part two

Occasionally, a small group of people glides through an empty parking lot as I make my way out of town. We avoid each other.

I move quietly, on full alert.

It seems I have chosen a good night to leave. The moon is waxing full and makes it easier to see in the dark despite a thin cloud cover.

Those of us defying the curfew are so vulnerable. This part of Route 5 is just one long strip of commercial development, one parking lot after another. It’s astounding that not a single car comes past.

Caution slows me. I am as wary as a cat. I imagine threats behind me and frequently spin to catch a would-be assailant only to find an empty road at my back.

* * *

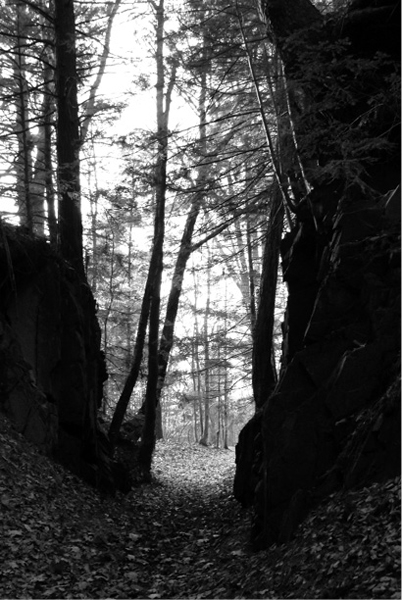

The shops eventually give way to woods. The moon has gone behind a dense mat of clouds. It’s impossible to have anything but a dim sense of where to put my feet. But I feel safer than I did walking through the parking lots. And each step north takes me farther from the law knocking at my door.

The night is long, punctuated by the occasional barking of dogs. But no one opens a door to look out. It is almost as if they’re afraid to check what has startled their pets.

I remember a few years ago hearing about a pack of dogs that hunted at night just for the pleasure of the kill. They weren’t hungry. They were well-cared-for pets. But they’d gotten a taste for blood, for the chase, slaughtering small livestock within an ever-broadening circle of their homes. People were afraid the pack would turn on children next.

I wonder if abandoned dogs are forming packs now, preying on solitary walkers.

Inside my head a voice whispers, Don’t think those things. Think about getting to Canada. Think about finding Mom and Dad. Don’t think about anything else.

* * *

At last, after hours of walking, I reach the village of Putney. The town is densely settled. I carefully thread my way through and continue north a little longer before crawling inside a shed and sitting out the remainder of the night.

Through this evening’s entire march I saw no cars at all and only one small convoy of military vehicles. And it was easy to hide from them.

Holding Jethro’s bear, I huddle in the abandoned shed and imagine my parents just up ahead, encouraging me.

Knowing their preference for small roads, I think they, too, could easily be walking Route 5. They certainly drive it often enough. My mother’s taken hundreds of pictures along this road.

The idea quickens my heart. The idea that I might find them.

* * *

With a couple hours of sleep to go on I resume my daytime schedule. I feel safest walking in daylight. I don’t worry about packs of dogs. I worry about a thousand other things … what I’ll eat, where I can wash up and relieve myself, whether I’ll find a safe place to stop for the night, whether someone will get too curious about me, whether I’ll make it all the way to Canada before I’m arrested, whether someone will hurt me, or kill me, whether I’ll be hit by a car, whether I’ll find my parents along the way … but I don’t worry about packs of dogs.

I’m comforted by the number of people walking the road with me. Some heading north, some south. Though we avoid making eye contact, I feel less conspicuous with so many other walkers.

They’re obviously not all heading to Canada. I don’t know where they’re going. I’m not about to ask.

Daytime traffic is pretty light compared with what it used to be. I guess because fuel has been so scarce. Nearly every service station I pass has a sign saying “No Gas.” That may explain why my parents left on foot. It may also explain why there are so many others walking.

On this part of Route 5 the road is treacherous, twisting around corners with no shoulder to speak of, sharp, dented guardrails, and rock walls hovering over the road. I travel as deep into the shoulder as I can get, but there are times when there’s no place to be safe.

Occasionally I get squeezed between a guardrail and a speeding car. Some drivers do their best to avoid me by drifting into the opposite lane, but some get a thrill out of terrifying me, coming as close as possible without hitting me.

Trucks are the worst, though. When they pass I’m slammed by a wall of wind that at best stings my skin but sometimes lifts me right off my feet.

Fortunately there are even fewer trucks on Route 5 than cars. And fewer cars than slow-moving military vehicles. And they don’t seem to be interested in stopping along Route 5. At least so far.

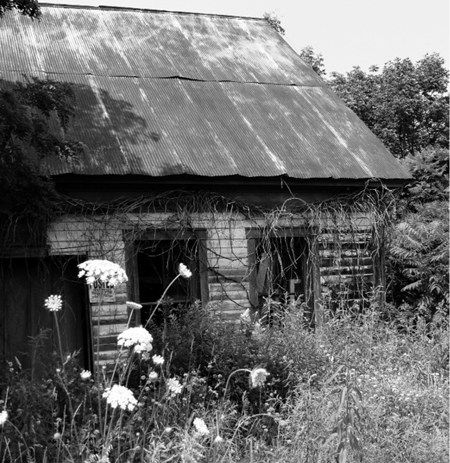

I’m tired from walking through most of the night last night, through most of the day today. I’m ready to stop long before curfew but my search for collapsing barns, abandoned houses, unlocked sheds to slip inside for the night proves unsuccessful. I push myself to keep going. My burning eyes sweep over both sides of the road, desperate for a place to stop. And, at last, a sagging barn offers itself.

The night, though cool, is sweetly scented with blossom. I curl up inside my parents’ old camping blanket and try to sleep. I’m dead tired. My legs ache, my mind is mostly a dull buzz. But there is this hot wire of alertness that never goes out and keeps me from sleeping truly deeply.

Another day, another section of road that curves and rolls unceasingly up, down, and around narrow shoulders where it is almost impossible to get out of the way of traffic. Fortunately, there’s less and less traffic all the time, particularly on the long stretches of road between towns.

Trying to make my cash last, I’ve become expert at picking food out of Dumpsters … bar trash is the best. It turns out deep-fried potato skins covered in melted cheese is my favorite. I never used to like that stuff … too greasy. Now I fantasize about it.

A lot of restaurants seem to have closed, but the bars appear to be doing fine. Most of them use generators. I can hear the growl of the motor long before I reach it.

Trash pickup isn’t regular either. Garbage cans overflow, Dumpsters are filled to the brim. It’s easy pickings. I just wish there were a few more of them.

I walk through Westminster, Bellows Falls, Springfield. I walk through woodland and farmland.

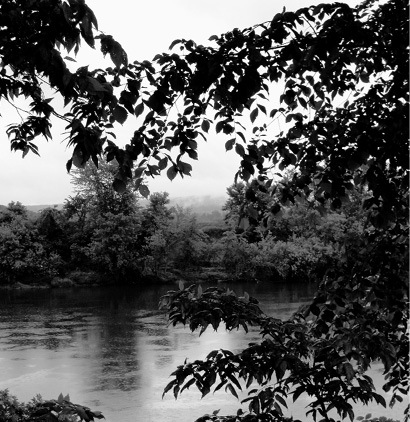

For long stretches I’m within view of the Connecticut River.

I follow trails into the woods from time to time where I can rest and eat, relieve myself, study the map. I still have so far to go. But I’m chuffed at how far I’ve come already.

Washing up in a gas station bathroom, I wish I had someone to walk with. Someone to talk with.

I miss the children at Paradis des Enfants more than I can say. Not even Jethro’s bear comforts me. At least not enough.

I miss Chloe and the hours we spent cruising the neighborhoods with our hips swaying, sassing anyone who passed us. My hips aren’t swaying now.

Small cuts, bruises, and bites lick their little tongues of fire all over me. Some jerk throws a soda can at my head out his open car window. I pick up the can after it hits me and cash it in for the deposit at a market in Ascutney.

As curfew approaches I take shelter behind an abandoned building. There is no roof over me tonight, but it’s not raining and the bugs aren’t bad.

My legs scream with pain after another long day’s march.

I groan silently, easing myself down, trying to get comfortable.

Until I turned thirteen, I hiked with my parents every Sunday morning. I loved those hikes. I can admit it now.

I miss walking with my father, stopping to examine a plant, learning its Latin name. I miss my mother, obsessively recording with her camera the fall of light through leaves, the growth of fungi on trees, a rock cairn left by hikers who came before.

If only I knew which way my parents had gone. It’s possible they were arrested and are sitting in some jail now. But I choose to believe, instead, that they, too, are making their way to Canada.

They would advise, “Radley, keep yourself safe. We’ll find you when this nightmare is over.”

I’m hopeful I’ll find them before that.

I must not allow even a moment’s lapse in attention. Not a moment. Less than an hour ago the police caught someone who was heading toward the woods where I had only just hidden. The siren screamed, the revolving light making terrifying shadows in the trees and across the sky.

I’d only been in here a few minutes. Only just wrapped myself in my parents’ camp blanket. If I’d tried to squeeze in one more mile, tried to find a place that felt safer, a barn, a shed, if I hadn’t given up exactly when I did and settled for sleeping under the trees, the police would have caught me.

If the traveler had not been caught, he would have spent the night in these woods so close to me I don’t know how I could have avoided him. With so many of us on the road, why hasn’t this happened before, why hasn’t someone else ducked into the same place I’m hiding for the night?

Or maybe it has happened. Maybe I have spent the night in a barn where someone else lay hidden, someone who felt safer remaining concealed from me.

I pull my knees up under my chin and don’t realize I’m crying until I wipe away the tickling on my cheek and my hand comes away wet.

Today the walking is miserable, in heavy rain.

My mom loves rain walking. She’d come back from hours of following wet paths, her hair and coat dripping.

She’d stand in the front hall making puddles on the floor.

I wrinkled my nose at the scent she carried up the stairs with her on those days. That wet wool smell.

How I took for granted being warm and dry.

Mom would come into my room, having stripped out of her wet things, her robe belted around her waist, and she’d sit on the side of my bed with her animal eyes and her damp hair smelling like dog fur.

I loathe walking in the rain.

I’m chilled and drenched and wretched.

When I find an empty house somewhere south of Windsor with a For Sale sign in front, I consider my options. The house has a deep, concealing porch. The grass on the lawn is up past my knees. If I climb onto that porch I’ll be invisible from the road.

If a realtor comes to show someone the place … I can get away … I make a quick plan of how to escape if a car pulls into the driveway. And then I’m up on the porch and hunkering down before I can change my mind.

I spend the day under the shelter of that porch roof. This is the first day I’ve allowed myself to stop. I’m torn, thinking I can catch up with my parents if I just keep going. But today the need to find my parents is not as strong as my need for shelter.

Maybe my parents are doing the same. Mom likes walking in the rain, but Dad hates it as much as I do. Maybe they are just up ahead, sitting knee to knee in an abandoned horse stall, congratulating each other again on how smart they were to send me to Haiti when they did.

Another day of drenching rain.

After spending the night on the porch, I’m tempted to stay but I’m afraid of stopping any place for too long.

I climb down off the porch and walk through Windsor, instantly regretting my decision to keep moving. Rain slides its chill fingers through my hair, down my collar. I am so cold, so wet.

My hair hangs dripping over my face. I must look like something the cat dragged in. I definitely feel like something the cat dragged in.

After raiding a moderately satisfying Dumpster (no potato skins, no French fries, but an end of salami and some burnt chili in a soggy cardboard tub), I look again for a place of refuge.

Settling inside an empty barn, I remember one time, several years ago, my mother brought a package in from the front porch and carried it up the stairs to my bedroom.

“For you,” she said. “From Grammy.”

My mother’s mother had stunning taste. But she had no idea who I was or what I liked. Her gift to me was a cowgirl dress, a jaundice-yellow fabric printed with brown horses. It was the ugliest dress I’d ever seen. I couldn’t bring myself to put it on. I couldn’t imagine wearing it, even as a joke.

I feel a deep pain, like a punch to the gut.

I’d wear it now, if only I could have my parents, my grandparents, my old life back.

I’d wear it now.

Did I do the right thing leaving home? I’m so tired. I don’t know how I can keep going. The weather feels more like March than June. My skin is wet rubber.

The route twists and turns, heading south when I want to go north, east when I need to go west. I know I’m making progress. But I still have so far to go. And my map is coming to pieces in this sodden weather.

If I surrendered quietly, at least I would have shelter and food. And I could dry out.

Occasionally I find a dripping newspaper in a trash bin. Most of it falls apart as I try to turn the pages but there are articles about snipers picking off soldiers. Farmers protecting their property with hunting rifles. Prisons overflowing with looters and protestors. Under this emergency law, anything can get you arrested.

I feel cut loose from the world.

I wonder if the world actually still exists.

I’m floating in some alien universe without an air supply.

And I’m drowning in all this rain.

The sun finally breaks through late in the afternoon. I unfold my damp, gray, stiff, miserable body and begin to walk again.

I think about the children of Haiti, how they welcomed me, arms open, pushing their small bodies up against mine for the sweetness of human contact. I understand now. I understand hunger for the touch of another. I step off the road into the woods, look at the shredded map for the hundredth time, and lift up my face as the rain of the last few days evaporates from my hair, my boots, my skin; threads of steam rise off my clothes toward the warming sun.

I think of the children at Paradis des Enfants and hope they have not had so much rain.

White River Junction crawls with soldiers.

I’m terrified they’ll notice me. I try in every way to avoid calling attention to myself.

They have nothing to fear from me. They never did. I don’t want to topple a government.

I only want to be dry and safe, I only want something hot to eat.

I only want to find my parents and get my old life back.

My head itches, my hair stinks. I don’t bother letting it out of its clip. It’s too disgusting. Why didn’t I cut it before I left? I’d do it now if I had a pair of scissors bigger than the snips in my first aid kit. Of course if I chopped all my hair off I’d be more conspicuous. But it feels as if my scalp is crawling with vermin.

Once, when I visited my cousin in Montreal, I spent a small fortune to have my hair cut. My cousin had been teasing me about being a country mouse. In that beautiful city, in my flannel shirt and jeans, I felt like a country mouse. And so my cousin took me to her hair salon and I didn’t ask the cost.

My father paled when he got the bill. But he swallowed hard and told me my hair looked beautiful. All he said was he hoped my haircut would keep its shape for a very long time.

Once again I’m going to Canada dressed like a clod. And once again I’m in need of a haircut. I’d head for Montreal straightaway if my cousin was still there. But she lives in Miami now. At least she lived in Miami before all of this began.

I’m careful. Kids congregate in out-of-the-way places … the sort of places I seek for shelter. They look restless, angry, short fused. Usually they cluster in groups of threes and fives. The looks they give me are dangerous. I could never stand alone against them. It is safer to back away, not test them, even if they are close to my age. I can tell where I’m not wanted. Where I’m not safe.

So I’m surprised when not everyone looks at me with suspicion. A small boy waves to me as I pass. A little girl wearing butterfly wings and clinging to her mother’s hand turns and smiles at me over her shoulder. These fleeting moments of kindness give me hope that the world is not completely lost. I replay them in my head as I walk, as I settle down for the night. Like Jethro’s bear, they comfort and console me.

Several times I have seen bikes and considered stealing one. But stealing a bike is not like stealing those quarters from the people at the Manchester airport.

What a difference a bike would make. How many more miles I could cover in a day. How much more normal I would appear, pedaling a bike along the empty stretches of Route 5.

But I can’t steal someone’s bike.

And besides, I never learned to ride one.

There is a girl I’ve caught sight of several times. I’m curious about her.

How much I miss human contact. My mother was always hugging me, kissing my cheeks, brushing my hair off my forehead. It used to drive me crazy. I’d snap at her, try to hurt her, to keep her at a distance. Why did I do that? Why?

I fear this girl. She looks defiant, something in the way she holds her bony shoulders as she walks, something fierce in the glimpses I get of her pale face. And she travels with a dog. Just the sort of dog that has always frightened me. When I was little, the same sort of dog jumped on me, knocked me over. It terrified me. I don’t want to get too close to either of them.

I follow behind, silently, keeping a healthy distance.

But as wary as I am of the two of them, I also feel strangely drawn to them. The girl doesn’t look like the children at the orphanage, but there is something about her.

I creep along rather than stretching my legs at full stride. The girl moves slowly, as if something hurts inside her.

We stop for rest, food, water at matched intervals. The synchronization of wayfarers.

If the girl gets ahead it’s easy to catch up to her.

I worry about this attachment I’m forming. My mind wanders, spinning fantasies about her. It’s pure relief to think of something other than myself for a change. But it’s dangerous to let myself become so distracted. I realize a police car has driven past me several times in the last hour. I pray he’s not looking for me and take the first opportunity to duck into a gas station, get myself off the road, try to make myself look a little less travel worn.

And then, a mile or so later, I’m nearly creamed by the same cop as he comes careening around a blind corner, siren screaming. His car comes close enough, it brushes my sleeve.

Almost being hit steals my breath away. Makes my heart thunder. But there is also relief. He is after someone else.

The girl and her dog stepped off the road and into the woods moments before the policeman skimmed past me. They did not emerge from the trees after the tail lights disappeared.

Fine. I take the lead. Force myself not to look into the woods when I pass the place where she vanished. I just keep walking.

The weather turns foul again this morning. I find another empty house, another protected porch. With some food and water in my pack, I decide to wait out the rain.

I think maybe I’ve been dozing. Suddenly, a dog stands over me.

The fuzziness of sleep instantly vanishes. Replaced by the sharp focus of fear.

Pressing my back against the porch wall, I try inching away but the dog keeps closing the distance between us.

I jerk myself to a standing position, surprised when the dog shows no sign of aggression at my sudden move.

Instead, the dog lowers itself to its belly and inches close enough I can feel a trace of heat coming off it. Then it raises its nose and touches the hem of my pants. So gently.

It rolls onto its back and whines.

Even I can see the dog is submitting to me. But it is the girl’s dog. At least it looks exactly like the girl’s dog, the girl I’d been following.

The dog rolls back over, rises slowly, bows to me. It whines. Climbs off the porch, looks back at me, waits for me to follow.

I don’t know why I decide to go with it. Except, that girl. There is something about that girl.

Checking first to make certain no one is watching, with my blanket still wrapped around my shoulders, I grab my pack and step down from the protection of the porch, into the torrential rain.

The dog trots a few steps ahead, then turns to note my progress.

I had almost dried out on the porch. Now I’m instantly soaked again. I consider going back, but I don’t think I have that option anymore.

I think the dog is determined to retrieve me.

I’m led behind an abandoned silo where the girl is nearly hidden in the undergrowth. She’s deathly pale except for a blaze of red on each cheek. I touch her forehead. Fever ravages her.

Speaking gently, I cover the girl with my blanket, though it is already soaked and offers her no protection from the rain. I lift her head slightly and put my thermos of water to her lips. Her eyes flutter open, register my presence, then close again.

I have the money I collected from my parents’ drawers. I’ve been saving it. But I don’t hesitate to spend it now. Just as I used my money in Haiti to feed the children when they told me their stomachs hurt, now I must use what I have to save this girl’s life.

“My name is Radley,” I tell her. “Your dog brought me here. I think you need food. And water. I’m going to get something to help you feel better. I’ll be right back.” I don’t know how much she’s heard but she nods and groans. The dog lies down beside her, its head on its paws.

I remember passing a market in Norwich. I walk back to it, buy some Gatorade. I stop in at a little café and ask for some plain cooked rice, waiting while they fix it for me. When I ask how much I owe, the owner waves me away, tells me to feel better. I head back to the girl, almost expecting her to have vanished but she’s still there, shivering under my sodden blanket.

I give her sips of the Gatorade.

With each ounce of fluid, she claws her way out from the pit.

We are exposed in a way that makes me nervous. We have only the leaves overhead as protection from the rain. But I don’t dare move her.

The dog never leaves us for more than a few minutes and I realize I feel safe and useful in a way I have not felt since Haiti.

Within twenty-four hours the girl seems much better. “My name’s Celia,” she croaks. “My dog is Jerry Lee.”

“You heading north?” I ask.

Celia shrugs and says nothing more.

When she’s well enough to travel again we begin walking together. Celia makes it clear she doesn’t want to talk.

I think she’s too depleted, too exhausted to do anything but put one foot in front of the other.

I try to hold my tongue but there are so many questions I want to ask.

As it is, we don’t cover much ground our first day walking together.

After we’ve settled down in the woods for the night, I try again to question her. Rudely, she turns her back to me and goes to sleep.

I yearn to hear the sound of my own voice, to hear the sound of hers. I’ve been alone for so long. After the intimacy of the children at the orphanage, I ache for someone beside me.

At the end of our second day of silence Celia tersely thanks me for nursing her back to health.

I use the small opening she’s given me to ask where she started her journey.

But she doesn’t respond.

What if she decides to flag down a cop? What if she turns me over to one of the convoys of soldiers passing on the road? I don’t know anything about her.

But I hate the idea of being alone again. I decide to keep trying with her, at least a little longer.

“Are you still in school?” I ask.

She glares at me for a moment. Doesn’t answer.

I decide to ignore her rudeness. I imagine, instead, an orphan at my side, holding my hand, singing in a high, sweet voice.

It doesn’t help.

Celia prefers to sleep in the woods. I prefer sheds and barns.

Grudgingly, after a brief exchange, she agrees to decide at the end of each day whether we can slip, undetected, into some sort of shelter or whether we are better off under the trees.

When no shelter presents itself at the close of day, we have little choice but to stay in the woods. Jerry Lee is the most agreeable of the three of us. He sleeps wherever Celia sleeps, no protests, no questions asked.

One evening, behind a condemned house, in a sagging barn hidden from the road, Celia gazes out at the rain slamming down through the darkness and admits the night’s accommodation, under a roof, leaky as it is, has some advantage. Water runs down the walls and collects in puddles, but we are able to find a dry stall to share with the mice and the mosquitoes and the ghosts of horses past.

Once we’re beyond Lyndon, areas of settlement thin out even more. We are about two-thirds of the way now. I’ve spent most of my money on food … Celia is much fussier about Dumpster diving, though once I get her started, she can’t resist raiding the trash bins behind Dunkin’ Donuts.

The power supply is so erratic. One night we’ll see lights in farmhouses as evening approaches but the next evening everything is dark again. Gas must still be scarce, too, judging by the lack of cars on the road. There are fewer walkers this far north. But enough that we don’t stand out.

Following a brief discussion, we agree to spend the night in an old barn in an overgrown field. The sun has been down for a couple of hours when we hear the sound of feet approaching. Jerry Lee is up instantly, making a noise in his throat I’ve never heard before.

Outside, it sounds like a mob on the move. The ground shakes with their approach.

I think, now we are going to die. Why didn’t I listen to Celia about not sheltering in barns?

Jerry Lee seems to be considering our options. He puts his nose under Celia’s hand, and indicates his intention to leave. Silently we gather our things, silently we begin to move toward the back of the barn. Making his way in the dark, Jerry Lee guides us through a low door. We crawl out into an overgrown yard while a mass of boys push on the side of the barn, intent on collapsing it. Slithering across the weedy expanse, we slowly make our way to the woods beyond.

The weary barn groans in protest as the boys continue pushing on it. They grow louder with their effort and their excitement.

I tremble with fear in our hiding place inside a thicket of trees. Jerry Lee leans against me, comfortingly.

As part of the barn tilts impossibly, sighs, and collapses, headlights come down the road, shining on the young mob. The boys scatter.

One runs into the woods not far from where we are hiding. He passes so close we can hear his breath.

He exits again at a distance, never seeing us.

The rest of the barn lets go on its own and the dust makes us sneeze, though we make no sound. Our eyes burn and tear.

The police search through the rubble for hours, and then, satisfied there’s no more to be done, they leave.

Their headlights disappear around the bend. The sound of their tires trails off into the distance.

Celia whispers, “About a month ago kids started setting fire to barns, but one of the fires spread and took out two cornfields and a house. Now the little thugs just push stuff over. They’re trying to scare anyone hiding inside.”

“It worked,” I say. “I thought we were going to die. I’m sorry, Celia. I didn’t know about any of this.”

“It’s not your fault,” Celia says, thawing a bit. “I should have told you why I didn’t want to spend the night in a barn.”

I kneel in the underbrush and wrap my arms around Jerry Lee. “Thank you,” I whisper into his fur. He suffers my embrace.

When I let him go, he moves away, sits beside Celia, gazing into what’s left of the night.

We say no more about it. But from then on, Celia decides where we stop to sleep.

Route 5 has pulled away from the Connecticut River and I miss it. The river had been my steady companion for so many miles of this journey. It provided a place of rest and welcome.

Now acres of farmland alternate with miles and miles of woods.

Having Jerry Lee along makes us look almost normal, like a couple of girls out walking the dog.

I travel the slow swing of Jerry Lee’s and Celia’s gait, my eyes always scanning the horizon for my parents. If only Jerry Lee could find them somewhere along this road …

But how many miracles is one dog allowed?

Celia begins to relax with me. When a girl comes tearing past in a red convertible, Celia looks at me and says, “Sweet.”

I tell Celia, “My friend Chloe had a convertible. Well, it was her father’s really. A Corvette. It was his pride and joy. He didn’t let anyone touch it. But once Chloe picked me up in it and we cruised down to Massachusetts and back. Her father tried to punish her when she brought the ’Vette home, but it was hard to punish Chloe.”

Celia doesn’t make a comment, but she doesn’t turn away either.

Having Celia turn to me and say “sweet,” it’s like she’s given me a gift.

Telling her about Chloe, I am giving her one, too, whether she knows it or not.

Celia grumbles about the endless miles, but for me they begin to fall away.

I’ve hit some sort of stride. My body no longer minds the endless foot pounding, the discomfort of nights spent on hard ground or inside abandoned barns. I no longer expect every car to hit me, I no longer expect every cop to arrest me. Having Celia and Jerry Lee at my side gives me something to think about.

In Barton a man pulls up alongside us. He smiles at us through his open car window. He’s got a nice face. A warm smile. He warns us to be careful, that there are people around looking to hurt us. He says if we want we can spend the night at his place; that tomorrow he’ll give us a ride wherever we need to go. Meanwhile we can have a hot shower, eat some real food, sleep in a soft bed.

It’s the first time anyone has approached this way in all the weeks I’ve been walking. I never thought there might be safe houses, but that’s what he’s offering. I wonder whether Celia and Jerry Lee and I look so obviously out of place here, or whether this guy is particularly perceptive.

I tell him thanks and start to move toward his car when Celia grabs my hand and stops me. Her eyes flit over to Jerry Lee.

His hackles are up.

Celia, squeezing my hand, tells the man our aunt is waiting for us, that we’re staying with her for the summer, that we have to get back soon or we’ll be in big trouble.

It’s the most I’ve heard Celia say since we started walking together.

“I could drive you there,” he offers. “To your aunt’s…”

I don’t understand why Celia and Jerry Lee have taken against him. He’s so accommodating. And what he offers is so tempting. Surely he’s someone we could trust. Wouldn’t I sense it if he weren’t?

But I decide to remain with Celia and Jerry Lee anyway.

“Sorry,” I apologize to the guy, genuinely embarrassed. “But thanks anyway.”

Suddenly the guy transforms. His expression turns ugly. He spits at us.

“Stupid bitches,” he snarls. Then he peels away.

I stare after him, totally shocked. “What a jerk! What a freakin’ jerk! How did you know?” I asked. “How did Jerry Lee know?”

“It’s a skill we’ve developed,” Celia says.

“Thanks,” I say. “I would have gone with him.”

She nods. “Good thing you didn’t. Guess we’re even now.”

“Even?” I ask.

“You saved my life. I’ve just saved yours.”

We are close to the border. I worry about that creep coming back for us. I worry about crossing into Canada. So we switch our waking and sleeping, waiting for full darkness before starting out.

Used to be I fretted most about the curves in the road and someone coming around the corner too fast and hitting me. Now the scariest sections are the ones where we can see for a distance in every direction. If we can see that far, everyone can see us, too.

But up here, as we approach the Canadian border, there’s almost no traffic and very few walkers.

Each night the natural light has lingered a little longer, the darkness closing in a bit later. I’m not sure of the exact date though I wonder if we’re near the solstice. That would make sense.

When I left Brattleboro, I walked out of town under a waxing moon. Tonight the dark is nearly impenetrable.

Celia and I walk haltingly, each of us with a hand in contact with Jerry Lee, moving blindly, closer and closer to the Canadian border. When a car approaches we drop down. There’s almost always a place to get off the road.

But there are almost never any cars.

“I wonder how long the power will be out this time,” I whisper.

Celia shrugs. “It’s been like this for a long time now. On one night, off three. Hackers, probably.”

“There’ve got to be people clever enough to counter the hackers,” I say.

Celia laughs quietly. “Sure there are. But they were some of the first to be picked up and hauled off to jail.”

Finally we make it to Newport.

After all of this walking at last we’ve reached the border. We move silently through the sleeping town.

“Tonight we cross,” I whisper.

Celia nods. I feel it more than see it.

“I never asked if you had a passport,” I say.

Celia is silent for a few moments. “Do I look like I have a passport?” she answers.

I shake my head no, which, of course, she can’t see.

“You do, don’t you?” Celia says.

“Yes,” I say. “Yes, I have a passport.”

“Why the hell don’t you just go through a legal crossing then?” she snaps.

“I can’t.”

All this time I’ve wanted to share stories with her but now …

“It better not be because you feel sorry for me,” Celia says in a low growl.

“It’s got nothing to do with you, Celia,” I say. “The police are after me.”

“Oh,” she says finally.

By now it’s past midnight. Everything is still but for a night bird out on the lake.

I walk close to Celia as if we’re old friends on a lark, as if she’s Chloe and we’re in the middle of another crazy adventure. Jerry Lee looks up at us, surprised.

“We are just two friends from Newport, out after curfew. Two restless girls and a dog,” I say, and Celia leans into me.

We follow the narrow road along the western shore of Lake Memphremagog. But before we get to where the road ends I stop, the hairs rising on my neck. There’s a white car about a quarter mile ahead of us, parked in the road.

I take Celia’s hand and guide her down a hill, behind a shed. “I think there’s someone in that car.”

“It’s just parked there,” Celia whispers.

“Humor me,” I urge.

“For how long? We’re so close, Radley.”

“How much would it suck if we get picked up now, Celia, within sight of Canada?”

Celia sighs, sits down with her back against the shed, and pats the ground for Jerry Lee. But Jerry Lee remains standing at attention beside me.

We watch for only a minute or two, and then, slowly, silently, the white car begins moving. An industrial-strength flashlight pans across the fields on either side of the road, as if the driver thinks he’s seen something. The beam probes the perimeters of the shed, but we are well hidden. Still my heart thunders. The car moves particularly slowly as it comes parallel with us.

But it keeps going, heading away from the border, back in the direction of town.

As soon as the tail lights vanish, we tear up onto the road and this time we are running.

In moments we arrive at a metal guardrail.

It’s clear we’re meant to stop.

But we don’t stop. We keep going.

Climbing over the rail on the American side, we blaze through a swath of underbrush to another rail thirty feet away.

And just like that, we’re over the border.

We are exhilarated, continuing on pure adrenaline. We pass a farm occasionally as we move deeper and deeper into Canada. Mostly, we are flanked by dense trees.

“We should get some sleep,” I say at last, stumbling over my own feet.

Celia nods and a few minutes later she and Jerry Lee lead the way into the woods. Her instincts are good. She finds us a comfortable patch of ground to spend the rest of the night.

We begin traveling by day again.

I’ve been wondering what would happen once we crossed but I’ve been afraid to ask. Not that Celia would have answered.

But I try now. “Do you want to stay together now that we’re over?”

She nods. It’s the closest we’ve come to friendship. But I’m afraid to push her. I’m learning to be quiet.

Stopping at a brook, we kneel and drink.

“Why are the police after you?” she asks.

“I don’t know. Something to do with my parents, I think. They’ve been really public about their opposition to the American People’s Party from the start.”

Celia nods.

“What about you?” I ask. “Why are you running?”

Celia shrugs.

And that’s all I get.

We have no plan.

We simply move together for another week, heading west and north.

All the signs are in French. Celia relies entirely on my translations.

When the road we’re following ends, we begin to blaze a path through dense forest.

Celia sets the pace and we continue slowly, over rugged terrain, for another two days, eating what I have left in my backpack, until we reach an abandoned place deep in the woods.

There’s an old sign over the front door. “School of Hope,” it says.

“Home sweet home,” Celia declares.

“I’m not sure about this, Celia.”

But Celia is sure.

She’s finished walking.

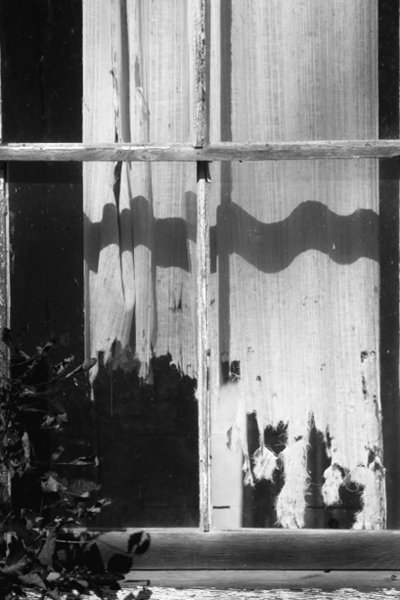

The paint, where there is paint on the school’s exterior, is chipped and dulled to a dirty gray. Several mismatched windows reveal stained shreds of curtain. No stack for plumbing, no chimney for a stove. I think this is what realtors call “rustic.”

The glass in one of the windows is missing. I approach cautiously and peer inside.

“No one here,” I announce. “Probably hasn’t been for a long time.”

“Shocking,” Celia says softly.

I ignore her sarcasm. “I think we can get in through a window.”

But Celia lifts a rock from the ground. I think she’s going to use it to break more glass, but she studies it instead, puts it back down and picks up another. She lowers the second rock and after scanning the ground with her eyes, she begins to explore the level surfaces of the schoolhouse.

“Hah!” She sounds quietly triumphant. Jerry Lee’s tail wags.

Celia holds up a key she’s found on a ledge above a window.

The lock is stiff and it takes some effort but the key eventually turns and the door opens.

Rodents and birds have been the sole students at this school for some time. It smells foul. Dried animal droppings litter every surface. We have nothing to sweep with, nothing to scrub with. Still, using what the surrounding woods offer, boughs, and leaves, and brook water, using our ingenuity, we begin to bring order.

The entire structure consists of two rooms, each about ten feet by twelve. One of the rooms contains a rusted metal bed frame with a stained piece of plywood suspended on the narrow rim where a box spring and mattress might go. The mattress and springs are gone, but I am so grateful for this bed frame, dismal as it is, set at an angle in the middle of the floor of an old country schoolhouse.

Celia and I hardly talk.

We just work together, making the abandoned schoolhouse habitable.

By the end of the day the outside looks unchanged.

But inside, a sanctuary emerges. I gather armfuls of fresh grass and cattails from nearby. We pile them inside the metal frame on top of the plywood and I spread my old blanket over, tucking it in on all four sides.

When the sun sets, wordlessly we agree to share the bed. We sink down, grass spilling over the sides. The blanket emits an almost human sigh beneath us.

I am so hungry. Our bed makes me long for green salad.

And my fingers itch for Jethro’s bear, nestled inside my backpack. But the bear hasn’t been out since Celia and I started traveling together.

Unable to fall asleep, I grieve for my empty hands.

I grieve for not finding my parents on the way to Canada.

I grieve, worrying I may never find them again.

Celia, still on our makeshift bed, sits up and inhales the fresh air wafting through the open door. The schoolhouse, on this sunlit morning, has begun to take on the scent of girls with wind-blown hair, with seeds in their pockets, with road-hardened feet.

“I’ve got food,” I say and empty my backpack of the bits I’ve gathered from several kitchen gardens: baby lettuce, baby peas, baby radishes.

We devour the tiny pile of food.

“When did you have time…?”

“I went out early, while it was still dark.”

Celia’s wild, thick hair strains to free itself from the rubber band confining it. “Who would build a school out here in the middle of nowhere?” she asks, nibbling a small, peppery radish.

“We’re not as far off the beaten track as you think,” I say. “Once you get out beyond these woods it’s small farms, some houses, a little town called Sutton. Maybe, a long time ago, kids followed a path to school here, but there are no paths leading here now.”

And if we’re to remain hidden and safe, we’ll have to keep it that way.

Hunger drives me out of bed each morning, hours before dawn. I explore the area while Celia sleeps. She has no interest in coming out with me. Or even in going out on her own.

Celia says she’s walked enough. She’s not taking another step.

From all appearances the Canadian government remains stable despite the chaos in the U.S. But Celia and I are here illegally. Even with my passport I would be thrown out of this country. I’ve crossed the border without asking permission, I’m here for an indefinite period, and I’m wanted by the police in my own country.

It feels safest to keep as low a profile as possible, traveling a different route each day.

This early in the season, the vegetable gardens are barely producing. I make my way to Sutton, instead, and creep up to a Dumpster behind a small café.

A woman, about ten years younger than my mother, surprises me in the act of lifting the Dumpster lid. She has padded up behind me so silently.

I freeze, certain she will turn me over to the Canadian police.

When I open my mouth to plead for her silence, she holds up a hand, a gesture that signals me to wait, and she flies back through the rear door of the restaurant.

I have no idea what she wants but I can’t risk finding out. I flee the moment she turns her back on me and run from Sutton empty-handed.

Consequently, Celia and I have little to eat the rest of the day.

I think about using what few coins remain of my money to buy food, but it’s American currency. It would give us away instantly.

Celia is so pale; she seems to grow thinner each day. I feel like I’m responsible for her and that scares me. In the past, I’ve blown it big-time when it comes to being responsible. I always screw up. Until now my parents have bailed me out, made things right again, as right as they could. But my parents aren’t here now.

And somebody has to keep Celia alive.

I’ll do what I can.

For days I’m afraid to return to Sutton, afraid to venture out at all, afraid the woman from the restaurant has reported me. That the Canadian police are watching for me.

I plunder a garden not far from the schoolhouse. The vegetable plot sits like a small brown package in a field of green grass. Moving through the young lettuce and onion plants, I take only a handful of greens, then slip inside the barn searching for anything else.

I find root vegetables left over from last year and “borrow” a dented pail to carry back to the schoolhouse the lettuce and onion greens, four withered potatoes, and six soft carrots.

Celia eagerly falls on the carrots. We make a meal out of raw, desiccated vegetables, and fresh lettuce and onion tops.

“Why aren’t you with your parents?” Celia asks.

I tell her we were separated. That I was out of town when all this started. I’m not sure why I’m afraid to tell her the truth, to tell her I was in Haiti. I think maybe she won’t approve. Maybe it makes me sound too rich, too spoiled. I don’t know what made me think I could help down there, anyway. I bathed dusty toddlers in plastic buckets. I braided thick hair and buttoned thin shirts. I spooned cornmeal mush into bowls. I did what I could. But the kids did ten times for me what I did for them.

Celia gnaws on a raw, soft potato. When I ask her why she isn’t with her parents, she shrugs and keeps gnawing.

I’m getting to know those shrugs pretty well. And the uneasy silence that follows them.

I offer a potato to Jerry Lee. With one sniff he refuses my generosity, asking to be let out instead, where he chases down his own food.

I roam the countryside alone. Celia never comes.

She has no idea where I go. She just knows when she wakes, there’ll be food waiting.

Though I’d like his company, Jerry Lee never leaves Celia’s side. Except to eat. The only time he ever left her was the time he retrieved me from the porch and got me to follow him into the woods. And he only did it then to save Celia’s life.

Several days in a row I fail to find enough food to satisfy us. Celia has trouble holding down the little I do manage to bring.

Even Jerry Lee doesn’t seem to be eating enough.

I want to go back to the Dumpsters in Sutton. It’s the way I’ve learned to survive. But Canada will surely deport me if I’m discovered. And then Celia would be left alone, not knowing where I am.

My feet bring me back instead to the farm where I found the withered carrots.

To my surprise, instead of police, what awaits me in the barn, in the place where I found (and stole) the dented pail, is a bar of soap, two men’s button-down shirts, a pair of overalls, a pair of green trousers, and a paper bag filled with pods of fragrant green peas.

The clothes are worn and patched. But they’re clean. I gather them into my arms and the smell of fresh laundry gives rise to a wave of homesickness. I stand in the barn, frozen for a moment, aching for my mother.

Is it possible these have been waiting for me? Is it possible someone is trying to help?

Quickly, I gather the clothes, the soap, the peas and head back to the schoolhouse before sunrise.

Celia sleeps deeply.

I shake her shoulder. “Look what we’ve got.”

She’s startled by the sudden wakening and swats at me.

After swearing for a minute, Celia pulls herself together.

She is amazed at what I’ve brought.

We hold the clothes up to ourselves. They won’t fit either of us but it doesn’t matter. We’ll make them work.

“I’m using the soap before I put on new clothes,” I say.

I draw Celia far enough from the schoolhouse to wash in the cold, clear brook that runs nearby. We put on our fresh things. Then sit on the schoolhouse step in the June sunshine, drying off, warming up, side by side.

“Celia, if I don’t come back some day…”

“You’ll come back.”

“But if I don’t, it’s because I’ve been caught…”

“I know,” Celia says.

“Will you be able to manage?”

Celia looks up at the sky. She nudges me with her bony shoulder. “You’ll come back.”

“But if I don’t?”

Celia gets up and disappears inside the schoolhouse with Jerry Lee.

Conversation over.

“What are you thinking about?” Celia asks later, sitting down beside me on the edge of our bed.

She’s feeling better now that she’s washed, in clean clothes, with a little food in her.

I’m thinking about my parents and their packages to Haiti. How the boxes arrived filled with clothes, food, crayons, workbooks. I’d call home the moment the boxes came and let my parents listen to the sound of the children opening them. It delighted my mom to know that of all the gifts she and Dad sent, the children loved her photographs the most, especially the ones of our cat, Romulus. She’d write these comical notes on the back in her very silly French, like “Bonjour, ma petite souris. Je voudrais a manger votre queues,” as if Rom were calling the children his little mice and telling them he’d like to eat their tails.

“I’m thinking about my mom,” I say. “She’s a photographer.”

“Is that what those pictures are?” Celia asks.

I nod. “Ever hear of Parker Hughes? She’s kind of famous.”

Most people get pretty excited when they find out who my mother is. But not Celia.

“What kind of name is Parker?” Celia asks.

“What kind of name is Radley?” I answer.

“Good point. Anyway, your mother’s pictures are good,” Celia says. “I like the ones of food…”

“Wait a minute. How do you even know about the photographs…”

“I’ve seen you looking at them. I was curious,” Celia says. “I went through your pack. I like the bear, too.”

I feel a black fury descend. “I would never go through your things…”

“I know,” Celia says. And shrugs. “Anyway, your mom’s pictures, they’re really good.”

I want to smack her. I want to scream at her. I want to go to my room and slam the door in her face.

And then I look at the tiny two-room schoolhouse and the possibility that it might all collapse with the slam of a door.

And I start to laugh.

“My mom made the bear. Knitting’s a hobby of hers. She says it calms her. But the bear’s not mine. It’s just on loan from a friend.”

“I wouldn’t mind borrowing it myself from time to time,” Celia says. “Actually, I already have.”

I’m torn between feeling really pissed at her for touching my things, and moved by the fact that she’s drawn comfort from them.

“I would have thought you were too old for dolls,” I finally manage to say.

“Yeah, I can see how you’d think that.”

“How old are you?” I ask.

“Nineteen. I’ll be twenty this summer. You?”

“Seventeen. Just a baby.”

“Just a baby,” Celia echoes.

I look to see if there is any meanness in her eyes and am surprised by the tears there instead. She turns away, gets up, and goes to the door to let out Jerry Lee.

Seeing the way Celia sleeps so deeply in our grass and cattail bed, seeing Jerry Lee look less and less wary when he hears anything moving outside in the woods, my own caution begins to subside.

Instinct tells us we have found a safe haven here, in Canada, under the shadow of the rugged mountains of southeastern Quebec. Is it possible my parents have found safety here, too? That in my wanderings I’ll find them or hear of them?

There’s not always food waiting for me at the farm nearby, but there’s always something. Our Lady of the Barn is reliable in her care though she doesn’t always know what we need.

What we need most is food, every day. We need food.

I am resentful on the days when no food is left for us. How quickly I revert to the spoiled child I was at home when my mother prepared every meal. On the days when Our Lady of the Barn doesn’t come through with nourishment, I have to hustle to find enough to eat, often risking a heart-pounding race in and out of Sutton.

Sometimes I arrive too late to raid the trash there.

Observing from a hiding place, I notice how all the people on the streets of Sutton seem to know each other. I eavesdrop on their conversations. They’re so relaxed. Not a soldier, not a cop in sight. It’s so different from what I left behind in Vermont.

But these people would take note of a stranger in town, particularly one who came only to raid their garbage.

I am neither brave enough nor stupid enough to risk stealing food from Sutton in broad daylight.

But today there is no need. Today Our Lady of the Barn has been more than generous.

I find a pail of ripe strawberries.

A soft blanket.

A pair of shears.

“Thank you, O Lady of the Barn,” I whisper, gathering her gifts. “Thank you!”

As I slip through the approaching dawn I look toward the house, trying to make out the figure of our benefactress. But there is no hint of her.

After Celia and I have eaten the strawberries, tossing three to Jerry Lee and watching him leap and snap the ripe red orbs out of the air, the sun is well up. With the pair of shears, Celia and I give each other haircuts out on the step of the schoolhouse. The breeze takes our locks scudding away amid the tall grasses and weeds.

We head down to the brook, and using the soap, we shampoo the stubble that is left on our heads.

Celia is better at cutting hair. Back at the schoolhouse, when I look at my reflection in the bowl of my spoon I am a pixie-headed stranger.

Celia does not complain but she looks as if I’ve cut her hair with an eggbeater.

“It’s not your fault,” she says. “It’s my hair. It has a mind of its own.” She rolls her eyes and we laugh.

At last we are free of all that weight, of its smell, of its itch.

Along with the hair, the rest of our reserve falls away.

I don’t have to ask. Celia simply starts talking. My starved ears savor her every word. My brain, at full attention, memorizes each thing she says, each story she tells. It’s as if she’s heard my questions all along. Now she’s finally ready to answer them.

“I’ve got two half-sisters back in Windsor,” Celia says. “I had a brother, but he died.”

“Your parents?”

Celia shakes her head no. Her chin juts out, a little gesture of defiance or self-control … I’m not sure which.

She stretches as if dislodging some memory. “How about you?” she asks. “Sisters? Brothers?”

“Only child,” I say. “It’s good. You don’t have to share.”

“Sharing was never the problem,” Celia says.

“What was the problem?” I ask.

Celia raises her eyebrows. “Not remembering my father. Having a drunk mother. Then having no mother at all.”

“Sorry,” I say.

Celia shrugs. “Stuff happens.”

But stuff like that never happened to me.

When there is no food waiting in Our Lady’s barn, when I am too late to slip safely in and out of Sutton, I forage for food in the woods near the schoolhouse. I never manage to bring home enough to fill us. But at least there is almost always something to chew on.

“The plants are just a little different here,” I tell Celia, gnawing on a sassafras twig. Its root beer taste helps keep the hunger at bay. All of those walks I took with my parents so many years ago must have made some impression. More and more I begin to recognize plants, develop a sense of what is edible, what is not. When I’m uncertain, I hold whatever I’ve found … a leaf, a mushroom, a berry, a root … against the underside of my arm, then against my lips, then on my tongue. Only after that will I take the smallest bite.

Celia has trouble keeping certain things down. I think it’s my fault, though I never seem to get sick.

“Have you always had trouble with your stomach?” I ask.

Celia shrugs, her way of letting me know she doesn’t like the subject. She hates admitting weakness of any sort. This I’ve learned quickly in our short time together.

Today we sit on the step of the schoolhouse and munch small, tart berries.

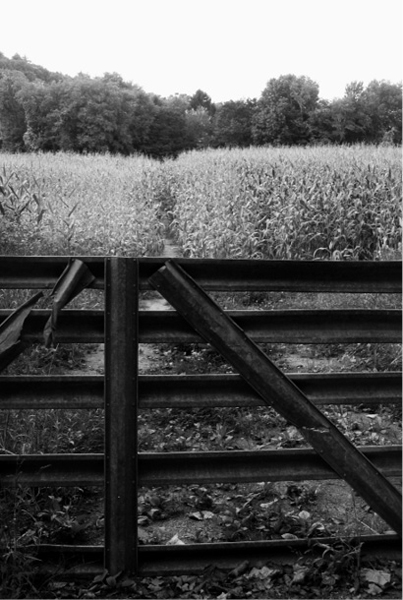

“There’s this place in Brattleboro,” I tell her. “A corn-field at the top of a trail. Through the winter, even in spring and early summer, before the corn gets too high, you can stand in the middle of it and see for miles and miles.”

Celia squints at me, her pale eyes studying me intently. “I like the way you say things, Radley.”

I shrug, offer her some sassafras to go with the berries. She accepts with a nod.

“Not far from here there’s a path up into the woods,” I tell her. “It’s steep once you get in there. Not as bad as those last few days before we got here. But steep enough to keep your heart pounding. Sometimes the mist clings to the trees in there and I feel like I’m walking in the clouds. It’s pretty amazing. Definitely worth the effort. You’d like it, I think. You should come along sometime.”

Celia wraps her arms around Jerry Lee and rests her chin on the dog’s furry back. “No,” she says. “I don’t think so.”

“Did you tell anyone you were leaving,” I ask Celia one night as we wait for sleep. “Any of your family, friends?”

“No one,” Celia says. “Maybe a few people are wondering where I am. But not many. When I was younger my cousins and I would go to my grandmother’s house a couple times a year. Most times we kids would go out on the street and leave the adults in the house to drink and fight. It was fun having all those cousins around. Then my grandmother died and everybody sort of lost touch. With you, Radley, it feels kind of like when the cousins came.”

“Well, we’ve certainly left the house so the adults can fight.”

“Pretty big house to walk away from, the whole United States,” Celia says.

“Pretty big fight, too,” I say. And I wonder for the thousandth time where my parents are.

I’m at the brook, washing dirt off and picking worms out of vegetables left for us by Our Lady of the Barn. I don’t know why I bother. The worms won’t hurt us.

Back at the schoolhouse I look at the meal we’ve put together on the rough table. Celia has fashioned a little centerpiece from bits of things she’s found. This primitive little place of ours is such a sharp contrast to my parents’ elegant home.

I think about the differences between Haiti and the house on Channing Street, and this schoolhouse in the woods of southern Quebec. I’ve been a different Radley in all three places. I’m not certain which is the real Radley.

“I never knew how much people judged you by your appearance or where you lived until all this started,” I say.

“You’re kidding, right?” Celia says. “Even you can’t be that innocent, Radley.”

“I know. It’s just that as far as I could tell, my parents never judged anyone. And they really rode me when I did it.”

“Okay.” Celia shrugs. “Maybe there are a few people in the world who don’t judge you by what they see on the outside, but only a few.”

The broccoli barely hits her stomach when Celia tears out the door. I know she’s throwing it up. I save half of mine. Maybe she’ll be able to hold something down a little later.

After she returns, I’m frightened by how pale she is, how frail she is.

“Celia, do you think we should turn ourselves in? Maybe you should see a doctor…”

“You’re crazy, Radley.”

“If you’re hungry later … I couldn’t finish…”

Celia is silent. Her temper usually flares when she thinks I’ve intentionally done something kind for her. I can see irritation written on her face. But rather than fight with me, she storms out and sits on the step with Jerry Lee.

Stomping away like that, it’s just what I used to do to my mother all the time. I wish I could apologize to my parents right now.

By my calculations it’s early July. The sun is fierce. The air drips with humidity. A mist of hungry insects swarm, pinning us inside the schoolhouse, which is oppressively hot and stuffy. Even inside we’re not free of bugs. But there are certainly fewer inside than out.

Whenever the day is close like this the wild animal stench we first encountered when we opened the place returns, rising out of the wood.

We stretch out on the splintery floor and gaze at the ceiling with its stained and busted tiles. I miss my parents so much. I wonder what’s going on in the States now. In our little schoolhouse at the edge of civilization we are so isolated from the rest of the world. In some ways I’m grateful for the peace of it. In some ways it fills me with despair to be so cut off.

“Do you ever want to just give up, Celia?” My voice is barely above a whisper.

“You mean turn ourselves in?”

“No,” I say. “I mean really give up. You know … off yourself.”

I turn toward her and see a shadow pass over her face.

“Do you have a boyfriend?” Celia asks.

“No. Why?”

“Just wondering.”

“Do you?”

Celia gives a quick shake no and is quiet for awhile.

Finally, she turns to face me. “I could never kill myself, Rad. I like fried onions too much.”

I feel something shift inside me and suddenly I’m lighter. I don’t know how she does it.

“Celia, we don’t have fried onions. You couldn’t keep them down even if we did.”

Celia smiles. It’s a strange smile. “Possibly the only thing I could keep down.”

I promise myself a trip to Sutton later, after dark. I vow to check every Dumpster and trash bin until I find what Celia’s longing for.

To pass the time, I tell Celia about the cowgirl dress from my grandmother. I describe it in all its hideous detail.

“But, Celia, I swear I’d wear it every day if only I could have my old life back again.”

Celia snorts. “A cowgirl dress? Really? You’d wear it every day?”

“Yup.”

“Forget the police, Radley. You’d better be watching out for the fashion guards.”

The two of us in our worn farm clothes and our chopped hair, stuck inside a rotting, mildewed schoolhouse, begin to laugh. Celia holds her stomach and rolls on the floor with glee. I hear a sound coming from her I’ve never heard before. I’m not certain Jerry Lee has heard it either. He butts her over and over again with his head.

When we finally grow still, the silence is unnerving.

“Tell me where you really were when all this started,” Celia says.

And I tell her about Haiti. I tell her how I had no idea what I was getting into when I went there. How there wasn’t enough food, or water. I tell her how the orphanage was an old, abandoned schoolhouse. “But nothing like this one. The kids couldn’t even go outside the gate.”

I fall silent, thinking about Celia not venturing more than a few feet from the schoolhouse door. I wonder if she’s thinking the same.

“I wish I could build them a new orphanage in a safe neighborhood where they could grow their own food, have clean water.

“They sleep on these flimsy cots, Ceil.

“Each night I would go from child to child for their bedtime hugs. I don’t know if anyone hugged them before I came. I don’t know if anyone hugs them now that I’ve gone.

“Celia, there were so many children, there was so much need. There was this little boy, Jean-Claude. He was maybe four. He would tell me he had a stomachache when really he was just hungry. I’d rub his back to comfort him the way my mother rubbed mine when I was small.

“Jean-Claude had lived on the streets for months. No one knows what he endured before he came to the orphanage. He wouldn’t talk about it. He couldn’t talk about it.”

Just like you, Ceil, I think. But I don’t say that out loud.

I gather a handful of daisies on my way back to the schoolhouse with the soggy onion rings I’ve found for Celia.

My mother loves daisies. When I was small and we were living from paycheck to paycheck, Mom made do with less food so she could buy daisies at the grocery store. It never occurred to my mother that she could go out and pick wild daisies. That she could have them for free.

She would often leave a jar of them on the nightstand beside my bed. I hated daisies. I hated the way they smelled, particularly after they started to slime.

Now I gather daisies. I pick a handful with their white-slip petals and their tawny eyes and place them in a bottle I’ve found by the side of the road. I bring them to the schoolhouse and set them on the floor by our bed.

Celia eats only a bite of the onion rings, then pushes the rest away. Moments later she’s outside heaving her guts up.

“I guess I was wrong,” Celia says. “About being able to hold down fried onions.”

“Don’t tell her,” I whisper to Jerry Lee, “but I hate when she’s wrong.”

Celia comes over, kneels, wraps her arms around Jerry Lee’s chest, lays her head gently on his back, and sighs. “I hate it, too.”

Celia loves movies, particularly action and animation. I love movies, too, mostly fantasy and comedy and love stories. We alternate telling movie plots to each other.

Occasionally we hit on a movie we have in common. Or an entire series … like the Harry Potters.

It is then, particularly, we see how in some ways we are so alike.

Our Lady of the Barn leaves a copy of the Montreal Gazette for us. My French is pretty good but I’m still glad to have an English-language newspaper.

I fold it carefully and carry it home along with the fresh vegetables she’s left. I handle the newspaper like a holy relic. Not only does it tell us the date (July 12) and the weather forecast, but it connects us to the outside world.

I read aloud to Celia while she stares out the window. A half-dozen letters to the editor debate the subject of civil rights under emergency law. Eyewitness reports describe overcrowded U.S. prisons and outbreaks of disease. The paper says American television transmission is mostly down, newspaper publication spotty, and access to the Internet completely unreliable; it’s hard to say how rampant the looting, violence, and general criminal activity truly is. All the news from the States is anecdotal.

In the classifieds, people advertise safe houses and I ask Celia what she thinks.

“I think about that sleazebag who tried to pick us up in Vermont. I think we’d be crazy to risk it.”

I wonder how many others there are, people like us trying to survive, relying on the kindness of strangers. I wonder how many have trusted the wrong people.

I pray my parents haven’t trusted the wrong people.

How I wish to see her, our benefactress.

At dusk, lingering in the woods a safe distance from the barn, I wait. Finally, well after dark, I catch sight of her. By the light of the moon an ancient woman with a stooped back shuffles through the unkempt garden. I listen as she talks to the weeds, to the plants, to the clods of dirt. I watch her move from the garden to the barn, from the barn to the house. She never switches on a light.

After she disappears into her home, I enter the garden where the gate hangs on one hinge. Weeds grasp my ankles. Something sharp slices my skin. How did the old woman move through here so smoothly?

Back in the barn I find a dimpled rump of cauliflower waiting for me.

I place Our Lady’s offering in my rusted bucket and scratch a note into the wood with my pocket knife. “Thanks.”

Celia and I divide the head exactly in half. I tell her everything I have seen and each bite of spicy white cauliflower tastes like a miracle.

“You could pull weeds for her,” Celia suggests.

I nod. “You could, too.”

“No,” Celia says firmly.

“No?”

“No.”

Something in her tone makes the hair lift on my neck.

“Why? Why don’t you ever leave this room?”

But Celia has nothing more to say.

It’s midday. I’ve managed to get Celia back to the brook behind the schoolhouse by telling her I refuse to wash her underwear. If she wants clean knickers she’ll have to scrub them herself.

How did she have the courage to travel all the way from Windsor, when now she’s afraid to go five yards from the schoolhouse?

We hand wash our clothes in a circle of sunlight. The sliver of soap from Our Lady of the Barn is nearly gone. I hope soon she remembers to leave more.

“I like it here,” Celia says.

“Here? By the brook?”

“No,” Celia says. “Here. This life. Canada.”

I shake my head. “Celia, you never leave the schoolhouse. You can’t go more than twelve hours without throwing your guts up. But you like it here?”

“Yeah. I do.”

“Why?” I ask. “Why do you like it here?”

“I feel so free here.”

“Free?”

“Yeah. I don’t have any history here. No one judges me. And you feed me. I feel like someone’s taking care of me for the first time in my life. I have no responsibilities. It feels good.”

“You’re responsible for Jerry Lee,” I say.

“That’s never felt like a job. Besides, Jerry Lee can take care of himself.” Celia smiles fondly down at the dog, who gazes back at her just as fondly. “In my whole life, he’s the only one I’ve ever been able to count on. Until you.”

I don’t say anything. I just keep rinsing out my bra. I have only the one and I’m careful with it. What can I say anyway? You shouldn’t count on me? I’m doing a crap job of taking care of you? You vomit up everything I ever bring to you?

And then, out of the blue, she says, “You know what I really miss, though?”

She doesn’t wait for an answer.

“I really miss tuna sandwiches.”

I burst out laughing. She can hardly keep water down, nearly everything she puts in her stomach comes back up again, and yet the thing she likes to talk about most is food, either fried or swimming in mayonnaise or butter.

My fingers fumble and my clean, wet bra lands in a patch of brown pine needles. First I try picking the needles off, but there are too many. I slap the bra back into the water to rinse again.

“I miss tuna fish sandwiches, too,” I say.

My mind goes leaping to my parents’ kitchen and my mother draining a can of tuna over the sink and Romulus rubbing against her leg, crazy with wanting.

“I like it with those crispy fried onions on top,” Celia says. “You know the kind that come in a can? You know which ones I mean?”

I nod. Why am I not surprised?

Our situation feels less perilous with each week we’re here. The Canadians don’t seem to have the will to hunt us down, to send us back. I start venturing out in daylight. I’m familiar enough with the area, I know where the dogs are, where the people are. I feel safe walking these roads. When a truck putters past, the driver waves. I wave back. In a strange way I feel accepted.

It is much better out in the open. Staying inside that schoolhouse during the hottest part of the day drives me insane. I don’t know how Celia bears it.

One day four ducks follow me from a pond on my way back to the schoolhouse. One comes all the way to the edge of the woods before noisily returning to its comrades.

I begin thinking about eggs. How long has it been since I’ve eaten an egg?

In the latest Montreal Gazette it says that typhoid, dysentery, cholera, tuberculosis, influenza, pneumonia, polio, and nearly every other ailment known to mankind—diseases once conquered—have broken out in the overcrowded prisons back home. People have died. It’s unclear how many. All the money we donated as a family at Christmastime over the years to CARE and Doctors Without Borders and UNICEF, we never imagined a need like this in our own country. Who could have?

It feels as if I’ve just fallen asleep when a fierce storm crashes down on us. Thunderstorms terrify me. When I was little I’d go rigid under the blankets on wild nights until my mother came, her feet so cold as she slid in beside me, the rest of her so warm. Romulus would follow her and the three of us would cling to each other as the storm raged outside.

Celia stands at the open door in a white shirt and bare legs, facing into the wind, into the fury. Seeing her ghostly figure outlined by spasms of lightning, I say nothing. I am filled with terror. I am filled with awe.

An occasional rumble of thunder still rolls over our roof, but mostly the storm is snapping its teeth a safe distance from here. The air around our schoolhouse has cooled. It smells sweet.

Celia slips back under the blanket. Her feet are freezing. So is the rest of her. She plucks Jethro’s bear from where it teeters on the edge of the bed and holds it close.

I don’t know what makes me do it. I open my arms to her the way my mother would have done. And Celia does not turn away.

“I could have stuck it out in Windsor,” she says, shivering. “I didn’t have any complaints with the APPs.”

Celia sighs. She doesn’t often sigh. “I dropped out of school when I was sixteen. Did I tell you that?”

I shake my head no.

“People think they know you. What you said the other day about people judging you, it’s so true.

“In Windsor there was this guy. He ate at the diner where I worked. Always asked for me. I had a few regulars. Most of them I liked well enough. But this guy was a pain, always sending things back because they weren’t right. And a lousy tipper. A real asshole.

“One night, after I locked up the restaurant, he was waiting for me outside. It was late, no one else around. He grabbed me and dragged me down the bank. I thought I was strong. I wasn’t strong enough.”

A long, ragged breath escapes from Celia.

“He…”

She swallows and tries again.

“He…”

But she is unable to put into words what he did to her that night. She doesn’t have to.

“That’s the night I left Windsor. I went back to my place only long enough to shower, put on fresh clothes, and get Jerry Lee. You found me in the woods a few days later.”

Now I understood why she never left the schoolhouse. Why she locked herself inside when I was away. Even with Jerry Lee by her side to protect her.

“Are you pregnant?” I whisper.

“No. No. I can’t be.” And another sigh. “If I ever see him again I’ll kill him.”

I take her hand in the dark to warm her, to comfort her. “Don’t worry,” I whisper. “I’ll be right beside you. You won’t have to do it alone.”

I wake feeling crushed by what Celia has told me. But she acts the same as always. So I follow her lead.

Out foraging, I discover a mulberry tree. Picking and eating, filling the dented pail, I am grateful to have the sun on me, to have birds winging in and out of shafts of light, and insects leaping through the tall grass. The beauty of the day helps dispel the ugliness revealed the night before.

My mother would pick mulberries from the tree behind our house every summer. She would bake the berries into pies.

I can’t bake a pie. Even if we had an oven here I couldn’t bake a pie. I never followed my mother into the kitchen. There was always something else I’d rather do.

When this is over, I will enter my mother’s kitchen with my sleeves rolled up and I won’t go away until she’s taught me everything I should know about baking a pie.

And everything I should know about everything else, too.

How she’ll laugh when I tell her that one day, in the midst of this ordeal, all I wanted in this sunlit moment was to be in her gleaming kitchen, wearing an apron, standing beside her, the two of us up to our wrists in flour.

At night I dream of being hunted.

Celia has nightmares, too. She thrashes in the bed and once or twice she’s punched me hard enough to raise a bruise.

After three nights in a row of being woken by Celia crying out in her sleep, I say, “Enough. You have to get out of here. You’re losing your mind.”

And later that morning I lead Celia and Jerry Lee to the pond with the curious ducks. It’s not much of a pond, mostly weeds and bracken, but the sky is cupped in its watery palm, and the sun warms us all the way to the bone.

“Breathe it in,” I tell Celia.

Her skin is so pale, her mouth so grim. She’s clearly uneasy being this far from the schoolhouse. But she nods and draws the fresh air into her lungs.

Side by side, we study our reflections in the water. In our dun clothes, with our wild, spiky hair we resemble two enormous nestlings blown from a tree.

Our Lady of the Barn has left two live chickens.

Chickens!

Along with a basket to carry them.

And a plastic tub with food for them to eat.

We move the bed into the front room and turn the far room into a chicken yard. Jerry Lee shows a doglike interest in chasing the chickens and they run and hide from him between my legs.

When Celia speaks sharply to him, Jerry Lee tucks in his tail and slinks guiltily back to her side.

“You’re crazy, you know,” Celia says, watching me clean out the back room. “It can’t be healthy to live in the same house with chickens. Why don’t you make a yard for them outside?”

Though I feel safe now walking along the road, encountering people from time to time, I still think it’s better our home remains secret.

“If we make a yard for them outside someone might see. They’ve got to live inside. I’ll clean up after them. What should we name them?”

Celia rolls her eyes and leaves me to my housekeeping.

I remember the barnyard photographs my mother took a couple of years ago. She won an award for them.

As I pull up splintery floorboards in the back room to reveal the dirt beneath, I talk to the chickens. “My mother would be so happy to see you guys,” I murmur. “Maybe even happier to see you than to see me.”

“That’s not true,” Celia calls, challenging me.

“What’s not true?” I call back.

“About your mother.”

I have to rewind to what I’ve just said. Ah, about my mother preferring the chickens to me.

“How do you know what’s true about my mother?” I ask Celia. “You’ve never met her. Believe me, she never saw a chicken she didn’t love. I, on the other hand, have not always been the model daughter.”

The floorboards are beyond filthy, the dirt beneath the wooden boards totally disgusting. The chickens are constantly under foot and the work of preparing a “yard” for them in the sweltering schoolhouse has me feeling more than a little testy. All these rusty nails and beer cans; I’m grateful I got that tetanus booster before leaving for Haiti.

Celia says, “I’m willing to bet your mother loves you more than any chickens.”

Now it’s my turn to roll my eyes. But I think about my mother pacing in the front hall when I arrived home hours later than expected. I remember the generous amount on my dinner plate and the tiny portion on Mom’s when money was tight. I remember finding her weeping silently on the sofa after we’d fought. I remember the forgiving touch of my mother when she kissed me good night, her gentle movements through the house when she nursed me through illness. I remember that whenever I asked for her attention, she stopped what she was doing and gave it to me.

Celia interrupts my thoughts. “It’s the way you do things, Rad. The way you took care of me when we first met. The way you’ve taken care of me ever since. You knew how to do those things because your mother does them for you. That’s how I know how much she loves you.”

I sit watching the chickens pecking happily away in their new luxury indoor chicken yard.

I don’t want to admit it but Celia’s right.

“I’m thinking,” I tell her, pretending to ignore what she’s just said, “I’m thinking the chickens’ names should be Wynonna and Ashley. Ashley’s the red one.”