IN THE MIDDLE OF 1976, Speaker Richard Harrison, who liked my columns, called me into his office and poured me a Scotch. Something was preying on his mind. It was a recent conversation he’d had with the Prime Minister concerning Labour’s Colin Moyle. A handsome man with pompadour hair and a Kirk Douglas dimpled chin, Moyle was easily the Opposition’s best performer in the House, fuelling rumours that he would soon replace Bill Rowling as leader, which would not be good news for National. According to Harrison, Muldoon had chuckled and said that was never going to happen. He had the goods on Moyle, which he would reveal when the time was right. ‘When things get heated in the House,’ said a pale Harrison, ‘I think to myself, is this it? And I feel sick. What can it possibly be?’

I didn’t know either, but we would both find out on the evening of 4 November 1976. During a bad-tempered, three-hour debate on the supplementary estimates, and amid a flurry of competing points of order, Muldoon thought mocking laughter had come from Moyle. He responded, ‘I shall forgive the effeminate giggles of the Member for Mangere, because I know his background.’ Ignoring the implied threat, an angry Moyle walked into an ambush, asking if it would be in order to accuse the Prime Minister of being a member of a dishonest accountancy firm. Muldoon, who had been drinking, lowered the boom. ‘Would it be in order for me to accuse the Member of being picked up by the police for homosexual activity?’

Both sides of the House were stunned and sickened by Muldoon’s behaviour. When I checked out Rowling’s office after the House had risen, Moyle was curled up in a foetal ball on a couch, weeping—a broken man. Who knows how things would have turned out had he crossed the floor of the chamber and smacked Muldoon or risen to make a point of personal explanation, as Standing Orders allow: ‘Mr Speaker, I would like to assure the Honourable Member for Tāmaki that he is so physically unattractive he has nothing to fear on my account.’

A year earlier, in a seedy part of Wellington, late at night Moyle invited an undercover policeman into his ministerial car—not a good look at the time. As absurd and as cruel as it sounds today, homosexual acts between consenting adults were deemed shameful, sinful and criminal back then. When the late British actor Denholm Elliott, who specialised in playing sweating district commissioners, died of AIDS, his widow was asked how this could have happened. She responded cheerfully, ‘Having a bloody good time, I imagine.’ Incapable of such sangfroid, Moyle offered three differing and increasingly tortuous explanations. In the wake of an official inquiry that scolded him, he resigned his safe Mangere seat so he could contest it in a by-election and return to politics with a fresh mandate. Under pressure from his own party and under intense media scrutiny, he subsequently pulled out of the by-election. The candidate nod went to a human dirigible in a black kaftan cut in the shape of a suit, a jaw-droppingly obese defence lawyer with a pudding-bowl haircut, heavy horn-rimmed spectacles, a booming voice and an astonishing, rollicking, mischievous, rapier wit—David Lange.

Lange was the last of twelve people seeking the Labour nomination for the safe seat. At the end of the long night, the chair of the meeting introduced him as the man who’d had the longest wait. ‘And I’ve got the biggest weight!’ he boomed. The hall erupted in cheers and laughter. Mike Moore, who was also seeking the nomination, whispered to his wife, Yvonne, ‘It’s all over, he’s got it …’

The man who would eventually defeat Muldoon became a Member of Parliament because of him. In true Shakespearian fashion, Muldoon’s dark deed set in motion events that would lead to his eventual downfall.

Two weeks after the Royal Tour had ended, Muldoon was scheduled to open National’s by-election campaign in Mangere. Ian Cross never visited Parliament, but quite by chance that very afternoon I ran into him strolling down a corridor with some cabinet ministers. On the spur of the moment, I said I really should cover the Prime Minister’s speech that night. Not ideally placed to refuse, Ian consented and two hours later I was on a flight to Auckland and a short cab ride from the Mangere hall.

All I remember from the meeting is that Muldoon was more bellicose than normal and when a young Samoan reporter, Fraser Folster, crept across the stage to adjust some recording gear, the muttering and hostility from the Pākehā audience was obvious. Even more painful to witness was Fraser’s acute discomfort and embarrassment at this reaction. At the close of the meeting I caught another cab, to St Mary’s Bay in Auckland, and spent the night with Helen. The next day I returned to Wellington and with a heedless regard for the consequences pulled the plug on my marriage and my Listener column—sending my life and the lives of others into free-fall.

HELEN AND HER THREE CHILDREN, Emily, Jacob and Ned, had been heading for England when I arrived in their lives. I dragged them down to Wellington to live in a tiny, squalid rented flat in Mount Victoria, but their trip to stay with Helen’s dad, Michael Forlong, a successful documentary film-maker now living in Surrey, couldn’t be delayed any longer. I decided to tag along.

Going overseas was still a big deal. Burton Silver and Peter Hayden organised a surprise farewell party. People assembled at Burton’s quaint Scorching Bay cottage and he led a convoy of cars on a magical mystery tour around the Miramar Peninsula to Shelly Bay, then still an air-force base whose gates normally closed at ten, but Burton persuaded them to leave them open. He herded everyone onto a jetty where a coastal trader was waiting, with more guests hiding under the hatches. Burton, who combines comic genius and lateral thinking with meticulous preparation, handed out souvenir boxes of matches emblazoned TOM SCOTT CRUISES. There was music, food and wine. It was a balmy, starry night. Out on the water we passed a Japanese fishing boat at anchor and Ian Fraser yelled out, ‘What about some squid pro quo?’ which we all thought was hugely jolly.

I was quite overcome that Burton and Peter had gone to such elaborate lengths on my behalf until I detected a mood swing and a swelling mutiny below decks. The more militant of the feminists in our midst had gathered to discuss the unforgivable misogyny of Burton not including Helen’s name on the matchboxes—it was thoughtless, insensitive, typical of our patriarchal society and bordered on a war crime. No, it was worse than a war crime!

I wanted to bring Shaun on the trip, but quite rightly Christine thought he’d been through enough upheaval, plus she didn’t want to disrupt his schooling. Not that the latter would have mattered—he was super bright in his own singular way. One dusk when a friend was loudly admiring a sinking sun, six-year-old Shaun coughed politely at her elbow and offered a gentle correction. ‘Actually, the sun is not sinking, Claire. It stays in one place. The earth is rotating, creating that impression.’

I DIDN’T ENJOY ENGLAND. PARTLY because I was missing Shaun terribly, and partly because it was bleak and freezing in the terrace house in Whitstable by the sea, it was bleak and freezing in the apartment block nestled amongst Oxford’s dreaming spires, and it was bleak and freezing in the Georgian manor house set amongst skeletal trees in flat Surrey countryside. The common denominator seemed to be clanking Califonts, damp sheets and burnt toast.

Phil Melchior was working for Reuters and over some boozy lunches he introduced me to his Fleet Street chums. Two newspapers were interested in hiring me. The pay was pitiful and I could be a writer or a cartoonist, but not both. I wanted to be both. I submitted samples of my work to Punch, the once legendary, now deceased weekly humour and satire magazine. I got a letter from the late, great Alan Coren, whose brilliant columns were the only enjoyable thing about sitting in a dentist’s waiting room, in which he offered me a job. I was elated—but not because I wanted to work there. I didn’t. I just wanted proof that I was good enough to do so. It meant I could go home. My homesickness was crippling.

But first there was a trip down the Grand Union canal, which I enjoyed despite the bitter cold. In the absence of roads, motor vehicles and other signs of civilisation we glided along languid waterways, down staircases of locks and through serene landscapes that seemingly hadn’t changed for centuries. Then it was off to the south of France in a swaying, groaning campervan to where Helen’s sister Debbie, her partner Roy and their two children were living in a stone fort atop the Île du Levant off the coast of the Riviera, near Toulon.

Before we left I went into Michael’s study to phone Shaun on his sixth birthday. There was no answer from Christine’s house. I rang around her friends, mindful that Maggie, Michael’s second wife, would be timing me on a stopwatch in the next room. I got uncomfortable, cagey answers from everyone I spoke to—Shaun was fine, they just weren’t sure of his precise whereabouts. I widened my search and finally got to speak to him. He was staying with neighbours. His quavering voice broke my heart. I told him I would be home soon and he was relieved. It turned out Christine had gone on another trip to China. I got off the phone and dissolved in tears recounting this to Helen. She said I didn’t really care about Shaun—I was crying for myself.

It was one of those cockpit-warning moments—‘Whoop! Whoop! Pull up! Pull up! Low terrain! Low terrain!’ There was nothing to be done. Helen was pregnant with Sam—one of the great joys of my life along with darling Rosie, the daughter Helen and I had next, and Will, Averil’s beautiful boy who feels like mine as well, and of course big, quirky Shaun, a constant source of astonishment and laughter. They have all grown into sensible, caring, considerate, creative, amusing adults, curious about the world around them and their obligations to it. I blame their mothers.

I went to France counting the days until I could return to Aotearoa. I don’t tan, and even if I did the nudist beaches on the Île du Levant were frequented by aging British homosexuals. As they were about to leave the surf they turned their backs to the sands and worked frantically on their genitals until they approached porn-star dimensions. I couldn’t compete with that, and if I tried it could easily have been misinterpreted. I didn’t want the embarrassment of being hit on by some perfectly decent gay bloke who through no fault of his own got the wrong idea—or worse still, being completely ignored by the loneliest homosexual on the beach, who averted his gaze and shuddered when I waddled past.

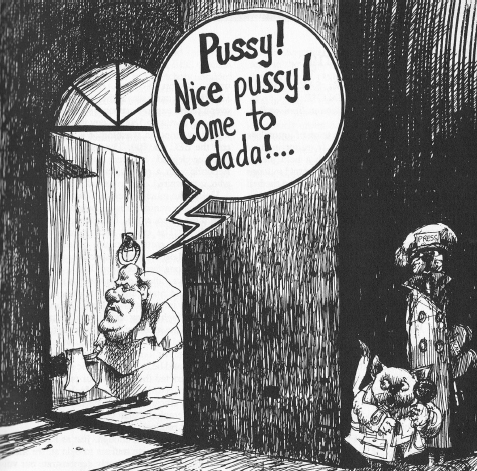

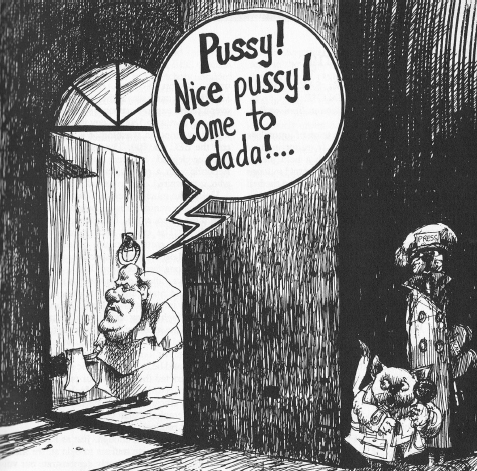

Instead I found a shady spot on the stony ramparts and wrote the first draft of my second book, Overseizure, a mock travel diary that I also illustrated with ink and pencil shading. Published by Whitcoulls, it sold very well and was reprinted several times to meet demand. A character not dissimilar to Michael Forlong featured prominently—and not always in a flattering light.

His first wife, Elizabeth, Helen and Debbie’s mum, an elegant and beautiful lady, came to stay on the island with us. Elizabeth could be a prickly flower and easy to offend but I grew very fond of her, and she of me. After dinner in the cool of the evening, when I regaled everyone with the work in progress, Elizabeth led the laughter—which gave me permission of sorts to continue.

WHEN WE RETURNED TO NEW ZEALAND we lived for a time with the brilliant, revolutionary, vastly entertaining architect Ian Athfield and his gorgeous, spirited wife Claire, a gifted interior designer in her own right, in their extraordinary cement block and white plaster Greek village of a home slipping and a-sliding, ducking and a-diving down a Khandallah hillside above the Hutt motorway and Wellington harbour. In the distinctive tower with its bulb and round windows for eyes, I finished the illustrations for Overseizure, and it was launched lower down the hill in the Khandallah Arms, a drab cube of a house to which Ian had added a double verandah and dazzlingly transformed it into a Wild-West saloon. Pooling our resources, Helen and I were able to afford a half-renovated house in Wadestown backing onto the town belt. There was a tennis court tucked up in the pines. Friends with children the same age as ours lived within easy walking distance. And I returned to the Listener.

When hiring me, the new editor, Tony Reid, made a point of telling me that circulation had gone up when I was away. I knew I was home. Ed Hillary told me that after climbing Everest in 1953, walking down London streets, cabbies and pedestrians would yell out, ‘Congratulations, Ed! You’ve done very well for your country!’ Back in New Zealand people would yell out, ‘Congratulations Ed. You’ve done very well for yourself.’

In my absence, Karen Jackman wrote a splendid column on politics for the Listener and I played no part in the coverage of the 1978 election—save for participating in a live television interview on election night while attending a Wadestown party.

The reporter was Simon Walker, who had recently been called a ‘smart alec’ in a testy studio exchange with Prime Minister Rob Muldoon. Simon’s crime was to call Muldoon ‘Prime Minister’ with such mock respect it was obvious he didn’t consider him worthy of the label. Simon went on to work for David Lange, British Prime Minister John Major and Buckingham Palace. When Her Majesty, unaccountably immune to the charms of the Sultans of Swing, decided to forego a Dire Straits concert at the Albert Hall she lent the royal box to Simon and whomever he wished to include. I was in town editing a documentary on Ed Hillary for Channel 4 in the UK and made the cut. At interval we exited a grand rear door and crossed a wide corridor into a chandeliered reception hall where liveried staff treated us as if Her Majesty were in attendance, gliding amongst overwhelmed guests with silver trays laden with champagne and canapés. Forget the mud and overflowing toilets of Woodstock and Glastonbury—this is how you attend a rock concert!

On election night 1978, despite Labour winning most of the popular vote, National won most of the seats. For a while early in the evening it looked like a close-run thing as Muldoon’s majority in the House was reduced from seventeen seats to nine. My live-to-air interview with Simon Walker, who looked about twelve, went as follows.

SIMON: Here’s a man who must be disappointed with the result.

ME: I was worried satirists would go out of business. It was touch and go there for a while. George Chapman was dousing himself and his wife with petrol outside the bunker, and Muldoon was rolling cyanide capsules around in his mouth, but they managed to hold on.

SIMON: So you’ll be back in business next year?

ME: I’ll be back in business next year.