It might be expected that a Communist state would feel bound to desecrate or destroy an elitist collection of art treasures put together by a hated imperial family that had just been overthrown. The very opposite happened in Russia. The Hermitage, from the first days of Soviet rule, was regarded as a precious repository of national culture which should be preserved for the enjoyment of the proletariat. ‘Amongst the broad masses of the population,’ Benois commented, ‘and unexpectedly for many, there was revealed, if not genuine appreciation, then something like awe which saved our treasures.’

Among the avalanche of posters produced in the early days of Bolshevik rule, inciting the citizens to virtuous behaviour in every department of life, there was one which read:

Comrades. The working people are now in full control of the country. The country is poor, financially devastated by the war, but this is only a passing phase, for our country has inexhaustible potential. It has great natural resources, but apart from them the working people have also inherited a huge cultural wealth, buildings of amazing beauty, museums full of rare and marvellous objects, libraries containing great resources of the spirit…. Russian working people, be a careful master! Citizens, preserve our common wealth!

There was, of course, some looting after the Revolution but in the circumstances, surprisingly little. Later, however, the government raided the nation’s stocks of art treasures in order to earn foreign currency to pay for vital technologies and industrial equipment from abroad. There were two waves of selling, the first one in 1920–24, concentrated mainly on gold, silver and precious stones, and the second in 1928–31 which saw the dispersal of several thousand items from the Hermitage, including some of the greatest masterpieces of the paintings collection. On top of this the Hermitage was expected to supply the new Pushkin Museum in Moscow with a ready-made collection and the new republics began demanding the return of their heritage – the Ukraine alone prised tens of thousands of pieces out of the old imperial museum. The 1921 peace treaty with Poland after the Civil War theoretically entailed the return of all works of art that had left Poland for Russia since 1772, whether they were in private or public collections.

The outflow of art could be described as a haemorrhage. The museum was compensated by a massive volume of new acquisitions – although nothing quite matched the quality of the paintings sold abroad or given to Moscow. The result was a radical change in the profile of the museum collection. On the one hand, the Hermitage was given all the best art in public and private collections in St Petersburg, and only required to share a little of it with other Russian museums. This resulted in a major accretion of applied arts and the acquisition of some good pictures to compensate for devastating losses. On the other hand, the range of the collection was extended by opening three new departments devoted to Oriental art, Russian art and archaeology. Artefacts recovered from digs hugely swelled the size of the collection. By 1996 the museum owned three million objects compared to one million in 1916. The old, imperial Hermitage had focused almost exclusively on Old Master paintings and Classical antiquities; the new museum was a much larger institution with a broad, almost encyclopaedic, sweep of interests. It became the Soviet government’s number one cultural showcase.

High visibility had its drawbacks. It meant that the museum was repeatedly tossed on waves of political cataclysm. At each stage in the great Communist experiment, life in the museum faithfully mirrored the political evolution of the country. It started with muddle and high ideals, suffered desperate shortages of food and fuel, struggled to cope with a collection hugely extended by nationalisation, was forcibly politicised from 1928–31, then robbed of many staff by groundless arrests and executions during Stalin’s terror. One colourful product of the times was the museum’s very own autocrat, Iosif Orbeli, director from 1934 to 1951, a mini-Stalin, though much less destructive. He was an archaeologist and specialist on the Middle East who had set up the museum’s Oriental Department in the 1920s. Hugely able and hugely ambitious, Orbeli was emotionally unbalanced, often indulging in wild rages, but he also had brilliance and charm which resulted in romantic liaisons with a succession of female curators. He had five official wives but Camilla Trever, the curator of Sassanian and Graeco-Bactrian art – whom he never married – remained his faithful mistress and collaborator throughout his long and distinguished career. She is said to have been very beautiful but was a rather pedestrian scholar.

Some vivid vignettes of the struggles of museum life in the 1920s and early 1930s are provided by the memoirs of a curator of applied art from the Western European Department called Tatiana Tchernavin, who fell foul of the Party and the police and made her escape to the West in 1932. While her account (published in 1933) is anti-Communist to an unbalanced degree, reflecting her own terrible experiences of mental and physical torture, she provides a perspective on the period that no one who remained in Russia would have dared to express. ‘To understand what it meant to work in a museum in the U.S.S.R.,’ she wrote, ‘it must be remembered that on the one hand, the museums were so rich in art treasures and so interesting that it was impossible not to be enthusiastic about the wealth of new material and new avenues of work opening up before one at every step; on the other hand, the Soviet Government, though apparently anxious to preserve them, was really their chief enemy. It was ready at any moment to give away or sell everything they contained and to imprison or exile the curators for the least attempt to resist this.’

Despite the cataclysms that affected the lives of all Russian citizens, the period from 1917 to 1941 saw the establishment of the State Hermitage Museum, as we know it today – a mix of national gallery, museum of applied arts and archaeological museum housed in a series of magnificent palace buildings. On paper, the Winter Palace was handed over to the Hermitage in 1918, although many other institutions moved temporarily into the palace and the museum did not get full use of it until 1958. A new Oriental Department was established in the 1920s, an Education Department in 1925, an Archaeological Department in 1931 and a Department of Russian Culture in 1941 – all of them grafted onto the existing picture gallery, antiquities collection, the Arsenal and Numismatics Departments. The process of change was evolutionary with no sudden breaks, although there were many painful periods for the staff of the museum. From 1917 onwards, the story of the Hermitage becomes, above all, the story of its curators, their trials and their achievements.

Before the Revolution curators were appointed by the Ministry of the Imperial Court which survived, almost untouched, through the six-month reign of the Provisional Government. Besides the Hermitage it ran the imperial theatres, the Archaeological Commission, the Academy of Arts, the former palace orchestras, the Kappelle – a chapel choir school attached to the palace – the stables, the library and the Winter Palace itself. Lunacharsky sent a twenty-two-year-old Bolshevik Commissar, Yury Flakserman, to take over the Ministry. He was initially simply ignored. ‘In the Palace Ministry,’ he later wrote, ‘there was complete order. Everyone came punctually to work and scribbled away as if nothing had happened.’

The keepers were essentially a conservative bunch – the museum’s reluctance to recruit young connoisseurs had been a source of much criticism before the war. Many scholars had come and worked for free – Benois had written a catalogue of the museum without being invited to join the staff. Oskar Waldhauer, the young scholar who had charge of the Classical antiquities, taught at the university during the day and worked at the museum in the evenings.

Waldhauer has gone down in museum history as the first promoter of a populist educational programme; education later became a major part of the museum’s activities, with a department to itself from 1925. Waldhauer organised lectures for school children and workers after the Revolution, having agitated unsuccessfully for them to be introduced before 1917. Count Dimitry Tolstoy’s memoirs, however, paint him in a less saintly light. He was the first person the attendants wanted to sack as they began to flex their muscles after the February revolution. ‘He was still young,’ Tolstoy tells us, ‘a very serious scholar but liable to fire up, and very demanding of servants – which often gave rise to dissatisfaction.’

Tolstoy himself had come to the museum through the ranks of the civil service, at that time a highly structured organisation which employed virtually all the nobility. Born in 1860, he spent several years in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and travelled widely before being recruited in 1901 by Grand Duke Georgy to help run the Russian Museum, of which the Grand Duke was director. Tolstoy was a friend of many artists and art historians and in 1909 became director of the Hermitage, while continuing to act as the Grand Duke’s number two at the Russian Museum. He is regarded as having overseen a renaissance of activity at the Hermitage in the immediate pre-Revolution years.

His deputy was Eduard Lenz, a knowledgeable but old-fashioned figure who had charge of the Medieval Department, which also included the Arsenal. The picture gallery was in the hands of Ernst Liphart, already seventy but of high scholarly distinction. He is reputed to have been a brilliant mimic. Fluent in German, French, English, Italian and Spanish, his imitation of an international congress – which involved him leaving the room and returning in the character of a succession of delegates – was a famous party trick. Among the other important figures were Yakov Smirnov, the expert on Oriental silver, and Sergey Troinitsky, who was in charge of objets de vertu. Troinitsky was a chain smoker with encyclopaedic knowledge and a lively sense of humour, according to the affectionate memory of one of his students.

At the beginning of 1918 the keepers were relatively unemployed. They had a museum building but all the best of their collections were in Moscow and the Hermitage was closed to the public. They went to work on rescuing private collections, making inventories and using their expertise to identify what was of value and what was not. Initially their attention was claimed by the inventorisation of collections that Tolstoy had taken into the museum store for safekeeping, for instance the collection of Countess Sofya Panina, one of the leaders of the Kadet party who was arrested on 11 December as an ‘enemy of the people’. The museum had charge of her Poussins, Claude Lorrains, Boucher, Ribera and Zurbaran. Until 1928 these, and other paintings and works of art from private collections, were listed on separate inventories. Thereafter, those that had not been removed for sale abroad were merged with the museum collection.

Meanwhile Lunacharsky’s Commissariat of Enlightenment was setting up new structures for the administration of the arts from its offices in the former children’s apartments of the Winter Palace. When Lenin moved the seat of government from St Petersburg to Moscow in March 1918, Lunacharsky chose to remain in St Petersburg where so many of his responsibilities were concentrated, pointing out to Lenin that he would need a reliable representative in the old capital. ‘Things will be hard for St Petersburg,’ Lunacharsky predicted. ‘It will have to go through the agonising process of reducing its economic and political significance. Of course, the government will try to ease this painful process, but still Petersburg cannot be saved from a terrible food crisis or further growth of unemployment.’

The two years of civil war did, indeed, bring St Petersburg incredible sufferings. Yury Annenkov, the Constructivist painter and graphic artist who later emigrated to France, recalled: ‘It was an era of endless hungry lines, queues in front of empty “produce distributors”, an epic era of rotten, frozen offal, mouldy bread crusts and inedible substitutes. The French, who had lived through a four-year Nazi occupation, liked to talk of those years as years of hunger and severe shortages. I was in Paris then, too…. No-one died of hunger on icy sidewalks, no-one tore apart fallen horses, no-one ate dogs, or cats, or rats.’ Yakov Smirnov, the keeper who first published the Hermitage’s incomparable collection of Sassanian silver, was among the museum employees who died of hunger.

Meanwhile, March 1918 saw two important innovations. On 25 March the special Commissar, Grigory Yatmanov announced at a General Meeting of the Hermitage staff that the government intended to hand the whole of the Winter Palace over to the museum – a decision which took forty years to implement. On 18 March, Lunacharsky set up a new Collegium for the Preservation of Monuments and Museum Affairs, recruiting Troinitsky and James Schmidt, from the picture department, to serve on the council as representatives of the Hermitage. The Collegium took over the role that Benois and Gorky’s Commission had played under the Provisional Government – Benois and Gorky were also invited to join the board – and added to its portfolio responsibility for Vereshchagin’s Artistic Historical Inventorisation Commission. Having nationalised the imperial collections, the new government urgently wanted to know what was in them.

The process of identifying and listing the nation’s store of art works was extended in the course of 1918 by the nationalisation of great aristocratic collections, which meant further urgent calls on the expertise of the Hermitage staff. Then, on 5 October Lenin signed a decree on ‘the registration, inventorisation and preservation of monuments of art and antiquity owned by private individuals, societies and organisations … with the purpose of preservation, study and the fuller acquaintance of the broad mass of the population with the treasuries of art and antiquity in Russia’. This was a first step in the process of taking all private collections into public ownership; the decree required that they should all be registered and listed. The new law warned that objects could be forcibly alienated from their owners if ‘their preservation is threatened by the carelessness of their owners, or as a result of their owners being unable to take the necessary measures for their preservation or in the case of the owners not observing the rules on their storage’. The formal nationalisation – or confiscation – of all private collections did not come into effect until 1923.

Art and antiques were pouring out of the country in the baggage of emigrating nobles, and Maxim Gorky drew the new government’s attention to this in May 1918. He wrote to Lenin, quoting from the letter of a friend who had been in Stockholm, where he said there were ‘almost sixty antique shops trading in pictures, porcelain, bronze, silver, carpets and other objects of art exported from Russia. In Christiana I saw twelve such shops and there are many more in Göteborg and other towns in Sweden, Norway and Denmark.’

When it was discovered that the Princess Meshcherskaya was negotiating to export her family’s Botticelli tondo, there was a crisis debate in the government’s ruling Council of People’s Deputies. Lunacharsky was told to ‘develop in 3 days an outline of a decree forbidding the export beyond the borders of the RSFSR of pictures and all important artistic valuables’. It was drafted by the Collegium on Museum Affairs, with the help of Troinitsky and Schmidt, and required all shops, commission offices and individuals trading in art, including middlemen and experts, to register with the Collegium. The new regulations were signed into law by Lenin on 19 September 1918.

It was in his role as academic secretary to Lunacharsky’s Collegium on Museum Affairs that Iosif Orbeli, the future director, first began to take an interest in how the Hermitage was run. It is probable that he got the job through the influence of the renowned linguist and archaeologist Nikolay Marr, whose organisational secretary and right-hand man Orbeli had become after graduating from the Oriental faculty of the university. Marr was much esteemed by the revolutionaries. The Archaeological Commission, whose offices were in the New Hermitage building, was converted into the Academy of the History of Material Culture under the directorship of Marr in 1919. When Orbeli attended his first meetings at the Hermitage, he is said to have sat next to Yakov Smirnov who had taught him at the university. Orbeli’s contacts thus conveniently spanned the revolutionary and the conservative.

The body of keepers could not remain unchanged under these new conditions. In June they decided that it would be desirable to strengthen their hand by recruiting influential outsiders to their Council. At a meeting on 18 June they voted to invite three people to join, Mikhail Rostovtsev, an eminent archaeologist and expert on the Scythians (elected unanimously), Alexandre Benois (ten in favour, one against) and Sergey Zhebelev, the Professor of Archaeology at St Petersburg University and a Classical historian (eight in favour, three against). Rostovtsev emigrated a matter of two weeks after his election – and was shortly followed by Tolstoy himself

Peter I, known as Peter the Great (reigned 1682–1725) by Andrei Matveyev

(Wikimedia Commons)

Peter’s wife Catherine I (reigned 1725–27) by Jean-Marc Nattier.

Empress Anna Ioannovna (reigned 1730–40) by Louis Caravaque

(Wikimedia Commons)

A miniature of Catherine II, painted on porcelain by Andrei Ivanovich Chernyl, a serf who worked at the Imperial Porcelain Factory.

Peter III, Catherine’s husband, while still only a Grand Duke, by Pietro Antonio Rotari.

A miniature of Grigory Orlov, Catherine the Great’s lover for eleven years, in masquerade costume, painted in enamels on copper by Andrei Ivanovich Chernyl in the late 1760s.

Paul I (reigned 1796–1801), the son of Catherine the Great, by Semeonovich Shukin

Paul’s wife, Maria Fedorovna, by Giovanni Battista Lampi

Alexander I (reigned 1801–25) by George Dawe

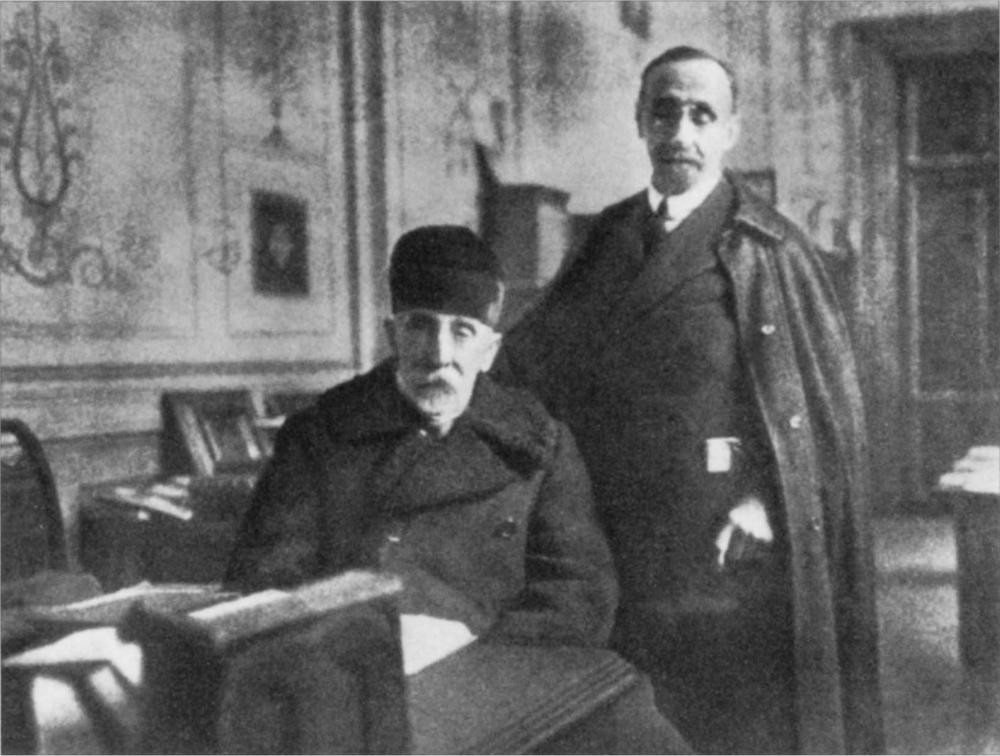

Sergei Nikolaevich Troinitsky, Director of the Hermitage from 1918 to 1927.

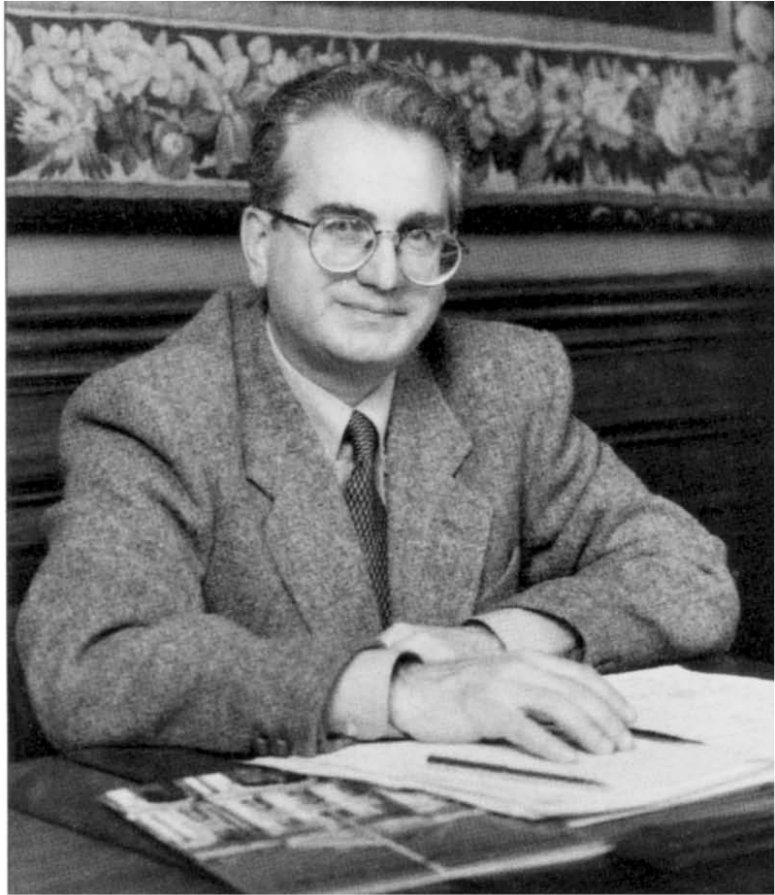

Alexandre Benois, artist, theatre designer, art historian and curator of paintings at the Hermitage from 1918 to 1926.

Josef Orbeli, Director of the Hermitage from 1934 to 1951.

Leonid Tarassuk, the curator of arms and armour who was sacked by the Hermitage in 1972 when he applied for a visa to leave Russia for Israel.

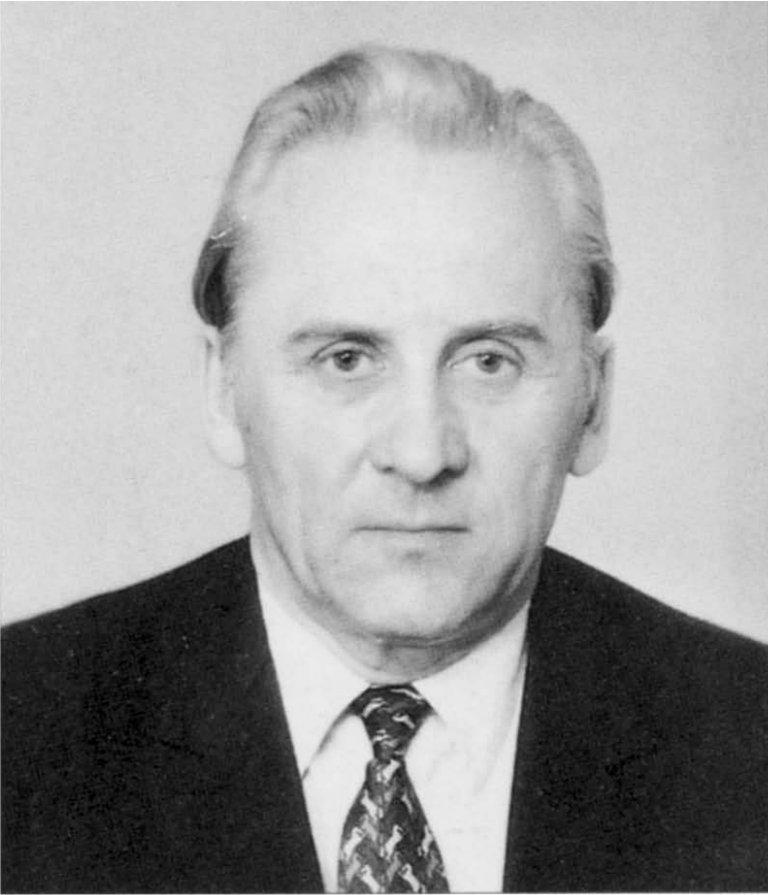

Boris Borisovich Piotrovsky, Director of the Hermitage from 1964 to 1990.

Vladimir Levinson-Lessing, curator of paintings, author of a history of the Hermitage collection, and Deputy Director until shortly before his death in 1972.

Mikhail Borisovich Piotrovsky, appointed Director in 1992.

Vitaly Alexandrovich Suslov, Deputy Director of the museum from 1967 to 1990, Director from 1990 to 1992.

Tolstoy’s departure left Eduard Lenz, the deputy director, in the hot seat when, to the horror of all concerned, the Futurist art historian and critic Nikolay Punin was appointed Commissar of the Hermitage on 1 August 1918; the Futurists were on record as favouring the destruction of all ‘old’ art. It was a bad month for Lenz. On 2 August the Collegium on Museum Affairs called for a radical reform of the Hermitage and on 15 August the museum received a telegram from Trotsky’s wife saying that she intended giving the Hermitage collections to the Moscow Museum of Fine Arts. Lunacharsky had appointed Nataliya Trotskaya head of the Museums Department in the Commissariat of Enlightenment’s Moscow office a few days before. Lenz endeavoured to orchestrate a mass resignation of keepers in protest at these moves but failed to carry his colleagues with him. On 23 August he resigned.

Troinitsky was now appointed acting director and, in order to satisfy the call for reform, it was decided to hold democratic elections for all curatorial posts. The electoral college was to comprise the existing keepers, as to one third of the vote, and delegates from St Petersburg’s main academic institutions for the remaining two thirds. On 11 November the twenty-eight delegates duly convened at the Hermitage and elected Troinitsky director. At the same time Alexandre Benois was elected keeper of the picture gallery and formally joined the Hermitage staff. Ernst Liphart, the former picture expert, considered himself too old for the job and his assistant James Schmidt had nominated Benois.

It was specified that the appointments were for one year only, after which there would be another round of elections. The electoral college was an essentially conservative body and the Hermitage became a haven for leading scholars who had lost their role in society as a result of the Revolution. Fedor Notgaft had been a rich private collector and now joined the staff as Benois’s principal assistant in the picture gallery. Alexey Ilyin, who had inherited his father’s cartographic business and was a keen collector of coins, now joined the numismatic department, later becoming its keeper and the deputy director of the museum. Mikhail Dobroklonsky, a young lawyer who had reached the rank of ‘privy councillor’ before the Revolution, was taken on in the prints department; he subsequently became the museum’s principal expert on Old Master drawings.

Orbeli himself was elected curator of art of the Muslim East in 1920, a post left vacant by the death of Yakov Smirnov. His principal mistress, Camilla Trever, was recruited in 1919. Also a trained archaeologist, she had been working as registrar of the Imperial Archaeological Commission and was out of a job when the Commission was gobbled up by the new Academy of the History of Material Culture.

The appointment of new staff begged the question of what the museum was going to do in the aftermath of Revolution. In August 1918 its future was threatened by the new ascendancy of the Futurists over arts policy, on one hand, and Mrs Trotsky’s efforts to keep the collections in Moscow, on the other. These issues loomed large for about a year.

The Futurists effectively cashed in on a vacuum. Lunacharsky was still being cold-shouldered by the vast majority of the cultured intelligentsia and he welcomed the Futurists’ desire to cooperate with the Bolsheviks, giving them charge of the Fine Art Section (IZO) of the Commissariat of Enlightenment. Punin later wrote: ‘There are few people who knew and felt the loneliness of the Bolsheviks in the first few months.’

The Futurists’ period of power was brief but wonderfully spectacular. Their poets and artists had already achieved a succès de scandale in 1913 by travelling round Russia on a ‘Futurist Train’ giving lectures and performances. They regarded themselves as ‘revolutionaries’ in the field of art; their credo embraced a passionate belief in technical progress and social change which they saw invigoratingly revealed by world war – the new, high technology of war, such as tanks and aeroplanes delighted them. In every field they tried to throw out old forms; poets rejected punctuation and grammar, painters embraced abstraction. Moreover, painting on canvas was old hat – they wanted it on the streets. On 1 May 1918 they literally ‘painted’ the city of St Petersburg to celebrate Labour Day. They decorated the most important buildings, bridges and embankments with red banners, multi-coloured proclamations, garlands of greenery and flags. Giant posters, painted in blazing colours, depicted noble soldiers and peasants.

Lunacharsky meditated: ‘It’s easy to celebrate when everything is going swimmingly and fortune pats us on the head. But the fact that we, hungry Petrograders, besieged with enemies within, bearing such a burden of unemployment and suffering on our shoulders, still are celebrating proudly and solemnly – this is our real achievement.’ The celebrations included a performance of Mozart’s Requiem in front of an audience of 7,000 at the Winter Palace, which Lunacharsky had recently renamed the ‘Palace of the Arts’. Aeroplanes circled overhead. There were fireworks and a parade of the city’s firemen wearing their brass helmets and carrying blazing torches.

In November, when the time came to celebrate the anniversary of the ‘October Revolution’, the artist Nathan Altman transformed Palace Square, decorating the central column with huge abstract sculptures and using 20,000 arshins (15,500 yards) of canvas to drape the Winter Palace and the other buildings with Cubist and Futurist designs. Meanwhile, inside the ‘Palace of Arts’ itself, Punin and the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky organised a conference for ‘the wide working masses’ on the theme ‘A sanctuary or a factory?’ Mayakovsky suggested that the Winter Palace should be turned into a macaroni factory. ‘We do not need a dead mausoleum of art where dead works are worshipped,’ he said, ‘but a living factory of the human spirit – in the streets, in the tramways, in the factories, workshops and workers’ homes.’ He proclaimed a similar message in a poem titled ‘Orders on the Army of Art’, which was published in the November 1918 issue of the semi-official newspaper, Art of the Commune, edited by Punin. No wonder the staid museum curators shook in their shoes. Lenin, however, had also seen a copy of this publication and urged Lunacharsky to tone things down. And by 1920 Lunacharsky himself had lost heart with the Futurists. They had proved ‘unacceptable to the masses’, he wrote, ‘although they showed much initiative during popular festivals, good humour and capacity for work of which the “old artists” would have been absolutely incapable.’

Punin’s impact on the Hermitage turned out to be minimal – he gave up the role of Commissar in 1919. His best remembered initiative is the First (and last) Free Exhibition in the Winter Palace, which opened on 13 April of that year. The idea was an exhibition without a jury or vetting committee – everyone was allowed to show what he or she liked. There were 2,000 works by 300 artists whom the catalogue listed in strict alphabetical order, making no distinction between them on grounds of fame. The nineteenth-century Wanderers were represented – there was even a work by Repin – alongside the Futurists and Cubists and the Hermitage Museum staff. Benois exhibited, as did two artists he had recruited to work in the picture department, Georgy Vereisky and Stepan Yaremich. Vereisky is famous for his portrait drawings of leading artistic figures of the 1920s, while Yaremich’s lasting contribution to the Hermitage was a collection of Old Master drawings that he bought with an acutely discerning eye, mainly in Paris, before World War I. The artist who sent the most pictures to the Free Exhibition, however, was Chagall with a total of twenty-four. He was also caught up in the Revolution, becoming Communist Commissar of art in the city of Vitebsk.

The Hermitage staff also managed to mount a major exhibition in their galleries before the collections returned. Its centrepiece was a group of pictures from the collection of Grand Duke Constantine whose family had lived in the Marble Palace up until the Revolution. At first uneasy about the ethics of working with confiscated property – in early 1918 Yatmanov told them they could take what they liked from the Marble Palace but they refused – Benois and Troinitsky had bowed to the realities of the new situation when they were told that the building was being handed over to the military. From that point onwards, they seem to have taken the view that moving art works from nationalised collections to the Hermitage was a valid means of ensuring their safety.

The exhibition, which opened on 22 April, six days after the Free Exhibition in the Winter Palace, contained pictures from various sources besides the Marble Palace: from Tsarskoe Selo, the country palaces of Gatchina and Peterhof, and from collections that Tolstoy had stored in the Hermitage for safekeeping. There were also some works of art recently purchased from collectors who were emigrating. Lunacharsky had managed to secure purchasing funds for the museum to use for this purpose – prices, of course, were rock bottom. The exhibition could be said to mark the beginning of the immensely complex transfer of private art collections to the Hermitage, and through the Hermitage to other museums and for sale abroad.

The Free Exhibition was only one of the many uses to which the state rooms of the Winter Palace were put during its period as Lunacharsky’s ‘Palace of Art’. Films were shown regularly in the Nicholas Hall and concerts were held in the Armorial Hall, which had seating for 1,200 but could, at a pinch, accommodate 2,000. There were also lectures – the lecture on colour photography was so popular that it had to be repeated two weeks running. Yury Annenkov mounted a Futurist production of Leo Tolstoy’s play, The First Distiller, in the Armorial Hall. ‘The scenery was made up of multicoloured crisscrossing ropes,’ he later remembered, ‘slightly camouflaged trapezes, various swaying platforms suspended in space and other circus equipment, against a background of abstract blobs of colour, primarily in a fiery spectrum. The devils flew and tumbled in the air. The ropes, trapezes, and platforms were in constant movement. The action developed simultaneously on the stage and in the audience.’

In November 1918 the Palace was used as a dormitory for several thousand participants who came to St Petersburg for the Congress of Rural Poverty. It was discovered after the peasant delegates left that they had filled both the Palace bathtubs and many rare Sèvres, Meissen and Oriental vases with excrement. Maxim Gorky, despite his commitment to the Revolution, was among those shocked by this insult to the cultural heritage. ‘This was not done out of need,’ he wrote. ‘The lavatories in the palace were fine and the plumbing worked. No, this hooliganism was an expression of the desire to break, destroy, mock and spoil beauty.’

In October 1919, as the Civil War raged within a few miles of the city, Yatmanov, the museums commissar, revealed to Troinitsky his plans for a Museum of the Revolution in the Winter Palace. This proved a more enduring obstacle to the Hermitage’s takeover – it did not move out until after World War II when changes in ideology and the execution of many former leaders had rendered its original displays unacceptable. Its first rooms were opened in 1920 on a very simple basis; the old apartments of Nicholas I, Alexander II and Nicholas II were opened, with their original furnishings, as an illustration of the regime the Revolution had overthrown. Later, there were rooms devoted to the Decembrists, to the revolutionary movements between 1840 and 1880, to the Shlisselburg prison, to Tsarist ‘justice’ and exile, to secret printing presses in Russia, and other vivid manifestations of the revolutionary process.

With so much activity in the old Winter Palace, the Hermitage staff was pressed throughout 1918 to reopen the museum. Lenz categorically refused, saying that the collections were in Moscow, but when Troinitsky took over he agreed to open the antiquities galleries, whose marble sculptures had been too heavy to move. The keeper of Classical art, Oskar Waldhauer, was anyway keen to have them open to show his students. Troinitsky’s cooperative attitude was rewarded in September 1918 with an undertaking that the museum could take over the Small Hermitage, the riverside galleries of the Old Hermitage, known since the pictures moved out in 1852 as ‘the Seventh Spare Part’, and the Apollo Hall, which connected the Small Hermitage with the Winter Palace. Lunacharsky also backed Troinitsky in the battle with Mrs Trotsky, ruling that the Hermitage collections should return to St Petersburg rather than stay in Moscow. Troinitsky’s first victories soon proved pyrrhic, however – the First Free Exhibition was allowed to spill over into the Small Hermitage while the return of the collections from Moscow was again challenged in December 1918.

This time the keepers read in the newspaper that the Council of People’s Commissars (Sovnarkom), Lenin’s inner cabinet, had decided to open the crates of treasures from the Hermitage and other St Petersburg museums and put them on exhibition in Moscow. They rushed round to Gorky’s flat on 5 December and with his help put together a telegram that was despatched to Lenin, with a copy to Lunacharsky, now also based in Moscow: ‘Extremely concerned at the danger threatening the treasures of the Hermitage, Russian Museum and Academy of Arts in the Kremlin Palace,’ it read, ‘as a result of the exhibition idea which will mean the unpacking of the boxes without the observation of proper guarantees of safety. The council of the Hermitage has gathered in the home of Maxim Gorky and unanimously sends a plea that you prevent the organisation of the exhibition and do everything you can to achieve the return of the collections to Petrograd which is the sole means of saving the treasures.’ It was signed by eleven senior keepers and Gorky himself.

The telegram did the trick, but moving the collection proved impossible owing to lack of transport or food for transport staff and in May 1919 Mrs Trotsky was at it again. This time the Hermitage Council discovered that she was planning to open a Museum of Western Art in Moscow based on the Hermitage collection. Troinitsky wrote a letter to the Moscow Collegium of Museum Affairs on 27 May conceding that some of the Hermitage collection might be shared with other museums but arguing that the whole of the collection must first be returned to St Petersburg and ‘only after this can it be decided which parts of the collection are unsuitable to the Hermitage and can be transferred to other museums on the basis of an overall plan of museum construction’.

Troinitsky was summoned to Moscow to discuss the matter in person but was wily enough to know that his own class origins would tell against him. He asked Stepan Yaremich, the artist son of a peasant, and Vselovod Voinov, from the Engravings Department, who had been a lowly clerk before the Revolution, to go in his place – but the train was so full that only Voinov managed to climb aboard. He arrived in Moscow to find that a three-stage process had been determined on: first the controlled opening of the crates, second a Moscow exhibition and third a division of the spoils between Moscow and St Petersburg. He was shown the potential exhibition rooms and complained bitterly – the skylights were broken in the Museum of Fine Arts and rain could get in and damage the pictures. In any case, he said, the pictures could not be hung on its marble walls. Eventually Moscow seems to have realised that the exhibition could not be mounted without the collaboration of the Hermitage staff – which was not going to be forthcoming – and again the threat was lifted.

However, the Civil War was raging and there was no way the collection could be safely moved. So in September 1919 James Schmidt was sent down to Moscow to check the condition of the pictures. It was on this occasion that Schmidt visited the Shchukin and Morozov collections and had the brainwave of asking for a share of them to compensate for any Old Masters that Moscow might demand from the Hermitage. He managed to get the official backing of Lunacharsky and five years later, in 1924, a swap was duly negotiated. On paper, of course, Moscow got a much better deal than St Petersburg but the principle of sharing the two great modern art collections was established which led, after the second division of the pictures in 1948, to the Hermitage gaining a superlative collection of turn of the century art.

The re-evacuation of the Hermitage collection finally took place in November 1920; it began on 17 November, the day the Civil War officially ended. Yatmanov had secured a special train with a battalion of guards – it was assumed that the train would have to stop from time to time to gather fuel, so the art works would have to be guarded from theft. Young keepers were sent down from St Petersburg to organise the packing, including Orbeli, but in a last-ditch stand Mrs Trotsky refused to supply lorries to move the crates from the Kremlin to the station. These had to be sent down from St Petersburg as well. They were filled by day but only driven to the station in the middle of the night, accompanied by an armed guard, to avoid robbery. The first cases arrived home on 19 November and a banquet was held in the Malachite Room to celebrate.

The Rembrandt room was opened on 27 November, the other Netherlandish paintings on 12 December and the Italian paintings on 19 December. On 26 December the pipes burst. Through the desperate fuel shortages of the previous two years, the palace had been unheated. In winter the temperature in the museum had been between minus two and minus eight degrees centigrade – the keepers had worn fur coats and gloves to work. But in preparation for the receipt of the paintings they had been allowed a special fuel supply so that the temperature of the galleries would not damage the art. The old pipes were not up to this unexpected warmth. The water which drenched the paintings in the Italian room turned the varnish on the pictures milky but this proved easy to put right.

The Hermitage scholars were also busily involved with setting the newly nationalised palaces in order. Tsarskoe Selo, Gatchina, and Peterhof were the first to be opened to the public as artistic displays – the rarest, museum-quality works of art were subsequently transferred to the Hermitage. Pavlovsk was still lived in by the family of Grand Duke Constantine at the time of the Revolution and was only nationalised in 1918, at the same time as the great palaces of the old aristocracy. The palaces of the Stroganov, Yusupov, Shuvalov, Bobrinsky and Sheremetev families, all with composite collections formed by several generations of art lovers, were converted into mini-museums. The Hermitage keepers were called on to arrange the collections for display but this was easily squared with their consciences since the works of art remained in situ and, should the political climate have changed and the former owners returned, they would have found their possessions intact. The keepers were also asked to sort the art collections found in private apartments abandoned after their owners’ precipitate flight. A huge volume of material was brought to the Hermitage for storage and was inventoried there.

The Stroganov Palace was scheduled as a ‘branch’ of the Hermitage and Camilla Trever, the newly recruited archaeologist, was sent down the road to run it. In 1923 the Stieglitz Museum was also rescheduled as a ‘branch’ of the Hermitage – there was no place for rich private foundations in the new order – as was the Stables Museum which contained carriages used by the imperial family from the eighteenth century onwards. Between 1925 and 1930 the palace ‘museums’ were successively closed down and the collections passed to the administration of the so-called Museums Fund – as the Collegium on Museum Affairs had been renamed in 1921. The Hermitage and the Russian Museum were allowed to pick what they wanted and the rest went to the Museum Fund storage – they had two large storage depots, one of which was actually in the Hermitage.

The dismemberment of private collections was gradually followed by a parallel dismemberment of museum collections – the many specialist museums established with such idealistic intentions in the nineteenth century. The Stieglitz was closed and most of the contents transferred to the Hermitage between 1923 and 1942. The same happened to the museums attached to the Academy of Arts and the Academy of Science, the Society for the Encouragement of the Arts, and the Archaeological Society. The collection successfully repatriated from the Russian Archaeological Institute in Constantinople – no mean feat at the time – was also dispersed. Between the mid-1920s and the mid-1930s almost all smaller institutions were closed down and their collections absorbed by the Hermitage, the Russian Museum and the Museums Fund – some items went first to the Museums Fund and were only passed to the Hermitage at a later date.

The maintenance and security of a multitude of small museums posed impossible administrative problems. Professor Mikhail Dobroklonsky, who was in charge of the museum in the former Bobrinsky Palace before joining the Drawings Department of the Hermitage, used to tell his students horror stories about the uncontrolled thefts. On one occasion, when he was doing his rounds to check the collection, he actually found a thief hiding in a chimney.

The concentration of collections was also politically in tune with the times. Stalin was busy with his brutal collectivisation of agriculture, whose advantage lay in replacing a multiplicity of small farms by large units responsive to directives from the centre. Clearly, the government’s cultural policy could be more easily imposed on a few large museums than on quantities of quirky, individualistic institutions. And Stalin was looking everywhere for potential sources of foreign currency in order to pay for the industrial equipment that was vital to his ‘five year plans’ and the rapid industrialisation of the country. Works of art from the Museum Fund stores, and from the museums themselves, were sold on a massive scale between 1928 and 1932. The sales stopped when the Depression had effectively closed down the Western art market and there was no more demand for Russian treasures.

While the Hermitage gained a few church treasures and a large volume of art from private collections as a result of the Revolution there was a terrible outflow. The most damaging losses were the Old Master paintings ceded to Moscow, which have turned the Pushkin Museum into a great picture gallery. The negotiations, as we have seen, began in 1918 and were not concluded until 1924. Between 1922 and 1924 Alexandre Benois and his colleagues in the Picture Department fought a rearguard action to avoid handing over major paintings. They managed to keep hold of the dazzling core of the collection but a total of seventy-eight paintings from the pre-Revolution Hermitage galleries were despatched to Moscow. Paintings from the old private collections of St Petersburg were also divided between the Hermitage and the Pushkin – notably the Yusupov collection. The Pushkin ended up with some 400 St Petersburg paintings. The Hermitage managed to argue that such generosity should be reciprocated and got around one hundred of the Shchukin and Morozov paintings from Moscow, including works by Sisley, Monet, Cézanne, Van Gogh and Gauguin.

Once Moscow’s claims were satisfied, it became the turn of Poland. Under the terms of the Russo-Polish peace treaty of 18 March 1921, a miscellany of Polish works of art which had been acquired by the Hermitage over the centuries were ceded to Warsaw. These included Bellotto’s famous series of Views of Warsaw, with whose help the old city centre was reconstructed after World War II, a Rembrandt Portrait of Martin Soolmans, Salomon van Ruysdael’s Whitening Sheets Near Haarlem, and the coronation sword of the Polish kings which had disappeared from the Wawel Palace in Cracow in 1795 and entered the Hermitage along with the Basilewski collection. The Poles also claimed Fragonard’s The Kiss, which the Hermitage had acquired in the eighteenth century with the collection of Catherine the Great’s lover, Stanisław Poniatowski. However, the Hermitage managed to retain it by offering the Poles Watteau’s Polish Woman in its place.

Next, the various republics making up the Soviet Union wanted to develop their own museums and expected the Hermitage to supply them with exhibits. ‘Beginning in 1932,’ according to Mikhail Piotrovsky, the museum’s present director, ‘hundreds of paintings and objects of the decorative arts were transferred to picture galleries all over Russia, Ukraine, Belorussia, the Caucasus and other parts of the Union’. A particularly large volume of material was handed over to the Ukraine. Listed in the Acts of Transfer were ‘tens of thousands of items – archaeological finds, gold and silver, paintings, Zaporozhian banners, documents, objects associated with the Ukraine and objects not associated with the Ukraine’. Most of them, Piotrovsky notes, were looted or destroyed during World War II.

The sufferings of the keepers were not confined to losing artworks which they would have liked to believe inalienable Hermitage property. Political repression and the politicisation of art history began to invade the museum in the second half of the 1920s. Benois presumably saw it coming. He had been allowed extraordinary freedom to visit his family in Paris. In 1924 he duly returned from a long trip abroad but in 1926 he took leave of absence and never came back; he gave the key of his St Petersburg apartment to the curator Stepan Yaremich who visited him in Paris that summer and some of the papers that Yaremich rescued are now in the Hermitage archive.

In May 1927 Troinitsky was relieved of his duties as director as a result of a long and bitter struggle with Orbeli who was building his Oriental Department with single-minded determination and complete lack of consideration for the rights of other curators – but who managed nevertheless to keep on good terms with the authorities in Moscow. Troinitsky was demoted to head of the Applied Arts Department and from 1931–5 worked for Antiquariat, the iniquitous sales organisation which stripped the Hermitage of so many of its treasures. He was subsequently arrested and sent into internal exile; the story of his tribulations will be told in a later chapter. Troinitsky was replaced as Director by Oskar Waldhauer, the museum’s specialist on Classical history. But Waldhauer was only classified as ‘acting director’ and was himself removed from power the following year, simultaneously resigning from the museum’s ruling Council.

This was at the time when Stalin had been consolidating his power. In the spring of 1928 he staged the first of his ‘show trials’, charging fifty-three engineers from the Shakhty mining district in south Russia with economic sabotage of Soviet enterprises at the behest of foreign intelligence agencies and White emigre former owners. Despite obvious signs that several defendants had been tortured to extract ‘confessions’, they were found guilty and five of them were shot. Thereafter purges spread into every branch of society and most especially affected St Petersburg intellectuals. One group would denounce another, only to find themselves denounced by a new wave of activists.

After Waldhauer’s resignation as ‘acting’ director in February 1928, five different directors were appointed in quick succession. None of them had anything to do with the museum – they were political activists and were presumably introduced in order to whip the old guard curators, with their dubious class origins, into shape. The speed at which they replaced each other reflects the ease with which party activists made and lost their reputations at this time. Some may have been repressed; the Hermitage has little or no information on their subsequent histories. ‘The Marxist authorities did not last longer than six months,’ Tatiana Tchernavin tells us in her memoirs. ‘They were replaced by others of the same stamp; the learned experts who happened to come into conflict with them were dismissed from their posts or found themselves in prison.’

In the official history of the museum, the former director Boris Piotrovsky sets out some indications of where these men came from. German Lazaris, who was in charge from February to December 1928, was a non-party man from Moscow with no previous experience of museums, he says; he could have been one of the undercover police agents who were assigned specially sensitive tasks at this period, but not necessarily under their own names. He was replaced by Pavel Klark, who lasted exactly a year. Klark had exemplary qualifications as a revolutionary, having been sentenced to death by the imperial regime in 1906. The sentence was subsequently commuted to fifteen years’ hard labour and Klark succeeded in running away to live in Japan and Australia before returning to Russia in 1917. In his memoirs, Piotrovsky unbuttons a little and adds that Klark was ‘very ill, very short and unhealthily fat’.

Klark was ostensibly appointed with the job of injecting Communist ideology into the Hermitage display but he displeased somebody and was replaced by another outsider, Vladimir Zabrezhnev, who lasted just under two months. He in turn handed over in February 1930 to Leonid Obolensky, a literary publisher and party activist; the Hermitage archives contain a quantity of texts written to prove he had no connection whatever with the princely family of the same name. Obolensky had previously worked for the Ministry of Finance and is said to have been opposed to the sale of museum treasures which was going on at the time. He is the only one of the five short-lived directors whose subsequent fate is known. A sick man when he was appointed, he died in October 1930 and was replaced by his deputy, Boris Legran.

Legran was a military and political man who had played an important role in the Civil War. A member of the Collegium of the People’s Commissariat for the Navy and of the Revolutionary Military Council on the Southern Front, he worked with the 10th Army on the defence of Tsaritsyn (now Volgograd) during 1918–19. In 1926 he was appointed ambassador to Armenia and took an active part in the Sovietisation of the republic. Piotrovsky clearly liked him. He describes Legran in his memoirs as highly educated, a wonderful organiser and very well dressed. Not so, according to Tatiana Tchernavin: ‘A former Soviet diplomatist, who disgraced himself in the Far East by drunkenness and scandalous love affairs, he was made as a punishment, director of the Hermitage,’ she writes. ‘It certainly was a punishment for all the museum workers; he was very rude, and was hand in glove with the OGPU [the secret police].’ Tchernavin’s venom may reflect the fact that Legran refused to take her back on the Hermitage staff when she came out of prison.

When Legran was appointed deputy to Obolensky, it must have been on the understanding that he would subsequently take over from the sick director. And he proved to have exceptional staying power by the standards of the time – he remained director of the Hermitage for three years and ten months. It was during his term of office, in 1931, that the Workers’ and Peasants’ Commission of the Russian Federation arrived to check out the backgrounds of the Hermitage staff. Mass sackings were called for on the grounds of the curators’ unacceptable class origins and contacts with foreigners. However, for some reason the authorities decided to be merciful and a good number were re-engaged.

The Hermitage still has a document listing the ‘filth’ of the museum: there were no White Army officers or imperial policemen, but there were seven officers of the old army, one factory owner (Alexei Ilyin, head of the Numismatic Department, whose family mapmaking firm was nationalised and transformed into the official State cartographers), five children of ‘those who followed religious cults’ (i.e. priests), four traders and merchants and fifty-five nobles. Piotrovsky records that the Hermitage staff were particularly angry about the dismissal of Ilyin who was ‘old and very respected, partially paralysed, and stood holding up his head with his hand as he was attacked by young and energetic people’. He was eventually rehabilitated and returned to his post. All the accused were allowed to continue working in the museum until their appeals were heard

Tchernavin gives a vivid account of the Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspectorate’s ‘sifting’ of the political acceptability of the Hermitage staff:

Factory hands were put on committees to investigate the ‘trend’ of the work and the suitability of the staff. Good old workmen who had been minding machines for the last 20 years, and uppish young men of the new type – machinists, electricians, stokers – were brought into laboratories and studies filled with books. They were shy, astonished, interested, and utterly at a loss what to believe. It all seemed to them rather like black magic. It was hard to decide whether all these books and those elderly, spectacled scholars were doing good or harm to the proletarian state.

It looked as though the sifting might prove a failure, and ‘the class enemies’ would not be detected. Then members of the OGPU and the Communist party confined the inquiry to the social origin of the intellectuals, their liking for the old regime and so on. So-and-so had once held a post in such-and-such a ministry, so perhaps he was a friend of the Minister. That man’s wife was a countess or a princess by birth, or a general’s daughter, or something of the sort. This one, though he was not a gentleman by birth, like the others, continued to write in the old spelling; and that man there said ‘gentlemen’ instead of ‘citizens’ or ‘comrades’.

Such a method greatly simplified matters, and soon most of the experts and specialists received notices of dismissal ‘in the 1st category’ – ie, without the right to seek employment elsewhere…. The sifting lasted for a couple of months. When it was over, the authorities, after bidding amiable goodbye to the bamboozled workmen, began to understand that the work of the learned institutions could not be carried on. There was no one to replace the highly-qualified specialists who had been dismissed, and so most of them were ‘temporarily’ left at their posts. But time had been lost, work interrupted, peoples’ nerves wracked – all for the sake of a show of ‘proletarian watchfulness’.

The ‘sifting’ of curators was accompanied by an ideological reorganisation of the museum exhibition on which Legran published a booklet in Russian and French in 1934 titled The Marxist Reconstruction of the Hermitage. The reorganisation began in the autumn of 1930 and drove Tatiana Tchernavin and the more conservative curators to despair. ‘We were commanded in the shortest possible time to reorganise the whole of the Hermitage collection ‘on the principle of sociological formations,’ she writes.

No one knew what that meant; nevertheless, under the guidance of semi-illiterate half-baked ‘Marxists’, who could not tell faience from porcelain or Dutch masters from the French or Spanish, we had to set to work and pull to pieces a collection, which it had taken more than a hundred years to create…. OGPU reigned supreme everywhere, either openly or through party committees interfering with all one did and striving to fit everything into the narrow and often senseless framework of party instructions enforced by utterly ignorant people. Everything had to be arranged on ‘Marxist’ lines. The way it was done can be judged from the following conversation between the members of our staff at the Hermitage.

‘Do you know in what year feudalism came to an end?’

‘In what year? What are you talking about?’

‘We’ve just been to a committee meeting for furthering Marxism and have been informed that feudalism came to an end in 1495.’

‘What nonsense is this?’

‘Don’t you see, it was the year of the discovery of America!’

‘Is it supposed to have been the same in all countries, then?’ ‘The same everywhere. It was settled at the committee.’

‘That’s worth knowing!’

Another conversation, a month later.

‘Have you heard the latest?’

‘No, what?’

‘Feudalism came to an end in 1848.’

‘Another committee meeting?’

‘Yes, and it’s been settled for good. Keep it in mind.’

‘And what about the discovery of America?’

‘That’s been cancelled. It’s out of date, and to attach importance to it is “opportunism”.’

‘And how long will the decision of your committee be in force?’ ‘Till the next meeting, let us hope. Perhaps by then our Marxists will have read some other pamphlet.’ This was how young Communists implanted Marxism, while old and intelligent experts helplessly watched them do it. Everyone who protested was immediately declared to be a class enemy and a ‘wrecker’.

Tchernavin is, no doubt, unfair to those who were attempting to rewrite history at this time. What they were up to was in parallel to the more recent Western rewrites that have resulted from changed attitudes to the British empire or to race discrimination. However, Russia’s Marxist revision of history had special repercussions. James Schmidt, who had charge of the picture gallery, and Troinitsky, who was the head of applied arts, were both numbered among the ‘class enemies’. The two departments were combined into a new ‘Department of Western European Art’ and a former guide from the Museum of Revolution, Tatyana Lilovaya, was put in charge of it.

In order to conform with the new Marxist approach to art, the galleries were rehung and a new display combining pictures and applied arts was opened. This proved a convenient way of masking the disappearance of several of the museum’s best-loved masterpieces which had been sold abroad. Even Hermitage habitues had no way of telling whether the paintings had left the museum or just been tucked into store.

Legran adopted a lofty tone in his 1934 pamphlet to describe how the Hermitage was brought into line with political orthodoxy. He calls the reconstruction of the museum ‘an academic exercise based on dialectic materialism’, and goes on to explain that ‘the aim of the reconstruction of a Soviet museum is to present an exhibition whose themes are completely in tune with the ideology of the proletariat. Dialectical materialism, which uses Marx and Lenin’s scientific methods to explain natural phenomena, society and their laws of evolution, reflects the ideology of the proletariat and exclusively determines the direction of academic studies in a Soviet museum.’

Since the picture galleries were the most important part of the museum, they were attacked first. French eighteenth-century art and artefacts were available in such abundance that it proved possible to put on a show that included every aspect of ‘material culture’ along with the pictures themselves. It opened in 1932 and was arranged in two sections, ‘French art in the era of disintegration of feudal society and the bourgeois revolution’ and ‘French art in the era of industrial capitalism and imperialism’. Other new exhibitions included: ‘Italian art in the era of disintegration of feudalism, 14th–15th centuries’, ‘German art at the time of the peasant war, 15th–16th centuries’ and ‘German art in the era of industrial capitalism’.

One positive feature of the 1932 exhibition was the showing of newly arrived pictures from the Shchukin and Morozov collections. Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painting was not yet considered too degenerate to show to the general public – that was a post-war phenomenon. Monet and Manet were shown as examples of ‘art of the era of the highest development of pre-monopolist capitalism and the first attempt at a proletariat dictatorship’, Van Gogh and Gauguin as ‘art of the era of rotting capitalism’, and Matisse and Picasso as ‘art of the era of imperialism’.

Legran’s pamphlet explained that the old keepers knew their subjects very well but had no understanding of ‘history’. ‘Most of them have now adopted the new ideology and the methodology of Marx and Lenin in their academic work’, he wrote, but to achieve this it had been necessary to recruit new staff – Marxist historians, art historians and experts on literature – to work with the old guard and teach them new ways. The need for this was most ‘urgent’ in the department of Western European Art; ‘the gallery of paintings and the applied arts section were the weakest parts of the old Hermitage in terms of academic understanding’, says Legran.

In contrast, Legran describes the Oriental Department as the most advanced: ‘possibly the most remarkable department of the entire Hermitage’. He seems to have been overwhelmed by Orbeli’s brilliance and to have adopted him as his scholarly mentor. Orbeli became his deputy in 1933 and when Legran left the Hermitage in 1934 to become director of the Academy of Arts – a demotion which was reputedly followed by a police investigation which led either to a heart attack or suicide (accounts vary) – he saw to it that Orbeli succeeded him as director. In The Marxist Reconstruction of the Hermitage, Legran describes Orbeli’s empire building with vivid enthusiasm.

In 1921, when Orbeli was a one-man department of Muslim art, there had been 7,000 Oriental items spread around various departments of the Hermitage. By 1934 there were 84,000 pieces; the new department had sought out Oriental treasures from the museum stores of St Petersburg and elsewhere in Russia. Legran lists the Institute of Archaeology, the Stroganov collection, the Bobrinsky collection, the Academy of Art, the Academy of Sciences, and the Russian Museum. The academic studies of the Oriental Department, he says, were in advance of any other section of the museum and he remarks in a footnote that responsibility for this lay with ‘I. Orbeli and the group of his students who were closest to him.’

Orbeli’s achievement was, indeed, remarkable. The department he created had, within a decade, gained a worldwide reputation for its scholarship, despite the limited contacts between Russia and the rest of the world, and it still has curators with international reputations. In 1935 Orbeli played host to the Third International Congress on Persian Art. The Hermitage devoted eighty-four rooms to a dazzling exhibition drawn from its greatly expanded collections, as well as loans from museums in the Soviet republics of the Caucasus and Central Asia, from Iran itself, from the Louvre and from America. Orbeli and his beautiful curator of Sassanian silver, Camilla Trever, played host and hostess to a gathering of over 300 scholars drawn from eighteen countries.

Legran explains Orbeli’s outstanding achievements on the grounds that the ideas of archaeologists are far in advance of those of art historians. ‘The history of art,’ he says, ‘is particularly backward among bourgeois academic disciplines.’ The reconstruction of the Hermitage thus came to put a special accent on archaeology. The Greek and Roman Department, where the presentation was previously almost exclusively ‘artistic’ was reorganised and, in 1931, a new department of ‘primitive society’ was established. ‘The exhibition of primitive culture, stretching from the very origins of human life, to the beginning of property ownership, class structures and the nation state, must be one of the most essential features of the general structure of the Hermitage,’ says Legran.

It is a curious fact of Soviet life that archaeology proved so much easier to analyse in terms of Marxist theory than art history. Nikolay Marr had shown the way in 1919 by persuading Lenin to back the establishment of an Academy of Material Culture to replace the imperial Archaeological Commission. ‘Material Culture’ is a perfect Marxist euphemism. In its name Orbeli was to launch the Hermitage’s direct involvement in archaeological excavations, thus adding a new and important dimension to Hermitage activities. He took over from Legran as director of the Hermitage in 1934 and was to hold on to the job for almost two decades, notably defending the museum through the agony of World War II.