The saying, “The sun never sets on the British Empire” was true as recently as 1937, when tiny England did, in fact, still have colonies in each of the world’s twenty-four time zones. The British explored, conquered, and ruled much of the world for many years. But what made them believe they could do it?

For the first thousand years after Christ, Greece and Rome were the only nations that told stories of heroes and champions. England was just a dreary little island of rejects, cast-offs, barbarians, and losers. So who inspired tiny, foggy England to rise up and take over the world?

Hoping to give his countrymen a set of values and a sense of pride, a simple Welsh monk named Geoffrey assembled a complete history of Britain that gave his people a grand and glorious pedigree. Written in 1136, Geoffrey’s History of the Kings of Britain was a detailed account of the deeds of the British people for each of the seventeen centuries prior to 689 CE.

But not a single word of it was true.

Yet in creating Merlyn, Guinevere, Arthur, and the Knights of the Round Table from the fabric of his imagination, Geoffrey of Monmouth convinced a sad, little island of rejects, cast-offs, barbarians, and losers to see themselves as a magnificent nation.

When they began seeing themselves differently, they soon became a different nation in reality.

It has always been assumed that legends and myths, with their stories of heroes, are the by-products of great civilizations. But I believe they are the cause of them. Throughout history, the mightiest civilizations have been the ones with heroes—those larger-than-life role models who inspire ordinary citizens to rise up and do amazing things.

People will usually do in reality what they have seen themselves do in their minds. Heroes make us see grand possibilities—first we see it, then we do it.

The ideas that form the basis of Western society have their roots in ancient Israel and Persia, then Greece, whose culture dominated when Alexander the Great conquered virtually all the known world. However, because Alexander died young and left no strong government behind, the Romans picked up the pieces to form an empire that would provide us with a framework for society until the British Empire emerged.

The primary influencers have been:

• Israel and Persia in the Near East

• Ancient Greece

• Rome

• Britain

These are the societies that birthed Western culture, that odd set of ideas and values embraced by the peoples of Western Europe, North America, and Australia—those societies measured by the swinging of the Western Pendulum.

NY Carlsberg Glyptotek

Zeniths of “We” in the Past Three Thousand Years

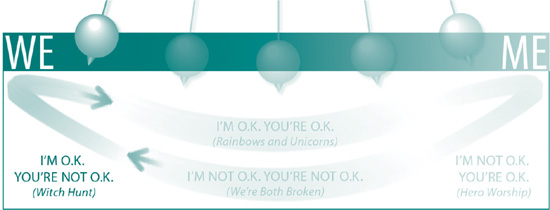

This is a list, on the following pages, of iconic persons and events that capture the spirit of the Zeniths of “We” for the past three thousand years. Many of the persons selected enjoyed a lifespan that touched both sides of the Pendulum. In these instances, the Upswing of “We” is that window of time in which they made their historic difference.

Figure 9.1 The Zenith of a “WE” Cycle.

The Law of Probability would tell us that an equal number of leaders working for the common good should be found at the Zeniths of “Me.” Consequently, an honest skeptic reading this list of “We” Zeniths might assume that we have selected data to prove our assertions. Please be assured this is not the case; rather, we created this list by asking random experts to name the persons and events in history that best illustrate “working together for the common good.” The persons polled had no clue how we planned to use the information.

We’ve listed all of the persons and events they named and added a few of our own because, frankly, even people well versed in history don’t know much about the years 300 to 800 CE. We had to dig deep in these years to find historic examples of the “We,” and frankly, the examples were hard to find. It’s interesting to note, however, that every example of “We” thinking that we discovered in our research of the Dark Ages occurred during the Upswing of a “We.” We didn’t find a single example of “working together for the common good” in the Middle Ages that wasn’t near the Zenith of a “We.” Don’t believe us? Investigate it for yourself. You’ll find that what we say is true.

The twenty-year Upswing to a “We” Zenith happens only once every eighty years. This mean the statistical odds of an event happening in this window are only one in four.

| WE | ZENITHS OF “WE” IN THE PAST 3,000 YEARS |

| 937 BCE: | Solomon, near the end of his life, learned the wisdom of serving others and told his story in the Bible’s book of Ecclesiastes, written eight years before this Zenith of the “We.” (Bible scholar Mark A. Copeland indicated that Solomon likely wrote the book of Ecclesiastes around 945 BCE, when he was sixty-six years old). Born in 1011 BCE, six years after a Zenith on the Downswing of a “We,” Solomon’s bar mitzvah happened just before the tipping point into the Upswing of a “Me.” He was thirty-four years old at the “Me” Zenith (977 BCE) and fifty-four at the end of the “Me,” when it reached the tipping point that took him into a new “We” that would Zenith in 937 BCE. He lived to be eighty years old. His Ecclesiastes is a very interesting book. |

He wrote in the book of Ecclesiastes about his self-indulgence as a young man at the Zenith of a “Me”:

ME |

I denied myself nothing my eyes desired; I refused my heart no pleasure. My heart took delight in all my labor, and this was the reward for all my toil. |

He then explained what he learned during the Downswing of the “Me.”

WE |

Yet when I surveyed all that my hands had done and what I had toiled to achieve, everything was meaningless, a chasing after the wind; nothing was gained under the sun. |

Read Ecclesiastes, and you’ll experience the reflections of an old man who had lived through a “Me” and found it to be hollow. Ending his days in a “We,” Solomon finally seemed to find the answers he sought:

WE |

I know that there is nothing better for people than to be happy and to do good while they live. That each of them may eat and drink, and find satisfaction in all their toil—this is the gift of God. |

Solomon died in 931 BCE, six years after the Zenith of a “We,” with society’s Pendulum in precisely the same position it had been in when he was born. We’ll take a second look at his life at the “Me” Zenith in another chapter.

857 BCE: Homer completes the Iliad and the Odyssey just seven years after this “We” Zenith (850 BCE). The oldest extant works of Western literature, these are considered fundamental to the modern Western canon and have been influential in shaping Western culture. Stories are written for unnamed and unseen others, not for oneself. Consequently, the creation of literature is one of the purest expressions of “We.”

Capitoline Museum, Albani Collection

777 BCE: The Olympic Games were born in the year following this Zenith, according to the Bibliotheca Historica (Historical Library) of Diodorus Siculus, an ancient Greek historian. Modern scholars consider the date reliable. During a celebration of these ancient games an Olympic truce was enacted so that athletes could travel from their countries to the games in safety. As long as they met the entrance criteria, athletes from any country or city-state were allowed to participate. The prizes for the victors were olive wreaths or crowns.

697 BCE: Hezekiah ruled Judah in Israel, 726–697 BCE. (Other sources say his reign began in 715 BCE, but either way, his reign began during the Upswing of this “We.”) To bring the people into unity, Hezekiah sent letters across Judah and Israel asking everyone to attend a Passover celebration. The event was a huge success: “There was great joy in Jerusalem, for since the days of Solomon son of David king of Israel there had been nothing like this in Jerusalem.”1 Hezekiah strengthened Judah politically, expanded its borders, and built an underground tunnel to bring water into Jerusalem in case of a siege. Most scholars consider Hezekiah one of the best kings of any society in antiquity.

617 BCE: Athenian Law is codified by Draco, a legislator of ancient Athens, in 620 BCE, three years prior to the Zenith. Draco replaced the prevailing system of oral law delivered by eupatrid thesmothetai, “those who lay down the law,” with a written code to be enforced only by a court. This was also about the time that Aesop was born in Greece. His fables would do much to accelerate the next “We” as it swung upward.

537 BCE: Cyrus the Great created the earliest known Bill of Rights in 539 BCE immediately following his conquest of Babylon. The document has been called “the first declaration of human rights, which, for its advocacy of humane principles, justice and liberty, must be considered one of the most remarkable documents in the history of mankind.”2 However, those who would prefer to disparage all things Persian have hotly contested this assessment. (Persia is current-day Iran.) It is notable, however, that this same Cyrus, according to the Bible, allowed the captive Jews to return to Jerusalem during the first year of his reign.3

The Granger Collection, NYC

457 BCE: Decree of Artaxerxes I reestablished the government of Jerusalem. Ezra, the author of the Old Testament book by the same name, spearheaded this effort. Nehemiah, the author of the Old Testament book by the same name and cupbearer to Artaxerxes I, was later sent to rebuild the city walls and restore its defenses.

377 BCE: Plato founded his Academy in Athens in 387 BCE, ten years prior to the Zenith of the “We.” In approximately 380 BCE he wrote The Republic, his world-altering treatise that concluded that justice is better than injustice. Whether or not Plato arrived at the right answers is debatable, but most people throughout Western history have agreed that he definitely asked the right questions about how people should live.

CC Image courtesy of Alma Pater on Flickr

297 BCE: The “Latin Rights” Colony of Carseoli is so designated by the Romans just one year prior to the Zenith of this “We.” These Latin Rights are significant because an early Roman conqueror defeated this same Latin League in the Battle of Lake Regillus at the Zenith of a “Me” twenty years earlier. Rome, now in a “We,” extended to these former enemies many of the privileges of Roman citizens, including the important rights of commercium (the right of transacting business and conducting lawsuits in Rome on the same footing as Roman citizens) and connubium (the right of intermarriage with Romans). In effect, Rome said, “We’re willing to accept each of you into the group as one of us.”

217 BCE: The Roman Republic chose to ignore its long-standing policy that soldiers must be both citizens and property owners. This opened the door for military service to the common man. This decision was made precisely at the Zenith of a “We.” Meanwhile in Palestine, Rabbi Judah HaNasi coordinated the redaction of the oral Torah of Judaism during the Upswing of this “We” in order to form the Mishnah, thereby saving millennia of wisdom that otherwise would have been lost.

137 BCE: Stoic Philosophy arrived in Rome just three years prior to this Zenith of the “We.” In that same year (140 BCE) playwright Lucius Accius has his first play, Atreus, performed in Rome. Most of his fifty plays are tragedies, of course, because whining about problems and sacrificing ourselves to make things better is what we do at the Zenith of a “We.” Stoic Philosophy embraces the belief that pain and hardship should be endured without a display of feelings and without complaint, saying essentially, “Pain is good. Life is pain. Crap happens and then you die. But we are doing the right thing. Oh joy.”

57 BCE: Julius Caesar (with Crassus and Pompey) used populist “We” tactics just three years prior to this Zenith to amass power within the Roman Senate. These tactics included feeding the poor (a grain dole) and limiting slavery, as slavery took jobs from poor free citizens. Caesar also garnered political support from the masses by attempting to expand citizenship to communities outside Italy.4 Caesar later betrayed the “We” and used this power to make himself dictator-for-life. When he was assassinated for this “Me” ambition, society was still in a “We,” although it was in the Downswing. Had Caesar made himself dictator during a “Me,” he likely would not have been assassinated. His successor, Octavius, later to be called Caesar Augustus, became the first emperor of Rome in the Upswing of the following “Me” in 27 BCE, halfway to the Zenith.

Musée Arles antique

23: Jesus was presumably a carpenter in Nazareth at this time. Most scholars believe he was born between 6 BCE and 4 BCE, so he would have been around twenty-six to twenty-nine years old in 23 AD, when he was about to enter the wilderness for his forty-day fast. A new prefect of Judaea, Pontius Pilate, would be appointed three years later. Five years from then, Herod Antipas would execute John the Baptist, and shortly thereafter, in approximately 30 AD, Jesus would demonstrate the ultimate “We”:

WE |

Greater love has no one than this: to lay down one’s life for one’s friends. |

103: Pliny the Younger, a consul of Rome, completed his Panegyricus and delivered it as oratory to the Roman Senate just three years prior to this Zenith of the “We.” The Panegyricus describes in detail the actions of a good leader in fields of administrative power such as taxes, justice, military discipline, and commerce.5 It served as something of a textbook for “We” administrations thereafter. It is notable that Pliny the Younger had been witness to the eruption of Mount Vesuvius twenty-one years earlier, in which his Uncle Pliny the Elder died.

183: The Decline of the Roman Empire begins in 180 AD following the death of Marcus Aurelius, the last of the “five good emperors,” just three years prior to this Zenith. The current emperor is Commodus, an out-of-control ego who believes he is the reincarnation of Hercules, frequently emulating that legendary hero’s feats by appearing in the Roman arena to fight a variety of wild animals. The absence of a dynamic “Me” leader forty years prior (at the Zenith of the “Me” of 143) had caused Rome to become unfocused and undergo an identity crisis. Remember: heroes strengthen the identity of a society.

ME |

Heroes raise the bar we jump and hold high the standards we live by. They are ever-present tattoos on our psyche, the embodiment of all we are striving to be. We create our heroes from our hopes and dreams. And then they attempt to create us in their own image. |

Just ten years after this aborted “We” Zenith of 183 CE, a conspiracy of administrators near to Emperor Commodus sent his wrestling partner, Narcissus, to strangle Commodus in his bath, and that was the end of the reincarnated Hercules. The Senate of Rome would sentence the next emperor to death after he had ruled for only sixty-six days. When a committee can murder one emperor and vote death upon the next one, that society must not only be in a “We,” but is likely floundering in the vacuum created by an absence of heroes.

WE |

A ‘We’ is about serving through small actions, but it has a dark side as well: we get tired of being good. |

263: Emperor Aurelian built a wall around Rome (270) to protect the citizens from attack. To unify the people’s religious beliefs, Aurelian chose to use the winter solstice to be celebrated as “The Birth of the Unconquered Sun.” Roman Christians opted to embrace this celebration, but with a twist: they would celebrate a different birth. Later, Aurelian would be forgotten, but Christmas remained.

343: Constantine the Great of Rome sent grain, oil, iron, and wine to the Goths to thank them for repelling an invasion by the Vandals and Sarmatians. The Romans and the Goths then enter into a treaty. This was done in 331 AD, eight years after the tipping point on the Upswing of the “We.”

Museo Chiaramonti

423: Emperor Honorius granted the title of “allies” to the Suevi/Asding Vandals6 and gave the Visigoths the best land available in Gaul to settle upon (418). Also during the Upswing of this “We,” the men who would become known as St. Jerome and St. Augustine of Hippo wrote “We” books that would influence the world for millennia.

503: “Lex Romana Burgundionum,” the Code introduced by Gundobad, King of Burgundy, gave rights to his Burgundian and Roman subjects alike. This was begun in 485, during the Upswing of this “We.” In 493 Clotilda, the Burgundian princess, married Clovis and, having embraced the Roman Rite herself, helped convert Clovis to Roman Christianity. Clovis became the first ruler (481–511) of the Merovingian dynasty, a kingdom that stretched from Northern Spain to the feet of Norway and Sweden. Although Clovis wasn’t a particularly great ruler, his conversion to Orthodox Christianity was enough to make him King of the Franks in the eyes of the pope.

583: Peace Talks between the Saxons and Celts were held shortly after this Zenith by the man who would become known as Saint Augustine of Canterbury. This effort began when Augustine traveled from Rome to Canterbury, the headquarters of the Saxon king Ethelbert. The Saxon people had a reputation for being barbaric and fierce.

663: Augustine wasn’t completely successful in his peace talks eighty years earlier, but it is interesting to note that a meaningful peace between the Celts and the Saxons finally emerged precisely at this next Zenith of this “We.”

743: The Venerable Bede, known as the father of English church history, spent the Upswing of this “We” making certain that future generations would have an accurate account of life in that place and time. Bede was worried about people he would never meet. He committed himself to benefiting all of society in a way that had no immediate benefit to himself. His most important book, The Ecclesiastical History of the English People, was written in 731. Forward-thinking actions for the benefit of all are typical during the Upswing of a “We.”

823: Charlemagne ruled during the Upswing of this “We.” The pope placed a gold crown on Charlemagne’s head while he knelt in prayer at Saint Peter’s on Christmas Day, 800 CE—the foundation of the Holy Roman Empire. Charlemagne believed the government should work to benefit those it ruled. He urged better farming methods and worked continually toward reforms that would improve the lives of the people. He even set up money standards to encourage commerce among the people. Charlemagne was not your average conqueror.

CC Image courtesy of Rama on Flickr

903: Better education and social order were the legacy of Alfred the Great, the Anglo-Saxon king during this Upswing of this “We.” Alfred believed that learning “makes life more rewarding and enjoyable. . . . the worst thing of all is ignorance.” His code of law based on the teachings of the Bible helped to maintain social order. He died in 899, just four years before the Zenith of this “We.”

983: Trial by Jury was introduced by King Æthelred just fourteen years past this Zenith. Æthelred ruled England from 978 to 1016, with only a brief interruption in 1013 when Danish Viking raiders caused him to escape to Normandy for a year. Yes, they were perilous times—all the more reason to see his institution of trial by jury as remarkably advanced “We” thinking.

1063: William the Conqueror was crowned king on Christmas Day, 1066, at Westminster Abbey following the Battle of Hastings. William’s only real distinction was that he commissioned the compilation of the Domesday Book, the precursor to the modern census, a survey of the productive capacity of the people of England.

1143: Geoffrey of Monmouth wrote Historia Regum Britanniae (History of the Kings of Britain) and, in so doing, created the legend of King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table, men who sacrifice themselves willingly in the interest of doing good.

1223: Magna Carta was issued in 1215, eight years before the Zenith of this “We,” and passed into law in 1225, two years after the Zenith. The Magna Carta was the first document forced onto an English King by a group of his subjects in an attempt to limit his powers by law. It is considered a precursor to the famous “We the People . . .” written by the framers of the US Constitution.

The Lateran Council of 1215 approved of burning at the stake as a punishment against heresy.

1303: Carta Mercatoria was issued by King Edward I. This allowed foreign merchants free entry and departure with their goods. Its message is that “A strong economy is the result of all of us working together.”

1382: Winchester College was founded.7 It is now over six hundred years old and is the oldest of the original nine schools defined by the English Public Schools Act of 1868. (Also among the nine were Eton, Harrow, and Charterhouse).8 At about this same time King Richard II attempted to rule without consulting Parliament. The forces of the Lords Appellant quickly overpowered Richard’s small army outside Oxford, and he was imprisoned in the Tower of London until he apologized and promised not to do it again.

The Boy’s King Arthur: “Sir Mador’s spear brake all to pieces, but the other’s spear held.

1463: Thomas Malory, just seven years after this Zenith, completed his own version of the resurrected stories that had been told by Geoffrey of Monmouth 320 years earlier. Malory’s tales of the Knights of the Round Table and their deeds for society glisten once more in his Le Morte d’Arthur. It is notable that the technological “We” Alpha Voice that emerged shortly before the Upswing of “We” is the printing press of Johann Gutenberg. Wikipedia reports that printing presses in Western Europe produced more than twenty million books by the year 1500. A single Renaissance printing press could produce thirty-six hundred pages per workday.9 Consequently, books by best-selling authors, such as Martin Luther, were sold by the hundreds of thousands in their lifetime.

1543: Copernicus announced that the Earth is not the center of the universe but that it, in fact, revolves around the Sun. It stands to reason that this realization and the subsequent announcement that “We are not the center of the universe” would be made at the Zenith of a “We.” Can you imagine anyone coming to that conclusion during a “Me”?

CC Image courtesy of Matthead on Flickr / Nicolaus Copernicus bust

Just eleven years past this “We” Zenith, England’s “Bloody Mary” revived the practice of burning at the stake and offers 284 Protestants as her offering to God.

1623: The English Petition of Right stipulated that the king could no longer tax without Parliament’s permission. This was passed in 1628, just five years after the Zenith. In 1624, just one year beyond the Zenith, the following words were written:

WE |

No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less as well as if a promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friend’s or of thine own were: Any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind; and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.10 |

1703: The English Bill of Rights provided freedom of speech and banned cruel or unusual punishment. These strengthened Parliament further and gave the people more rights to express themselves. It was passed in 1689 during the Upswing of a “We,” of course. This Upswing of the “We” (1683–1703) includes the Glorious Revolution (1688–1689) that established the final victory of Parliament (We) over the king (Me).

The Salem Witch Trials of 1692 began just eleven years prior to this “We” Zenith, making burning at the stake popular once more.

1783: The United States won the Revolutionary War and the US Congress ratified a preliminary peace treaty with Britain. British troops left New York City. In just three more years America’s founding document would open with the words, “We the People . . .” One of the great “We” documents of all time, the US Constitution was written on the Upswing of a “We,” of course. Just six years after this Zenith, the last article of Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen was adopted (August 1789) by the National Constituent Assembly of France (Assemblée nationale constituante) during the French Revolution.

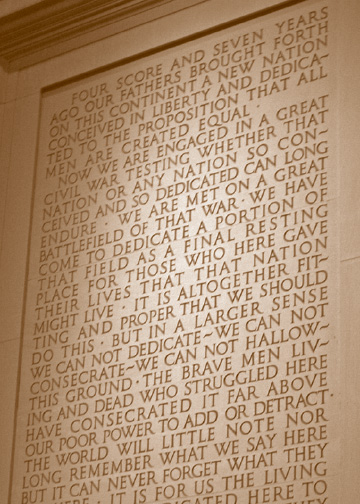

1863: Gettysburg Address, in which Abraham Lincoln stated, “Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” Just two years later, in 1865, French law professor and politician Édouard René de Laboulaye, a supporter of the Union in the American Civil War, made a comment during after-dinner conversation at his home near Versailles, stating, “If a monument should rise in the United States, as a memorial to their independence, I should think it only natural if it were built by united effort—a common work of both our nations.” Laboulaye’s comment was not intended as a proposal, but nonetheless it inspired a young sculptor, Frédéric Bartholdi, who was present at the dinner.11 Bartholdi then went on to sculpt the Statue of Liberty and arranged for it to be given as a gift to America. Emma Lazarus later wrote the poem we all know, whose lines include, “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, the wretched refuse of your teeming shore. Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me, I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

CC Image courtesy of Wknight94 on Flickr

1943: Adolph Hitler was the German promoter of “I’m OK, you’re not OK,” 1933–1945. Joseph Stalin was the Soviet promoter during his “Great Purge” of 1936–1938. Senator Joseph McCarthy was the American witch-hunt specialist with the help of the “Un-American Activities Committee,” 1937–1953.

Union membership and military enlistments reached an all-time high in the United States. In Germany, nationalism was surging, as Germans began burning books at the halfway point of the Upswing. Sigmund Freud’s books were prominent among those they burned, to which he quipped, “What progress we are making! In the Middle Ages they would have burned me. Now, they are content with burning my books.” In 1938, five years before the Zenith, T. H. White’s The Sword in the Stone was published, the first volume in the eventual quartet of books published as The Once and Future King, White’s version of Malory’s version of the Knights of the Round Table. Just two years before this “We” Zenith, John Steinbeck mocked the dreams and illusions that are part of every “Me”:

WE |

There is a story told of a Swedish tramp, sitting in a ditch on midsummer night. He was ragged and dirty, and drunk, and he said to himself softly and in wonder, “I am rich, and happy, and perhaps a little beautiful.” |

Approaching this Zenith of the “We,” John Steinbeck wrote his first commercial success, Tortilla Flat, which he considered to be a contemporary retelling of the story of the Knights of the Round Table. This is thus the third time that story has showed up at the Zenith of a “We,” and this time it showed up twice.

The Story of King Arthur and His Knights © Howard Pyle

2023: Wait and see. Or if you’re really curious, keep reading and see what the authors are predicting. (Frankly, if you’re not anticipating a resurgence of interest in the story of the Knights of the Round Table, we can only assume you’ve not been paying attention).

A “We” is about serving through small actions, but it has a dark side as well: we get tired of being good. The actions we once took willingly begin to lose their sparkle, until finally the chains of duty, obligation, and sacrifice bind us. Although we are self-righteous and proud in our service to others, secretly, it dissatisfies us. We begin to long for the freedom and rewards and dizzying heights of “Me.” Near the pinnacle of the 1943 “We,” a famous novelist made the following observation:

WE There is a strange duality in the human which makes for an ethical paradox. We have definitions of good qualities and of bad. Of the good, we always think of wisdom, tolerance, kindliness, generosity, humility; and the qualities of cruelty, greed, self-interest, graspingness, and rapacity are universally considered undesirable. And yet in our structure of society, the so-called and considered good qualities are invariable concomitants of failure, while the bad ones are the cornerstones of success. A man—a viewing-point man—while he will love the abstract good qualities and detest the abstract bad, will nevertheless envy and admire the person who through possessing the abstract bad qualities has succeeded economically and socially, and will hold in contempt that person whose good qualities have caused failure. When such a viewing-point man considers Jesus or St. Augustine or Socrates he regards them with love because they are the symbols of the good he admires, and he hates the symbols of the bad. But actually he would rather be successful than good.

iStockphoto / Mari

Near the Zenith of the most recent “Me,” women had big hair, cars were dramatic two-tone affairs, and kids were killed for their tennis shoes, as though they thought, I must own those shoes. I have no status without them.

iStockphoto / Alina555

Conversely, near the Zenith of a “We,” personal liberties are stripped away for the common good: “Do you recycle? You should. You’re not on this planet alone.” “Secondhand smoke is like a drive-by shooting. If you don’t care about your own health, you should at least care about the health of the children who breathe what you exhale.” “Your hybrid vehicle still burns gasoline, you know. If you really cared about the planet you’d ride a bike.”

iStockphoto / onurdongel

Yes, we always carry a good thing too far. In the upper reaches of a “We,” the once-beautiful dream of connectedness and working together for the common good slowly degenerates into a series of restrictions that make us feel righteous. This righteous momentum carries us into duty, obligation, and sacrifice long after the dream is over.

And now we understand why, in 1898, George Bernard Shaw quoted Shakespeare: “When a stupid man is doing something he is ashamed of, he always declares that it is his duty.”14

As Shaw approached the “Me” Zenith of 1903, he was ridiculing the legalism and restrictiveness of the “We” in which he had grown up. Ten years later, at the halfway point of the Downswing from that same “Me,” Henry Ford’s 1913 introduction of the first assembly line that employed conveyor belts was an Alpha Voice of technology that gave us a glimpse of the “We” thinking that would become mainstream in 1923.

But as we’ve already looked at the “We” Upswing of 1923 to 1943, let’s now take a look at the Downswing from that Zenith.