In 1956, psychologist Jack Brehm asked housewives to rank how much they wanted certain household items. Then Brehm asked them to choose between items they’d rated equally desirable, perhaps a vacuum cleaner and a dishwasher. Then Brehm asked the housewives to rank all the items again. In this second pass, housewives who’d chosen dishwashers found them even more desirable than they had in the first round. And they found the item they decided against—perhaps the vacuum cleaner—less desirable than before.

This is a classic example of post-rationalization: Of course you made the correct choice between the dishwasher and the vacuum cleaner, because look at their (new) difference in desirability! But does forcing a person to make a tough choice between two objects clarify a preference that already exists, or does this choosing create the preference, itself?

Both, it seems.

Researchers in London watched participants’ brains as they pondered and then rated the desirability of various vacation destinations. Then researchers forced them to choose between vacations they’d rated equally desirable.

But researchers could’ve predicted which vacations the participants would choose—they’d charted how brightly each destination lit each participant’s caudate nucleus, a region of the brain linked to anticipating rewards—and more often than not, a participant’s choice reflected what their caudate nucleus already knew. So, forcing a choice between similar vacations brought existing preferences to light.

Then participants got back in the scanner and rated the destinations again. Like the housewives, participants’ caudate nuclei lit brighter than the first time for the vacations they picked, and were dimmer than the first time when imagining the desirability of the vacations they decided against. And so, a person’s choice also creates—or at least solidifies—a preference.

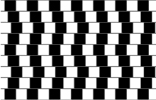

Eye Hack: Café Wall Illusion

Look at this jumble! Now look again. The horizontal lines are all parallel.