Introduction

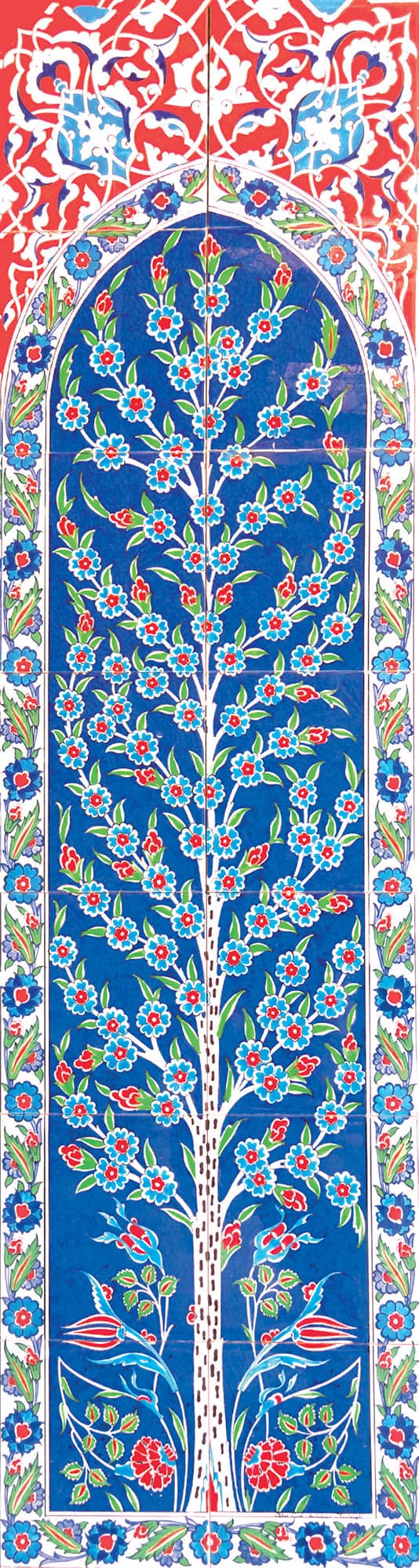

tree of life

From heart to hearth, there is a path.

—Turkish Proverb

Hoşgeldiniz. Welcome.

Two thousand years before scribes recorded the story of Adam and Eve’s arrival in the Garden of Eden, a myth was told throughout Mesopotamia of a garden where a divine tree grew whose branches marked the boundaries of paradise. A man and woman were placed there to guard the tree. In that garden, the couple had everything they needed at their fingertips, fruits and vegetables and herbs and flowers.

In Turkish, the divine tree, from which all life grows, is called Ağaç Ana, the mother tree. And with eight separate growing zones, you could say Turkey is a food-lover’s Eden. For the many faiths in Anatolia—including Zoroastrian, Judaic, Christian and Islamic—the tree of life’s abundance was transformed by the children of Adam and Eve into crops such as wheat, chickpeas, grapes and pomegranates. In a country blessed with fertile soil and water—the Tigris and Euphrates rivers originate in Turkey—when a Turk has access to even the smallest plot of land, he or she will grow everything from greens and herbs to fruit- and nut-bearing vines and trees.

It’s been more than twenty-five years since we began our journey through the kitchens and restaurants of Anatolian friends in both Turkey and the United States, friends who have lovingly shown us how to prepare dishes that not only nourish our bodies but our hearts and memories as well. We set off in search of history, culture and art, but the most tangible evidence of our great adventure is the recipes we learned along the way—the same ones we now cook every day at home.

From the forests of northern Turkey along the Black Sea where cherries and hazelnuts grow, to the Mediterranean coast where lemon, orange and walnut trees grace fields and hillsides, we have been the lucky recipients of cooking lessons in all kinds of kitchens, some impromptu demonstrations outdoors over an open fire, and others in the grand palaces of Istanbul.

We can’t imagine a better way to share these Turkish-inspired recipes than by inviting you into the kitchen. We’ll lend an apron and a knife so you can chop garlic and cucumbers for the classic yogurt sauce caçık, or mix bulgur wheat with onions, dill, basil and mint for pilaf while we prepare chicken bought from a neighbor’s farm, infusing it with cumin and preserved lemon before tucking it into the oven.

Anatolia comes from the Greek word anatolé meaning east, the land of the rising sun. Once the name of Asia Minor, today Anatolia refers to the country called Turkey, whose borders stretch from Greece and the Balkans to Armenia, Georgia, Iran, Iraq and Syria.

Aromas fill the kitchen, at once familiar and exotic: the tangy sweet scent of nar ekşisi (pomegranate molasses), hints of dried mint, lemon and Aleppo pepper mingling with pan juices of the now-golden roast chicken. We roll dough until it becomes a translucent sheet to be cut into squares for juicy lamb-stuffed manti, ravioli’s Anatolian cousin, and stir rice flour and rosewater into simmering milk until creamy pudding coats the spoon.

Our love affair with Anatolian cooking has, at first glance, an unlikely beginning. We grew up in the American Midwest—Angie in Michigan and Joy in Wisconsin—cooking at the knees of grandmothers, mothers and aunts. The dishes these women prepared when family and neighbors gathered for Sunday dinners and holidays—often with vegetables grown in their own gardens, eggs and milk delivered to their doors and roasts from the local butcher—became a connection to the “old world” of Europe. In an era when children were still expected to be seen and not heard, we listened, absorbing accents and dialects, hearing family stories and learning recipes retold through the generations.

We left the Midwest in our teens. Angie moved to southern California, where the light, landscape and flavors of a Mediterranean climate—lemon, olive oil, bay leaf and oregano—captivated her. Joy and her family moved east to New Jersey. There, she met a friend whose Greek mother’s family had emigrated from the Princes’ Islands in Istanbul and who introduced her to herb-infused roast lamb and flaky baklava.

We like to call it kismet—our destiny—when, through a mutual friend, we met for the first time in 1997 on the balcony of a pension in Kalkan, a village on Turkey’s Turquoise Coast. As the setting sun turned the sea rose-pink, we—Joy, a journalist, married with a daughter, and Angie, single, a travel writer and bookstore owner—drank wine from Çanakkale (Gallipoli), bonding over a shared passion for adventure, travel and local foodways.

Elinize Sağlik

“Health to your hands,” a wish bestowed upon one’s host, with the hope that they will invite you back into the warmth of their home.

We’d both fallen in love with the social aspect of Turkish dining, where, in restaurants, kitchens and at dinner tables, the ingredients of a dish and its provenance are an important part of the conversation, and a dish’s nuanced flavors are discussed as vigorously as the latest political scandal.

Through those lively debates, we began to see connections between familiar foods and those that took us by surprise. For instance, we learned how red chili peppers journeyed from the Americas with Spanish and Portuguese explorers and took root in Ottoman Anatolia to become Aleppo pepper, one of the world’s great spices, which takes its name from the city in what is today Syria. We had always planned to visit Aleppo’s medieval spice markets, but now, trusting in the resilience of the Syrian people, we can only hope for peace to return to the region and for the cherished pepper plants to grow again in the fields.

In glorious Istanbul, we embraced meze culture: the gathering of friends in bars and cafes over appetizers—crisp börek filled with spinach; plump marinated olives; creamy eggplant dip; slices of white cheese and ripe melon—served with thimbles of the anise-flavored spirit called rakı to stimulate appetite and conversation.

You could say we traveled across Turkey kitchen by kitchen and returned home with well-worn backpacks and notebooks full of recipes from people whose faces we will never forget. In fact, our own kitchens became a refuge during the years we wrote our memoir, Anatolian Days & Nights: A Love Affair with Turkey, Land of Dervishes, Goddesses, and Saints. Often the keenest insights would come while one of us prepared a shepherd’s salad, lentil soup or kebabs after a long day of writing.

We’ve adapted many of these recipes brought home as souvenirs of our Anatolian journeys to make them a bit more streamlined, and to use available ingredients whenever possible. But we also encourage you to try the more detailed recipes, since they can be broken down into make-ahead steps. Better yet, invite people to cook with you and your pleasure will multiply as the kitchen fills with talk and laughter and even a tear or two—maybe from the onions, or maybe not.

Preparation becomes celebration with friends peeling eggplants for a traditional casserole or marinating lamb chops in pomegranate essence. The atmosphere warms as meat sizzles in fragrant juices and we spoon marinated olives into a bowl, setting them beside an Anatolian-inspired version of classic gougères, or pâte à choux cheese puffs, made with feta and flecked with mint, nigella seeds and Aleppo pepper. They’re a touchstone from childhood when our mothers cooked their way through Julia Child, but we’ve made them our own with spices encountered on our grand adventure.

Gougères are best enjoyed when still warm from the oven, so … Hanging up our aprons, we pour ourselves thimbles of rakı. “Şerefe, cheers,” we say, clinking glasses.

Welcome to our kitchens.