During the post-war years Sergey Troinitsky’s role in Hermitage history was consistently underplayed. A pair of scissors was used to snip his image out of a group photograph of senior staff in the museum history by Sergey Varshavsky and Boris Rest published in 1978. Snipping people out of photographs was a standard Soviet technique for editing history. Troinitsky was the only director of the Hermitage to be arrested and prosecuted by the security police. He was found to be a ‘socially dangerous element’ and sent into internal exile in 1935.

He had been demoted from the directorship in 1927 following a ferocious battle with his successor Iosif Orbeli, who fought with most of the older staff of the museum on his way to the top. Troinitsky then spent four years in charge of the Applied Arts Department before being sacked by order of the Workers’ and Peasants’ Commission in 1931 and banned from holding any administrative post for the next three years. He was given a lowly job by Antiquariat, the government sales organisation that stripped the Hermitage of so much of its art in the 1920s and 1930s. Thereafter Orbeli blamed Troinitsky for the Hermitage sales – which, as we have seen, he actually fought relentlessly. Since many Hermitage staff owed their careers, or even their lives, to Orbeli, Troinitsky’s reputation suffered.

In contrast, Orbeli’s memory has been hallowed within the museum. He plays a heroic role in everything that has been written about its twentieth-century history, most especially on account of his defence of the Hermitage in the first terrible year of World War II when Leningrad was under siege. This is also somewhat misleading. Orbeli’s fiery temper did much damage despite his many positive achievements and the brilliance of his scholarship. He caused chaos within the museum when he was building up the new Oriental Department in the 1920s and, in consequence, it was a deeply unhappy institution that was handed over to the sequence of Soviet apparatchiks who were appointed to run it – and impose Marxist attitudes – between the departure of Troinitsky and Orbeli’s own appointment as director in 1934.

The battle between the two men helps to underline the confusion of right and wrong which is inevitable for those who try to live normal lives within a police state. In the extraordinary atmosphere of the late 1920s and 1930s in Russia, as Stalin launched his reign of terror even playing office politics was dangerous for all concerned. And Orbeli played office politics with a single-minded passion in order to get his own way that accepted no restraint. On occasion, he played in the same spirit in the national cultural arena and a number of those who got in his way ended up in prison or worse. When his protégés or friends were arrested, however, he did everything in his power to rescue them, repeatedly risking his own skin. Black and white, good and bad, are not applicable in these conditions. Troinitsky and Orbeli were both great men, great achievers on behalf of the museum which they both loved. Both were good scholars – but rivals.

Their fight was mostly to do with their contrasting characters rather than issues. In fact, there was only one issue – whether Orbeli’s Oriental Department deserved to expand at the expense of other sections of the museum. Luckily for Troinitsky, the battle took place in the mid- to late 1920s, before Stalin’s terror had really begun. Orbeli had nothing to do with Troinitsky’s arrest in 1935, which, according to the latter’s daughter, was merely on account of his noble birth. He was sentenced to three years internal exile in Ufa, an easy option. In the 1940s he lived in Moscow, where he had considerable difficulty finding work – his former qualifications did not count under Soviet rules – but eventually had a brief spell as chief curator of the Pushkin Museum where he built a new Applied Arts Department.

Troinitsky, born in 1882, was only five years older than Orbeli. He was thirty-five at the time of the Revolution while Orbeli was thirty. At that stage Troinitsky was the more obvious achiever. A man of means as well as noble birth, he had studied law and read lectures at Munich University while still in his twenties. In 1905 he founded the Sirius printing house, which was to publish the two most important art journals of the period, Apollon and Starye Gody. He was caught up with all the leading figures of the Russian Silver Age and the renaissance of interest in the visual arts which they cultivated. He began work at the Hermitage in 1908 in the Medieval and Renaissance Section, moving over to objets de vertu in 1911. He ended up with an encyclopaedic knowledge of porcelain, silver and the other applied arts, as well as being an expert on heraldry. Charming and popular, his election as director of the Hermitage in 1918 seems to have been a foregone conclusion.

All accounts are agreed that Troinitsky’s perfectly tailored elegance was an important part of his image, along with the red hair and beard and the pipe which he smoked continuously – although he switched to chain-smoking cigarettes after he lost a lung to tuberculosis during his exile. His daughter Elena remembers how his elegant figure in a well-made grey suit fitted harmoniously into the rich, old-fashioned decoration of the Antiquariat building in 1934. Troinitsky himself enjoyed this fitness, she says, taking an aesthetic pleasure in it.

Like Orbeli, Troinitsky seems to have been dangerously attractive to women. Elena, born in 1913, and her elder sister Nataliya were his only official children. He left their mother, Varvara Timrot, directly after Elena’s birth and she did not meet her father until 1934. His second wife Marfa was previously married to Stepan Yaremich, the artist and collector who became a keeper of drawings at the Hermitage after the Revolution. The two men were old friends – Yaremich had worked with Starye Gody – and his demotion to the Restoration Department in 1927 may have been a result of Troinitsky’s disgrace. Even in the postwar years, colleagues remembered with affectionate amazement how Yaremich had loved his ex-wife so much that he would gather wood and carry it round to Troinitsky’s apartment to make sure she kept warm.

By 1934 Troinitsky was married to his third wife Marianna, the daughter of the famous artist Viktor Borisov-Musatov. According to Elena, Borisov-Musatov was ‘an outrageous hunchback and his daughter was an ugly person too. She had no children and a terrible character…. She was significantly younger than Troinitsky.’ Nevertheless, she followed him faithfully to Ufa and back to Moscow where they were not allowed official residence and slept on various floors – for a time they were allowed to camp in some outhouses of the Kuskovo Ceramic Museum. Mrs Troinitsky got a job stencilling script on shop windows while her husband taught at the Moscow Arts Theatre School where he had an affair and a child with the head of the Art Department, Alexandra Hohlova. He died in Moscow in 1948 and is buried in the corner of a cemetery reserved for the use of Hohlova’s family – even finding burial space was difficult for him.

Orbeli’s noble blood was even more ancient than Troinitsky’s. The Orbeliani had been one of the pre-eminent families of Armenia since the twelfth century. However, his style was more suited to a revolutionary age. He had a shock of untidy dark hair, a flowing beard and was habitually shabbily dressed. According to the memoirs of the weapons curator Mikhail Kosynsky, he used to make malicious jokes about anyone with pretensions to elegance. Friends remember the holes in his shoes during the war and the unconcerned way he marched around the Hermitage with wood shavings in his beard while its treasures were packed for evacuation in 1941. He is universally credited with a brilliant ‘eye’ for artistic quality but his scholarly interest lay in cultural history rather than aesthetics. Epigraphy was one of his central interests and he was even criticised by his admirer, Boris Legran, director of the Hermitage from 1930 to 1934, for laying too much stress on the history of language in the displays he created.

Orbeli, like Troinitsky, was a liberal who sympathised with the Revolution and wanted to play a role in shaping the cultural policies of the new regime. In 1919 he became the academic secretary of the Museums Department of the Commissariat of Enlightenment – the Bolshevik equivalent of the Ministry of Culture – but like Troinitsky, he never joined the Communist Party.

When Orbeli came to the Hermitage in 1920 to run a new department of the ‘Muslim East’, he had the personal backing of the two most important scholars in the new Soviet hierarchy, Nikolay Marr, director of the Academy of the History of Material Culture, and Sergey Oldenburg, secretary of the Soviet Academy of Sciences. Both were members of the Hermitage Council and the new department was their idea – as was the choice of its first director. Oldenburg himself was an Orientalist of exceptional distinction and was anxious to see the cultures of the East properly represented in the museum. In imperial times there had only been a section of the ‘Classical East’ in the Antiquities Department and Iosif Orbeli, then an ambitious young man, was given the task of building something bigger and better.

Orbeli’s ambition took the form of an assumption that what he was interested in was more important than anything else in the world. With his fiery temper, he blasted those who stood in his way and ignored accepted norms of polite behaviour; there was soon pandemonium in the Hermitage. He sought out Oriental artefacts in every section of the museum and demanded, with threats if necessary, that they be handed over to him. With Oldenburg’s loyal backing his fiefdom was extended in 1921 to the Caucasus, Iran and Central Asia and in 1926 was renamed the ‘Oriental Department’, thus taking in China, Japan and the great civilisations of the Far East. His patrons also got him appointed deputy director of the museum in 1924, from which position he could coerce reluctant curators to hand over their collections more effectively. It must be said, of course, that once the Oriental Department was established, it was only proper for Orbeli to take over responsibility for the Oriental possessions of the Hermitage – it was, rather, his manner of doing it that was at fault.

Orbeli’s papers, now in the Academy of Sciences archives, paint a vivid picture of the chaos he caused while building the department. There is a letter of complaint from other members of the staff dated 28 April 1925:

In recent times, the Director’s Assistant I. A. Orbeli has increasingly frequently used a manner of address towards employees of the State Hermitage which is impermissible in a State Scholarly Institution. Such a form of address is not only insulting to the staff, but also extremely harmful to work, creating a nervous atmosphere which totally precludes the ability to work calmly. In view of this we most strongly request that you protect the staff of the Hermitage from such a manner of address and thus create the conditions necessary for normal productive work.

The twelve signatories included the Egyptologists Nataliya Flittner, Boris Piotrovsky’s friend and mentor, and Militsa Matthieu, a committed Communist who was to become deputy director of the museum under Orbeli in 1941.

Grigory Borovka, the keeper of Helleno-Scythian antiquities, also signed the letter. He was to fight long and hard with Orbeli, who wanted Borovka’s collection for the Oriental Department. In 1927 Borovka resigned from the staff claiming that Orbeli had manufactured complaints against him in order to remove ‘a certain object’ from his care to the Oriental Department. He was criticised for launching an ‘unfair’ attack on Orbeli and persuaded to withdraw his resignation. He continued to have charge of the museum’s incomparable collection of Scythian gold until his arrest in 1930 – of which more later.

There were more complaints in 1926 that Orbeli was not scholarly and that he was always interfering in other people’s work. So clamorous were they, that he resigned from the administration in protest – or maybe in order to position himself better for attack. Resignation was one of his favourite levers for getting his own way throughout his career. He also liked a show of heavy formality, pressing his interest at meetings of the Hermitage Council in measured periods: ‘I addressed the Council’s attention at a sitting on 21 January of this year [1927] to the fact that I did not want to deviate from the narrow framework I had set over the issue of the essential requirements of the Oriental Department, which I was raising not for the first time, and pointing out the department’s difficult situation while it remains cut off from the very valuable and wide collections which should be under its control.’

He was asked to put his complaints in writing and penned a lengthy paper on ‘The Unscholarly Structure of the Museum’. His argument was that the organisation of the museum should not be divided by countries or periods but by cultures. And, of course, everything relevant to Oriental cultures should be handed over to his department: the Medieval Department should hand over Mauritanian faience, the Armoury Oriental weapons, the Classical East scarabs and carved gems…. The latter point was treated at particular length since the keeper had lent Orbeli a group of gems in 1923 which Orbeli had refused to sign for, and had then published as part of the Oriental Department collection, refusing to hand them back.

So important was his paper considered that a commission was set up to reconsider the structure of the museum. Its members included, among others, Marr, Oldenburg, Troinitsky and Orbeli himself. Troinitsky was quickly established as the ‘enemy’ of progress. In early February Orbeli wrote a letter in which he accused Troinitsky of deliberately setting a meeting to discuss the matter on dates when people from the commission, including himself, could not be present as they were at a conference in Moscow.

Around April Orbeli seems to have moved in for the kill. He adopted the simple strategy of sending a letter of resignation to the head of Glavnauka, the museum and university section of the Ministry of Culture in Moscow, rather than to the Hermitage administration, thus drawing the higher authority into the fight. He explained his action by saying that when he previously resigned in January 1926, Troinitsky tore his letter to pieces and threw it on the floor in front of his eyes. Troinitsky went to Moscow to try and make his peace, in which he appeared to have been successful. There followed a stormy meeting of the Hermitage Council at which Troinitsky called for a vote of confidence. However, as Orbeli thundered in yet another letter of resignation, Troinitsky would not leave the room and insisted on chairing the confidence debate himself. ‘If S. N. Troinitski is not removed as director, and overall as head of the institution,’ Orbeli wrote, ‘I wholeheartedly request that you allow me not to be a witness of the disgraceful things taking place in the Hermitage, since as an employee I am in effect a participant in behaviour with which I am totally unable to come to terms.’

Troinitsky was duly demoted to director of the Applied Arts Department, and Oskar Waldhauer, the head of Antiquities, was made acting director of the museum. Orbeli’s actions, however, caused such a storm of resentment among the staff that the following year a special commission had to be set up ‘for Resolving the Conflict between the Scholarly Personnel of the Hermitage and I. A. Orbeli’. Letters poured in to the commissioners: ‘Orbeli is personally arbitrary, although he has the habit of covering his form of behaviour with the appearance of formal justification’, ‘Orbeli who usually claims for himself the merit of strict observation of museum discipline, in reality is demanding and strict only with regard to others, and is himself a disrupter of the main rules of museum work’, ‘the vast majority of employees seek to reduce to a minimum even the most necessary official contacts with I. A. Orbeli and there is no chance whatever of regarding him as a comrade,’ and so on. The members of the commission wisely decided that resolving the conflict was beyond them. Their findings conclude by expressing the conviction that ‘the heavy atmosphere of work and relations created within the Hermitage has already improved and, if mutually desired, will disappear altogether’.

The destructive power of Orbeli’s rage is interestingly analysed in a diary kept by Sergey Oldenburg’s wife. As the helpmate of Russia’s leading scholar, she was drawn into Orbeli’s highly successful battle to discredit the archaeologist Sergey Zhebelev in 1928; Zhebelev was professor of archaeology at Leningrad University, had been the first chairman of the Hermitage Council in 1918, and had recently been elected an Academician. ‘At the height of his unbridled anger,’ Mrs Oldenburg writes of Orbeli, ‘when he is mastered only by anger and hatred, his good sense is silent. Like the most primitive person, he can blindly and cruelly bring harm to other people. But when the storm has passed, his inherent sense of kindness takes control and his common sense speaks once more. But often his earlier outburst of anger and hatred has already spoiled things too much.’

This was the case in the Zhebelev affair which snowballed into a national scandal, with both the Moscow and Leningrad branches of the Academy of Science formally voting to rescind the title of Academician which they had granted Zhebelev the year before. And then the security police began to take an interest. ‘Because of him, they have arrested three other people, Sivers, Waldenburg and now Benistevich,’ Mrs Oldenburg laments. Alexander Sivers was a curator in the Numismatics Department of the Hermitage and recent signatory to a letter of complaint about Orbeli.

By 1928 Stalin’s reign of terror was beginning and academic squabbles were no longer a matter merely of scholarly reputation. Over the following ten years the Leningrad intelligentsia was decimated and repression took a remorseless toll of Hermitage staff. More than fifty curators were arrested and sentenced to internal exile, prison, labour camps or execution. A bewildering variety of trumped-up charges were used – twelve of the staff were executed as spies. There were Japanese spies in the Oriental Department, German spies in the Coins and Antiquities Departments – fields where German scholarship had played a dominant role since the nineteenth century – there were Armenian terrorists plotting to overthrow the constitution and Ukrainian nationalists with the same end in view. Those who published articles in foreign scholarly journals were, of course, foreign spies, while at home noble birth was enough to convert the most harmless scholar into a ‘socially dangerous element’.

None of this had anything to do with the museum per se. It was a reflection of the madness that held the whole nation in thrall and can only be understood in the context of national history. The machinery of terror used by the government against its citizenry, which was not dissimilar to that previously used by the tsarist police, grew out of institutions established during the Revolution and Civil War when there was logic to hounding class enemies. A secret police reporting directly to the cabinet (Sovnarkom), and with extraordinary powers to interrogate and punish, was established in December 1917. Initially known as the Cheka – the Extraordinary Commission for Struggle with Counterrevolution and Sabotage – its name was changed several times over the years: to OGPU in 1922, NKVD in 1934, NKGB in 1943, MGB in 1946, and finally KGB in 1953; its role, however, did not change.

Legislation to establish concentration camps was passed in April 1919 and official figures show that by 1922 there were 190 camps containing 85,000 prisoners. The scale on which the machinery of terror was used between 1920 and 1925 was relatively modest but it remained in place. Then, following Lenin’s death in January 1924, Stalin moved cautiously to usurp absolute power. He managed to rid himself of the Left Opposition – Trotsky, Zinoviev and Kamenev – in 1927, and the Right Opposition – Bukharin, Rykov and Tomsky – in 1929. He contented himself at this time with their expulsion from the leadership – their trials came later.

The reign of terror began in earnest in 1928 with the show trial of fifty-three engineers from the Shakhty mining district in Southern Russia who were charged with economic ‘wrecking’ of Soviet enterprises at the behest of foreign intelligence agencies and White émigré former owners. As was to become the general rule, the case rested on confessions obtained through physical and psychological torture. Most were found guilty and five were shot. The horrifying process had begun of denunciation, arrest, torture, further denunciations and further arrests, which was to sweep a large proportion of the population into custody over the next decade. Honest men denounced their colleagues to save their own wives and children, signing crazy confessions which could lead to their own deaths.

The murder of Sergey Kirov, first secretary of the Leningrad Communist Party, on 1 December 1934, was a turning point. He was shot in the Party headquarters in the Smolny by Leonid Nikolaev, an embittered and deranged Young Communist. It is now believed that the murder was arranged by Stalin and the NKVD but, at the time, it was presented as part of a conspiracy that embraced half the population of Leningrad – including everyone Stalin wanted to get rid of. On the day of the murder Stalin issued a decree to speed up the investigation of ‘terrorist organisations or acts’; they were to take no longer than ten days and be presented to a military court which allowed no appeals and could order an immediate death sentence. This decree was to structure criminal justice for the next twenty years, until Stalin’s death in 1953.

There followed three show trials of party leaders. In August 1936 Grigory Zinoviev, Lev Kamenev and others confessed to having arranged Kirov’s murder and to being part of a ‘Trotskyist-Zinovievite Centre’ which had plotted the death of Stalin himself. In early 1937 a group including Karl Radek and Grigory Pyatakov confessed to spying, plotting assassinations and industrial ‘wrecking’. A similar string of offences were confessed by Nikolay Bukharin, Alexey Rykov, Nikolay Krestinsky and Genrikh Yagoda in March 1938. Most of the accused were executed. A crescendo of arrests among the population at large for related conspiracies followed in 1938–9. Finally Stalin realised that the scale of the operation was undermining the national economy – so much of the productive labour force was in custody – and brought the terror to a close in 1939. In the late 1940s, however, shortly before his death, he launched a new campaign against cosmopolitans and Jews.

It is against this background that the hounding of ‘enemies of the people’ on the Hermitage staff must be seen. They were particularly vulnerable since so many of them were of noble birth. Most of the St Petersburg intelligentsia had belonged to the nobility before the Revolution and it was natural that the scholar–curators at the Hermitage should have been drawn from this class. As every child of a hereditary noble automatically belonged to the nobility, the class was large and not especially elitist – more like the British ‘gentry’. There were also scholars who were made honorary nobles. Tatyana Tchernavin, for instance, was the daughter of a university professor who had had nobility conferred on him on receiving his degree although he was the son of a peasant. When she explained to her prison examiner that nobility conferred on individuals was not hereditary, she was accused of hiding her social origins and being a typical class enemy. As a result she was prosecuted for ‘furthering economic counter-revolution’.

‘There was no point in speaking about the accusation, which I simply did not understand,’ she wrote; ‘neither of the OGPU officers who examined me ever asked a single question relating to it…. I could not have explained what “economic counter-revolution” meant, to say nothing of my “furthering” it; history, literature and art were the subjects at which I had worked all my life. But charges against other prisoners were just as senseless, so that I was no exception.’

Arguments concerning ‘history, literature and art’ could, however, easily be twisted into political issues in such an environment. Tchernavin was arrested, more on account of her husband, a zoologist who was already in prison, than in her own right. Grigory Borovka, however, who was one of the first Hermitage staff to be repressed, was accused of being a German spy because of his involvement with plans for a joint Russo-German archaeological expedition to the Crimea. He was one of some one hundred scholars to be arrested in this connection in Leningrad and Moscow, the most prominent being Academician Sergey Platonov; the event has come to be known as ‘the Academicians’ affair’.

The affair had its origin in the collaboration between Russian archaeologists who had emigrated at the time of the Revolution and those who had stayed in Russia. The two groups had worked together before 1917 and continued to collaborate at long distance in the 1920s. This was particularly important to Borovka since Academician Mikhail Rostovtsev, who emigrated first to Oxford, then to Princeton, was the accepted world expert on the Scythians, his own area of study. Borovka worked with a group of other scholars, under Rostovtsev’s direction, to compile an anthology of studies of the archaeological monuments of Southern Russia. In this connection Rostovtsev’s book Sarmatia, Scythia and the Bosphorus was translated into German by the Hermitage curator Yevgeny Pridik; Borovka took Pridik’s manuscript to Berlin and was handed payment to take back to him in Leningrad. It is quite easy to see how this transaction came to be interpreted as espionage.

It was actually Orbeli who first interrupted the peaceful international collaboration of archaeologists with his campaign against Zhebelev. The scandal grew out of a volume of papers published in Prague in memory of the Hermitage scholar Yakov Smirnov, the great expert on Sassanian silver who had been Orbeli’s teacher. Zhebelev had contributed an obituary in which he wrote that ‘Yakov Ivanovich died on 10 October 1918, just when the terrible time of troubles was beginning.’ Smirnov had, in fact, died of hunger and Zhebelev’s words would have seemed fairly innocuous, had it not been for a paper by Rostovtsev published in the same volume that expanded and dramatised the issue. ‘It is painful to think,’ he wrote, ‘that if it had not been for the uprising, and everything connected with the uprising, hunger, despair, disillusion with both the present and future, Yakov Ivanovich would be with us still and we would be writing articles in his honour and not in his memory.’

Mrs Oldenburg’s diary explains what happened. Orbeli ‘was angry with Zhebelev for having referred several times in his article to unpublished material by Y. I. Smirnov which was in the possession of I. A. Orbeli. By these words, in Orbeli’s opinion, Zhebelev threw a shadow on his reputation (i.e. suggested plagiarism). Orbeli began to shout about the article everywhere, pointing out its non-Soviet tone, interpreting the unfortunate expressions and so on. By his shouts he attracted the attention of the Communists in the Hermitage to this article … and they were off’ As we have seen, the Zhebelev affair snowballed into a national scandal. The result was a ban on the publication of studies by Soviet scholars in émigré journals and a sharp cutback on their publication in any foreign periodicals.

The Zhebelev affair began in 1928 and rumbled into 1929 when it merged with the furore over Academician Platonov’s arrest for creating a counter-revolutionary monarchical organisation with links to the German spy system. Among those prosecuted as a result of the ‘Academicians’ affair’ were Alexander Miller, the professor of archaeology who taught two future directors of the Hermitage, Mikhail Artamonov and Boris Piotrovsky; Miller subsequently died in custody. And, of course, there was Grigory Borovka who was sentenced to ten years in the camps. He was let out in September 1940 but restricted to living in the Komi Autonomous Republic. At the outbreak of the war with Germany he was rearrested and shot.

Borovka’s story can be taken as an example of the human realities of repression. His family was of German origin – they had moved to Russia during the reign of Peter the Great’s daughter, the Empress Elizabeth. Thereafter they were mainly involved with theatre, music and art. His father was a professor of music at the Conservatoire and ran his own music school. Scared by the Revolution, the rest of the family moved back to Germany in 1918 where they no longer had any connections and lived in reduced circumstances. Grigory seems to have remained in St Petersburg for two reasons, the fascination of the work he was doing under Waldhauer at the Hermitage and the charm of his girlfriend, Katya Malkina, with whom he lived. She was also a curator in the Hermitage Antiquities Department but resigned in protest after Borovka’s arrest. A poet and a romantic, she later became a significant literary figure in her own right. She worked at the Pushkin House where, among other things, she compiled a bibliography of Nikolay Gumilev, the famous poet who was executed in 1921.

Borovka’s family still retain some moving memorials of his life, notably his letters to his mother and the postcards that Katya sent to keep the family informed about what was happening to Grigory after his arrest. In the 1920s he had taken advantage of every opportunity to visit his family in Berlin. In 1927 he was elected a corresponding member of the German Archaeological Institute and in 1928 he organised an exhibition in Berlin of artefacts from the Noin-Ula burial barrows. He also helped with the sale of Hermitage antiquities at the Lepke auction house, confiding in his family that he had miscatalogued the pieces in the hope they would not sell.

He was arrested on 21 September 1930, and remained in prison for over a year without trial while the OGPU gathered evidence on the ‘Academicians’ affair’; but they failed to turn it into the major conspiracy they had hoped for. Borovka was finally prosecuted as a German spy and sentenced on 7 October 1931, to ten years in the camps. He was sent to Ukhta, in the far north, where he studied palaeontology and set up a geological museum. Katya devotedly visited him in prison, sent him food packs and books and travelled to Ukhta on her summer vacations whenever she could manage.

On 30 September 1931 Katya writes to Borovka’s brother:

Gory sends you his greetings. He’s in good health – I’ve seen him three times. He’s now perfectly well nourished – much better than he would be if he was living with us; for the last two months I’ve been able to take him additional food (before that it was not allowed)…. He has the following request for you: if you have got the money from his book Scythian Art [published in London, 1928] stored up, could you buy two German books for him and send them to me – the third volume of Marx’s Kapital and the Dialektik der Natur by Friedrich Engels. If there is any money left over, could you send that too and I’ll buy him some food.

By 1934 Katya’s hopes were withering away. In April she wrote: ‘I don’t know whether it will be possible for me to visit Gory this summer. I am afraid that I won’t get enough holiday – it is such an endless journey. I can’t travel without getting news of Gory, but staying in touch by post is very difficult as letters take weeks on the way. Life in this world is often so terribly sad.’ In November: ‘Bad news from Gory; his health is not very good and he’s terribly depressed…. I help him as much as I can and send him parcels every month. His letters are rare and irregular.’ The postcards stopped in 1936 when Katya no longer had the opportunity to organise foreign correspondence. And the family knew nothing more of Grigory’s fate until 1994 when, at their request, the St Petersburg archaeologist Vadim Zuev found out what had happened to him.

Besides Borovka, two other Hermitage curators were arrested in 1930, Olga Fe, a noblewoman who worked in the Drawings Department, who was sentenced to three years in a concentration camp for spying – the sentence was later commuted to five years’ exile in Ufa – and the Orientalist Alexander Strelkov, who was arrested as an agitator and spent two years in prison before the case against him was dropped. Like, Borovka, Strelkov was later rearrested and shot as a German spy.

The next ‘plot’, which culled a swathe of Hermitage curators, was known as ‘the affair of the Russian National Party’ or the ‘Slavists’ Affair’ and erupted in 1933–4. The party was supposedly organised from abroad by the émigré fascist leader, Prince N. M. Trubetskoy, who argued the primacy of nations over class and publicly advocated an end to Communism and the establishment of a national government. The ‘plot’ was initially uncovered in the Ukraine but collaborators were subsequently found in Moscow and Leningrad. Two specialists from the Hermitage Armoury were among those caught up by it. The Kharkov Museum in the Ukraine had requested the loan of antique weapons for an exhibition and thirty-one pieces were duly despatched in June 1933 by the curators Alexander Avtomonov and Emile Lindroz. On 29 November and 1 December respectively, Avtomonov and Lindroz were arrested and accused of supplying arms to Ukrainian nationalists. Lindroz also had a private collection of antique weapons which was interpreted as ‘storing of weapons with the aim of using them in the organisation of an armed uprising’ – although he had written authorisation from the Hermitage for his collection.

Both of them were sentenced to ten years in the camps. In the case of Avtomonov, a second hearing took place in 1938, after which he was shot. Lindroz remained in the camps until 1945 and then became a watchman with the forestry commission in the Pestovo region, near Novgorod. He was still living there in 1956 when he was rehabilitated and the prosecution was expunged from his records as incorrect. There was a big campaign of rehabilitation of wrongly accused former prisoners three years after Stalin’s death.

An explosion of arrests at the Hermitage followed in the wake of Sergey Kirov’s murder. Vera Nikolaeva, an Egyptologist and art historian who worked in the ‘Classical East’ section of the Antiquities Department, was the first to go. She and her brother were arrested within days of the murder for the simple reason that they had the same surname as Kirov’s murderer, although there was no family connection. Accused of plotting to overthrow the constitution, her case was heard in June 1935 and she was sentenced to ten years in prison; the sentence was changed to execution on 4 November 1937, and she was shot on 17 November.

In February and March 1935 nearly all the former nobility who lived in Leningrad were arrested. There was a theory that Kirov’s murder was part of a counter-revolutionary plot in which many of them had collaborated. Alexey Bykov from the Coin Department, who had received his initial education at the college of the imperial Corps de Pages, was arrested as a former noble on 20 March and sentenced to five years’ exile in Samara. His exile was annulled in April 1936 and he returned to the Hermitage where he later became head of the Coin Department. Similarly Vera Gerts, a specialist on Poussin and French seventeenth-century painting, was arrested on 4 March and sentenced to five years’ ‘social defence’ in Astrakhan. She was freed on 25 April 1936, on reconsideration of her case. There were many others.

Troinitsky was one of those arrested on account of their noble birth. On 4 March a military court sentenced him to three years’ exile in Ufa and, according to the KGB records, he was not freed until 8 December 1938, rather more than three years later. According to his daughter Elena, however, a deputation of influential friends approached Stalin on Troinitsky’s behalf and obtained his early release. They included Alexey Shchusev, the architect who designed Lenin’s mausoleum, Vladimir Shchuko, one of the architects who designed the famous ‘Palace of Soviets’, and the mural painter Evgeny Lansere. ‘If he is not so dangerous he can return home,’ Stalin told them, according to Elena. ‘And Troinitsky was swiftly freed. But he did not return to Leningrad. It was too painful for him to do this. That is why he decided to live in Moscow.’

It was also at this time that Boris Piotrovsky, the future director of the museum, was arrested at a Shrove Tuesday pancake party thrown by a fellow archaeologist. His memoirs suggest that there were some real political activists at the party and that he and two other archaeologists, Andrey Kruglov and Georgy Podgaetsky, were arrested with them by mistake – they were accused of belonging to a terrorist organisation. Piotrovsky describes the room in the police station where he was taken which was divided from the corridor by a grille:

It was very, very full and people were sleeping on mattresses on the floor under the beds. When I went in many woke up and began asking with interest where I had come from and why I had been arrested. I couldn’t guess what I’d been arrested for. I had to occupy the last place which meant on the floor, under a bed, right up by the grille. As people were let out, the queue moved up and people occupied the places of those who’d left, so there was some hope that you would get a bed eventually. It was very uncomfortable. There were rats running up and down the corridor next to me and the guards threw their bunches of keys at them.

Kruglov and Podgaetsky were released on 10 April and Piotrovsky on 19 April, after forty days’ incarceration. The Hermitage took Piotrovsky straight back but he found that he and Podgaetsky had been sacked, in absentia, from the Institute of the History of Material Culture where both also worked. They took their hard luck story to the trade union, which decided, on 1 July, that the Commission of the Institute had been wrong and advised the two young archaeologists to take the Institute to court. They followed this advice and were duly vindicated and taken back, an extraordinarily ‘fair’ result by the standards of the time. It has been suggested that the successful court action protected Piotrovsky for many years to come; it would have been taken to mean that he had influence in high places and was therefore untouchable.

The story of the Japanese spies unearthed in the Hermitage in 1937 is almost unbelievable. Dmitry Zhukov, who had worked for the Russian government in Japan and joined the Hermitage Oriental Department in 1935, was arrested on 29 May 1937. Under torture he ‘confessed’ to having been lured into the service of the Japanese and having run a Trotskyite spy and terrorist group which included the poets Nikolay Oleinikov and Wolf Ehrlich, the writer V. Matveev and numerous Orientalists. Zhukov was shot on 24 November.

Among those he denounced under interrogation was Nikolay Nevsky, a Russian scholar who lived from 1915–29 in Japan where he is considered one of the founding fathers of ethnography. While in Japan he began to study the Tangut scripts that Kozlov had found at Khara-Khoto and was urged by Russian Orientalists to return to Leningrad and work on them there. He began to work at the Institute of Oriental Studies at the invitation of Sergey Oldenburg in 1930 and in 1934 joined the staff of the Hermitage. His Japanese wife and daughter joined him in Russia in 1933. After his arrest in 1937, Nevsky’s first priority was to defend them and it was for their sake that, after severe torture, he ‘confessed’ to working for the Japanese intelligence service and setting up a network of spies in Leningrad to gather information on military sites, aerodromes, factories, etc.

He did not know that his wife, who spoke no Russian, had been arrested four days after him and that his confession could not help her. Husband and wife were both executed on 24 November 1937, along with Zhukov. Nevsky was rehabilitated in 1957 and his Tangut studies, published in 1960, were hailed worldwide as one of the most important philological discoveries of the twentieth century. He was awarded a posthumous Lenin Prize in 1962.

In 1937–8 the conspiracies confessed to at Stalin’s show trials were found, with the help of torture, to involve an ever-widening circle of citizens across the whole Soviet Union. In the autumn of 1937 almost the entire leadership of Armenia’s Central Party Committee and Council of People’s Commissars was arrested. On the last day of the year eight of them were executed. The purge then spread to the Armenians living elsewhere. In February 1938 virtually every Armenian in Leningrad was arrested. The job was simplified for the NKVD by the fact that most Armenian surnames end in the letters ‘an’. On the night of 4–5 February – most arrests were made in the early hours of the morning – three Armenians from the Hermitage Oriental Department were arrested: Anton Adjan, Leon Gyuzalyan, and Gaik Gyulamiryan. Only Gyuzalyan survived; Adjan and Gyulamiryan were both shot the following October.

Orbeli was also Armenian by birth but he used the Georgian version of his surname, Orbeli, rather than the Armenian Orbelian and it is seriously suggested that this is one of the reasons he was not prosecuted. The three curators from the Oriental Department were all his ex-students and special protégés. Adjan, a specialist on Turkish art, had succeeded him as head of the Oriental Department when Orbeli became director of the museum in 1934. Orbeli leapt to Adjan’s defence. He took a train to Moscow the moment he heard of the arrest and sought out Anastas Mikoyan, the man to whom Stalin had given charge of the Armenian purge. He was not in his office and Orbeli announced that he would wait for his return. It was 2 a.m. when Mikoyan finally turned up and told Orbeli that he had come too late. Anton Adjan, he said, had already been executed. Curiously, the papers on Adjan’s arrest that have emerged from the KGB since perestroika show that he was, in fact, still alive at this point and was not executed for another nine months. Mikoyan had lied to get Orbeli out of his office.

It has also emerged that Orbeli himself was in grave danger at this time. Gyuzalyan, who returned to the Hermitage after the war, was pressured for many weeks by the NKVD to denounce Orbeli. The same happened to Alexander Strelkov, another employee of the Oriental Department – an expert on pre-Islamic Central Asia, Iran and India – who was arrested in February 1938 and executed the following September.

Gyuzalyan was eventually sentenced to five years’ corrective labour but was not, in fact, let out of the camps until after the war. He amazed his colleagues at the Hermitage by telling them that he had not known there was a war on. ‘There were some rumours about some trouble but we but didn’t know what,’ he told his close associate Adele Adamova – Gyuzalyan was an expert on Persian literature and Adamova on Persian painting. Like many other prisoners, he was banned from living in a large city after his release and only got back to Leningrad with Orbeli’s help. Though officially exiled ‘beyond the 100th kilometre’, Orbeli allowed him to work in the Hermitage from 1947 onwards. He was, no doubt, aware that he owed his own life to Gyuzalyan’s dogged refusal to sign a denunciation. In 1955, after Stalin’s death, Gyuzalyan was formally rehabilitated and officially re-recruited to the Hermitage staff.

Gyuzalyan and Adjan had been student friends and collaborators of Boris Piotrovsky. All three had worked on Urartu in the early 1930s though Adjan had then moved over to study Turkish art and Gyuzalyan Persian epigraphy. It was Piotrovsky who secured the posthumous rehabilitation of Adjan in 1956 and it was Piotrovsky whom Gyuzalyan first sought out in Leningrad after his release from the camps – still wearing the padded cotton jacket that was standard issue in the Gulag. The jacket ended up as a gift to the present director of the Hermitage, Mikhail Piotrovsky, for whom Gyuzalyan became a friendly, uncle figure. ‘He gave it to me when I went to do my agricultural labour as a first year university student, saying it would keep me warm.’

Gyuzalyan was loved and respected on his return to the Hermitage but the Gulag had robbed him of his best years and – cruelly – the NKVD had destroyed all his papers in 1938, including his laboriously compiled card file. He never had the heart to reconstruct it. ‘He would have been a very good scholar if he hadn’t lost all those years,’ comments his fellow Orientalist, Igor Diakonoff. ‘When he came back, he was already old and weak. It was a wonder that he survived.’ In fact, he was in his nineties when he died in 1994.

Orbeli’s courage and determination in defending his curators was also demonstrated in the case of Pavel Derviz, a silver specialist and former baron, who took over the objets de vertu department from Troinitsky. Arrested, like other nobles after Kirov’s murder in 1934, he was already on the train which would take him into exile when Orbeli arrived at Leningrad’s Moscow Station with papers for his release and took him off it. Rearrested in November 1938, probably on account of his family’s German origin, Derviz was charged with participation in a counterrevolutionary plot. This case was also dropped and he was released in April 1939, but he had been beaten so severely in prison that his lungs were permanently damaged. He was an invalid from then on. In 1941, when the Hermitage treasures were being packed for evacuation, he was very ill but insisted on being taken to the museum to see the Alexander Nevsky sarcophagus, the world’s grandest silver monument, for one last time. He died in 1942 during the siege.

The war brought Stalin’s purges to a temporary close and they never regained the universal character of the 1930s. Nevertheless, the post-war years saw a paranoid tightening of ideology in every field and persecution of deviant artists, writers and scholars. Stalin had always feared the independence of the people of Leningrad and in 1948 he launched a savage purge of the Leningrad Party organisation. All the leading officials in the Leningrad region were arrested and executed, as were several hundred of their subordinates. A mass arrest of the Leningrad intelligentsia, particularly university staff, followed. This time most of the ‘enemies of the people’ were categorised as cosmopolitans and Jews.

Matvey Gukovsky, a professor of Renaissance history at the university, an expert on Leonardo and a deputy director of the Hermitage, qualified on both counts. He was arrested while on holiday with friends in the Caucasus. As visitors, they were required to register with the police. Gukovsky was arrested and his friends released. In August 1950 he was sentenced to ten years in the camps for ‘counterrevolutionary propaganda’. Luckily for him, Stalin died in March 1953 and shortly afterwards all sentences were reduced by half. He was released on 11 January 1955 and started writing angry letters to the prosecutor’s office asking what he had been accused of. In November 1956 he was told that the charges against him had been dropped for lack of evidence. His rehabilitation followed, after which he became director of the Hermitage library.

Lev Gumilev, a brilliant geographer and historian, joined the staff of the library in the same year. Artamonov, who was by then director of the museum, went out of his way to recruit scholars who had suffered at the hands of the KGB and took on Gumilev to help with his research on the Khazars.

Gumilev was an extreme case. He was the son of two of Russia’s best-loved poets. His father Nikolay Gumilev was executed in 1921. His mother Anna Akhmatova survived, though her lyrical poetry was hardly published in the 1930s and fell under Stalin’s particular disfavour in the post-war years. It was criticised as ‘imbued with the spirit of pessimism, decadence … and bourgeois-aristocratic aestheticism’.

Lev Gumilev was under a shadow from the start. He was not allowed into the university on account of his social origin. This ban was lifted in 1934 but he was arrested in 1935 and not allowed back into the university when he got out of prison. Rearrested in 1938, he spent five years in custody, coming out just in time to join the army and fight in Germany. After the war, when he could have hoped for a period of peace, his mother’s political disgrace was extended to include him. In 1949 he was rearrested and sentenced to ten years in the camps. Then, like Gukovsky, he was let out after serving five years and came to work for the Hermitage. Artamonov and the Hermitage launched his new career. He became one of Russia’s most popular scholars with an array of published works. He had a vast TV and radio audience hanging on his words after perestroika and died a natural death in 1994.

A watercolour view of Palace Square, with the Alexander column in the foreground and the Winter Palace beyond, by Vasily Semenovich Sadovnikov.

The Jordan Staircase, also known as the Ambassadors’ Staircase, painted by Konstantin Andreevich Ukhtomsky after its complete restoration by Stasov following the 1837 fire in the Winter Palace. Bartolomeo Rastrelli’s exuberant Baroque design was retained with a few restraining touches – the pillars turned from pink to grey.

The Rotunda which linked the state rooms to the private apartments of the imperial family, depicted in 1862 by Eduard Petrovich Hau. It was here that Boris Borisovich Piotrovsky used to meet Andrey Borisov by night during the siege of Leningrad to exchange knowledge that both believed might be lost to humanity if they were to starve to death.

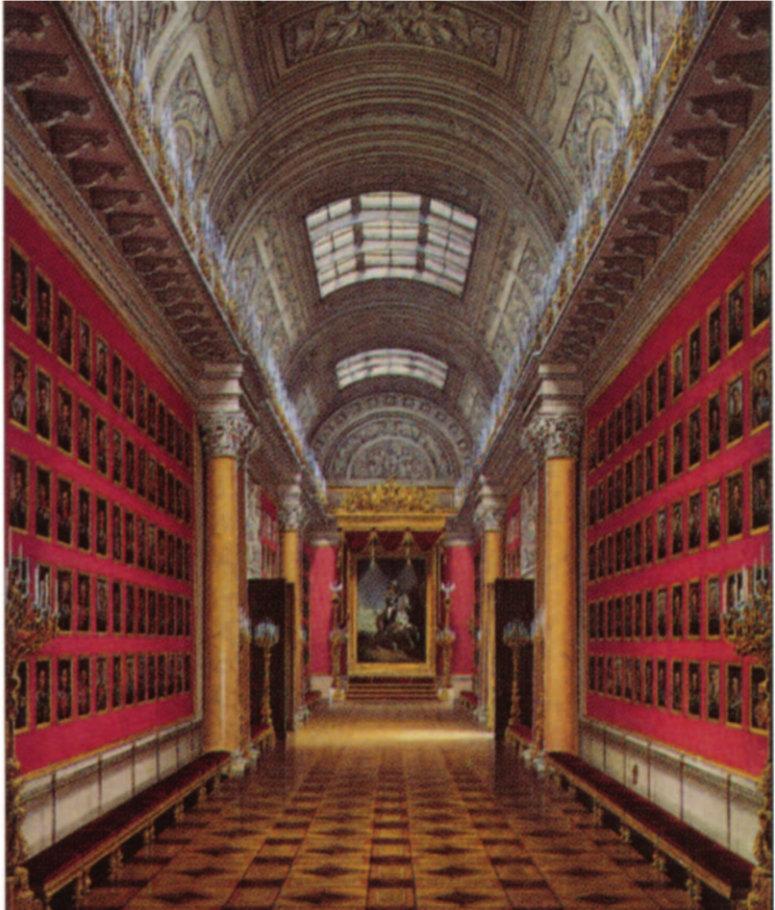

The Gallery of 1812 by Eduard Petrovich Hau, watercolour, 1862. The gallery contains 332 portraits of generals who fought Napoleon.

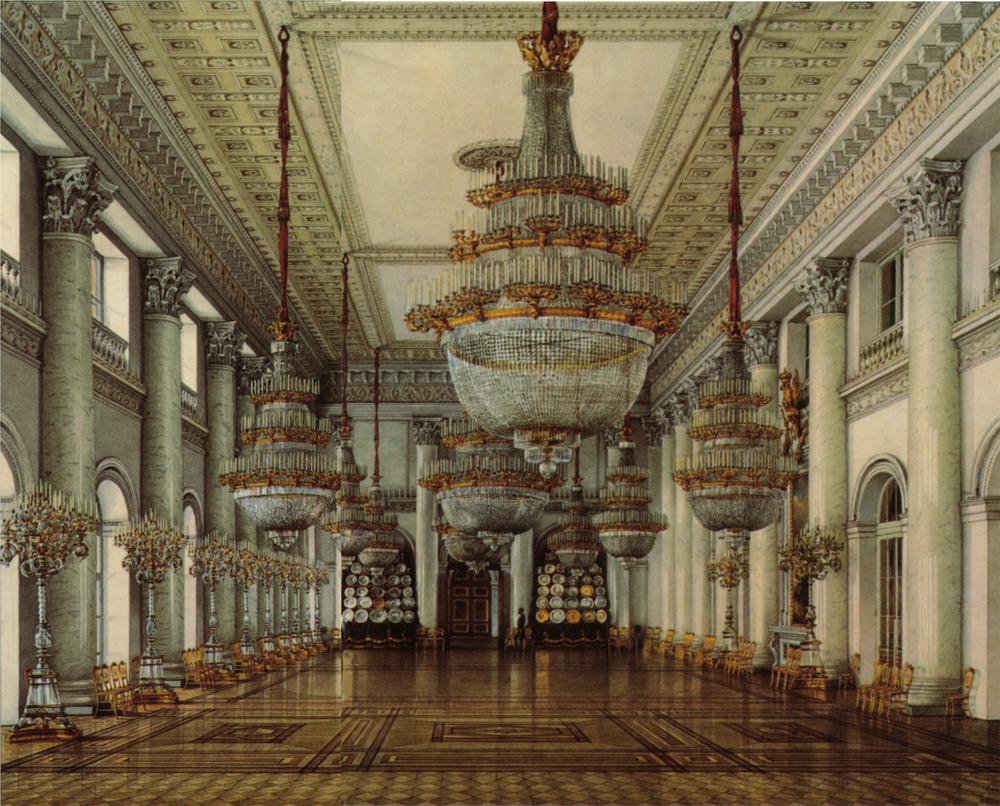

The Nicholas Hall, the largest room in the palace, depicted by Konstantin Andreevich Ukhtomsky in 1866. It was known as the Great Hall and had a floor space of 1,103 sq m. In 1855 an immense equestrian portrait of Nicholas I by Franz Krüger was hung in the centre and the room was renamed in memory of the recently deceased Tsar.

The small study of Tsar Nicholas I, a ground floor apartment favoured by the tsar who set great store by simplicity. He died on the iron camp bed shown in the foreground on 2 March 1855 and the room was left untouched as a memorial until the Revolution. It is seen here in a watercolour by Konstantin Andreevich Ukhtomsky.

The White Drawing Room, designed by Andrey Stakenschneider, depicted by Eduard Petrovich Hau in 1860.

The Military Library of Tsar Alexander II, depicted in 1871 by Eduard Petrovich Hau.