AFTER MY IGNOMINIOUS DEPARTURE FROM vet school I had a year to kill before Massey set up physiology as a stage three unit, which I needed to complete a rather tatty Bachelor of Science degree. I did a philosophy paper and a biochemistry paper, but mostly I drew cartoons for the student newspaper Chaff, and was a judge of Miss Massey, held on the cricket oval in front of the refectory.

I can picture it now. It was a warm, still evening. The grass was the colour of emerald. The setting sun lent the terracotta art deco buildings a pink glow. Young girls, hair and makeup perfect, jewellery sparkling, wearing glamorous gowns, approached the oval in an excited giggling gaggle … falling silent when they saw the temporary drafting yard that some ag students had set up on the lawn. Guys in black bush-singlets, shorts and gumboots (and this was well before Fred Dagg), armed with whistles and rattles and assisted by yapping dogs, rounded them up into a holding pen, where they stood ashen-faced until another gate was thrown open and with a lot more shouting and barking they were unceremoniously herded down a narrow race, on either side of which guys in white coats armed with red and blue raddle marked them on the back as they tottered past in their high heels towards a drafting gate, to be culled into the clearly identified finalists’ pen or the ugly pen. Dazed girls fought back tears when they examined ruined ball gowns, not to mention the more permanent, incalculable damage to their self-esteem if they ended up in the ugly pen.

I hasten to add here that I was not part of this pre-selection process. I was dressed sombrely in a tuxedo, as were a city councillor and the local MP, the rotund and jolly Joe Walding. We merely mingled with the finalists, deliberated in private, then declared a winner.

I know what you are thinking and I quite agree. We have gone backwards as a society.

At the cocktail party afterwards, Joe, who was not afraid of a knife and fork, was piling hors d’oeuvres onto two plates as if a bell were about to ring sounding that time was up, caught my eye and looked guilty. I repeated an Ambrose Bierce quote that an abstainer was a weak person who yielded to the temptation of denying himself a pleasure. He got very excited and made me hold his plates while he scrambled for a pen and paper to write it down.

Some years later, at a parliamentary reception for a visiting rugby team, where Joe was keeping pace with giant locks at the canapés table, matching them mouthful for mouthful, I witnessed him whip this note out of his pocket and recite it gleefully. On the campaign trail of the 1984 snap election, the Labour Party appointed Joe as David Lange’s minder because he was very shrewd, had a calming presence and every time they sat down to dine together, Joe’s eating habits made David’s seem anorexic.

—

A REPORTER AND A PHOTOGRAPHER from the local paper usually covered Miss Massey. One of them told me the Manawatu Evening Standard was on the lookout for a cartoonist, and the editor, Denis Wederell, would like a word with me. Drenched in Old Spice and looking as much like a Young National as I could, I met Denis in his office. A very short, personable, bald man, he offered me a job on a trial basis for the princely sum of $5 a cartoon. That settled, we went downstairs to visit the paper’s owner, the ancient and venerable N.A. Nash, in his gloomy, mahogany-lined office. The paper had been in the Nash family forever—more than a business, it was a dynasty unparalleled since Rameses. Old N.A., who was 90 in the shade, reached for my sample folder with a trembling, liver-spotted hand. Grabbing a cartoon at random, he fixed it with a watery stare for all of two seconds before pushing it away.

‘One thing we’re all tired of is students! You can’t pick up a paper without students rioting somewhere—I want nothing about students, understand? And Vietnam. I’m sick of Vietnam. Just be funny.’ To his credit, Denis suggested I be allowed a certain freedom of expression. This incensed N. A. I thought the old bugger was going to die. He started wheezing and shouting that the paper was worth millions and they weren’t going to have me jeopardise it in any way. He asked me if I knew how much his paper was worth. I didn’t.

‘Lots,’ he said. ‘Do you know the Prime Minister’s wife, Mrs Holyoake?’ I didn’t, as it happened. ‘I do. Lovely woman!’

Following this illuminating chat, we returned upstairs, where Denis gamely opined that N.A. was a remarkable man. ‘He can sound so wrong so much of the time, yet it’s truly amazing how often he is right.’

I didn’t mind—I had my first paying gig, and was assigned a tiny office off the newsroom. Every cartoon was preceded by an editorial conference.

‘Has anyone got any ideas for Tom?’ No one ever had any ideas for Tom. Denis would look in my direction.

‘Any ideas, Tom?’

‘Well, Mr Wederell—Denis, sir,’ I would cough, ‘I was half wondering about these campus riots …’ My voice would trail off as Denis’s face lit up. ‘Rail fares to Auckland! Gone up again. Preposterous! Go to town on that!’

The next day every newspaper in the country was full of stories about the All Black trials for the upcoming series against the Springboks and the arrest outside the grounds of demonstrators opposed to New Zealand rugby teams touring South Africa. I suggested a cartoon about this big news story and was stunned when Denis agreed. Twenty-four hours after publication, a shamefaced Wederell told me N.A. didn’t get it (I think the old boy did) and my trial was terminated. I had lasted barely a week.

I wrote about this brief foray into newspaper cartooning for Chaff. In the article I said that Denis was the same height sitting as he was standing. He sued for libel. I wanted to go to trial and summons Denis to the witness box (I was an old hand at this now), and ask him to sit, then stand. ‘No further questions your Honour. The Defence rests.’ The Student Union settled out of court for $600 dollars. It could have been more, but the libel was contained. When the offending issue of Chaff was dropped off in bundles around the city, Manawatu Evening Standard reporters were dispatched like commandos in dawn raids to snatch as many copies as they could find before they fell into anyone else’s hands. Their orders were then to destroy them.

The late, legendary head of TV3 News, Gordon McBride, was a print man early in his career and came up from Southland as a young reporter to work on the Manawatu Evening Standard. On his first day, the deputy editor waved him across to his desk, discreetly slid open a bottom drawer and winked. Expecting a copy of Penthouse, Gordon peered in all excited and saw instead the offending issue of Chaff, open to my article.

Denis Wederell had long since left the building. We had both moved to Wellington. I would sometimes see Denis on Lambton Quay in the mid ’70s. When he saw me coming he would dash through traffic to get to the opposite pavement to avoid contact. I thought he was going to get himself killed, so I gave chase next time, cornered him in a doorway and told him that this was stupid and we shouldn’t be enemies. He was very relieved and immediately offered me a job caricaturing captains of industry for a business publication he edited. I even drew him for one cover. Recently I got a sweet note from his daughter. He was very proud of the picture and the family used it on the programme for his funeral service.

After being sacked as a cartoonist, I washed windows part-time and became invisible. Standing on a stepladder inside a lawyer’s office, I smeared suds across a glass pane and wiped it off again while seated below me a distressed farmer’s wife seeking divorce detailed her husband’s depraved sexual demands. A former flatmate could see me all too clearly. ‘Locky’ Smith, now Sir Alexander Lockwood Smith, former Speaker of the House of Representatives and former High Commissioner to the Court of St James’s, told me he did sudden U-turns in his car when he saw me trudging the streets with my ladder and bucket because he didn’t want to hurt my feelings by whizzing past in his brand-new Ford Escort. That’s compassionate conservatism for you.

I also wrote and produced my last capping revue, starring my friend, Peter Hayden, who went on to become an award-winning presenter and producer of wildlife television documentaries, both here and overseas. Latterly, at an age when most people are taking fewer career risks, he chanced his arm at acting full-time and has made a success of that as well.

The revue also starred a very pretty, super-bright social-sciences student, Christine, who became my first serious girlfriend. When Palmerston North Hospital opened a separate psychiatric unit and called for student volunteers to work night shift, we both applied and made the cut, with about ten other students. The first television drama I ever wrote, Inside Every Thin Girl, was based on an anorexic patient we befriended—Peter Hayden starred as one of the student volunteers.

Early evening, they locked us in with the inmates and unlocked the doors the following morning. We made toast and cocoa for patients who couldn’t sleep and played endless games of table tennis to keep ourselves awake. Apart from one young man smearing his faeces on the wall, nothing untoward ever happened.

The front-door buzzer sounded after midnight one night. When I went to check who it was, my father was swaying drunkenly in the security lighting. We talked awkwardly through an intercom.

‘Egghead, I’d like a job here. I could do this.’

‘It’s not up to me, Dad,’ I replied politely. ‘You’ll have to talk to the hospital authorities.’ He nodded and weaved off into the darkness.

As you’d expect, there was less of a stigma against mental illness in such an institution—the threshold for going loopy was much lower. The senior staff seemed to take it in turns having breakdowns of one kind or another. Mild cases were called ‘acting out’—they sought sedation and were put in a room with a ‘do not disturb’ sign on the door. I was always tempted to add in felt pen ‘disturbed already’. Others had full-blown psychotic episodes, which meant one of two things—either they were never coming back, or rapid promotion.

The occupational therapist was on leave after a nervous breakdown. Word got out that I could draw. With no training whatsoever, I was promoted to acting occupational therapist and put in charge of twenty patients, half of whom were schizophrenic, which made it 30 patients in total (just joking). It could be challenging. If you gave them playdough or clay they tended to make erect penises, and you had to give them positive feedback without looking perverted yourself. Not having a clue how to weave a basket and desperate to keep them therapeutically occupied, one afternoon I put John Lennon’s haunting, post-Beatles, primal-scream album on the turntable and asked them to draw what they felt. The first track was ‘Mother’. Big mistake!

Over metronomic, thudding-heartbeat drumming, Lennon started wailing plaintively that his mother had left him but he had never left her, and that he wanted her but she never wanted him. Yes, I thought, nodding my head in time. This is great! Then I heard something else. It was quiet at first, then built in intensity. A low moaning accompanied by gentle swaying, which I interpreted as a good sign until it escalated rapidly into banshee wailing, howling and slapping of foreheads. I quickly lifted the needle off the vinyl as staff came running from all directions.

‘What happened? What’s going on?’

‘I’m not sure. Something set them off …’

At a staff meeting one morning, with Christmas Day just a few weeks away, I suggested that I might get the patients to help me make a Christmas cake.

‘What are you going to bake it in?’ smirked the head psychiatrist. ‘The kiln?’ He started shrieking with laughter, which obliged the rest of the staff to nervously join in. I wondered then if mental illness might be contagious.

My relationship with Christine got a whole lot more serious when she became pregnant. We got married in a park and had the reception at our flat. Tom Quinlan was my best man. Having set a precedent with my twin sister’s wedding, my father did not attend.

I WORKED IN THE FREEZING works one final summer while looking for a job that matched my exceedingly lacklustre qualifications. The School of Occupational Therapy in the Central Institute of Technology in Petone needed a tutor in physiology. Provided no one else bothered to apply and they were desperate, I had a slim, long-shot, outside chance of getting it. I drove down for the job interview in my brother Michael’s ‘Noddy car’—a cute Morris Eight Sports.

Michael was a mechanical wizard. When we lived in Owen Street we shared a big bedroom. I kept my half spotless—operating-theatre hygienic. You could safely eat a meal off every surface. His side was a pigsty. Guitars, amplifiers, greasy tools and smelly clothing were scattered everywhere. I had to step carefully around engine parts soaking in trays of oil to get to my bed. I only complained on one occasion and learned my lesson.

‘Look, Tom, I find your anal-retentive ways deeply offensive. Your obsession with neatness and order drives me mad, but have I ever grizzled and complained? No! Out of respect for you I have kept these feelings to myself.’

There was a lot of our father in him as well.

When I was contemplating purchasing a motor vehicle, I naturally sought his advice. He was soaking in a bath at Owen Street. I had to invade his privacy because he could be in there for hours. Not that it made much difference—the grime just seemed to swap pores. I told him it was a Ford Prefect and was going to cost me 60 bucks. He whistled softly.

‘I dunno, Tommy … My Ford only cost ten dollars and it goes like a dream. The Buick cost fifteen dollars and only needed new spark plugs. The Morrie Eight is perfect and only cost twenty dollars. I’ve always said—pay more than twenty bucks for a car and you’re only buying trouble …’

I was tootling along in his Morris Eight when I encountered a torrential downpour coming down the Ngauranga Gorge, turning the snaking descent into a nightmare luge run. The canvas top started streaming water and the single windscreen wiper, which provided a small wedge of visibility, stopped working. The car’s designers had anticipated this might happen and thoughtfully provided a tiny lever on the inside of the windscreen that you could use to manually operate the wiper. With one hand on the wheel, the other hand throbbing from the effort of creating a clear triangle in the deluge, I slid down to the Hutt Motorway, buffeted, rocked and sprayed by cars and lorries thundering past me. What was I letting myself in for?

Even the name—Central Institute of Technology—sounded like one of those asylums the former Soviet Union maintained high in the Arctic Circle exclusively for dissidents. There were times when it felt like it. But the students, all female, not much younger than me, were sweet and lovely. There were some awkward moments. When a very pretty girl asked, ‘Please, sir, what’s an orgasm?’ I blushed crimson, which I hadn’t done for ages, and told her to see me after class. Much to my relief when the bell sounded she was the first person out the door, which suggested she knew the answer and was winding me up. The staff were also lovely. Mostly spinsters of a certain age, they made a huge fuss of me, the only male on the staff. The head of the school had a leg so withered by polio it had to be encased in a plaster sarcophagus painted in flesh tones. Quite literally a drag, she had to heave it along as she walked. It struck things and was cratered and scratched. Tall and pretty, she lived with her mum and her cats. When her mum died she killed the cats and took her own life.

I knew how she felt. Sitting in my small office overlooking the playing field, watching seagulls wheel overhead, trying to plan lessons with a mountain of essays at my elbow waiting to be marked, I couldn’t escape the feeling that life was passing me by. We lived in Eastbourne. On the bus home the words from the big hit of that year, ‘A Horse with No Name’ by America, kept repeating themselves in my head, about how good it felt to be out of the rain.

Except it was still raining, the Morris Eight had died and we didn’t know a soul. Our small downstairs flat had been built into a bank at the rear of a house by our landlord, who lived upstairs. There was hardly any natural light. The only view was of concrete-block retaining walls. We had no television set and precious little furniture. It was worse for Christine—she had a brain the size of Africa, was stuck in the house all day and was heavily pregnant.

SHAUN WAS BORN ON THE seventh day of the seventh month of 1972. He was beautiful. I floated more than walked back to CIT in Petone in the soft morning light for my first lesson of the day, vowing that I would be the best father ever for him. I fell short all too often and in middle age tearfully confessed this to my mother, fully expecting her to take issue with this harsh assessment, or at the very least say something neutral yet vaguely consoling, like ‘You were very young, darling, and you did the best you could.’ Instead she swooped like a bird of prey spotting a lost lamb. ‘Dat’s right, ye were! Ye were a piss-poor father to dat poor boy!’

Most lunchtimes I took sandwiches or bought a pie and walked from the CIT campus to the windswept Petone foreshore, where seagulls huddled together for warmth, and stared longingly at the glittering capital city across the water. I felt like Nelson Mandela staring across at Cape Town from the prison rock of Robben Island. Apart from him being locked up at night in a small, damp concrete cell, sleeping on a straw mattress. Apart from him breaking rocks in a lime quarry by day without sunglasses and suffering permanent eye damage as a result. Apart from being allowed only a handful of visitors and denied access to newspapers. Apart from being denied permission to attend the funeral of his mother or his first-born son. Apart from being subjected to verbal and physical abuse from some Afrikaner guards—apart from all that—our experiences were identical.

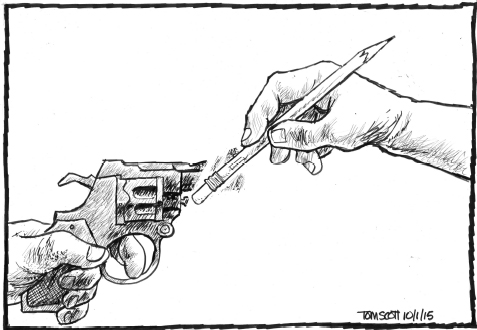

One of the biggest thrills of my life was giving the after-dinner speech at the one-hundredth anniversary celebration of the Parliamentary Press Gallery in Wellington’s old Town Hall, at which Nelson Mandela was the guest of honour. Earlier in the evening a high-school choir sang South Africa’s new national anthem ‘Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika’ beautifully and Mandela thanked each girl in turn, shaking their hands warmly as tears streamed down their faces. I got to present him with framed originals of two of my cartoons—one I drew on his release from Robben Island, the other I drew the day he became South Africa’s first post-apartheid president.

The dinner was a great coup for my mate, chairman of the Press Gallery organising committee and private-radio titan, the gravel-voiced Barry Soper. Barry’s contacts are so good he is able to report accurately what some politicians mumble in their sleep. When he heard whisper of a possible Mandela state visit to New Zealand, faster than the speed of light Barry dispatched a dinner invite via the ANC in Pretoria long before the apparatchiks who arrange such state visits at this end had even thought about their first gin and bitters for the day. Mandela consented partly as a thank you to the role the New Zealand news media had played in the struggle against apartheid. Foreign Affairs, Internal Affairs and the Prime Minister’s Department grizzled into their riesling at being gazumped.

After their regular Wednesday interview in his ninth-floor office, a peeved Jim Bolger asked Barry to travel down in his private lift with him. (Prime Ministers have one for their exclusive use.)

‘Look, Barry, I really think someone of my stature should introduce Mandela.’ Barry said he’d get back to him. He did. The answer was no.

To be fair to Jim, he did lead the fight against the 1981 Springbok tour inside cabinet, persuading almost every minister, bar Prime Minister Rob Muldoon and maybe one other, that the rugby equivalent of coitus interruptus needed to be practised. Being outnumbered twenty to one was tantamount to a draw in Muldoon’s book so, using his casting vote, the tour carried on. To their collective shame his cabinet colleagues maintained a sullen silence in public.

When Mandela died it was galling watching assorted dignitaries and luminaries scrambling for a seat on the RNZAF flight taking Prime Minister John Key to South Africa for the state funeral—none of whom I remember being part of the handful of protesters outside the Hutt Recreation Ground when a white South African team participated in the World Softball Champs in 1976. Ever so politely, the cops requested we move away. A dashing, romantic figure leaped on to the deck of a truck with a loud-hailer and in a fiery speech condemned jack-booted Gauleiters and the creeping fascism of the police state—it was the fledgling poet Gary McCormick, barely out of primary school. Nor were they in the bedraggled huddle outside Athletic Park, mumbling ‘Amandla! Awetho!’ while thousands of Pākehā males streamed into the ground to watch the trials for the 1976 All Black tour to the Republic, some of them yelling out to me in passing, ‘Why are you with those commies and homos, Tom?’

It was a fair question. I asked the eternally reasonable Halt All Racist Tours (HART) leader, Trevor Richards, who was standing near me, if he ever felt like chucking it in. He shook his head and smiled benignly under his bushy walrus moustache. He replied that the massive crowd pouring past us were ill informed, on the wrong side of history, but essentially decent. They would see the light one day. That’s how he spoke, and he was right.

When John Key was asked what his stance on the 1981 Springbok tour was in a televised leaders’ debate with Helen Clark during the 2008 election—which he went on to win handsomely—he could only manage an uncomfortable, sickly smile and the feeble claim that he couldn’t remember, which is about as plausible as being a sentient adult on 20 July 1969 and later claiming you couldn’t remember the moon landing. No one would have held it against Key if he had admitted to being a young snot-head in favour of the tour. He would have earned even more points still had he invited Trevor Richards and John Minto to travel with him to Mandela’s funeral, up the front in the VIP section of the Air Force plane.

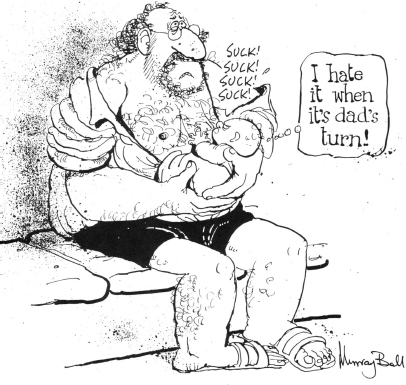

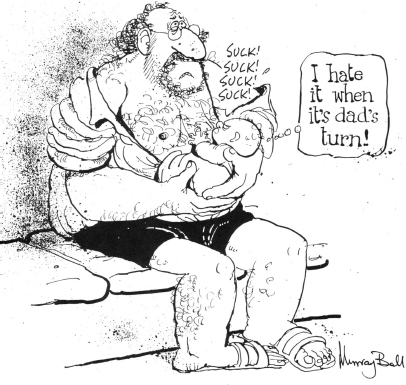

WHEN CHRISTINE WAS OFFERED A good job with the University Students’ Association in Wellington I quit my job at the CIT and became a full-time househusband and child-minder. With or without ovaries, no one knows how demanding and lonely a task this can be until they have done it for eight hours a day, five days a week, for months and months on end. How my mother coped with my sister Sue and me in London on her own I’ll never know.

At times, I zoned out playing with Shaun and would break out of a daze to find him staring at me curiously. How long had I been silent, I wondered. And was this why he was slow to talk? He said ‘Mum’ and ‘Dad’ and a few other simple words but was essentially monosyllabic. We were worried sick. It turned out he was biding his time. One lunchtime, I was offering him something or other, and in a surprisingly deep voice for his age, he said slowly and deliberately, ‘Actually, I would prefer …’ ‘Actually’ was actually his first word in his first actual sentence. He started calling me ‘Tom’ shortly after this. When I asked why this was the case he looked at me as if I was stupid. ‘Everyone else does!’ I had to accept that.

When he had his afternoon naps I raced to the dining-room table and drew cartoons for HART News, for no fee of course, wondering when a real cartooning job would come along. Bounding up the stairs to the HART offices one day I heard music that I had never heard before, yet I recognised immediately. One of the few joys of the CIT was having the library on the same corridor as my office. I ducked in to read copies of Newsweek all the time. One issue raved about a sensual, hallucinatory, mystical, jazz/blues/rock album by an Irishman who sang with a singular intensity and urgency. I burst into the room. A singer was howling about venturing in the slipstream between the viaducts of someone else’s dream and being born again. It was Celtic mumbo jumbo. It made no sense and it made perfect sense.

‘This is Astral Weeks by Van Morrison!’ I shouted excitedly. They couldn’t confirm it. It was on the turntable when they arrived and they had just pressed repeat. I reached for an album cover I had never seen before. It was Astral Weeks. This song was a sign.

I was about to be born again.

The capital enjoyed two daily papers back then. The Evening Post cartoonist was the legendary Nevile Lodge. He had been there so long he qualified under the act as a living fossil. His Sports Post covers of All Black test matches were rightly famous. Astonishingly, they came out on the same day as the game. You could listen to the test match on the radio in the afternoon, go to the flicks at the Regent in the evening, head for the pie-cart in Feilding’s square close to midnight and be intercepted by a paper boy yelling ‘Sports Post! Sports Post!’ and there would be Nevile’s cartoon on the cover of a kiwi and a springbok locked in titanic battle.

I have kept up his tradition, but I was never a big fan of his drawing style or stolid view of the world. He was a testy curmudgeon long past his best when he finally retired and I replaced him on the Evening Post. Come to think of it—I am close to that age now and must make more of an effort to wear revolving bow-ties and break into song-and-dance routines when I enter the controlled anarchy of the newsroom … Come to think of it—they don’t have newsrooms any longer, just hushed workstations and the low pinging of computer keyboards. (I only ever heard the fabled cry of ‘Stop the press!’ once. It was the morning of the stock-market crash of 1987. I was dropping off one of my first cartoons to the now departed Evening Post when the editor, Rick Neville, came running out of his office and yelled it out across the stunned newsroom, then, snatching an old manual typewriter, began pounding out the front-page lead himself. It was very impressive.)

Nevile Lodge can be excused some of his gloom—he spent the best years of his life behind wire in a concentration camp, as did Sid Scales, the much-loved, long-serving cartoonist on the Otago Daily Times, and the great British cartoonist/illustrator Ronald Searle. The wonderfully whimsical Carl Giles and the celebrated, hard-nosed American editorial cartoonist Herblock (Herbert Lawrence Block) both began their illustrious careers as war artists. Pulling on rectal gloves and inserting your hand up a cow’s bum at vet school hardly counts.

Eric Heath, the cartoonist for the Dominion, was a kind man of sunny disposition so it’s hardly surprising his cartoons lacked edge. He was a terrific painter of marine life but I was not a fan of his cartoon drawing style or his choice of subject matter. It was too domestic—trolley buses, cats trapped in trees and impish politicians. N.A. Nash would have loved him. To my haughty gaze, neither Eric nor Nevile could caricature politicians very well. I get disproportionately irritated by cartoonists identifying people they are drawing by using names on clothing, briefcases, desktops or doors—it’s a device we all employ from time to time when a person is not well known. When I resort to it I end up irritating myself.

I grew up adoring the economy of line of the great Mort Drucker, who captured faces perfectly in Mad magazine’s movie parodies. I also loved the spidery line and the assured crosshatching depictions of writers, artists and politicians of David Levine in The New York Review of Books. Our very own Dunedin-based Murray Webb is one of the few cartoonists in the world to approach Levine’s genius. I also admired the savage, jagged strokes and splattered ink of Gerald Scarfe and Ralph Steadman, who distorted politicians’ faces to grotesque proportions while keeping them recognisable. And I have long been a fan of Bob Brockie’s wry, eccentric doodles in The National Business Review. His drawings in Victoria University capping magazines in the 1960s were a huge inspiration to me.

When Labour won the 1972 election and Norm Kirk became prime minister, none of the nation’s cartoonists could draw him properly. There was something elusive about him. Like an explorer in a pith helmet searching for the source of the Nile, I went looking for the essence of Norm Kirk. I spent days, then weeks at my drawing board, growing weaker and weaker from hunger and thirst. I know memory is an unreliable thing but I’m pretty sure I came down with full-blown malaria and had a touch of dengue fever at one point (the same phenomenon occurred when my deadline loomed for Listener columns, then magically disappeared the next day). I began wondering if I should abandon this foolhardy, nightmare quest, when voilà! Norm appeared on the paper before me. Even now I am proud of this drawing, though the poor lettering in the speech bubble displeases me still. It was streets ahead of what everyone else was doing at the time and too good to waste on HART News—assuming they’d want it. Then I remembered that the Post and the Dom were not the only game in town—there was also the Sunday Star. Should I pay them a call?