I DIDN’T GET TO IRELAND, the land of my parents, until I was 30 years old. Apart from my Aunt Catherine, who helped Mum with Sue and me in London when we were very small, growing up in New Zealand, none of the Scott children ever met a single relative. It was as if our family had arrived in the Manawatū from another galaxy. We had no cousins, no aunties, no uncles, no sisters-in-law, no brothers-in-law and no grandmothers or grandfathers. It was just us—a small microclimate of Irish lunacy set in the dull and sober Manawatū landscape.

The only evidence of a wider family came from Mum’s side—fuzzy photographs smaller than postcards, with a pinking-shear trim. People not much more than white dots for faces and black and grey splotches for clothes pose en masse on a mailman’s dray or stand singly with a favourite dairy cow. Very Borat. A tall, gaunt man, splay-footed like Charlie Chaplin, with high cheekbones, cigarette in his mouth, wearing a rumpled suit, pullover and tie and a broad cloth cap on his head, was Mum’s father, Michael Ronayne. ‘Kindness itself’ is how she described him. He picked her wildflowers, sang her songs and carried her on his shoulders along the banks of the Blackwater that flowed slow, deep and wide past their thatched cottage. White swans trailed silver wakes amongst golden reeds on their side. Castles and grand mansions half hidden in forests of Sherwood green rose up on the other.

Unlike Mum, our father never spoke of his family. The closest he came to acknowledging kith and kin of any sort was when declaring bitterly that our mother’s brothers were thugs who deserved go to prison for assault and battery. He didn’t elaborate, but it was clear he had been on the receiving end of some sort of thumping. He didn’t celebrate birthdays or acknowledge anniversaries—though, to be fair, two years after I had been accredited University Entrance, he appeared in the living room one evening and chucked a watch in my direction, slurring, ‘That’s for passing University Entrance, Egghead.’ Until very recently I had no idea he had two sisters, who visited Mum in London after Sue and I were born and were very kind to her.

Having no connection with the past is curiously liberating. I have no heritage defining or confining me. No family tree determining how far the fruit can fall. I grew up believing I was a blank cheque and I could fill in as many zeroes as I wanted, this number varying widely as my self-esteem waxed and waned.

The Māori concept of whakapapa has no meaning for me. As a political reporter, on numerous campaign trails I accompanied party leaders onto many marae in chilly weather. The welcomes were always elaborate and the protocols always strictly observed. This often meant standing in drizzle for hours or sitting on hard benches in drizzle for hours, as dignified elders on the edge of tears paid interminable homage to ancestors represented in beautiful carvings on the walls and ceilings. When I wasn’t fretting about frostbite or deep-vein thrombosis I marvelled at their obsession with people and things that went before.

I did wonder if whakapapa would have more relevance and make more sense to me on my first visit to Ireland in 1977. I pondered this and other things as I stood on the deck of the rail ferry taking me across a lumpy Irish Sea—aluminium-saucepan grey flecked with mashed-potato foam, a portent of the national dish slapped in front of me every night for the next week. Swimming in molten butter, it was usually accompanied by the strict instruction, ‘Work away, boy. Ye must be famished! Work away!’ Only the Irish treat eating like a weights session at the gym, where you push your body to the absolute limit, eating until you can’t take another bite, but do anyway. It must be a genetic memory from the potato famine.

THE TRIP TO IRELAND WAS one I very nearly didn’t make. After six months in England and France, I just wanted to hightail it back to New Zealand. Spring refused to arrive, daffodils refused to flower, robins refused to sing, snow refused to melt. The family had already departed and I was left desperately circling Australia House on the Strand in a badly dinged Commer campervan that I hoped to sell to another poor sucker like me. Ahead of me and behind me, a convoy of homesick Aussies and Kiwis in similarly dented VW Kombi vans were hoping to do the same, all of us shooed away like seagulls at an airport by aggressive policemen every time we threatened to settle. In the end I sold the lumbering lemon to a sweet middle-aged English couple on Hampstead Heath, who told me apologetically that it was a buyers’ market and they had me over a barrel. Had they actually sodomised me I seriously doubt that it could have hurt more.

I spent some of the pitifully small bundle of notes on the train fare back to the Georgian manor with a gatehouse in rural Sussex which was the residence of my de-facto in-laws, the only people I have ever heard shout ‘DON’T COME FOR LUNCH!’ down a phone line when friends rang to say they were contemplating a spin in the countryside. That night I rang my sister Jane in Palmerston North—Mum was living in her tiny sunroom—to tell them I wouldn’t be heading to Ireland this trip due to my straitened circumstances. Mum worked in a shirt factory and Jane was a talented artist living off the smell of an oily rag, albeit paint-splattered. Somehow they telexed me £160. How could I refuse them? I boarded the boat-train at Paddington filled with gratitude and not a little apprehension.

I’m glad I went, if only to confirm beyond all reasonable doubt that I was a New Zealander and didn’t belong anywhere else. The magical, mystical land of my forebears proved to be neither.

Not that my welcome wasn’t warm and my relatives weren’t lovely. Cousin Richard picked me up from Cork station and drove me to Fermoy in his battered VW, through a landscape almost violently green. The main crop seemed to be Celtic crosses made of stone and the predominant livestock white horses so still they could have been hewed from the same rock. We pulled up outside Daly’s store in High Street, opposite a handsome stone bridge with multiple arches and a rushing weir. This weir was where my grandmother’s first husband, a publican, took a team of horses to drink when he’d had too much to drink himself, and they all drowned. On my return, my father asked me if Daly’s store still smelled, in the great Irish tradition, of stale bacon and kerosene. It did. I was rushed behind the counter to a small lounge out the back where aunts, uncles and cousins were waiting; I was hugged and squeezed and bombarded with scores of questions about Mum. Auntie Chris, Mum’s half-sister, kept exclaiming in high excitement, ‘Dis is Joan’s boy! Isn’t he gorgeous, girls! Couldn’t ye just eat him?’

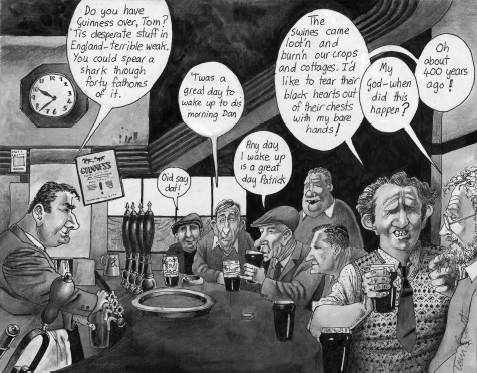

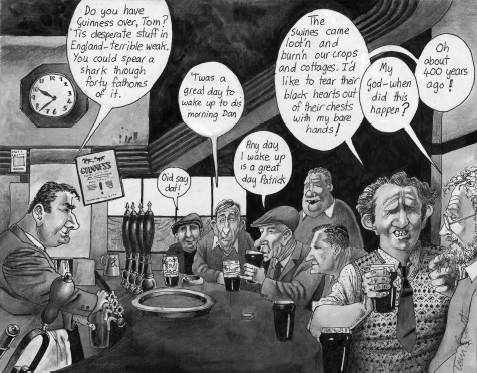

For the next week, I was the prize in pass-the-parcel. Rushed hither and thither, from village to village, cottage to cottage, pub to pub, drinking pint after pint of Guinness until two in the morning, then lying down gingerly on rock-hard beds before pitching into a soothing, Guinness-tinged abyss. I got taken to kiss the Blarney Stone, to afternoon tea with chirpy Uncle Tom and his elegant wife in their grandly furnished quarters above their antiques shop in Fermoy, and to call in on sweet and subdued Uncle Bonnie and Aunt Queenie in their almost bare, terrace house in Aglish. It was empty of furniture because their angelic-looking boy with the eyes of a captured feral creature, who couldn’t speak, was given to breaking things in a rage. Later in the pub next door he poured soft drink over his mother’s head. ‘Isn’t he a beautiful boy, Tom?’ Queenie asked me keenly, while Bonnie smiled a sad, weary smile. When my mum returned to Ireland she took Michael for long, rambling walks. She made a connection with him and he was as sweet as a kitten for her. When it was time for her return to New Zealand they both bawled their eyes out.

The thatched cottage on the edge of the Blackwater with the wild roses tumbling madly over the roof was what I wanted to see most. In the middle of the day Uncle Paddy, who had never married for reasons that quickly became obvious, lay fast asleep, fully dressed with his boots on under tousled, grimy sheets in the bed he’d been born in. This was the bed my mother had been born in as well. Paddy needed his sleep because most nights he and Bonnie went poaching salmon. Neither of them could swim, but they worked without lifejackets in the pitch black to avoid detection by river patrols. I declined their invitation to join them. In the morning, he lamented the size of the fish, declaring his support for stiffer penalties for poaching. I went with him in his battered Mini by back roads—to avoid the Garda—to the poultry factory. By law all fish in the river were the property of the British aristocrats and German industrialists who owned the castles and estates running down to the water’s edge. Justice of sorts was served when the same people paid a fortune for Paddy’s salmon when it was served up to them in fancy London restaurants. Clearly the Irish tribes could do with some dignified elders of their own demanding that their ancestors be honoured and their ancient fishing grounds respected.

Everyone remembered Mum. She was her siblings’ favourite sister and her nieces’ and nephews’ favourite aunt. They used to run to meet her when she got off the train from Limerick, laden with presents. My cousin Anne, a lively, attractive woman, told me that Mum was a striking, glamorous, glorious force of nature. During the war, she worked as a fashion buyer for Roches department store in the centre of Limerick, a grand Victorian structure—Munster’s answer to Harrods. There is a picture of her with Katharine Hepburn tresses, dark lipstick on full lips, wearing a stylish tweed hacking jacket and smart jodhpurs, sucking on a long cigarette. You could imagine any number of earls and a Mitford sister or two just out of frame. She looks confident, poised and carefree. Then she met my father …

In a rare moment of candour he told us once that he spent the war ice-skating in Canada. Thin ice, most probably. Photos taken at this time show a snappy dresser with his arm around a different pretty girl in every picture. He resembles a youthful Bill Clinton. His wavy hair is slicked back with Brylcreem and parted down the middle. There is another parting between his two front teeth, which my brother Michael inherited. It turned both of their smiles into teasing, knowing alarm signals—stand clear, a joke is coming. Dressed in his RAF uniform, Dad is only truly smitten in one photo—the one where he is tenderly cradling his rifle.

He was an airframe engineer stationed in places with colourful names like Winnipeg, Moose Jaw and Medicine Hat. He got to war-ravaged Europe after hostilities had ceased, as part of the Army of Occupation in Munich. He was in a beer hall one night when some Kiwi soldiers, who wore shorts in all sorts of weather, arrived and ordered beers. Things were going well until a barman called a Māori a monkey. His voice swelling with admiration, my father described how his Pākehā mates took exception and completely wrecked the joint. When British military policemen in their distinctive helmets and white spats came running, blowing their whistles and waving long batons, the Kiwis kicked the snot out of them as well, then, as casual as you like, strolled into the bar next door and ordered another round. My father was so impressed that he decided then and there that he would join the Royal New Zealand Air Force.

Tom Scott Senior, my dad.

While waiting for his papers to come through, he helped build the Shannon airport on the outskirts of Limerick, which is where he met my mother Joan, who all for her sophisticated airs was completely unworldly in matters of the flesh. A good convent girl, everything below the neck and above the knees was as mysterious, as dangerous and as out of bounds as the Belgian Congo.

Many years later I took her to a play at Downstage Theatre in Wellington—Tonite Let’s All Make Love in London by my good friend Dean Parker, a brilliant screenwriter (Came a Hot Friday), playwright and essayist. For much of the first act, the male lead padded around barefoot and completely naked. We were seated in the front row, virtually on stage. At one point the well-endowed young man came close enough for her to check if he had an inguinal hernia or a circumcision scar, which I feared she might be doing when she leaned forward keenly. In a stage whisper, she turned to me and said, ‘I’ve only ever had your father’s penis inside me!’ Shocked gasps rippled through the auditorium. She topped this with, ‘What a shocking waste of vagina!’ We used to joke that Mum was so fertile she could get pregnant watching BBC documentaries on sperm whales. As a petite old lady with a pink rinse, sitting demurely at our dining table, surrounded by her grown children, who now had children of their own, she explained her fecundity as follows: ‘I stuffed meself with toilet paper, but your father’s sperm always got through!’ My response was to tell her that attempting to stop spermatozoa with cellulose was the equivalent of expecting a pine plantation to act as a rabbit-proof fence. I have a degree in physiology, which I felt I must put to good use. Mum sniffed. ‘Ye can’t help yerself can ye? Ye always take tings too far!’

WHEN MY FLYING VISIT TO Ireland drew to a close, an honour guard of relatives formed outside Daly’s store to wave me off. Brooking no argument, Uncle Tom pressed £50 onto me, and Chris another five, which she couldn’t afford. It was a godsend, and I never thanked them properly. I regret not writing to them.

Chugging north through empty countryside, I imagined my mother taking the very same trip 30 years earlier as an unmarried woman, her belly swelling with two unborn children percolating inside her, sitting alone, hoping not to be noticed by the nuns and priests who seem to be permanent fixtures in every Irish railway carriage. Head pressed against a cool windowpane, she would see her fretting reflection mixed in with theirs. She would be sniffling and using the sleeves of the designer jacket that would never fit her properly again as a hanky. Tears of regret and shame would be causing her carefully applied makeup to run. She would be shivering with fear, wondering what lay in store. All she knew with a fierce clarity was that no one was taking her babies off her.

This was not easy in Ireland. Unmarried mothers were subjected to enormous pressure from the church to give their babies up for adoption. Sue could easily have ended up in Canada and me in Australia. Or we could have disappeared altogether—if not off the face of the Earth, then beneath it. Recent grisly discoveries of mass graves containing the remains of babies and small children in the grounds of former Catholic nursing homes and orphanages confirm what many always half suspected. Certainly Mum knew enough to take the afternoon train to Rosslare Harbour, to cross the Irish Sea in gathering darkness, to disembark at Fishguard Harbour in the middle of the night and board another train bound for Paddington, arriving just before daybreak. Her older half-sister, Catherine, tall and beautiful, was waiting on the platform. They fell into each other’s arms, sobbing.

Catherine took generous and kind care of Mum right up until her confinement, and Mum desperately wanted me to pay her a visit before I flew home. It was the least I could do and hardly out of my way. Catherine and her husband, Herb, lived in Hounslow, below the flight path to Heathrow. Every few minutes a 747 rattled every cup and plate in the house.

She was still tall and beautiful. Mum must have mentioned in her letters that I was a cartoonist. Sensing a connection, Herb, who saw himself as something of a Bohemian in the tradition of Picasso and Chagall, rose from the table to fetch his latest oil. It was of a bull moose with huge antlers in full roar, standing in a clearing in the middle of a Canadian forest. Little islands of white unpainted canvas were dotted across it. ‘Only three numbers to go!’ he declared proudly.

Back in New Zealand I was meanly recounting this moment when Mum interrupted, demanding to know if her sister still had all her own teeth. It was more than idle curiosity on Mum’s part. Catherine had borne witness to the most degrading, stinging humiliation of Mum’s life—something she never really got over.

The winter of 1947 was the coldest on record. Freezing Arctic storms lashed the British Isles. Three years after the war London was still pock-marked with bomb craters fenced off with barbed wire and sandbags. Whole streets were missing. Frequent heavy snowfalls disguised much of the ugliness. On the rare occasions that watery sun broke through grey skies, and before the soot had a chance to settle again, London was briefly as pretty as an illustration from Dickens’ A Christmas Carol.

When Mum’s contractions gathered pace, Catherine took her to Hammersmith Hospital. I arrived first. Whenever the opportunity presented itself, and even when it didn’t, Mum reminded me that squeezing me into the world was an excruciating experience. She lost a lot of blood and doesn’t remember Sue coming out at all. Septicaemia set in. She was delirious for days, coming round to discover she had dentures, courtesy of a hospital dentist who had gone to work with pliers and done a simple Irish colleen a favour. Mum had been very proud of her teeth. She wept with grief at the loss while feeding Sue and me. Three of us in a narrow bed, all gnashing our gums.

The Magdalene home for fallen women was badly damaged in the Blitz. One end of the ward was a flapping blue tarpaulin. Mum woke many mornings with snow spilling across the stone floor. How she coped in the bitter cold in a foreign country still exhausted by the war, a big city crippled by strikes and coal shortages, with two small children, no husband, no income and no home of her own, I’ll never know.

WHEN WE WERE BIG ENOUGH she got digs of her own opposite a Jewish primary school. They advertised for a cleaner and Mum knocked tentatively on their door. Seeing twins gurgling in a pram they took pity and employed her on the spot. She claims she didn’t do much cleaning beyond pushing a sodden mop back and forth while Jewish women, some Holocaust survivors, played with Sue and me and made her cups of tea. Mum never forgot their kindness and wouldn’t let us forget it either. When the movie Exodus came out she made Sue and me cycle four miles into Feilding with her to watch it. Starring Paul Newman, it was about Jewish boat people, refugees from civilisation’s darkest chapter seeking a new homeland and being denied entry into Palestine by the Royal Navy.

Meanwhile, back in London, the streets teemed with maimed and crippled war veterans who’d helped defeat Nazi Germany. Mum’s heart filled with dread whenever one hobbled towards us, because I would imitate their mannerisms and gait with an uncanny accuracy no less hurtful for being entirely innocent. The seeds of future caricature skills were being sown long before I could hold a pen.

It was around this time that my mother’s brothers managed to track down my father. He had enlisted in the Royal New Zealand Air Force and was on the verge of boarding a boat for New Zealand on a single man’s assisted passage. His friends were appalled. ‘Two little rocks in the middle of the fucking sea! Where will ye go when the tide comes in?’ With no time to lose, Mum’s brothers manhandled him into the back of a car and delivered him to a registry office in Hammersmith, where Mum was waiting with Catherine, Sue and me. My father had been roughed up quite badly. The registrar had seen this sort of thing before and didn’t bat an eyelid. Nor did my father. He couldn’t. Both his eyes were swollen shut.

Despite this initial reluctance the briefest of honeymoons ensued, which must have gone well because affectionate letters were exchanged in the months it took to obtain the documentation necessary for us to join him. We set sail for New Zealand from Southampton in July 1949 aboard RMS Tamaroa—part of the once mighty Shaw Savill Line. Catherine came to see us off and collapsed with grief on the docks. A giant policeman lifted her over the barricade and let Mum and her sister hug one last time at the foot of the gangplank.

Mum describes the voyage as a nightmare. Sue and I were drawn continually to the rail, where sharks trailed the ship’s wake. There was a children’s party on 21 July. I know this because Mum kept the menu. Paper must have been still subject to postwar rationing because the document is barely the size of a credit card; it records poached eggs on toast, roast turkey, salad, bread and butter, preserves, cake and fruit jellies.

Steaming towards Panama there were whispers of an outbreak of lesbianism below decks. Mum thought it was a tropical disease and panicked because Sue and I hadn’t been inoculated against it.

Crossing the Equator, she bought us our first ice cream. Vibrating with excitement, I slammed the cone smack into my forehead and dropped to the steel deck in a dead faint. It was a harbinger of many not dissimilar accidents to come.

Our father somehow persuaded the skipper of the pilot boat to take him out onto the Waitemata Harbour to board the Tamaroa and surprise Mum before the ship docked in Auckland. Anticipating another 40 minutes of prep time she had no makeup on and was wearing a drab nightie; her hair was in curlers and her false teeth were in a glass by the bed.

He entered without knocking. She screamed and lunged for the teeth. I screamed as well. While my father was reeling in shock, Sue had the presence of mind to totter towards him, smiling. I hid behind Mum and shat myself. He never forgave me.