ON A CANAL-BOATING HOLIDAY IN England in the spring of 1997—the spring that never sprung—we travelled down the Grand Union Canal towards Stratford-upon-Avon on a long-boat, Brummagem Lass, at full throttle—a pace so glacial pensioners wielding Zimmer frames caught up with us easily and eventually disappeared around bends in the towpath ahead. I didn’t mind. With deep snow carpeting meadows and weeping willows draped in hoar frost, it was a world of crystalline beauty and hushed tranquillity. I half expected Ratty and Mole—well wrapped up—to come around the corner in a skiff. Glimpsing stately homes through curtains of oak and ash reminded me of something that I couldn’t quite place.

In the Bard’s place of birth it was demoralising not being able to afford tickets to the Royal Shakespeare Company’s production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Somewhat disconsolate, I took washing to a laundromat instead. Waiting for the dryer to finish I picked up a copy of Tatler and read about a gymkhana and a girl with a name something like Lady Priscilla Burke-Pounding coming first on a pony called Little Nigger Boy. I laughed out loud. And it came to me. This stretch of England reminded me of arriving in Feilding for the very first time in 1954.

We drove in from the south, up a broad boulevard lined with tall trees and grand mansions. Feilding regularly wins the title of New Zealand’s prettiest town. Before the arrival of the wrecking ball it had two magisterial picture theatres and a square lined on all four sides with exquisite two-storey colonial architecture. After Rongotea, things were looking up.

But our topdressing truck laden high with possessions didn’t slow. We kept heading north, through town out into flat countryside and a farmhouse with a rotting verandah, another copper that needed firing up, another outside toilet with a can that needed emptying, and a clothesline sharing a house paddock with moulting hens and grumpy Southdown rams with scrotums so grotesquely swollen they could barely walk.

There were no rats, but the house was a little the worse for wear. Real estate agents talk about places being tired—this place was exhausted. The linoleum in the bathroom had brown lakes in it where it had worn through to the floorboards. Mum put up with it for several years, then used free sample pots of Dulux pastels to approximate the original pattern. Unable to afford a paintbrush, she dabbed on the colours with Dad’s shaving brush. The end result looked like someone had eaten copious quantities of Frosty Jack shocking pink and lime green ice cream washed down with Blue Lagoon soft drink and then been violently sick.

Mum couldn’t afford turps either. Despite her best efforts with Sunlight soap and scalding water, the bristles of the shaving brush solidified into something approximating a lobe of diseased liver. Understandably, Dad went apeshit. I admired Mum’s strenuous denial of any involvement, despite standing on the proof.

I was recounting this tale for neighbours who lived two miles up Kimbolton Road when something immensely gratifying happened. Rosemary Ogle, a tall, sweet-natured, elegant woman, who had been laughing hysterically, suddenly exclaimed in surprise, ‘Oh my God—I’m peeing my pants!’ There can be no higher accolade.

The Ogles had a Romney stud farm with a spreading, handsome homestead, a circular driveway, a grass tennis court, and a cosy cluster of white stables, a woolshed and a barn. Their huge kitchen had a walk-in pantry and a walk-in cool room, where carcasses of lamb hung from hooks. The contrast with our place could not have been greater, and I loved being invited up there. Mrs Ogle would lean forward and ask sweetly, ‘What’s happening at home, Tommy?’ And I was off like a racehorse on starter’s orders, snitching on my family for cheap laughs, her hot scones and delicious homemade quince jam.

I told numerous stories about Sidney, Dad’s giant worker who dragged bags of slag and superphosphate to the rear of our topdressing truck and emptied them into the hopper. This was a demanding, dusty, choking job that my brother Michael and I took over on Sidney’s weekends off, which meant we developed forearms like blacksmiths well before puberty.

I told them Sidney’s personal hygiene skills were somewhat rudimentary. Like one of the witches in Macbeth, her favourite play, Mum would emerge out of the steam swirling from the wood-fired copper in the washhouse and wave a furry wooden paddle at me, dangling colossal underpants smeared in excrement. ‘Look at dis, would ye! The filthy bastard can’t wipe his arse properly!’

I also told them how Sidney was deadly with a shanghai and could shatter ceramic power-pole insulator cups from 50 yards, and how he once knocked a female possum clean out of a macrocarpa tree. Sister Sue found a bald, blind baby possum in its pouch that we brought home and fed with an eye-dropper.

The wallpaper in the kids’ bedroom hung down like Everglades moss, which the possum loved running up as it got bigger, until it reached critical mass and started stripping the paper and hessian off entirely as it climbed, exposing bare dusty sarking.

Mum, Sue and I went to work with flour-and-water paste and newspaper and relined the room, transforming it into a papier-mâché cube. When it eventually dried, I painted the walls blue, added a coral reef, bright tropical fish and a pirates’ chest spilling doubloons. My crowning touch was a large cardboard shark hanging from the ceiling. Kids up and down Kimbolton Road, who had swags of Meccano sets, Hornby trains, Enid Blyton books, Rupert annuals, dolls and dolls’ houses, abandoned them in droves to visit my undersea world.

It was the same with the submarine Micky and I built in the house paddock out of a rusting, corrugated-iron water tank that we tipped on its side. The Ogles, Hoggards and Hennigans had rubbish dumps filled with treasure at the bottom of banks at the back of their farms. Rummaging around in the bush and blackberry that lined the meandering Oroua River we came home laden with old radios, lamps, engine parts, broken Douglas chairs—just what you need in a German U-boat. Most highly prized of all was a World War One gas mask, which obviously the captain of the submarine wore in case the rest of the crew were overcome with fumes—always a risk 10,000 leagues beneath the sea. Most of the fuming came from our father: ‘Clean this shit up. It’s like a Māori pa around here!’

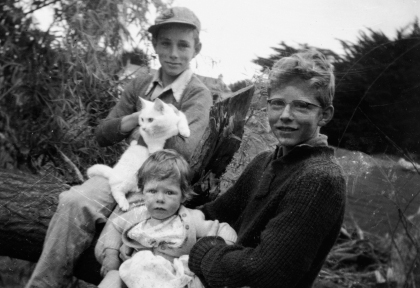

Michael, Sally and me.

STORY-TELLING DIDN’T START WITH THE Ogles. In the primers when they called for morning talks, my hand was always the first up. One Monday I was describing how I had been to the planet Mars at the weekend. The teacher sighed and gently suggested that I might be exaggerating. I pointed to the dumbest boy in the class. ‘Gary came with me, didn’t you, Gary?’ Thrilled to be included in this epic voyage into space, even if the details were of necessity somewhat hazy, Gary obligingly said yes. She gave up at this point.

I broke myself of this habit next spring when mother ducks followed by waddling trains of ducklings appeared on the Hennigans’ pond just beyond the woolshed. I got up before dawn, crept into the flax bushes and kidnapped a tiny duckling for my morning talk. I carried it home carefully and tucked it just under the rim of a sack full of potatoes in the washhouse. I would smuggle it to school in my lunchbox later. It would be a triumph. It would make me a star.

Halfway through breakfast I sneaked out to check on it. It is not by accident that the term ‘dead duck’ has entered the lexicon. I rolled back the sacking and there it was—still cute, but stiff as a board with its tiny webbed feet pointing skyward. I disposed of the body in tears and returned to the table weighed down with remorse.

We didn’t have many books at home, but we had a radio that I listened to faithfully every night after dinner right through to bedtime. After that, when a suitable interval had passed, I crept into the hall and lay on the floor next to the living-room door and listened some more to it blaring through the cracks. Often my laughter during The Goon Show gave me away, yet despite clips around the ears from my father, I was always back again the following night.

I loved knowing what was happening in the world. My favourite words were, ‘To end the news, here are the main points again …’ Most afternoons in Standard 3 we had a general knowledge quiz, which I loved. I was devastated when my classmates eventually complained that it wasn’t fair because I knew all the answers. The teacher agreed and I was banned from taking part. It was the same when it came to telling jokes. I sulked badly when I was told I had to let other kids have a turn. My twin sister Sue, normally shy and retiring, was finally able to participate.

Sue is the life and soul of every party now, a terrific painter and a very funny woman, able to tell shocking stories against herself. After her first trip overseas she freely admitted she was staggered to find in France that they didn’t speak English with a French accent. When I had finished laughing I asked her why she had thought that would be the case. ‘That’s how it is in the movies.’ Then she grinned. ‘It gets worse. When I got off the plane in Los Angeles on the way over, I was so proud that New Zealand companies like Coca-Cola, Hertz and Kellogg’s had taken over the world.’

Very few photographs were taken of us together as children. Those that do exist depict me squinting cautiously at the camera, bracing myself for something, and Sue looking dazed, her mouth slightly agape, also expecting the worst. Half in jest, she says her school days were miserable because of me. Teachers kept asking her why she wasn’t as clever as her brother Tommy. You would never tire of hearing it. I wasn’t solely to blame. She was severely traumatised by the actions of a troubled boy I’ll just call Paul, whose colossal, terrifying mother came to fetch him after school in shapeless hillbilly garments, gumboots and an apron made from a fraying sack.

One morning, Paul was shrieking repeatedly that he needed to do a poo. The teacher didn’t believe him, refused to let him go to the toilet and exiled him to the cloakroom instead. Plastic was all the latest rage. Sue was very proud of her new plastic lunchbox, and come the midday bell raced into the cloakroom to find her lunch on the floor and a steaming turd in its place. It could have been worse. It could have been my lunchbox and with my eyesight I may not have noticed the switch until it was too late.

So when one day Sue announced shyly that she had a joke to tell it was an encouraging sign that she was finally coming out of her shell. I parked my frustration to one side and listened to her tell a story about a woman who had a dog called ‘Tits Wobble’. One day, said Sue, Tits Wobble went missing, so this woman went to the police station. The teacher looked alarmed at this point and shot Sue a warning look, but she would not be denied. Not this time. In a surprisingly clear, strong voice, she described how the woman went up to the counter in the police station and asked the policeman if he had seen her Tits Wobble. ‘No,’ said the policeman. ‘But I’d like to.’

That afternoon the school bus had barely slowed to a halt outside our driveway when I was off, streaking indoors to snitch on Sue. She got her own back some months later when Mum was waiting on the roadside in an agitated state to tell us that our father had been seriously hurt in an accident and rushed to hospital. I started blubbing, asking between racking sobs if he was going to die. Mum immediately downgraded the serious accident to a flesh wound. That night at the imitation Formica, Sue turned to our father and said, ‘Guess what, Dad? When Mum told us you were hurt in an accident, Tommy was the only one who cried.’ I felt tears welling up again, but she wasn’t done. ‘And you don’t even like him!’ I started blubbing again. My father looked stricken with guilt before regaining his composure.

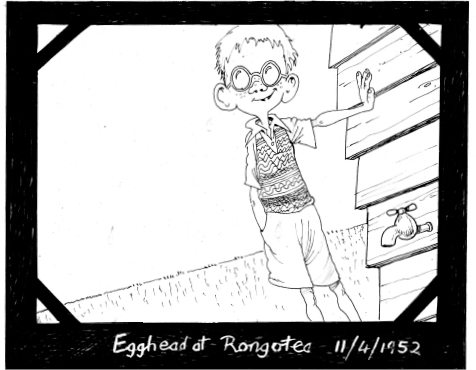

‘Would someone fetch the weeping bowl for Egghead, please? The Royal Weeping Bowl with the diamonds and the rubies in the rim! Tis a grand weep he’s having and he deserves only the finest weeping bowl!’

I was banished to my undersea world where, even as I was feeling sorry for myself, I marvelled at the richness of his language. Weeping bowl was brilliant!

THERE WERE MANY NIGHTS LIKE this. After my expulsion there would be a tapping on glass. Mum would have run around the house paddock in the dark, dodging rams and the U-boat to hand my unfinished meals in through a window.

When Woolworths announced a ‘draw your dad’ competition for Father’s Day—first prize was goods to the value of ten shillings from its Feilding store—I just had to draw the man responsible for ‘weeping bowl’. Sitting a discreet distance away, at an angle where he couldn’t see me, I sketched him in pencil while he listened to the radio.

On the day the winners were announced, I cycled to Woollies after school and checked out the two dozen or so badly drawn entries displayed in their front window. Mine was clearly the best by several light years, but to my stinging disappointment a blob barely recognisable as a higher primate, let alone a human face, had won first prize. I wasn’t even highly commended.

Feeling hard done by, I cycled home and complained bitterly to my mother. I felt a fresh stab of horror when Mum said she wasn’t putting up with this, leaped on her bike and started pedalling furiously into town. I could barely keep up.

‘It doesn’t matter Mum, really …’ I yelled as she crouched low over the handlebars like Lance Armstrong leading the peloton through the French Alps. When we arrived she flung her bike to the ground, pedals still spinning, and stomped indoors. I could hear shouting, then Mum emerged, hurling curses back into the interior. In disgust she reported that the manager’s excuse was that no child my age could possibly have drawn that picture, and they didn’t reward cheats.

I learned then that there is such a thing as being too good, or at least making it too obvious. Richard Prebble put it best when he said of a former Labour cabinet colleague, ‘Michael Cullen is too clever by three quarters!’ I learned this lesson again when my father taught me chess. I don’t know why, but I boasted to friends at school that the pieces of our set were carved out of solid white ivory and very rare black ivory. They demanded proof, and I had to lie again, saying that the set was too precious to take out of the house. In fact, they were cheap plastic, and hollow, which was just as well. With increasing frequency, heart in mouth, I started whispering, ‘Checkmate, Dad …’ and he invariably swept the pieces off the table in a fury.

This meant I wasn’t particularly looking forward to driving with him to Wellington for my long-promised eye operation. We didn’t have a car then; our mode of transport was my father’s khaki, ex-army, 4x4 Chev with weed-spraying booms folded over the front. It resembled a metallic insect at prayer.

The whole family came out to the gate to say goodbye. Mum tearfully handed me a ten-shilling note that she couldn’t afford. Twenty seconds later, as we were reversing onto Kimbolton Road, I managed to lose it. I blurted this out to my father. He cuffed me angrily about the head and I began crying softly and didn’t stop for ages. Not a word was exchanged between us the whole trip. The engine was so loud, conversation would have been difficult anyway, even without me whimpering and sniffling.

The Porirua motorway was under construction. Four-wheel-drive engaged, we slithered and slewed through slushy orange clay for what seemed like hours. When we finally arrived at Wellington Hospital my father handed me over monosyllabically to the staff. Clutching my pressed-cardboard school suitcase containing my pyjamas, a toothbrush and a packet of butterscotch hard-boiled sweets, I watched him depart, both of us dry-eyed. Doctors and nurses commended my courage and made a huge fuss of me, but in truth I felt only relief and something close to elation at seeing him go. I was soon busy endearing myself to older patients, soaking up their attention and approval like blotting paper.

Before the ether general anaesthetic I was given a spoonful of strawberry jam that aroused suspicion. It hid a bitter pill, a sedative. I don’t know why, but even today I can be eating a croissant and jam and the same bitter taste will flood my mouth. By the same token, in moments of joy and elation my mouth fills with the taste of butterscotch. I have no explanation for this.

After the operation my eyes were swathed in bandages, rendering me sightless for two weeks, one of which was spent at Calvary Hospital in Wellington. There is no painless way to remove sticking plaster from eyebrows, and I dreaded having my bandages changed by nurses and nuns, who realised it had to be done in one swift yank. I had no visitors. Feilding was too far away. Parents of local children adopted me and I amused them with Sidney stories as well. I was in full pluck mode. I didn’t need to actually see people laughing. All I needed was to hear it.

I STILL NEEDED GLASSES, BUT afterwards my eyesight was good enough to play rugby without them. Half-blind, I tended to run unwittingly into other boys, which delighted teachers and parents on the sideline because they saw it as naked aggression. Working on the topdressing truck in the weekends meant I was stronger than other boys my age, and whenever a rugby ball swum into focus I could pretty much wrench it off anyone or out of any maul. I had no other skills but these two attributes alone marked me as a player of potential.

Mr Sullivan, my teacher in Standard 5, a thoroughly decent, roly-poly man, who sometimes drove the school bus and always smelled as if he hadn’t washed his hands thoroughly after going to the toilet, was determined to get me in the top team, but I would have to go on a strict diet to meet the weight requirements. Two weeks of agonising denial followed. I woke on the morning of the big weigh-in so hungry I could have eaten my own underpants, only to discover they were in the wash. I only had the one pair. It meant secretly borrowing a pair of my father’s voluminous Y-fronts. Their buttery appearance unnerved me, but Mum assured me they were not Sidney’s.

I pulled them on with a heavy heart. There seemed to be yards and yards of surplus cloth, which I tied up in a big knot at the front. They bunched between my legs and almost reached my knees. I looked like Gandhi in his dhoti if you can imagine Gandhi with legs like a Russian shot-putter. It was a struggle pulling my shorts over the top.

At school, Mr Sullivan marched us to the grocery store down the road. In the shed out the back there were Avery platform scales with a side-arm and sliding weights. On these scales sacks of sugar, flour and salt were measured out into smaller brown paper bags. We lined up in bare feet to stand on the tray. I hung back while other boys passed easily.

Finally, it was my turn. As I feared, bone density came into play again. The instant I stepped on the platform, the side-arm jerked skywards. ‘Take off your shirt!’ boomed Sullivan. It made no difference. ‘Take off your singlet!’ It still made no difference. ‘Off with your shorts, lad!’ I was most reluctant. ‘Come on, boy, I haven’t got all day!’ Utterly heartsick, I began tugging and wrestling down my tight shorts.

I’ll always be grateful to Mr Sullivan for what happened next. When previously compressed fabric, relishing its freedom, began billowing from my crotch much like those CGI reenactments of the Big Bang you see on astronomy documentaries, he started screaming, ‘Pull them up! Pull them up!’

It meant that as an eleven-year-old I played rugby against teenagers from local high schools. My voice wouldn’t drop for another three years and then only to the tones of a strangled tenor, yet here I was sharing changing sheds with guys with chests carpeted in Velcro and genitals that thwacked against their thighs. One huge boy used to push into the hottest part of the showers, bellowing, ‘I can stand the shit if you can stand the pain.’ People tended to get out of his way. Coming back on the bus from rep team trials held on vast Ongley Park, not that much smaller than the Serengeti, in Palmerston North, rather than calling for a toilet stop to get rid of the illicit beer he had guzzled, he insisted that we lift him flush against a narrow skylight in the roof so he could pee with the jet-stream. Unfortunately, gravity proved the stronger force and urine sprayed back into the coach.