Chapter 1

Order of Battle – 11 th November 1918

Air Council and Air Ministry – UK Commands including Ireland, France and Belgium, Middle East and India – Wing and squadron formations – Roles of squadrons bringing them to 11 November 1918 locations

THE AIR COUNCIL AND AIR MINISTRY

Following the formation of the Royal Air Force on 1 April 1918, the Air Council and the Air Ministry were established bodies at the cessation of hostilities on 11 November that year. The new service was formed from units and personnel of the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) and the Royal Flying Corps (RFC). The most senior officers in the service all commenced their careers in the Royal Navy or the Army, many of them having learned to fly immediately before the First World War or during the war itself. As the year ended they still bore their Army/Navy ranks, and there was a mixture of uniforms.

It is appropriate briefly to trace the developments that brought about the formation of the RAF in 1918. Dominion soldiers, sailors and airmen fought alongside British forces in the Great War. And so it was appropriate to bring a South African into the War Cabinet, and General Jan Smuts was available to the Prime Minister, Lloyd George, as an adviser without any government departmental responsibilities. When the German Gotha bombers flew from their Belgian airfields to attack London in 1917, the air defences were found wanting. The anti-aircraft guns were manned by the Army and the fighter aircraft were from either the RNAS or RFC. The means of giving a warning to take cover were almost non-existent, and the fighters had such a poor rate of climb and speed that they could hardly catch the Gothas, even if they were airborne at the time. Smuts was given the task of investigating and reporting back to the War Cabinet. As a direct result of his report, the defences of London were brought under one unified command. But this did not solve the problem of inter-service rivalry in procuring the latest aircraft types or in allocating priorities in combat. Naturally the Navy would put defence of the fleet before defence of the capital, and the Army would put reinforcement of the air units on the Western Front (Belgium and France) before reinforcement of fighter defences around London. Smuts therefore went on to look into these matters, and he came up with the idea that only a single integrated flying service would stop the squabbling over resources and the allocation of flying units to the various theatres of operations. Hence the Royal Air Force came into being.

The Air Council

The Air Council in 1918 was the supreme governing body of the Royal Air Force, and it brought together the most senior officers of the service with their political masters. The Air Minister was appointed by the prime minister of the day, and his most senior service adviser was the Chief of the Air Staff. The Air Council met as required, but the Air Minister left the day-to-day running of the service to the Chief of the Air Staff and the service heads of the various departments. While governments came and went, the senior members of the RAF stayed until retirement, resignation or death, thus providing continuity of policy and direction. On the other hand, governments were formed from different political parties, and during the inter-war years Britain had, for the first time in its history, Labour governments. The Conservative and Liberal parties also formed governments, and because of the economic crises that hit Britain in the period 1930 – 35 it was necessary to form national governments from more than one political party. The changes of government, as will be seen in Chapter 16, would bring with them changes in air policy.

At the cessation of hostilities in 1918 there had been a coalition government headed by the Liberal party leader, David Lloyd George. Sir William Weir had been appointed as Secretary of State for the Royal Air Force on 27 April 1918, and he remained in that post until 14 January 1919. He was then succeeded by Winston Churchill, whose title was Secretary of State for War and the Royal Air Force. In March 1919 this was abbreviated to Secretary of State for War and Air; Churchill holding that post until 5 April 1921. In other words, Lloyd George did not want the Air to be a separate department of state. But Churchill had no intention of absorbing the RAF into the Army. Indeed, in a letter to Walter Long, the First Lord of the Admiralty, Churchill made it clear that he intended giving new ranks and titles to members of the Royal Air Force as if to emphasize its existence as a separate arm of the British services, ranking with the Royal Navy and the Army. The Chief of the Air Staff on the Air Council at the cessation of hostilities was Major-General F.H. Sykes CMG, although he was not the first incumbent, as Major-General Sir Hugh M. Trenchard had resigned the post over a policy disagreement with Lord Rothermere. Trenchard, being so senior a member of the service and one of its founder members, could not be allowed to do nothing, and he was placed in command of the Independent Bombing Force on the Western Front. This was his opportunity to employ the bomber in a strictly strategic manner, i.e. to bomb targets removed from the battlefield, targets behind the enemy lines and industrial targets in Germany itself, with the intention of reducing the enemy’s ability to wage war.

Lloyd George.

The other members of the Air Council provided direction and policy in matters of personnel, aircraft construction, supply and organization, with a Permanent Under-Secretary as the senior civil servant. Standards throughout the service would be maintained by the office of Inspector-General, although the latter was dropped from the Air Council on 6 February 1919 and the post was abolished on 1 April 1920, not to be reintroduced until 1 September 1937.

THE AIR COUNCIL, 11 NOVEMBER 1918 SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE ROYAL AIR FORCE

The Lord Weir of Eastwood PC

PARLIAMENTARY UNDER-SECRETARY OF STATE FOR AIR

Major J.L. Baird CMG, DSO, MP

PERMANENT UNDER-SECRETARY OF STATE FOR AIR

W.A. Robinson Esq. CB, CBE

CHIEF OF THE AIR STAFF

Major-General F.H. Sykes CMG

MASTER-GENERAL OF PERSONNEL

(Later entitled Air Member for Personnel) Major-General W.S. Brancker AFC

CONTROLLER-GENERAL OF EQUIPMENT

(Later entitled Air Member for Supply and Organization) Major-General E.L. Ellington CMG

DIRECTOR-GENERAL OF AIRCRAFT PRODUCTION

(MINISTRY OF MUNITIONS)

Sir Arthur Duckham KCB

ADMINISTRATOR OF WORKS AND BUILDINGS

Sir John Hunter KBE

INSPECTOR-GENERAL OF THE ROYAL AIR FORCE

Major-General Sir Godfrey M. Paine KCB, MVO

(ex-RNAS officer)

Major-General Frederick H. Sykes CMG.

The Air Ministry

The Air Ministry was divided into departments concerned with different aspects of policy. The titles are mostly self-explanatory and go to show how complex a military organization is at staff level. Indeed many of these staff posts are replicated, albeit with a reduced scope of responsibility, at lower levels of command, in November 1918, areas and groups.

- Department of the Chief of Air Staff Coming directly under the Chief of the Air Staff, Major-General Sykes, were the staff officers responsible for the conduct of air operations, organization and air intelligence. This included the deployment of wings and squadrons between home and overseas commands and the acquisition of intelligence necessary for the prosecution of effective air operations, together with the organization necessary to give effect to them.

- Master-General of Personnel Major-General Brancker’s department was responsible for all aspects of personnel, such as promotions and postings to ensure that stations and squadrons were manned to meet operational and training tasks to agreed establishments. Training, so vital to ensure that personnel were fitted to take their place on operational units, came under this department. Finally the department administered the medical services of the RAF. Its head was later titled Air Member for Personnel.

- Controller-General of Equipment Major-General Ellington oversaw the provision of aircraft storage parks and repair depots. The Air Quartermaster’s department was responsible for the provision of aircraft spares and equipment, together with technical and domestic supplies and the supply depots that stocked them. Other sub-departments provided for Kite balloons, marine, wireless and photographic equipment. The head of this department was later titled Air Member for Supply and Organization.

- Director-General of Aircraft Production Sir Arthur Duckham was responsible for the procurement of aircraft by awarding aircraft contracts for prototypes and the production of approved designs for operational and training units.

- Administrator of Works and Buildings Sir John Hunter’s department oversaw works and buildings, including such items as airfield construction, airfield drainage, water, heating and work at marine establishments.

THE OPERATIONAL AND TRAINING COMMANDS AT HOME AND OVERSEAS, NOVEMBER 1918

The organizational charts and maps that follow show squadron deployments and therefore the Order of Battle on Armistice Day 1918, together with a brief description of the circumstances that brought the various squadrons to those locations. The roles of the squadrons – for example, fighter, bomber or anti-submarine – are shown on the theatre maps. The specifications of aircraft in service on Armistice Day, and those that were introduced into squadron service by the end of 1929, are shown in Appendix A. The locations of all operational units on Armistice Day, and their movements between the wars and at the outbreak of hostilities in 1939, are in Appendix B.

Home Commands

Transition from Admiralty/War Office to Air Ministry Organization

On 1 April 1918 the command structures for the RAF were those that had been passed on by the older services, the Royal Naval Air Service and the Royal Flying Corps. The flying units of the RNAS came under the command of naval flag officers for fleets at sea, e.g. Flag Officer Grand Fleet, for ship- or carrier-borne aircraft, and home port establishments, e.g. Plymouth, Devonport, Chatham or Rosythe, for shore-based squadrons. Those of the RFC were organized into training divisions, both operational and training, broken down further into brigades, wings and squadrons. In order to avoid confusion with Navy and Army command structures it was decided at a meeting of the Air Council on 19 February 1918 to use Areas, numbered 1 to 6, rather than Commands, used by both the older services, or Divisions, used by the Army. The areas were subdivided into Groups, which would not clash with either of the two sister services, and being indeterminate in size, they allowed the RAF to decide in time how many wings and squadrons should make up a group. This in turn gave rise to an interesting anomaly when the new RAF ranks were introduced in 1919. Initially group captains did command groups, wing commanders wings and squadron leaders squadrons. Often, if a force was set up for a particular operation, a group captain could well command. The Indian Group on the North-West Frontier was commanded by a group captain. But these were the days before RAF stations were the established norm. Wings and squadrons could well be situated on an airfield that also housed other minor units, and a squadron might be commanded by a wing commander who doubled up as OC squadron and OC minor units, as at Kohat and Basra, for example. Later, RAF stations became the norm, and squadrons or wings could come and go, but the piece of real estate that was the RAF station stayed put. It was therefore necessary to appoint group captains to be the commanding officers of stations superior in rank to the commanders of wings and squadrons that had taken up residence on a station. A number of stations would then comprise a group, which had to be commanded by an officer of superior rank to a group captain. Strangely enough, this was not to be an air commodore but an air vice-marshal. The air commodore was mostly found on the headquarters staff or as the commanding officer of a station with group status, such as Halton and Cranwell.

Later, large RAF stations, particularly flying stations, commanded by a group captain, had three wing commanders under command. These would be the Wing Commander Flying, who had the operational squadrons, the Wing Commander Technical, who presided over the engineering, armament, signals, safety equipment, photographic and motor transport sections, and finally the Wing Commander Administrative, who looked after equipment, accounts, personnel, married quarters, padres and other miscellaneous sections.

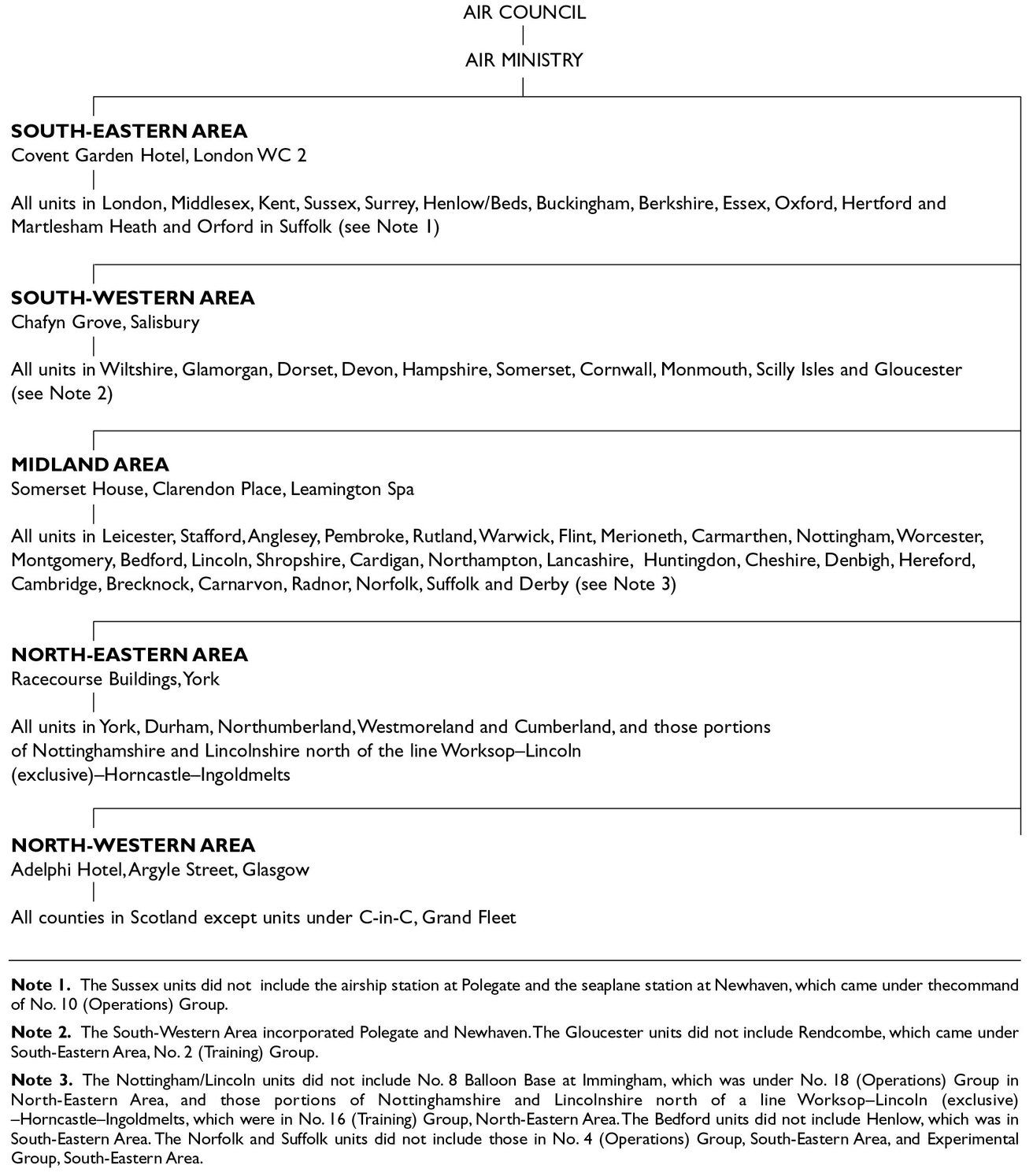

The numbering of areas did not last long, and on 8 May 1918 the numbered areas became geographical areas. These are shown below, with reference notes following. The RAF Commands introduced in the 1930s were functionally organized, e.g. Fighter, Bomber, Coastal, Training, but the RAF Areas of 1918 were multifunctional. Thus Major-General F.C. Heath-Caldwell CB, based at the Covent Garden Hotel, London, commanded all units in the south-eastern counties. These included Home Defence fighter squadrons based at such stations as Detling and Biggin Hill, as well as the anti-submarine squadron based at Dover and the maritime reconnaissance squadron based at Manston. But some units for logistical or organizational reasons did not come under the command of the General Officer Commanding of their areas. So Newhaven, the home of No. 242 Squadron, with its Short 184s, DH6s and Campanias employed on anti-submarine duties, was part of No. 10 (Operations ) Group, which came under the command of Major-General M.E.F. Kerr CB, MVO, based in Salisbury, commander of South-Western Area. These areas were to undergo several modifications in the years that followed, mainly to reflect the peacetime organization of the forces, bearing in mind that the RAF was to designate aircraft for cooperation with the Army and to man, alongside naval airmen, carrier-borne aircraft of the various fleets. All the shore-based squadrons that used to belong to the RNAS had a 200 prefix, so that No. 1 Squadron became No. 201 Squadron.

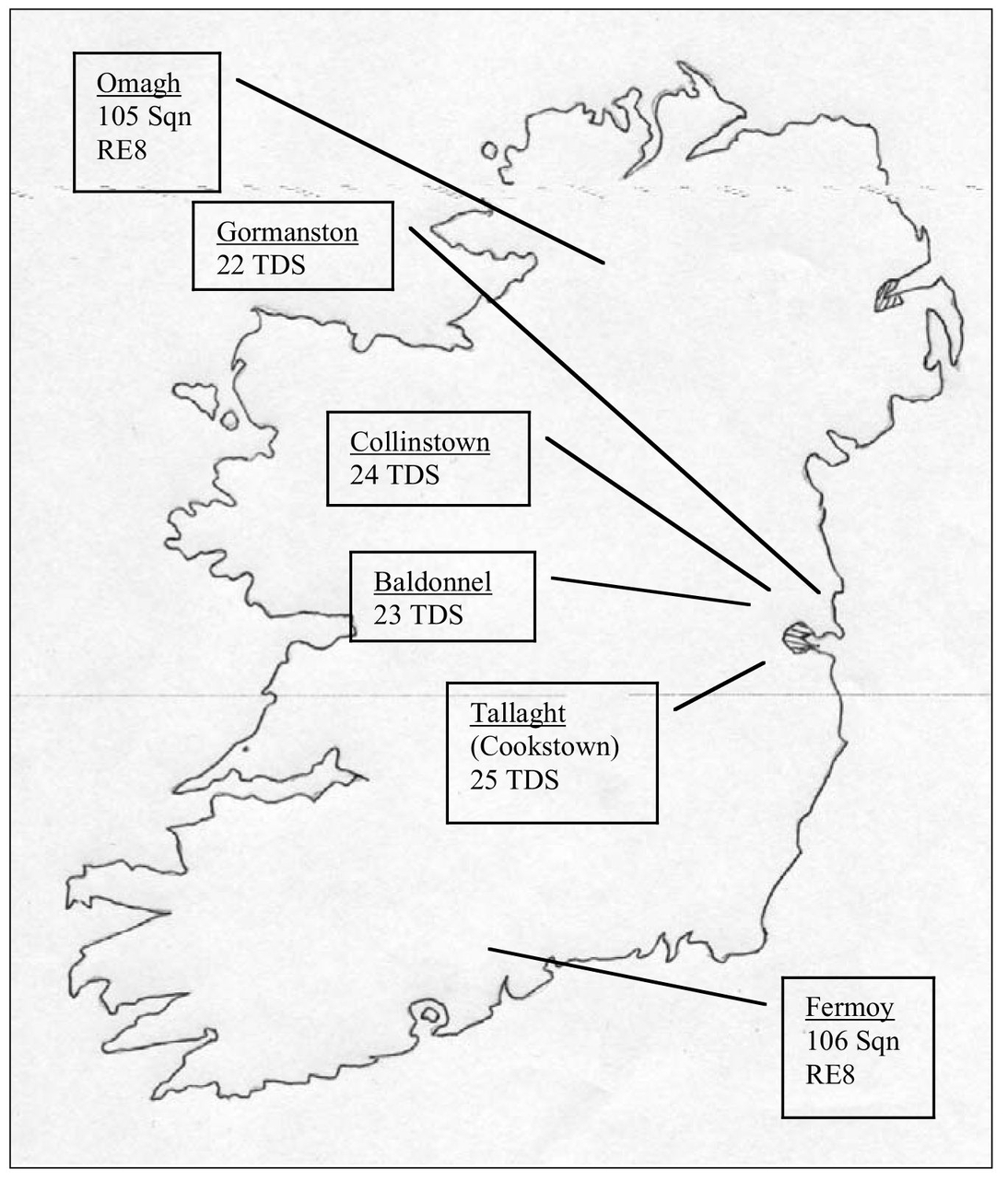

The sixth geographical area, which was unnumbered, was the Irish Area. Since all thirty-two counties of Ireland came under the Crown, RAF squadrons were based in what is now Ulster, as well as in the southern counties. This area or command later took on group status, becoming No. 11 (Irish) Group.

ORDER OF BATTLE, UK AREAS, 11 NOVEMBER 1918

Finally, references to General Officers Commanding of RAF areas persisted until the new RAF titles were introduced on 27 August 1919, when GOC became AOC, or Air Officer Commanding, the term air officer referring to officers of the highest rank, from Air Commodore to Marshal of the Royal Air Force. It must be borne in mind that the order of battle for units at home and overseas as depicted in this chapter had to undergo major changes following the rapid rundown from 188 operational squadrons to fewer than thirty. That is why this chapter concentrates on the circumstances that brought the units to the airfields, landing grounds and RAF stations of November 1918. Most of the stations were relinquished, only to be resurrected in the 1930s with the expansion programmes.

Units under Command, Geographical Areas in November 1918

These were as follows:

- Air defence squadrons

- Bomber/torpedo squadrons

- Maritime reconnaissance squadrons

- Squadrons aiding the civil power in Ireland

Air-Defence Squadrons

The deployment of air-defence squadrons on Armistice Day 1918 was not dissimilar to the deployment of squadrons of fighter command in 1940, but with three major differences. Firstly, the range of enemy aircraft was not as great as it is today, and since German bomber units could get no closer to Britain than their airfields in Belgium there was no threat of attack to the south-west of England, the west Midlands, Wales, the north-west and Scotland. Admittedly the Zeppelins had the range and had penetrated UK air defences on a number of occasions in the First World War, but airships were vulnerable, being slow and presenting far too large a target to fighters. By 1917 the threat of Zeppelin attacks had receded and was superseded by raids from Gotha bombers, which had to be fitted with extra fuel tanks to give them the range to reach London with a margin for bad weather or dispersion should formations be attacked.

Secondly, the bomb load was not as great as it was in 1940, nor was the sophistication of bombsights. Although 1,000 lb and 500 lb bombs were common in the Second World War, a typical bomb load of an entire formation of Gothas dropped on London in 1917, for example on Friday 25 May, was 163 bombs weighing 4,550 lb in total. This was from twenty-one aircraft that crossed the coast, out of twenty-three that set out from Belgium. And that raid did not cause the greatest monetary loss to Britain, being £19,405, compared with £205,622 lost on Saturday 7 July, when only 3,149 lb were dropped, i.e. luck played a major part.

Thirdly, in the First World War there was no radar-controlled fighter defence system, with sector operations rooms directing fighters to attack incoming enemy bombers, as there was in 1940. When the Gotha raids began in 1917 the air defences were so uncoordinated that the Gothas could bomb almost with impunity. They would have London as the primary target, but secondary targets were planned in case of bad weather or diversion because of fighter interception. When Folkestone came under heavy attack there was great pressure from the civilian population to provide adequate air defence. Three things had to happen in 1917. Firstly, the combined defences of the capital had to be brought under one command, that is heavy ack-ack batteries, as well as defending fighters of the RFC and RNAS. Secondly, there had to be an effective means of giving air raid warnings. And thirdly there was a dire need for modern fighter aircraft that had the rate of climb and speed to catch the enemy. This meant diverting aircraft from the Western Front and also stopping the wrangling between the Army and the Navy over the acquisition of aircraft from the factories. This wrangling ceased when the RFC and the RNAS were merged into the RAF the following year.

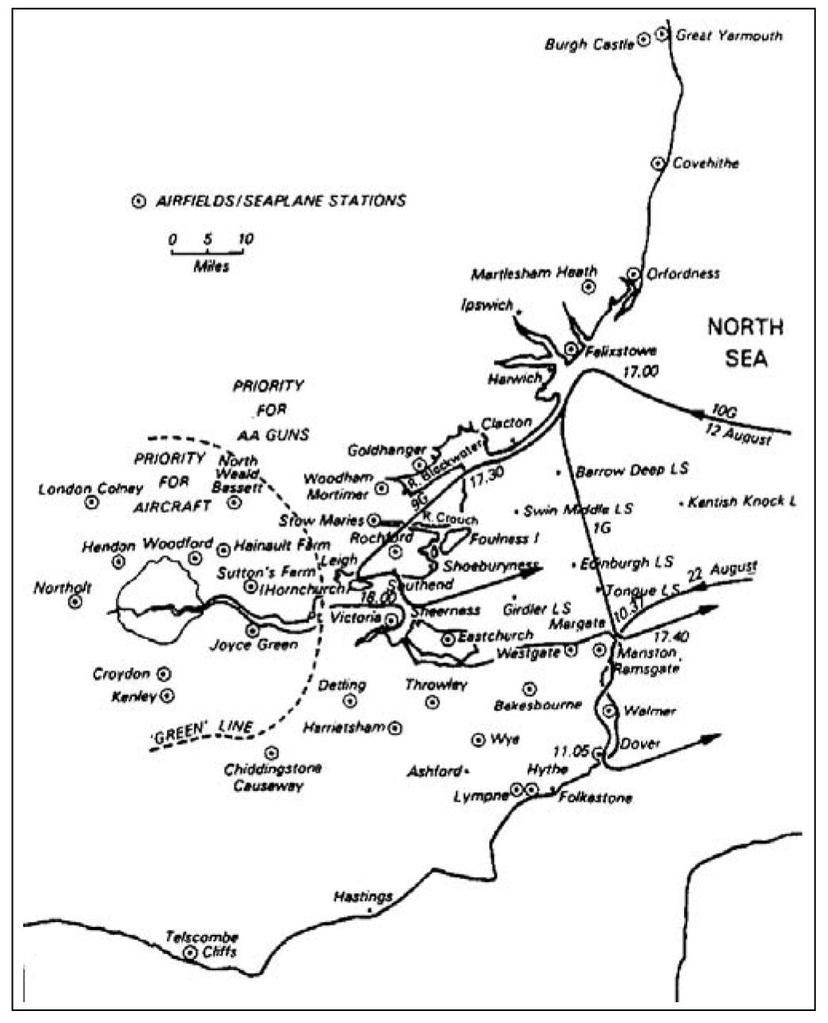

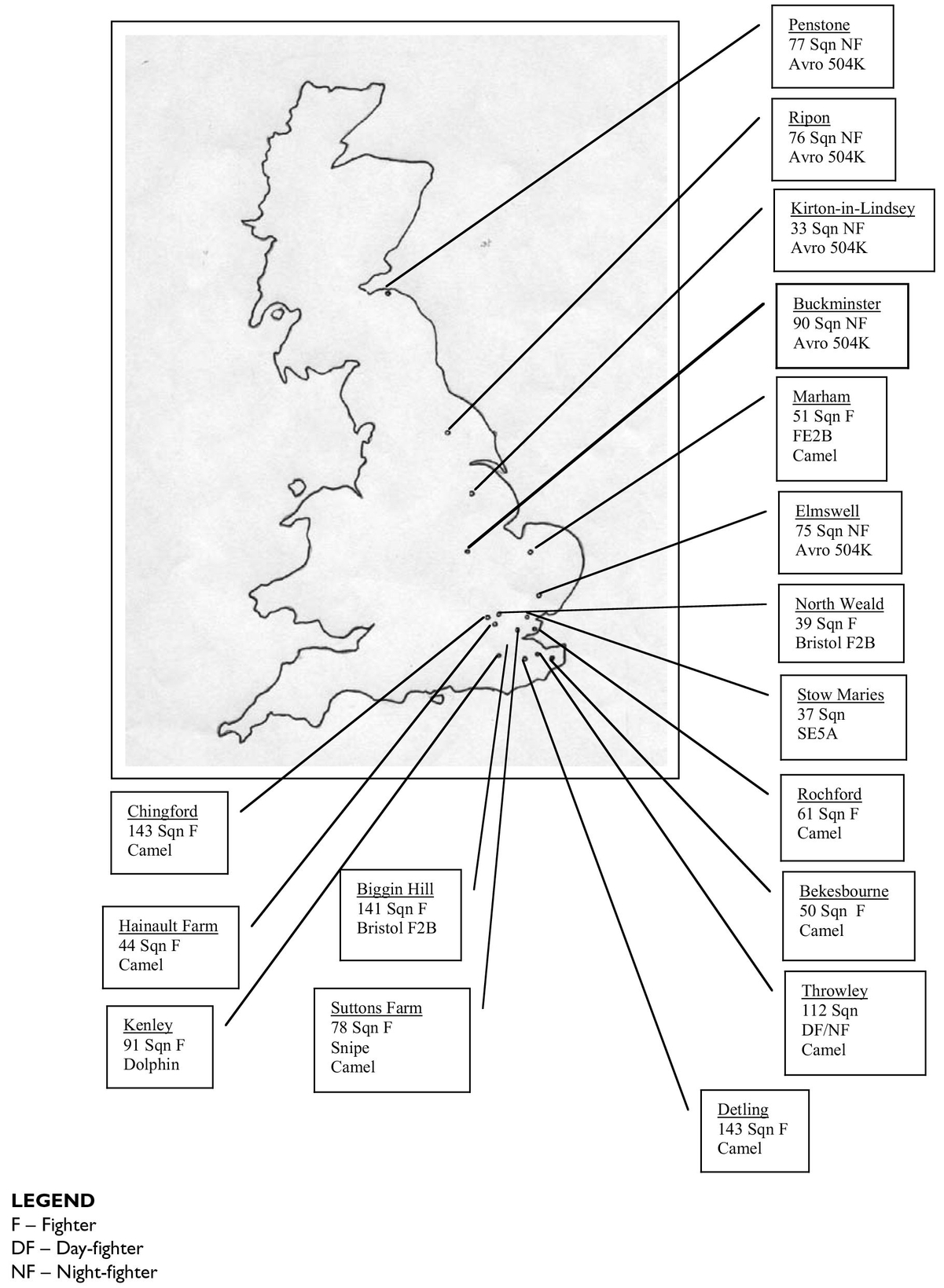

The map shows that the faster, more agile aircraft, e.g. Camels, Snipes and SE5As, were situated round the capital. The slower Avro 504Ks were relegated to the more northerly stations, which only the Zeppelins could reach. A typical Gotha attack pattern, which explains the positioning of fighter units, is shown below.

AIR DEFENCE SQUADRONS BASED IN THE UNITED KINGDOM 11th NOVEMBER 1918

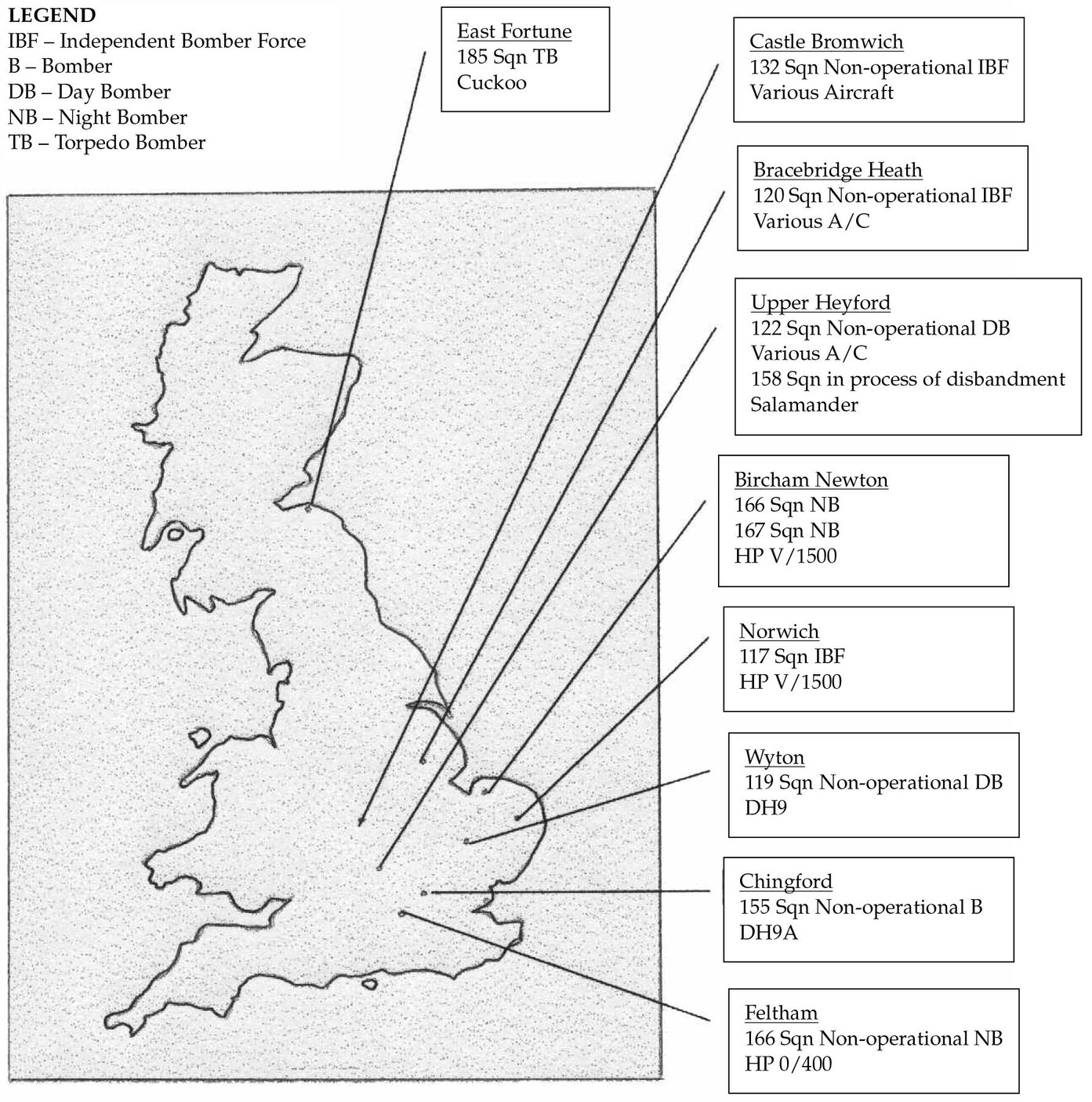

Bomber/Torpedo-Bomber Squadrons

A close inspection of the map on the next page shows that there were virtually no operational bomber units on the British mainland in November 1918. The reason for this is simple. Almost the entire strategic bomber force, 8 Brigade, was in France, commanded at the cessation of hostilities by Major-General Trenchard. Those units that were in the UK were working up to operational readiness in November 1918, and a few units were actually in the act of disbanding. These were squadrons with the DH9, 9A or Salamanders, all aircraft that would need to be much closer to the enemy to be effective. The only units of significance in this context were the squadrons equipped with the HP 0/400 and HP V/1500 aircraft, which could operate from the United Kingdom. In the case of the HP V/1500, bombing attacks from the UK base on Berlin were planned, and No. 117 Squadron, based at Norwich, was part of the Independent Bomber Force (IBF). Nos 166 and 167 Squadrons at Bircham Newton were designated night-bomber squadrons.

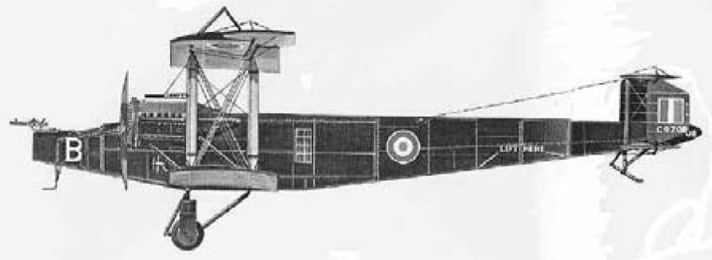

HP 0/100.

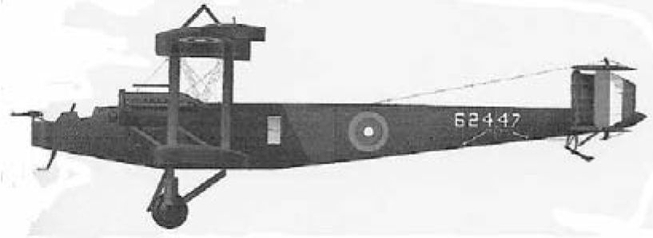

HP 0/400.

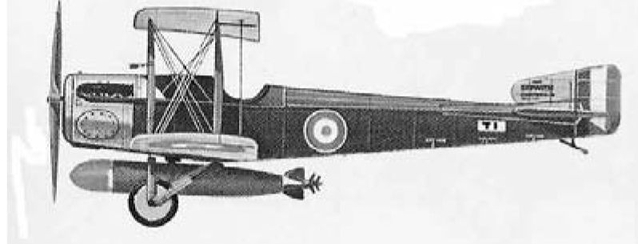

HP V/1500.

Sopwith Cuckoo.

RAF First World War bombers It was to be the Royal Navy that first entered into strategic bombing, just as it is the Navy today that deploys the strategic deterrent. It was the Admiralty in 1914 that asked the aircraft industry for a ‘bloody paralyser’ for the bombing of Germany. This was to be the Handley Page 0/100, which went into service with the RNAS in November 1916 and bombed U-boat bases, railway stations and industrial centres. Its successor was the HP 0/400, of which nearly 800 were ordered during the war and approximately 550 were built in the UK. There were 258 HP 0/400s on charge to the RAF at the Armistice, and they could carry a bomb up to 1,650 lb in weight. It was used as a day- and night-bomber by both the RFC and the RAF in the IBF. This type remained in RAF service until 1920. The HP V/1500 was too late for the First World War and was of no use in the ‘whittled-down’ peacetime RAF. Since it did go into production and did equip three RAF squadrons in the UK, the V/1500 does have a place in history. It was the first four-engined bomber in service and was the largest aircraft built by a British aircraft company in the First World War. The Air Ministry required an aircraft that had a combat radius of 600 miles, i.e. so that it could bomb Berlin from Bircham Newton. The first prototype flew in May 1918, powered by two tandem pairs of 375 hp Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII engines.

Anti-shipping The only anti-shipping unit was No. 185 Squadron based in East Fortune, Scotland. Armed with torpedoes, the Sopwith Cuckoos could attack surface craft in the North Sea. The Cuckoo was not delivered until July 1918, and met the need for a single-seater, land-based aircraft carrying one or two 1,000 lb torpedoes and having an endurance of four hours. A total of 350 Cuckoos were ordered, but contracts were curtailed with the coming of the Armistice, and in the event only 150 were built.

Maritime Reconnaissance and Anti-Submarine Squadrons

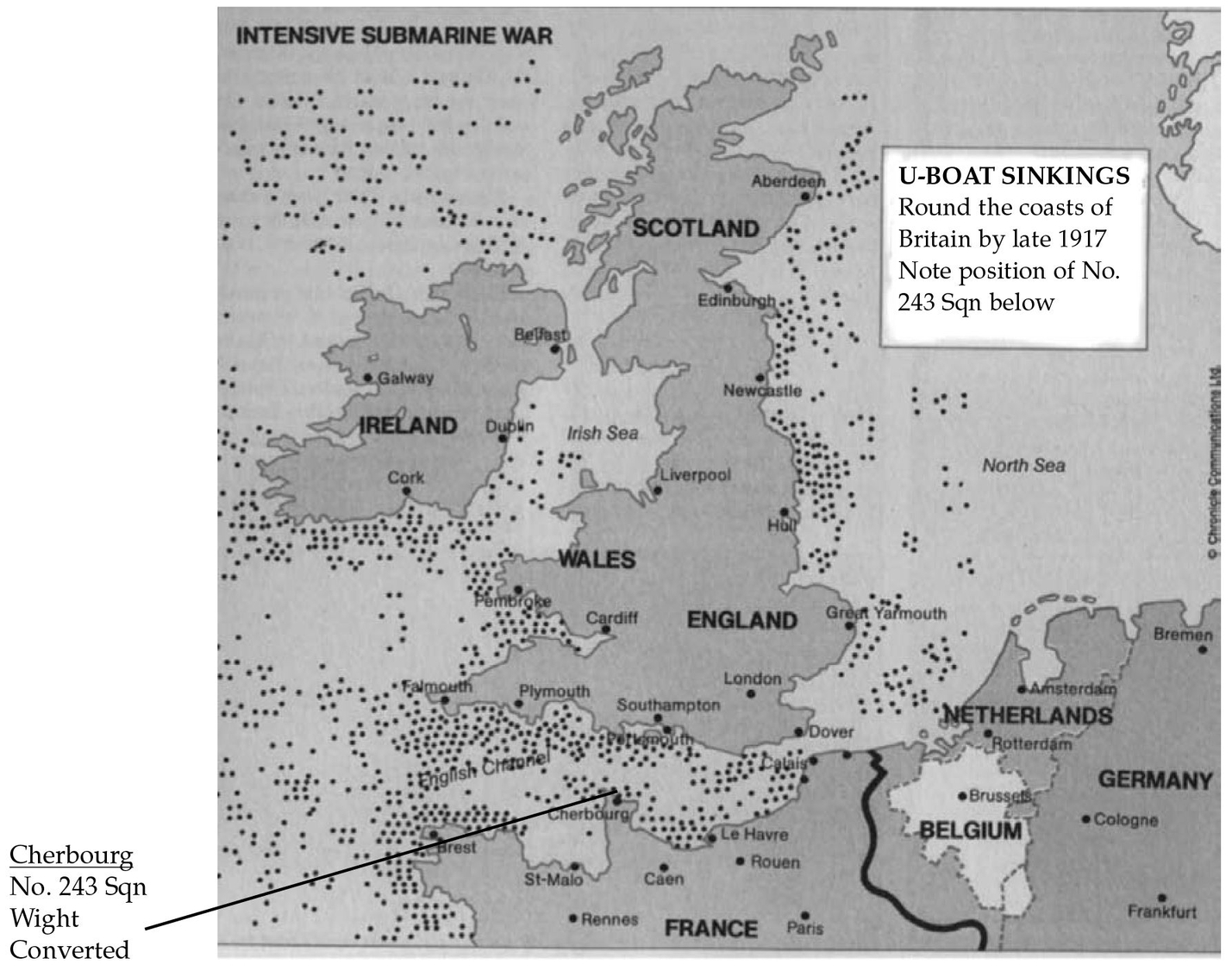

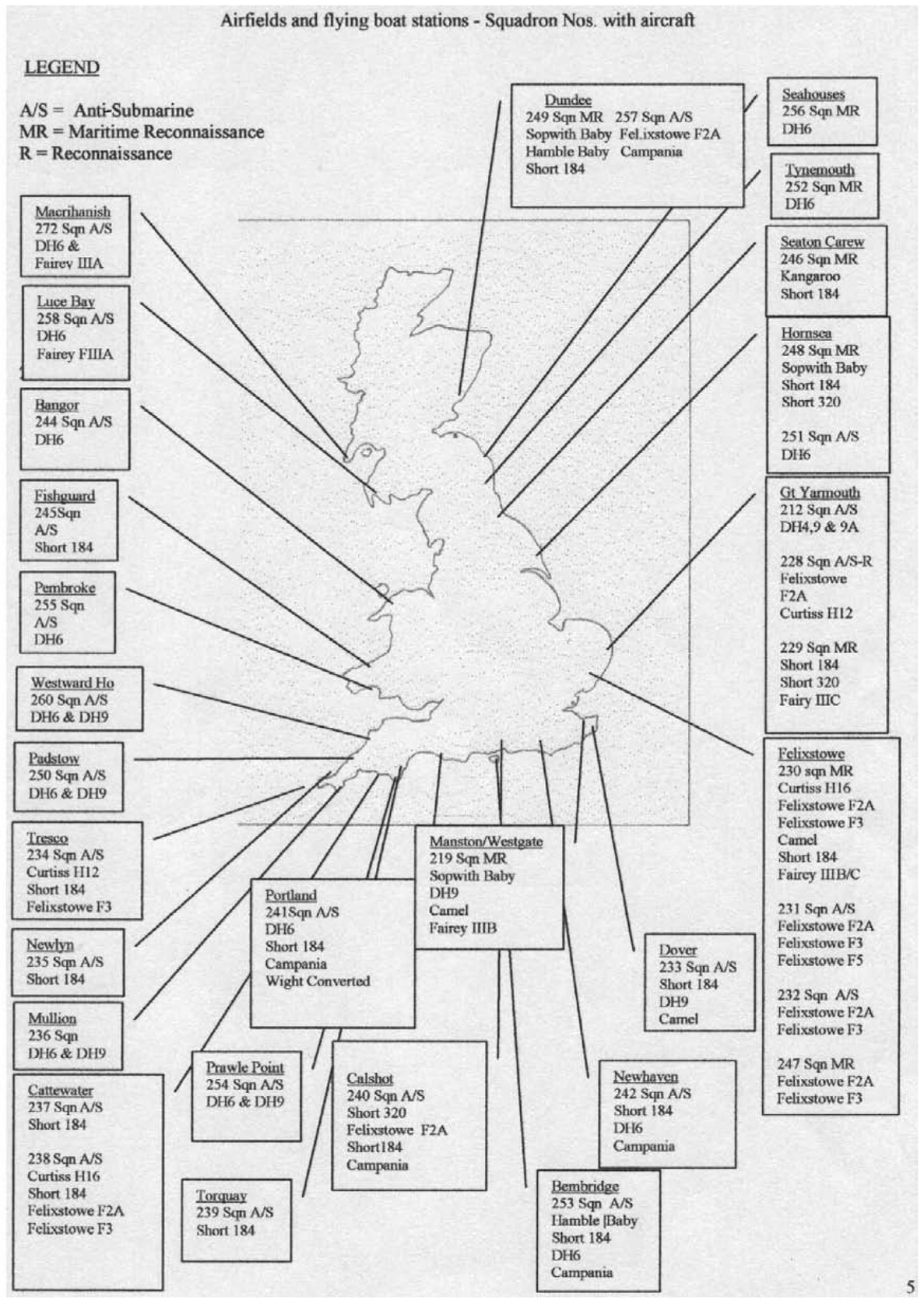

The map on page 12 shows the disposition of maritime reconnaissance and anti-submarine squadrons. Seaplane stations abounded to cover not only the English Channel but also the Western Approaches for sea traffic coming into the Bristol Channel, as well as the Irish Sea approaches to Liverpool and the approaches to the Clyde. The units in eastern and north-eastern England patrolled the North Sea. When one considers that today there is just one maritime reconnaissance and strike base in the UK, at Kinloss, to cover all approaches to the United Kingdom, together with flights of No. 22 Squadron dispersed at various stations around our shores for air-sea rescue, it is a far cry from the twenty-six airfields and flying-boat stations of 1918. The range and speed of these relatively fragile machines meant providing dense coverage of the sea areas around the United Kingdom to ensure interception of submarines. The same would apply to reconnaissance if the approach of hostile vessels was to be known.

OPERATIONAL AND NON OPERATIONAL BOMBER UNITS AND TORPEDO UNIT BOMBER UNITS – 11 NOVEMBER 1918

A number of squadrons, notably No. 230 Squadron, were equipped with a variety of aircraft, but this does not seem to have posed a maintenance problem. Of interest is the equipment of No. 241 Squadron at Portland, which had the handful of Wight Converted seaplanes bought by the Admiralty from J. Samuel Wight & Co., East Cowes, Isle of Wight. Another rare aircraft, the Kangaroo, equipped just No. 246 Squadron at Seaton Carew. These were sold after the war to be used for commercial flights. The Felixstowe family of flying-boats made at Felixstowe not unsurprisingly equipped all of the four squadrons based there. With regard to maritime operations at the close of hostilities in November 1918, the patrol of the waters off the coasts of the British Isles remained a high priority. The RNAS had started to do this in September 1914, and by the time of the declaration of the Armistice the RAF maritime squadrons were employed on searching for enemy submarines, escorting convoys, assisting surface vessels to hunt down enemy submarines and locating and destroying mines laid by the enemy off the coasts of Britain, particularly in the entrance to the major ports. By July 1918 no fewer than thirty balloons were being taken to sea by the Grand Fleet on all occasions. They aided materially in the anti-submarine campaign, and were towed from drifters, trawlers and motor launches in large numbers for reconnaissance purposes.

FOUR AIRCRAFT TYPICAL OF THOSE USED IN MARITIME OPERATIONS IN 1918

DH9.

Sopwith Baby.

Felixstowe F2A.

Short 184.

The map below graphically illustrates the necessity for the dense anti-submarine defence capability and the formation of No. 10 (Operations) Group RAF.

MARITIME RECONNAISSANCE/ANTI-SUBMARINE SQUADRONS BASED IN THE UNITED KINGDOM – 11 NOVEMBER 1918

Air defence of the English Channel grew from a single seaplane station at Calshot when, in early 1915, Bembridge on the Isle of Wight was added. When U-boat sinkings rose in 1916, Portland was opened as a seaplane base, and when cross-Channel traffic of men and supplies in and out of Newhaven attracted the attention of U-boat commanders, that station also was added. To cover the northern half of the Channel was an airship base at Polegate, and when it was seen that there was insufficient capacity to provide adequate maritime reconnaissance, two mooring-out stations were added. Protection of shipping in the southern half of the Channel was catered for by the establishment of a seaplane base at Cherbourg, where traffic had increased. To coordinate the air defences of this vital sea area it was decided to establish No. 10 (Operations) Group with a senior air officer and staff situated at Warsash. Seaplane training was moved from the operational base at Calshot to a training establishment at Lee-on-Solent.

RAF Squadrons and training establishments in Ireland

The map on Page 14 is different from the others in that it shows training establishments in Ireland. Far away from the fighting in Flanders, there were four training depot stations there, and flying training could safely take place. Additionally there were two operational squadrons and an attached flight from the mainland.

Operational duties

In April 1918 the military situation in France caused the British government to extend conscription into the armed forces to Ireland. This was deeply unpopular, added to which the matter of Irish Home Rule still remained unresolved. Fearful that trouble might be caused by Irish Republicans, the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, Field Marshal Viscount French, drew up plans to police Ireland using airpower. He told the Prime Minister, Lloyd George, of his plans to establish strongly defended air camps from which aircraft could patrol with bombs and machine-guns.

Accordingly two squadrons were dispatched in May 1918 – No. 105 Squadron to Omagh and No. 106 Squadron to Fermoy. Both units had been formed at Andover in September 1917. Flying RE8s, they were both corps reconnaissance units, and that is what they remained, i.e. they were not used in an offensive role, in spite of French’s original intent. These aircraft also proved useful in a communications role. A pilot joining No. 106 Squadron told of his approach to Fermoy in County Cork. He had been led to believe that the airfield was a racecourse just on the outskirts of town. He was shocked to find that the airfield was surrounded with barbed-wire entanglements and sand-bagged gun emplacements, almost as if it was on the front line in France.

The approach to the mooring – Malahide Castle, Ireland.

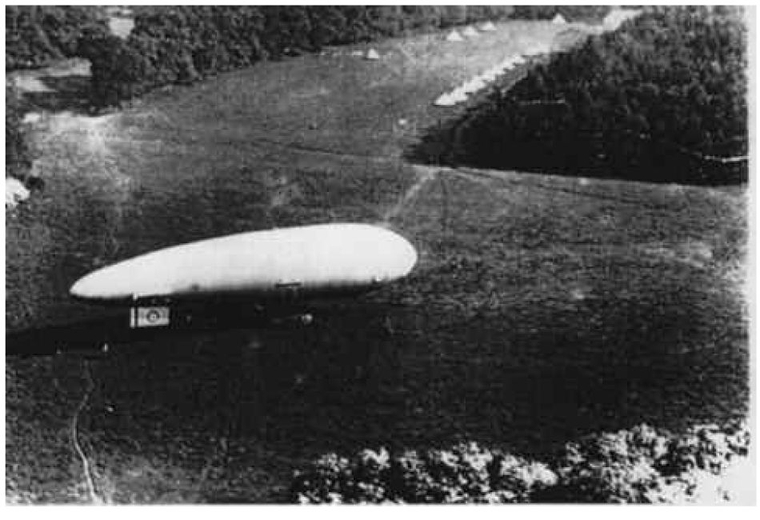

Anti-submarine duties were also important. To cover the Irish Sea were units at Fishguard, Pembroke and Bangor. No. 244 Squadron, equipped with DH6 aircraft at Bangor, detached a flight to Tallaght, south-west of Dublin, to cover the sea approaches to that port. When the United States of America came into the war in 1917, it sent not only airships to augment those operated by the RNAS in the fight against the U-boat, but battleships in case the enemy should decide to use surface forces against Allied convoys and coastal shipping. The vital importance of anti-submarine forces was brought home to all concerned when the Royal Mail Steamer Leinster was sunk en route from Kingstown to Holyhead on 10 October 1918. More than 500 persons were either killed or injured. The day before the sinking, the airship that should have been covering the sea approaches to Kingstown was caught in the trees and wrecked as it approached its mooring at Malahide Castle, near Dublin. Five RAF passengers were buried in the military cemetery beside the Phoenix Park in Dublin.

Flying Training in Ireland

On 6 July 1918 plans were finalized to establish four training depot stations in Ireland. No. 22 TDS Gormanston, Co. Meath, was to become operational on 4 October, No. 23 TDS Baldonnel, Co. Dublin, on 9 October, and No 24 TDS Collinstown, Co. Dublin, and 25 TDS Cookstown, Co. Dublin, on 25 October. But the Armistice intervened before these stations could make any real contribution to the war effort. The main period of training activity at the four Irish TDSs was brief, lasting only from August until December. The plan was then to move the training units back to the mainland, but the rapid rundown in 1919 saw most training units disbanded. It is interesting to recite that American service personnel were posted to the TDSs to repair US naval aircraft.

RAF SQUADRONS AND TRAINING ESTABLISHMENTS IN IRELAND, NOVEMBER 1918

RAF Strength in Ireland

RAF operational and training aircraft, together with the US Curtiss flying-boats, numbered more than 300 at the Armistice. There were 184 Avro 504s and 41 DH9s, together with the RE8s of the two squadrons at Omagh and Fermoy.

ORDER OF BATTLE: RAF IN THE FIELD, 11 NOVEMBER 1918

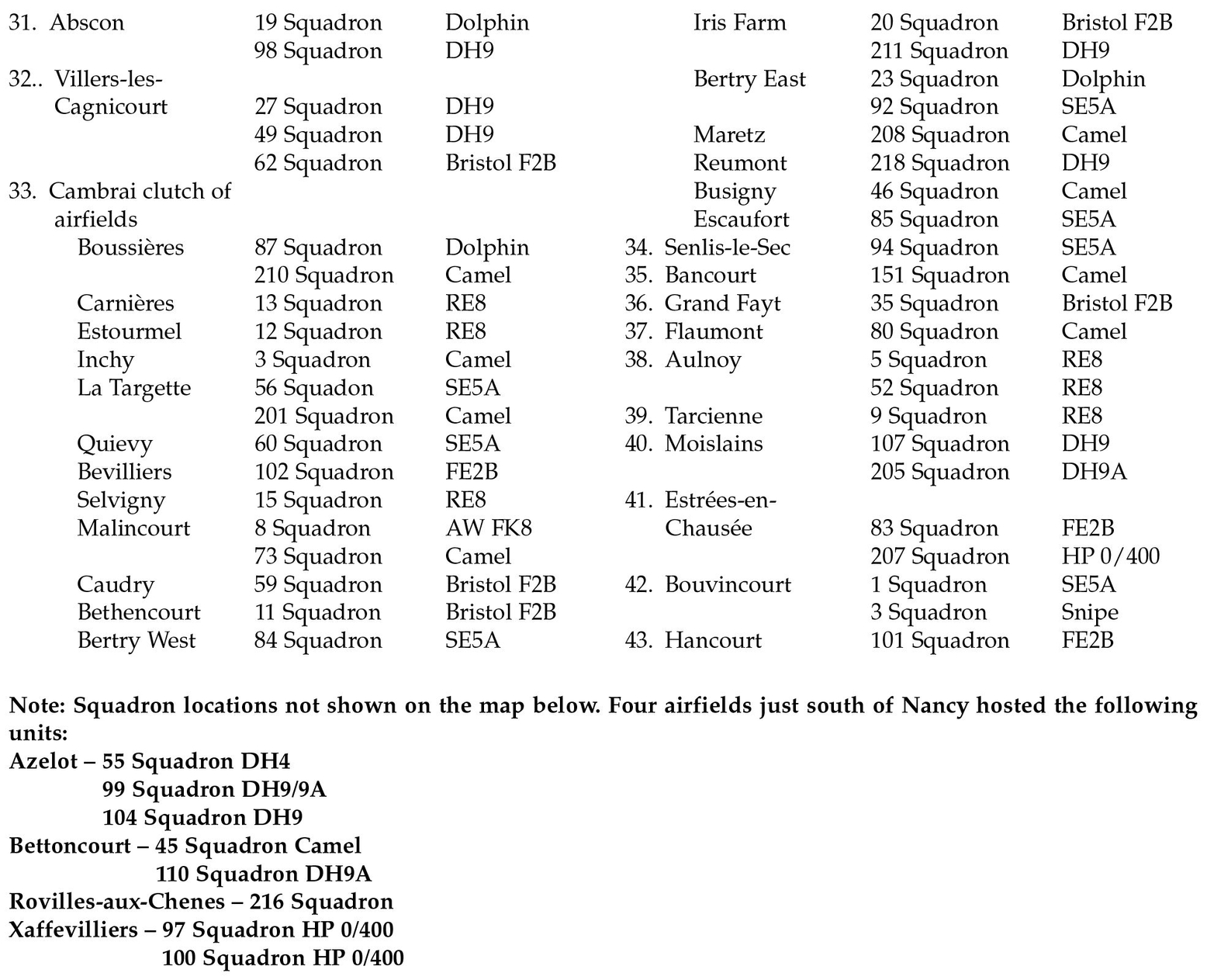

RAF in France and Belgium

The Final Allied Offensive The final offensive began on 8 August with the Battle of Amiens, and by 27 September the notorious Hindenburg Line was being assaulted. The RAF had 800 aircraft to support the armies, together with some 1,100 French aircraft. Confronting them were only 365 German aircraft, of which forty were fighters. Although 23,000 German prisoners had been taken, the enemy put up a tenacious defence, as the Americans found out. More than a thousand aircraft supported the attack on the enemy-held line. Seven hundred tons of bombs were dropped and 26,000 machine-gun bullets fired from the air. The map overleaf shows the concentration of operational squadrons in the Cambrai area. By nightfall on the 27th, a further 10,000 prisoners had been taken, together with two hundred guns, i.e. 33,000 prisoners in one day. Throughout October the offensive continued, and by 18 October the Belgian Army had reached Bruges and Zeebrugge and the British were holding a line along the River Lys. As they went the Germans carried out delaying demolitions. The warfare, which had been stuck in the trenches for well-nigh four years, was now fluid, and the cavalry could at last come into its own. By 1 November, the British forces had reached the Scheldt and the Oise, and Valenciennes was captured. German prisoners were now being taken in their thousands, and on 9 November British troops crossed the Scheldt. Two days later the Armistice was signed.

Fighter/Bomber Tactics in late 1918 As the war neared its end, the RAF had the strength and superiority that permitted the use of formations in wing strength. 10 Brigade’s No. 80 Wing, for example, was operating fighter sweeps in layers. The Snipes of No. 4 Australian Squadron would form a top layer at 7,000 – 8,000 ft. Lower down would be the Bristol Fighters of No. 88 Squadron at 6,000 ft, the Camels of No. 46 Squadron at 4,000 ft, the SE5As of No. 2 Australian Squadron at 3,000 ft, and finally the DH9s of No. 103 Squadron would be at 2,000 ft. The DH9 bombers would have the immediate protection of the SE5As, which themselves had three layers of fighters above. This left the Germans with no choice but to attack only the top layer of fighters if they were not themselves to come under attack. No. 80 Wing operated between Ypres and Arras and could penetrate some fifteen to twenty miles into enemy territory. While the German fighters were not destroyed in the air, they were driven from the skies. The wing therefore attacked the enemy’s airfields, and the Germans risked either losing their aircraft on the ground or taking to the air to be engaged by the British forces. Indeed, during the last year of the war a great number of dogfights took place, the last major one taking place on the morning of 4 November. The Germans may have been outnumbered, but they were defeated not so much in the air as through the lack of fuel.

The Independent Bomber Force This comprised squadrons of 8 Brigade and units based in East Anglia. The squadrons of 8 Brigade were equipped with DH4s and DH9s of No. 41 Wing at Azelot, the Camels and DH9As of No. 88 Wing at Bettoncourt and the HP 0/400s of No. 83 Wing at St Inglevert, Xaffevillers in Belgium and Rovilles-aux-Chenes. In May 1918 the government decided that 8 Brigade had proved so successful in attacking targets divorced from the battlefield that it should be expanded into an Independent Bombing Force, the first of its kind to operate entirely independently of the Army. Its commander was Trenchard, who had resigned from the post of Chief of the Air Staff following a disagreement with Lord Rothermere. Trenchard’s command of 8 Brigade taught him the importance of the bomber offensive. Its primary targets would be German munitions factories, poison-gas plants, and aeroplane and aero-engine factories, with secondary targets in railways and blast furnaces if the primary targets could not be reached. The Camels of the IBF were there to provide fighter protection to the day-bombers, for the Germans were determined to stop the onslaught. But even when a formation lost most of its bombers other bombers would return to the same target. In addition, single aircraft of the force carried out photoreconnaissance missions at great height. In this way the most economical use was made of the bomber effort. Altogether 550 tons of bombs were dropped in five months, 160 tons by day and 390 tons by night. Of the total, 220 tons were dropped on enemy aerodromes. As for attacks on British aerodromes, not a single aircraft was destroyed by enemy bombing during the lifetime of the IBF. The Handley Page V/1500s of the IBF were intended to bomb Berlin directly from their bases in the UK, but the Armistice intervened.

Deployments in France and Belgium The following pages list the units of the RAF in Brigades, Wings and Squadrons. These are shown in Appendix B as at their locations on 11 November 1918. It should be remembered, however, that the war was very fluid by this time, and unit locations would be changing to meet the needs of Army formations. The map on Page 16 only shows RAF squadrons. There were French and American units also taking part in the air offensive.

DEPLOYMENT OF RAF WINGS/SQUADRONS IN FRANCE AND BELGIUM, 11 NOVEMBER 1918

BRIGADES, WINGS, SQUADRONS AND MISCELLANEOUS UNITS

RAF in France and Belgium

HQ RAF

HQ Communications Squadron

No. 1 Aircraft Depot (includes No. 1 Port Depot)

No. 1 Aircraft Depot (D)

No. 1 Aircraft Depot (M)

No. 1 Aeroplane Supply Depot

No. 2 Aircraft Depot (includes No. 1 Port Depot)

No. 2 Aeroplane Supply Depot

Engine Repair Shops

British Aeronautical Supplies Depot

9 BRIGADE RAF attached to GHQ

No. 9 Wing comprising:

No.18 Sqn – DH9A (La Brayelle)

No.25 Sqn – DH9A (La Brayelle)

No.27 Sqn – DH 9 (Villers-les-Cagnicourt)

No.32 Sqn – SE5A (La Brayelle)

No.49 Sqn – DH9 (Villers-les-Cagnicourt)

No.62 Sqn – Bristol F2B (Villers-les-Cagnicourt)

No. 51 Wing comprising:

No. 1 Sqn – SE5A (Bouvincourt)

No. 43 Sqn – Snipe (Bouvincourt)

No. 94 Sqn – SE5A (Senlis le Sec)

No. 107 Sqn – DH9 (Moislains)

No. 205 Sqn – DH9A (Moislains

9th Aircraft Park

5th Air Ammunition Column

9th Air Ammunition Column

6th Reserve Lorry Park

20th Reserve Lorry Park

1 BRIGADE RAF attached to 1st Army

No. 1 Wing comprising:

No. 5 Sqn – RE8 (Aulnoy)

No. 16 Sqn – RE8 (Auchey)

No. 52 Sqn – RE8 (Aulnoy)

L Flight

1st Balloon Wing

4, 10 & 12 Balloon Companies

1st Aircraft Park

1st Air Ammunition Park

10th Wing comprising:

No. 19 Sqn – Dolphin (Abscon)

No. 22 Sqn – Bristol F2B (Aniche)

No. 40 Sqn – SE5A (Aniche)

No. 64 Sqn – SE5A (Aniche)

No. 98 Sqn – DH9 (Abscon)

No. 148 Sqn – FE2B (Erre)

No. 203 Sqn – Camel (Bruille)

No. 209 Sqn – Camel (Bruille)

I Flight

1st Reserve Lorry Park

11th Reserve Lorry Park

2 BRIGADE RAF attached to 2nd Army

No. 2 Wing comprising:

No. 4 Sqn – RE8 (Linselles)

No. 7 Sqn – RE8 (Menin)

No. 10 Sqn – AW FK8 (Staceghem)

No. 53 Sqn – RE8 (Sweveghem)

No. 82 Sqn – AW FK8 (Menin)

M Flight

No. 11 Wing comprising:

No. 29 Sqn – SE5A ( Marcke)

No. 41 Sqn – SE5A (Halluin)

No. 48 Sqn – Bristol F2B (Reckham)

No. 70 Sqn – Camel (Menin)

No. 74 Sqn – SE5A (Cuerne)

No. 79 Sqn – Dolphin (Reckham)

No. 149 Sqn – FE2B (Ste-Marguerite)

No. 206 Sqn – DH9 (Linselles)

2 BRIGADE RAF

2nd Balloon Wing

Nos 5, 6, 7, 8 & 17 Balloon Companies

2nd Reserve Lorry Park

7th Reserve Lorry park

No. 8 Salvage Section

2nd Air Ammunition Column

7th Air Ammunition Column

3 BRIGADE RAF attached to 3rd Army

12th Wing comprising:

No. 12 Sqn – RE8 (Estourmel)

No. 13 Sqn – RE8 (Carnieres)

No. 15 Sqn – RE8 (Selvigny)

No. 59 Sqn – Bristol F2B (Caudry)

N Flight

13th Wing comprising:

No. 56 Sqn – SE5A (La Targette)

No. 60 Sqn – SE5A (Quievy)

No. 87 Sqn – Dolphin (Boussières)

No. 210 Sqn – DH9 (Iris Farm)

No. 3 Balloon Wing

Nos 12, 16, 18 & 19 Balloon Companies

3rd Aircraft Park

3rd Air Ammunition Column

3rd Reserve Lorry Park

19th Reserve Lorry Park

No. 6 Salvage Section

No. 9 Salvage Section

5 BRIGADE RAF attached to 4th Army

No. 15 Wing

No. 6 Sqn – RE8 (Gondecourt)

No. 8 Sqn – AW FK8 (Malincourt)

No. 9 Sqn – RE8 (Tarcienne)

No. 35 Sqn – Bristol F2B (Grand Fayt)

No. 73 Sqn – Camel (Malincourt)

No. 3 Sqn (Australian Flying Corps)

No. 22 Wing

No. 24 Sqn – SE5A (to Bisseghem)

No. 46 Sqn – Camel (Busigny)

No. 80 Sqn – Camel (Flaumont)

No. 84 Sqn – SE5A (Bertry West)

No. 85 Sqn – SE5A (Phallempin)

No. 208 Sqn – Camel (Maretz)

No. 89 Wing comprising:

No. 20 Sqn – Bristol F2B (Iris Farm)

No. 23 Sqn – Dolphin (Bertry East)

No. 92 Sqn – SE5A (Bertry East)

No. 101 Sqn – FE2B (Hancourt)

No. 211 Sqn – DH9 (Iris Farm)

No. 218 Sqn – DH9 (Reumont)

No. 5 Balloon Wing

Nos. 13, 14 & 15 Balloon Companies

4th Aircraft Park

4th Aircraft Ammunition Depot

No. 7 Salvage Section

4th Reserve Lorry Park

12th Reserve Lorry Park

10 BRIGADE RAF attached to 5th Army

No. 80 Wing comprising:

No. 54 Sqn – Camel (Merchin)

No. 88 Sqn – Bristol F2B (Bersée)

No. 81 Wing comprising:

No. 2 Sqn – AW FK8 (Genech)

No. 21 Sqn – RE8 (Froidmont)

No. 103 Sqn – DH9 (Ronchin)

(Australian Flying Corps)

No. 2 Sqn – SE5A

No. 4 Sqn – Snipe

No. 42 Sqn – RE8 (Ascq)

P Flight

No. 8 Balloon Wing

Nos. 3, 11 and 20 Balloon Companies

10th Aircraft Park

10th Air Ammunition Column

9th Reserve Lorry Park

8 BRIGADE ( INDEPENDENT BOMBER FORCE)

41st Wing comprising:

No. 55 Sqn – DH4 (Azelot)

No. 99 Sqn – DH9 (Azelot)

No. 104 Sqn – DH9 (Azelot)

No. 83 Wing comprising:

No. 97 Sqn – HP 0/400 (Xaffevillers)

No. 100 Sqn – HP 0/400 (Xaffevillers)

No. 115 Sqn – HP 0400 (St Inglevert)

No. 215 Sqn – HP 0/400 (Xaffevillers)

No. 216 Sqn – HP 0/400 (Rovilles-aux-Chenes)

No. 88 Wing comprising:

No. 45 Sqn – Camel (Bettoncourt)

No. 110 Sqn – DH9A (Bettoncourt)

3rd Aircraft Depot

6th Aircraft Park

12th Aircraft Park

8th Air Ammunition Column

5th Reserve Lorry Park

10th Reserve Lorry Park

3rd Aeroplane Supply Depot

(Source document: National Archives, AIR/1/2129)

Aircraft Repair Depot near Rang-du-Fliers. Damaged aircraft were rebuilt at these depots and reissued to the mobile supply parks nearer the front line.

RAF padre takes a Sunday-morning service at No. 2 Aeroplane Supply Depot in 1918.

The pilot of an SE5A holding 85 Squadron’s score-board for 14 days in June 1918.

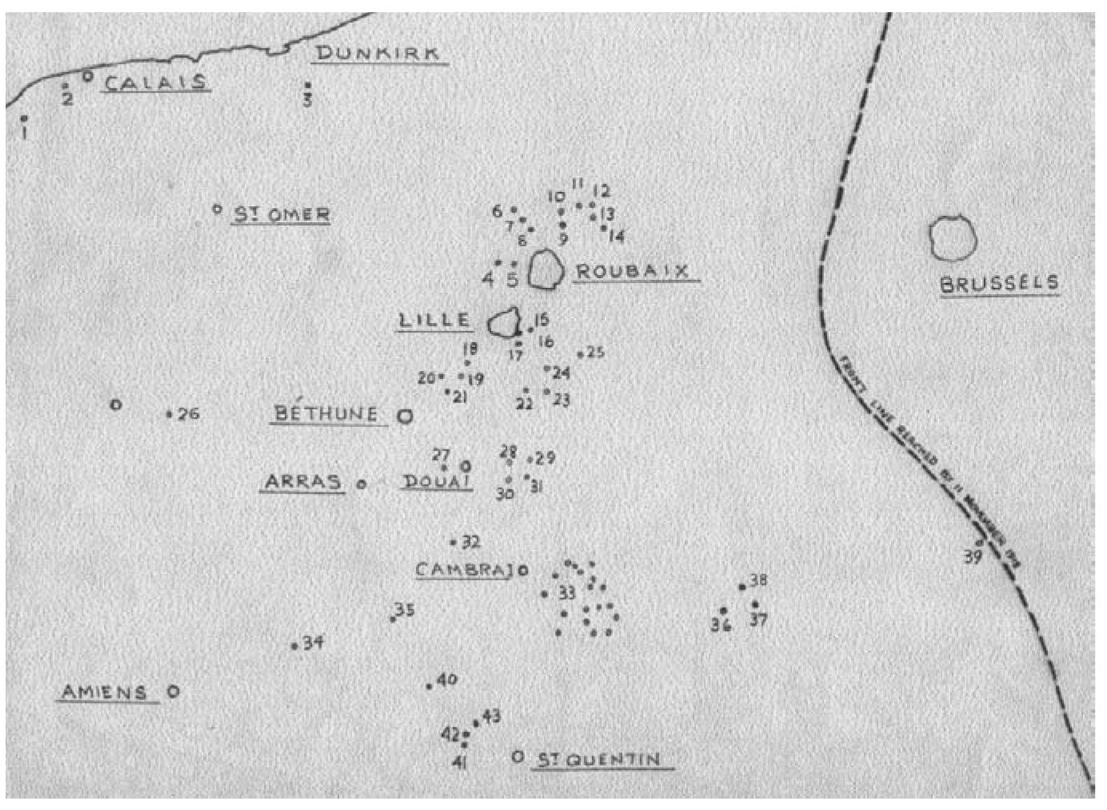

THE ITALIAN THEATRES OF OPERATIONS

The British Air Service did not operate on the Italian Front until November 1917, after the Italian retreat from Isonzo, when the Italian Brigade was formed and dispatched. With the intervention of the Allies, the Austrians retreated and this was then turned into a rout. Cooperation with the Russians in this theatre commenced in the latter part of 1916. The Italian theatre of operations in 1918 was divided between northern and southern Italy. The RAF squadrons in the north supported the Italian armies facing the Austro-Hungarian forces. The air tasks were shared by British, French and Italian units. The RAF squadrons in the south were concerned principally with the containment of the enemy naval threat posed by Austro-Hungarian and German surface vessels and submarines operating from ports in the Adriatic. The protection of Britain’s trade and reinforcement routes through the Mediterranean Sea meant stationing naval units in Gibraltar, Malta and Alexandria in Egypt. Land operations in Albania had also to be supported, and the deployment of RAF squadrons in Italy and Malta reflected these operational requirements. Although all the deployments in this chapter are given for 11 November 1918, it is worth remembering that the Allies negotiated a separate peace with Austria-Hungary on 4 November.

Northern Italy

The Piave offensive by the Austro-Hungarian forces in June 1918 was meant to defeat the Italian armies facing them across the River Piave. After initial successes, the Italians finally drove them back across the river, and the front was again stabilized. The RAF’s contribution to the land operations comprised ground attack, artillery observation, reconnaissance and air fighting. The ground-attack squadrons were No. 66, based at San Pietru, in Gu, and No. 28 at Sarcedo, equipped with Camels. The RE8s of No. 34 Squadron based at San Luca carried out artillery observation reconnaissance. This was often a very hazardous task since the observer would have his eyes down for most of the time and could easily miss enemy fighters swooping down from above. The Bristol fighters of No. 139 Squadron based at Arcade provided fighter and escort patrols. Major W.G. Barker VC, DSO, MC, who was the commanding officer of No. 139 Squadron during 1918, brought down fifty-three German aircraft and ranked seventh among the air aces. The aircrews who fought in direct support of the land forces were called ‘corps’ pilots, whereas the fighter pilots were called ‘Army’ pilots. To gain awards for valour was much more difficult for the ‘corps’ pilots since success was not measured in numbers of aircraft shot down.

Southern Italy

The RAF squadrons based in southern Italy, as has been said, were principally involved in containing the threat posed by enemy naval forces. Not surprisingly, all the RAF units involved were ex-RNAS squadrons, which all had the old numbers prefixed with 200 when the RAF took them over in April 1918. In view of the activities of enemy submarines in the Mediterranean and Adriatic, the work of the aircraft engaged in anti-submarine duties was of a most important character. In the early part of 1917 a wing was formed in southern Italy to assist the Otranto barrage in closing the southern end of the Adriatic to enemy submarines, and in bombing the Austrian naval ports in the Adriatic. These units also assisted materially in protecting convoys and in harassing submarines in all parts of the Mediterranean. Other functions were the bombing of lines of communication and places of military importance in Turkey and Albania, and the defence of Allied territory from enemy aerial attack.

DH9s of No. 226 Sqn at Taranto/Pizzone.

THE ITALIAN THEATRES AND MALTA – 11 NOVEMBER 1918

22 OPERATIONS AND TRAINING

MIDDLE-EASTERN THEATRES – EGYPT, PALESTINE AND IRAQ

Egypt

The RFC had forces protecting the Suez Canal and its sea approaches as soon as it was known that the Turks intended attacking the canal early in 1915. With the build-up of a training organization in 1916, the RFC was able to provide units for Mesopotamia (Iraq) and Salonica in Greece. The RFC organization became a brigade based on Egypt, then, in 1917, a major-general’s command. By October 1918 in Egypt, there was one training brigade of eight squadrons, three schools of special flying, one cadet wing and a school of military aeronautics. It was then possible to support one brigade of seven squadrons in Palestine, one wing of three squadrons in Mesopotamia and one wing of three squadrons in Macedonia.

Palestine

The final Allied offensive of the war against the Turks in Palestine began on 17 September 1918. Air power played a very important part in the offensive, and units of the RAF and RAAF (Royal Australian Air Force) were in action against German and Turkish telephone exchanges, and telegraph offices at Tulkarm, Nablus and Afula were bombed. Thus all contact between General von Liman and his subordinate commanders was severed and the main German airfield at Jenin was put out of action. During the ensuing seven days roads, railways and troop concentrations were bombed. On 20 September Allenby’s troops entered the Jezreel Valley. As the Turks retreated from Tulkarm and Nablus, the RAF and RAAF harried the retreating forces, creating such carnage that some pilots asked to be spared any future missions. The Turks had been overwhelmed by British airpower.

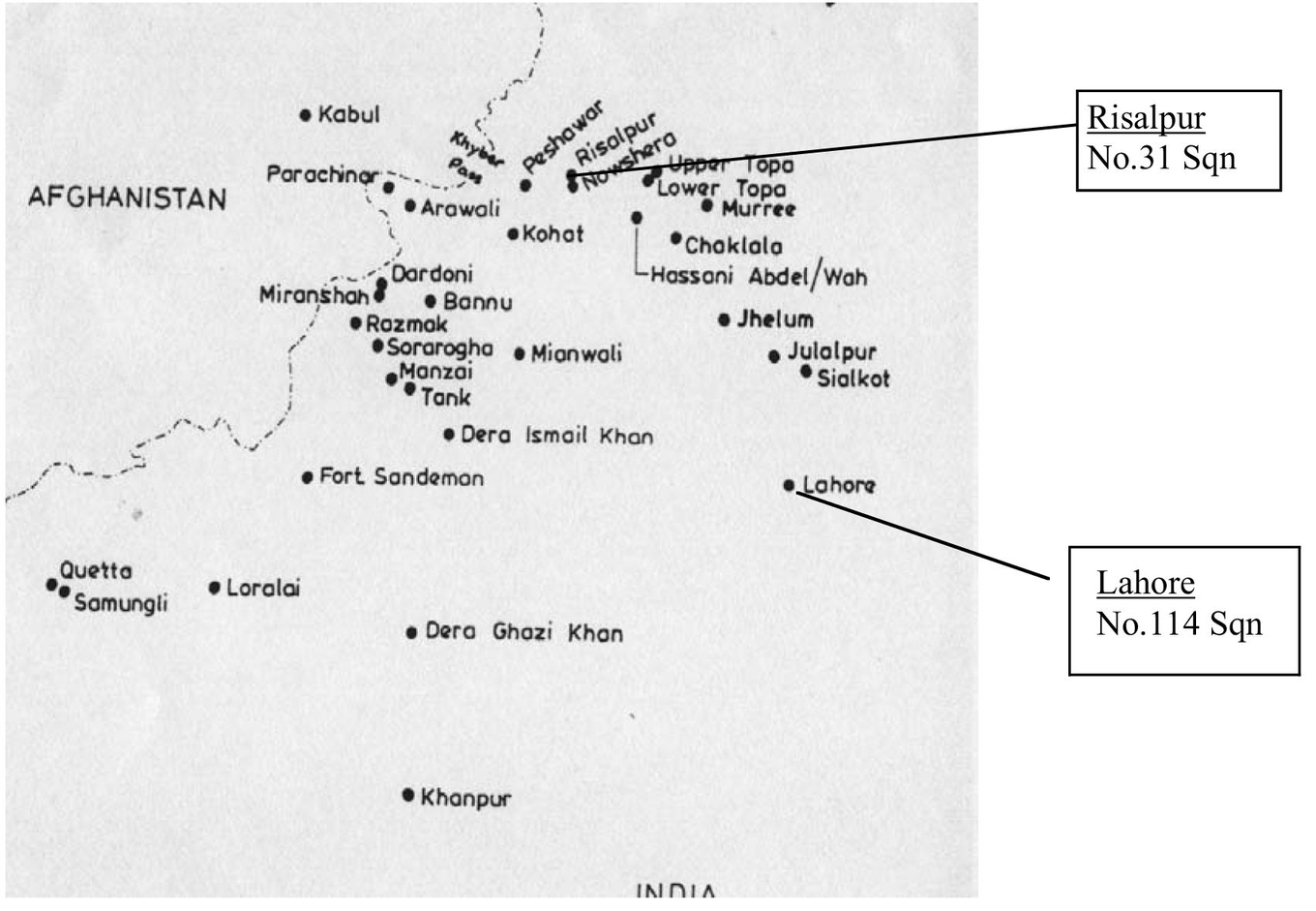

Mesopotamia (Iraq)

The RFC in Mesopotamia in 1915 consisted of a composite unit of aircraft sent from Egypt. The air force personnel in 1915 were titled ‘air unit personnel’ gazetted to the RFC as A Flight. On 4 November 1915 a reinforcement draft arrived at Basra comprising a flying squadron headquarters and B Flight to be added to the existing unit (A Flight), which was then titled No. 30 Squadron. This unit was severely handicapped through lack of machines, climatic conditions and inadequate personnel. So in 1917 an extra unit, No. 63 Squadron, was sent out to form a wing. This came under the command of the Middle-East Brigade. In March 1918 No. 72 Squadron arrived at Basra, and the wing rapidly gained air ascendancy. Air supremacy was maintained for the remainder of the war. At the cessation of hostilities all three squadrons were equipped with Martinsyde ‘Elephants’ and were deployed as shown on the map opposite.

A scene photographed on 20 September 1918 on the Nablus – Beisan Road.

RE8 of 142 Sqn, Palestine.

SE5As of III Sqn, also in Palestine.

MIDDLE-EASTERN THEATRES – PALESTINE, EGYPT AND IRAQ, 11 NOVEMBER 1918

The assets of No. 221 Squadron were absorbed by No. 222 Squadron in October 1918, but since 221 Squadron was reconstituted with DH9s in December it has been left as a Mudros unit.

THE AEGEAN THEATRE

Group Origins The origins of the Aegean Group RAF, composed largely of ex-RNAS units, did not follow the European pattern of simply adding the Number 200 to the RNAS squadron number. Air Organization Memorandum 800 provided that, on 1 April 1918 ,the numbering of ex-RNAS units remote from the European theatre would be Nos 220 to 227 Squadrons inclusive. Of these, the ex-RNAS units in the Aegean were lettered A, B, C & D Squadrons, and these, according to best evidence, became Nos 222, 223, 220 and 221 Squadrons RAF respectively. The map above shows the location of these and the other units in the Aegean theatre on 11 November 1918. The units belonged to Nos 62 and 63 Wings of No. 15 (Aegean) Group.

Operations On 14 September the Allies launched their offensive on the Salonika front. On that day the Austrians asked the Allied Powers, together with the USA and the neutrals, to agree to a ‘confidential and non-committal exchange of views’ on neutral soil with a view to seeing if peace might be possible. Some 36,000 Serb, Italian and French forces were in action against German and Bulgarian forces. On 16 September two Bulgarian regiments mutinied and the Germans had to act to prevent a rout. No German forces were available for reinforcement, the nearest being a brigade in the Crimea. The Bulgarian defeats in Macedonia led to unrest in the Bulgarian capital, Sofia, and on 25 September British forces entered that country. With the Germans in retreat, all hope of holding the Balkans was gone, and the southern approaches of the heartland were open to Allied advance. The squadrons based in the northern Aegean were employed in bombing, artillery observation, reconnaissance and Army cooperation in support of the land campaign against the Central Powers. Only at Mudros were there units employed in maritime reconnaissance and anti-submarine work. Below is the report from the RAF Aegean Group based at Mudros, dated 27 October 1918:

Five DH machines of No. 226 Squadron left Marsh aerodrome at 09.15 hrs on the 25th October. And landed at Imbros to refuel. They left again at 10.50 hrs to carry out a photo reconnaissance of Constantinople. Attacked by German machines … a Fokker and an Albatross shot down … anti-aircraft fire accurate. All aircraft landed safely at Imbros then returned to their base at Lemnos.

It is clear from reports at this time that San Stefano airfield was frequently reconnoitred, as was Hardar Pasha railway station. Shipping was also observed. No. 220 Squadron at Imbros was also actively engaged in reconnoitring railway stations for evidence of troop and materiel movement.

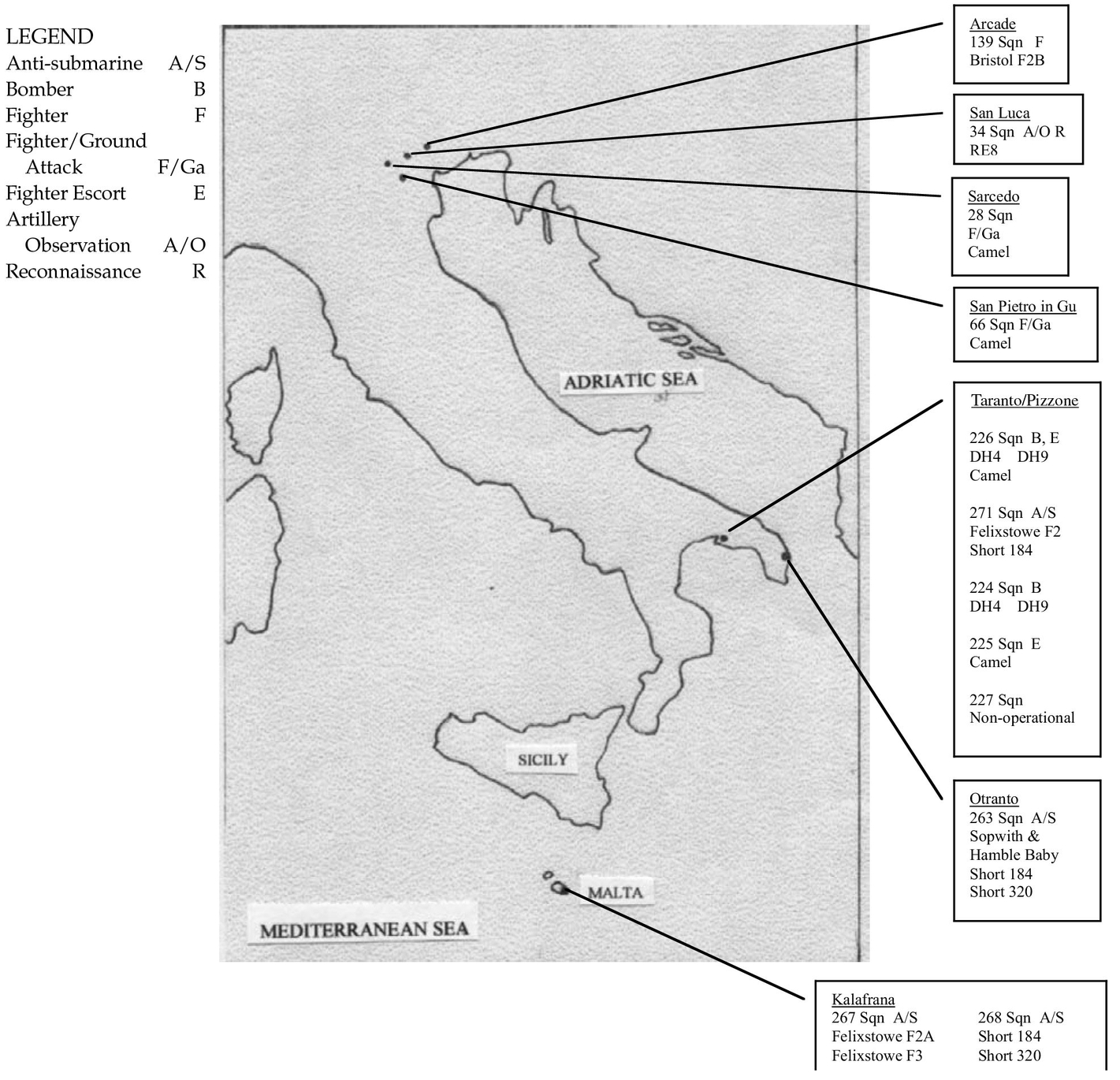

INDIA AND ADEN, 11 NOVEMBER 1918

Operations in India

In 1917 two squadrons of the RFC were provided for India, where they played an important part in quelling trans-frontier risings. As early as 1916 a flight of aircraft had been dispatched from Egypt to play a useful part in an expedition against Darfur. At the Armistice only two RAF squadrons were stationed in India – No. 114 Squadron at Lahore and No. 31 Squadron at Risalpur. These were engaged in sporadic activity in support of the Waziristan Field Force. Extracts from squadron records show that these units were engaged almost exclusively on training. The greatest threat to life was cholera, which claimed some lives, and influenza outbreaks could reduce squadron manpower availability to less than 50 per cent.

No. 31 Squadron (HQ and three flights) – Risalpur for week ending 9 November 1918

| Sunday | Four Lewis gun practices for training pilots and observers. |

| Monday | Two practice recces including recce to Tarbala. |

| Tuesday | Four bomb-dropping practices. Twenty 20 lb bombs dropped. Training of pilots and observers. |

| Wednesday | Practice flight over Camera Obscura. Training of pilots and observers. |

| Thursday | One photo-recce where 48 plates were exposed. Training of pilots and observers. |

| Friday | Two cross-country flights. Lahore to Risalpur, delivery of a machine by air. |

| Saturday | Test flying for officer joining the RAF, practice flights, engine rigging and tests. |

General The average sick and unavailable for duty is 22% of strength. Influenza epidemics still causing considerable loss of efficiency in the work of the squadron but is now apparently decreasing in severity.

Total flying times: By Pilots – 19 h 27 min By Observers – 7 h 7 min

No. 114 Squadron (HQ and B Flight) – Quetta [Records do not show on which days during the week ending 9 November the following activities took place.]

Day 1 Five machines flew across country from Quetta to Lahore (about 700 miles). Formation flight Quetta to Jacobabad, Reti, Lodran, Multan, Montgomery and Lahore. En route photographs were taken of landing grounds etc., fourteen exposures being made. The flight was completely successful and the five machines arrived simultaneously at Lahore in excellent formation. The times were as follows:

| Quetta to Jacobabad | 3 h 50 min |

| Jacobabad to Reti | 2 h 25 min |

| Reti to Multan | 3 h 32 min |

| Multan to Montgomery | 1 h 47 min |

| Montgomery to Lahore | 1 h 43 min |

| 13 h 17 min |

Day 2 36 photographs taken for mosaic of Lahore.

Day 3 Test flight for officers joining the RAF.

Day 4 Engine and rigging tests.

General HQ and B Flight moved from Quetta to Lahore. The average sick and unavailable for duty is 13% of strength.

Total flying hours: By Pilots – 129 h 44 mins By Observers – Nil

No. 114 Squadron (A Flight) – Lahore

Day 1 Seventeen contact patrol practices over aerodrome for purpose of training special class of infantry officers, NCOs and men.

Day 2 Test flights for officers joining the RAF.

Day 3 Engine and rigging tests.

General The average sick and unavailable for duty is 13% of strength.

Total flying hours By pilots – 7 h 26 min By Observers – Nil

Operations in Aden

Aden Flight Operations for the week ending 12 November 1918

Operations Active operations ceased on 31 October owing to the Armistice with Turkey and by orders of HQ Aden Field Force flying ceased on that date.

General During the week all engines fitted to machines have been top overhauled. The four machines erected have been thoroughly examined and overhauled. Two engines have also been completely overhauled in workshops. All engines on charge are now serviceable. In spite of the influenza epidemic the death of the flight remains satisfactory.

There have so far been no cases of influenza in the unit. There have been two admissions to hospital since the last report, with minor ailments.

[Note: the word ‘death’ has been underlined in the text above and a question mark was placed against it in the original records due to this amusing typographical error.]

Total flying hours: 1 h 19 min

Signed Major SOII for Director of Aeronautics in India

THE NORTH-WEST FRONTIER OF INDIA, 11 NOVEMBER 1918

A Bristol Fighter 2B of No. 31 Squadron in India. These aircraft replaced the BE2Es in June 1919, and remained in service in India until 1931.

A BE2E at Tank on the North-West Frontier during operations against the Mahsuds.

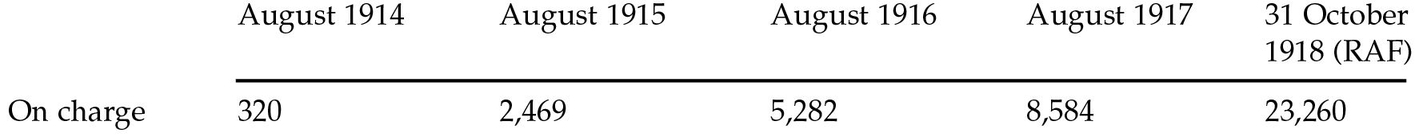

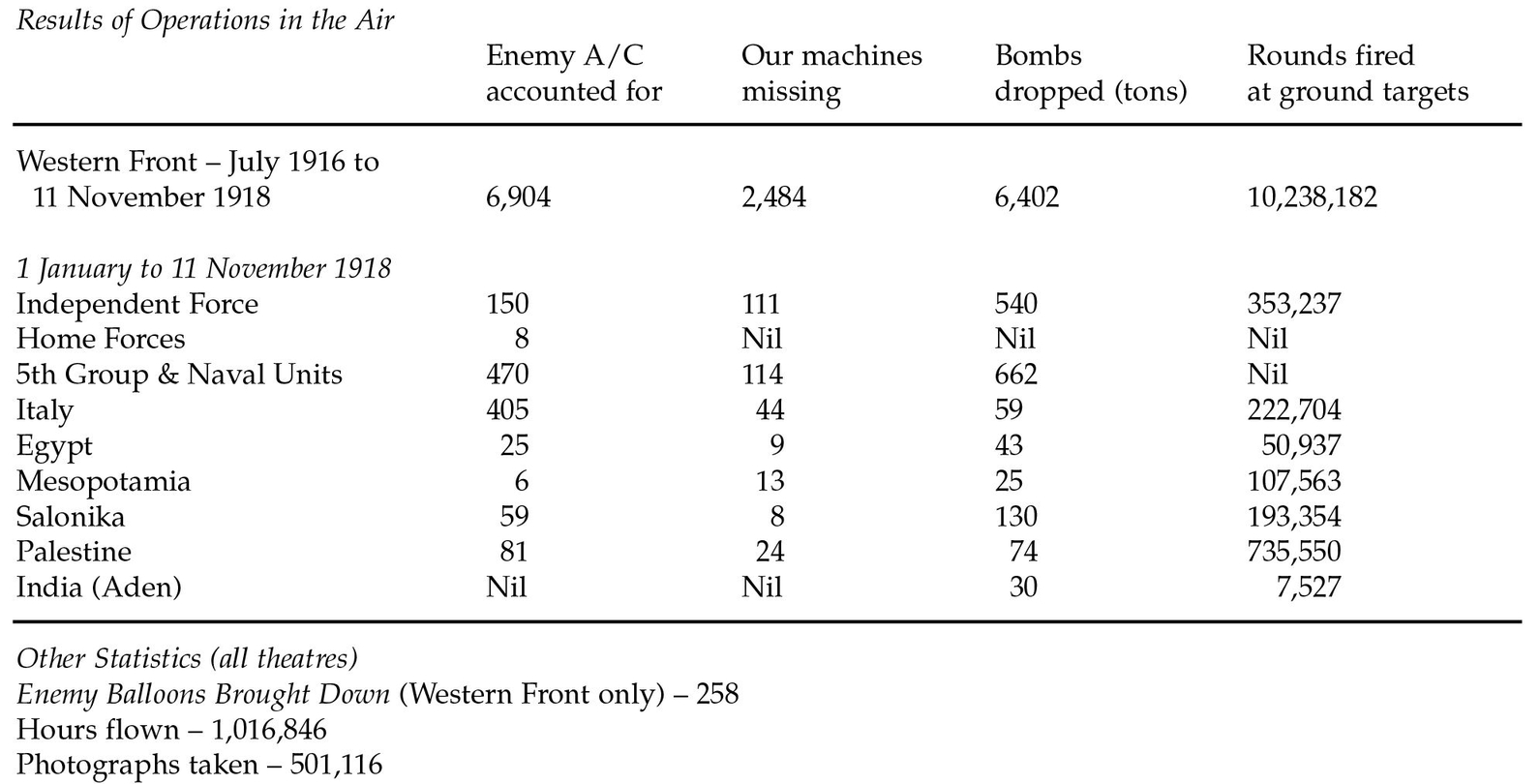

State of the Royal Air Force at the cessation of hostilities. Source: National Archives AIR/I/718

Service Squadrons maintained A comparison between the active operational squadrons on strength in August 1914 and 31 October 1918 shows how massively the RAF (RFC and RNAS) grew over the war years:

| Theatre of Operations | August 1914 | October 1918 |

|---|---|---|

| Western Front | 4 (RFC) | 84 + 5 flights |

| Independent Force | – | 10 |

| 5 Group | – | 3 |

| India | – | 2 |

| Italy | – | 4 |

| Middle East | – | 13 |

| Russia | – | 1/2 |

| Home Defence | – | 18 |

| Naval Units | 1 (RNAS) | 64 |

| 5 | 200 + 5 flights |

Expansion of Motor Transport (RFC only)

The statistics below show the enormous increase in aerial photography, an aspect of reconnaissance that not only informed Army commanders of enemy troop positions but helped air commanders to assess the effectiveness of bombing raids.

The Qualities of Aircraft and Aircrews

Before moving on to describe the fortunes of the RAF in the 1920s, a little thought is given to the quality of aircraft and aircrews at the cessation of hostilities in 1918.

Quality of Aircraft The aircraft of the RFC/RNAS were developed from the flimsy Blériot-like aeroplanes that took to the air in 1914 to the much more powerful machines with longer range, armament and bombs that were on strength in November 1918. Starting out as a reconnaissance vehicle, during the war the aeroplane had also become a reconnaissance seaplane, a torpedo-bomber, a land bomber, a ground-attack aircraft and a fighter. By 1918 a four-engined bomber, the HP V/1500, flying from Norfolk, had the range and bomb-carrying capacity to reach and cause serious bomb damage to Berlin. The reliability of engines had also increased to the point where, within a year of the war’s ending, a Vimy bomber was able to fly the Atlantic Ocean, only ten years after Blériot’s crossing of the English Channel. The Camel, Snipe, SE5A and the Pup were all fighters with enhanced service ceilings and the speed to outclimb adversaries. Although the Camel could be very tricky in a turn, once a pilot had mastered this aircraft he had a formidable weapon, and the Camel accounted for over 2,800 enemy aircraft. The SE5A was easy to fly and was strong. Both aircraft had a similar service ceiling of some 22,000 feet and an endurance of two and a half hours, although the SE5A was faster, with a top speed of 138 mph. Two aircraft that were to survive the war and go on to serve the RAF into the 1930s were the Bristol F2B and the Airco DH9A. The DH9A could carry a larger bomb load than the Bristol Fighter, 250 lb as against 112 lb, but both were used as general-purpose aircraft in Ireland, India and Mesopotamia during the inter-war years. Their rugged construction meant that they could operate in hostile environments. The biplane, and even more so the triplane, was very manoeuvrable, and because there were two wings to share the aircraft’s load, they were not so highly stressed. Manoeuvrability, rate of climb, good top speeds and sturdy and simple construction were the hallmark of the RAF’s best fighter aircraft in 1918. Finally there was the Avro 504, of which variants A to L were built. Although used as a home-defence fighter and by the RNAS as a bomber, its most outstanding role was as an ab initio trainer. Altogether over 10,000 of these aircraft were built, yet when it was first conceived by Alliot Verdon Roe he expected only a handful to be ordered.

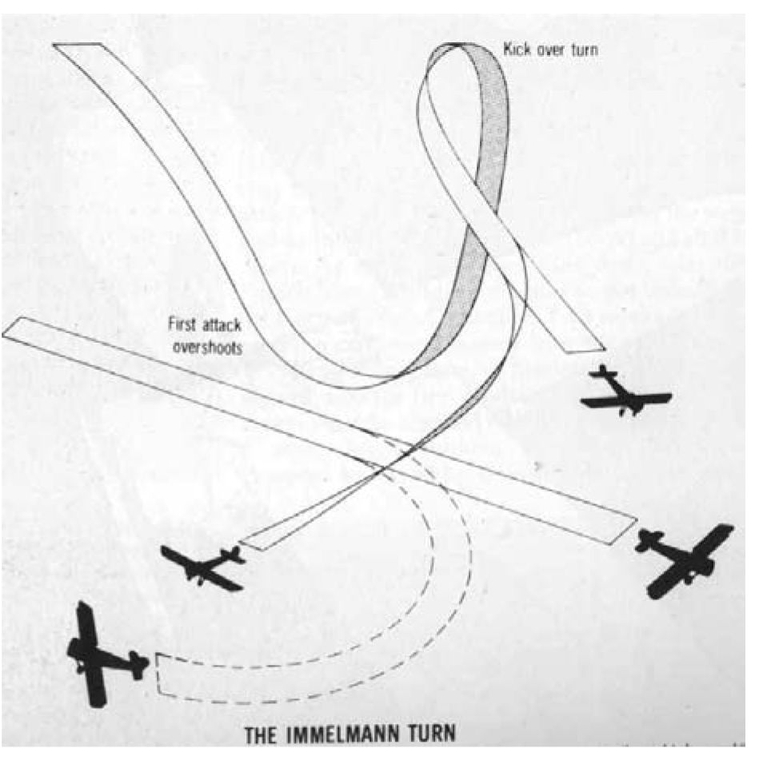

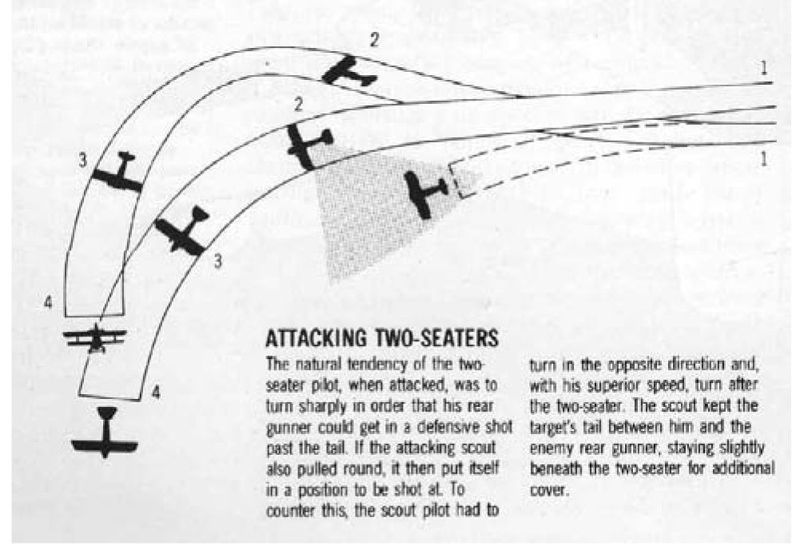

Quality of Aircrews As has been pointed out, the First World War began with the aeroplane intended simply as a reconnaissance vehicle. When air fighting began, both sides developed tactics in an attempt to gain an advantage, but this was always temporary since the other side would seek to redress the balance. The ‘Lufbery Circle’ and the ‘Immelman Turn’, attributed to the pilots named, provide examples of how tactics were developed, given the performance of adversarial aircraft.

What made these ‘Knights of the Air’ was a recognition of general rules of survival in combat. There were no self-sealing fuel tanks, no protective armour and no parachutes. A fighter pilot survived long enough to become a veteran if he overcame the initial desire to open fire at very long range instead of waiting until he got in close. By 1917 the lone pilot had been replaced by the patrol leader, who would need to see the enemy first and lead his patrol to effect surprise and bring the maximum number of guns to bear on the enemy. Most air battles lasted only a matter of minutes, and the leader needed to keep calm and use sun and cloud to his advantage. During the war, air fighting schools and night bombing schools proliferated to keep pace with the needs of squadrons at home, on the Western Front and further afield.

Camel Tactics

When the war ended the RAF had only the experience of the one conflict upon which to build an air force for the future. The service was left with the biplane, canvas and wood construction, the open cockpit, the Lewis and Vickers gun. It was to be almost twenty years before stressed skin, closed cockpit, eight-gun Browning- or cannon-armed, all-metal monoplane fighters took their place on RAF squadrons.