Nicholas I, who reigned from 1825 to 1855, was the last tsar profoundly to affect the evolution of the Hermitage. In December 1837 the Winter Palace was gutted by fire and the Hermitage pavilions, containing the imperial art collection, were only saved by the guards and palace servants who destroyed the two connecting passages, built a dividing wall between the buildings while the fire blazed and continuously doused it with water pumped from the frozen Neva and Moika rivers.

Nicholas had to rebuild and refurbish the palace. Luckily he seems to have inherited both his mother Maria Fedorovna’s interest in the applied arts, including architecture, and her clever artistic eye. His elder brother Alexander I had hired Alexander Sauerweid, Russia’s first important battle painter, to teach him drawing and painting and the examples of his work that have survived demonstrate that Nicholas had a definite talent in this field. On a loftier scale, central St Petersburg – Palace Square, the Admiralty, St Isaac’s Cathedral and the Senate – bear witness to his fascination with architecture. The sequence of magnificent Neoclassical buildings which linked the older palaces and completed the elegant symmetry of the city centre were all commissioned by Nicholas or his brother Alexander I, and completed under Nicholas’s eagle eye – he was a martinet of no mean order. His contemporaries called him ‘the rod’, referring simultaneously to his deportment and his dedication to corporal punishment.

He took a close interest in the reconstruction of the Winter Palace and, apart from the furnishings, most of its rooms have survived almost unchanged from his time. While the rebuilding was still in progress he had the idea of adding a purpose-built museum to the palace complex – the New Hermitage – which was cunningly tucked into a space between the Small and Old Hermitage pavilions. After he had moved the best of the imperial art collection into the museum in 1852, he commissioned the architect Andrey Stakenschneider to redecorate the interiors of the Old and Small Hermitages in flamboyant, historicist style. Stakenschneider’s white marble Pavilion Room at the Neva end of the Winter Garden is one of the finest expressions of this style anywhere, combining slim columns and arches borrowed from an Arabian mosque, medieval fountains and a Classical Roman mosaic.

Nicholas’s involvement with the interiors of the museum building went far beyond the normal relationship of sovereign and architect – in this case, Leo von Klenze from Germany. The Emperor oversaw every detail, from the choice of marbles, to the design and arrangement of the showcases. He chose the paintings that should hang there and he pooled the collections of antiquities spread around his other palaces to form the galleries of Greek, Roman and Scythian art. Major archaeological finds were made in the Crimea early in his reign and he saw that these discoveries were handsomely displayed in his new museum.

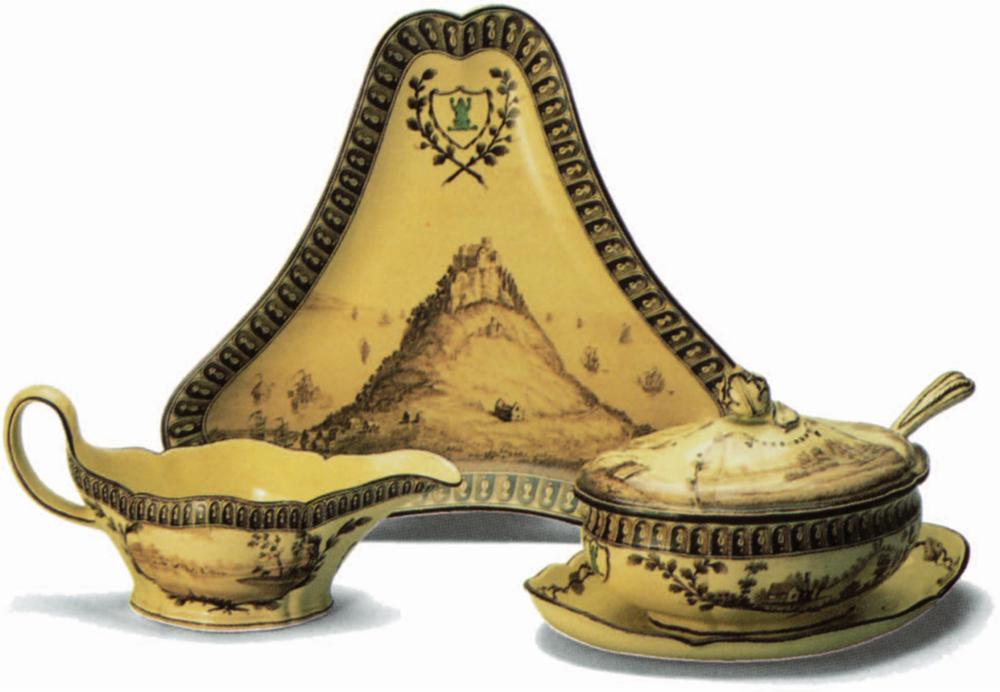

Nevertheless, Nicholas’s conviction that he knew what was best in every sphere – he regarded himself as God’s chosen representative in Russia – led to his making several eccentric, and some disastrous, decisions about the Hermitage collection. He sold off 1,220 paintings, some of them of the first importance; he had others destroyed. He melted down several of Catherine’s gold and silver dinner services, some 3,300 lb of metal in all, and had new ones made in a style he preferred. His London Service, which was intended to serve around fifty people and included 1,680 pieces, was ordered from Garrards, Hunt & Roskell, and other British silversmiths after his state visit to England in 1844. It included seven sculptural groups to decorate the centre of the table, one of them being a copy of the ‘Queen’s Cup’ which had been made for presentation at the Ascot races of 1844.

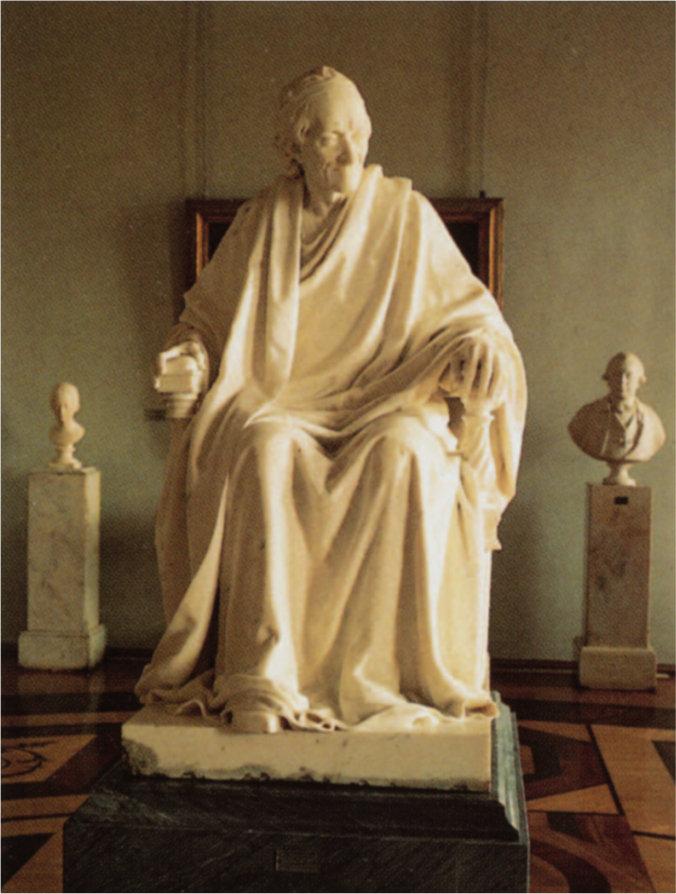

Nicholas dismissed Houdon’s great full-length statue of the seated Voltaire with the famous words: ‘Destroy this old monkey’ – luckily, his staff disobeyed him. The statue was first removed to the Hermitage library, where Nicholas, presumably, rarely ventured, and later in the nineteenth century, when the books themselves were sent to the Public Library on Nevsky Prospect, Voltaire went along for the ride.

Nicholas’s character as a ruler was profoundly influenced by the Decembrist uprising and the shock of its bloody suppression in the first hours of his reign. ‘No one can fully comprehend that burning pain which I feel and will continue to feel throughout the rest of my life whenever I remember this day,’ he told the French ambassador at the time. The Decembrist conspirators included the flower of Russian youth. There were thirteen sons of senators and seven of provincial governors; five were eventually executed and another 200 or so were imprisoned or sent to Siberia.

Nicholas was convinced that he was dealing with a highly organised plot aimed against the Romanov regime itself – with the conspirators maybe seeking to replay the French Revolution in Russia. He commissioned an in-depth investigation of the conspirators in order to understand, on the one hand, what might be wrong with the running of his empire that had provoked them and, on the other, how to prevent future insurrections. His investigating commission interrogated some 580 suspects over a period of five months in the Winter Palace and the Hermitage. Ivan Yakushkin, who was active in the uprising in the Moscow garrison, describes in his memoirs being ‘led into one of the rooms on the lower floor of the Winter Palace. There was a soldier with a naked sabre by each door and window. Here I spent the night and the next day. In the evening I was taken upstairs and to my extreme surprise I found myself in the Hermitage.’ He had been taken to a large room overlooking the Neva, where the Leonardos are now exhibited but which then displayed lesser Italian paintings. Nicholas and General Levashev were seated at a folding table, under a portrait of Pope Clement IX, questioning a succession of Decembrists. ‘It was quite easy being questioned by Levashev and during the whole interrogation I admired Domenichino’s Holy Family,’ Yakushkin wrote.

Nicholas was to keep a summary report of the Decembrists’ criticisms on his desk for the rest of his life, regarding it as a fundamentally important description of the problems of his empire. And, in order to prevent a repetition of trouble, he instituted a secret service, known as ‘the Third Section of His Majesty’s Own Chancellery’, to spy on his subjects. Secret denunciations were encouraged and the department expanded and flourished on the basis of fictitious, or semi-fictitious, plots uncovered by ambitious employees. Russia became, in effect, a police state and the seeds of the Bolshevik Revolution were sown. The same fear of insurrection dictated Nicholas’s foreign policy. He allied himself with the conservative rulers of Austria and Prussia, and regarded France, with its history of revolution, and Britain, with its taste for democracy, as dangerously subversive. He became known as ‘the gendarme of Europe’.

Queen Victoria of England gave a perceptive reading of Nicholas’s character in a letter she wrote to her uncle Leopold, King of Belgium, after the tsar visited England in 1844:

He is stern and severe – with fixed principles of duty which nothing on earth will make him change; very clever I do not think him, and his mind is an uncivilised one; his education has been neglected; politics and military concerns are the only things he takes great interest in; the arts and all softer occupations he is insensible to, but he is sincere, I am certain, sincere even in his most despotic acts, from a sense that that is the only way to govern.

The Queen clearly failed to discover artistic leanings under Nicholas’s stern exterior. She described him as ‘a very striking man; still very handsome; his profile is beautiful and his manners most dignified and graceful; extremely civil – quite alarmingly so, as he is full of attentions and politenesses…. He seldom smiles and when he does the expression is not a happy one.’

Nicholas’s upbringing had reflected his father’s military tastes. On the day after his own accession Paul appointed the four-month-old Nicholas to his first command as Colonel of the Imperial Horse Guards. Nicholas wore his colonel’s uniform at his brother Mikhail’s christening eighteen months later – he was only two. When he was four his father appointed Count Matvey Lamsdorf as governor of his two youngest sons, a man who had no intellectual accomplishments but had pleased Paul while Governor of Courland and director of the First Cadet Corps.

With so much of his education taken up with military matters, it is not surprising that Nicholas followed his brother Alexander’s campaigns against Napoleon with vivid interest, burning to be allowed to play a part himself. At the beginning of 1814, Alexander permitted his two youngest brothers, Nicholas and Mikhail, to join the army in the field – Nicholas was just short of eighteen. ‘I cannot even begin to describe our happiness or, more accurately, our mad joy,’ he later wrote. ‘We began to live and, in a single moment, crossed the threshold from childhood into the world, into life.’

On their way home from the wars in 1815 the brothers visited Berlin where Nicholas fell in love with Princess Charlotte, the daughter of Friedrich Wilhelm III, King of Prussia. For the first, and only, time in his life he took to writing poetry. The young couple wandered happily around the Potsdam countryside and Nicholas proposed on the famous Pfaueninsel, or Peacock Island, a marvellous garden with a fake Gothic castle in the middle of Lake Havel. It was a rare royal love match and their affection never dimmed. ‘Happiness, joy and repose – that is what I seek and find in my old Mouffy,’ he wrote in later life. He was not above having affairs with other women, however, most notably Pushkin’s wife. According to some accounts, the young Frenchman Georges d’Anthès, who killed the poet in a duel over her honour in 1837, had, in fact, been covering up for the Emperor.

Nicholas and Princess Charlotte became formally engaged in October 1815 but did not marry until July 1817 – after Nicholas had made an eight-month tour of Europe at Alexander’s behest, spending four months in England to learn at first hand the unspeakable dangers of democracy. Like the other German princesses who married into the imperial family, Charlotte converted to the Russian Orthodox religion and changed her name in the process, becoming known as Alexandra Fedorovna. Her taste, formed in the artistic milieu of early nineteenthcentury Berlin, profoundly influenced Nicholas. German painters flocked to his court, a German architect built the New Hermitage, and he made an extensive collection of contemporary German sculpture – white marble gods and goddesses by followers of the Danish sculptor Bertel Thorwaldsen and the Italian, Antonio Canova.

The couple started their married life in the Anichkov Palace on Nevsky Prospect which had been built by the Empress Elizabeth in the 1740s for one of her lovers but which had been extensively and frequently altered over the years. They moved into the Winter Palace when Nicholas became Emperor and their alterations of the interior began with the completion of the 1812 Gallery initiated by Alexander. Its formal opening took place in 1826 and they subsequently added portraits by Krüger, the Berlin court painter. Nicholas himself lived and worked in a ground-floor room facing the Admiralty whose spartan furnishings became so famous – he slept on an iron campaign bed – that the room was preserved intact, as a memorial, up to the time of the Revolution. He wanted his wife to be housed in splendour, however, and commissioned Alexander Bryullov to redesign her suite of rooms on the first floor. His chef-d’œuvre was the Malachite Room, where the mix of bright green malachite pillars with gilded plaster work and mirrors still makes a gloriously rich effect.

Meanwhile the French architect Auguste Montferrand rebuilt the Field Marshal’s Hall, one of the largest state rooms, and constructed a throne room beside it as a memorial to Peter the Great. It is still furnished according to Montferrand’s designs, with a portrait of Peter the Great hanging behind a giltwood replica of the massive silver-gilt throne that the Empress Anna Ivanovna ordered from London, the walls hung with red brocade embroidered with silver thread and, below, silver side tables and candelabras that Nicholas’s mother had ordered – and perhaps designed? – for the throne room in the Mikhail Castle. Montferrand, who was trained as a miniature painter, not an architect, had arrived in St Petersburg from Paris, seeking his fortune. He wheedled his way into Nicholas’s good graces by presenting him with a small volume of exquisite architectural views. The great fire of 1837 is generally blamed on his lack of architectural training.

Nicholas and Alexandra Fedorovna were at the Bolshoy Theatre attending a performance of the ballet Dieu et la Bayadère when news of the fire was brought. It had started in a chimney hidden in the wall between the Field Marshal’s Hall and the Throne Room – Montferrand is thought to have left inflammable pieces of wood irresponsibly close to this large chimney connecting the apothecary’s stove on the ground floor, and several subsidiary fireplaces, with the roof. Without telling his wife what was happening, Nicholas hurried home to inspect the fire which took hold relatively slowly – all the portraits in the nearby 1812 Gallery were successfully saved. Nicholas had his young sons taken to the Anichkov Palace and then took command of a massive evacuation of paintings and furniture.

Everything was first dumped in the snow in Palace Square – one of the Empress’s favourite gold ornaments was only found when the snow melted in the spring. Sailors carried out the contents of the vast silver stores. The palace guards threw themselves into the burning building with such enthusiasm that Nicholas was eventually forced to restrain them. He is reputed to have found a crowd of guards wrestling with a firmly fixed wall mirror and, when they ignored his command to leave, to have thrown his opera glasses and shattered it. ‘You see, lads,’ he then told them, ‘your lives are dearer to me than the mirror and I now ask you to leave the building.’ The poet Vasily Zhukovsky described the scene as ‘a vast bonfire with flames reaching the sky’. The fire burned for several days and the Winter Palace was completely gutted.

The reconstruction was completed within eighteen months where it had taken Rastrelli eight years (1754–62) to build the original edifice. This Herculean task was achieved through the massive recruitment of manpower and disregard for human life which is so characteristic of Russia’s great endeavours. Some 8,000 building workers camped in the snow. According to the highly coloured account of Edward Jerrmann, writing in the 1840s:

the work went on literally day and night; there was no pause for meals; the gangs of workmen relieved each other. Festivals were unheeded; the seasons themselves were overcome. To accelerate the work, the building was kept, the winter through, artificially heated to the excessive temperature of 24 to 26 degrees Réaumur. Many workmen sank under the heat, and were carried out dead or dying; a painter, who was decorating a ceiling fell from his ladder struck with apoplexy. Neither money, health, nor life, was spared.

The work was directed by the distinguished Neoclassical architect, Vasily Stasov, but, on Nicholas’s instructions, the main state rooms and staircases were restored as they had been before the fire. Thus Rastrelli’s Jordan Staircase – so called on account of the annual ceremony of blessing the waters of the Neva as a celebration of Christ’s baptism in the River Jordan – was reconstructed from his original plans, complete with its exuberant Baroque plasterwork. Stasov replaced the gilt bronze handrails with white marble and the pink columns with polished grey granite, but otherwise there was little change. He followed Rossi’s designs for the 1812 Gallery, Rastrelli’s for the cathedral and Montferrand’s for the Small Throne Room. He got Alexander Bryullov to redesign the rooms facing Palace Square, however, incorporating, on Nicholas’s instructions, military themes in the grisaille ceiling paintings and plasterwork arms and armour in the new Alexander Hall named after Nicholas’s brother.

During 1838, the year of intensive reconstruction work on the Winter Palace, Nicholas paid a visit to Munich where Ludwig I of Bavaria was in the midst of a major building programme. The connoisseur king, who had come to the throne, like Nicholas, in 1825, was determined to turn Munich into the greatest art centre in northern Europe. He was tearing down the city and raising majestic new public buildings, mostly designed by Leo von Klenze. At the time of Nicholas’s visit Klenze had completed the Glyptothek, a temple-style budding constructed to house Ludwig’s codection of Classical sculpture, and the Alte Pinakothek, or picture gallery, designed in the new ‘Renaissance’ style inspired by the old palazzi of Florence.

Nicholas, with his mind already bent on building problems, was excited and impressed. He was shown round by Klenze and immediately invited him to St Petersburg to design new buildings for the Russian capital. In the event, Klenze only designed one building, but a very grand one – the New Hermitage, a custom-built museum tucked on to the back of Catherine’s Old Hermitage. The idea of constructing a museum where the imperial collection could be displayed to the public was, no doubt, encouraged by Nicholas’s seeing the splendid new galleries that Ludwig had built for his own and his family’s collection.

Klenze had been trained in Berlin and Paris, where he developed his special interest in the ornamental detail of interiors. He started out as a Neoclassicist, basing his early designs on Greek temples, but later adopted a neo-Renaissance style. By the time he designed the New Hermitage he was a thoroughgoing eclectic, and incorporated elements of Greek, Roman, Renaissance, Baroque and Gothic styles, skilfully combining them to achieve a very grand and ornamental effect. The New Hermitage was not merely to be a museum but the museum extension of an imperial palace, and that is what Klenze made it look like.

Klenze’s first design involved pulling down the Small Hermitage and creating a square between the Winter Palace and the proposed New Hermitage. This was turned down and he had to have his building’s main façade looking on to Millionnaya Street, which runs parallel to the Neva at the back of the Winter Palace and leads into Palace Square. The public entrance he designed was spectacular. The Greek-style portico is supported by ten, five-metre granite giants, known by the French term ‘Atlantes’, carved by the Russian sculptor Alexander Terebenev. According to classical myth Atlante, or Atlas as he is known in English, supported the heavens and the Hermitage statues put the same effort into supporting the roof of the entrance.

Klenze was much too busy in Munich to stay in St Petersburg to superintend work on his building, so Vasily Stasov, who had so ably overseen the reconstruction of the Winter Palace, was put in charge of a building commission which directed the work. This commission modified Klenze’s designs and introduced ideas of their own, especially in the interiors. Klenze had designed new furniture for all the galleries but not much of it was made – there are still some of his extraordinary obelisk-shaped showcases in the Antique galleries. Nicholas ordained that furniture from the imperial store in the Tauride Palace should mainly be used. There were some handsome suites of furniture which had been designed for the Winter Palace by Rossi and Montferrand before the fire and not reused afterwards, and they were brought into the museum. The marvellous mahogany chairs, richly embellished with giltwood carving, that Rossi designed in 1818–20 to furnish the guest rooms used by Wilhelm Friedrich of Prussia are still in the museum galleries.

Nicholas and Alexandra were so delighted with the museum that one of the first-floor galleries, now the Michelangelo room, was converted into a rest room where the Empress could happily while away the afternoon. The finest objets de vertu and the Scythian gold were displayed there in Klenze’s obelisk-shaped showcases and Nicholas ordered a new suite of sofas and easy chairs for the Empress from St Petersburg’s leading cabinetmaker Peter Gambs. The gallery seems to have been returned to the museum after Nicholas’s death but when Florian Gilles, the librarian, wrote an account of the Hermitage in the 1860s it was still known as ‘the Empress’s cabinet’ and contained jewels and gold.

One of Nicholas’s happiest ideas for the museum’s decoration was the extensive use of monumental vases carved from the richly coloured hardstones of Siberia. While decorative items were carved from hardstones all over Europe, the scale and sophistication of Russian vases are unique. Most of the finest ones are in the Hermitage, since the three main factories worked almost exclusively for the imperial household. Leading architects designed the vases as well as their intricate ormolu mounts – they generally echo the French Empire style but the Russians added an extra richness.

The first hardstone factory had been established at Peterhof by Peter the Great in 1721 as part of his efforts to introduce European decorative arts to Russia but it was during Catherine’s reign that the great deposits of coloured stone were discovered – the first jaspers in 1765, green breccia in 1780, rhodonite, marble and further jaspers in 1781–3, amazone-stone in 1784, lazurite in 1785, and a deposit of violet, red and black porphyries in the Altai mountains in 1786. Initially the stones were rough-cut on site, and shipped to Peterhof for finishing. However, it was obviously more economic to work where the stone was found and new factories were established at Ekaterinburg, in the Urals, and in the small village of Kolyvan in the Altai. Most of the very large vases came from the latter and had to be transported to St Petersburg over a distance of some 3,000 miles.

The carving of a single vase often took between ten and twenty years. First the stone would be found and its measurements sent to the Imperial Cabinet. The Cabinet would commission a design from an architect, sometimes one of the famous architects who were at work on the imperial palaces, such as Quarenghi, Rossi or Andrey Voronikhin, but more often, in Nicholas’s day, the design was supplied by Ivan Galberg, the official architect attached to the Cabinet. The design was sent back to Ekaterinburg or Kolyvan where the vase was carved and shipped to St Petersburg. It went into the ‘Cabinet Store of Stone Objects’ in the Anichkov Palace and the ormolu mounts would be added.

Every Christmas and Easter an exhibition of the new vases was arranged on the Jordan staircase and the Emperor himself picked out the pieces he wanted for the Winter Palace or the Hermitage. The rejected vases would be used as diplomatic gifts – there is a particularly fine one at Windsor Castle – or just sent back to languish in store. The most famous of all the items Nicholas installed in the New Hermitage is the vast ‘Kolyvan vase’ – its elliptical bowl is five metres long and three metres wide – and its history perfectly illustrates the labour involved in creating these ornamental pieces. The jasper came from Revnevskaya, high in the mountains above Kolyvan – jasper was first found there in 1789. Workers would live in huts at the quarry during summer and rough-cut the stones they found, then slide them down to Kolyvan after the first snows had fallen.

The vast stone from which this vase was cut was unearthed in 1819. The dimensions were sent to St Petersburg and a design, incorporating elaborate carved mouldings on the underside, was supplied by the architect Abram Melnikov. The Cabinet approved his design in 1824 but it turned out not to be realisable; Kolyvan pointed out the difficulties and asked for a plaster model from which to carve. At this point the stone was still at the quarry and the rough-cut, on which up to forty men were working at any one time, was not completed until 1831. Then came the problem of moving the stone over twenty miles of mountain back to Kolyvan – its transport is said to have involved between 500 and 1,000 men.

Work started on the vase at the Kolyvan factory in December 1831 and took eleven-and-a-half years at a cost of 30,284.43 silver roubles. In 1843 it took 154 horses to drag the completed vase to the port at Barnaul where it was put on a ship for St Petersburg. The transport to Barnaul had to be done during winter to avoid using bridges which might have collapsed under the weight of the vase; instead it was taken across the ice. When it arrived in the capital the vase was found to be too large to be moved into the marble store in the Anichkov Palace so a special hut was built for it under the palace colonnade. It stayed there until 1850 or so when it was moved to the New Hermitage whose walls were literally built around it. It has a gallery to itself among the rooms of Greek and Roman antiquities on the ground floor.

The display of antiquities was the most important innovation in the New Hermitage, inspired by Nicholas’s visit to Munich and the great impression that Ludwig’s Glyptothek had made on him. Catherine the Great had established the Hermitage picture gallery and allowed visitors to admire it but the imperial collection of Classical antiquities had never been gathered together or put on show. Antique sculptures, vases and jewellery had been acquired from the time of Peter the Great onwards and some gold items were exhibited in Peter’s Kunstkammer. However, sculptures had habitually been used as decoration and were spread around the imperial palaces and their parks, or stored in various palace basements. Nicholas gathered the best together in order to establish his new galleries. As today, the ground floor of the New Hermitage was devoted to antiquities and the upper floor to pictures.

The most exciting and original feature of the display of antiquities, then as now, was the range of gold and silver artefacts, some exquisitely wrought, that had been found in Scythian tombs in southern Russia. The Scythians, a nomadic people who originated in Central Asia, arrived in the Black Sea area in the eighth century BC and remained politically dominant there for the next 400 years. They became immensely wealthy through trading corn, grown on the fertile plain to the north of the Black Sea, with the Mediterranean world. Their princes went to their graves decked out with rich gold ornaments. Mostly these were made by Greek craftsmen, who were the most sophisticated jewellers of the ancient world. The Scythians either imported their gold jewellery from Greece or commissioned Greek craftsmen who had settled locally to make it for them – Greek colonies were established in the Crimea and along the north coast of the Black Sea from the seventh century BC onwards.

At the time the New Hermitage was being built, Russian archaeology was still in its infancy. The Academy of Science, founded in 1725, had sent expeditions to Siberia in the eighteenth century but they were essentially treasure hunters. The tall burial mounds that remain one of the curiosities of the south Russian landscape only began to attract attention at the end of the eighteenth century. The first purposeful excavations were made on the orders of the Russian military governors – the territory had only been acquired by Russia during Catherine’s reign and the governors were busily building roads and towns. A burial mound at Litoi was opened by General Melgunov, another at Taman by General Vandervelde, mounds near Kerch by General Gangeblov while General Suchtelen began to excavate the ancient city of Olbia.

There was also a most influential influx of French émigrés who had been ousted from France by the Revolution. The most notable was Paul Dubrux who spent three years in the Russian army from 1797 to 1800, and then became a Commissioner of Health in the Crimea. He began to excavate on his own account in 1816 and spent all his free time exploring and mapping ancient remains – he received a small subsidy from Count Nikolay Rumyantsev, chancellor of the empire, and gave some of his early finds to the Dowager Empress Maria Fedorovna, Nicholas’s mother. Thus home-grown archaeology began to attract the attention of the court. New museums were established in Kerch and Odessa in 1823 to house local finds and it was ordered that the finest pieces should always be sent to the Hermitage. The Hermitage collection is thus extraordinarily well documented – most other museum collections of antiquities were bought from dealers who rarely knew, or wished to reveal, the exact location and date at which pieces had been found.

In 1830 came the sensational opening of the burial mound at Kul-Oba, close to Kerch, which stirred the imaginations of the intelligentsia and nobility throughout Russia. The Governor of Kerch, Colonel Ivan Stempkovsky, was a keen amateur archaeologist and on 19 September 1830 he invited his friend Paul Dubrux to come and watch 200 soldiers who were removing stones from two burial mounds to build a barracks. Dubrux realised from the shape of the stone structure that was revealed that the site contained an unexplored tomb.

It turned out to contain a Scythian king of the fourth century BC who had been buried with his wife and servant. Around his neck he wore a magnificent gold torque ending in figures of Scythian horsemen; beside him lay a gold libation bowl, its lobes embossed with twelve gorgons’ heads, twelve panthers, twenty-four bearded heads of deities, forty-eight boars’ heads and ninety-six bees. His wife wore an elaborate gold pendant embossed with the head of Athene, copied from the famous statue of the goddess by Phidias in the Parthenon. At her feet was a five- inch gold flask worked by a Greek master with scenes from life – two seated warriors chatting, a man stringing a bow, a man treating another’s mouth ailment and another bandaging his friend’s wounded leg. They all wear patterned trousers and belted tunics, in contrast to the naked, or lightly draped, heroes of native, Greek imagery. The vase is one of the highlights of the Hermitage collection of Scythian gold.

It has been suggested that the scenes around its sides illustrate the Greek myth concerning the founding of the Scythian kingdom, as reported by Herodotus, the fifth-century BC historian. Herodotus writes that ‘the Greeks who dwell about the Pontus’ say that ‘Heracles, when he was carrying off the cows of Geryon … being overtaken by storm and frost, drew his lion’s skin about him, and fell fast asleep. While he slept, his mares, which he had loosed from his chariot to graze, by some wonderful chance disappeared.’ They had been taken by ‘a strange being, between a maiden and a serpent, whose form from the buttocks upwards was like that of a woman while all below was like a snake’ and she would not give them back before he had intercourse with her.

The result was triplets and before Heracles left her, the snake lady enquired: ‘When your sons grow up, what must I do with them?’ Heracles replied: ‘When the lads have grown to manhood, do thus, and assuredly you will not err. Watch them, and when you see one of them bend this bow as I now bend it, and gird himself with this girdle thus, choose him to remain in the land. Those who fail in the trial send away.’

In a book on the Scythians published in 1977, D. S. Raevsky suggests that the scenes on the queen’s little vase depict the three brothers attempting to string Heracles’ bow. Two have failed and hurt themselves in a manner common when stringing a bow, one on the jaw and the other on the calf of his leg, which is being bandaged. Meanwhile the youngest son, Scythes, who was to inherit the kingdom, is quietly and successfully, attaching the bow string.

The so-called ‘Kerch Room’ was one of the most popular highlights of the New Hermitage when it opened to the public in 1852. It had been artistically arranged with gold objects, bronzes, vases, terracottas and stone sculptures from the burial mounds of southern Russia. The excavated jewellery was upstairs in Alexandra’s rest room – there were eighteen crowns, four diadems and a gold death mask. In all, almost 1,500 objects from Kerch were put on show.

From the very start the antiquities galleries were thus of a high standard, suitably matching the extraordinary riches of the paintings collection which Nicholas had inherited. He took the same close personal interest in the preparation of the picture galleries but, in this case, to a less happy effect. He began by setting up a commission of three artists to review all the paintings in the imperial collection and divide them into four classes: those worthy of display in the new galleries (815), those suitable to be used as decoration elsewhere in the imperial palaces (804), those that should be kept in store (1,369) and those of no importance (1,564). The keeper of the picture gallery, Fedor Bruni, tells us in his memoirs that the Emperor would visit the museum from 1 to 2 p.m. every day to supervise the work of the commission. ‘If he had once defined a painting as a work of this or that school, it was no easy matter to make him change his opinion,’ Bruni writes and quotes a typical exchange between the two of them: ‘This is Flemish,’ Nicholas pronounced. ‘But it seems to me, Your Majesty …’, ‘No, Bruni. Don’t argue. Flemish it is.’

Nicholas had the pictures in the last category – those condemned as of ‘no importance’ – sent to the Tauride Palace where he picked out a few as suitable gifts and ordered that the rest should be auctioned off. Naturally enough, the commission of painters, under the eccentric direction of Nicholas himself, had missed many pearls. An astute art dealer, A. A. Kaufmann, acquired the wings of a Lucas van Leyden triptych for thirty roubles and sold them back to the Hermitage in 1885 for 8,000 roubles. Other paintings which returned to the Hermitage as a result of confiscations and sales after the Revolution are Chardin’s Still Life with Attributes of the Arts in 1926, Charles-Joseph Natoire’s Cupid Sharpening an Arrow in 1932, and Pieter Lastman’s Abraham on the Road to Canaan in 1938. Others got away for good, including a José de Ribera now in the National Gallery, Warsaw, a Kneller now in the National Gallery, London, and a Terborch in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Nicholas’s own acquisitions were heavily influenced by Alexandra Fedorovna and the taste of the Berlin court. Her father was an enlightened patron of Berlin’s Biedermeier artists whose particular strengths lay in portraiture, architectural views and pictures of military parades. One of Franz Krüger’s greatest masterpieces, Parade on the Obernplatz, Berlin, in the Year 1824, now in the Berlin National Gallery, was commissioned by Nicholas I – it was given to Kaiser Bill by Nicholas II in 1912. It depicts the Brandenburg cuirassiers whose command Nicholas I had been given by his father-in-law. The Hermitage still owns twenty portraits by Krüger. Another Berlin master, Eduard Gärtner, a specialist in architectural views and genre, was commissioned to supply a replica of the masterpiece he painted for Alexandra Fedorovna’s father, Panorama from the Roof of the Friedrichswer- derkirche, a 360-degree view of Berlin, made up of six separate panels; the replica is now in the Palace at Peterhof. Gärtner came to St Petersburg in 1837 and was commissioned to paint interior and exterior views of imperial palaces.

Watercolours depicting the interiors of houses and castles became very popular in Berlin in the Biedermeier period and Gärtner was one of the pioneers of the genre. Alexandra’s sister Louise had commissioned paintings of her favourite rooms in the Berliner Schloss from him as early as 1821 and the fashion now spread to Russia. Nicholas commissioned watercolours of palace interiors from many different artists and, after the New Hermitage museum was completed in 1852, commissioned a special series to record its elegant arrangements from Eduard Hau, Konstantin Ukhtomsky and Luigi Premazzi. His son, Alexander II, followed up by ordering a major series of watercolours recording the appearance of the rooms in the Winter Palace. They are still in the Hermitage and, together, make up a fascinating portrait of gracious, imperial living in the mid-nineteenth century.

The biggest catch from Germany, however, was Caspar David Friedrich, now regarded as the most important German painter of the Romantic movement. His landscapes, with their lonely figures, twisted trees, ruins and dramatic effects of light, were a transcription of his religious beliefs; he saw God in nature, which gives his paintings a powerful spiritual impact. The Hermitage has nine paintings and six drawings, all specially commissioned or carefully selected from his studio. Nicholas bought the first of them, On Board a Sailing Ship, on a visit to Friedrich’s studio in 1820, presumably at the behest of Alexandra Fedorovna whose father and brother were already Friedrich’s patrons. The connection was fostered by the poet Vasily Zhukovsky, who was first employed to teach Alexandra Fedorovna Russian and subsequently became Alexander II’s tutor and mentor. He visited Friedrich in 1821 at Alexandra Fedorovna’s suggestion and became a lifelong friend of the artist.

By marrying into the Prussian royal family, Nicholas allied himself with the very source of his father’s and grandfather’s militarism – it was the parades, uniforms and manoeuvres of Frederick the Great’s armies which both had endeavoured to emulate in Russia. Alexandra Fedorovna had also inherited this taste. Writing of the day she first arrived in St Petersburg, the homesick princess recorded: ‘I was delighted to see again the Semenovsky, Ismailovsky and Preobrazhensky Regiments which I remembered from a military review in Silesia … during the armistice of 1813. And when I saw the Chevalier Guards drawn up near the Admiralty, I could not restrain a small cry of pleasure because they reminded me of my beloved Guards of the Berlin Regiment.’ The couple’s fascination with military matters is reflected in two collections – that of arms and armour which ended up the most extensive and important in Europe and is still in the Hermitage, and that of paintings of military subjects, most of which were either consigned to storage or actually got rid of after the 1917 Revolution. Nicholas’s passion for such paintings verged on mania.

The Alexander Nevsky sarcophagus, commissioned by the Empress Elizabeth and designed by the court painter, Georg Christoph Grot. It is made from sheet silver over a wooden carcass and stands 16 ft high.

Scythian gold comb of the early fourth century BC, excavated in the Dnieper valley in 1913.

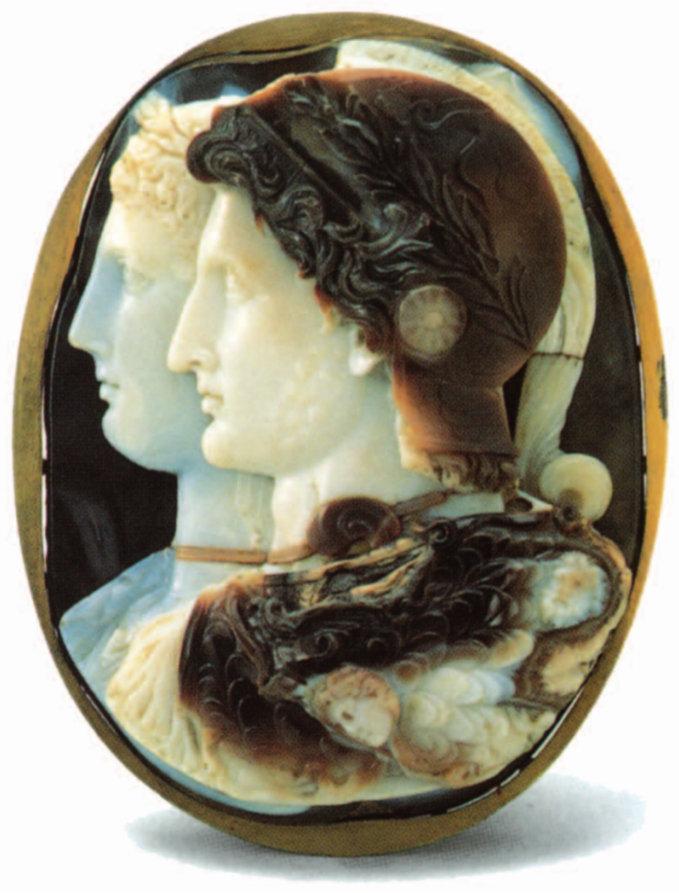

The so-called ‘Gonzaga cameo’, carved from sardonyx in the third century BC and believed to depict King Ptolemy II of Egypt and his wife Arsinoe.

The Transfiguration, a twelfth century icon painting acquired from Mount Athos through Petr Sevastyanov in 1860.

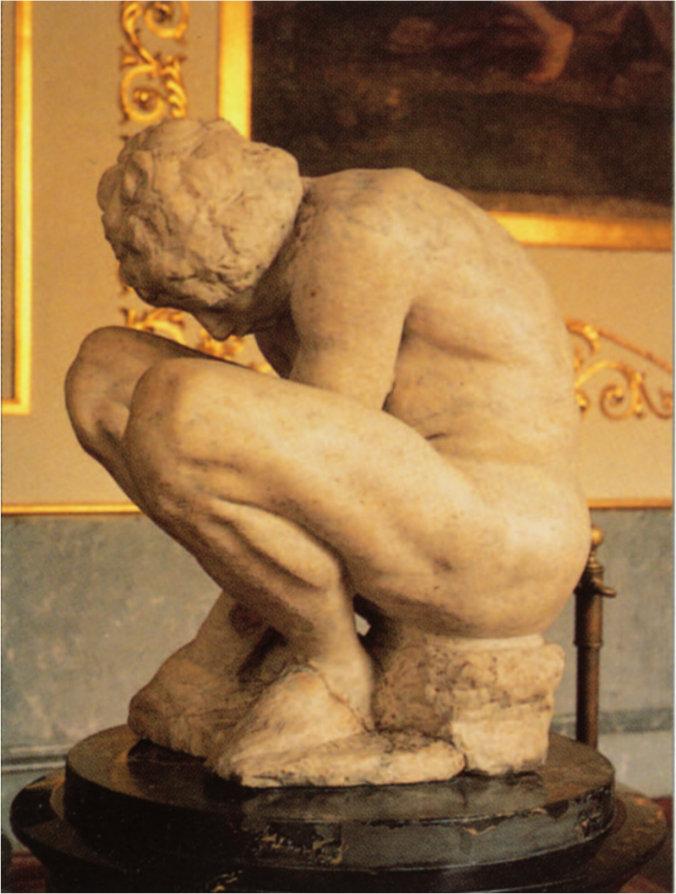

Michelangelo’s unfished Crouching Boy, dated 1530–34, acquired with the Lyde-Brown collection in 1787.

A life-size, marble statue of Voltaire, commissioned by Catherine the Great from Jean-Antoine Houdon in 1780, banished from the palace by Nicholas I with the memorable words ‘destroy this old monkey’.

The Kiss by Jean-Honoré Fragonard from the collection of Catherine the Great’s lover, Stanislaw Poniatowsky.

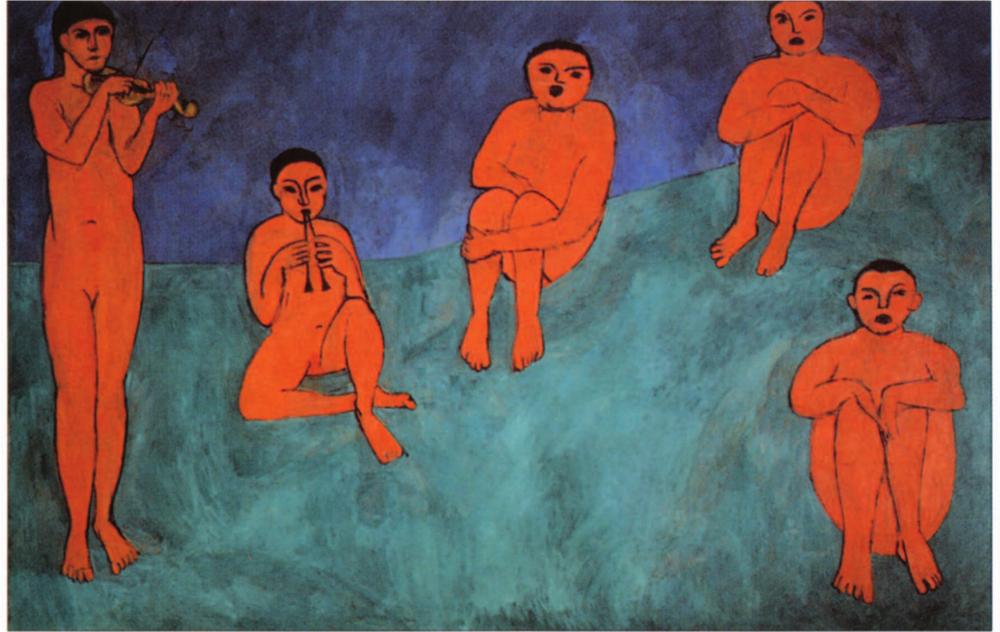

Music, one of a pair of monumental paintings by Henri Matisse commissioned by Sergey Shchukin for the stairwell of his Moscow home. Shchukin got cold feet about the nudity of the figures and painted out the flautist’s private parts.

The catalogue of his private collection, made after his death, included 666 paintings, of which 650 were military scenes. In his idle days at the Anichkov Palace, before he became Emperor, he not only tried his hand at making military paintings himself, but also painted figures of soldiers into the Old Master landscapes hanging on his walls. One entry in his catalogue reads: ‘Van Goyen: Landscape with the manoeuvre of Russian troops. Figures painted in by His Imperial Majesty when Crown Prince.’ Jan van Goyen was a seventeenth-century Dutch landscapist, a masterly interpreter of the flat fields, waterways and windmills of Holland set off by low horizons and big skies – a landscape where Russian troops never penetrated except in the imagination of Nicholas himself.

After the 1837 fire in the Winter Palace imposed on him a duty to rebuild and redecorate, Nicholas conceived the idea of a ‘War Gallery’, to be composed of paintings depicting the most famous battles of Russian history. In the wake of the Napoleonic wars, battle painting had become a popular genre throughout Europe and Nicholas was inspired by the example of the Galerie des Batailles at Versailles – which opened in 1836 – and the Schlachtensaal in the royal palace at Munich, the Residenz. Peter Hess of Munich supplied the principal masterpieces of the War Gallery. He painted with almost photographic realism, lovingly delineating smoking cannon, bloodstained bandages, dying horses and staggering soldiers, all in the correct uniforms – he had accompanied the Bavarian army in campaigns against Napoleon in his youth. He was invited to St Petersburg by Nicholas in 1839 and spent the next thirteen years of his life on a series of eight large paintings and four smaller ones depicting famous Russian engagements with Napoleon’s army. He visited the battlefields and took the most painstaking care to achieve absolute ‘realism’ – copies of twenty generals’ portraits from the 1812 Gallery were sent to Munich for him to work from.

He had, however, met his match in his imperial patron. Nicholas’s criticism of the first canvas Hess sent from Munich, The Battle of Vyazma, did not dwell on aesthetics: 1. The officers’ coats in the picture are buttoned down the left front; our officers all button theirs down the right front. 2. The cloak of a non-commissioned officer should not be trimmed with galloon. 3. No white edging to the cravat….’ Once these important matters had been seen to, the paintings were received with overwhelming enthusiasm in Russia. Many copies were made for the administrative offices of towns near the battlefields and other interested institutions. Several of the paintings were reproduced as complete books – the detail in Hess’s panoramas made this kind of treatment possible. But today only two of them are on view, Crossing the Berezina River and The Battle of Borodino. They were added to the display in the 1812 Gallery after World War II.

Nicholas also decorated a suite of five rooms overlooking Palace Square with battle paintings. The rooms are now filled with masterpieces of the French eighteenth century. The ceilings painted in grisaille with guns, banners and other military motifs, provide a gentle echo of past times. Most of the paintings were sold off by the Soviet government in the 1920s and 1930s.

Nicholas’s collection of arms and armour, or Arsenal, was undertaken in a similar, romantic spirit but to much more interesting effect. In his introduction to the magnificent catalogue of the collection produced between 1835 and 1853, its keeper Florian Gilles highlights Nicholas’s debt to historical novels. ‘Thanks to Walter Scott and some other famous writers, the study and classification of fifteenth, sixteenth and seventeenth century arms came into favour,’ he says. Historical novels were, indeed, central to the early nineteenth-century Romantic movement – Scott and his ilk brought chivalry and its trappings into fashion. Nicholas was interested in all the trappings. In addition to weapons of war, he bought wonderful carved ivory hunting horns, wriggling with deer, wild boar and rabbits amidst rich foliage, as well as medieval stained glass and metalwork.

As a child, Nicholas knew and admired the collection of arms his father had at Gatchina, his country palace near St Petersburg, and it was probably a desire to emulate his father that started him collecting. The Gatchina arsenal had, in fact, been begun by the first owner of the palace, Count Grigory Orlov, Catherine the Great’s lover. She had ordered hunting equipment for Orlov from the leading European armourers in the late eighteenth century on an exceptionally lavish scale, since Orlov liked large hunting parties. Nicholas made his first acquisition at the age of thirteen when General Lageron gave him a Turkish sabre taken by him in the 1811 campaign against the Turks; arms captured in war were always a useful source for imperial collectors.

Nicholas, however, collected in the spirit of the new century. He did not buy arms either for decoration or for use but in the scientific spirit of an antiquary. He wanted the best makers of East and West to be represented in his collection and the history of arms manufacture to be illustrated by his pieces, with all its by-ways and cul de sacs. The collection includes, for instance, an interesting group of medieval torture instruments as well as superb Mannerist helmets from Milan, Russian hatchets, their blades patterned with inlaid gold, and jewelled Indian daggers. His collection contains 6,000 European arms, 2,000 items of Russian manufacture and another 7,000 or so pieces from the Orient, principally Turkey, Persia and India, a reminder that Russia is as much an Oriental as a European country.

Once he had become emperor, Nicholas moved his collection of arms and armour into a fake medieval castle that his brother Alexander had built in the park of his country palace at Tsarskoe Selo – a little jewel, faced in pink plaster, with four towers and a crenellated parapet. In Nicholas’s time it could be lived in. There was a bedroom, dining room, study and library. The latter, according to Florian Gilles, contained a ‘small but precious’ collection of works on chivalry, heraldry and the Middle Ages.

Gilles explains that the collection was guarded by a group of twenty retired officers from the Imperial Guard – ‘old soldiers covered in wounds from many different fields of battle … who happily remember, as they clean the arms, their own glorious careers. They often have the pleasure of seeing their Sovereign who loves to visit his arsenal and on such occasions is not above chatting familiarly with these brave old men.’

By the time the Arsenal was moved from Tsarskoe Selo to the Hermitage in 1885 it also contained a group of Colt pistols from America, which latter-day collectors make pilgrimages to St Petersburg to see. Samuel Colt had taken out patents in the 1830s on the multi- chambered rotating breech, which he invented, but it was the Mexican War of 1846–8, and the resulting vast US government orders for his pistols, that led to the mass production of Colts and made his fortune. When the Crimean War broke out in 1854, Colt scented new opportunities. The richly ornamented, presentation pistols he made for Nicholas I, his son Alexander II, and Alexander’s two brothers, the Grand Dukes Konstantin and Mikhail, form a unique series. They are pretty toys, the steel parts blued, embellished with engravings and damascened in gold, the grip mounts sculptural arabesques of gilt bronze. The first two of the series, a five-shot and a six-shot revolver, were presented to Nicholas in 1854.

The Crimean War, which pitted Russia against Turkey, Britain, France and Piedmont, revealed to Nicholas that his precious army was trained and equipped for the parade ground, not for real war. Its equipment was technologically out of date and hurried efforts to bring it up to standard resulted in Colt receiving the bulk orders his presentation pistols were designed to attract. Curiously, despite his fascination with military matters, Nicholas had comparatively little experience of real war.

When he came to the throne in 1825 the defeat of Napoleon was still fresh in every memory and the Russian army was bathed in an aura of glory. In July 1826, just as Nicholas arrived in Moscow for his coronation, the Persian army invaded Russian territory in the Caucasus. After a rather incompetent campaign, the Russian army drove them back and peace was signed in January 1828. Three months later, when the Sultan refused to allow Russian ships to pass through the straits from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean, Nicholas declared war on the Ottoman Empire. This limited war was concluded in August 1829 with the defeat of the Sultan’s forces. Thereafter, the principal role of the Russian army was the suppression of revolt, in Poland in 1830 and Hungary in 1849.

The bitter aftermath of the Polish revolution, which Nicholas regarded as a betrayal, revealed his aptitude for destroying art – presumably an act of ritual revenge. The Hermitage archives contain a report from the chief restorer, Alexander Mitrokhin, to Franz Labensky, keeper of the picture gallery: ‘In fulfilment of Your Excellency’s instructions of this 26 July concerning the destruction, by His Imperial Majesty’s command, of certain portraits, pictures and other things brought from Warsaw in seventeen boxes, we have the honour to report that on this 31 July … the said portraits, pictures and other things have been annihilated and burnt, with the exception of a portrait of the Emperor Alexander I which we intend to rub out with pumice stone.’

Nicholas’s high-handed attitude to art, including, when he deemed it necessary, its destruction or sale, has often led to his being depicted as a philistine. There is no doubt, however, that Nicholas loved the Hermitage museum in a very intimate way. He is said to have paid it a farewell visit a day or two before his death. Broken by the failure of his Crimean campaign, and the ignominious revelation that his cherished army was incompetent in the field, he may have committed suicide. Alexander Herzen, the dissident intellectual, repeatedly claims this in his writings, although official reports stated that Nicholas died of pneumonia after reviewing his troops in the snow. As he wandered through the Hermitage galleries for the last time, he was heard to murmur: ‘Yes. Here is perfection!’