” Her eyes widened. She took a step backward. “Artie, what are you doing here?”

“I told you—I took off my anti-telepathy charm while I was holding you propped up in the backseat. Not my smartest move, since it means we were in skin contact before I realized what was happening, but I’m not sure I’m sorry.” I chuckled bleakly. “I was afraid you might not be you anymore. And now here you are, holed up inside your own head, doing math. We need to get you another hobby.”

“I have to do the math,” said Sarah. “The math is how I get out of here.”

I frowned. “What do you mean? Just open your eyes. Wake up. There’s no reason you can’t.”

“It’s a physical process, Artie.”

“What is?”

“Metamorphosis.” She looked back toward the chalkboard, and for a moment—just a moment—I could see the raw longing in her expression, like she had never seen anything so beautiful. “This is like taking a final exam. I have to pass the class before I can graduate and go on to the next one.”

“What happens if you don’t? Can’t you just . . . wouldn’t that mean you repeated the class you’d already taken? Wouldn’t that give us more time?”

“That’s where the metaphor falls apart. Haven’t you ever seen a butterfly who couldn’t finish breaking out of the cocoon? They die, Artie. They get stuck, and their wings can’t straighten, and they die.”

“Are you saying you’re trying to grow wings?”

“I’m saying that if I don’t finish breaking out of this cocoon, I’m pretty sure I won’t survive.” She looked back to me, resignation and grief in her expression. Then she smiled. “You know, I think the best thing about meeting on a mindscape is being able to see your face. I never do out in the real world, not unless it’s in a photograph. You’re really pretty. Did you know that? I’m glad I know that.”

“Um.” I reached back and rubbed the back of my neck, or at least the idea of the back of my neck. Again, telepathy is confusing. “I don’t think it’s ‘pretty’ for me. Pretty sure it’s supposed to be ‘handsome.’ And either way, it’s not technically correct.”

“You have a skewed sense of your own appearance, which is common,” said Sarah. “I think you’re beautiful. Right now, I’m going to be selfish and say that’s what matters.”

“That’s not selfish.”

“Isn’t it?” Her smile was even sadder than before. “You can’t stay here, Artie. I need to be alone with the numbers. I need to focus on them right now. I need to show them that I can handle them.”

“They’re just numbers.”

“No. These numbers are different. These numbers are awake. They can see me, and they’re trying to decide whether I’m good enough to see them.” She glanced at the chalkboard, fingers twitching. Then she raised her hand.

The chalk pulled itself up off the floor and flew to her, smacking into her palm. She closed her fingers around it.

“I’ll be home soon, I promise,” she said. “The cuckoos can’t make me do anything I don’t want to do. I just need to finish this equation and I can come home.”

“Sarah—”

“Kiss me one more time before you have to go?” Her voice was soft, plaintive. There was no way I could have told her no. I stepped forward, pressing my lips to hers, and she melted against me, languid and slow. I could have kissed her forever. I wanted to kiss her forever, the rest of the world be damned.

Sarah was the one to eventually pull away.

“Don’t worry about me, Artie.” She looked at me, and her smile was heartbreakingly bright, and devastatingly beautiful. I couldn’t look at it. I couldn’t look away.

“Please,” I whispered. “What you’re trying to do will destroy the world.”

“It won’t. Ingrid said—”

“She’s a cuckoo. Cuckoos lie.”

For a moment, I saw doubt in her eyes. “I’m a cuckoo. Do you think I lie?”

“Not to me,” I said.

“I’ll be fine,” she said, and her eyes flashed white, and everything went black.

I sat up with a gasp, feeling the heavy weight of gravity settle over me, along with a dozen sensations I hadn’t realized were missing—the whisper of the night wind, the cool dampness of the air, the looming shadow of the sky, which was considering whether or not it was time to rain. In Portland, the sky is always considering whether it’s time to rain.

“Good,” said Elsie. She was bending over me, her hands on her knees, an uncharacteristically solemn expression on her face. I could see the lights of the compound behind her. It looked like the whole house was lit up, even the rooms that were usually left closed-off unless more of the family was in residence.

Elsie’s finger jabbed at the center of my chest, jerking me back into the moment. “I thought you were dead, you asshole.”

“I told you he was still breathing,” said Sam.

I craned my neck back. He was standing behind me, arms crossed, still in his vaguely simian form. His tail was wrapped tightly around his left leg, like he was anchoring himself in place.

“What . . .” My throat was dry. I swallowed hard and tried again. “What happened?”

“You dropped your charm and went down, dude. It was like someone had flipped your switch or something.” Sam shook his head. “We couldn’t figure out how to peel you off the cuckoo without touching her, and with the way you’d gone down, we were sort of worried you’d jerk us into whatever hallucinatory Wonderland you’d gone and tumbled into. So we left you alone until we got to the house.”

“So how . . . ?”

“I opened the car door and unbuckled your seatbelt, and you fell out of the car,” said Elsie. “You didn’t wake up, so I stuffed your anti-telepathy charm into your pocket. That did the trick. And before you ask, Annie took Sarah inside.”

Then she hauled back and kicked me in the hip.

“Hey! Ow!” I put my arms up to block my face, just in case she had some wacky ideas about continuing her assault. “What the fuck, Els?”

“Never, ever, ever do that to me again, you asshole.” She dropped to her knees and wrapped her arms around me before I had a chance to respond, yanking me against her and burying her face in the front of my shirt. Her shoulders moved in uneven little hitches. I realized, to my dismay, that she was crying.

My badass big sister who could handle anything the world wanted to throw at us was crying.

“You’re not allowed to leave me,” she said, voice muffled by the way her head was bent, the way her lips were pressed to my shirt. She sounded . . . small. It was terrifying. “I thought you were going to leave me.”

“I’m right here,” I said, and awkwardly patted her hair. “I haven’t gone anywhere.”

She pulled back, letting go so she could look at me, and offered me a wan smile. I’m sure mine was just as bad, because we both knew the terrible truth behind my answer: one day, one of us was going to leave. One day, one of us was going to wind up in a situation we couldn’t bluff or bully our way through, and we were going to become one more entry in the litany of the dead that the Aeslin mice recited twice a year, on the summer and winter solstices. That’s what it means to be a Price. We fight. We do our best to win. But eventually, inevitably, we lose.

Sam was still standing behind me, silent and awkward as he watched his girlfriend’s cousins try to comfort one another, and it was hard to swallow the urge to turn around and tell him to run for the hills as fast as he possibly could. Annie loved him and he loved her and if there’s one thing that every Price child learns before we graduate from high school, it’s that love is never enough. Grandma Alice loves Grandpa Thomas, has for more than fifty years, and what did that get her? An endless search through parallel dimensions for a man she can’t let herself admit is dead. And she’s the lucky one. At least she can pretend to have hope. For the rest of us, hope is something that dies quick and messy on the battlefield.

Sarah was fighting her own battle right now, trapped in the white nothingness of her own mind, and there was nothing that any of us could do to help her, and there was nothing that I could do to save her. All we could do was wait . . . and hope that she found a way to win.

I remembered the bleakness in her eyes right before she’d thrust me from her mindscape. Assuming that had been real, and not just a weirdly specific hallucination, I wasn’t as certain as I wanted to be that she was going to come out on top. The cuckoo equations were eating her alive.

Gingerly, I pushed Elsie away from me and climbed to my feet, relieved when my legs didn’t take the opportunity to collapse out from under me. The world spun a little before settling down. Elsie watched me, wary, waiting for the moment when I’d fall.

“You were out for more than half the drive,” she said.

“It didn’t feel that long,” I said. “Come on. Let’s get inside. I’m sure we’re about to be yelled at.”

“I’m not.” Her expression was grim as she stood and brushed the grass off her knees. “Normally, sure, but normally, we haven’t come racing back with a cuckoo in a coma and word of a whole hive behind us. This is war. Lectures about our malfeasance can wait until later.”

“This is a swell family that I’ve decided to attach myself to,” said Sam. “Totally normal. Way better than the carnie life.”

“You said it, not me,” said Elsie, and started for the house, leaving the two of us with no real choice but to follow.

Mom, Aunt Evie, and Uncle Kevin were all in the living room. Dad, Annie, and James were nowhere to be seen. Neither was Sarah. They had probably taken her upstairs to her room, where she could hopefully sleep without fear of the cuckoos finding her. That didn’t make her absence any less distressing.

Mom surged to her feet as soon as she saw us appear in the kitchen doorway, almost knocking Uncle Kevin over in her rush to reach us and wrap her arms around our shoulders, crushing Elsie and me both against her for one long, desperate moment. Then she released us and shoved us backward at the same time. I bumped into Sam. Elsie hit the counter.

“What the hell were you thinking?” Mom snarled. For a moment, I could see why so many cryptids considered her one of the more terrifying members of the family. She mostly doesn’t do field work—that whole “not wanting to wind up dead” thing she has going on, which honestly, I agree with—but when she does, she has absolutely no chill. Aunt Evie will try to empathize. Uncle Kevin will try to negotiate. Mom will just stab first and ask questions never.

“That we needed to get Sarah back,” I said, voice cracking in the middle of the sentence, like my mother’s disapproval had somehow hurled me all the way back into puberty. “We didn’t have a lot of time, and you were all arguing about the best way to do this. I couldn’t wait any longer.”

“Arthur James Harrington-Price, did your father and I raise you to be a fool?” Mom took a step forward, virtually looming over me. It was a nice trick, since I’m taller than she is. “Because rushing in with minimal backup is the definition of foolishness.”

“No, it isn’t,” I snapped, and stepped forward, toward her. It was like our heights reversed in an instant. Now I was the one looming. “I took a sorcerer, a fūri, and a succubus who drives like she’s auditioning for Mario Kart, all equipped with anti-telepathy charms, assisted by a cuckoo who was willing to betray his own kind for the sake of saving this world, and I got Sarah back. Honestly, I would have been happier if I could have taken fewer people, because it wasn’t like we were ever going to have a pitched battle in the middle of Beaverton. We needed to get in, find her, and bring her home. We did that.”

“Artie . . .” Her face softened. “You know she’s not well.”

“He’s not stupid, Aunt Jane.”

We all turned. Antimony was standing on the stairs, her hair sticking to the sweat on her cheeks and forehead, a terrifying calm in her expression. She looked like someone who had come to deliver the news of a death to a family. My heart clenched.

She looked at me as she said, “Sarah’s in the middle of what the other cuckoos called a metamorphosis, and when she wakes up, there’s every chance she wakes up being driven by an equation so large that it breaks the brains that try to hold it. She’ll be a fourth instar cuckoo. She may not be Sarah anymore, at least not the way that we think of her. And we may need to make sure she doesn’t crack this world open like an egg. Artie knows all of that. He knew it before we went to find her. But he also knows that we’re family.”

“She’s right,” said Aunt Evie. “I hope and pray that Sarah can fight this—that she’s more Price than cuckoo. But if she can’t, it’s better that we be the ones to stop her. It’s better that it be her family.”

She was talking about killing Sarah. That was what this really came down to. She was talking about taking a knife and driving it into the base of Sarah’s skull, where it would sever her brain stem and kill her as quickly and painlessly as possible. Cuckoos don’t have the same arrangement of internal organs and weak spots as true mammals. The fastest, cleanest way of taking them out is by targeting the brain.

The thought was enough to make my stomach churn, especially since I couldn’t say that they were doing anything wrong. If it came down to a choice between Sarah or the world, we would choose the world. We wouldn’t have a choice.

“Where’s Dad?” I asked.

“Out in the barn with James,” said Uncle Kevin. “They’re trying to get the cuckoo we captured earlier to talk. The one you didn’t lose.”

“We didn’t lose Mark,” I said. “We just . . . didn’t bring him back.” If he had any sense of self-preservation, he’d already be on his way home, returning to the sister he loved and the parents he liked well enough to keep alive.

I somehow didn’t think the cuckoos would be very forgiving of his role in our recovering Sarah.

“That sounds like losing your hostage to me,” said Mom.

“Yeah, well, we had to do something, or we wouldn’t even be having this argument.” I shook my head. “I’m going out to the barn. Maybe Heloise knows what we can do to save Sarah.”

“Artie.”

I stopped and looked at Elsie, raising my eyebrows in unspoken question. She looked back at me, earnest and clearly grieving.

“What happens if she says there’s nothing we can do?”

Again, my stomach roiled. I somehow kept my voice calm as I replied, “Then you take the mice into Sarah’s room and you make sure they see everything. She’s a part of this family. She’s going to be remembered.”

This time, when I started walking, she didn’t stop me. Nobody did. I made my way across the living room and down the hall to the back door, letting myself out into the cool night air. My feet left clear impressions in the dewy grass as I made my way to the barn.

Inside, Heloise was still strapped to the table, and Dad was sitting nearby, the can of Raid in his hand. James was standing over the captive cuckoo, fingers spread wide, like he was soaking up the heat from a campfire.

“What’s he doing?” I asked.

Dad glanced over at me, and I saw the flicker of grief in his expression before he clamped it down and said, with merciful neutrality, “Testing to see how much cold a cuckoo can endure before it starts talking. They can apparently survive in sub-arctic temperatures, which is pretty impressive. There must be something strange about their musculature. We’ll pay close attention when we analyze the tissue we got from that other one.”

“This is boring,” said Heloise. She turned her head and smiled brightly in my direction. “Well, well, well, if it isn’t the little half-incubus. I didn’t expect to see you so soon. Or ever, really. The hive should have torn you apart.”

“Annie’s back,” I said. “I bet cuckoos like heat a lot less. Sarah hates the middle of the summer.”

Heloise’s smile flickered, turning wary. “You wouldn’t.”

“You know, my family thinks I’m the nice one, because I spend most of my time in my room and I don’t bother people unless I have to, and because I think it’s not fair of me to use my pheromones on standard humans. They didn’t ask to share the planet with a bunch of people who look like them but aren’t them. This isn’t the X-Men.” I made my way to one of the trays of tools that had been set out for the first cuckoo’s necropsy. There were several scalpels of varying size and sharpness. I selected one of the larger ones before turning back to Heloise.

She was still watching me. She wasn’t smiling anymore. Not even a little bit. I started walking toward her, the scalpel in my hand.

“They think I’m the nice one because I don’t give them any reason not to, but you know who never thought I was the nice one? Sarah. That’s part of why we get along so well. She’s always known that I could be really dangerous if I wanted to. I never wanted to. I just wanted to read comic books and play with my computer and love her. Even if I never told her I loved her, being able to do it was enough.”

“I didn’t do anything,” said Heloise hurriedly. James had closed his hands and stepped back, expression going politely neutral. He wasn’t going to stop me from whatever I wanted to do next. That was good to know.

“I think we might disagree there,” I said, stopping next to the table. I lowered the scalpel until it was pressed, lightly, against the skin above her collarbone. I wasn’t pressing down—not yet—and she wasn’t bleeding, but she would be soon enough. Skin, whether human or cuckoo, is easy to cut, and difficult to heal. “We got her back.”

Heloise’s eyes went even wider. “What?”

“We went to your hive, and we were careful, and we got her back. She’s here now, in a room that’s warded against your little telepathic tricks, so the other cuckoos can’t hear her.” I pressed down slightly on the scalpel, until the blade was indenting her flesh. “Here’s a fun question for you: why would I tell you this, knowing that you’ll just broadcast it all to any cuckoo who gets close enough to potentially help you? Got any ideas?”

Heloise couldn’t pull away from the scalpel, so she held perfectly still, staring at me. “You wouldn’t dare.”

“Why not? You’re not my family. She is. You’re just the monster that helped them hurt her.”

“Because I look exactly like her,” Heloise said, and for a moment, the smugness worked its way back into her voice. “You humans are so stupid. You can threaten me all you want, but you’ll never—ahh!”

Dad winced when she screamed. So did James. I raised the scalpel, blade now dripping with the clear lymph that serves cuckoos in place of blood.

“Want to say that again?” I asked. “You’ll look a lot less like her if I start slicing pieces off. It might be easier to look at you. So it’s not a bad idea.” I started to bend over her again.

“Wait!” Heloise looked at me with fear and misery in her eyes, and maybe it made me a monster, but I didn’t feel bad about putting it there. “What do you actually want from me?”

“I know Sarah’s in morph.”

“Yes.”

“Tell me how to stop it before she enters her fourth instar.”

Heloise blinked. Then she seemed to sag against the table, misery wiping every other trace of expression away. “You’re going to kill me,” she said. “I always knew that was a possibility. When Ingrid asked me if I’d be willing to be the decoy, she wasn’t really asking. She’s the strongest of us. Well. Was. When the little princess wakes up, she’ll be able to wipe her mother off the map. Too late for me. Sorry, Heloise. For a member of an inherently selfish species, you sure did die stupid.” She laughed, high and sharp and utterly mirthless. It was the laughter of someone facing the walk to the gallows and determined to do it without tears.

“I never said I was going to kill you,” I said.

“You didn’t have to,” she said. “You can’t stop a morph, little incubus. Once it begins, once that process kicks off, it keeps going until it’s over. Instars can last forever, depending on the external stimuli we encounter, but metamorphosis is a limited-time offer. She’s going to finish her transformation and she’s going to wake up in her fourth instar and she’s going to blow this stupid planet to kingdom come. Sorry. Guess that’s probably pretty inconvenient for you. Look at it from my perspective, though: I’m about to be dead.”

“Destroying the planet will kill the rest of us,” said Dad. I flinched a little. I’d been so focused on Heloise that I’d almost forgotten he was there.

“So what? I’m the one that matters.” She tilted her head back as far as the table would allow, glaring at him. “I’m the superior species. You filthy primates took the long route to becoming mammals, and you’re still disgusting. All that sweating and bleeding and listening to your own heartbeats like having a crappy diesel generator for a circulatory system is somehow a good thing. It’s vile. I don’t know how you live with yourselves.”

“I’m not going to kill you,” said Dad, voice mild. “You can stop trying to make me.”

“Oh, believe me, if I really tried, I’d get my way.” Heloise’s eyes flared white. “I don’t need to be able to read your mind to know what really scares you. That wife of yours. She’s human, right? Human enough, anyway. Does she love you? Or have you just overdosed her on those nifty pheromones you have?”

“Shut up,” said Dad.

“You’re not from around here either, you know. The dimension you came from may be closer than ours, and you may have arrived before we did, but this isn’t the world you evolved to exploit. You people and your high horses and your fancy morals, when you’re colonists as much as we are. We weren’t the first invaders. We won’t be the last. Or oops, I guess we will be, because when our queen comes out of her egg, she’s going to murder every last one of you fucking—”

“I said, shut up,” snapped Dad, standing. Looming, really, the can of Raid in his hand and a dire expression on his face. Heloise stopped talking, but she didn’t flinch. If anything, she looked absolutely, transcendentally triumphant, like she was finally getting what she wanted.

“You don’t know, do you?” She smiled like she’d just won something. “You can’t look into her head and see—and even if you could, maybe she doesn’t know. Maybe she thinks she loves you until she gets a head cold and realizes she can’t stand you when she can’t smell you. Are Lilu behind the push for free flu shots? Widening your target pool?”

Dad began to shake the can.

I dropped the scalpel, hurrying to put my hand on his arm. “No. Dad, no. You’re letting her control the situation. You can’t listen to her. She’s a cuckoo. Cuckoos lie.”

“All cuckoos? Because I seem to remember you making an impassioned plea for the life of one cuckoo in specific. Is she a liar, too? Or do you think you’re special? You’re not special, Lilu. You’re just one more pawn for her to push around the board. We can’t fight our natures, even when we want to. Biology always wins. Biology’s a bitch that way.”

“Mark fought his nature,” I said.

“Did he? Or did he convince you to save the fair maiden from her wicked, wicked captors and bring her right back into your nest, the way cuckoos always do? You’re protecting her while she finishes her metamorphosis. You’re sheltering your own doom, and you think it’s your idea because she would never lie to you, because she loves you.” The sneer Heloise put into the word “love” was enough to make my stomach turn over.

I swallowed bile. “It’s not like that.”

“It’s always like that, over and over and over again. You people renamed us when you realized we were here, called us ‘cuckoos’ like that would make us less, like that would make us weak enough for you to fight. Did you know that we returned the favor? We call you ‘cowbirds.’ You’re too stupid to see what’s in your own nest. You’re too stupid to see anything.”

“Right,” I said. “That’s enough.”

The anti-telepathy charm was still in my pocket. I dug it out, careful to keep it against the skin of my palm as I leaned over and slipped it under the neck of her sweater—Sarah’s sweater—and anchored it under the strap of her bra.

Heloise froze, eyes going wide once again as she stared at me. I offered her a cool smile. It didn’t matter whether she could see the expression or not. I knew it was there.

“I’m tired of you, but I’m not going to kill you,” I said. “Enjoy the quiet.”

“Please,” she whispered, sounding truly frightened for the first time. “It’s too much. The world. You turned off the world.”

“Yeah, I did,” I agreed, stepping back. “If Sarah doesn’t wake up, you’ll wish I’d done worse than that.”

I turned and started for the barn door. I was almost there when Dad caught up to me.

“That wasn’t kind,” he said, voice low.

“No, it wasn’t,” I agreed. “But then, what about this day has been?”

He rested his hand briefly on my shoulder. “I won’t tell you she’s going to be all right. None of us can know that. But I can promise that we’re going to do everything we can.”

“I know, Dad,” I said. “Come on. Mom’s waiting for us.”

Side-by-side, we stepped out of the barn and started across the lawn, toward the house where the rest of our family was waiting, where Sarah slept, where everything was falling apart.

Even me.