BACK IN WELLINGTON THE FOLLOWING Monday, I braced myself for my first ever prime ministerial press conference. It hadn’t been possible earlier because Norm Kirk had been absent overseas or convalescing after varicose-vein surgery. At the appointed hour the Press Gallery trooped upstairs to the Prime Minister’s suite on the third floor of the old Parliament Building and loitered nervously in the marble and columned foyer like novitiate priests waiting for an audience with the Pope. I never saw this degree of caution with any other Prime Minister. With Lange there was always excitement, and with Muldoon apprehension, but nothing on the scale Kirk induced.

Twenty minutes of low, stilted conversation took place before we were ushered down a gold-carpeted corridor and allowed into a large office with windows that looked down on a drab internal courtyard with olive-green walls. It reminded me of Colditz. The windowsills were carpeted in pigeon droppings.

We waited silently in this room, notebooks, tape recorders, lights and cameras at the ready, for quite some time before a door at the back of the room opened and a big man entered and shuffled slowly to a huge brown desk, where he lowered himself gingerly into a chair. He had one foot in a large, shiny, black leather shoe, the other in a sock and sandal.

I had never been this close to him before. I was shocked by his appearance. You didn’t need half a degree in veterinary science to see that this man, if not terminally ill, was close. He was chalky white. His hair was plastered to his temples by sweat. It wasn’t a hot day and he was the only person in the room perspiring. When people asked questions he spoke so slowly and the gaps between sentences were so protracted there was room for whole separate conversations, had anyone dared.

At the finish, Ian Templeton from the Auckland Star, a dear man and shrewd journalist with impeccable sources, rose and said, ‘Prime Minister, I’d like you to meet a new member of the gallery.’ I approached the Prime Minister’s desk and put my hand out to shake his. Wearily, he raised his giant hand off the desk. It was damp and limp.

Outside in the safety of the corridor I expressed an alarm that none of the other reporters seemed to share. Kirk’s health had been deteriorating slowly and inexorably for so long the gallery barely registered the decline any more.

I never saw Norm Kirk at anywhere near full strength, but even unwell he was a commanding figure in the House. His mere presence seemed to charge the air of the chamber with a strange tension and expectation. He always entered the floor of the House through the side door and they were especially grand arrivals, as he did so behind an escort of shorter colleagues. He would pause to joke with people like Joe Walding. Even when in considerable pain he would reach his bench grinning broadly, and before taking his seat he would turn and give an exaggerated wink to those in the back rows behind him. It was a performance of a captain telling his men they had nothing to worry about.

If he rose to speak he was granted an immediate respectful silence. Few dared to interject. Even Muldoon was cautious. Members from both sides of the House sat up straight and paid close attention to what he had to say. Should he begin to shout, the Press Gallery filled to overflowing as if by magic. Reporters denied desks to write at would stand about exchanging grins, happy just to share in the excitement.

Kirk never warmed to the concept of journalists looking down on politicians—he thought it should be the other way around. Journalists should cover Parliament from a deep pit in the floor. I’m glad this never happened. Imagine the shock of looking up a cabinet minister’s nostrils and seeing nothing but daylight.

The only other parliamentarian who could pull a crowd like Kirk was David Lange, whose press conferences in the Beehive theatre were must-see events. There was a suspicion that numbers were swelling due to senior civil servants sneaking in to catch the vaudeville.

As Kirk’s health deteriorated his triumphant entries into the chamber became less and less frequent. His last lap began with varicose-vein surgery in April 1974. Eager to return to work, he denied himself an adequate recovery period and complication followed complication. As his strength eroded, so did party morale. Kirk felt this keenly and in private he would rage at the terrible fatigue that dogged him. He took to shooting the pigeons soiling his windowsills with an air rifle, contributing to rumours that he was half martyr and half fruit loop.

Not long after the Labour Party conference where Kirk had castigated the news media, Inquiry reporter George Andrews met him in the car park beneath Parliament. Laden with a couple of briefcases and some notes, Kirk moved with a slowness that was painful to watch. George plucked up the courage to offer assistance. Kirk shook his head. ‘George, I’ll carry these bloody things even if it kills me.’

In June he was cleared for full duties but this failed to quell growing public anxiety. Aware of the wild conjecture, Kirk joked grimly with reporters following minor surgery to treat an ingrown toenail that the same incision had been cunningly used to remove assorted cysts, growths and cancerous tumours.

On 28 August, Kirk entered Our Lady’s Home of Compassion in Island Bay for complete rest. The next day, at a parliamentary reception for a visiting sports team, I grilled junior government whip Jonathan Hunt on the real state of his leader’s health. Jonathan was more interested in dropping hints about a big story he was intending to go public on the following week, and assured me loftily that the Prime Minister was on the mend.

Kirk died two days later, on Saturday, 31 August, after a seizure. He was 51 years old and had been Prime Minister for barely 21 months.

The week after his death was the most extraordinary I ever witnessed on the Hill. Rain began falling constantly in the capital, and with it came a cloudburst of grief of stunning intensity. That grief, like the rain, seemed to endure for about a week, then abate as suddenly as it had come.

SORROW IS LIKE A SPLINTER in the heart, and I have often wondered if Labour would have fared better in the ’75 election if a little piece of the splinter had been left in place and wiggled at appropriate moments, or if they had called a snap election straight after Kirk’s death, when the grief was the size of a vampire stake.

Instead Labour were desperate to paint a picture of business as usual, and put Kirk behind them—as if his death were of no great consequence. He was hardly mentioned by Labour on the hustings. Significantly, on the campaign trail in Rotorua, Rob Muldoon made a well-publicised detour to pay his respects to Kirk’s widow, Dame Ruth. If there was any legacy to tap, Muldoon wasn’t going to pass up the opportunity.

After Kirk’s death, his government driver told me a sad story. Very near the end of his life, Kirk had an engagement at a Catholic school in Palmerston North. Several times on the two-hour drive from Wellington they had to stop for the Prime Minister of New Zealand to get out of the car, lower his trousers, squat on the side of the road and purge himself of bloody diarrhoea. Pale, shivering and humiliated, he got back into the LTD apologising profusely. What struck the driver was how alone Kirk was.

Kirk’s death came as no surprise to his driver. I learned through a terse, jarring Sunday Star headline: ‘KIRK DIES AGED 51’. I read it over and over again in disbelief. I hurried down to Parliament on Monday morning, pen and notebook at the ready. In the marble foyer there was an air of hushed, reverent chaos. Workmen in shorts and boots had been there since four in the morning making preparations for Kirk to lie in state. They jostled for space with messengers and television crews. Outside on the concourse, a crowd began to assemble quietly. As the hearse drove up the first strains of a Māori lament moved the base of public grief from one of polite containment to one of free expression. Then Pacific Island groups started singing soaring hymns. Polynesian New Zealand began acting as a catalyst and poultice for diffident Pākehā sorrow. Anyone within hearing distance who had any feelings on the matter could feel them being tugged to the surface.

Norm Kirk’s body in its huge coffin was placed in the foyer of Parliament with a New Zealand flag draped over it and potted ferns placed around it. Soldiers from all the forces stood at attention at each corner, their rifles upside down. People queued well into the night, three nights in a row, in steadily falling rain, for a chance to pay their respects. Some brought young children with them, awestruck and silenced by their parents’ grief. A few asked hushed questions.

‘What are the soldiers doing, Mum?’

‘They are changing the guard, Michael.’

‘Is that anything to do with Christopher Robin?’

‘No, dear, it has nothing to do with Christopher Robin.’

When I enquired why they had brought their kids out at such a late hour in such bad weather, the standard response was that this was a piece of history. They wanted them to pay their respects and say goodbye to a great man who would be talked about and remembered for many years.

That hasn’t been the case. Kirk slipped off the radar relatively quickly and is seldom mentioned now. The scale and the depth of the mourning for him forced many commentators into new assessments of the man, but this frenzy of postmortem punditry—I indulged in it myself—died away with the subsidence of the unprecedented sorrow.

That sorrow subsided faster for some than for others. I stood watching mourners file past the coffin for the best part of a day. I was there when Kirk’s Labour Party colleagues came to pay their respects. The queue had slowed and a small bunch of them paused within earshot. They were grinning and delighting in the fact they had the numbers to ensure that Kirk’s deputy, Hugh Watt, wouldn’t become leader. With Kirk lying just a few feet away, there was something shocking and harsh about their pragmatism.

I was still there when it was Sir Keith Holyoake’s turn. He stood in front of Kirk’s coffin booming, ‘Farewell, Norm, farewell!’ He wasn’t being theatrical or attention-seeking. There were tears in his eyes. It was a genuine and touching salute to a respected political opponent. Sometimes it is easier to pay tribute to a fallen foe than your own comrades. The French have a saying that no man is a hero to his valet.

On the Tuesday afternoon the House paid tribute to the fallen Prime Minister. Three of the most moving speeches came from Opposition spokesmen. ‘Fifty-one,’ said a pale Brian Talboys, ‘is too young to die.’

‘I find it very difficult to accept that the big man will not walk through that door and enter this chamber again,’ said Holyoake.

‘He graced the office of Prime Minister,’ said Jack Marshall, adding, ‘We treated each other with mutual respect, which is probably mystifying to our more rabid supporters.’ Through all the implied rebukes, Muldoon stared sourly straight ahead.

Kirk’s coffin was so heavy the pallbearers almost lost control carrying it down Parliament’s steep steps. It lurched forward and they had to step quickly to keep up with it. He was loaded into a hearse, driven to Wellington airport and loaded with full military honours into the belly of a Royal New Zealand Air Force Hercules, which is probably still flying today. They took off in a terrible storm bound for Timaru, the closest airport to Waimate, where he was to be buried. The weather was so bad Timaru airport was closed, and the Hercules was forced to turn back to Christchurch. The coffin was swiftly unloaded and without ceremony shoved into the back of a revving hearse, and with one police car in front and another behind, the funeral cortège accelerated south into the lashing maelstrom. My locking partner from social rugby, Phil Melchior, a reporter for NZPA, and other pool journalists followed in two additional cars. Through whipped-up spray and sheets of rain they chased screaming sirens and flashing red lights. Police on motorbikes blocked off side-roads as the convoy hurtled south, well in excess of the speed limit, to get to the Waimate cemetery before nightfall.

Phil told me that racing through small country towns was quite off-putting. Local radio stations had reported that the Prime Minister’s body was coming. Heads bowed and hats removed, citizens lined main streets that had become shallow lakes. Not slowing, the convoy raced past, sending up walls of water like Moses parting the Red Sea. Mourners would have seen very little and been left drenched.

They got to Waimate cemetery just as the rain eased off and the last rays of the setting sun struck the burial plot where the Prime Minister was finally laid to rest. Almost as soon as the earth hit the top of his coffin, the Labour Party began pretending he never existed. They didn’t know it yet—no one did—but their re-election chances were being buried with him.

IN JULY 1975 I WAS wildly excited as well as nervous when Qantas offered to fly me to Australia as its guest on its inaugural flight from Sydney to Belgrade, in what is now Serbia. Apart from one trip to Auckland and back on an Air New Zealand flight, still within sight of land, I had never left New Zealand soil.

I didn’t possess a passport. When I applied, I found to my dismay that I wasn’t entitled to one. I arrived here as a toddler and it was remiss of my twin sister Sue and me not to correct our parents’ oversight and apply for New Zealand citizenship the instant we stepped off the gangplank. At the age of 28 I had to traipse to the British High Commission in Thorndon with my birth certificate in exchange for the dubious glory of a United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland passport—which for years to come put me at the head of the queue should a plane get hijacked and they started executing passengers.

Back then the first Boeing 747s with their distinctive bubble were just starting to roll off assembly lines in Seattle in huge numbers. With the onset of the jumbo-jet age, passenger numbers soared exponentially as well. New Zealand, once described by Rudyard Kipling as last, loneliest and loveliest, all of a sudden seemed closer to the rest of the world. I wrote at the time:

Does constant rubbing of the shoulders with people draped in Spanish leather, Italian suede, French velvet, American denim, English check, Mexican saddle cloth, Bolivian llama hide, Japanese silk, Bali batiks, Indian saris, Mao tunics and camouflage jackets from the Indochina war zone tend to put you, in your Hugh Wright’s winter clearance sale viyella creams, a little on the defensive? When others talk of lovemaking with beautiful strangers on the Côte d’Azur, moonlight poetry readings at the Acropolis, being shot at by rebel tribesmen in Iran, more fornication in Vienna, dysentery in Damascus, alcohol poisoning in Munich, still more fornication in Rome and broken axles in Islamabad, do you keep your slap and tickle stories from the Foxton sand dunes to yourself? Do you also automatically assume that people are no longer interested in the time your scooter broke down in the rain opposite the Palmerston North gasworks?

If you do, you are suffering from what my sophisticated friends call OE deprivation. OE, of course, is the abbreviation for overseas experience—and no New Zealander, it is claimed, is complete without it. As well as being vital to emotional, intellectual and sexual development, OE very nicely fills that awkward gap between high school and marriage. In fact, OE must be pursued when young and is often used to force reluctant partners into marriage or as compensation when marriage plans fall through …

My sophisticated friends using the term ‘OE deprivation’ were in fact only one man, John Muirhead, my chum from Masskerade and Chaff days. I have falsely been given the credit ever since. Things even out.

In another Listener piece I wrote that when New Zealanders moved to Australia it raised the IQ of both countries. Muldoon helped himself to this line at a press conference a week later and it has been cited for years as proof of his droll genius. My joke! I have no real cause for complaint—I had refashioned it from a Will Rogers line in the first place. Besides, I was chuffed that Muldoon was reading my columns.

The Qantas trip could not have come at a better time. Another old chum from Massey, Greg Bunker, then earning a king’s ransom prescribing pills to pampered poodles in Manhattan, put it best when he warned, ‘At your present rate, you’ll get here playing mah-jong on the sun deck of the Mariposa.’

I was a nervous traveller. Getting out of the Manawatū was a wrench. So what if the world was my oyster? With my luck I would be allergic to shellfish.

It helped that in Sydney all the journalists on the Belgrade junket were given a guided tour of the Qantas base at Mascot. When I discussed safety issues with a man from Qantas he said I had nothing to fear—my worries about flying were groundless. I said it was the groundless bit that worried me. To demonstrate the principles of flight, he blew across a piece of paper. ‘There,’ he said proudly, as the far edge rose, ‘the Venturi effect—that’s what keeps these seven hundred thousand pound babies forty thousand feet aloft.’

Shortly after take-off, most of the press party had managed the spiral staircase to the Captain Cook lounge in the bubble. Before we had left Australian air-space, they had drunk the bar dry of beer. It was thirsty work flying for hours over parched sand and rock, albeit hidden in inky blackness far below us. Then they uncomplainingly switched to spirits and that was all gone before we reached Singapore. It was my first exposure to the Aussie media and you couldn’t help but love them.

Apart from Australia, which barely counts, and Singapore, which was just a stopover, the former Yugoslavia was the first country I ever visited. Much like a duckling or gosling believing that it is the same species as the first living creature it sees on hatching, I imprinted on Yugoslavia. I want to return to Lake Bled and Dubrovnik and take Averil with me. George Bernard Shaw once said that if there is a heaven on Earth, it is Dubrovnik.

I came close to heaven when I played in a doubles match on clay in Dubrovnik with the great John Newcombe, Ken Rosewall and Rod Laver. I partnered ‘Rocket’ and it was largely thanks to his speed around the court that we won the first set seven games to five. We were no match for Newcombe and Rosewall in the second and third sets, however.

The match was played on a private court in an exclusive suburb of Dubrovnik before a highly partisan but surprisingly knowledgeable crowd consisting of two ball boys, a whitewash-application man and a suspicious head groundsman. They watched us in contemptuous silence. The tennis wasn’t worth keeping an eye on, but the hired sandshoes and expensive hired racquets were.

I should point out that for the purposes of the match I was Tony Roche, and my new Aussie mates played the other Aussie tennis greats. We had to stay in character the whole match. I should have been completely outclassed, but being Tony Roche for the morning I lifted my game to previously unscaled heights. In short, it was the most enjoyable tennis match I have ever played.

I was impressed with the Australians’ ability to weave and sustain an elaborate schoolboy fantasy. It eventually got to the stage where Rosewall began to argue with an imaginary linesman, and Newcombe began shouting his hotel room number to imaginary girls in an imaginary crowd. The whole trip, the guy playing Newcombe had only one answer when you asked him how he was: ‘I’ll be OK, mate, when I’ve had a root.’ When we drove through the streets of Zagreb in a bus he crouched at the front like Queequeg, the harpoonist in Moby Dick, spotting attractive girls and awarding points out of ten. ‘Nine pointer on starboard, boys! Holy fuck! Eleven pointer on port!’

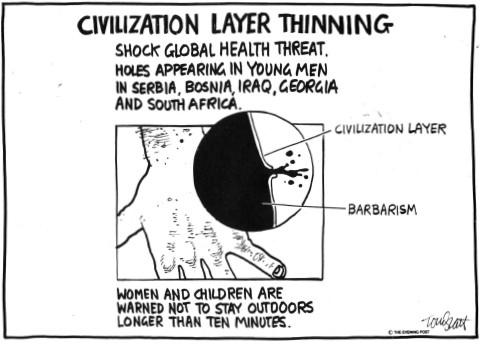

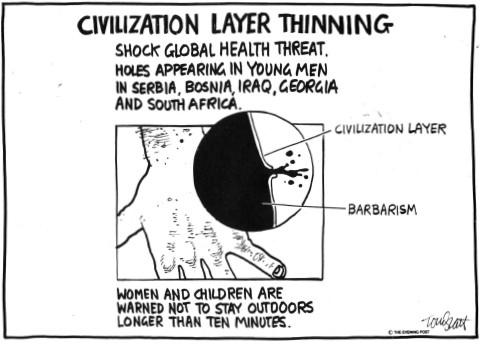

Watching the news fifteen or more years later, it was horrifying seeing beautiful landscapes and glorious medieval towns that had seemed calm enough to our naive gaze descend into sectarian violence, ‘ethnic cleansing’ and a genocidal barbarism unmatched since the charnel houses of World War Two. I did some of my better cartoon work on this more recent bloody chapter in European history.

If you want to be sickened again, read Slaughterhouse: Bosnia and the Failure of the West by David Rieff. He recounts a chilling moment for members of my generation in particular, who believed in the redemptive power of music, where Serbian troops head off for another day of rape and butchery with Bob Dylan blasting through their Sony Walkmans.

I DIDN’T TAKE THE QANTAS flight back to Sydney with the other journalists. Instead I flew on to London, where I hung out with friends on Fleet Street and spent an afternoon in the Press Gallery in the British Houses of Parliament. It was hardly an in-depth investigation, yet when I got back to New Zealand, fighting back tears when we descended over the Marlborough Sounds on a crystal-clear morning towards Wellington’s dear rugged coast, Ian Cross decided to put me on the Listener cover. I am wearing the tan suede jacket Christine bought me in China, I am sucking a cigar Winston Churchill fashion, I am saluting, I am wearing a pith helmet, and I am photographed against a large Union Jack. The tagline is ‘Tom Scott and other New Zealanders in London’. Visually it was cheesy overkill and, given the ordinary copy I submitted, quite unmerited, but Ian was determined to milk whatever star status I had. And if I didn’t have any star status he was determined to manufacture some.

To my shame, I was a more than willing accomplice. Over a two-year period either my cartoons or my likeness appeared on the cover of the Listener nine times. There was a head and shoulders photograph, two cartoon versions of me, and five other illustrated covers on subjects as various as the Commonwealth Games in Christchurch and Muldoon’s first prime-ministerial trip to the People’s Republic of China—in which I depicted him striking a heroic, Mao-like pose on a wall poster, in the bottom right-hand corner of which some creature has recently emptied its bladder.

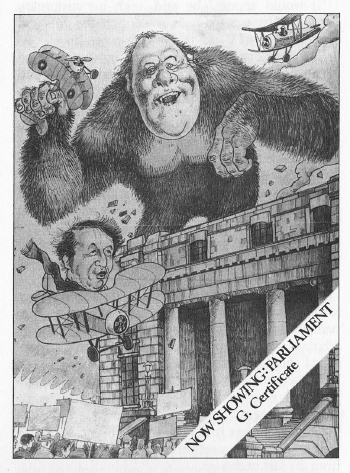

It was very nearly ten covers. Ian commissioned an election-year cover then rejected it as too provocative. I drew a movie poster with a jovial Muldoon as King Kong on the top of the old Parliament Buildings, snatching biplanes out of the sky, while in the foreground an equally jovial Bill Rowling pilots a circling Sopwith Camel. The tagline was: ‘NOW SHOWING: PARLIAMENT. G. Certificate’.

Ian was absolutely right on one thing—the censor’s rating was far too lenient. That year in politics there were scenes of graphic violence, coarse language and naked, full-frontal appeals to greed and fear. Ian could see coming what the rest of us couldn’t—Muldoon was shaping up to overturn Labour’s seemingly impregnable majority, so there was little to be gained depicting the next Prime Minister as a giant ape and pissing him off unnecessarily.

I was the one pissed off. I decided to print it as a poster that would make me rich and teach the Listener a lesson. I ended up with a pile of them in my garage sitting alongside the stacks of unwanted copies of Masskerade 73. They came in handy as gifts and I have only one badly creased copy left.

AFTER KIRK’S DEATH, ON 6 September 1974 the Labour caucus voted for Bill Rowling to be their next leader, with Bob Tizard as his deputy. They were the best choice at the time. It was impossible to dislike Bill, but harder to be impressed by him. With Bob it was the other way around.

During the 1975 election campaign, I was with Prime Minister Bill Rowling when he opened a new gymnasium at a high school in Tokoroa. Afterwards, as people were streaming out, I must have looked lost because he asked me how I was getting to his rally in Taupō that night. In those days, the Listener’s largesse extended to typewriter ribbon, litres of white-out, modest hotel accommodation and airfares, but not rental cars. I replied sheepishly that I was hitch-hiking and he immediately offered me a lift in his LTD. I became wildly excited—here I was, little Tommy Scott from Feilding, riding in the Prime Minister’s limousine!

As we crawled through cheering crowds in the school grounds, a local Highland pipe band formed a guard of honour on either side. Accompanied by the stirring skirl of bagpipes, we swung out onto the street. Heroically they kept pace with us as we gathered speed, almost sprinting in the end, not fluffing a note until oxygen debt kicked in and they fell away one by one.

It was then that I felt a joke coming on that I just had to share with my new best friend.

‘Have you noticed, Bill,’ I beamed, ‘the only two things they pipe out of town are politicians and sewage!’ The car rocked with hearty laughter. I was too busy slapping my thighs and dabbing my eyes to appreciate that it was coming only from me and the snickering driver. My new best friend had gone puce with indignation.

‘Fuck you, Scott! I’ve a bloody good mind to make you get out and walk from here!’

It was in Rotorua that I realised for the first time that Labour could lose the election. We were sitting in the bar next to a steaming hot pool when one of National’s campaign ads came on television. To ringing balalaika music, animated Cossacks danced across the screen. A hook snatched away a ballot box, while a voiceover asked what freedoms were safe under Labour.

All the National Party ads were in this vein—extremely slick, very accomplished for their time and like nothing New Zealand had ever seen before. While undeniably clever, they were also fear-mongering, red-baiting and black propaganda—they should have been slapped with injunctions the first time they slithered out from under a rock.

Rowling’s people came into the bar shortly afterwards. They hadn’t seen the ads and they weren’t particularly bothered—everything was tracking nicely according to the feedback they were receiving. There was just no way the country would vote for Muldoon. Their smugness and naivety were deeply disturbing to witness.

It was a wild, giddy, emotionally charged, high-stakes election. On the campaign trail with Muldoon in Napier I called in to see twin sister Sue. Noticing my jittery state, she enquired gently into my wellbeing. I replied that I was hardly getting any sleep and that I was exhausted. Larry, her husband, whose contracting firm was carting boulders for the extension of the Napier breakwater, put things neatly into perspective for me. ‘Yeah, those fountain pens can get pretty heavy.’

I suggested to friends appalled at the prospect of a Muldoon ministry that they should dress as sweet, demure nuns and pack the front two rows of the Founders Theatre in Hamilton on the night of his campaign launch. When the red light came on indicating that he was being broadcast live into a million homes, they were to rise as one, chanting in unison, ‘MULDOON’S A CUNT!’ But no one listens to me. I also suggested filling a bike pump or water gun of some description with a mixture of cream-style sweet corn and ripe Roquefort or Stinking Bishop cheese and, when Muldoon was in full flight, splattering it across the front of his shirt, creating the impression that he’d just vomited on himself. With a bit of luck this would trigger a chain reaction of projectile vomiting throughout the hall of Monty Python’s Mr Creosote proportions, and the broadcast itself would have to be halted and replaced with a still of the Freyberg boat harbour.

It is now a matter of record that Muldoon never chundered over his own clothing at his campaign opening, but instead went on to win the election in a landslide. There were many reasons for this. The tide had gone out on Labour, National’s election bribes were bigger and better sold, but mostly Rob Muldoon had simply more intellectual firepower, more physical stamina, and was vastly more ruthless than his opponents—which sadly many found appealing. No blow was too low, no taunt too cruel. He had been on the receiving end of cruelty and abuse all through his school days and was determined as an adult to get his retaliation in first. Muldoon would never have offered me a lift. If he had I may not have accepted. What I know for sure is that I would never have dared make that joke.

With Muldoon’s stunning victory, Parliament, already fractious and fiercely tribal, became even more bitter and partisan. Had Rowling stepped down as leader at this point, which Geoffrey Palmer and Bill English did when their governments were heavily defeated, it is hard to imagine Muldoon endorsing let alone enthusiastically campaigning for him to get a top job at the UN—which John Key did unstintingly for Helen Clark after he defeated her.

Shortly after his big win, I met the new Prime Minister in a Parliamentary corridor—always a scary experience. He had a colleague in tow, and as much for his benefit as for mine, Muldoon paused to bark, ‘Ahhh, Scott isn’t it? I read an article of yours in the Listener! I didn’t know you could write!’

A voice, not my own, jauntily and foolishly replied, ‘I didn’t know you could read!’

His colleague grinned. ‘He’s got you there, Rob—’ then instantly regretted it when Muldoon glowered at him. We were both on the outer, though my time in the gulag lasted a little longer.

THE NAME SOWETO HAS A lovely Swahili cadence to it, but in fact it is an acronym for the South West Townships—shanty suburbs for black South African workers, servants and their families that sprawl endlessly across brown barren plains outside of Johannesburg. On the morning of 17 June 1976, Sowetan students gathered in the street to protest the introduction of Afrikaans as the official language of instruction in local schools. Their 20,000-strong peaceful protest was halted in its tracks by ferocious police brutality and murderous fire. The official death toll of young blacks killed by the police was 176. Other estimates put it as high as 700. Less than two weeks later the All Blacks, who were travelling with the blessing of newly elected Rob Muldoon, touched down in the Republic to play a four-test series and provide comfort and distraction for the ruling white minority.

Like many others, I was appalled. I wrote an angry column about a Pākehā student uprising in New Zealand, where an oppressed white majority are subjugated by a brutal Māori minority.

Today Otara still smoulders. Many buildings couldn’t be saved, while others were deliberately left to burn. Soldiers and policemen, ironically many of them Pakeha, cautiously patrol the rubble-strewn streets. The worst of the rioting and destruction have died down now. No one seems to know how many people have died. ‘Well,’ Rangi Nathan, the Minister of Police, told a press conference in Wellington, ‘with Pakeha it’s always hard to tell.’ And the foreign press crews smiled politely.

‘I know you boys have deadlines to meet,’ he continued. ‘If you want an official death count I’d put it at seven. Remember too, one of the seven fell under a tank and the other six died of natural causes.’ ‘Natural causes?’ exclaimed the grizzled API Reuters correspondent. ‘Our information is that most of the dead were shot through the heart at point-blank range!’ The Minister merely grinned. ‘Gentlemen, I put it to you, what is more natural than to die when you’ve been shot through the heart at point-blank range?’

Unofficial sources put the death toll at over a hundred, with the number of wounded running into the thousands. The situation is complicated as Otara has no hospital or morgue of its own. The final toll will depend on what the army and police clean-up units find buried in the corrugated ruins of the three gutted primary schools.

The most vicious rioting in New Zealand’s history lasted over three days and at times spread as far north as Queen St. Often there was no purpose to it as young Pakeha gangs rampaged through the streets, smashing windows and stealing luxury items like television sets, food and clothing. The electrical goods were a popular if mystifying choice as Otara is still without power. ‘Most Pakeha don’t earn enough money yet to pay enough tax to justify such capital expenditure,’ explains Koro Rolls, the Minister of Social Welfare …

I knew Cross would hate it, so I didn’t hang around long when I dropped it off at the subs desk. I am a tireless, fearless warrior for freedom—just not that fearless.

About an hour later I was back in Karori when I got a phone call from Ian, during which he accused me of continually challenging his authority and writing deliberately provocative material that pushed my own point of view rather than mocking the views of others. He said he wouldn’t print it. I said sadly that it seemed like a parting of the ways then. Just as sadly he agreed—adding that I left him little choice. There could only be one editor and he was it. We said goodbye civilly to each other and I hung up.

I wanted to cry. Working on the Listener had become the best thing that ever happened to me. It was too good to be true, it couldn’t last, it was time for things to return to normal. I would go back to teaching or something …

I looked out the window. It had started to snow, something that hadn’t happened in Karori for years. Slowly the valley was whiting out. I cheered up enormously. The symbolism could not have been more perfect—anyone who could be fired and then have a freak snowfall hit seconds later was born to write. That night I was to be the first speaker in Ngaio’s winter lecture series and I hadn’t yet written a speech. That didn’t matter—I could tell them how I had just been dismissed and wallow publicly in my martyrdom. Outside in the snow-blanketed street children wrapped warmly against the cold spun deliriously amongst the falling flakes, shrieking and laughing. I started laughing too.

Later that evening my good friend, the cartoonist Burton Silver of Bogor comic-strip fame, came to pick me up in his battered, rusting, draughty Morris van and we drove cautiously along slushy streets to the Ngaio Hall, wondering how many people would brave the snow, sleet and bitter cold to attend. In the event the place was full of loyal column-readers, little old ladies in the main, one of whom grabbed my arm tightly in her gloved hand and told me proudly she’d driven all the way from Upper Hutt. In this crowd I could do no wrong. There were gasps and anguished angry cries when I told them I had been fired from the Listener that afternoon. I kept them waiting a few moments, then added that Ian rang back 30 minutes later to holler down the line, ‘Damn you, boy! I’m going to print it after all.’ The hall erupted in cheers and relieved applause. Not half as relieved as I felt.