Boris Piotrovsky initially refused to follow Artamonov as director of the Hermitage. In the highly charged atmosphere surrounding the sacking, no man of honour could happily have taken over Artamonov’s chair. Piotrovsky refused repeatedly for over a month, as more and more senior figures in the Communist Party pressed him to take it on. His son, Mikhail Borisovich, says it was a very hard decision: ‘I was one of the people who told him he mustn’t take it.’ His misgivings and excuses finally drove the Minister of Culture, Ekaterina Furtseva, into a fury. ‘What else have I got to do to make you take over?’ she screamed at him.

Someone had to run the Hermitage and there was an ever-present danger that a Party hack, rather than a scholar, would be appointed. Artamonov himself supported Piotrovsky’s appointment and, despite his removal as director of the Hermitage, Artamonov was still a force to be reckoned with. He retained, until his death in 1972, the professorial chair of archaeology at Leningrad University where he was a much-loved teacher.

Piotrovsky was the obvious choice. He had been Orbeli’s deputy director and continued in the job for two years under Artamonov, only resigning in 1953 when, to his astonishment, he was appointed director of the Institute of the History of Material Culture. He had made a courageous speech praising Nikolay Marr’s work as an archaeologist at the height of Stalin’s anti-Marr campaign and, instead of being sacked, he found himself elevated to his first directorship. ‘Someone in authority must have had a hidden agenda,’ his son comments.

Piotrovsky loved the Hermitage. He had haunted it as a teenager, had helped the Egyptian specialists while a student, and worked there for over twenty years. He finally accepted the post, of which he had probably often dreamed. The sacking of Artamonov thus ushered in the dynastic era of the Piotrovsky family. Boris Borisovich Piotrovsky was director of the Hermitage from 1964 to his death in 1990 and his son Mikhail Borisovich, the current director, appointed in 1992, looks set for another long run.

It is quite as unusual in Russia, as it is in the West, for a son to succeed his father as director of a great national institution. Moreover, the two Piotrovskys were appointed for diametrically opposite reasons. Boris Piotrovsky, who joined the Communist Party in 1945, was selected as a safe man for the job at the opening of the repressive Brezhnev era, while his son Mikhail was appointed by Egor Gaidar, Boris Yeltsin’s short-lived reformist prime minister, because he was a dynamic, cosmopolitan scholar who looked capable of steering the museum through the rough water of perestroika.

Superficially, they could hardly be more different. Boris Borisovich was tall, patrician, full of friendly chat and an appeaser; Mikhail Borisovich is small, modest, with an irrepressible sense of humour and an iron will. However, there is no question in the Piotrovsky family of a rebellious son in conflict with a harshly conservative father. The two of them were obviously devoted to each other, shared most of their attitudes to culture and politics and were always mutually supportive. Rather, they provide a fascinating example of a family traditionally devoted to the service of its country – irrespective of the regime in power.

The Piotrovsky family was of Polish origin but settled in Russia around the seventeenth or eighteenth century where it was numbered amongst the minor nobility. Both of Boris Piotrovsky’s grandfathers were generals in the tsar’s army; his father, a mathematician and soldier, ran a school for the orphans who roamed the streets of St Petersburg in the wake of the Revolution, before joining the staff of the Pedagogical Institute – thus earning Boris Borisovich a free university education. Following the family tradition of service to the State, Boris Borisovich became a symbol and propagandist of Soviet culture while Mikhail Borisovich, who speaks eleven languages, ensures international support for the Hermitage.

The chameleon nature of the Piotrovsky clan is not without its critics. ‘Boris Borisovich was an old fox who always knew which side his bread was buttered’, or he ‘was a good man who only did the evil that was necessary’; ‘Mikhail Borisovich’s internationalism is only skin deep – scratch him and you’ll find a Soviet apparatchik’, etc. No one who holds power over other people’s lives can escape criticism. However, the two Piotrovskys have clearly served the Hermitage with diligence, honesty and a fierce love. ‘It may sound pretentious,’ says Mikhail Borisovich, ‘but I think we have always known that the Hermitage is bigger than those who work for it.’ Most of the Hermitage staff feel the same way. They like to call themselves ermitazhniki (‘Hermitageniks’), wryly implying that their devotion to the museum borders on lunacy.

The story of the Piotrovskys and the museum also upsets conventional Western attitudes to Russia – dissidents good, Communists bad; opening to the West good, residual Communism bad, etc. Both were active members of the Communist Party; Mikhail Borisovich ran the Party bureau at the Institute of Oriental Studies until the Party itself was scrapped in 1991. ‘The Party went out of me, rather than me out of the Party,’ he says. Boris Borisovich died of a stroke brought on by the early struggles of perestroika – the museum staff formed themselves into a Workers’ Collective which challenged the administration and demanded the right to rule. He was hurried to hospital after a stormy meeting of the Collective in the courtyard of the Winter Palace, arguing over the nomination of his successor. His son is the first to admit that it was easier to run the museum under Communism, as he battles to force the government to honour its budgetary undertakings – often without success. However, he is a man who enjoys challenges and prefers the new era.

Boris Borisovich’s widow, Ripsime Mikhailovna, recalled: ‘Boris Borisovich and I joined the Party together in 1945. It was a matter of idealism.’ The Soviet Union and its Communist Party had just won the Great Patriotic War and saved the world from Hitler’s fanaticism, or so it would have seemed to the young couple. That the Soviet Union had received assistance from its allies would have looked unimportant when viewed from within the vast territories of the country itself; the sheer size of Russia is very important in imparting a sense of greatness to its patriots. Mikhail Borisovich echoes his parents’ attitude: ‘I joined the Party out of romantic patriotism: I was working in the Yemen just after their Revolution and felt I was experiencing the kind of idealistic, political ferment I had so often read about existing in Russia in 1917. It gave me a proud sense of how Russia had shown the way and could now help struggling countries like the Yemen – it was the romance of imperialism, if you like.’

He gives a deprecating smile and a little glint from behind his spectacles. ‘It hasn’t turned out how I dreamed as a young man. Now all my friends in the Yemen are trying to kill each other – and I can’t turn on the heating in the museum because the Russian government won’t pay the bill.’ Which doesn’t mean he has changed heart or lost faith. ‘I still believe in socialist ideals,’ he says, ‘but we live with a new reality.’ His widowed mother is even more emphatic. ‘Of course I am still a Communist. What is happening is a tragedy. But I like to think that Russia, just like a building, is going through a period of restoration – that’s why it’s so uncomfortable to live in. It will be alright again once the work is completed.’

The Piotrovskys were not like the fanatical Communists portrayed in Western literature. Boris Borisovich made a personal contribution to the world of samizdat (illegal, unofficial publications) by teaching himself to visually memorise books which he could then repeat to his friends. He astounded Thomas Hoving, director of New York’s Metropolitan Museum, in the 1970s by his ability to quote from Harrison Salisbury’s Siege of Leningrad – the book was banned in Russia on account of its references to cannibalism.

Mikhail Borisovich explains that they had no anti-American feelings in the 1960s and 1970s, despite the barrage of propaganda. ‘We always understood that Americans had liberty and the good life. Everyone knew that capitalism provided better material possibilities.’ They knew it from books. His reading, he says, included Agatha Christie, Tennessee Williams, Micky Spillane, Henry Miller, Ian Fleming and Jack Kerouac, ‘books that visitors had left behind in Russia which got passed from hand to hand or traded on the black market – most of them were banned.’ The Piotrovsky family has dominated life at the Hermitage for so long that it is worth taking a closer look at them.

Boris Borisovich Piotrovsky was born in St Petersburg in 1908 but at the time of the Revolution his father was teaching in a military college in Orenburg in Kazakstan. In November 1917 the nine-year-old Boris celebrated the Revolution in the streets of Orenburg wearing red armbands; then the city was taken by the Whites, then by the Reds, then the Whites again. His schooling was interrupted, and took an original slant when the family returned to St Petersburg in 1921 to live in the Grand Hotel Europe. His father was running a school for orphans there which Boris duly attended.

At the time, many teachers spent the summer in Pavlovsk, the village associated with Paul I’s great palace, where food was marginally more accessible than in the capital and it was there, over breakfast with one of his friends, that Boris Borisovich first met Nataliya Flittner, keeper of Egyptian art at the Hermitage. She would bring small figurines – ushabti – home to show the two boys and Boris Borisovich’s imagination was fired. In the summer of 1922, at the age of fourteen, he bought his first book on Egypt. Flittner mounted a tour of the Hermitage collection for his class and he became a regular, unofficial helper in her department. The connection continued after he entered the university in 1925; while still a student he provided the illustrations for Flittner’s 1929 guide to the Egyptian collection.

Having studied archaeology at Leningrad University, he entered Marr’s Academy of the History of Material Culture as a graduate student in 1929 where he met the future director of the Hermitage, Iosif Orbeli. The patronage of two great cultural figures of the period, Marr and Orbeli, gave Boris Borisovich a flying start. He joined the Hermitage staff in 1931 without severing his links with the Academy and became the curator and researcher responsible for the art of the Transcaucasus, concentrating especially on Urartu. Having shared with Orbeli the sufferings of the siege of Leningrad and evacuation to Armenia, he became his deputy in the post-war years.

It was in Armenia that Boris Borisovich found his wife and the family’s Armenian connection has become an important facet of its character – adding a dash of southern temperament, family (‘clan’) loyalty and independence. Ripsime Mikhailovna was also an archaeologist and was working in the History Museum of Yerevan when Orbeli found her and invited her to spend two months in the Hermitage to study the operation of the museum. She became friendly with Boris Borisovich and worked on his pre-war digs at Karmir-Blur from 1939 to 1941. He used to refer to her as ‘the best artefact I found in my excavations’. Their friendship only ripened into romance, however, after Boris Borisovich was evacuated to Yerevan in 1942. Ripsime was small, pretty and full of temperament. Boris Borisovich, the tall, patrician northerner was the perfect foil. They were married in February 1944 and brought the present director of the Hermitage into the world in December.

Yerevan was to play a key role in the upbringing of Mikhail Borisovich. For two or three months in the summer his parents would decamp to the south to work on their – separate – digs. Ripsime was a medievalist and excavated at Dvin while Boris Borisovich continued to work at Karmir-Blur. Their two sons were parked with Ripsime’s parents and ran wild around the back yards of Yerevan. The doting grandparents, however, provided them with as cultured a background as they had at home in St Petersburg. Like the Piotrovskys, Ripsime’s family had belonged to the upper echelons of society before the Revolution. Though Armenian, the family lived in Nahichevan, now an autonomous region within Azerbaijan, where they had made a large fortune from running salt mines; Ripsime’s parents escaped the 1918 Azeri massacre of Armenians by walking to Yerevan. They arrived with nothing, but struggled successfully with poverty and put all their four children through university.

Mikhail Borisovich and his brother Levon were encouraged by their parents to learn foreign languages – Armenian hardly counted, being as natural to them as Russian. Boris Borisovich considered languages as the key to an interesting life in the Soviet Union – they could open a window on a wider world. So Mikhail Borisovich and his brother –still a leading chemist – had German lessons at home before they went to school and, once they had mastered that language, moved on to English and French. Mikhail Borisovich is now also a fluent Arab speaker – he first travelled outside Russia as an interpreter. And his historical studies have required him to master several dead languages, from the ancient language of South Arabia, to Aramaic and Hebrew.

He explains his choice of specialisation with characteristic modesty. ‘I had to find a subject my father didn’t know, so I became an Arabist.’ His father returned the compliment by taking obvious pleasure in his son’s success: ‘When they hear my surname in Arab countries they ask if I’m related to Mikhail Borisovich,’ he would say with pride.

Mikhail Borisovich spent an undergraduate year at Cairo University – Colonel Nasser was friendly with the Soviet Union at the time – and it was while he was there that he came across the intellectual adventure that has shaped his scholarly life: the rediscovery of the forgotten history of Southern Arabia before the arrival of Islam in the sixth century AD. He began with the Yemen, a land of nomads, mountains and deserts which, in the 1960s, was still little changed from biblical times. In his own words, ‘we Russian Orientalists gave them back their history’. The Yemenis had just thrown out the British imperialists and embarked on a Communist reconstruction, so the country was both accessible and politically exciting for a young Russian scholar. Mikhail Borisovich spent two years teaching ancient history at the Communist Party school the Russians had set up in the Yemen to help train a new ruling cadre.

Such an opportunity would not have been available to any young Russian. It reflects the fact that the Party and the KGB smiled on the budding scholar and saw him as a ‘good thing’ for Russia. The fact that his father was an important cultural figure, well known to the Party bosses in the Kremlin, would have helped. He denies working for the KGB himself, adding with a disarming chuckle: ‘If I had worked for them, do you really think I’d tell you?’ A Russian who could speak the language and teach Yemeni history presented ‘a good face for our country’, he explains. He was one of two or three specialists who worked for the Party school but were not themselves members of the Party. ‘It was the people without qualifications who were on the KGB payroll. Of course, if anyone asked me questions about life there, or the political situation, I would answer them, whether they were from the embassy or the KGB, no matter. And when I worked as an interpreter for Russian delegations, it was part of my job to write up their reports.’

It was not politics that took him to the Yemen but a group of seventh- and eighth-century manuscripts relating to its legendary past which are spread around the libraries of the world and were virtually unstudied before he began work on them. From the second millennium BC to the coming of Islam in the sixth century, there was a rich – but largely forgotten – civilisation in Southern Arabia, complete with kingdoms, monuments and a written language. It had close links with the Babylonians and Assyrians, and Mikhail Borisovich has written its history.

The manuscripts treated legend and folklore, combining elements of history with romantic imaginings. He set about the task of distinguishing fact from fiction by comparing the legends with other contemporary documents, including the Bible – a kind of historical detective work. The resulting book had a stormy reception. ‘I was prepared for scholars to object to my finding any truth in the legends but not for the opposite objection from some literate Yemenis. They thought every word of the legends was true and banned the distribution of the book in their country.’ He also explored the trade routes of the ancient Yemen, paying special attention to the inscriptions cut into the rocks by travellers – the equivalent of today’s graffiti. Inscribed on the rocks in the ancient language used before the sixth century, they provide a living record of daily life. He also excavated at various ancient sites, collaborating with the Russian-Yemeni expedition from 1981 to 1991.

After focusing on the Yemen, Mikhail Borisovich expanded his vision to take in the rest of Arabia. He wrote an analysis of the Koran, sorting fact from fiction in the light of the known facts of ancient history, using the same methods he had applied to the Yemeni manuscripts. He has many other publications to his name.

‘When I moved to the Hermitage,’ he says, ‘it was clear that I wouldn’t have much time for scholarly work.’ In abandoning the Institute for the museum he faced an easier decision than his father. Vitali Suslov, the new director, who had been his father’s number two, invited him to join the museum staff as his deputy and designated successor. ‘I thought about the offer for two or three days. But there are some things you can’t refuse – and being director of the Hermitage is one of them,’ says Mikhail Borisovich. In July 1992, after acting as deputy director for just over a year, he came into the office on a Monday morning to find a decree signed by the prime minister, Egor Gaidar, on his desk appointing him director in Suslov’s place.

‘I went and showed it to Suslov – it hadn’t been sent to him – and the first thing he asked me was when it was supposed to go into effect. The document didn’t say, so I rang the Ministry. “You’re director now,” they told me. “Sort it out for yourself.” So Suslov and I sat down and discussed what to do.’

New statutes governing the national heritage, including how museum directors should be appointed, had just been introduced, following the closure of the Party. Gaidar used the opportunity they offered to remove Suslov who was considered to have blotted his copybook in a number of ways – notably over the Hermitage Joint Venture, of which more later. He became a consultant to the museum, the first director to relinquish his post but remain on the staff since Sergey Troinitsky.

When the Piotrovskys first took over the running of the Hermitage in 1964, it was a great, old-fashioned museum organised on strict Communist principles for the enjoyment and educational improvement of the peoples of the Soviet Union. However, the political ‘thaw’ with the West had begun and around 1970 the Kremlin realised that cultural exchanges could be used as a means of exploring new contacts abroad and establishing diplomatic links. Initially, Moscow would tell the Hermitage in which country it was anxious to improve relations. ‘We would get a telegram or telephone call,’ Vitali Suslov remembers, ‘saying it would be very good if you could arrange an exhibition in London, France or America…. The next week it would be somewhere different.’ Often the exhibition projects were linked to a state visit and many of the Hermitage exhibitions abroad were formally opened by presidents, prime ministers or other political figures.

The Hermitage would seek out a partner from among the national museums of the designated country and try to develop an idea for the exchange of art exhibitions. They always tried to get another exhibition back for each one they sent out. In almost every country an exhibition of the Shchukin and Morozov paintings was the first request. As a result, many of the exhibitions were organised jointly with the Pushkin Museum in Moscow, the owner of the other half of these great collections, and many of the foreign exhibitions that came to Russia would be shown in both cities. The development of the Hermitage’s links with the rest of the world became the keynote of Boris Borisovich’s period as director.

The first exchange exhibitions with foreign countries had begun under Artamonov – the exhibition of ‘Painting in Great Britain, 1700–1960’, sent to the Hermitage by the British Council in 1960, is still remembered as a visual eye opener – but the flowering of Russia’s international exhibition policy was guided by Boris Borisovich and his opposite number at the Pushkin Museum in Moscow, Irina Antonova. ‘Masterpieces of Modern Painting from the USSR’ were shown in Japan in 1966–7. Matisse paintings from the Shchukin and Morozov collections were shown at the Grand Palais in Paris in 1970, following exhibitions at the Hermitage and the Pushkin the previous year.

At this time ordinary Russians had no opportunity to travel abroad. So Boris Borisovich set about bringing world culture to Russia. The exhibition of Tutankhamun’s treasures from the Cairo Museum, already shown with sensational success in New York and London, arrived at the Hermitage in 1974. Boris Borisovich had negotiated that it should be paid for out of the Egyptian government’s debts to Russia. In 1975 ‘Two Pictures from the Metropolitan’ came to Leningrad and exhibitions from the Louvre and Prado followed. He also took the initiative in setting up special exhibitions for which he wrote the catalogues himself, including ‘Colombian Gold’ and ‘Out of Nigeria’, an exhibition of Benin bronzes and other sculptures.

Boris Borisovich in his role as cultural ambassador ended up visiting forty different countries. Having been denied the opportunity to travel in his youth – he was already fifty-six when he became director of the museum – these expeditions had a special significance for him. He kept diaries of all his foreign visits in which he meticulously recorded his impressions, day by day, illustrating them with spare line-drawings of the kind he used to illustrate archaeological reports – and letters to his children. The extent of his official travels is underlined by the fact that he left 133 of these diaries, ranging in date from 1964 to 1990.

Another major development of his period as director was the opening of a branch museum in the Menshikov Palace on Vasilevsky Island. Alexander Menshikov was Peter the Great’s close friend and associate, the first governor of St Petersburg. Peter had intended that the centre of his city should be concentrated on Vasilevsky Island but his subjects’ understandable preference for returning home without having to take a boat sabotaged this plan. Menshikov, however, built his own palace – the first palace that was built in the city – on the island. From the time of his disgrace, at the end of Peter’s reign, until the Revolution the confiscated building was used as an extension of the nearby officer cadet school; the Bolsheviks gave it to the university for a while but then handed it back to the army.

By the 1960s its condition was very dilapidated but the city recognised that the building itself was a historical monument of the first importance. They began its restoration in 1966 and two years later brought in the Hermitage as consultants on the history of the building. The museum began archaeological-style research on it, finding many original features, such as doors, window frames, paintwork, even a whole painted ceiling in Menshikov’s walnut-lined cabinet. As a result, the city decided to restore the building to its original eighteenth-century appearance. It was a mammoth restoration project, only completed in 1981, at which point the Hermitage was allowed to rent the building and install a display devoted to ‘Russian Culture in the First Third of the Eighteenth Century’ – Menshikov’s time. The museum was finally given the building outright in 1994.

Menshikov, like Peter himself, was a great collector. His possessions, confiscated at the time of his disgrace, entered the imperial collections but were never identified in inventories as such. Many have probably survived in the Hermitage collections and the effort to identify them on the basis of contemporary documentation is a continuing challenge to its scholarly curators. The present display, however, is mainly drawn from Menshikov’s period, rather than his own collection. Its 1981 opening came as a revelation to the citizens of St Petersburg. Peter’s own Summer Palace had led them to believe that aristocratic taste was simple at this early period. The sumptuous decoration of the Menshikov Palace has dispelled this myth.

Ritzy taste has continued to be a feature of those who govern St Petersburg right up to the present day. Grigory Romanov, the Leningrad Party Secretary in the early 1980s and one of Gorbachev’s rivals, was no exception to the rule. It was thus entirely in character when a rumour started to circulate that Romanov, in order to celebrate his daughter’s wedding with suitable pomp, had borrowed one of Catherine the Great’s dinner services from the Hermitage and broken several of the plates. Boris Borisovich denied the rumour but still it grew. And it has survived for over thirty years, so thoroughly intact that it is now generally regarded as a ‘fact’.

‘There was never any truth in it,’ says Mikhail Borisovich, ‘but the rumour was very persistent and seems to have emanated from Moscow. My father denied it many times but very high-level journalists always came back with it. I think it was deliberately invented and distributed. Romanov was not loved either by the intelligentsia of St Petersburg or the Party leaders in Moscow. He was young and ambitious, and hoped to jump into Moscow politics on the basis of working-class support in St Petersburg. He was Gorbachev’s chief rival and I think someone, maybe the KGB, must have fixed it.’

Romanov also resented Boris Borisovich’s fame as one of the nation’s leading cultural figures. There was not room in Romanov’s Leningrad for a rival figure of such stature. He sabotaged Boris Borisovich’s activities in every way he could manage and refused to speak to him about the Hermitage’s problems. At one point the clash became so acute that Boris Borisovich sent a letter of resignation from the Hermitage. However, a friend who outranked Romanov arrived from Moscow in the nick of time to rescue the situation. Romanov was forced to apologise. Boris Borisovich remained the director of the Hermitage and one of the nation’s chief cultural ambassadors.

His freedom to travel was a reflection of the ‘thaw’ in Russia’s foreign relations, but the apposite verb was definitely ‘to thaw’ rather than ‘to melt’. The Hermitage library, for instance, had three grades of books: those openly available, those only accessible to museum staff, and those restricted to senior cadres with special permission. Virtually any book published in the West, the romantic biography of Catherine the Great by Henri Troyat, for instance, was only available to senior museum staff.

The offices habitually used by foreign visitors to the Hermitage were wired up by the KGB so that every conversation could be recorded. At one point, Boris Borisovich summoned his senior staff to ask them if they would kindly keep their conversations in those rooms to a minimum in order to reduce the work load of the KGB transcribers. For several days people tried anxiously to remember what they had recently said there. Among the designated rooms was, of course, the handsome director’s office on the ground floor of the Old Hermitage, overlooking the river. The seventeenth-century Flemish tapestries on its walls provided ideal cover for listening devices.

The sound engineer of an American television crew told Mikhail Borisovich that he was picking up odd signals and asked if these devices were still active. ‘I have no idea,’ he told them. ‘They are not my microphones.’ Since then he has had his office checked and been told it’s clean. ‘But they also told me that microphones can’t be detected unless they’re switched on,’ he adds, leaving other possibilities in the air.

Boris Borisovich’s attitude to his staff’s struggles with the system was sympathetic rather than combative. An older member of staff tells the story of a brush with the KGB. After refusing to become an informer, she was, in her turn, refused permission to travel by the KGB officer who had pressed her to help him – she had been invited to a foreign seminar. Erupting in a rage into the director’s office – Boris Borisovich prided himself on keeping all three doors to his office open and being available to any member of his staff at any time – the curator demanded he help her. ‘There are two things you could do,’ he is said to have replied. ‘Either you can write a letter of complaint to the Party Bureau, or you can wait until the KGB officer is promoted and then go abroad. I would advise the latter.’

Those who were allowed to travel were very strictly vetted. Anyone with family members who had been repressed, or who had spoken too freely on the telephone – most of the office phones were tapped, often so inefficiently that you could hear heavy breathing as the listeners clicked into place – was not allowed to travel. Many of the Hermitage curators did not get abroad until after perestroika. In 1985, one young curator was reprimanded by his departmental chief for inviting an American graduate student working in the department out to coffee. She was pretty, of course. However, no unofficial contact with foreigners was permitted.

On the other hand, well-vetted Party members could drink as much vodka as they liked with well vetted foreign visitors. The official hospitality of the museum was not necessarily formal. In the 1970s and early 1980s relations with the West had become sufficiently normal for tourists to start visiting St Petersburg in large numbers. It was regarded as an exotic venue and many cultured people were prepared to suffer package tours, then the simplest way of getting there, for the sake of visiting the Hermitage. Travel restrictions within the Soviet Union had also been lifted for Russians, while subsidies kept air and rail tickets at rock bottom prices. The result was a boom in internal tourism.

Under the combined impact of foreign and local visitors, the Hermitage began to come apart at the seams. At the high point, around 1981–2, the museum had some three and a half million visitors a year; the galleries were packed and queues were known to stretch round the building and down as far as Nevsky Prospect. The imperial parquet floors, with their wonderful intricate patterns designed by eighteenth-century architects, began to be ground into dust. It became urgently apparent that something had to be done.

Whether Boris Borisovich or his deputy Vitali Suslov should be credited with responsibility for the grandiose development plan drawn up in the early 1980s to deal with the challenge of the tourist boom is a moot point. No doubt they both had a hand in it but the two men, by that time, were frequently at loggerheads. Boris Borisovich had handed some of the museum administration to Suslov when he first joined the staff and, over the years, Suslov had taken more and more into his hands – eventually, more than he had competence to handle. Boris Borisovich was already seventy-two in 1980 and eighty-two when he died in 1990. Over this final decade Suslov’s role grew in importance.

Boris Borisovich had recruited Suslov as his deputy in 1967 to replace the ageing scholar Vladimir Levinson-Lessing, who considered himself too old for the job – he died in 1972. Levinson-Lessing’s erudition and charm are borne witness to by all those who knew him, though his history of the Hermitage picture gallery, published posthumously, is his only major publication. His shortcomings as an administrator are also legendary. So it is understandable that Boris Borisovich should have looked especially for administrative qualities when seeking a new deputy.

Suslov was forty-three when he joined the Hermitage. The son of a coal-mining engineer, he was born near Vladivostok, served in the navy during the war and only began to study at Leningrad University in 1946. He wrote a dissertation on the Russian avant-garde of the 1920s, then turned to Russian painting of the Soviet period, getting his first postgraduate degree (kandidat) in 1954 but never finishing his doctorate. Hermitage curators liked to point out that he was not a scholar.

When Boris Borisovich recruited him he had been deputy director of the Russian Museum for five years: ‘I wanted to start a new life as an administrator. It was a whole new world,’ he says. As a result, the two men worked together for twenty-three years. While superficially friends, relations between them became very strained. By the last five years or so, Suslov had managed to play his cards so well that he had effective control in many areas. The staff knew that if they got a ‘yes’ from Boris Borisovich and a ‘no’ from Suslov, or vice versa, Suslov’s ruling would prevail. Meanwhile, Boris Borisovich struggled to keep the ship on course, though he was far beyond normal retirement age. According to his widow, ‘he couldn’t retire because there was no suitable successor’. A significant motivation for remaining in office was to keep Suslov out of the director’s chair.

It seems curious that Boris Borisovich felt unable to dismiss a deputy who was usurping his power and making decisions with which he did not agree. The explanation probably lies with his innate dislike of confrontation, coupled with the absolute power of the Party. Suslov was a Party member and a member of the Party Bureau for his section of the city. He thus had powerful support both inside and outside the museum. Had Boris Borisovich tried to move him, it is anyone’s guess who would have won the tussle for power; Suslov could have argued, with justification, that Boris Borisovich was too old for his job.

The grandiose development plan that the two of them dreamed up in the early 1980s was the source of many problems. The prime motive for expansion lay in having galleries so packed with visitors that the visitors themselves could not see the displays or move about freely. Since potential gallery space was being used for storage, offices and restoration studios, it was natural to want to move these elsewhere and open up new exhibition areas. The potential for new displays was vast; only some five per cent of the museum’s three million objects were on show. At the same time, contacts with Western institutions had revealed how technologically out of date the Hermitage had become – the need for temperature and humidity controls, new security systems, computerisation of inventory and so on.

The museum prepared several alternative plans for resolving its problems, which it presented to the Ministry of Culture in 1980. Essentially, the decision lay between annexing adjoining properties to the museum or building new facilities on the outskirts of town. After due assessment, discussion and many changes of mind, the national and city governments approved a development plan in 1985 which incorporated both.

It envisaged the building of a vast new complex to accommodate storage, restoration and education facilities at Staraya Derevnya, beside the big World War II cemetery on the edge of town. Building began in 1989 and the money ran out in 1991. All work was suspended from 1992 to 1999 but money was spent on making the building weatherproof. The advantage of these breaks in activity was that the museum could rethink what it wanted to do with the new building. The answer was open storage with guided tours to explore the extraordinary contents. The first building was in place for the 2003 celebration of 300 years of St Petersburg. A second building was ready for the 2014 celebrations of 250 years of the Hermitage Museum. Among the Hermitage’s birthday presents was a promise of funding for a third building to include a library and a costume museum.

The star turns are a display of carriages starting with the coronation coach ordered in Paris by Peter the Great and first used by Catherine. There is also a large space filled with furniture with a glass passage running through, dividing the European from the Russian. The Oriental section includes an embroidered tent given to Catherine the Great by the Ottoman Sultan in 1793. There is sculpture, painting, icons, archaeology … as well as new restoration facilities.

The 1985 plan also envisaged the redevelopment of Quarenghi’s theatre building to incorporate offices and restoration studios; the annexation of the apartment building next to the theatre, No. 30 Palace Embankment, and its redevelopment. The east wing of the vast General Staff Building, which faces the Winter Palace across Palace Square was also given to the Hermitage. Built by Rossi in the 1830s to house the Ministries of Finance and Foreign Affairs, it contained 800 rooms and five internal courtyards. Originally planned to be a museum of decorative arts, like the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, Piotrovsky changed his mind and has made it a museum of nineteenth- twentieth- and twenty-first-century art instead, leaving older art in the Winter Palace and giving it breathing space.

The attempts to restructure Russia’s economic system which Gorbachev called perestroika had a noisy, painful but relatively superficial effect on the Hermitage. Since government financing for the much vaunted ‘reconstruction’ of the museum began to run out in 1991 – foreign currency allocations were cancelled before rouble funding – the museum and its staff were forced to continue in their old ways, working in cramped, old fashioned offices packed into corners of the palace buildings. They continued to busily prepare foreign exhibitions of Hermitage material and mount new displays in the museum itself.

However, two of Gorbachev’s favourite schemes for revitalising the economy – joint ventures with foreign companies and workers’ control of company management – caused turmoil in the museum between 1989 and 1992. The Hermitage Joint Venture, which was forced into receivership in America in 1995 and finally tipped into oblivion in Russia by Mikhail Borisovich in the course of 1996, was organised by Suslov with a buoyant desire to keep the museum in the forefront of the nation’s economic change. ‘My father knew something was wrong and didn’t want to do it,’ comments Mikhail Borisovich, ‘but Suslov said it was a “modern” solution that would contribute a living dynamism to the Hermitage.’ Government funding for the reconstruction of the Hermitage had run out and Suslov saw the Joint Venture as a potential source of huge earnings. Boris Borisovich signed its founding charter on 26 January 1989.

On paper, the aims of the Joint Venture between the Hermitage and the American company Transatlantic Agency were admirable. Its business was to include:

the sale and distribution of products and services related to the State Hermitage Museum; buying and selling goods and services; operation of stores and businesses; registering, maintaining and defending copyrights, trademarks, trade names and patents related to the State Hermitage Museum in the Soviet Union and throughout the world; defending licences in the Soviet Union and throughout the world; offering additional tourist services directly related to the activities of the Hermitage, including trips for the staff of the State Hermitage Museum abroad for educational exchanges; the organisation of exhibitions and doing other work; operating cafeterias, restaurants and hotels called ‘The Hermitage’ and other forms of services; various forms of education; organising and operating foundations funded by The Hermitage; and all other matters including acting as agents and consultants.

Unfortunately the Joint Venture turned out to be both too ambitious and too amateur. Rather than join forces with an established American company, Suslov linked the museum with the ‘Transatlantic Agency’, a company founded by a Russian émigré called George Garkusha and his American wife, with the sole purpose of acting as a partner to the Hermitage. Garkusha had worked as a porter at the museum when he left school and was employed by the Soviet Trade Department in America after he moved there. In the various depositions he made in the course of legal disputes in America, he never revealed any other commercial experience.

What most impressed Suslov about Garkusha was that he produced a representative of the famous American magazine, National Geographic, as a third party to the deal. It was envisaged that National Geographic would publicise Hermitage exhibitions in America, help with catalogues and help fund some of the museum’s archaeological digs. However, National Geographic was never a direct party to the deal. The founding charter speaks of ‘the Transatlantic Agency in association with the National Geographic Society’ but makes no pretence that anyone other than the Transatlantic Agency was the American partner in the Joint Venture. National Geographic dropped out at a very early stage.

The museum’s financial inexperience shows up in the split they agreed for the Joint Venture’s profits. Transatlantic Agency – i.e. Mr and Mrs Garkusha – were to get 55 per cent and the Hermitage – a 200-year-old museum with 2,000 employees – 45 per cent. Garkusha was appointed managing director of the Joint Venture, which took the dangerously confusing trade name of ‘The Hermitage’. Suslov was appointed chairman of the board.

The commercial undertakings of the Joint Venture never prospered. It linked up with a Canadian firm to make high class photographic reproductions of pictures but the company closed down; it did a deal on reproducing furniture; imported antique furniture from Scandinavia to be restored at the Hermitage; took a Catherine the Great exhibition on a tour of America; and commissioned a paperback picture-book on the Hermitage from a British publisher. It was the latter deal that was the Joint Venture’s final undoing, for it failed to pay for the 100,000 copies of this book that it ordered from the British publisher, Booth Clibborn. He took them to court in America and ended up the official receiver of the Hermitage Joint Venture and some one million dollars out of pocket. With its new publishing deals, the museum is now working with Booth Clibborn directly, avoiding the use of an intermediary.

The Joint Venture’s commercial ventures in Russia included making pottery reproductions of Antique items in the Hermitage collection and running shops inside the museum, as well as a visitors’ café, a staff canteen and hot-dog stands on Palace Square. None of these undertakings ended up yielding a profit to the museum.

In its progress from Great White Hope of Western-style financial salvation to Russian-style oblivion, the Joint Venture became one of the focal points of the battle between staff and management which erupted between 1989 and 1991. This again was a direct reflection of Gorbachev’s economic reforms. His ‘Law on State Enterprises’ of 1 January 1988 encouraged the staff of state-owned enterprises to form democratically voted ‘councils of the workers’ collective’ which would help direct the enterprise and have the right to hire and fire management. The Hermitage joined the fashion and started to organise such a collective council on the initiative of the Party Bureau in 1989.

Its progress was thoroughly documented by an in-house newspaper called Panorama which began publication in July 1989 and died in October 1991, as a result of massive lethargy among the staff and the new political orientation of the country following the attempted coup of August 1991. The idea of democratic control and the opportunity to complain publicly about the bosses was an exciting novelty for Soviet citizens but it soon palled.

The head of the museum publications department, Sergey Avramenko, the son of a noted poet, had been very interested in wall newspapers in the 1960s and ran one at the Hermitage which included in-house news, poems and drawings. He lost interest in the Brezhnev years, when it was impossible to say what you thought, but he urged the Hermitage to reintroduce such a newspaper after Gorbachev proclaimed glasnost – freedom of expression. The Party bureau, however, preferred an ordinary newspaper and so Panorama, a single sheet folded in two, was born. It came out once a fortnight and had a circulation of 500.

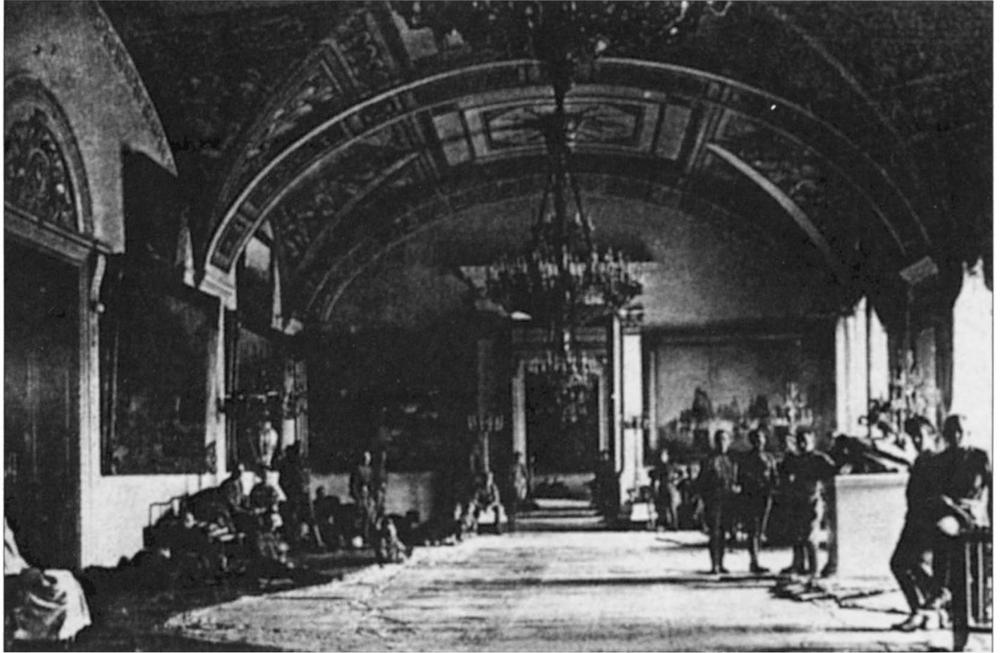

The Nicholas Hall prepared for use as a hospital ward during World War I.

The yunkers camping in the Winter Place in 1917 to defend Kerensky’s Provisional Government.

Empress Alexandra Fedorovna’s sitting-room after the storming of the Winter Place by the Bolsheviks in 1917.

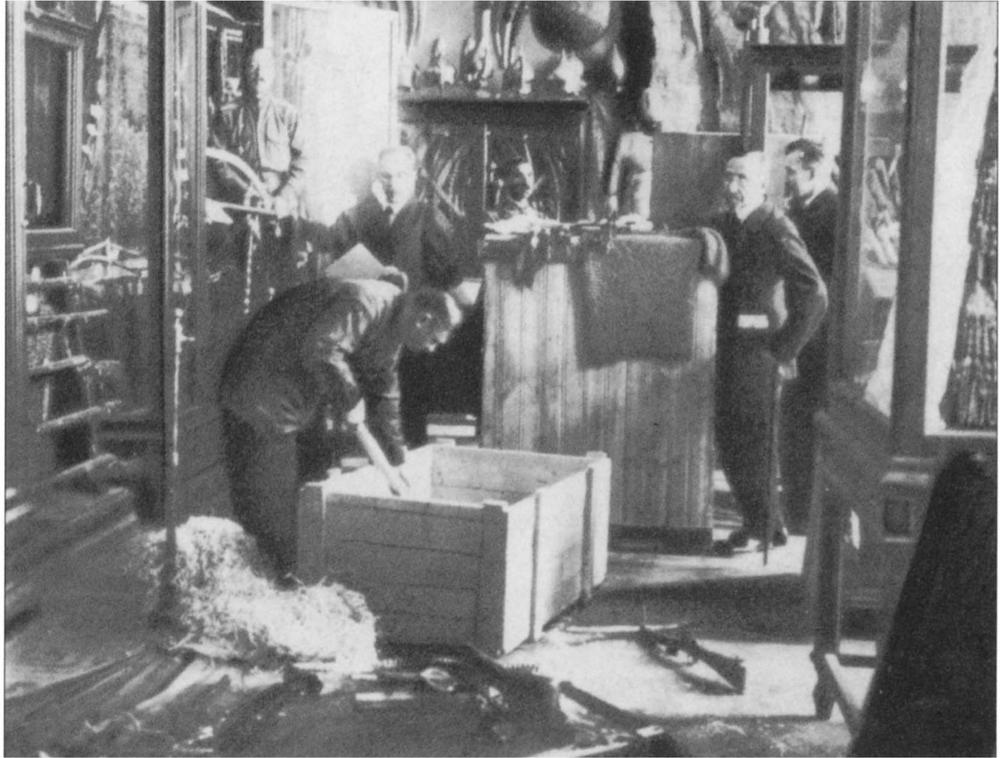

Marking boxes during preparations for the evacuation of the Hermitage collection in 1941.

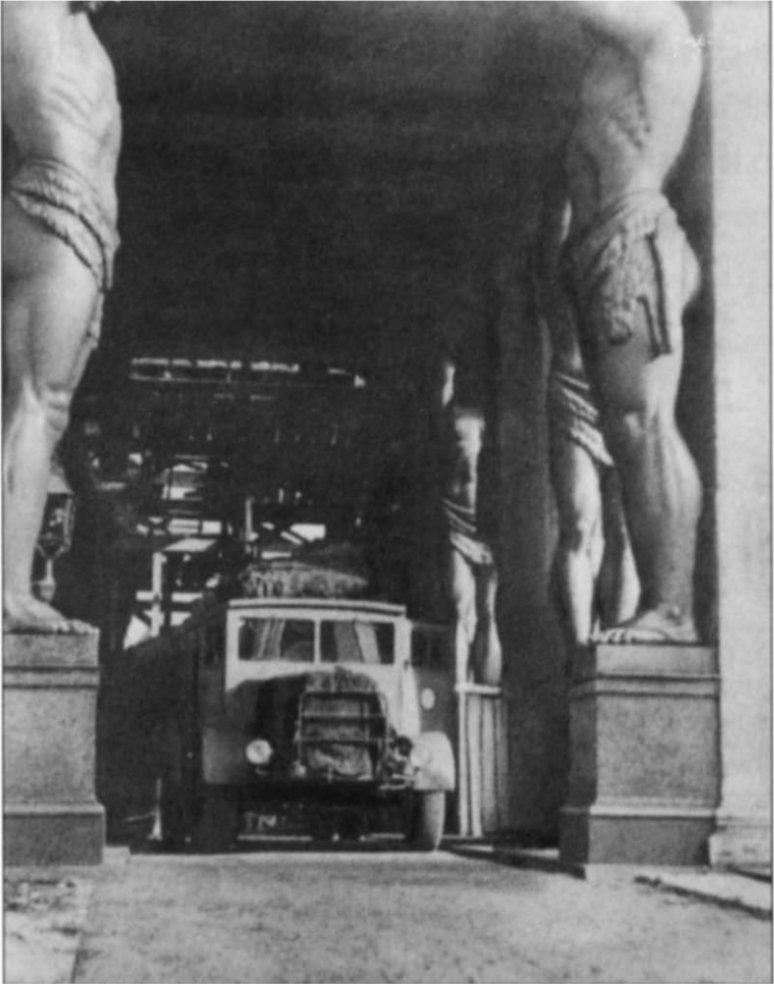

A lorry of treasures, flanked by the Atlantes, as it left the Hermitage entrance in 1941.

The effect of a 70 mm shell exploding among the coaches stored in the Riding School on the ground floor of the Small Hermitage during World War II.

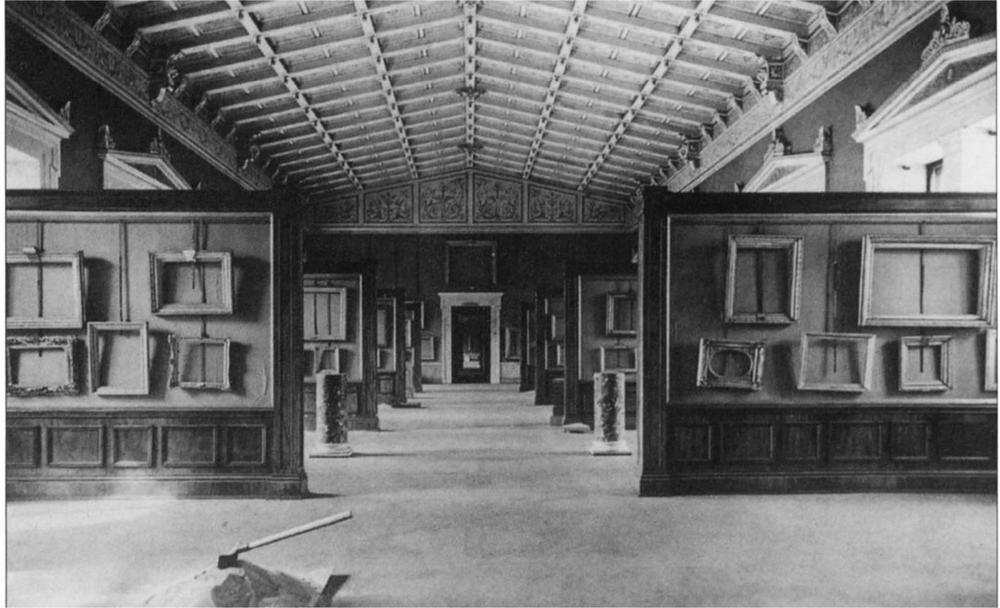

Empty frames line the walls of the gallery of Dutch seventeenth century paintings during World War II. The paintings themselves had been evacuated to Sverdlovsk. In the foreground is a pile of sand and a spade in case of fire.

The front page of the first issues announced that it was ‘The paper of the Party Bureau, Trade Union, Komsomol Committee and Director’s Office of the Hermitage Museum’ but no one was happy with such a wealth of official backing and as soon as the Workers’ Collective was up and running, in January 1990, the banner at the top of the front page was changed to read ‘The Paper of the Workers’ Collective’. The Party Bureau appointed an editorial committee of three people, Sergey Avramenko, who was not a Party member, his assistant Roald Rabinovich, and Evgeny Mavleev, the curator of Etruscan antiquities, who had recently joined the Party seeing, as he thought, an opportunity to contribute positively to change. He was to become the chairman of the Workers’ Collective but retired sadly back to his antiquities when it came to nothing, and died shortly afterwards.

It was Mavleev’s idea, or ideal, that Panorama should represent all shades of opinion within the museum. However, after so many decades of keeping quiet about what they thought, the staff of the Hermitage were understandably shy of putting their names to personal opinions in print. The most critical articles were generally written by Mavleev himself, while Rabinovich busied himself collecting the opinions that other people did not dare express and Avramenko collected poems, obituaries, letters and memories.

It became a vivid hodgepodge. The fourth issue, dated 29 August 1989, for instance, carried Suslov’s suggestions for how national laws should be changed to help museums raise funds privately, a message of special appreciation to the lady in charge of the toilets by the Jordan staircase who kept them squeaky clean and always supplied with toilet paper (‘We thank her and wish her good health’), a list of the new books in the library, an obituary, a leading article on ‘Problems about the reconstruction of the Hermitage’, a veteran’s memories of World War II and a complaint about the food in the staff canteen (‘It would be terrible if they fed us well – we’d spend all the afternoon in there. It’s so good of the Hermitage to arrange that the food is disgusting.’) One of the Joint Venture’s few positive achievements has been improving the food in the canteen.

The staffs concern about the Joint Venture and the reconstruction of the museum surfaced again and again. In November 1989 horror was expressed in Panorama at the Joint Venture’s idea of leasing the extra building on Palace Embankment, which the city council had just given the museum, to a foreign company which would ‘build a complex consisting of a first class hotel for foreign tourists (400 beds), a restaurant, a recreation zone and an administration block’ – a scheme that never got off the ground. The article explained that the building was expected to return to the Hermitage after ten years, during which time it would have made an estimated profit of ten million dollars, half of which would go to the museum. The staff were capable of seeing that this moneymaking scheme was wildly unrealistic. They would, no doubt, have expressed even greater indignation had they known that the small print of the Joint Venture agreement gave the museum only 45 per cent of the proceeds, not even half.

In issue after issue Panorama complained that the staff had been given no information on the terms of the Joint Venture agreement – although they were being asked to prepare exhibitions, make catalogues, restore furniture, etc., in its name. Another bête noire was the new air conditioning equipment that had been ordered from a Finnish company called FLEKT. The equipment had been delivered before plans were completed on how to use it; the units were large and ugly and would destroy the harmony of the rooms, and – as the porters point out – had been piled up in the courtyard habitually used for playing volleyball, thus sabotaging the museum’s sporting activities.

A whole issue was devoted to the open Party meeting held on 7 December 1989 at which Mavleev made a keynote speech vividly criticising the Joint Venture and the museum’s reconstruction plans. In his report on the meeting, Evgeny Zeimal, the Oriental Department’s expert on the ancient East, pointed out that the hotel scheme was only expected to bring in five million dollars when the overall cost of the reconstruction plans was 150 million dollars. ‘It is clearly not enough, even if we can come to terms with this lump of pus, as the hotel was described at the meeting, attached to the Hermitage (or will the Hermitage be attached to it?). The conclusion is sad. Neither the Ministry of Culture of the USSR, nor the City Government, nor the museum administration know where to get the money from for the reconstruction of the Hermitage, the first during the years of Soviet power, a reconstruction already begun.’

Zeimal also drew attention to ‘the clear lack of agreement between the activities of the director and his first deputy’ – i.e. Boris Borisovich and Suslov – ‘which has long been felt by all and which is affecting our work’. He thus flagged the battle for power, which became one of the central issues with which the Council of the Workers’ Collective concerned itself. A substantial group of staff wanted Suslov out, or at least out of the running for the directorship when Boris Borisovich should vacate his post – it was obvious to everyone that he was already too old for the job. There were a number of rival candidates for the succession. The jockeying finally became so aggressive that the Minister of Culture was invited to intervene.

A letter was sent to Nikolay Gubenko, Gorbachev’s Minister of Culture, by the more conservative departmental heads and their deputies – Suslov’s supporters – pleading for help. And when he arrived at the Hermitage to try to sort things out on 8 August 1990, the letter writers were invited to meet him, together with a token force from the Council of the Workers’ Collective. Tempers were running so high that it was impossible to get all the participants to agree the minutes of the meeting and Panorama ended up publishing an unsigned report based on a tape recording. The keynote speech had been delivered by Natalya Gorbunova from the Department of Archaeology, and repeated ‘what she had said in two previous articles in this paper, except that her criticism of the Council of the Workers’ Collective was perhaps more sharp and her praise of the director’s office, more fulsome…. At the end of her speech Gorbunova said “one gets the impression that there is a battle for power” and those present shouted “Yes! Yes!” The people sitting round the long table joyfully accused the leaders of the Workers’ Collective of trying to usurp power, without understanding that in expressing such a theory about a battle for power they were simply expressing their own interests and intentions.’

Gubenko came down on Suslov’s side. ‘The Gubenko meeting was a defeat,’ Rabinovich says sadly. ‘I was close to the heads of department and they had all been anti-Suslov. After the Gubenko meeting, they were all pro-Suslov. They were frightened that somebody new would introduce change. I was shocked by the reactions of my friends.’ Boris Borisovich Piotrovsky died on 15 October 1990 and on 22 October Gubenko confirmed Suslov as the new director of the Hermitage. While the museum mourned, there was a pervading sense of guilt that the perestroika-style battles should have so distressed the old man that he suffered a mortal stroke. He had been mystified and horrified by what was going on. A faithful servant of the Soviet regime, he found the behaviour of the Hermitage staff outside the range of his experience.

Suslov had waited twenty-five years in the wings, a deputy looking forward to his turn in the director’s chair. Under the Soviet nomenklatura system, the successor for every important post was nominated in advance and, until the final, noisy battle for power, Suslov would have known that the succession was his. As director, he now had the right to choose his own first deputy, subject to Ministry approval. And it is an extraordinary tribute to him that he let no petty resentment of Boris Borisovich’s antagonism sway him against the best candidate. ‘There were maybe four candidates inside the Hermitage. Delegations from each department visited me and pushed their man. I knew about the conflicts between the inside candidates. For me, it was better to have a good man from outside.’ He chose Mikhail Piotrovsky.

Mikhail Borisovich’s talents were obviously suited to the job. He had never worked at the Hermitage because of his father’s position but knew it inside out. If asked when he first visited the Hermitage, his answer is ‘when I learned to walk’. With his grasp of foreign languages, he had often helped his father entertain delegations and Suslov knew him well. ‘I had often visited the family, dined there and drunk with Boris Borisovich and Misha. Maybe I had an intuition.’ Maybe he also felt safer with a Piotrovsky as a running partner; he knew the family psychology so well. Both of them assumed when the appointment was made that Mikhail Borisovich would succeed him as director, but neither of them knew that it would be so soon.

The idea that Mikhail Borisovich would make a good director of the Hermitage was not Suslov’s own. Its chief propagandist had been his father. When asked about a suitable successor, Boris Borisovich would laughingly suggest his son. He did not push the idea. He aired it and it got around. The suggestion first came from Evgeny Primakov, who became first Foreign Minister then Prime Minister under Yeltsin. He was a former head of foreign intelligence, journalist, and director of the Soviet Academy of Science’s Institute for Oriental Studies. Primakov and Mikhail Borisovich had worked together on an Islamic dictionary – Russians became suddenly interested in Islam after the invasion of Afghanistan. In response to a plea from Boris Borisovich for advice on where to find a successor, Primakov is said to have responded: ‘Try looking at home!’

It is, of course, too soon to pass judgement on his directorship. It can be said, however, that he works something like ten hours a day, seven days a week. Not only can he communicate with Westerners because of his remarkable grasp of languages, but he also charms them. No one comes out of his office without wanting to help. He is a scholar and cares about the scholarly standards of the museum’s work, but is prepared to use up his own time on administration, propaganda and travelling the globe to make influential friends for the museum. He also works indefatigably with his contacts in Moscow to tease money out of the government. With the demise of the Party and the Council of the Workers’ Collective, he wields almost autocratic power over the museum’s destiny.

In his first three years Mikhail Borisovich managed to lift government funding for the museum from three to thirteen million dollars. He pioneered the publication of accounts – hitherto treated as secret – thus revealing that he had chosen to plough back almost all the museum’s private sector earnings into salary and benefits for the staff. Government salaries were extremely low in the 1990s – an average of around £50 a month for Hermitage curators – but under Mikhail Borisovich the museum regularly paid out double, as well as providing assistance in kind, sometimes food, sometimes colour televisions and washing machines. His socialist principles are very clearly revealed. Although the museum is hugely overstaffed he does not regard slimming down as an option. ‘I don’t sack staff,’ he says, ‘though I may move them.’

The money the museum earns through operations abroad has increased sharply. At any one time, there are probably six or seven exhibitions round the world to which the Hermitage has contributed. Mikhail Borisovich takes a close interest in the scholarly quality of cataloguing for these exhibitions, as well as those mounted by the museum at home; he gets his friends abroad to help with translations for multi-language catalogues and chooses his publishers with care. He encourages scholarly seminars and conferences.

He has got the government to register the whole of the Hermitage as a ‘national treasure’. ‘Which means that if I’m asked to sell from the collection, I can say no,’ he explains. Before the 1996 presidential election, he persuaded Yeltsin to sign a decree taking the Hermitage under the special protection of the Presidency – it is the only museum with such status. The decree also stated that the Hermitage should have a special line in the National Budget, rather than receiving money through the Ministry of Culture – the Ministry had, in the past, shown a tendency to spend money earmarked for the Hermitage on other causes.

The decree promised the Hermitage that the government would pay old debts and make good current funding commitments. Some of these undertakings were fulfilled while others were not – like many election pledges. By the autumn of 1996, the battle for funding had become acute. The government announced it would only pay two-thirds of museum salaries; the museums, led by Mikhail Borisovich, threatened to close. When the Hermitage’s heating bill was not paid, Mikhail Borisovich was seen walking round the museum in a natty, navy knit scarf – for the sake of television cameras and journalists. Under his unrelenting pressure, money continued to trickle into the Hermitage coffers and the museum stayed open. The bigger the problem, the brighter the light in his eyes. He is an indefatigable fighter.