Chapter 3

The Locarno Honeymoon, 1925 to 1930

The Locarno Treaty – State of the RAF – Special Reserve and Auxiliary Squadrons – University Air Squadrons – Air

Operations: the Middle East and India – the Schneider Trophy Races – the RAF Display – A & AEE Martlesham – MAEE

Felixstowe – Parachutes and pilotless bomber – Airships – Civil Aviation – Training and Air Exercises – Trenchard’s Farewell

The Locarno Honeymoon

During his brief period in office as the first Labour prime minister in history, Ramsay MacDonald set in motion in 1924 a series of events designed to strengthen the League of Nations. In the context of RAF expansion and the climate of hope engendered by the new League in finding ways to bring about lasting world peace, successive British governments had to balance the needs of home defence and defence of Imperial outposts with the need to demonstrate to the world community that Britain was serious about international disarmament. The period from 1925 to the end of the decade has been described as the Locarno honeymoon. The Kellogg – Briand Pact, which was to follow in 1928, further strengthened the determination of the major powers for peace. In spite of reparations that Germany had to pay to the Allied Powers resulting from the ‘war guilt’ clause in the Versailles Treaty for damage and casualties inflicted in the First World War, that country under Stresemann’s leadership was doing well economically. But all that was to come to nought with the ‘Wall Street Crash’ of 1929, which was followed by a severe economic depression that threw thousands out of work in the USA and Western Europe. The rise of the Fascist dictators and Japanese aggression in Manchuria (Manchukuo) in 1932 led to the failure, in Geneva, of the entire disarmament process. But these events are dealt with in Volume II. In 1925 Trenchard had his imperial policing role to fulfil and a modest re-equipment programme to implement as part of the expansion plan.

The Locarno Treaties, 1925/6 One of these treaties was the Rhineland Pact, which confirmed the sanctity of the borders of Belgium, France and Germany. It also confirmed the demilitarized zone of Germany west of the Rhine in which Germany was not permitted to station troops. Another treaty, the Treaty of Arbitration, bound Germany and France to accept mediation in disputes, and Germany made similar arrangements with Belgium, Poland and Czechoslovakia, with France guaranteeing to protect them in the event of German aggression. To satisfy Russian fears Germany renewed the Treaty of Rapallo. Finally, later in 1926, Germany was admitted to the League of Nations, with a seat on the Council of the League.

The Kellogg – Briand Pact The French minister Briand produced a plan for collective security under the League. France and the USA would sign a pact to renounce war, and this was enthusiastically received by Kellogg, the American Secretary of State, who suggested that more countries be invited to join the declaration. In 1928 sixty-five League members signed the Pact. But this left open the vital question of what to do if any country that had solemnly signed the Pact subsequently committed an act of aggression against another member of the League, or any other country. There was no international force under the League’s control that could intervene to prevent or curtail conflict. Sanctions were always one method of bringing pressure to bear on an aggressor. Indeed sanctions were later used against Mussolini over Italy’s aggression against Abyssinia, but they had the perverse effect of throwing Mussolini into an alliance with Hitler to form the Rome – Berlin Axis. In the mid- to late 1920s Hitler had still to become a threat to world peace following the failure of his attempted coup in 1923 and his spell in prison. Mussolini, although heading a Fascist regime, was not at that time a threat to any other state. And so in the heady days of peace in the mid-1920s these thoughts were at the back of statesmen’s minds.

The State of the RAF

The RAF was continuing with its policy of Imperial policing, and at home was carrying out a modest expansion towards the eventual target of fifty-two Home Defence squadrons. Trenchard had begun the slow process of modernizing the inventory of RAF aircraft, with aircrews wedded to the biplane and open cockpits. A start, however, had been made to move towards all-metal aircraft construction and greater streamlining.

1925

Air Estimates, 1925/6 On 19 February1925, Sir Samuel Hoare addressed Parliament on the debate on the Air Estimates for 1925/6. Parliament was being asked to authorize an expenditure of £15,513,000, compared to £14,720,000 for 1924/5. The cost of air-control operations and RAF activities afloat meant an additional income from the Colonial Office for Iraq (£2,744,100) and Palestine/Transjordan (£372,600), and from the Admiralty a vote of £1,320,000 for the Fleet Air Arm.

RAF strength, 1925

Sir Samuel Hoare then went on to inform the House of the strength of the RAF. Apart from training units and establishments there was an equivalence of fifty-four squadrons. Of these, forty-three squadrons and two flights were RAF squadrons, and there were twenty-one flights, each of six aircraft, for the Fleet Air Arm. Of the established squadrons their deployment was as follows:

| United Kingdom | – 25 squadrons + 1 flight |

| Iraq | – 8 squadrons |

| India | – 6 squadrons |

| Egypt/Palestine | – 4 squadrons + 1 flight |

Of the twenty-five squadrons in the United Kingdom, eighteen were regular Home Defence squadrons. During the financial year a further two regular squadrons were to be added, togther with one Special Reserve squadron and four Auxiliary squadrons, about which more later. It may be recalled, from Chapter 2, that there were to be fifty-two Home Defence squadrons in the expansion plan, but that no completion date for this plan had been specified. The Air Minister’s presentation to Parliament on 19 February 1925 prompted The Times to warn that Parliament had hardly erred on the side of extravagance. Given that only two extra regular squadrons were to be formed that year, the paper observed that it would take until 1936 to raise the strength to just forty squadrons. Sir Frederick Sykes, the former Chief of the Air Staff, asked about wastage, and Hoare reported that, for the twelve months ended 31 October 1924, 339 aircraft had been written off charge following accidents and that eighty-one aircraft had been lost through fair wear and tear, service terminology for simply wearing out. The average age of aircraft, he said, was about five years, and the average flying life about 130 hours.

1926

Changes in Organization

Source:Air Ministry Weekly Order 354/1926

This Air Ministry Weekly Order laid down the changes to areas and groups, and the allocation of stations to groups. The units listed in the following texts will give the reader some idea of how complex the organization of the Royal Air Force had become by 1926, and all for £15.5 million, less than the price of one Tornado MRCA today (2004). The Home Defence Force, comprising the Wessex Bombing and the Fighting Areas, were the manifestation of the expansion plan, which provided for fifty-two bomber and fighter squadrons to defend the United Kingdom. The Inland Area comprised all those stations involved in flying, technical and recruit training and for the provision of a host of support services. It also included stations on which Army Cooperation squadrons were based.

Inland Area On 1 June 1926, Headquarters of the Inland Area moved to Bentley Priory, Stanmore. The Inland Area was then organized into three groups. Owing to the changes made to the organization of groups at home, some units were based temporarily at a station not in that group, so see the notes below.

No. 21 Group Formed on 12 April at West Drayton. The No. 21 Group stations were Altrincham, Ascot, Henlow, Ickenham, Kidbrooke, Martlesham, Milton, Orfordness, Ruislip, Shrewsbury, West Drayton and Uxbridge. The following units came under Group command:

Reception Depot, West Drayton

No. 1 Stores Depot, Kidbrooke

Port detachment, No. 1 Stores depot, South Dock, West India Dock, London E14

School of Store Accounting and Storekeeping, Kidbrooke

Medical Stores Depot, Kidbrooke

No. 2 Stores Depot, Altrincham

No. 3 Stores Deport, Milton

No. 4 Stores Depot, Ickenham

The Packing Depot, Ascot

Record Office, Ruislip

RAF MT Depot, Shrewsbury

Home Aircraft Depot, Henlow

Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment, Martlesham

Detachment, Orfordness

RAF Depot (including School of Physical Training), Uxbridge

Superintendent, RAF Reserve, Northolt

Headquarters Air Defence Great Britain (administration only), Uxbridge

RAF Officers’ Hospital (administration only), Uxbridge

Note: Nos 23 and 43 (Fighter) Squadrons belonging to Fighting Area were temporarily based at Henlow, a 21 Group station.

No. 22 Group Formed on 12 April at Farnborough. The No. 22 Group Stations were Farnborough, Larkhill and Old Sarum. The following units came under Group command:

School of Photography, Farnborough

Experimental Section, Royal Aircraft Establishment, Farnborough

No. 4 (Army Cooperation) Squadron, Farnborough

School of Army Cooperation, Old Sarum

No. 16 (Army Cooperation) Squadron, Old Sarum

School of Balloon Training, Larkhill

No. 13 (Army Cooperation) Squadron, Andover

No. 2 (Army Cooperation) Squadron, Manston

Detachment of Electrical and Wireless School accommodated at Worthy Down

No. 23 Group Formed on 12 April at Spittlegate. No. 23 Group Stations were Digby, Eastchurch, Flower Down, Manston and Sealand. The following units came under Group Command:

No. 1 Flying Training School, Netheravon

No. 2 Flying Training School, Digby

No. 5 Flying Training School, Sealand

Armament and Gunnery School, Eastchurch

School of Technical Training (Airmen), Manston

Central Flying School, Upavon

Electrical and Wireless School, Flower Down

Notes: There was no No. 3 FTS, and No. 4 FTS was at Abu Sueir, Egypt. Temporarily the following squadrons belonging to Wessex Bombing Area and No. 22 Group were located at No. 23 Group stations: from Wessex Bombing Area, No. 207 (Bombing) Squadron at Eastchurch, No. 9 (Bombing) Squadron at Manston and from No. 22 Group, No. 2 (Army Cooperation) Squadron at Manston.

Home Defence Force,Air Defence of Great Britain (ADGB), formed 1.1.25

Wessex Bombing Area The Wessex Bombing Area comprised the following units:

No. 12 (Bombing) Squadron, Andover

Staff College Andover (administration only)

No. 58 (Bombing) Squadron, Worthy Down

No. 11 (Bombing) Squadron, Netheravon

No. 100 (Bombing) Squadron, Spittlegate

No. 39 (Bombing) Squadron, Spittlegate

No. 7 (Bombing) Squadron, Bircham Newton

No. 99 (Bombing) Squadron, Bircham Newton

No. 9 (Bombing) Squadron, Manston

No. 207 (Bombing) Squadron, Eastchurch

Note: Temporarily the following units of Inland Area were located at stations of the Wessex Bombing Area: from No. 22 Group, No. 13 Squadron at Andover and the Electrical and Wireless School Flight at Worthy Down, and from No. 23 Group, Group HQ at Spittlegate and No. 1 Flying Training School at Netheravon.

Fighting Area Fighting Area comprised the following units:

No. 32 (Fighter) Squadron, Kenley

No. 24 (Communications) Squadron, Kenley

No. 56 (Fighter) Squadron, Biggin Hill

Night-Flying Flight, Biggin Hill

No. 41 (Fighter) Squadron, Northolt

Communications Flight, Northolt

No. 25 (Fighter) Squadron, Hawkinge

No. 17 (Fighter) Squadron, Hawkinge

No. 19 (Fighter) Squadron, Duxford

No. 29 (Fighter) Squadron, Duxford

No. 111 (Fighter) Squadron, Duxford

No. 3 (Fighter) Squadron, Upavon

No. 23 (Fighter) Squadron, Henlow

No. 43 (Fighter) Squadron, Henlow

Note: Temporarily the following units were located at stations of the Fighting Area: No. 600 Auxiliary Air Force Squadron and No. 601 Auxiliary Air Force Squadron at Northolt, Central Flying School (No. 23 Group) at Upavon and Superintendent of RAF Reserve (HQ Inland Area), also at Northolt.

Special Reserve and Auxiliary Command These were the new Special Reserve and Auxiliary squadrons that had just been formed manned by reservists, sometimes called the ‘weekend’ flyers:

No. 502 Special Reserve (Ulster) Bombing Squadron, Aldergrove

No. 600 (City of London) Bombing Squadron, Northolt

No. 601 (County of London) Bombing Squadron, Northolt

No. 602 (City of Glasgow) Bombing Squadron, Renfrew

No. 603 (City of Edinburgh) Bombing Squadron, Turnhouse

The Organization of Stations Paragraph 4 of this AMWO laid down the responsibility for administration and discipline. For example, a ‘Commanding Officer’ as opposed to an ‘officer commanding’ is an officer with specified disciplinary powers to award punishments and the authority to hold public and non-public funds. It was explained in Chapter 1 that the Royal Air Force had pieces of real estate, in the case of airfields large pieces of real estate, called RAF stations, and these were most often commanded by a group captain. As John James explains in Chapter 5 of his most excellent book The Paladins, the RAF had to decide whether it was going to copy the Army and have its officers spend much of their service with a regiment and be specialized in infantry, artillery and cavalry. That is to say, should RAF officers serve on a bomber, fighter, coastal or Army Cooperation wing, such wings comprising numbered squadrons that would stay together and move as titled wings? This was not to happen. The basic unit was to be an RAF squadron, which might serve as part of a numbered wing for a specific operation, such as the wings in India, but usually squadrons were allotted to groups. An officer would normally serve one tour with a squadron. He would therefore be posted to a squadron on a station. His immediate superior would be his ‘officer commanding’ the squadron, but his ‘commanding officer’ would be the Station Commander. When the squadron went to war the commanding officer stayed put in command of his piece of real estate. The RAF would appoint another officer to exercise overall operational command of squadrons that left their parent stations. That is not to say that individual officers did not specialize on, say, coastal or fighter aircraft, but any pilot could undertake operational conversion training to fit him to change role, for example from fighter to bomber. Technical and administrative personnel could be posted to a squadron and move with that squadron if it left its parent airfield on operations. Other technical and administrative personnel were simply posted to an RAF station to remain there to serve the needs of squadrons based there. Hence para. 4 states that where two or more units are located at a station then an officer will be appointed as Station Commander. If only one unit was located at a station the officer commanding the squadron could be given the powers of a commanding officer and serve in that dual purpose. Thus, when a station was established for a Station Headquarters, a station commander would be appointed. The station commander would be responsible for training, discipline and administration on his station, and his immediate superior would be the Air Officer Commanding the group to which his station belonged. If any female reader wonders why no reference is made to ‘his or her’ station, she is advised that from 1920 until 1938 the RAF was a male-only service.

1927

Air Estimates, 1927/8 The Air Estimates for the year 1927/8 were published on 5 March. Parliament was asked to vote for £15,550,000, which was a reduction of £450,000 on the previous year. Savings were made on personnel, works and buildings, but an increase was allowed for in spending on technical equipment, which included two new types of aircraft. The Air Minister made the point that, ‘This was the policy of replacing aeroplanes and engines of war-time design by modern types. Steady progress was being made and it was the intention that in future no more aircraft or engines of war-time designs should be bought.’ Sir Samuel Hoare made an allocation of £137,000 to subsidize Imperial Airways for its European services, and £93,600 for the Cairo – Karachi route. A further £111,000 would go to work at Croydon airport, which was due for completion in 1928. There would be £10,000 for a new wireless telegraphy station and £8,000 for meteorological services. The vote for the RAF was little changed.

1928

The Tenth Anniversary of the RAF On 1 April 1928, on the occasion of the tenth anniversary of the RAF, Lord Weir, the former Air Minister, and closely identified with its inception, sent a cable to Trenchard with these words:

I regard it as incomparably the most efficient Air Force in existence, creditable alike to British organization and British character. It is a welcome portent to the Empire that this new fighting Service affords opportunity not only to British qualities of courage, determination and enterprise, but also to the spirit of true scientific progress.

These were welcome words to someone who had worked so hard to fashion the RAF, always sacrificing quantity for quality and managing on a shoestring budget, all the time being buffeted by the predictable claims on the nascent RAF by the Royal Navy and the Army for the return of their air units. Even so, the ten years had not witnessed as great a change as might have been expected, partly owing to the lack of money. Was the Siskin, for example, such an advance on the Bristol Fighter? Did not the lumbering Vickers Virginia still not have the same ungainly appearance of the HP V/1500? The twin Vickers gun and the Scarff-mounted Lewis gun still remained supreme, together with open cockpits and biplane construction. Air-cooled radials were half the price of water-cooled engines and easier to install and service. Moving the radiators to the wings did mean that aircraft with water-cooled engines, like the Fairey Fox, could have a more streamlined appearance. Although engines were more powerful and reliable, speeds would not increase substantially until the monoplane was the norm.

1929

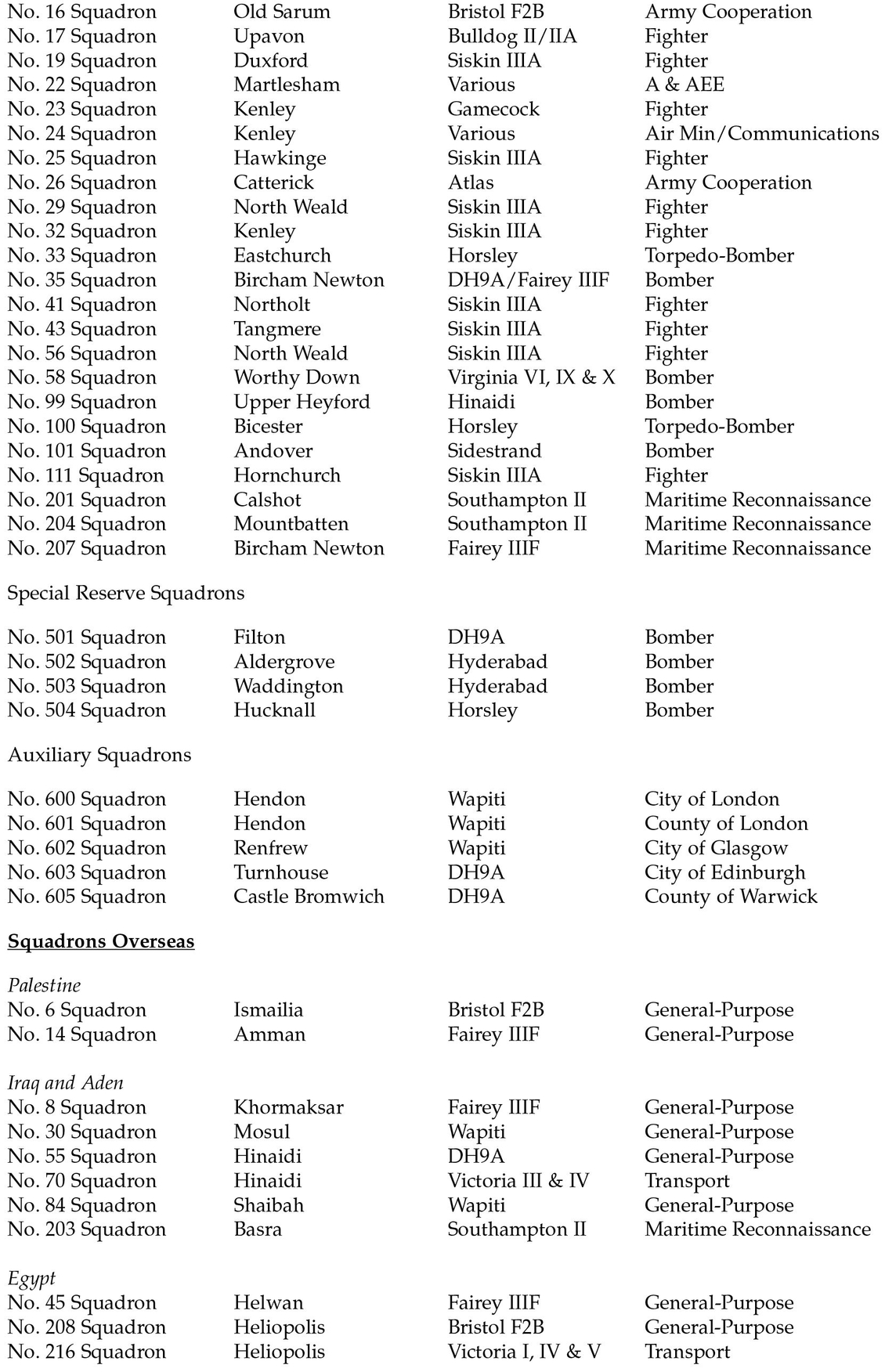

The Air Estimates, 1929/30 The figure announced was £16,200,000 net. In spite of the fact that the annual figure was reduced from the £16,563,000 of the previous year, seven squadrons would be added to the seventy-five then in existence. The annual figure does not tell the whole story. The Estimates were broken down into Votes. Two of these votes were of significance in determining how much was spent on men and machines. Vote 1 was for pay and allowances, and that rose from £3,401,000 the previous year to £6,585,000. Vote 3 was for warlike stores, i.e. aircraft and weapons, not barrack furniture and uniforms. Vote 3 rose from £6,567,000 to £6,585,000. The small rise for Vote 3, although marginal, can be misleading. Pay is for services rendered by the week or the month. Money spent on aircraft is spread over many years, given the time from drawing board to prototype, and from there to squadron service. More squadrons meant more personnel, but not necessarily more RAF stations. Permanently commissioned officers would be needed in such numbers as would be needed to provide for full career posts and to ensure that there was a sufficiency of permanent officers to provide a nucleus in the event of sudden expansion. The remainder would be on short-service engagements followed by a number of years in the RAF Reserve of Officers, when the RAF would try to ensure that such officers were educationally prepared for jobs outside the service. In the event, during the rapid expansion of 1938, and using Bomber Command as an example, there were insufficient permanent officers to provide middle management. There were only twelve wing commanders against 325 pilot officers.

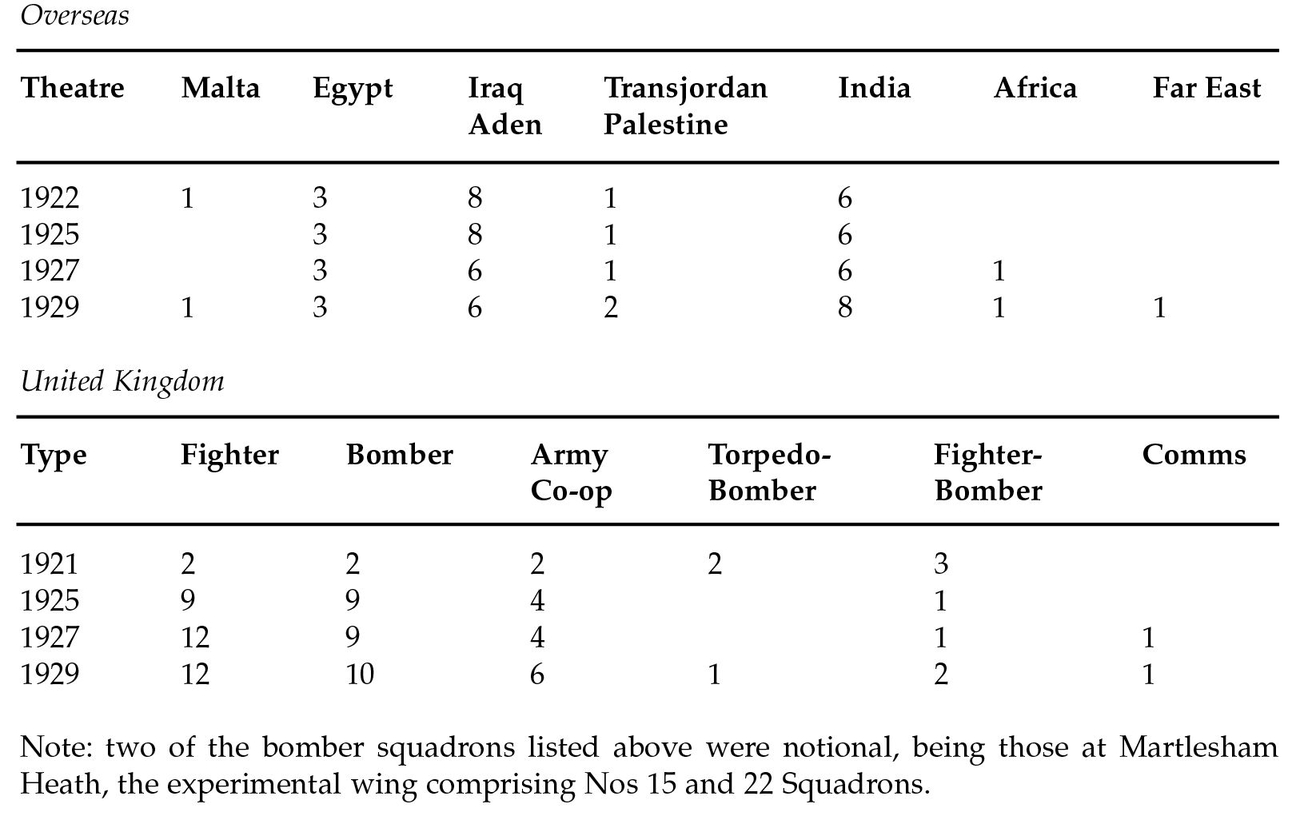

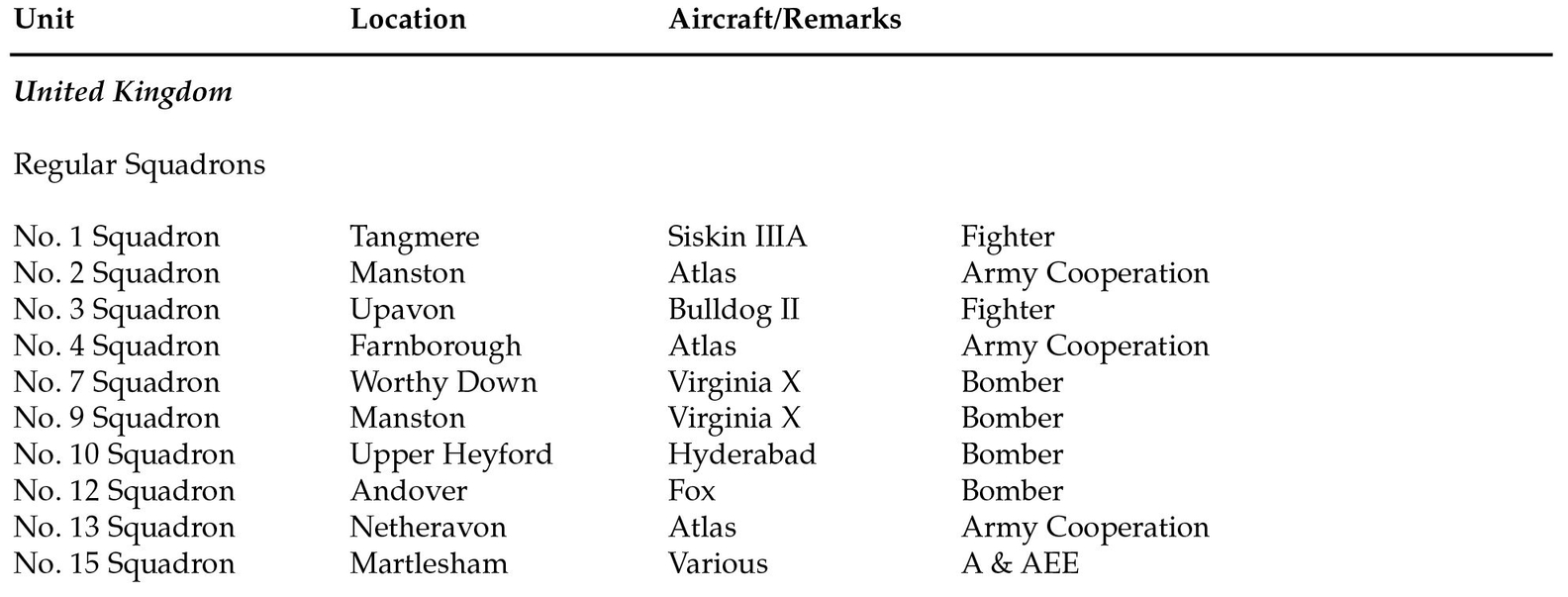

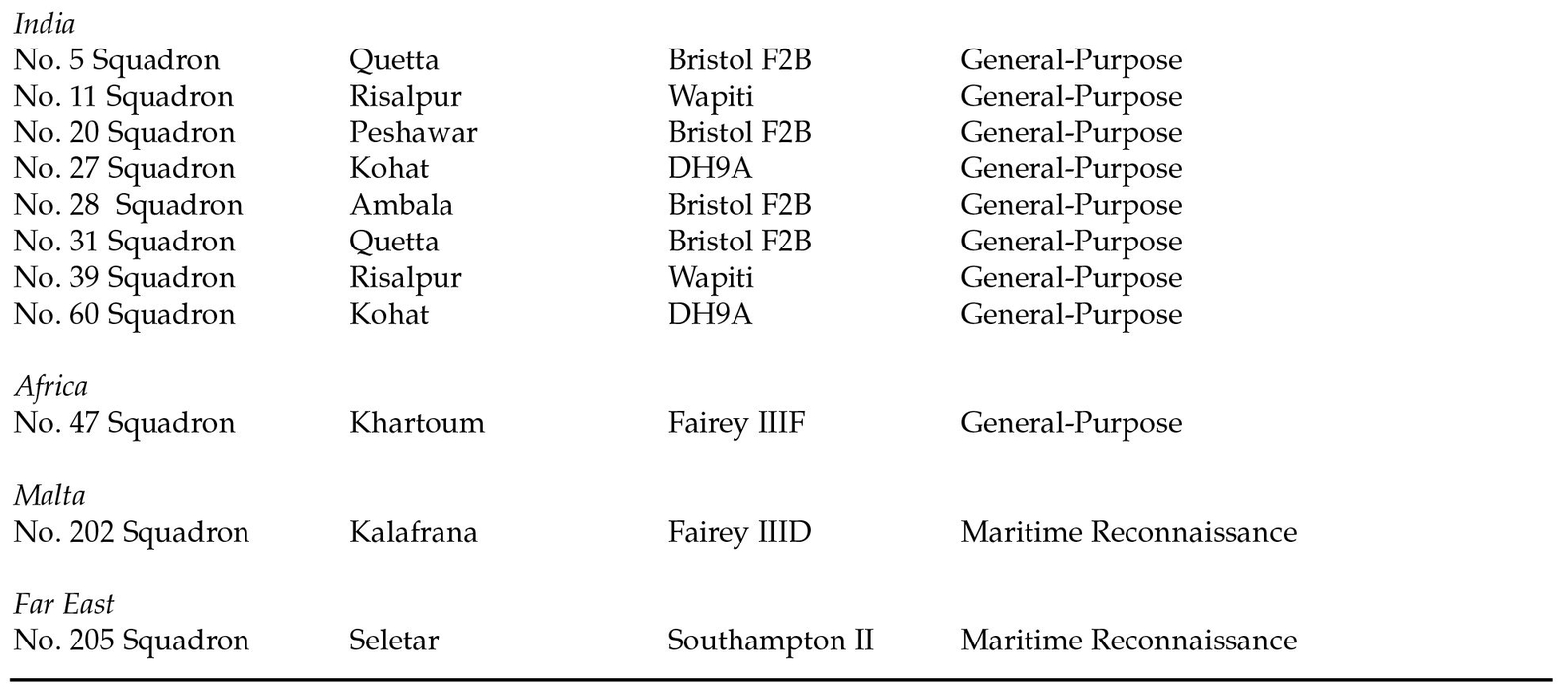

Location of Units The number of squadrons in the table below gives the picture for the whole decade. It is clear that the number of squadrons overseas remained remarkably static and that only one new theatre of operations emerged, namely the Far East. As was to be expected, the expansion programme saw the number of home-based units grow. Interestingly the latest types of aircraft did not go into operational service overseas. There was no need for fighters. The two fighter squadrons of Snipes were disbanded for that reason, and there was certainly no need for heavy bombers. What was needed was a rugged general-purpose aircraft for air control, and that is exactly what the DH9As and the Bristol Fighters were.

RAF SQUADRON DEPLOYMENT AND AIRCRAFT, 31 DECEMBER 1929

Special Reserve and Auxiliary Squadrons

Formation The purpose of the expansion plan was to provide Britain with an air force capable of meeting the threat from the air from the largest continental power within striking distance of the shores of the United Kingdom, using both purely defensive and offensive air units. To this end the number of regular air force squadrons, both fighter and bomber, was to be increased, but it was also envisaged that trained reservists could be added to the strength, giving a proportionate mix of regular to reserve squadrons that would be available in a state of emergency. Accordingly in 1925 the Air Ministry made the following announcement:

For various reasons the main part of the Home Defence Air Force must necessarily be established on a regular basis, but it has been decided that part of the new organization should consist of non-regular units. These will be divided into two classes: Special Reserve Squadrons and Auxiliary Air Force Squadrons, together forming a quarter of the total strength as at present.

There were to be seven Special Reserve squadrons and six Auxiliary squadrons. These squadrons would be akin to the Territorial units of the British Army, and were to be either city or county based. In the event only five Special Reserve squadrons were to be formed, and these were absorbed into the Auxiliary Air Force during 1936 and 1937, for over the years the number of units was to rise proportionately to the number of regular squadrons. By the outbreak of the Second World War there were to be twenty-one Auxiliary squadrons. The full strength would eventually rise to 360 officers and 2,400 airmen. A start was made in 1925, when the first HQ for two Auxiliary squadrons was formed at RAF Hendon. These were No. 600 City of London and No. 601 County of London Squadrons. The same year two Auxiliary squadrons were formed in Scotland, No. 602 City of Glasgow Squadron at Renfrew and No. 603 City of Edinburgh Squadron at Turnhouse. The first Special Reserve unit was to be No. 502 (Ulster) Squadron, formed at Aldergrove. By 1929 there were four Special Reserve squadrons and five Auxiliary Air Force squadrons in existence (see Appendix B). Of interest, perhaps, to numerologists, No. 500 (County of Kent) Squadron was not to be formed at RAF Manston until 16 March 1931.

Equipment and Personnel The equipment of these units varied. Initially they would be aircraft of First World War vintage. At its formation No. 502 (Ulster) Squadron got just two Vimy bombers, later updated to the Hyderabad. All four of the Auxiliary Air Force squadrons were initially equipped with the DH9A (Ninak), but by the end of 1929 Wapitis had replaced Ninaks in three of these units. The Horsley bomber was also pressed into service. Even though the Special Reserve squadrons were given titles suggesting local affiliation, they were commanded by a regular air force officer who was given a nucleus of regular SNCOs. The remainder of the unit strength of officers and men would come from reservists living nearby. The Auxiliary squadron, on the other hand, was raised and maintained by a county Territorial association, and manned by local personnel, with only a small cadre of regulars on strength. The squadron commander was also a reservist. These reserve units had little difficulty in attracting recruits. Flying was an enormously popular pastime, and it enabled those who had a civilian career also to indulge in it without personal cost. For the Westland senior test pilot of the 1930s, Harald Penrose, learning to fly was achieved as a reservist. Many squadrons, apart from undertaking a programme of training, had a social focus taking on the characteristics of a club. No. 601 Squadron personnel claimed, for example, that their unit was formed, not at RAF Northolt, but at White’s Club in St James, and their first commanding officer was Lord Edmond Grosvenor. Others of high social status who flew with these reserve units included Viscount Runciman, the Marquess of Clydesdale and Sir Philip Sassoon. This involvement of the famous and not-so-famous in the activities of the RAF only heightened interest in the service. Social activities aside, these units trained for war. The routine was to fly at weekends, which required a considerable degree of commitment and sacrifice among those affected, since they were already away from their families during the working week. Then there were summer camps held on major RAF airfields, with these reserve units taking part in the national Air Exercises.

University Air Squadrons

Trenchard’s Speech to the Cambridge Union On 29 April 1924 Trenchard gave a speech to the Cambridge Union. As ever, he would seize upon any chance to raise the profile of the RAF. The Annual Display was the opportunity to reach out to Royalty, Parliament, the press and the general public. Speaking to the undergraduates of Cambridge gave him the opportunity, not only to involve the brains of the nation in aviation, but hopefully to enlist officers who would be imbued with the air force spirit even before they joined. Among other things he spoke of the wastage of aircraft in peace, which was about 30 per cent per annum compared with 80 per cent per month in war. So the side that could keep re-equipping with pilots and machines would probably win. But there was no need, he said, to locate squadrons all over the Empire – as long as there were operational facilities available, units could be very mobile. He said, somewhat surprisingly, given the recent accident with the R33, which had its nose torn off in a mooring accident, that airships would be the great aircraft-carriers of the future. He then announced to his audience the creation of university air squadrons, starting with Oxford and Cambridge.

The R33 with its nose torn off!!!

Inauguration of the University Air Squadrons he idea of university air squadrons had originated at Cambridge, where a number of wartime RAF officers had gone to university to take up courses in engineering. Sir Samuel Hoare’s Personal Private Secretary was Sir Geoffrey Butler, the MP for Cambridge University in the days when there were two university seats in Parliament for Oxford and Cambridge. Trenchard enthusiastically backed the scheme, and on 1 October 1925 Cambridge University Air Unit was officially inaugurated, to be followed by Oxford. These units were to be formed in other universities, and ex-UAS pilots were to be given seniority if they subsequently joined. On the outbreak of the Second World War the Oxford squadron alone was able to provide nearly 500 officers for the RAF. These units remain, today, as a valuable source of air-minded men and women for both the RAF and the nation.

An Avro 504N of Cambridge University Air Squadron.

RAF OPERATIONS

Having established air control in Iraq, Sir John Salmond continued with his task of maintaining internal security. During this period air control was exercised in Aden, Transjordan and Palestine. In India operations designed to contain the activities of certain tribes also continued, the main difference being that in India overall control remained with the Army. What follows in this section of Chapter 3 is a narrative of events. These operations are more closely scrutinized in the next chapter.

Operations in India

Source:Air Staff Memorandum No. 48

Operations against the Abdur Rahman Khels – March to May 1925 No complete settlement had been arrived at with the Abdur Rahman Khel section of the Mahsud tribe. In December 1924 this tribal section made absurd demands, which were dismissed. This and other sub-sections of the tribe committed further offences and had to be warned that air action would be taken against them if they had not met government demands by 7 March. When no reply was received, air action commenced on 9 March. The C-in-C India had agreed that on this occasion the situation could be dealt with by the RAF alone, since the political officers had not the resources to deal with the unrest. These then were the operations that became known as ‘Pink’s War’, named after Wing Commander Pink, Officer Commanding No. 2 (India) Wing. The aircraft committed were the Bristol fighters of No. 5 Squadron, Tank, and DH9As of No. 60 Squadron, Miranshah, a total of twenty-six aircraft, forty-seven officers and 214 airmen. As operations progressed, two further flights of Bristol Fighters from No. 20 Squadron were added. The essence of the air operations was not to act routinely, so that the tribesmen never knew when aircraft might fly overhead, and they were subjected to a mixture of an air blockade, night bombing and intensive air attack. Air operations continued for a period of fifty-four days, of which forty-two were spent bombing. Altogether 2,700 hours were flown, with only one fatality. The total cost of the air operations was £75,000. All the tribes involved in the air action subsequently paid outstanding fines, and the subsequent decisions of the political officers were carried out promptly. The GOC Waziristan admitted that he could not have accomplished what the RAF had done with troops even if they had been available. At the time of these operations the weather was severe and the terrain could not have easily been traversed by ground forces.

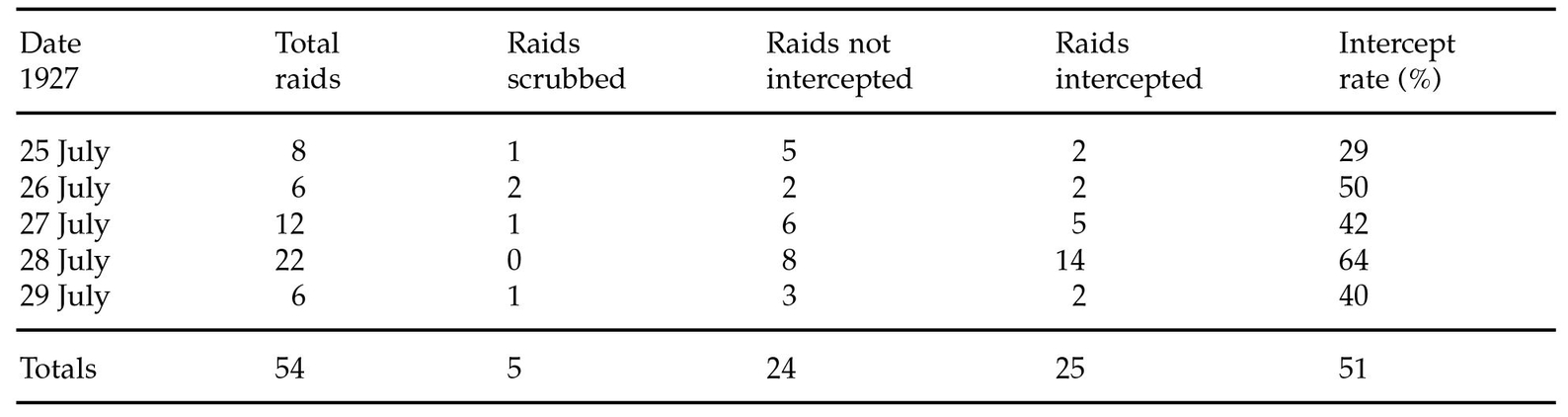

Operations against the Mohmands, 6 to 8 June 1927 On 4 June 1927 a tribal leader in the Mohmand country had collected a large body of men and was prepared to attack blockade posts on the Mohmand border. Political reports showed a concentration of between 1,000 and 2,000 men. In response a column of infantry, cavalry and armoured cars was dispatched from Peshawar to Shabkadar to attack the enemy if they should attempt to come down into the plains. In the event the tribesmen did not proceed beyond the blockade line, and for a while only a watch was maintained, but on 5 June the blockades were attacked. Bombing operations therefore commenced at 18.00 hrs on 6 June, and were maintained until 09.30 hrs on 8 June, sixty attacks having been carried out by day and night. As a result the hostile tribesmen were dispersed. RAF operations involved four squadrons less one flight per squadron. The official report states that neither officers nor men were required to be recalled from leave to carry out these operations, which took less than forty hours to achieve the objective. This may be compared with an Army operation in 1908 against the Mohmands that took one month of marching and fighting to contain a similiar situation. The report went on to say that the entire territory could be covered by aircraft in just under two hours’ flying. No casualties were sustained on either personnel or aircraft, but the enemy lost between thirty and forty killed. The total cost of the operations was put at £1,703.

Operations against the Giga and Neksan Khel, November 1928 Two sub-sections of the Mahsud tribe had committed various offences, and their defiant attitude was having an unsettling effect on the other sections of the tribe. At the beginning of November 1928 the Giga and Neksan Khels decided to stay, for the winter, in their summer quarters, some 8,000 feet above sea level, inaccessible to the supervision of the political officers. The approach of Army troops would alert the tribesmen, who could be expected to decamp into Afghanistan. No reply was received to an ultimatum, and air operations began on 15 November 1928. One squadron was involved, flying from Kohat and from a detached location at Miranshah. The small targets and the nature of the terrain precluded the use of large bomber formations and low-flying attacks. Furthermore friendly tribesmen were living in close proximity to the target locations, so accurate bombing was required. Later it was confirmed that 49 per cent of the total bombs dropped were direct hits. By 20 November the tribes concerned had accepted the full terms of the political authorities. Because of the surprise of the attack they had made no preparations to remove their property. The report claims that the operations were brought to a rapid conclusion owing to the accuracy of the bombing, which also localized the damage to houses and property of the insurgent tribesmen. The Chief Commissioner of the North-West Frontier Province made clear that the houses and property of those tribesmen who were well disposed to the government were not affected. The cost of the operations was £3,037.

Operations in Aden

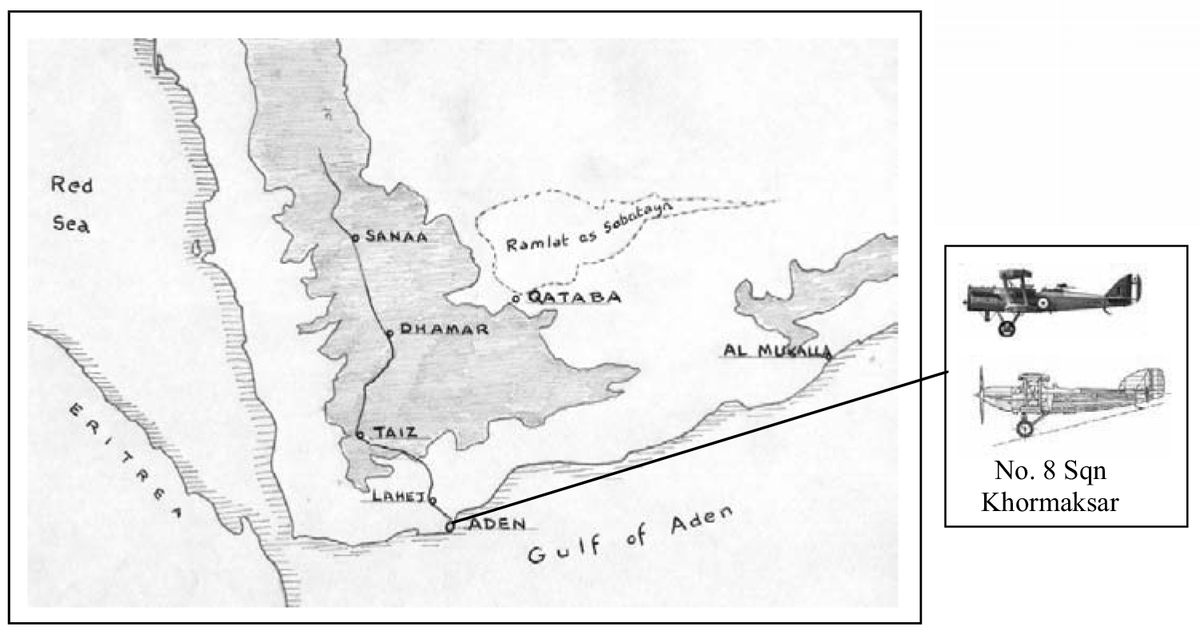

The hinterland of the Aden Protectorate resembled parts of the North-West Frontier of India. The leader of the adjoining territory, the Imam of Yemen, was steadily encroaching on the Protectorate in an area of roadless country some 100 miles from the British garrison outposts. In this hinterland were sheikhs under British protection whom the Imam had evicted, installing Zeidi garrisons in their place. In 1926 the military authorities considered using troops to restore government authority over the region. This would mean occupying Dhala, seventy miles north of the port of Aden, but it would be impossible to go beyond Dhala because of the nature of the terrain. Not only would it be necessary to use Dhala as a firm base, it would be vital to keep open lines of communications and have enough extra troops in the event of a sudden reverse. A division of troops no less, minus some artillery, was deemed necessary for this operation. Moreover operations would be restricted to the period between November and March if sickness and a lack of water was not to be experienced. The cost of these operations would have to include getting the troops in and out of Aden, and the figure was put at anything between £6 million and £10 million. The upper figure should be set against the annual air estimates for maintaining the entire Royal Air Force in 1926, which was £16 million. The Air Staff suggested sending a squadron to Aden to prevent any further encroachments by the Imam’s forces. Accordingly No. 8 Squadron became operational at Khormaksar on 27 February 1927, equipped with DH9As. In January the following year these aircraft were replaced by Fairey IIIFs.

Operations against the Zeidi Imam of Yemen, 1928 In February 1928 the territory of two sheikhs in the Aden hinterland was invaded by a Zeidi military force. Under British protection at that time were the Alawi Sheikh and the uncle of the Sheikh of Koteibi. Both of these men were captured, in spite of warnings issued to the Imam not to encroach on territory of people who had treaty relations with the British government. A decision was therefore made to bomb Qataba, the HQ of the Zeidi forces in the Dhala/Radfan area, and other Yemen towns. Forty-eight hours were given after warning notices had been dropped before air action commenced on 21 February, when No. 8 Squadron commenced operations against Qataba. During the bombing runs the aircraft came under heavy rifle fire. Operations continued on the 22nd and 23rd, after which they were suspended to give the Imam the opportunity to surrender the captured sheikhs. This did not produce the desired result, but it was not until 10 March that operations were resumed, when Maflis and troop concentrations were targeted. However, because of low cloud on the mountains, flying sorties were intermittent. Then the Governor of Taiz, no doubt with prompting from the Imam, asked the Sultan of Lahej for his principal sheikh in the Protectorate to assist in opening negotiations between the government and the Imam. The latter had agreed to the immediate release of the captured sheikhs and had asked for a truce of thirty days in order to arrive at a peaceful settlement. This would mean suspending bombing until 23 April.

OPERATIONS AGAINST THE MOHMANDS

6 – 8 JUNE 1927

Aircraft of No. 20 Sqn, No. 1 (India) Wing, ordered

by Wing Commander Walser to reinforce No. 5 Sqn.

Anti-Nejd Operations – Iraqi Theatre of Operations, November 1927.

ADEN THEATRE OF OPERATIONS.

Owing to the protracted nature of these discussions the truce was extended to 17 July. HM Government wished to see Zeidi forces being withdrawn from all areas in the hinterland that they had occupied. Dhala, the principal town, was to be evacuated by 20 June 1929 as a sign of the Imam’s good faith. Failure to comply would be met by the resumption of air operations. But instead of evacuating Dhala the garrison was reinforced. Moreover it transpired that during the period that the truce had been in place there had been active recruitment to the Imam’s cause throughout the southern Yemen. The Imam’s intention was to attack Lahej, then the Protectorate itself. And so warning messages were dropped on 21 June, and air operations resumed on the 25th. A number of Yemen towns, including Taiz and Qataba, were attacked, together with the fort of Dhala. The renewed bombing raised the morale of the Protectorate tribes, and those from Lahej, who had sought safety in Aden, felt able to return. Under air cover members of the Koteibi first thwarted the Zeidi advance then progressively forced them back on Dhala, which was recaptured on 14 July with the assistance of forces raised by the local Amir. With the Amir settled in Dhala, the local tribes settled down, when, on 1 and then 5 August, Zeidi attacks on border villages were resumed. On the approach of aircraft the Zeidi withdrew, and the Protectorate tribes were able to reoccupy the affected villages in the area on 15 August, without opposition. All the territory of the sheikhs in treaty with Britain was restored to them. Normally a permanent Army garrison could be expected to have been put in place to prevent any further encroachments, but the Zeidi knew that the Fairey IIIFs at Khormaksar could respond rapidly to any moves on their part. The cost of one RAF squadron over a five-month period was put at £8,500. It was reliably reported that the inhabitants of the Yemen capital of Sanaa, 185 miles distant from Khormaksar, had never seen or heard an aircraft, but the mere threat of bombing emptied the Bazaar and brought trade to a standstill for over a month.

Operations against the Subaihi, 1929 In the south-west corner of the Aden Protectorate certain sections of the Subaihi tribe were carrying out raids on villages and caravans in the region. These sections were warned that they must make restitution for these raids if air action was not be taken against them. When the warning was ignored, the villages occupied by the guilty tribe were bombed on 30 January 1929, and this action continued at intervals until 11 March, when the tribesmen asked to negotiate. Restitution was made in accordance with the demands of the British Resident, who reported a successful outcome on 27 March.

Operations in Iraq

Appointment of AOC Iraq, Air Vice-Marshal Sir Edward Ellington Air Vice-Marshal Sir Edward Ellington was appointed Air Officer Commanding Iraq on 19 November 1926. He had previously been AOC Middle East and AOC India. Sir Edward had had a most unusual career, having spent it almost entirely as a staff officer. He started life in the artillery before going into aeronautics in 1913, then back to the cavalry in 1915, before returning finally to the air service in 1917. His only active operational period of air force command was not as a junior or senior officer, but as an Air officer.

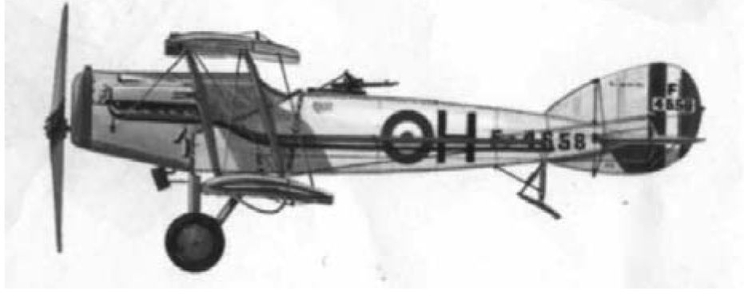

Operations against Mahmud Sheikh Mahmud, the self-proclaimed ‘King of Kurdistan’, had retreated to Persia (Iran) following combined action by RAF aircraft and Levy troops, and his forces had remained inactive throughout the winter of 1925 and 1926. But in the spring of 1926 he had his men infiltrate some tribal villages. During March and April the weather was against British attempts to expel the rebels, and it was not until June that intensive air action became possible. RAF units that went into action were Nos 1 and 30 Squadrons. No. 1 Squadron had Sopwith Snipes detached to Sulaimania, and these aircraft were successful in dispersing Mahmud’s forces. A detachment of these aircraft was left at Sulaimania to prevent any recurrence of trouble, but in September 1927 the parent squadron was disbanded and re-formed as a fighter squadron in the United Kingdom. Aircraft of the disbanded squadron were disposed of locally and the personnel posted to other RAF units in Iraq to complete their overseas tours. There simply was not a need for fighters to act in an escort role since there was no air opposition in the Middle East at this time. The DH9As of No. 30 Squadron, Kirkuk, were used in the same operation. When one of these Ninaks was forced down with engine trouble on 14 June, the crew was captured and the retreating rebels took them to their usual refuge. However, not only was the sheikh persuaded to surrender his captives in October, he also agreed to the terms of the political officer and caused no further trouble for three years.

Sopwith Snipe.

Operations against Sheikh Ahmad With Mahmud quiescent for a while, the government took the opportunity to reinforce another area of possible unrest in Central Kurdistan. This time it was Sheikh Ahmad, who had fought against foreign administrative control since the end of the First World War. In 1926 the territory, which he regarded as his area of influence, came under the nominal control of the Iraqi government. In 1927 punitive action taken by a force of Iraq Levies, which occupied Barzan, and Ahmad and his immediate entourage took to the hills. The Bristol Fighters of No. 6 Squadron and one flight of No. 55 Squadron, with its Ninaks, ensured government success in expelling Ahmad.

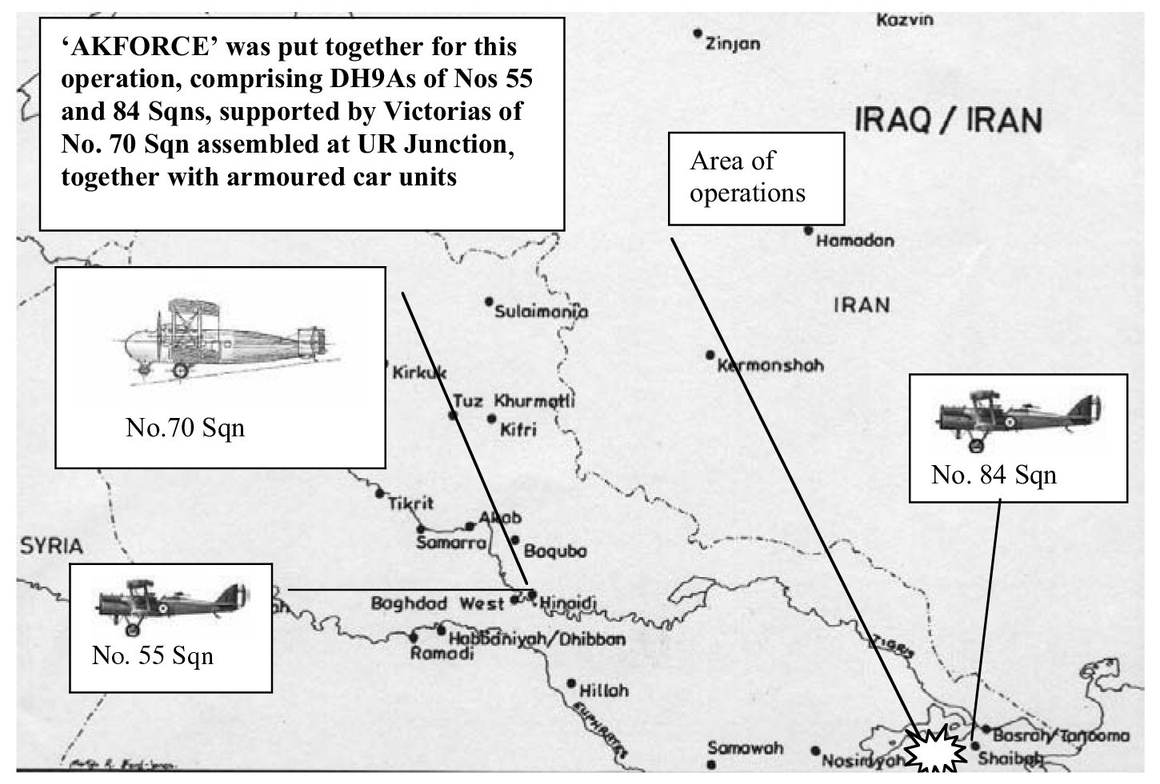

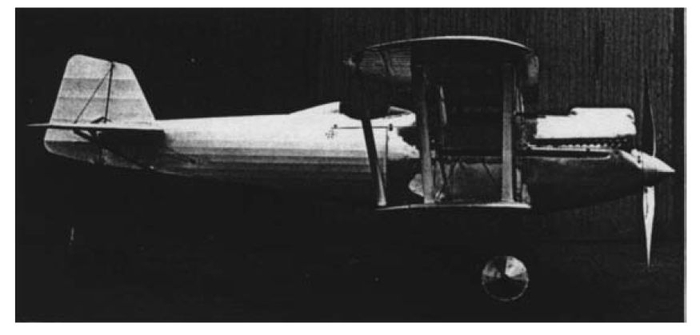

The Anti-Nejd Operations, 1927 At this time troubles repeatedly arose when tribes competed for supremacy over other tribes. Prominent among Arab leaders was Ibn Saud from the territory bordering Kuwait known as the Nejd. There had been inter-tribal conflict since the immediate post-war period, but when these troubles involved the authorities action had to be taken. On the night of 5/6 November 1927 a party of Mutair tribesmen attacked a post of the newly created Iraqi Camel Corps. Having killed all but one policeman, the assailants fled into the Nejd, leaving the injured survivor to raise the alarm. When attacks across the border continued, it became clear that Ibn Saud was either unwilling or unable to control his men. Since he had displayed personal hostility to King Feisal, it was probable that he was not prepared to stop the incursions. Accordingly he was given six weeks to restrain his men if he was to avoid a blockade of the Nejd and Hasa coasts and air attacks. The use of force was authorized on 3 January 1928. While awaiting the reaction of Ibn Saud the authorities took the precaution of forming an advanced headquarters known as ‘Akforce’. On 8 February, elements of Nos 55, 84 and 70 Squadrons assembled at Ur Junction, together with armoured car units. At Akforce HQ the Victoria IIIs of No. 70 Squadron were on hand for reinforcement and supply. Meanwhile advanced operational bases were established at Busaiya and Sulman. Warning notices went out on 11 January to the effect that any rebel tribesmen found in the proscribed area would be bombed without warning. At first these warnings seemed to be having the desired effect, but when it became evident that there was not compliance, warning bombs were dropped around the tribesmen’s encampments to avoid casualties. Then, on 27 January, an Akwhan force of 300 men mounted raids on Kuwait tribes seventy miles south-west of Basra. The next day RAF aircraft joined in the pursuit of the raiders, making contact with a large party fifteen miles north-east of Hafar. Accurate rifle fire succeeded in bringing down one aircraft, and it was usual in these circumstances for a friendly crew to attempt to retrieve the crew of an aircraft that had been forced down and rescue them. The following day another party of tribesmen was attacked eight miles west of Hafar. Again one aircraft was forced down by rounds that penetrated the radiator. The Ninak was flown by a lone pilot who was only 400 yards from the tribesmen when his aircraft came to a halt. In spite of intense rifle fire that was directed at the Ninak, Flight Lieutenant J.F.T. Barrett DFC, piloting another DH9A, landed close by and rescued his colleague. By February the number of rebel tribesmen involved was estimated to be in excess of 50,000, but individual raiding parties usually comprised only 4,000 men, and permission was given to use bases in Kuwait to repel the incursions. Akforce was reinforced by a flight of No. 30 Squadron and a section of armoured cars from Hinaidi. At Heliopolis in Egypt one flight of No. 216 Squadron (Victorias) was put on stand-by. Patrolling continued throughout March and April, but air action declined as the tribesmen progressively retreated inland. By 3 June Akforce could be stood down, and all air units were returned to their normal bases and duties. Just before the stand-down an attack was made on the remote island of Gubbah on the Hammar Lake, the stronghold of one rebel sheikh. The Ninaks of No. 84 Squadron bombed the banking that surrounded the island, and breached it, which caused flooding, and the rebels were forced out of their refuge. Ibn Saud then gave a formal written undertaking to restrain his tribes thereafter.

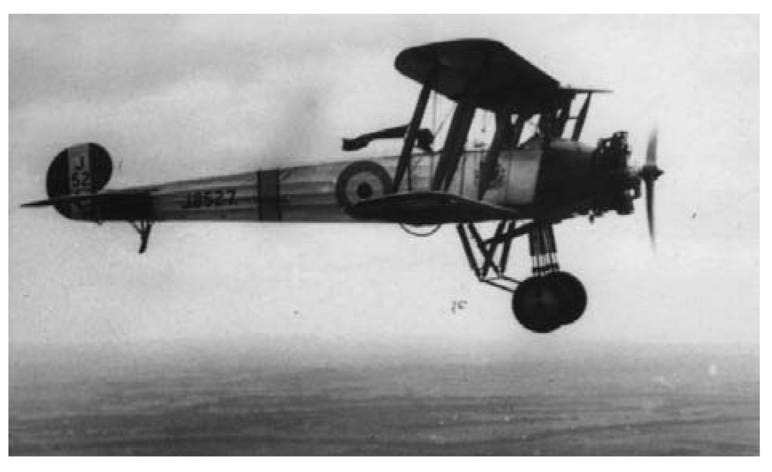

A Ninak of No. 84 Squadron, the unit that attacked the island of Gubbah on the Hammar Lake.

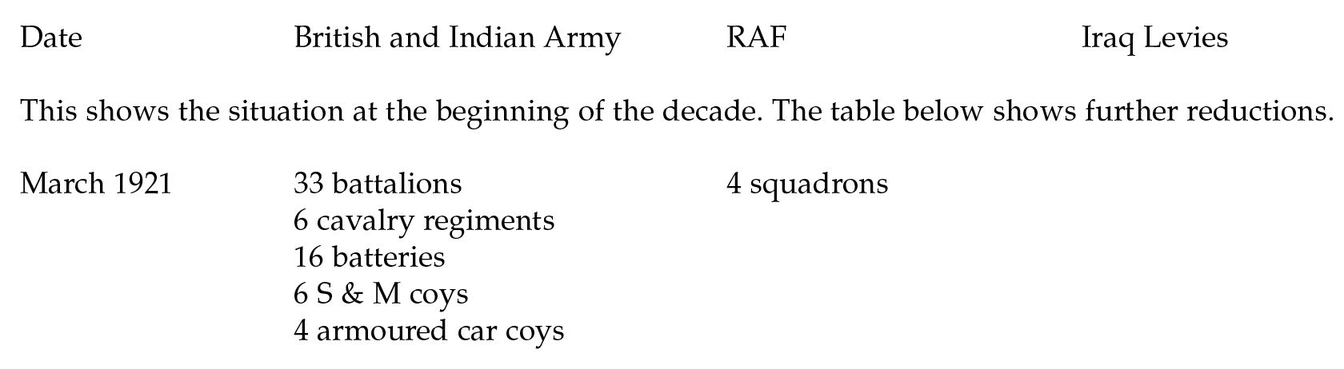

Reduction in the Iraqi Garrison Continued success on the part of government forces in Iraq made possible further reductions in the military garrison, aircraft replacing ground troops, which had always been the intention. The figures were:

REDUCTIONS IN MILITARY GARRISON IN IRAQ (COMBATANT UNITS ONLY)

British Somaliland

In the opinion of the Air Staff, the Mijjertein Incident of 1927 is an illustration of how the morale effect of air power can gain an objective without casualties to either side. The Italian government had ordered military operations to be taken against the Mijjertein tribe inhabiting the border region between Italian and British Somaliland, resulting in this tribe crossing the border to escape the attentions of the Italians. When bombs were carried forward to an advanced landing ground by the RAF, the word got through to the sultan of the tribe, who was persuaded to surrender rather than face air action.

The Kabul Rescue, December 1928.

The Kabul Rescue

(See the history of No. 60 Squadron in Chapter 4 for a detailed account of this operation.)

At the end of 1928 a force of 1,000 rebels, led by an insurgent named Habibullah, captured forts to the north-west of the capital of Afghanistan, Kabul. His men captured stocks of rifles and ammunition and went on to engage King Amanullah’s attacking troops. The problem for Britain was that this action threatened the British Legation, which was then cut off from the capital, and the British Commissioner radioed for help. Air Vice-Marshal Sir Geoffrey Salmond, the AOC India, decided to attempt an evacuation of the Legation by air. This was by 1928 standards a hazardous operation that would involve flying from Peshawar over 10,000 ft mountains covered in cloud. Salmond first sent in unarmed DH9As with leaflets to warn of the airlift. Then, on 23 December, a Wapiti with a radio went as a pathfinder through the Khyber Pass to check that Victoria transports could land at Sherpur aerodrome. Subsequently a Victoria of No. 70 Squadron flew in to bring out twenty-three women and children, their baggage being collected by DH9As. On Christmas Day a Victoria, a Wapiti and eleven DH9As took out another twenty-eight persons. By New Year’s Day 586 people had been rescued, including the Afghan Royal Family, together with 24,193 lb of luggage. More than 28,000 miles were flown in some of the worst weather on record.

Shanghai Defence Force

The Chanak crisis had shown how a distant theatre of operations could be reinforced with RAF squadrons using aircraft- or seaplane-carriers. In early 1927 the RAF was again called upon, this time in China, as part of a tri-service force. The city of Shanghai had been threatened with invasion and occupation by Cantonese Chinese revolutionaries led by Dr Sun Yat Sen. Hankow, some 400 miles up the Yangtze river, had been overrun, and attacks upon Nanking had taken place. HMG now feared that British lives and property in Shanghai would come under threat. The air element in the newly created ‘Shanghai Defence Force’ was titled ‘Royal Air Force China’, and was commanded by Group Captain E.D.M. Robertson DFC. Originally Robertson had air sections that were aboard HMS Hermes based in China and the ex-UK seaplane-carriers Argus, Vindictive, Enterprise and Tamar. To these ship-borne aircraft would be added the Bristol F2Bs of No. 2 Squadron, RAF Manston, commanded by Squadron Leader W. Sowrey DFC, AFC. No. 2 Squadron was shipped aboard SS Neuralia on 20 April 1927, and arrived in Shanghai on 30 May.

The problem confronting the air commander was the lack of any suitable landing ground, but there was a possibility of finding one on the Kowloon peninsula. A recreation ground alongside the Shanghai racecourse provided a 400 yd landing run parallel to the racecourse grandstands, and bamboo hangars were hastily erected by local Chinese contractors. (This was eventually to become RAF Kai Tak.) By the time the aircraft had arrived, Shanghai was already being threatened with mob violence from its Chinese population of more than two million. The RAF strength was equivalent to five squadrons, and they maintained regular air patrols around the settlement until Nationalist Chinese forces assumed control of the Shanghai area, permitting the return of No. 2 Squadron to Manston in October. It was believed that the presence of RAF aircraft in the Settlement prevented the outrages that had occurred in Nanking and Hankow. One positive outcome was the preparation of the site at Kai Tak by an RAF rear party, for a permanent airfield, which was to become an RAF station.

Singapore

The Threat Another theatre of operations that had exercised the minds of Trenchard and the Air Staff was Singapore. The staff at the Admiralty were intent upon converting the base into a ‘Gibraltar’ of the Far East, and proposed siting 15 in. naval guns to protect the port from the sea. It was reasoned that the dense jungle of the hinterland would make an attack from the landward side, that is down the Malay peninsula, inconceivable. Japan, potentially the largest naval power in the Far East, could be expected to attack from the sea. The lessons of Aqaba during the First World War seemed not to be have been learned. There the Turkish garrison had its main armament facing out to sea in the belief that no attacking force could come out of an impassable desert, which is precisely what T.E. Lawrence did at the head of a force of Arab tribesmen. He did what the enemy least suspected, which gave him the element of surprise. When the Japanese took Singapore in 1942 they attacked from the landward side.

Guns v.Aircraft

In considering how best to defend Singapore, His Majesty’s Government was preoccupied with managing the General Strike, and left it to the services to sort out the matter between them. Eight 15 in. coastal guns were favoured by the Navy and Army staffs, while Trenchard proposed a force of torpedo-bombers supported by fighters and reconnaissance aircraft. With an operational radius of 150 miles, torpedo-bombers could intercept battleships way beyond the twenty-mile range of coastal artillery. Beatty was on his sick bed at the time, and conceded that as a first stage only three guns would be installed, pending an investigation into the relative merits of guns and aircraft. The balance of five guns might be set aside in favour of aircraft. The downside for the RAF, so to speak, would be the need for a chain of aerodromes/landing grounds from Calcutta to Singapore for reinforcement, and the development of torpedo-bombers capable of filling a dual role of coastal defence and frontier warfare. Subject to these provisos it was agreed to delay implementation of the second stage, and on 3 August 1926 the Cabinet accepted this compromise. But a long delay ensued. Firstly, the War Office could not decide on the type and mounting of the 15 in. guns, and secondly, Sir Laming Worthington-Evans, the War Minister in 1928, admitted that trials with heavy guns at Portsmouth and in Malta gave cause for ‘reasonable doubt’, and so installation was delayed for a year. Trenchard seized the opportunity to suggest that aircraft might fill the gap until the problems with the guns were sorted out. The Committee of Imperial Defence agreed.

THE SCHNEIDER TROPHY RACES

The RAF’s involvement in the Schneider Trophy races during the inter-war years is well documented, and it is certain that the development of airframes and engines to meet the needs of this contest contributed to the introduction of the Merlin-powered Spitfire in 1936. The Trophy was the idea of the armaments magnate Jacques Schneider, and was awarded to the winner of an international competition between seaplanes, based on speed and endurance. Should any national team win on three successive occasions that country would win the trophy outright. The French were the first winners in 1913 with a Derpudussin that flew at 45 mph over a distance of 172.5 miles near Monaco. In 1914 the British won with a Sopwith seaplane at a speed of 86.78 mph.

The races were suspended during the hostilities of the First World War, and when they were resumed the distance was extended to more than 200 miles. The winners in succeeding years were Italy in 1920, 1921 and 1926, Great Britain in 1922 and the USA in 1923 and 1925.

The RAFs involvement in the races The 1926 race was won by Major Mario de Bernadi at an average speed of 246.5 mph. This Italian success could be put down to official government backing, and there was a growing recognition that the competition was not something for private sporting individuals, if only because of the expense involved, and the British had not entered a team that year. Those interested in the Schneider competition who were present at a meeting on 19 March included the Air Ministry, the Royal Aero Club and the Society of British Aircraft Constructors. There was unanimous agreement that there should not be a British team entered in 1926, but since there had not been a competition in 1924 and the USA had won in 1923 and 1925 the Americans could win the trophy outright. Although the Italian success in 1926 effectively scuppered the USA, it jolted Britain into the realization that a more positive approach to these races was essential if the trophy was not to be lost to another country by default. The British Air Minister, Sir Samuel Hoare, took the view that the British government should defray the cost of the machines and that the RAF might take over the training of pilots to fly them. The Air Estimates for the year 1926/7 accordingly included the sum of £100,000 with Treasury approval.

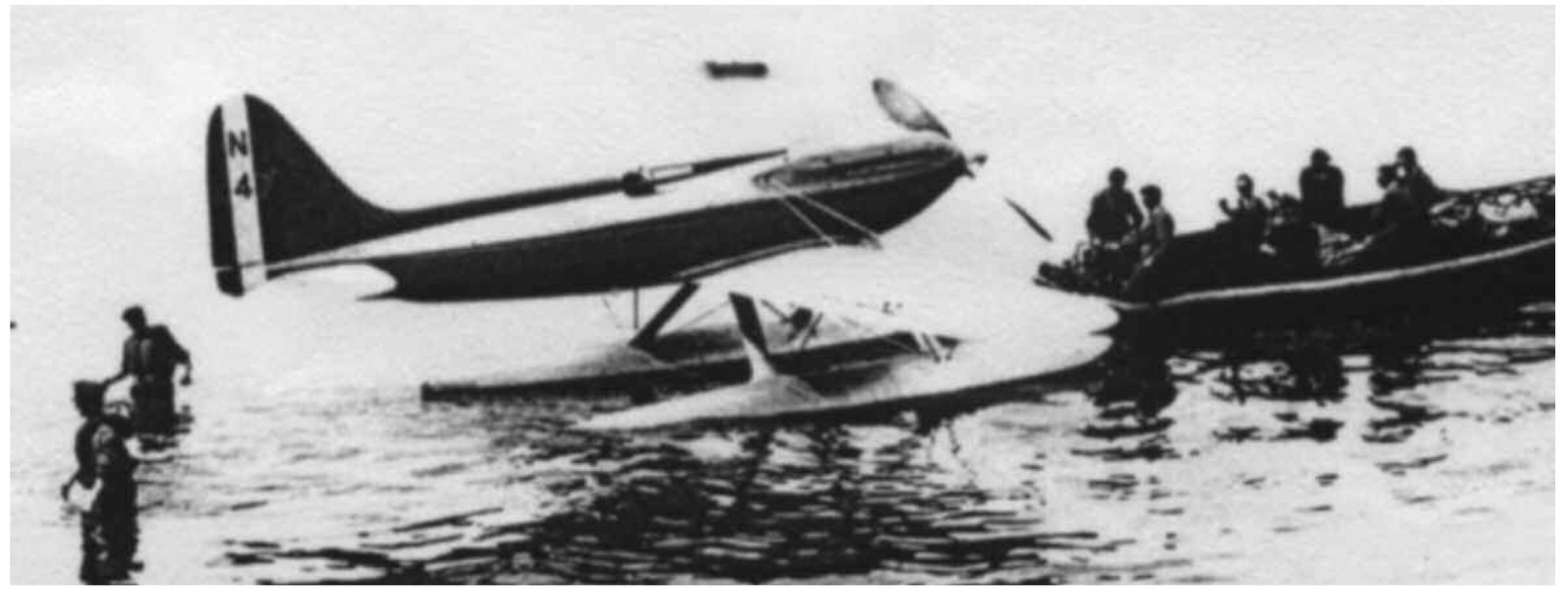

The 1927 Contest

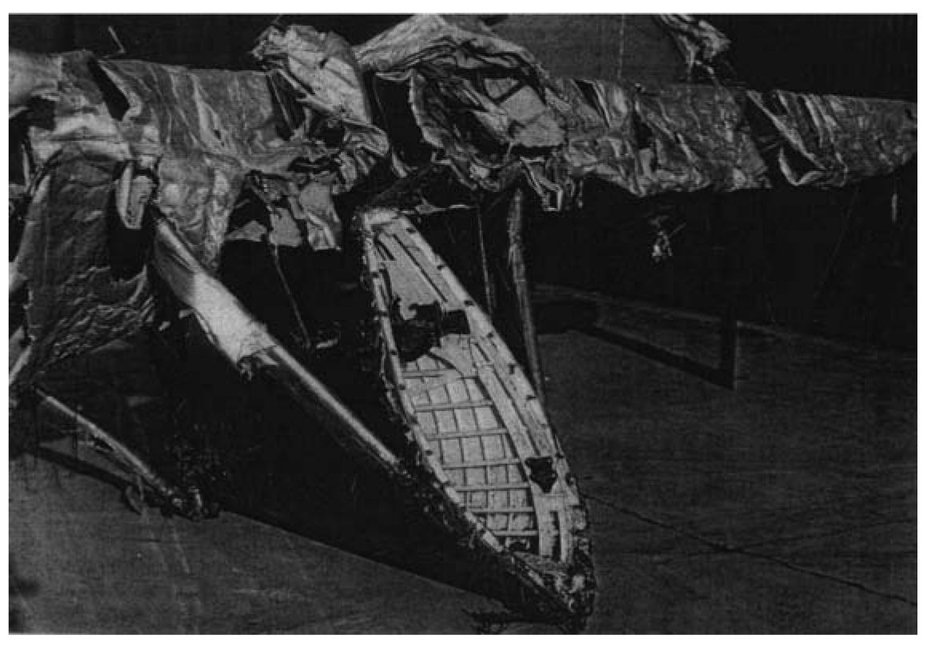

The RAF team went off to Venice for the 1927 competition with two Supermarine S5s and three Gloster biplanes. The race was to take place over the Lido, the long island forming a barrier between the Lagoon of Venice and the Adriatic. At the mid-point of the Lagoon was the Excelsior Palace Hotel, headquarters of the British team. The contest was to be along the 13.5 nautical miles of the Lido bathing beaches. The US Navy Department had to withdraw its entrant, Lieutenant Alford, holder of the 1923 world record of 266.6 mph, since he could not complete the tests necessary to qualify for entry; and this left only Britain and Italy in the race. Having arrived earlier than expected, the British seaplanes had been erected and were ready for test. The Crusader was slower than the other machines and the engine was susceptible to cutting out, so it was designated the test aircraft. On 11 September Flying Officer H.M. Schofield took the Crusader out and made a long take-off run, but his aircraft was no sooner clear of the water than it half-rolled and dived into the lagoon upside-down, tearing off a float and holing the fuselage, so that water rushed in with such force that Schofield was ejected. When he was rescued it was found that virtually all his clothes had been ripped from his body. When the aircraft was recovered a week later from the bed of the lagoon, it was discovered that the control wires to the ailerons had been crossed so that they had the opposite movement to that intended. One of the essential pre-flight checks carried out by a pilot is to observe the movements of all flying surfaces in response to movements of the controls, so clearly this had been forgotten in the excitement. But the workmen responsible for assembling the aircraft had not done their job, nor had those responsible for checking the work prior to the flight, with nearly fatal consequences.

On Friday 23 June there were the navigation and mooring tests. The race, due to take place on the Sunday, was postponed because of bad weather, and it was not until 12.30 hrs on Monday 26 September that the three British machines, followed by the three Italian racers, moved down the canal. Flight Lieutenant Kinkead was at the controls of the Gloster IVB biplane racer, and Flight Lieutenants Webster and Worsley flew the Supermarine S5s. The Italian team was led by the previous world record holder, Major de Bernadi, in a Macchi M.52, with team mates Lieutenants Guazzetti and Ferrarin. The Italians suffered bad luck throughout the contest. Initially de Bernadi drew roars of applause from the crowd as he pulled out of a dive with a zooming turn, but he was seen shortly afterwards rolling in the swell, as his engine had failed with a broken piston. The last of the Italians to start was Ferrarin, but his aircraft also suffered engine failure, through a broken piston. The last surviving Italian, Guazzetti, was meanwhile being lapped by Webster with a first-lap average speed of 280 mph. Kinkead in the Gloster had also to abandon the race when his seaplane suffered a spinner failure and a strip of metal wrapped itself round one of the propellers, which set up tremendous vibration. Then, on his fifth lap, Guazzetti was nearly blinded by leaking petrol and had to alight on the lagoon. When the spectators could see that it was left to the two S5s to battle it out the crowd began to melt away. Webster’s seaplane had a 900 hp geared Napier Lion engine. The original engine had been a 450 hp unit, which had been uprated for racing, and it gave Webster the edge over Worsley with his fixed-drive engine. Webster attained an average speed of 281.65 mph, beating the existing world speed record by a mere 3 mph.

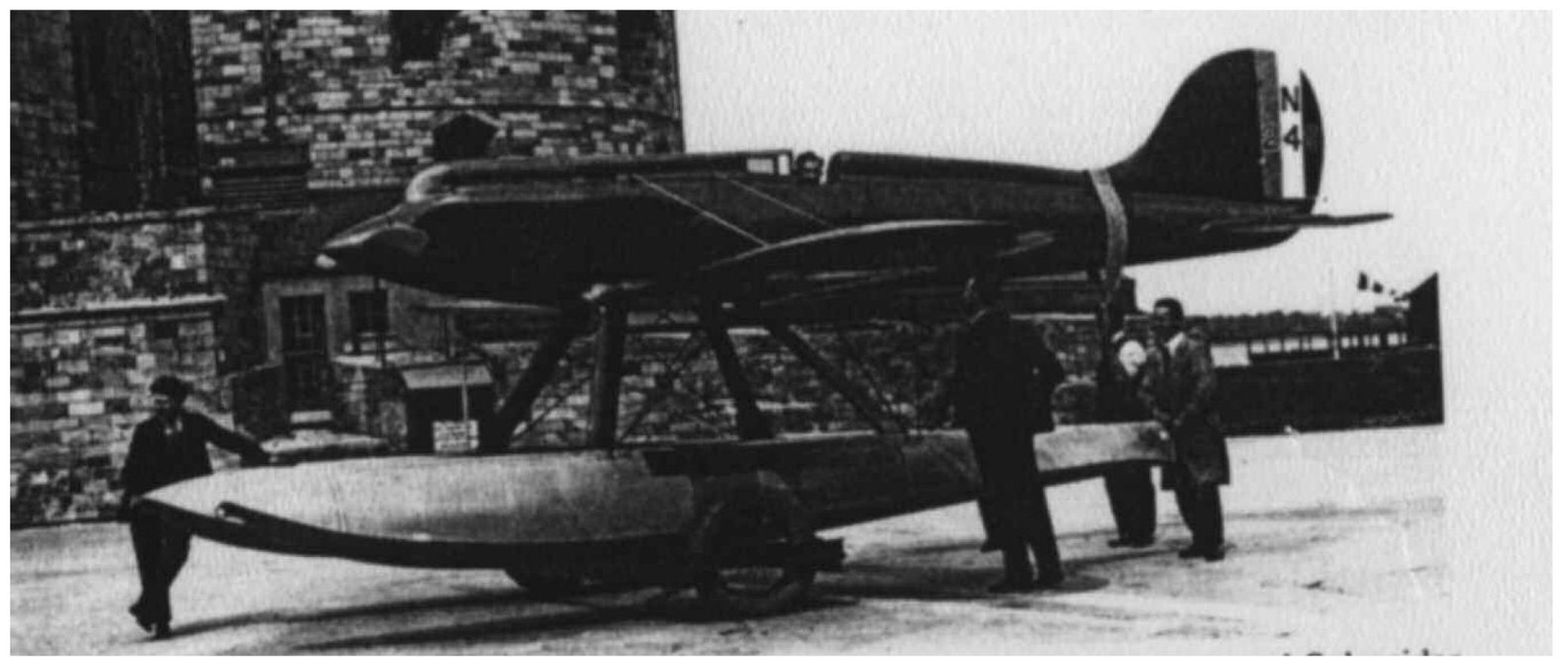

The 1929 Contest

The aircraft and the team There being no contest in 1928, the 11th Schneider Trophy Competition was staged at Calshot in September 1929, it being the custom that the venue for each contest would be determined by the winner of the previous one, i.e. Britain in Venice in 1927. It was in 1928, also, that the race’s promoter, Jacques Schneider, died. He too was a pilot, having been taught by no less than Louis Blériot. On 12 August the press were invited down to Calshot to view the British entry. The Gloster IVB and Supermarine 5s of the 1927 competition were designated training aircraft, and could be compared with the two S6s and the Gloster VI of the 1929 entry. The Gloster VI was painted in gold, and the Supermarine S6s in blue and silver. It was plain to see the improvements that Mitchell of Supermarine and Folland of Gloster had made to their seaplanes. The S6s had Rolls-Royce engines and the radiators were built into the wings, flush with the wing surfaces. The RAF had formed a High Speed Flight, commanded since January 1929 by 35-year-old Squadron Leader A.H. Orlebar AFC. His team comprised Flight Lieutenant D. D’Arcy Greig DFC, AFC, Flight Lieutenant H. Stainforth and Flying Officers Atcherly and Waghorn. The 30-year-old Stainforth, with Atcherly and Waghorn, both 25 years old, were Wittering-based pilots. The two younger men had both been members of the 1927 Hendon Aerobatic Display team commanded by D’Arcy Greig. The latter had become famous for baling out of a Grebe fighter that was in an uncontrollable spin and for leading inverted Genet Moths in formation during the 1927 Display.

Supermarine S6 No. 247, one of two entered for the 1929 Schneider Trophy Competition.

Pre-Race problems

On 22 August Italy suffered a setback with the death of Lieutenant Motta at his training base in Italy when he crashed in the tandem-engined Savoia Marchetti low-wing tail-boom seaplane. The team also lost the Fiat C.29, but without killing the pilot. So the Italians asked for a postponement, but according to the rules, this could only be granted on account of bad weather. The Italians believed that there was a precedent when the Americans had postponed the race in 1926 because the Italians had not arrived in the USA in time for the preliminaries. The race did not start until November, and then the Italians won. Should Britain show the same generosity? France had withdrawn and the USA was having trouble with its Mercury monoplane. The RAF team was also not without its problems. The liner Mauritania almost swamped one of the Supermarine S6s as it steamed up Southampton Water. Strong winds prevented practice flights with the training machines, and Squadron Leader Orlebar had to be towed in when there was a petrol feed problem with the Gloster VI. On 28 August General Balbo let the world’s press know that Italy would enter the race as a gesture of chivalrous sportsmanship. The death of Lieutenant Motta had not only deprived Italy of its best pilot, claimed Balbo, but also the machine and engine perfected for the race. One of the two Italian seaplanes that had arrived in London had not even been in the water, and when General Balbo arrived in England he was worried about the amount of casual shipping that crossed the Spithead race course. By the time that the five Italian machines had arrived, there was still trouble with the Supermarine S6s, which had water getting into the floats. When the practice flying did commence with a vengeance, it was clear that the Italians were relying on two scarlet Macchis. The British team, meanwhile, was still having trouble with fuel starvation, and although Stainforth and D’Arcy Greig agreed that the Gloster VI handled well, during a last test-flight on Thursday before the race the sound of the machine misfiring over Calshot meant only one thing. There would not be a Gloster VI in the competition.

The Gloster VI entered for the 1929 Schneider Trophy Competition.

The Race

On Friday 6 September the qualifying trials took place. The competitors had to take off, fly a short course, alight, taxi between two buoys, take off again to fly the short course and alight a second time. Each aircraft had then to be moored for six hours without sinking. All the aircraft passed, and on the morning of Saturday 7 September the machines were taken to the start line. Privileged guests watched from the lawns of the Royal Yacht Squadron, crowds were gathering on the Cowes waterfront and RAF patrol boats were busy keeping small craft out of the contest area. At exactly 2 p.m. the starting gun fired, and Waghorn was away in the S6. On return to Cowes there was speculation about the speed on the first lap, and this proved to be 324 mph, 6 mph above the world speed record and 43 mph faster than the S5 in 1927. As Warrant Officer Dal Molin took off in the Macchi M52 bis, Waghorn overtook him on the Cowes – Ryde leg. Then D’Arcy Greig followed in the S5. Lieutenant Cadringher in one of the new Macchi M67s was next, but flew wide at Cowes, blinded by fumes that restricted his view through the small windshield. As he passed Southsea, witnesses saw a streaming exhaust. The Italian then crossed the mouth of Southampton Water, barely cleared the hill above Castle Point, then dived out of view to land safely. Meanwhile Waghorn was completing succeeding laps without difficulty, followed by Warrant Officer Dal Molin and D’Arcy Greig in the S5. The swell had increased when the gun went for Atcherley, causing his S6 to porpoise, but he then took off smoothly. Waghorn had been briefed to nurse his engine to complete the distance. Atcherley’s first lap was at a speed of only 302 mph, and when he lost his goggles he missed his turning point, resulting in his disqualification. The last to take off was Tenente Monte, but having achieved a first-lap speed of 301 mph, he was forced down off Hayling Island with a broken oil pipe, which caused bad scalds to his arms and legs. Waghorn lost count of the number of laps that he had completed, and shortly after flashing past the winning post he ran out of fuel. It was not until the RAF tender reached him that he was relieved to learn that he had been attempting to fly an extra lap. He was the winner, followed by D’Arcy Greig in the S5 and WO Dal Molin flying the slowest of the Italian machines. Thus Britain had won the Trophy on two consecutive occasions. Everything depended upon a third win for Britain to retain the Trophy in perpetuity.

Other Matters

The King, the Prime Minister and other members of the government had every reason to be pleased with the RAF’s second win in the Schneider contest. When the news of the 1927 win came through, Sir Samuel Hoare, the Air Minister, happened to be Minister-in-Attendance on the King at Balmoral. ‘The King realized that his Air Force had gained considerable prestige by the result’, Hoare recalled. He wanted to know whether or not the training and the high-speed flight had affected the pilots’ health, and was interested to hear that they had given up alcohol and tobacco. The Prime Minister, who had to justify all public expenditure on the part of his government, was pleased. Mr Ramsay MacDonald was present with his Air Minister, Lord Thomson, and a ship had been chartered for the 1929 race from which the distinguished guests could watch. At an after-dinner speech he pledged that Britain would enter a team in the next race, but this was not due until 1931, and the economic situation at that time would mean that pledges made in 1929 could not be honoured by the government. Another famous man who was present at the 1929 race, who had achieved fame but later sought anonymity, was Aircraftman Shaw (Lawrence of Arabia), who was closely concerned with the safety of the race course, through his work in developing high-speed launches at Calshot.

Postscript

The detailed arrangements made for RAF personnel to view the Schneider Trophy race of 1929 make interesting reading, and can be found at Appendix J. RAF Gosport was going to bulge at the seams, being prepared to accept 500 officers and airmen as spectators, not to mention a maximum of 170 aircraft parked on the airfield for those travelling to the event by air. Throw in an Army fort that would act as a viewing vantage point for the race, a local golf course for the relaxation of visiting officers and arrangements for car parking at the princely fee of 10s (50p), and the reader will see that great care was taken to see that the home team would be well supported.

The Supermarine S5 of the 1927 Schneider Trophy

Competition, Venice.

THE RAF DISPLAY

The RAF Pageant, or Display, as it had been retitled, continued to attract huge crowds each July, come rain or shine. The display could be divided into the following elements:

- The flying displays, including aerobatic performances

- A means of introducing new types to the public

- The provision of a ground display to permit the public to take a close look

- The focus of annual training by aircrews

The 1926 Display

The 1926 Display was held on Saturday 3 July. It was a hot day with brilliant sunshine and some cumulus cloud. In spite of this being the last day of the Henley Regatta, the Display still attracted a crowd of 120,000, and the ladies were turned out in their finery. The events were longer and fewer than in the previous year. The flying displays featured not only some of the latest aircraft but the names of pilots who were to succeed to Air rank – Atcherly, Slessor, Harris and Longmore – as well as those who had already made a name for themselves, such as Squadron Leader Collishaw, the fighter ace who had commanded No. 47 Squadron in South Russia during the Russian Civil War. Some of the aircraft that featured in this display were the Bristol F2B Fighter, the Gamecock and Grebe, Virginia and DH9A. The Gloster Grebes had R/T, which permitted Squadron Leader Peck to announce the various manoeuvres to his pilots.

Bristol Fighter.

Grebe.

Virginia.

Gamecock.

DH9A.

Avro Avenger.

Fairey Firefly.

Fairey Fox.

Gloster Gorcock.

Hawker Hornbill.

Hawker Heron.

But where the display was different from its predecessors was in the preponderance of aircraft designed and built since 1918 in the Experimental Aircraft Park. These are shown on this page, and the more aerodynamic qualities stand out and can be contrasted with the unorthodox appearance of the Westland Pterodactyl, which did not enter RAF service, and the Cierva Autogyro. The Hawker Heron was still undergoing trials at Martlesham Heath and had to be flown to Hendon specially for the Display.

In the flying display the Armstrong Whitworth Atlas, Army Cooperation aircraft, was shown off for the first time. The Fairey Fox, with its American Curtiss engine, thrilled the crowd by screaming like a banshee as it pulled out of a dive. This was a beautifully clean aeroplane, the radiators being buried in the wings. These aircraft were all faster than the Bristol Fighter, yet the improvement in performance was not spectacular. The new Hawker Horsley was also present. It was designed by Sydney Camm, Hawker’s new designer, who was to go on to design the famous Hurricane.

The 1927 Display

In stark contrast to 1926, the Display of 1927 was a day of drizzle and a gusty north-west wind. But this annual event had become so firmly established in the public’s mind that the crowds still turned up in their thousands to fill the newly erected 3,000-seat grandstand and the car parks. At 3 p.m. the King and Queen arrived, accompanied by the King of Spain, the Duke of York and the exiled King and Queen of Greece, together with the Air Minister, Sir Samuel Hoare, Sir Hugh Trenchard and Sir Philip Sassoon. In addition to the usual flying display, six parachutists dropped from three Vickers Vimys, a Kite balloon was destroyed, though not before a stuffed dummy, who went by the name of ‘Major Sandbag’, descended from it by parachute, and there was always a ‘set-piece’ battle as the grand finale, involving a fort or some other structure that could be demolished in a blaze of pyrotechnics. In 1927 a fort was attacked with bombs and machine-gun fire, and Fairey Foxes beat off the attacking forces while troop carriers flew in to rescue the defenders. A close-formation aerobatics display was led by Flight Lieutenant D’Arcy Greig, the chief instructor of the Central Flying School, Wittering, and also a member of the British team in the Schneider Trophy races. His formation of scarlet-topped Genet-powered de Havilland Moths, flown by his assistant instructors, performed formation-flying inverted. Apart from the difference in speeds then and now, very little has been added to the quality of aerobatic displays over the years. As the photograph on page 87 shows, the practice of two aircraft flying towards each other on a collision course only to miss by feet was there in the Hendon display as it is with the Red Arrows today.

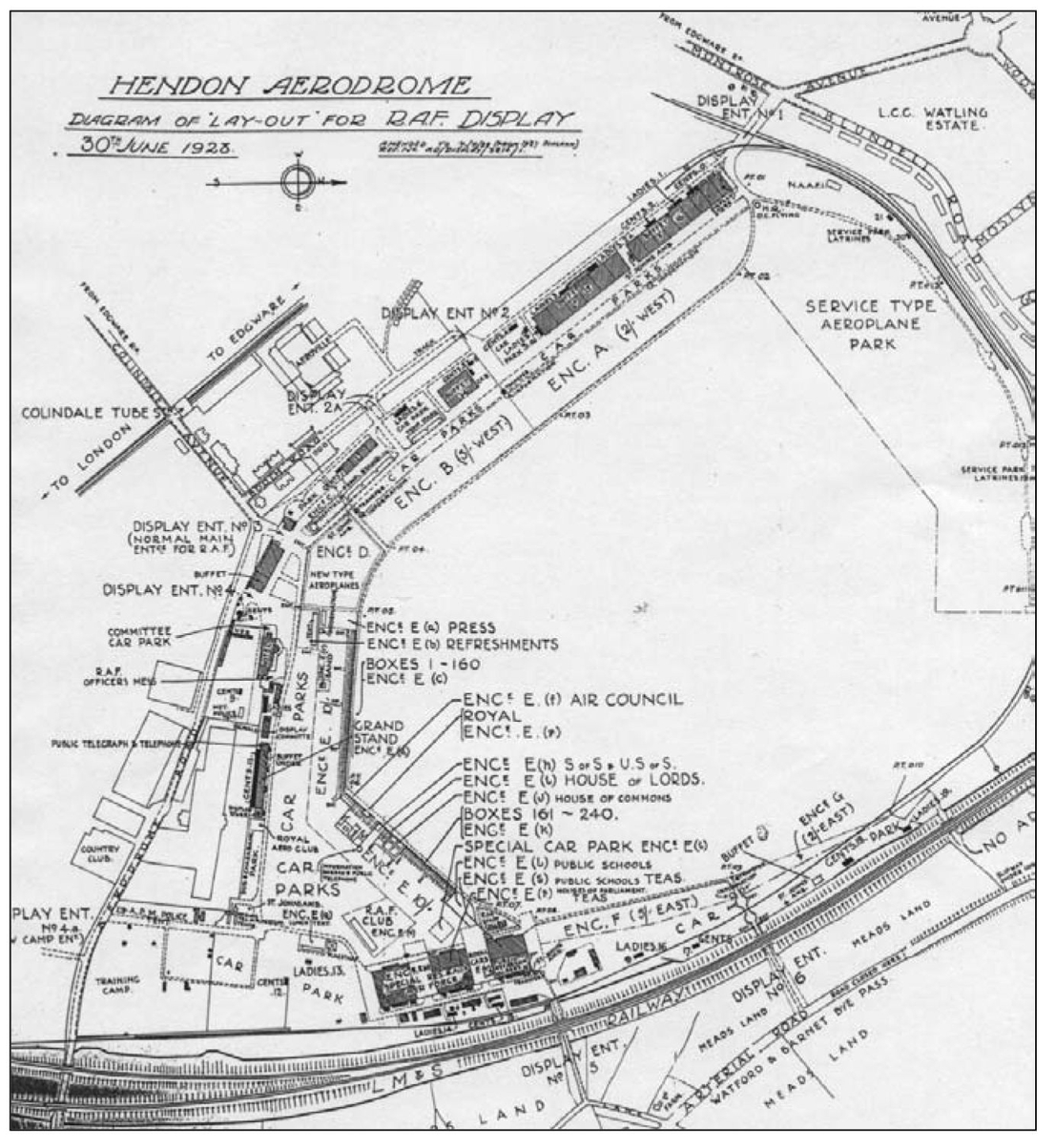

PLAN OF HENDON RAF DISPLAY, 1928

The 1928 Display

Notice the space reserved for royal visitors, Members of Parliament and the public schools in the plan below. The latter would provide the recruits to long-term commissioned service in the RAF via, in some cases, the university air squadrons. One must not forget the importance attached to this annual event as a public relations exercise. Members of Parliament needed impressing that the legislature was voting sums on a service that would be well spent. A public aware of the efficiency of the peacetime air force would support it and recruits would be forthcoming. By 1928, however, the threat of extinction posed by her sister services having receded, Trenchard could concentrate on his quest for quality. The RAF Display was his way of proving that quality.

The 1929 Display

Owing to the imminence of the Olympia Air Show, there was no parade of prototypes at Hendon, for this would have dented the impact of the former. But the 1929 Display did show off the ‘new look’ of the RAF, featuring the Siskin and Bulldog fighters and the Sidestrand bomber. One of the pilots who flew inverted in the Genet Moths was Flying Officer Dermot Boyle, later to become Chief of the Air Staff. The classic beauty of the Fairey Fox made it probably the most pleasing-looking aircraft of its time, and it was held that the banshee-like scream would have put the fear of God into many a hill tribesman in the Middle East or on the North-West Frontier. In fact the Fox was never used in air-control operations. It was the Wapiti that would replace the old DH9As and Bristol Fighters in those theatres.

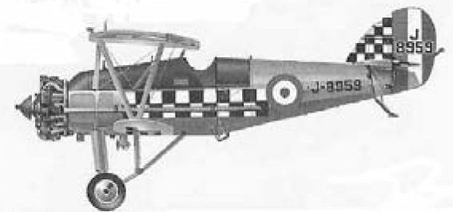

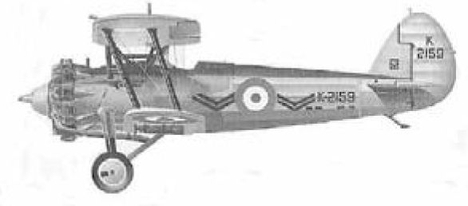

Siskin.

Bulldog.

Sidestrand.

The Aircraft and Armament Experimental Establishment, Martlesham

By 1926 the work of the A & AEE was respected not only in the RAF but in the aircraft industry and civil aviation. Although the work involved a considerable degree of risk, the test pilots knew that they were at the cutting edge of technology. The firm’s test pilots who brought the aircraft to Martlesham also shared the dangers of test flying, but it was left to the RAF pilots to test an aircraft to the limit to be sure that it would survive in combat. Harald Penrose, who became the chief test pilot of Westland Aircraft, described how he came to deliver the prototype Widgeon to Martlesham in February 1928. Remember these were the days when there were none of the formalities of flying today, such as flight planning and radio contact. He left Yeovil to fly eastwards, keeping a look-out for aircraft using airfields in his path, such as Old Sarum and Andover. He skirted London and droned eastwards across East Anglia to Ipswich before picking up the pine-fringed airfield that was his destination. There were no red or green Very lights. If the field and approach was clear, he said, one landed. Once there, he saw a wealth of new types in the hangars, such as the Gloster Goldfinch, Boulton Paul Partridge and the Rolls-Royce-powered Vickers 141, which caused him to reflect how far aviation had progressed in the few years since the epic flight of the Wright brothers. Test-pilot reports were readily accepted by manufacturers, who would often incorporate modifications into the basic design. At the annual Display the latest aircraft were on show and were flown by Martlesham pilots, those being the only ones with enough experience to fly new types. Accordingly the aircraft companies tried to ensure that they would have a prototype on trial at the time of the Display.

Gloster Goldfinch.

Boulton Paul Partridge.

Vickers 141.

Martlesham Airfield The airfield at Martlesham, in common with other airfields of the day, was unsurfaced and consisted of a large field of turf and close-cropped heather. This meant that aircraft could take off in pretty well any direction, according to the wind, but the prevailing one was south-westerly, and so the majority of take-offs were in the direction of the Dobb’s Lane corner of the airfield and the approaches were made over Martlesham village. Left-hand circuits of the airfield were usual, and since all landings were visual, the aircraft in circuit remained, for the most part, within the airfield perimeter. Until the introduction of tail-wheels, taxiing aircraft meant picking up quantities of turf and heather in the metal tail-skid.

Death of Flying Officer G.V. Wheatley To emphasize the danger of test flying, Flying Officer G.V. Wheatley was carrying out a terminal velocity dive in a Gloster Gamecock, from which he did not survive. The station experienced a lively social life and was a close-knit community. The loss of a test pilot, therefore, had a profound effect on those who knew him. A special memorial service was held in the men’s dining hall, attended by officers from Martlesham’s sister establishment, the Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment, and Shotley Royal Naval Training Establishment – in all some 450 officers and men. No. 22 Squadron personnel headed the cortège, and all three service padres officiated. Flying Officer Wheatley was buried amid a mass of floral tributes, his coffin draped with the Union Flag, and a firing squad fired the three volleys.

That’s test flying for you!! But at least this pilot crawled out uninjured.

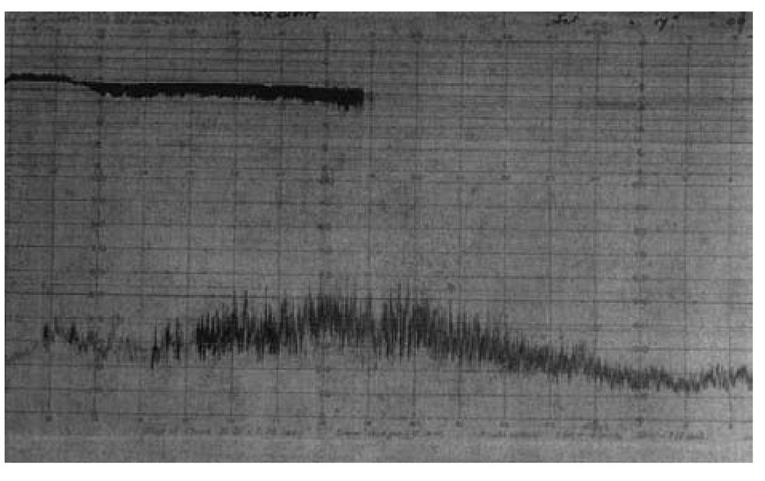

Other Hazards There were other flying hazards in the 1920s that are unheard of today. Nowadays fuel can be dumped if an aircraft gets into difficulty, this being particularly important just after take-off when the tanks are full. On 18 June 1927 Flight Lieutenant C.R. Carr and Flight Lieutenant P.H. Hackworth were flying a Hawker Horsley II, Serial No. J.8608, on a long-distance flight. They had on board 1,000 gallons of fuel when a sudden oil leak meant a forced landing. It was a considerable feat of airmanship to land without mishap. Their flight was from Cranwell to the Persian Gulf when the oil leak happened. Cranwell was the station from which long-distance flights took off, since it had a sufficiently large grassed area for a take-off run with a heavily loaded aircraft.