AFTER NEPAL, JAPAN IS MY favourite destination. I can walk through Japanese cities like Kyoto, Sapporo and Nara and say to myself, ‘I could live here’—something I have never felt in Nepal, or few other places actually.

My fondness for Japan began when Averil’s son, Will, completed his degree in philosophy and languages and moved to Tokyo. He wants eventually to join the UN and work on their refugee resettlement programmes. Smart boy. When global warming and sea rise submerge the coastal plains where most of the world’s populations live he will never be out of a job.

One trip we stayed at the Hilton Tokyo in Shinjuku-ku. The views after sunset from the New York Bar on the fifty-fifth floor were wondrous. A gaudy neon Milky Way marched off into infinity in every direction.

One evening I was sipping a cocktail, flicking idly through the International Herald Tribune, when I read that 400 Japanese company employees on a junket to the southern Chinese city of Zhunhai had a three-day orgy with 500 Chinese prostitutes. These people have so much to teach the west.

I looked dreamily out the window. The last rays of the setting sun were hitting the snow-covered upper slopes of Mount Fuji and I suddenly felt ill. We were climbing it in a few days. Averil and Will were excited. I was experiencing a deep dread. Jesus Christ, it was the same bloody height as the hill up to Namche Bazaar; I’d struggled up that the last time and I was in my fifties then.

It proved to be as hard as I feared. My feet were leaden. Every step was an effort. Going up some steep sections, Will grabbed my belt and heaved me up just as Mingma had done for the Burra Sahib. I spared what little breath I could to thank him. Ever polite, he replied, ‘No problem. We could rest here a bit. I could do with a break myself.’ He was lying.

We reached the last lodge well after dark. They put me on oxygen but the cylinder was empty. I had seen this movie before.

We slept in communal bunks like submarine crews. At 3 a.m. alarms sound for the assault on the last 300 feet to the summit—the intention being to get there before sunrise and the start of a brand-new day. I stayed in my sleeping bag as Averil and Will scrambled up in the freezing cold and black. They made it as the sun slipped above the distant horizon. To the delight of the locals, Will stripped to his waist and did a spirited haka.

I stripped to my waist for my GP when I returned home. He needed a few moments to get the better of his gag reflex then attached a stethoscope to my ribcage. The negative buoyancy invaluable when you are stepping into rotating lawn-mower blades made it difficult to spot, but I definitely had a heart murmur.

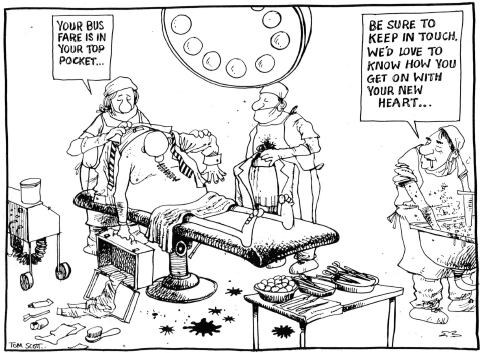

Ken Greer dispatched me to the Heart Centre at Wakefield Hospital, where Malcolm Abernethy and his team conducted an echocardiogram—they bombard your chest cavity with ultrasound waves and scan the results. I had a thickened left ventricle wall, indicating my heart was working harder than it should. This was followed by an angiocardiogram, where they injected radio-opaque dye into a vein in my right wrist and monitored its transition through my heart on a large X-ray screen. I am not a cardiologist, but when seasoned professionals start screaming ‘FUUUUCK!’, pull out rosary beads or run from the room in tears, you prick up your ears. I’m exaggerating—no one pulled out rosary beads—but Malcolm did suggest very gently that I should go home and fetch my pyjamas and toothbrush, and not run any half marathons on the way.

OPEN-HEART SURGERY IS NOT SOMETHING you take out full-page ads in newspapers to announce. I kept it quiet, but people found out. I got a lovely text message from All Black coach Steve Hansen wishing me a speedy recovery, and a very amusing one from the then Prime Minister, John Key, wishing me well and saying that it was highly unlikely he would ever need heart surgery because according to Nicky Hager’s book Dirty Politics he didn’t have one.

I got two emails from John Clarke that made me laugh out loud at the time and fill me with sadness now. They are all the more poignant knowing that he died almost instantly while walking in a pristine wilderness from catastrophic heart failure.

Dear Tom,

I understand you’ve recently undertaken some renovations in the central thorax area and I hear that they’ve gone well. Excellent. I would expect nothing less and I’m delighted to hear it. The triathlon season begins in a couple of months and I’ve put you down for a start in the event at Warkworth in mid-December. You’ll be off scratch in the 20–27 age group. Just use the swim leg to limber up a bit, sit somewhere near the front of the peloton during the bike section and mow them down in the run. We salute you and hope all continues to go well.

All best from all here,

John

And this one on my birthday two months later.

Dear Tom,

I am informed by Ginette that the odometer is clicking again today. You are to be congratulated and I understand from the makers of plumbing equipment that you are under warranty until 2046. The position will be reviewed every fortnight after that so please get everything important done in the intervening period.

Happy birthday.

Yrs,

J Clarke, Manawatu

On the Sunday evening before the Monday-morning operation, Averil and I met in turn with the cardiologist, the surgeon, the anaesthetist, and the perfusionist—the latter’s job was keeping a weather eye on the fancy machine that would be doing the work of my heart and lungs while they were temporarily decommissioned. There was lots of talk and discussion about risks. I asked the perfusionist about power outages. There were back-up generators and if they failed they had batteries.

Averil was anxious and tearful. I felt strangely calm and relaxed. Like Woody Allen, I wasn’t frightened of dying—I just didn’t want to be there when it happened.

I had been truly blessed by Averil entering my life. Blessed with all my children, including Will, who has none of my chromosomes and is the richer for it. Sam and Jessica had gifted us with one grandchild. I had hoped to be around when Shaun, Rosie and Will had theirs. C’est la vie. I fell asleep knowing that I was a fortunate man who had led a fortunate life. If I woke up after surgery, everything from that point on would be a bonus.

I CAME ROUND IN A strange, grey light in a recovery room. Everything was fuzzy and in soft focus. I didn’t know where I was. I knew I had been subjected to open-heart surgery but what was the outcome? Had I woken up, or was this a poorly lit dream? Or, worse, was I on the other side? Whatever that was.

A familiar silhouette with a corona of light around blonde hair leaned close. I couldn’t make out the face. A gentle voice spoke and someone squeezed my hand—my darling Averil. Unless by some extraordinary and tragic coincidence Averil had died as well, it meant I was alive.

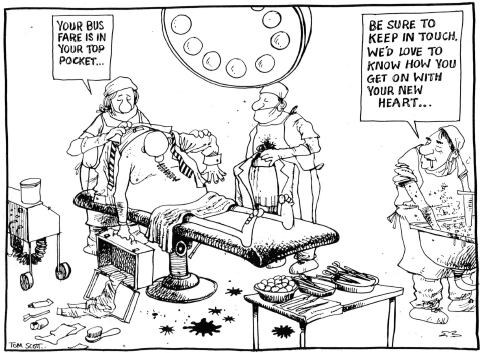

She told me that it had all gone smoothly and that everyone was pleased. I had sutures in a wound stretching from my groin to my right knee where they had borrowed a vein to replace some occluded coronary arteries. I wore pressure stockings on both legs. An aortic valve from a bullock replaced my own (Model No. TF-25A, which I thoroughly recommend), which had been steadily turning into chalk as it struggled to close properly. My sternum was stapled together. Subcutaneous connective tissue and skin also divided by the Skilsaw was glued back together. I had drainage tubes leaving my lower ribcage. I had tiny electrical jumper-leads entering my upper ribcage and running to my heart in case my blood pressure flatlined and my pump needed starting again. I was connected to a blood-pressure cuff. I wore a pulse oximeter on one finger. I had a saline drip feeding electrolytes through a catheter into one vein. I had a morphine drip feeding soothing opiate into another. I had light, clear plastic tubes delivering oxygen to my nostrils.

I was alive, and the good people at Wakefield Hospital were doing everything humanly possible to keep me that way. I would get to see my mokopuna grow up (Freddy and Gus have since made stellar entrances, and another grandson is biding his time in the green room of his mother’s womb). I would grow old with Averil. Unlike my brother Michael, I had been given a second chance.

I know she is not the slightest bit interested but I would use it to take Averil to Lake Bled in Slovenia and Dubrovnik in Croatia. We both want to visit Venice and Barcelona. We both want to live and work in Paris and New York. There is so much to do and see!

Waves of euphoria and gratitude swept over me. The taste of butterscotch filled my mouth.

Then I noticed some other bastard recuperating from surgery, doubtless nowhere near as serious as mine, had the bed next to the window with a view, and I instantly felt short-changed.

I’LL LET THIS FRAGMENT FROM Higher Ground have the final word.

EXT. SUMMIT EVEREST—MOMENTS LATER

WIDE SHOT: We circle the New Zealander and the Sherpa hugging on the roof of the world. Rotating slowly below them is the brown plateau of Tibet and the icy peaks of Nepal. Around them nothing but sky. Above them the Indian ink of space.

Super the Title: Everest Summit—11 a.m., May 29, 1953

TENZING holds his flag-bedecked ice-axe aloft while HILLARY takes a picture—

TIGHT ON: The famous Summit photo—

HILLARY takes photographs north, east, south and west—

TENZING scoops out a depression in the snow and places offerings of sweets, the pencil, the karta, Lambert’s red scarf and the flags from his ice-axe.

TENZING kneels and prays quietly—

TENZING: Thuji chey, Chomolungma. Thuji chey, Chomolungma.

Super the translation: I am grateful, mother goddess of the world. I am grateful, mother goddess of the world.

Observing TENZING’S tribute, HILLARY suddenly remembers something, and reaches into his shirt pocket for the small crucifix a tearful John Hunt gave him three days earlier on the South Col and places it alongside Tenzing’s tributes to the gods.

He quickly scans the horizon, then checks his watch—

HILLARY: Right. We’re out of here!