AT HIGH SCHOOL, SUE WAS shunted into home craft and I was drafted into the top academic stream, 3P1, where I hardly knew a soul. To my class-conscious eyes they seemed to me to be the spawn of Feilding’s aristocracy, if a small country town can have such a thing. Confident, carefree children of doctors, dentists, lawyers, accountants, bank managers, haberdashers, header-harvester salesmen, seed and grain merchants, freezing-works bosses, plus a few heirs to vast pastoral estates. For the first time I felt out of place in the one place I had always felt right at home—school. It didn’t help that I was assigned another boy with thick glasses as my desk mate—Wesley Bell, the short, chubby son of a Methodist minister. We were both nerdy and my guess is the teachers felt we’d be good company for each other, and this seating arrangement wouldn’t punish two other kids unnecessarily.

Wes asked me in a whisper if I had been invited to Russell McLean’s party. Russell was a tall, plump boy with no discernible knees. His legs were like wedges of camembert cheese. The thick ends of the wedge emerged from his long shorts and the sharp ends vanished into his socks—which were always pulled up. He was the son of ‘Fatty’ McLean, the headmaster. They lived in the two-storey residence attached to the boarding school in the school grounds.

I hadn’t been invited to Russell’s party. Nor had Wes. Everyone else in 3P1 had. This pattern was repeated right through to the seventh form, with Wes and I sharing the Cinderella role. Russell’s dad didn’t like me much either. Reading out the list of pupils accredited University Entrance, Fatty glowered when he got to me and said that the following name gave him no pleasure at all. What had I ever done to him?

Oh yes, at the end of every term every form gave an end-of-term report in front of the whole school. In spite of feeling like the class leper, I must have amused my classmates because they nominated me for the task at the end of the first term in that first year, and they kept nominating me every term for the rest of my time at Feilding Ag. Other class spokespeople talked earnestly about trips to nature reserves, teachers who had just gotten engaged, or someone in their form excelling in some external music exam or gymnastic event—all very dull to most pupils, who would never excel in anything except stealing cars and teenage pregnancy. I shamelessly ransacked Reader’s Digest for jokes, made up some of my own, and did three minutes of stand-up where I mocked teachers and classmates who shone. The assembly loved it. The staff and Fatty hated it.

I was in full flight one assembly condemning the ‘cheek and audacity’ of a teacher when Fatty spotted his chance to deliver some comeuppance. Rising to his feet—always a struggle—and adjusting his black gown like an obese raven flapping its wings, he loftily asked me to explain the difference between cheek and audacity. ‘Spelling, mainly!’ I responded cheerfully, to loud laughter and foot stomping from the school.

Fatty got his own back at prizegiving in my final year—making sure I wasn’t given any. There were about fourteen of us in the seventh form. Classmate after classmate got prize after prize, award after award. Some were vanishing from view behind stalagmites of books such as Winston Churchill’s A History of the English-Speaking Peoples and the collected works of Charles Dickens. I got nothing, a fact not lost on the rest of the school. Everyone in the seventh form, however, got Higher Leaving Certificate no matter what, so when my name was finally called and I walked cockily to the stage, the packed stadium went crazy. The applause from pupils seemed to roll on and on while Fatty went puce and called for order. I was wondering if I had imagined this, until a few days later a local clergyman clutched me in the street to express his astonishment and congratulate me. He didn’t say it was the second coming exactly but that was the inference I took.

I have been the guest speaker at two Feilding Ag prizegiving evenings since then. I disgraced myself on the second occasion and I doubt that I’ll be invited back. Pointing to the gleaming kauri honours boards hung around the walls bearing students’ names written in gold, I told the assembly that they wouldn’t see my name on any of them and they wouldn’t recognise any of the other names, ‘because these kids peaked in high school!’ I added quickly that ideally you should peak on your deathbed, but it was too late for the appalled staff on stage with me. Heresy had been committed. I could hear ice crystals tinkling in the air. Somewhere Fatty McLean is still spinning in his grave. Well, revolving slowly at least.

I CUT AN ABJECT, LONELY figure in my early weeks at high school. It was a stinking-hot summer. There was a teaching hiatus during which staff battled to set the timetable. Boys had military drill, disassembling Bren guns and drinking warm lemon cordial from metal milk urns, while in an adjacent sports field the girls tucked their skirts into their knickers and danced with hoops. We had separate swimming sessions in the school baths. This puzzled me until I stepped inside the eight-foot-high wall surrounding the swimming pool and saw hairy masters and boys frolicking together, buck naked. In shock I huddled as inconspicuously as I could high in the stands alongside a doughy boy, who introduced himself as Anderton the younger. His older brother was a prefect in the boarding house and his duties included wank patrols of the dormitories after lights out. I was thirteen, but had absolutely no idea what he was talking about.

‘What’s a wank?’ Anderton shifted uncomfortably when he could see I wasn’t having him on. He lowered his voice.

‘You play with your cock until stuff comes out.’ I reeled back in disgust.

‘What’s the fun in that?’

Deciding not to be too hasty, I gave it a try that night. I thought for a few terrifying moments that I was bleeding and that I might be anaemic, but the panic was fleeting. I quickly realised that if I dedicated myself to the task and was prepared to put in the hours like an aspiring concert pianist or tennis professional, this was something at which I could excel. And so it proved to be, if only to a rapt, appreciative gallery of one.

At primary school, during what I call my Peter Snell period, it baffled me when high-school boys on the bus twisted my arms up my back, demanding I draw pictures of naked women with legs akimbo for them. They insisted on anatomical precision. Luckily their knowledge in these matters was as imprecise as mine, and they went weak at the knees at anything circular. After my bringing-up-to-speed from Anderton Minor their appetite for such imagery made more sense.

Apart from the Daily Mirror comic strip ‘Jane’, about a gorgeous, leggy ingénue constantly falling out of her clothing, only available in intermittent airmail omnibus editions, there was no virtually no pornography of any kind readily available. One day I noticed that full-page ads for women’s lingerie in the Manawatu Evening Standard were printed so badly that bra and knicker tones were barely distinguishable from the surrounding flesh. With a few deft strokes of my trusty 2B pencil I was able to fashion nipples and alluring triangles of pubic hair. These were immediately put to good use, and when I had sufficiently recovered I destroyed the evidence lest it fall into the wrong hands. Homemade erotica can only take you so far.

One afternoon in the abandoned cowshed I found an old milking cup with rubber lips that I thought, suitably lubricated, might approximate the real thing. Years later I was able to confirm what I suspected at the time—it didn’t. Not even close. I’ll spare you the details, but I climbed out of the iron vat I’d been hiding in and traipsed home wretched with guilt, self-loathing and despair.

A week later I noticed for the very first time tiny, slightly raised lumps, not quite pimples, on either side of the dorsal vein of my penis where it emerged from the pot-scrub of ginger hair. Sebaceous glands are common in adolescent males and become more visible when skin is stretched for whatever reason. A ten-year-old boy with access to internet porn knows this now. I did not know this back then. All I knew was that a suitable incubation period had passed since the hugely disappointing milking-cup experiment and I trembled with terror. It was blindingly obvious. I had caught venereal disease. Worse, I was still a virgin. It was doubly wounding and humiliating. How could I explain this to our family doctor?

Dear old Doc Mowbray made house calls when we were kids. He gave me one of his fountain pens that smelled deliciously of his pipe tobacco. He had diagnosed my inflamed appendix and had me rushed to hospital just as it was about to burst. I was still alive in significant measure due to him. How could I sit opposite him while he carefully put away his magnifying glass before turning back to me, eyes brimming with tears, to report that I had the pox? And not just any old pox, in this instance cow pox. It implied bestiality—a criminal act as well as a sin. It was a deeply scalding, shameful secret that I would have to take to my grave.

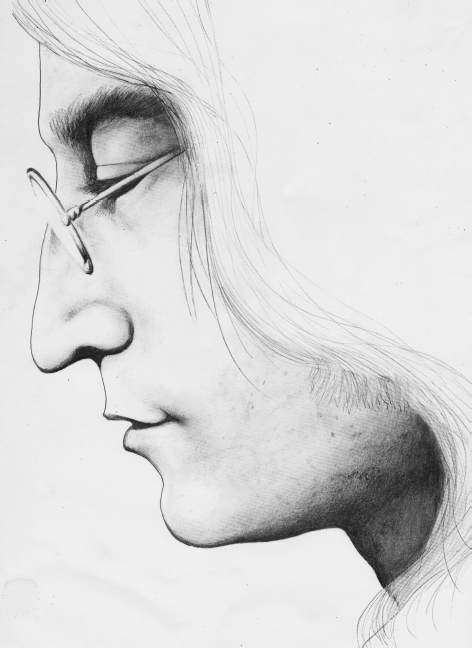

It meant girlfriends were out of the question. There were other factors that made this prohibition easier for me than it would have been for other boys (apart from Wes, obviously). I had mousy curls bordering on ginger. I wore heavy glasses that refused to sit straight on my head. I was badly knock-kneed, with a scythe-like sweep of my right leg—even today I can be crossing a street and see a ridiculous reflection in a shop window, start to giggle, then realise with horror that it is my own.

BUT I WASN’T GOING TO let venereal disease completely destroy my life. I went to the first high-school dance because I still had long pants that fitted (only just—they stopped just below my shins). Dad drove us there in his newly purchased secondhand Vauxhall Velox, with his old Air Force chum, Jock Laidlaw, in the front passenger seat, both of them giggling drunk. Sue and I sat nervously in the back.

Fatty’s imposing house was attached to the boarding school and had a circular drive that Dad thought we should drive around, tooting the horn. In the middle of the circuit he decided to park at the front door, still tooting furiously. Jock was in hysterics. Sue and I were horrified. Fatty’s unmistakable silhouette approached down a corridor towards the glass door then, like an eclipse of the sun, blocked all the light apart from a thin corona. The door opened. Fatty stepped out. My father fumbled with the keys. Fatty waddled towards us. The car stalled. Fatty gathered speed—no mean feat in itself. The Velox kicked into life and we lurched off with Fatty shaking his fist at our departing tail-lights. Jock was paralytic with laughter and Dad was slumped over the steering wheel, gasping for breath. They had had such a good time they decided to do it again, tooting the horn continuously but not stopping this time. Sue and I asked to be let out down the road so we could not be linked to this incident, and slunk into the school hall.

I was having a great time until I couldn’t find my dance partner. The hall was partitioned with planters filled with shrubbery. Soaked to the skin in sweat, I was rehydrating with soft drink when I heard her voice coming from the other side of the greenery. ‘Don’t dance with Tommy Scott. He’s a terrible dancer!’ It was a knife to the heart. I sat out high-school dances after this, and have avoided dancing to this day.

Sue had a great night though, and was keen to go the following year. Mum helped her make a new frock specially, which took weeks. Sue kept asking our father, ‘You will take me, won’t you, Dad? You won’t forget?’ He got irritated.

‘How many times do I have to say yes, for shit’s sake?’

On the night, Sue was ready with her hair beautifully done by six. At seven there was no sign of our father. At eight we feared the worst. At nine Sue took off her frock, folded it away neatly, went to bed and cried herself to sleep. The next day I told our father he owed Sue an apology and he hurled a plate of food against the wall—which brought this particular topic of discussion to a close.

IN THE FOURTH AND FIFTH forms, my school clothes were pretty much the only clothes I owned. On mufti day, when you could wear what you liked, the only kids turning up in school uniform were Māori kids and me. To break this trend in the fifth form, on mufti day, after my father had left for work, I borrowed his tweed jacket, corduroy pants and brown brogues. It was before my growth spurt, so nothing fitted properly. Everything was outsized and baggy like a clown’s outfit.

No one said a thing all day. I thought I had pulled it off until the very last period, when Christine Wilson suddenly blurted out, ‘Tommy’s wearing his father’s clothes!’ Every head swivelled. She was a lovely girl incapable of cruelty. It must have been shock that triggered her announcement. She later wrote the screenplay of one of the great Australian films, Rabbit-Proof Fence, under her married name, Christine Olsen.

I didn’t socialise with anyone in my class. Not making the cut to Russell’s parties still stung, so I made sure I rejected the other kids before they had a chance to reject me. After school I cycled straight home, dawdling for hours if necessary if other kids on bikes were with me because I didn’t want anyone seeing where we lived.

My father had spent much of the previous winter soldering up and assembling a kitset transistor radio the size of a sewing machine, which had pride of place in the master bedroom, home now to brand-new twin beds with blonde-oak headrests with shelving, the candlewick bedspreads always immaculately made up. The local radio station started playing pop-chart songs late in the afternoons. At the appointed hour I crept in. To leave no trace of my intrusion, I lay on the floor between the beds and switched on the transistor. It was from this prone position that I heard something that made me sit bolt upright with a feeling approaching pure joy coursing through my body.

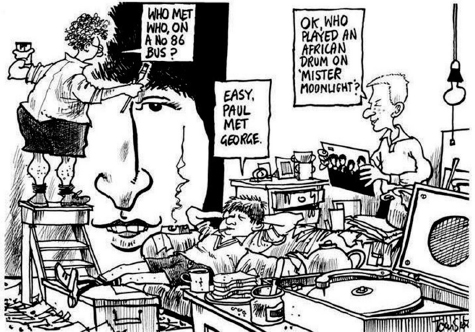

It was instantly familiar yet stunningly different. It had a shuffle beat, raw, urgent harmonica and glorious harmonies infused with yearning. It was Love Me Do by a group I’d never heard of—The Beatles.

Their sudden global ascension was the one shaft of sunlight in a year made dark by the assassination of President Kennedy, which was also Fatty’s finest hour. He told sobbing girls in assembly that a terrible thing had happened but America would survive this tragedy and the world wasn’t coming to an end. It made up for the time he told assembly that there had been too much thieving from lockers, that he knew who was responsible, he was going to stamp it out—and could all the Māori pupils stay behind please.

In the wake of the assassination I fantasised that I was a brilliant brain surgeon, able to piece Kennedy’s cerebral cortex back together and make the whole world happy again. It was my own cerebral cortex that needed fixing. I was swimming laps in a pool of my own sorrow. Photos exist of me smiling happily with baby brother Rob on my knee, then a few years later, baby Sal, yet such was my self-absorption in the Makino Road years I barely remember my siblings at all.

Michael was cheerful and robust. He fell in love with The Beatles as well and somehow acquired an acoustic guitar and devoted most of his time to learning that. Together we built a two-storey tree hut in a spreading macrocarpa and beautiful little Jane was allowed to play with us in that. She came with us on raiding parties over the hill to Feilding’s lawn cemetery to loot marble angels that we brought home in triumph—which had Mum frantically crossing herself and wailing that we would all burn in hell.

Robbie was approaching school age and I read him stories before he went to sleep. I thought he was a gifted child because he would take the book off me and read it back word for word. In fact, he was profoundly dyslexic and just had a prodigious memory.

My memory is not prodigious at all when it comes to my sister Sally Anne at that time. She is a kind, funny, pretty, supremely well-adjusted woman today so I’m picking she can’t remember her Makino Road days either.

Sue, who was always far lovelier than she ever allowed herself to feel, attracted the attention of a slick young man who owned a Jag, which both thrilled and alarmed Mum. Sue wouldn’t let him anywhere near the house. He had to park on the road, toot his horn and wait there while she tottered up the gravel drive in her high heels to meet him. It was the same after the movies or a dance. Regardless of the hour or the weather, he had to drop her off at the top of the drive. One night Mum, who was a Neighbourhood Watch group of one, decided they had been parked up far too long, so the spoilsport, the virgin with VD, was dispatched into the dead of night to tap on the fogged-up windows.

Sue left high school within a nanosecond of turning fifteen to work as a nurse aide in Feilding Maternity Hospital and board in the nurses’ home. I always thought it was because she couldn’t wait to escape but only recently she told me that Mum encouraged her to quit school and earn money.

She had barely settled in when she got a distraught phone call from Mum. Out of the blue, relatives from Ireland had contacted her to say they were on their way to see us. They had just landed in Auckland and were staying with friends for a few days before hiring a rental car and driving down in the weekend. In tears, Mum begged Sue to head them off. Barely fifteen, she cycled to Feilding railway station, caught the Limited at ten o’clock, spent a nervous, chilly night wide awake in a click-clacking carriage, arrived in Auckland before dawn, caught a bus to the suburb of Westmere, walked for miles alongside tidal flats to a stranger’s address, knocked on the door and told cousins she didn’t know that her mother and father had gone away, she wasn’t sure where or when they would be returning, so they couldn’t come to Feilding. And they didn’t.

SUE CAME HOME SOME WEEKENDS lugging one of her very first purchases—a portable, battery-operated gramophone and two long-playing records: Johnny Tillotson of ‘Talk Back Trembling Lips’ fame, and The Beatles’ first album. I listened to one song on side two over and over until the batteries went flat: ‘There’s A Place’. Attributed to Lennon and McCartney, it was written by John. No matter what was happening or how bad he felt there was always somewhere he could go, it was his mind, and no time was he alone …

That song spoke to me more than any other song had ever done before. My classmates went around humming ‘Four Strong Winds’ and ‘Tom Dooley’, which was another good reason for hanging out with coarser types in the woodwork and metalcraft streams who were into The Animals, The Kinks, The Rolling Stones and Manfred Mann. Walking across the quad some lunchtimes there could be up to ten scruffy boys, socks around the ankles, singing ‘Doo Wah Diddy Diddy’ in joyous, ragged unison.

Metalcraft came in really handy. The Beatles had Vox speakers so these guys spent a lot of time in class working furtively and feverishly with hacksaws and sheets of metal to fashion impressively realistic Vox insignias to screw on the front of their crappy old amps and rubbish speakers.

The late, great American comedian Rodney Dangerfield once described going into a gay bar as follows: ‘It was amazing! There were two guys for every guy.’ Almost overnight in Feilding there were two bands for every band member. A sweet, shy, retiring, bespectacled boy called Len Sithebottom, arriving from Liverpool with a trunk full of War Picture Library comics, was dragooned into playing drums in a band while still jet-lagged, purely on the basis of his Scouse accent. Only dead people and I had poorer timing than Len. I was tone deaf as well. I make Leonard Cohen sound like Pavarotti. With the wisdom of vet-school-acquired hindsight I now blame the bone density of the hammer, anvil and stirrup in my middle ears. This limited my contribution to the rock-music revolution sweeping the world to carrying amps and painting the names of bands on the drum kits. This kept me busy, as they were always changing. My favourites were Rommel’s Lake and Atomic Porridge.

The Atomic Porridge story is a darkly comic, absurdist saga worthy of another book at another time, but it would be remiss of me not to pay homage to Ray Fiddler, one of the lead singers. Ray sounded like a cross between Paul McCartney and John Lennon. He had such stage presence that when the drummer vanished from the stage, which he did frequently to deflower schoolgirls behind the back curtains, Ray, armed only with a tambourine or maracas, kept the band driving forward, winking knowingly at me, the wistful, envious virgin with VD, taking money at the door.

Ray’s parents were hip and sophisticated. They had Esquire and Life magazines placed casually on a coffee table. They had a drinks cabinet. After school, if his mother was out, Ray poured his mates hefty tumblers of Bacardi and Coke. There were occasions when some of them reeled outside and chundered on the Fiddlers’ immaculate back lawn. They had a radiogram with jazz albums stacked neatly against the wall. I first heard Dave Brubeck’s cool classic ‘Take Five’ in their living room. I was able to listen over and over again to Bridge on the River Wye starring my comic heroes Spike Milligan and Peter Sellers—doing a genius impersonation of Alec Guinness. Mrs Fiddler kindly insisted I stay for meals and I cycled back to Makino Road in the dark, no light, no helmet, guided by starlight on fence wire, shouting out in character my favourite Milligan lines, startling sleeping cattle who stampeded in the dark, crashing with a spronging sound into distant wire fencing, with me laughing my head off. I did a near perfect Major Dennis Bloodnok, Ind. Arm. Rtd., coward and bar.

The laughter stopped at home. The clothing situation was getting grim. I began roaming surrounding farms in search of dead sheep to pluck. If they weren’t ripe, I dragged them into thickets of gorse or stands of bush, coming back a few days later when they had bloated, their bellies blue and stinking to high heaven. I had to battle nausea, but the wool came off much easier. I sold numerous sackfuls to a wool merchant in Feilding and bought my first pair of black jeans, a sports coat and a shirt with a button-down collar like Michael Caine’s in Alfie.

School Certificate was looming. I took it very seriously. On the morning of the English exam, Mum fed me fish because it was good for the brain. I hated her fish because she favoured the rolling-boil method—you throw the fish into a bubbling pot, jam on the lid, come back in an hour’s time and strain the flakes. Rather than cycle to high school, I chose this morning to take the bus to do some extra swat. The bus was late and I was very nearly locked out. Damp with anxiety, I sat down and began answering the comprehension question. To my horror, I couldn’t remember how to spell the three-letter word used to join two parts of a sentence together. I scribbled the three options in the margin of my exam paper, now sodden with perspiration and cobwebbed with spreading ink:

nad

dan

and

They all looked correct. I picked one at random and soldiered on, close to tears.

LATE IN JANUARY THE FOLLOWING year word went out that the exam results were due any moment. I was still in bed when my father collected the mail from the letterbox at the gate. There was a terrible, theatrical wail from the kitchen.

‘Oh no! Oh dear! Woe is us! Someone fetch the sackcloth and ashes!’ shouted my father, loud enough for the whole house to hear. ‘EGGHEAD HAS FAILED!’

I went numb and couldn’t move for an hour. Mum eventually crept into my bedroom with a cup of tea and a piece of toast. What was I going to do? Would I repeat the fifth-form year? My life expectations had already shrunk to sub-atomic proportions at this point. We couldn’t afford that. I would accept my fate and settle for a life on the chain or in lamb-cuts in Borthwicks’ Feilding freezing works. I knew lots of good people who worked there. Some of them owned their own homes and speedboats before they were 30. It would be OK. ‘Don’t worry, Mum, I’ll be fine …’ I sniffed.

It was after one in the afternoon when I eventually shuffled like a zombie into the kitchen and reached for the opened envelope resting on the mantel above the coal range. I had passed, thanks to good marks in Biology, Chemistry and Mathematics. I got only 47 in School Certificate English—which meant I could never be a journalist, screenwriter or author. Those are the breaks.

IT WAS A HUGE RELIEF being a sixth-former. The ranks had thinned and there were only enough pupils left for two professional classes. Mum was very proud of me and decided to attend a parent-teacher evening in a fierce thunderstorm. I put the other kids to bed, listened to some National Radio, probably Manuel and his Music of the Mountains, for a couple of hours, looking out our curtain-less windows for some sign of her pushbike light bobbing in the downpour. She got home close to ten, completely saturated, reporting indignantly that my English teacher thought that I was a complete idiot who would never amount to anything. I sighed and handed her a cup of tea.

‘Don’t you worry, Junior! I got back at the bastard quick as a flash!’ She beamed proudly—which worried me. ‘I said to him straight, don’t think yer shit doesn’t stink, Sonny Jim!’

Later that year we moved out of Makino Road to a nice house in the borough of Feilding itself. We had the freezing works over the river, the wool scourer across the railway lines and the largest saleyards in New Zealand down the road—an olfactory Bermuda Triangle where fresh air vanished without trace.

I got a job in the school holidays working as a labourer on the cooling floor in Borthwicks. Mum saw an ad in the Feilding Herald—Farrell’s shirt factory wanted trained machinists or women willing to learn. To the collective horror of her children, she applied. This was well before the feminist revolution. We were in no position to be snobs but we implored her to reconsider and spare us the shame and humiliation of having a mother who worked. I don’t know where this objection came from. Doing the washing in a wood-fired copper and wringing the sheets through a hand-cranked mangle meant she was already a manual labourer. Our shame and humiliation vanished magically with the arrival of the television set that she managed to scrape together a down-payment for.

In the high-school library there was always a queue of boys waiting to look up the meaning of ‘vagina’ in a heavy, leather-bound dictionary. It sprang open automatically to this greasy, well-thumbed page in the gentlest of breezes. While waiting my turn, I rifled through the shelves and came across Three Men in a Boat by Jerome K. Jerome, which made me laugh out loud from the very first paragraph. It was a revelation discovering just how amusing the printed word could be. In the 1950s and ’60s, publicly at least, New Zealand was probably the most humourless country on the planet. I’d put money on Holland being funnier. We gave the impression of being gloomier than Vladivostok in winter.

Frank S. Anthony’s Me and Gus stories, written in the 1920s about likeable losers trying to establish dairy farms in harsh inhospitable swamp-land at the base of Mount Taranaki after coming back from the Great War, have a bleak charm and were once very popular but have long since fallen from view. In the 1950s there was a limp, patronising and racist column in Truth called ‘Half-Gallon Jar’, written by a Pākehā taxi driver who used the pen-name ‘Hori’. On radio there was the Howard Morrison Quartet singing ‘My Old Man’s an All Black’—a lame play on Lonnie Donegan’s already lame ‘My Old Man’s a Dustman’. A song called ‘Taumarunui on the Main Trunk Line’ by Peter Cape was demanded by a comedy-starved populace at every single request session and never failed to depress me. This doesn’t mean that Kiwis weren’t funny. When you read World War Two biographies there is a plenty of evidence of a wry, ironic and understated New Zealand sensibility—we made each other laugh out loud. There just wasn’t much public expression of it.

This was before Barry Crump’s comic novel A Good Keen Man hit the country like a thunderclap in 1960. Along with everyone else, I delighted in the novelty of the rollicking slapstick, the vivid, visceral accounts of life in rugged bush country and the sound of the Kiwi vernacular coming off the page, but there was a darkness and nihilism in there as well—especially in his unsympathetic depiction of women. Men didn’t divorce wives or go to marriage guidance to mend relationships—they simply ‘shot through’. Years later it emerged that, when intoxicated, Crump could be an abusive and angry husband and father to his wives and children. He may well also have been sexually conflicted. The outrageously camp Auckland actor Peter Varley loved recounting how he was once locked in intimate union with the famous author and star of the brilliant Toyota Hilux television commercials and, being exceptionally well endowed, leaned over the great man’s broad shoulders and enquired solicitously, ‘I’m not hurting you, am I, Barry?’ The reply came from damp lips dangling a roll-your-own, ‘Nah, she’s beaut, mate.’

Later, Puckoon by Spike Milligan and Catch-22 by Joseph Heller would also reduce me to helpless laughter. I daydreamed fancifully about doing something vaguely similar one day. On a long bike ride with my brother Michael, sniffing out dead sheep to pluck and checking out orchards to raid, I found something in a long-abandoned Makino schoolhouse that would push me in that direction. The building was in ruins. All the windows were smashed, desks were upended, parts of the ceiling had caved in and the floor was strewn with sheep droppings. In a corner, hidden under a pile of sacking, was a soggy copy of a controversial magazine that had been banned by the Feilding mayor. On the full-colour cover was a well-drawn cartoon of a man dying of thirst in a burning desert with a mirage of a beer tanker shimmering just out of his reach. It was a Massey Agricultural College capping publication—Masskerade 59.

Ten years later I would edit Masskerade 69 and be threatened with prosecution for blasphemous libel. This edition did not mock religion directly but there were more than enough risqué jokes and filthy cartoons to give any man of the cloth conniptions. To borrow from another comedy hero of mine, Frank Muir, my flabbers were absolutely gasted. I knew intuitively I had struck gold. I tucked it inside my singlet and hid it when I got home.

Feilding Ag was quite enlightened for its time. Pupils had their own self-government. Every class had a representative on the school council, which met regularly in beautiful council chambers and did radical things like abolish caps. Having power of veto, the staff would immediately make them compulsory again. Half the school prefects were appointed by the staff, the other half were elected by school houses. My whānau, Rangitikei House, elected me.

The boy prefects and the girl prefects enjoyed separate common rooms in the lovely old school building, sadly long gone. Without ever revealing my mother lode, I told an endless stream of filthy jokes, which offended a huge boy called Warren who was deeply religious. Unable to stomach my obscenity any longer, he dragged me out the door and threw me down a flight of stone steps. Weak with laughter from a freshly delivered and, if I say so myself, perfectly timed punchline I was unable to offer any resistance. It didn’t matter. I was so full of dopamine—a byproduct of sex, which didn’t apply in this instance, and laughter, which did—that I felt no pain. In seconds I had bounded back through the door to tell a joke about a gorilla sodomising some nuns. Warren gave up.

In the seventh form, out of the blue, some classmates asked me if I wanted to come with them to see a capping revue in Palmerston North’s wonderful old Opera House, again sadly gone, making way for a shopping complex. (I am totally opposed to the death penalty—I think it is barbaric—except for property developers, town planners and architects.) The show was amazing and wonderfully funny. A tall, thin, ginger man, an Antipodean John Cleese called Tony Rimmer, stole the show. At one point he came dashing out in front of the curtain, wringing his hands in panic, to ask if there was a doctor in the house. A plant rose and said he was. ‘Enjoying the show?’ asked Rimmer. ‘Very much so’ was the reply, and the auditorium erupted in relieved laughter.

In the car on the way back to Feilding we were still bubbling with excitement. One of the girls—it might have been Christine Wilson—said quietly, ‘You will write one of those shows one day, Tommy.’ The others swiftly agreed. I sat in the back dazed and amazed at this vote of confidence.

They dropped me off where I had left my push-bike at the entrance to the school grounds and I cycled home mulling this over. Could something that wonderful ever happen to me? To Egghead?