Chapter 5

Aircraft, Weapons and Defence Systems – Procurement and Development

The aircraft industry – Survival, growth, consolidations – O

construction – Open and closed cockpits – Test flying at Martle

of prototypes – Aircraft weapons – Bombi

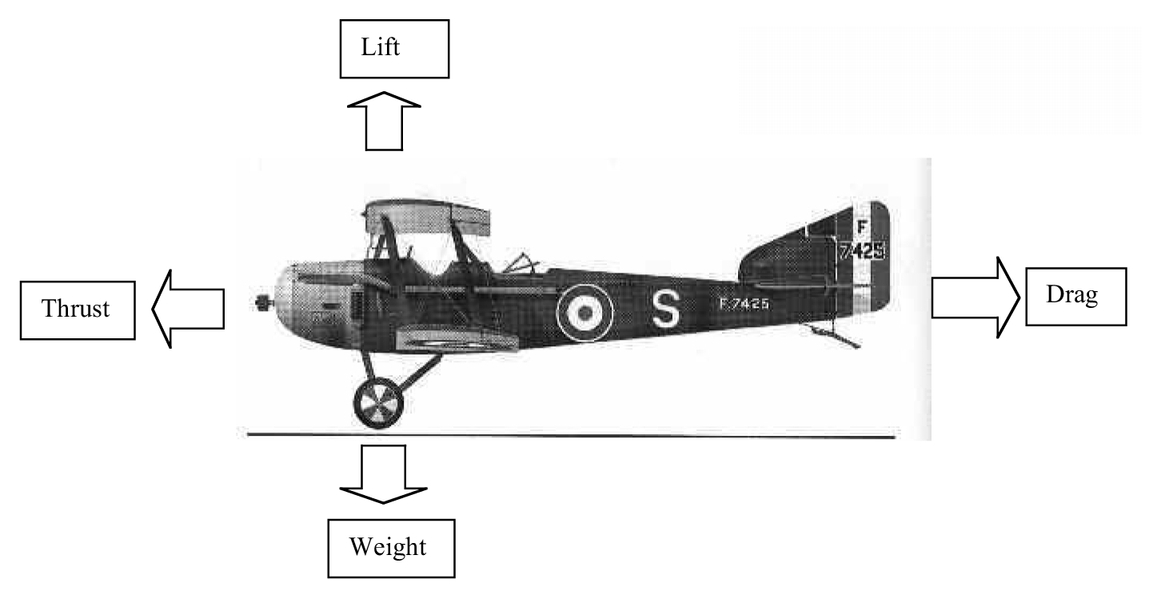

This chapter traces the development of the aircraft industry in Britain year by year over the period 1920 – 29. There are three outstanding themes that recur in the narratives that follow that may seem strange in an era of fast jet travel and supersonic all-metal aircraft. Firstly, there was the debate over whether aircraft should be made largely of wood, covered in fabric. The quality of wood as a raw material, its ease of working and relative cheapness made it attractive to people like old Dick Fairey of Fairey Aviation or to firms struggling to make a profit. Yet there were other firms, like Shorts of Rochester, that were determined to press ahead with all-metal construction. Secondly, there was the debate over biplane or monoplane. The attraction of the biplane was that, having two pairs of wings, the weight of the aircraft was spread over a larger wing area. This meant that wing loading was lighter, hence stresses were not as great. When the early monoplane designs like the Westland Dreadnought came to grief it is easy to see why biplanes remained in common use both commercially and in military service well into the 1930s. Thirdly there was the closed cockpit versus open cockpit debate. Again it seems unthinkable in the days of fast jet travel that any pilot would want to be exposed to the elements, but in the 1920s that was very much the case, and there was great resistance to the idea of closed cockpits. This may be partly explained by the desire to exit an aircraft quickly in an emergency, since, without parachutes in the early days, aircraft in trouble would be brought down for an attempted landing.

Weapons development does not feature greatly in Volume I since most advances were made in the 1930s and therefore mostly relate to Volume II. Aero engine development is very important and features in both volumes, and in this context the debate over air-cooled versus water-cooled, radial versus in-line, engines is of interest. Finally when it comes to defence systems some scientists are alleged to have worked on a ‘death ray’, but the only system of note and the one that was vital to the air defence of Great Britain in 1940 was radar.

1920

Aircraft Disposal

The British aircraft industry that provided aircraft for the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and the Royal Naval Air wners and designers – Biplane v. monoplane – Wood v. metal esham, Felixstowe and RAE Farnborough – Some notable flights ing techniques – Aero engine development

Service (RNAS) in the Great War, which began in August 1914, comprised such companies as Handley Page, Airco, Fairey, Sopwith, Avro, Bristol, Nieuport, Armstrong Whitworth, Wight, Vickers, Short and the Royal Aircraft Factory. These companies grew to meet the needs of the RFC and RNAS, which later merged to become the Royal Air Force in April 1918, and even as the war ended in the following November new types were entering squadron service, aircraft such as the V/1500 four-engined strategic bomber. But with peace came a rapid rundown, leaving a huge surplus of some 10,000 warplanes (see page 165). These aircraft were held, on the government’s behalf, by the Aircraft Disposals Board, but a syndicate registered as the Aircraft Disposal Company Ltd purchased these aircraft from the Ministry of Munitions. The aircraft company Handley Page Ltd acted as technical adviser and sole selling agent. Handley Page had already sent missions to overseas countries with the aim of exporting these war-surplus aircraft. It was the policy that all machines would be refurbished prior to sale. This involved stripping the aircraft down and replacing nuts and bolts, worn moving parts and engines if required. The result was an as-good-as-new product. Refurbished aircraft could also equip RAF units requiring replacement aircraft, aircraft like the Bristol fighter and the DH9A, nicknamed the Ninak, which saw service into the early 1930s.

Such was the more rudimentary design of aircraft in 1919 that service aircraft could quite easily be adapted for civilian use and vice-versa. Indeed, with the advent of peace the size of the civil air fleet of a potential enemy was deemed to constitute a threat if its civil aircraft could be converted to the bombing role. Given, then, that the war-surplus aircraft could be exported, used for domestic civilian purposes or used to re-equip RAF squadrons, the Aircraft Disposal Company Ltd posed a threat to the survival of the nascent aircraft industry. Indeed, if Britain was to remain in the forefront of aircraft design and development in the postwar years, if only to produce military aircraft superior to those of any potential aggressor, it was vital for these companies to retain their design staff and at the very least a nucleus of production staff.

WAR-SURPLUS AIRCRAFT PURCHASED BY THE AIRCRAFT DISPOSAL COMPANY LTD Some 10,000 aircraft which included:

DH6

DH9

DH9A

DH 10

SOPWITH CAMEL

SOPWITH PUP

R A/C FACTORY FE2B

R A/C FACTORY BE2E

R A/C FACTORY SE5A

BRISTOL FIGHTER

VICKERS VIMY

AVRO 504K

SOPWITH SNIPE

MARTINSYDE ELEPHANT

SOPWITH DOLPHIN

Survival

This, then, is a story, firstly, of survival in the immediate postwar years. The Bristol Aircraft shops were almost empty of aircraft, for all contracts had been cancelled, so work went over to tram-car bodywork and the construction of saloon bodies for Armstrong Siddeley cars. Indeed every aircraft company was seizing on any kind of work to keep going. Avro was into cars, Short into bus bodies and marine craft, and Sopwith and Martinsyde into motor cycles. But things were going from bad to worse. At the flying school in Cambridge aircraft were being sold at auction at rock bottom prices. DH6 trainers, for example, were going for just £2 5s (£2.25). Manufacturers who had aircraft ready for the Schneider Trophy international seaplane races found that they could not afford to send them. Nieuport and General Aircraft Company Ltd had to close their works when the slump hit the aircraft and motor industries, and on 11 September the Sopwith Aviation and Engineering Co. Ltd went into voluntary liquidation. When firms went into the hands of the Receiver the Treasury seized the works to realize excess profits’ duties payable as a result of wartime contracts. Banks and other creditors received nothing. Also hit was the Air Ministry Competition at the Aircraft and Armament Experimental Establishment, Martlesham Heath, in Suffolk. Airco, maker of the DH6 and DH9, had to scratch because of the company’s liquidation. Neither the Beardmore nor Saunders aircraft were ready for the competition, and so only Handley Page or Westland could be winners.

Both military and civil aviation came under the control of the Air Ministry, and a portion of the Air Estimates voted annually by Parliament was earmarked for civil flying. As has been pointed out, the aircraft industry relied upon civil aircraft orders as well as export and RAF orders. Since the latter needed a strong and confident aircraft industry, the state of civil aviation is relevant in this context. The link between civil and military aviation is further emphasized by a view expressed by the Controller-General of Civil Aviation at an air conference in October 1920, when he said, ‘The nation which is strongest in air traffic will be the strongest in aerial warfare of the future.’ Fear was expressed that the aircraft industry would crumble to pieces. Of the £2 million in the Air Estimates for research and supply, only £500,000 went to civil aviation, the rest to the RAF. It was the sheer financial risk of building aeroplanes on speculation for the RAF when orders might not be forthcoming that troubled the pioneers of aviation. Herbert Smith, Sopwith’s designer, said that, in his opinion, ‘The day of the large aeroplane has not yet come and much remains to be investigated and determined concerning multiple-engined machines. The Sopwith Company are at present pinning their faith on single-engined aeroplanes of moderately high speed. They are constantly receiving enquiries but orders are not exactly plentiful as they desire and the Air Ministry does not provide the help and encouragement expected of them.’

Avro 504Ks overhauled at the Aircraft Disposal Company outside the company works at Croydon for sale to overseas military and civil buyers.

ENGINES AND SPARES PURCHASED BY THE AIRCRAFT DISPOSAL COMPANY LTD

The 35,000 engines included: Other engines were produced by:

| Rolls-Royce Eagles | Fiat |

| Rolls-Royce Falcons | Anzani |

| Napier Lions | Renault |

| Siddeley Pumas | ABC |

| Wolsley Vipers | Le Rhône |

| Wolsley Adders | Clerget |

| Hispano-Suizas | Monosoupape |

Avro 504K fuselages stacked inside the Croydon works, stripped and rebuilt to emerge as good as new.

Spares held:

Between 500 and 1,000 tons of ball-bearings, 350,000 spark plugs, 100,000 magnetos, and a vast store of nuts and bolts.

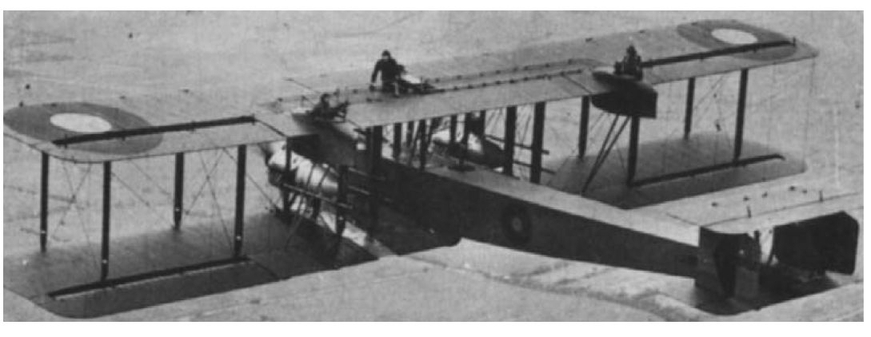

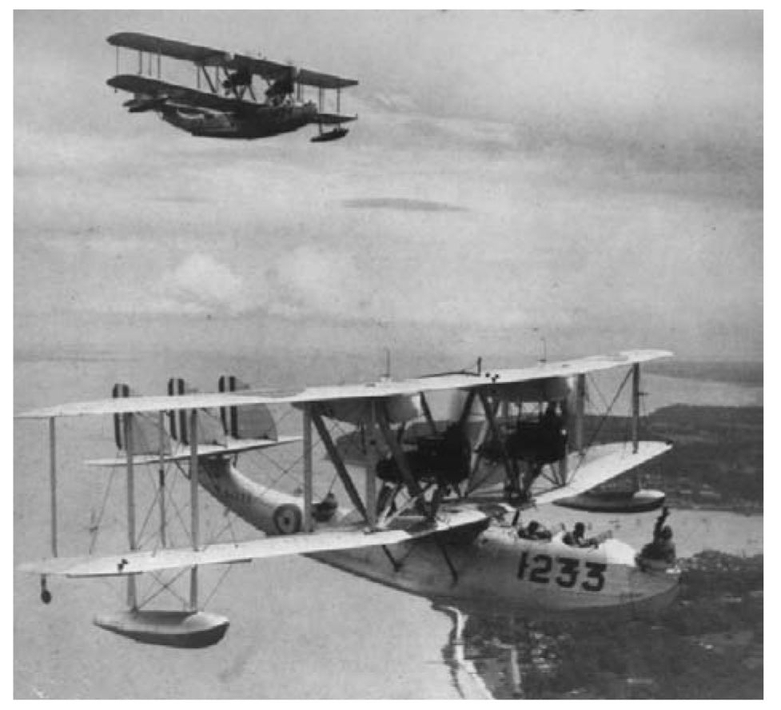

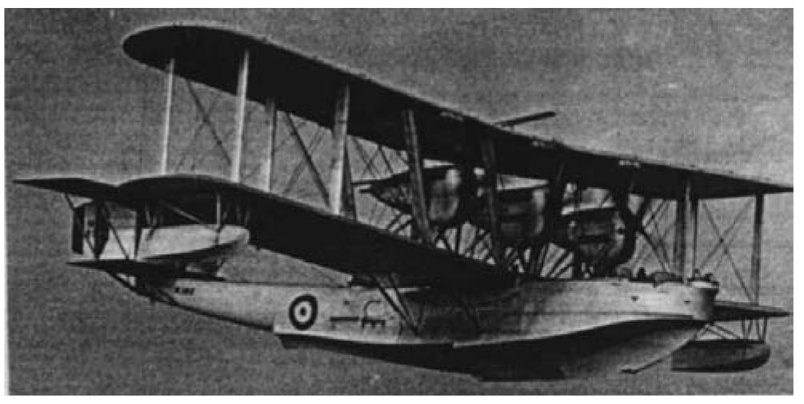

Additionally the syndicate held some large and small flying-boats, such as the Blackburn Baby, and a few Handley Page 0/400 two-engined bombers below:

VALUE OF ENTIRE STOCK OF AIRCRAFT, ENGINES, EQUIPMENT AND SPARES: £5,700,000

THE SYNDICATE PAID:

£1,000,000 on condition that half the profits of the sales would be repaid to the government.

State of civil airlines The regular services between international and domestic airports that we take for granted today were unknown. There were few domestic airports, although local authorities were asked to purchase land for airfields to create a network for civil airlines. There were no air corridors where aircraft travelled at an agreed height with vertical and horizontal separation between aircraft in flight, and no blind-flying aids. Transatlantic and other long-distance commercial flights lay in the future. Air taxi work was popular, as was joy-riding, and this was the foundation in Australia for the Queensland and Northern Territories Aerial Services (now the famous QANTAS), which began these services in Western Queensland on 16 November 1920, albeit with a subsidy from the Australian government. But within Britain too joy-riding was an immensely popular pastime, and there were plenty of old service aircraft and ex-RAF pilots to do just that. Because distances between destinations in western Europe were relatively short, and with nearly all the intended airline flights taking place over populated areas where help was on hand, regular passenger and freight services were a distinct possibility. A typical return fare to Paris in 1920 was 18 guineas (£18.90) and the single fare 10 guineas (£10.50). Freight charges were 2s (10p) per pound, and less for larger consignments. Civil air transport companies had to persuade London businesses to send their freight by air rather than rail and boat. But as 1920 drew to a close, winter weather caused flight cancellations and thus reduced incomes. Businessmen could not therefore rely upon aircraft to meet deadlines. Scores of forced landings had to be made because of bad weather and engine failure. Putting down in a field today would be unheard of, but in the inter-war years it was quite common for civil aircraft for the reasons given and RAF aircraft on training flights to put down in a field, if only to allow the instructor to pick mushrooms for dinner!

Not unsurprisingly the London – Paris air services were not prospering. The Daily Mail’s Paris correspondent reported on 6 December that Air Transport & Travel Ltd was bankrupt and the Instone Airline had laid up its aircraft for the winter. Handley Page Transport was not running a regular service, flying only when there were passengers or freight to warrant it. To make matters worse, Robert Bager, HP’s chief pilot, was killed when his aircraft hit a tree and burst into flames after taking off in mist from Cricklewood.

Aircraft company intentions At A.V. Roe Ltd the convalescent Roy Chadwick was intent upon a single-engined heavy bomber. This was to be the Aldershot. Vickers was invited to tender for a long-distance twin-engined bomber with flat top wing and dihedral on the lower wing.

The cost seemed remarkably low, and an initial order was placed for two airframes, each at £13,250. The Vickers Viking, which had a retractable undercarriage, was test-flown at Brooklands by Captains Cockerell and Broome. Armstrong Siddeley offered a similar product. At Short Brothers, Oswald Short was intent upon his all-metal Swallow, later to be called the Silver Streak, even though the Air Ministry metallurgists were backing high-tensile, thin-walled, steel girder frames with conventional fabric covering for fuselage and flying surfaces. There was a setback for the development of super-large aircraft when Felixstowe lost its Fury triplane flying-boat, which stalled and crashed on take-off, drowning its pilot, Squadron Leader ‘Rolly’ Moon. Armstrong Whitworth felt that there was still a place for a fighter aircraft in spite of the economies forced on the Air Ministry and the surplus of machines held by the Aircraft Disposal Company, and was pushing the Siskin, an aircraft not unlike the SE5.

Investigations into aircraft handling At RAE Farnborough the chief test pilot, only 26 years old, was Squadron Leader R. M. Hill MC, AFC. He was making the first-ever detailed investigation into the flying characteristics of aircraft. For example, it needed to be explained why a very stable aircraft in straight and level flight, with a trimming tail to compensate for variations in the disposition of weight in an aircraft, e.g. pilot, bomb load, stores or passengers, could almost fly by itself at most speeds, but was less manoeuvrable, stiff and unresponsive in a dive, and was generally more unwieldy. The Sopwith Camel and SE5 fell into this category. Squadron Leader Hill described the DH9A as excellent because of its general handiness and straightforward control. The HP 0/400, on the other hand, would only feel nose heavy in a dive if badly out of trim. The Vickers Vimy felt very nose heavy as it always diverged from its stable trimming speed, and at 120 mph the force was so considerable that the pilot had difficulty in pulling up the nose. The DH10 was satisfactory in flight but was tricky during take-off. When it came to lateral and directional stability the SE5A was excellent, but the Bristol Fighter was so poor that it was difficult to keep an accurate compass course when in cloud. Hill warned that more powerful aircraft of future design might have characteristics that would render even simple manoeuvres such as landing fraught with difficulty, or a medium-sized, under-powered, lightly loaded aircraft could be difficult to get off the ground. Such then were the problems to which Squadron Leader Hill had to put his mind.

Aircraft engines Things were a little better for British aircraft engines that were displayed at Olympia in 1920. They showed that great strides had been made in the five years since pre-war days. The Jupiter engine display secured for Bristol a contract from the Air Ministry for ten experimental engines. The company’s biggest rival was Siddeley, with its 300 hp 14-cylinder Jaguar. Although Rolls-Royce was the most firmly established in the aero engine field, the company was at this time more interested in car production, and the aero engine department was confined to overhauls of existing engines. Napier was developing a double V 1,000 hp engine, that is to say an engine that was X shaped in end view. The Air Ministry had ordered this engine in 1919 at a price of £10,000 per unit. Other firms at Olympia were Beardmore, Gwynne and Sunbeam. Finally the Aircraft Disposal Company had a stand, and could undercut the engine makers for spares, instruments and magnetos.

1921

Air Ministry orders Early 1921 saw the RAF, ever mindful of the need to help the ailing aircraft industry, awarding contracts to Avro for its Aldershot bomber, to Vickers for its Vimy bomber, to Bristol for its shaft-driven powered biplane, to Boulton Paul for a similar aircraft and to Fairey and Parnall for their two-seat amphibians. The Westland Company at Yeovil was completing an Air Ministry order for extensive modifications to the DH9A, converting it to a three-seater for naval use with a Napier Lion instead of the usual Liberty engine. Supermarine had received an order for the development of a single-engined commercial amphibian flying-boat named the Seal. Some companies used to develop their own aircraft to prototype stage called private-venture projects. So it was that the Air Ministry purchased the private-venture Swift from Blackburn, which then bore the Serial No. N139 instead of the civilian designation G-EAVN, but tests at Martlesham showed the rudder to be too small.

Engine orders Development contracts had also gone out for engines, notably to Bristol for its Jupiter and to Armstrong Siddeley for its radial engines, for the Napier 1000 hp Cub, and for the 600 hp Rolls-Royce Condor to go in the scaled-up version of the DH9A, the DH14.

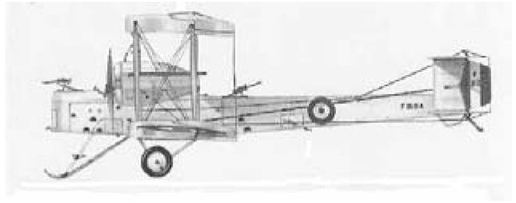

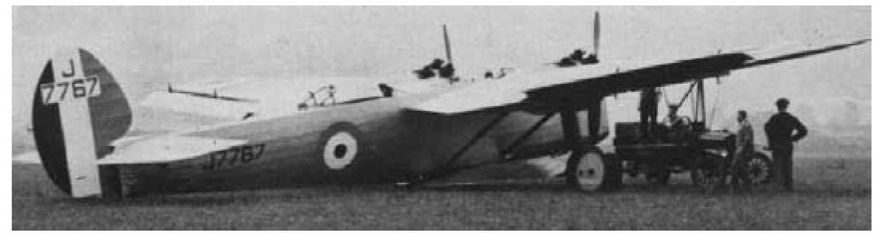

The DH14.

The DH14 The DH14 had been ordered in 1918 as a replacement for the DH9A, but in spite of its good performance, all the urgency had gone once hostilities ended, and although the prototype J1939 was delivered to Martlesham for testing and evaluation, a contract for production was not awarded and it did not, therefore, enter RAF service. Although Britain had only two aircraft on display at the Paris Air Show, the Bristol Jupiter made up for it. The Jupiter was the first to pass the 100-hour running test, and attained 450 hp. This was followed by a British government order for forty-two Jupiter engines with 100 per cent backing of spare parts.

The Aircraft Companies in 1921 de Havilland To assist matters financially, contracts were issued for the repair of aircraft and engines. Indeed, for the next ten years the RAF, operationally in its air-policing role, was to stagger on with repaired and refurbished Bristol Fighters and DH9As. In a period of austerity it was all that could be expected. DH9s and DH9As were being rebuilt at de Havilland’s Stag Lane works. The aircraft would be stripped down and all small parts on the fuselage and aircraft could be passed off as new. The DH29 monoplane was causing de Havilland concern over the machine’s behaviour, and so a biplane replacement was being designed. The DH32 was set to replace the DH29, and was to be powered by the Rolls-Royce Eagle engine at a price of £1,000.

The DH29s were needed for the Daimler Airways new cross-channel service in the spring of 1922, and so de Havilland was offering the DH32 instead.

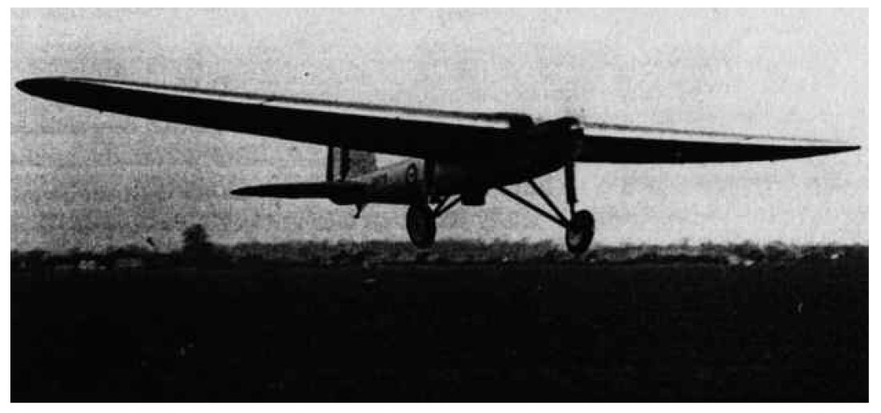

DH29 Airliner.

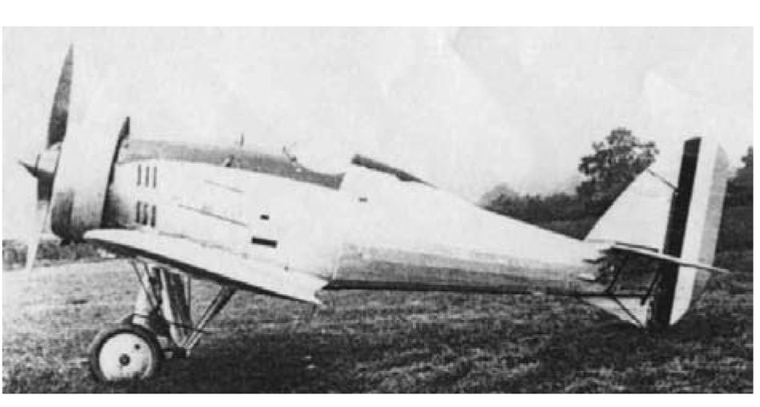

The Bristol Aircraft Company Bristol, on the other hand, had had an order for three of its Bullfinch fighter. Its designer, Captain Frank Barnwell, was disheartened that this and his other military projects had been turned down. His single-engined monoplane could be converted to a two-seat reconnaissance biplane by adding a small lower wing, but to no avail. So he resigned from Bristol and accepted a commission in the Royal Australian Air Force, to be posted to its Aircraft Experimental Department at Randwick. The experience of de Havilland and Bristol is of considerable interest in the debate that kept resurfacing during the inter-war years, namely biplane versus monoplane and enclosed cockpits versus open cockpits. As with the DH29, so also with the Bristol prototype, the concern was about the stability of monoplanes. Aircraft with two wings meant that the aircraft’s weight was shared between two wings rather than a single one with the resultant low wing loading. As for enclosed cockpits, they were simply not favoured by aircrews.

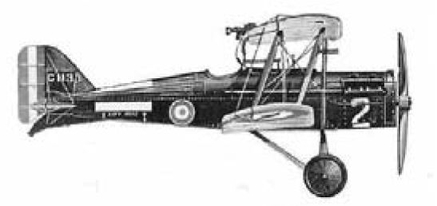

Bristol Bullfinch.

Short Brothers One of the most famous and long-standing test pilots of the period was John Lankester Parker, whose name will crop up several times in this chapter. In early 1921 he was test-flying the Short Silver Streak. It should be remembered that aircraft, having been test-flown by the manufacturer’s test pilot, were handed over to the RAF team of test pilots at Martlesham in Suffolk, for evaluation as either a military or a civil aircraft. Civil aviation came under the Air Ministry at this time, and civil prototypes would therefore be tested. Obviously military aircraft would be placed under greater stress in dives and spins, rolls or loops. Remembering the financial plight of most aircraft companies at this time, company managers were eager to hand over prototypes to Martlesham, for which they received payment from the Air Ministry. There were times when Lankester Parker was not entirely happy with a prototype, but had, reluctantly, to deliver it to Martlesham. The Silver Streak had been built with an aluminium skin, but this rippled in flight and was replaced with duralumin. The RAF test team, Squadron Leader Roderic Hill, Flight Lieutenants Noakes and Scholefield, flew the aircraft up to 10,000 ft. With a top speed of 125 mph, ease of control and excellent manoeuvrability, it was agreed that the performance was astonishingly good, yet no further test flights were authorized. Priority by the Air Ministry at this time was given to steel-girder fuselage construction rather than streamlined monocoque. Unlike civil aircraft, military types would be placed under more severe stress to simulate combat conditions. The Silver Streak was not accepted.

Paris Air Show The Paris Air Show opened on Saturday 14 November 1921, but such was the state of the British aircraft industry with its lack of confidence in international sales that only two aircraft were on display. One was a torpedo-bomber with a 370 hp Lorraine engine, and the other was a Vickers Vimy Commercial powered by two Napier Lions.

Life for civilian pilots at Croydon in 1921 An insight into the development of flying in those early pioneering days can be gained by looking at the life of pilots, most of whom were in their mid-twenties, who worked out of Croydon in 1921. These young men often arranged a weekend race meeting, using joy-riding aircraft such as SE5As. The pay was not great and they might supplement their incomes by production-testing aircraft of the Aircraft Disposal Company for a fee of £1. If an aircraft was delivered to the continent, a pilot’s return fare would be deducted from his fee. Whereas most airline pilots wore a motley variety of civilian attire, Instone Airline introduced uniforms based on the naval reefer jacket. Refuelling was improved when a battery of pumps appeared in the Customs enclosure provided by the rival companies. Previously aircraft had had to be refuelled by hand-operated bowser and petrol cans, and as an aid to navigation for pilots using Croydon and Lympne airports aerial lighthouses were erected to help in conditions of poor light. These lights could be seen for some thirty miles.

1922

Wood v. Metal Construction

Wooden construction To add to the continuing debate on the merits of biplanes versus monoplanes and open versus closed cockpits was that of wood versus metal aircraft construction. Geoffrey de Havilland, for example, did not believe that all-metal construction was practicable at that time. He believed that the life of a wooden machine was longer than generally believed and was cheaper to construct. But manufacturing firms found it difficult to assess how well their products performed in respect of durability since aircraft were taken away by Martlesham for testing and evaluation by the RAF team of test pilots. De Havilland pleaded for government support to enable manufacturing firms to carry out more full-scale flying tests. The case of the DH34 was cited. It underwent airworthiness tests in one day at Martlesham before being delivered to Daimler Airways at Croydon on 31 March 1922. Only very obvious faults would be detected and no dive was attempted. Tom Sopwith, with his wartime experience, added his voice. He emphasized how quickly new designs constructed with wood could be built, tested and abandoned, if need be, like the semi-cantilever parasol monoplane built to Air Ministry Specification 7/22 and named the Duiker. This was abandoned after test.

All-metal construction Others argued that using metal was rather more a science than an art. It was held that all-metal machines could be built 10 per cent lighter than wooden structures of the same dimensions. During 1922 more work on all-metal aircraft was evident and tubular-steel structured-girder fuselages were favoured. Westland was using metal construction but restricted it to wing spars.

Aircraft Companies

Avro and Westland Bert Hinckler became the chief test pilot for A.V. Roe Ltd in 1922, and flew its first postwar service prototype, the fleet-spotter Type 5SS Bison. The pilot sat up high in front of the top centre section of the wing, with a steeply sloping cowling for maximum deck-landing view. But the first flight revealed similar problems to those experienced with the de Havilland monoplane through interference between wing and fuselage exacerbated by the leading edge of the cockpit opening. This caused directional instability, and the elevators and full-span ailerons required too much strength to operate. The Walrus, produced by Westland, had suffered many crashes and was thus regarded as a stop-gap aircraft. Avro and Blackburn were aiming to replace it.

Westland Walrus.

Avro Bison.

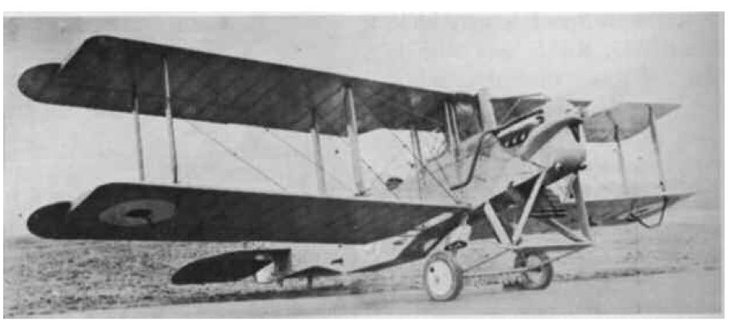

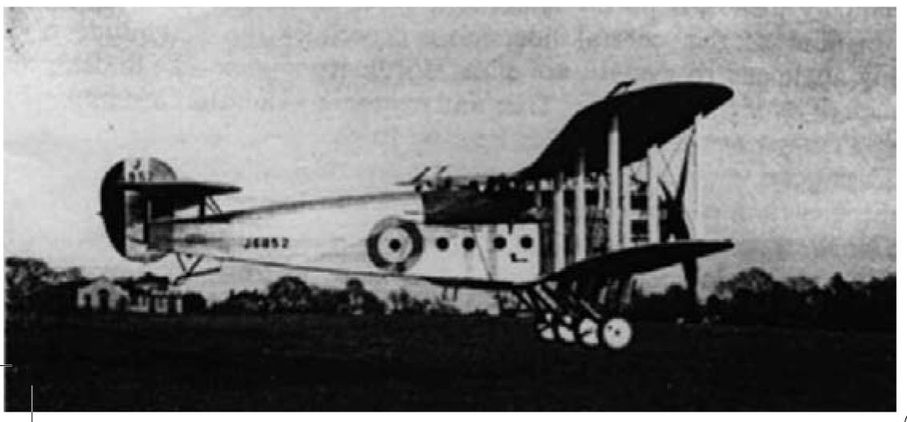

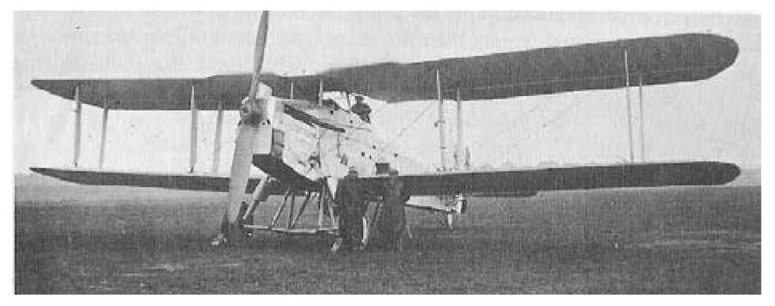

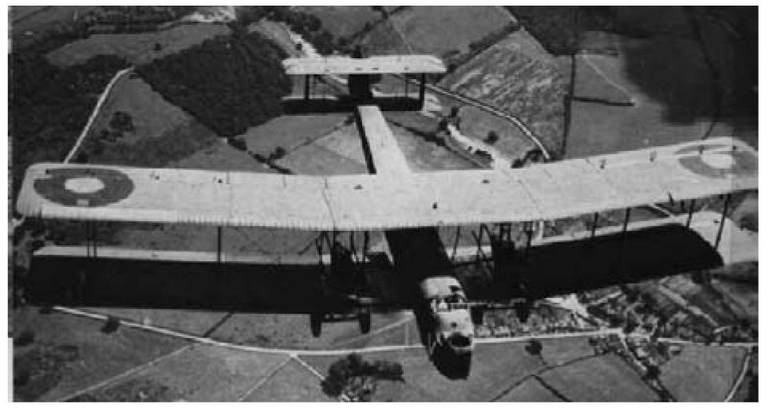

Vickers Victoria, Virginia and Vixen Up to now the RAF had the Vimy as a bomber and the Vickers Vernon as an air ambulance, both of which provided satisfactory in service, and so the Air Ministry had no immediate need to replace them. Work on their replacements had therefore been slow. The Victoria transport capable of carrying twenty-three troops and a crew of two had been trialled at Vickers and was at Martlesham for testing. On 24 November 1922 the Vickers test pilot, Captain Cockerell, had made the maiden flight of the prototype of the Virginia bomber, Serial No. J6856. The Victoria was a very similar machine to the Virginia except for its bulky fuselage. Since Cockerell considered the Virginia’s rudders were too small, the prototype with larger rudders went to Martlesham on 11 December for full load trials. Although there was trouble with vibration in the starboard engine, it was a popular aircraft with the test pilots. The private-venture Vixen two-seat biplane was almost ready, but with the ‘Geddes Axe’ falling on the RAF it was unlikely that there could be more than token orders for what Vickers hoped would be a replacement for the Bristol Fighter and DH9A. The latter were to remain in service abroad into the 1930s.

Vickers Victoria.

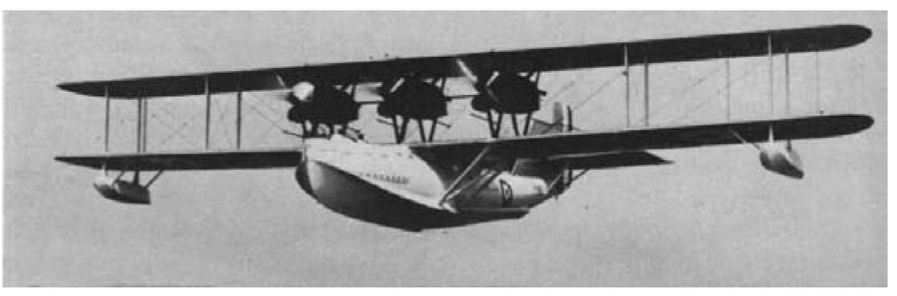

Vickers Virginia prototype (J6856). Later modified to a MkVIII with ‘fighting tops’, seen above.

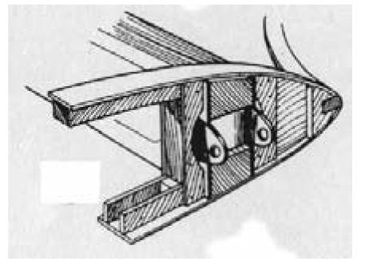

Handley Page W8b and HP21 The Handley Page W8b civil airliner is an example of where a civil prototype could, with modification, become a military type. At Martlesham tests showed that the aircraft could be flown straight on one engine but would lose height with an all-up weight (AUW) of 12,500 lb. A reduction of 1,000 lb, the equivalent of a third of the fare-paying passengers or all the fuel load, meant that the aircraft could remain aloft on one engine. It had a low landing speed of 40 – 42 mph but a poor climb with a full load. The design was being modified to become a heavy bomber, the Hyderabad. Richards, the Handley Page designer, was also working on wing slots to give high lift with a smaller wing. The US Navy was interested for future fighters, space being at a premium in an aircraft-carrier. What was ingenious was the mechanism that controlled the leading-edge slot and trailing-edge flap, which was the length of the wing. The mechanism incorporated differential for lateral control, i.e.lateral control could be maintained in whichever position the flap was lowered. Flaps and slots together make possible low landing speeds without the risk of stalling, in this case 44 mph with slots and flaps at maximum lift. Richards had put the new slots and flaps into the HP21, of which three had been ordered by the US Navy, with an option on a further twenty-seven, but the Air Ministry had doubts about Richards’s design, regarding it as too complicated.

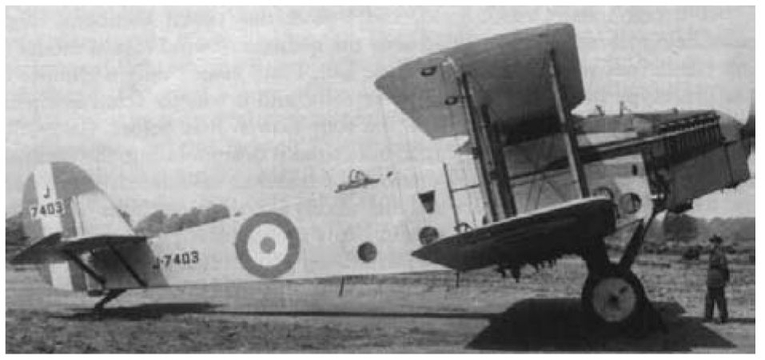

Handley Page Hyderabad.

Aircraft safety – parachutes and fuel tanks The staff officers at the Air Ministry were more concerned, in 1922, with fire risk than the safety afforded by parachutes, and a competition, which attracted twenty-six entries, was for a fuel tank that could withstand machine-gun and shell fire and would not burst open or leak following a crash. The first prize went to the India Rubber Gutta-Percha & Telegraph Works Company Ltd. But there would be the problem of extra weight. The RAF, as has been noted, were not showing an interest in the Calthrop parachute, the ‘Guardian Angel’, which was designed to lift a man from an aircraft falling out of control. A small parachute deployed, to pull out a second then the third man-carrying chute. A demonstration using an Avro 504 K, piloted by Captain Muir at Croydon in early May, was successful, but the parachute was deemed too clumsy and heavy. This was inevitable since the design had to ensure that the parachute would stream whatever the attitude of the aircraft. This meant loose folding with a circular diaphragm spring inserted across the mouth of each parachute.

1923

State of the aircraft industry By 1923 the aircraft industry was reduced to such a state that only 2,500 men and women were employed in it, and of the few firms engaged in the manufacture of aircraft and engines some were on the verge of closing down. Following the announcement of an expansion plan to take the RAF up to fifty-two squadrons (seventeen fighter and thirty-five bomber) for home defence in an unspecified number of years, the Air Ministry was then faced, not only with having to buy back airfields against much local opposition, but with having to equip these squadrons either with obsolete types from the Aircraft Disposal Company or from an aircraft industry that was in the state described. In order that the aircraft manufacturing firms could hold on to their core design staff and builders, the Chief of the Air Staff, Air Marshal Trenchard, saw to it that, if nothing else, firms got contracts for prototypes. Developing aircraft to the prototype stage in 1923 was nothing like as protracted as it is today, when it takes several nations, not companies, to collaborate to build a fighter or bomber such as the Tornado or European Fighter aircraft. Indeed this was part of the case for constructing aircraft out of wood. A prototype could be quickly and cheaply constructed, and even if no production contracts followed, a company at least received payment for the prototype.

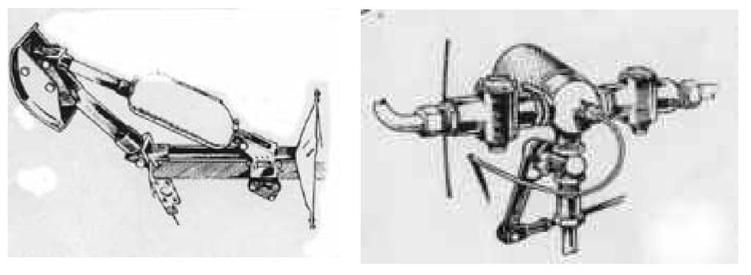

Wood v. metal construction This is a cue to return to the continuing debate. The question now was, should aircraft be constructed in duralumin or thin steel sheets? Duralumin, favoured by the French, was cheaper and thicker (weight for weight), and it had intrinsic stability – therefore a simple method of making spars that ran through the wings and tailplane was to draw duralumin tube to rectangular section, which was much cheaper than the riveted steel used by British firms. Professor Junkers was an advocate of duralumin, but Handley Page contested the statement that the material does not deteriorate. The duralumin floats of Junkers seaplanes leaked at the joints and had to be replaced by wooden ones. The Air Ministry forbade the use of duralumin for highly stressed aircraft parts, preferring instead high-tensile steel, arguing that most of an aircraft is highly stressed. Avro and Blackburn were cautiously introducing metal components, whereas Fairey and Parnall preferred wood as the immediate economic material. Typical aircraft components of mixed wood and metal included, from left to right below, the tail skid for an SE5, a combined oil and fuel cock with fuel equalizer box and wing root fillings.

Prototypes – Aldershot and Andover It is difficult to imagine a so-called heavy bomber today being driven by one engine, but this was the case with the Aldershot. It was a large machine and did look imposing with its large four-bladed propeller and double undercarriage. Roy Chadwick at Avro compromised with regard to the use of wood and metal in the Aldershot. The fuselage was metal-tube framed with wooden wings, fin and tail, and the aircraft was powered with a Napier Cub X 1,000 hp engine. The prototype, Serial No. J6852, was flown for the first time at Hamble in October 1921 with Bert Hinkler at the controls. Sir Geoffrey Salmond with Air Ministry officials were present to witness the maiden flight, and they saw Hinkler take off in just 200 yards. Press reporters were told afterwards that it was ‘nice on the controls and easy to manage’. In January it was delivered to RAE Farnborough, where its stability in flight made it a suitable candidate for night flying. It was hinted that a variant fitted with the Condor engine to be used in the passenger/transport and ambulance roles would attract a production order. The Aldershot was eventually to equip No. 99 Squadron at Bircham Newton, Norfolk. The variant was to be the Avro 561, later named the Andover. It was to replace the DH10s on the Cairo – Baghdad route.

Avro Aldershot.

Avro 561 Andover.

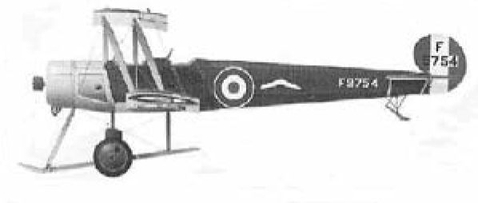

The Fairey Fawn The Fairey Fawn Mark I prototype was built to Air Ministry Specification 5/21 and had a short fuselage. The Fawn II, built with a longer fuselage, was more stable in flight, but the eventual production model built to Air Ministry Specification 20/23 was the Fawn III, powered by a 470 hp Lion II engine. Notice the ‘Hucks Starter’, which was in common use in starting an aircraft in the 1920s.

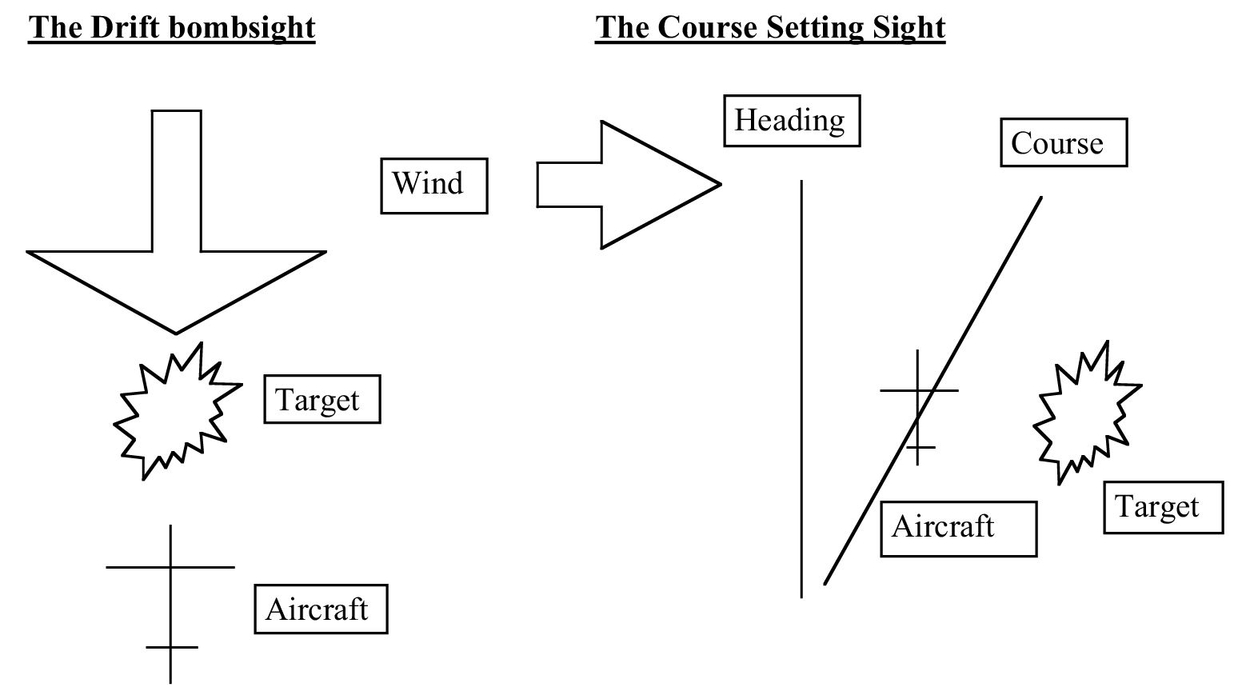

Weapon development Nothing so far has been said about aircraft weapons development. For the whole of the 1920s little was done in this field. The real advances were made during the rearmament of the mid- to late 1930s. The two guns used in nearly all RAF aircraft were the Vickers or Lewis gun. These could be mounted in one of several positions in the aircraft and were either fixed or trainable. Fixed meant that the aircraft and not the gun had to be pointed at the target, and sights were fitted in front of the pilot’s line of vision. If fixed guns were mounted on the fuselage to fire within the arc of the propellers, they had to be synchronized with the movement of the propeller blades, so as not to hit them when fired. Interrupter gears had been fitted to aircraft during the First World War. Before the interrupter gear was introduced, angular blocks of metal were fitted to the propeller blades so that if a bullet struck them it would, hopefully, glance off and not hit the aircraft or any member of its crew. A trainable gun was one which could be aimed by a gunner, who might be the pilot or another crew member, at a target and did not rely on the aircraft being pointed at the target. These trainable guns could either be fitted on the upper wing of a biplane to be fired by the pilot, or in a cockpit, mounted on a Scarff ring, and in multi-engined aircraft such as bombers in a gun position in the nose, amidships or in the tail. These were called the nose, tail, ventral or dorsal positions. Work carried out at the Aircraft and Armament Experimental Establishment included the improvement of gunsights; the introduction of a slimmer 0.303 in. round for RAF use, because standard Army ammunition did not perform well in the airflow, when bullets lost velocity in flight; investigations into the effects of cordite burning in machine-gun barrels; and the fouling of the rifling of gun barrels by a composition of carbon and metal from the cartridge rim. When it came to bombing, advances had been made since the days when bombs were simply dropped over the side of the fuselage. It was the bombsight and not the bomb-release gear that was vital to get right. Captain Henry Tizard, while at Martlesham, tested a high-altitude drift sight for use up to 17,500 ft, but this had limitations since it was only effective either directly up or down wind. What was needed was a sight that could place a bomb on a target regardless of wind direction. In 1924 the Course Setting Sight, which allowed for a wind vector, was introduced (see below). Apart from that there were some ad hoc arrangements made by resourceful unit commanders in the Middle East when carrying out air-control operations against dissident tribesmen.

Fairey Fawn of No. 100 Sqn.

The aircraft approaches the target either directly, up or down wind, and thus allowance has to be made only for a tail or head wind.

The 1924 Prototypes and Design Development Prototype contract for a day-bomber Westland, Bristol and Handley Page all secured a prototype contract for a single-engined day-bomber capable of carrying a 1,500 lb bomb, Air Ministry Specification 26/23. The Aldershot has already been described, and this did see service with No. 99 Squadron at Bircham Newton, but only fifteen had been ordered from Avro since it was considered too big and unwieldy.

The wind is blowing from the west, so the aircraft’s nose is pointed to the west (the heading) of the course actually desired, and when the bomb is released it, like the aircraft, will be taken downwind.

Westland Dreadnought The Dreadnought provides another example of the industry trying to move towards monoplane construction, and this prototype was expected to establish a new generation of fighter and transport aircraft. With the Westland’s test pilot Stuart Keep at the controls, the maiden flight was made at Yeovil on 9 May 1924. He made several runs across the airfield without leaving the ground. When he did finally attempt a take-off run, the climb was far too steep, and even with the engines at full throttle he was unable to keep her in the air. The right wing dropped and the aircraft struck the ground with the nose and right wing. As a result of the accident Keep had sadly to have both legs amputated, but he remained with the firm in a managerial capacity. The Dreadnought episode only highlights the perils facing test pilots in those days, for there were no emergency medical facilities on hand, if one excepts the office medical box, and no crash-fire facilities.

Westland Dreadnought.

Aircraft design Air Ministry staff decided what was required in terms of materials used, structural integrity, weaponry and performance, and air specifications were issued to competing firms. There follows an aircraft specification typical of the inter-war years. Sending prototypes to Martlesham, if a land plane, or Felixstowe, if a seaplane, for evaluation and testing was by 1924 standard practice. Performance checking was the responsibility of Captain R.N. ‘Loopy’ Liptrot and his small Air Ministry staff at Kingsway in London. Structural integrity was the responsibility of Frank Cowlin, Head of Airworthiness at RAE Farnborough. At this time there were only a few books of reference to guide aircraft designers, such as Bairstowe’s Aerodynamics and Pippard & Pritchard’s Aircraft Structures. Apart from books such as these there were only standard engineering textbooks. There were no special instruments, no strain gauges and no electronics. A hand-held spring balance was the usual instrumentation by which a pilot brought back confirmation that the controls were too heavy, and the phases of instability were measured by a stopwatch. Although wind-tunnel testing was to be developed during the inter-war years, most firms would have to use the one at the National Physical Laboratory. But because aircraft were of a simpler design and manufacturers’ design teams were small, they could work much faster. Only eleven months, on average, was necessary from inception to the first flight of the prototype. The more determined manufacturers, who were convinced of the worth of their designs, like Fairey, would undertake private ventures in an attempt to prove that the Air Ministry specification was outmoded. To give an indication of the performance qualities of an aircraft that had to be ascertained during test flying, the following are extracts from a typical Air Ministry specification for a bomber aircraft between the wars:

Contractor’s flight trials

- Diving These must include the following diving tests – the aircraft must be dived to an indicated air speed 50% in excess of that attained in level flight at maximum rpm at rated height, or to the speed that can be reached without the engine exceeding that which is allowable. The diving tests are to be made under the following conditions:

- a)Full service load which gives the aftermost CG [centre of gravity] position at full load.

- b)Reduced load with CG at the aft limit of the basic range extended aft by 10% of that range.

- c)The dives are to be made with throttle settings as follows:

- i) One dive with loading as per sub-paragraph a. with throttle setting corresponding to full power.

- ii) Dives with loads as per sub paragraphs a. and b. with throttle setting corresponding to one-third power.

Each dive is to be commenced with the aeroplane flying horizontally at its maximum speed and trimmed to fly elevators free at that speed. The throttle is then to be set to the desired position and the aircraft dived until the limiting speed as defined above is attained. The tail setting is to be maintained in the dive unless the force required on the control column becomes excessive. During the dive at the maximum speed each control organ is to be moved through small angles to test its effectiveness and to detect any tendency to excessive oscillation.

- Performance, stability and control

- The maximum speeds at altitudes of 5,000 feet and 15,000 feet are to be not less than 195 mph and 205 mph respectively.

- The time taken to reach 15,000 feet is not to exceed 20 minutes.

- The service ceiling is to be not less than 25,000 feet.

- The aircraft shall be able to keep at a height not less than 10,000 feet with one engine out of action.

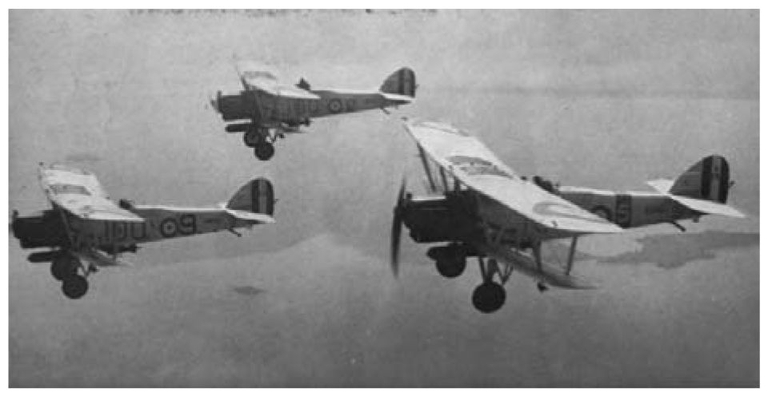

The Grebe and Gamecock In 1923 a replacement for the Snipe on fighter squadrons was being actively considered. Larry Carter had flown the prototype Grebe that year in the King’s Cup Air Race. The Grebe had a Jaguar III engine and could carry four 20 lb bombs under each wing. It was deemed both a day- and a night-fighter, and 132 were bought for the service. Its outstanding characteristic was its manoeuvrability, having ‘harmonized’ controls, and was a great favourite with pilots. For the Gloster Aircraft Company the Grebe contracts were the first real evidence of the new policy of expansion to provide new squadrons for home defence. Yet again the Air Ministry was mindful of the need to keep feeding work to firms other than the one that might be successful in the competitive bid. In securing the contract to build the Grebe, Gloster was required to subcontract the production of wings and tail units to de Havilland, Avro and Hawker. Bristol, under the direction of Mr Roy Fedden, had developed a new radial engine, and induced Gloster to incorporate it into a modified Grebe: this became the Gamecock. With an extra 100 hp, the RAF was pleased to order ninety of these aircraft.

Gloster Grebe.

Gloster Gamecock.

Radial or water-cooled engines Contemporary aircraft of the day had either radial or water-cooled engines. The radial engines could be cowled, but were often open, leaving the cylinder pots exposed to the air, and were thus air cooled. The water-cooled engines required a large, bulky radiator. The result was either the exposed frontal bulk of the DH9A radiator, or, if the radiator was enclosed in metal, the unstreamlined appearance of an Aldershot or Fawn. The chairman and managing director of Fairey Aviation Ltd, Mr G.W. Hall FRAeS, was so impressed with the performance of the Curtiss D12 racers in the 1923 Schneider Trophy seaplane races that he proposed to the Air Ministry a two-seater bomber that was faster than any single-seater fighter of the day. Given Trenchard’s view that success in war lay in offence, not defence, this should have been appealing, but his proposal was rejected. So Mr Hall embarked upon a private venture, sailed to the USA and came back with the rights to the Curtiss engine, the Read propeller, wing surface radiators and various other design features. Fairey could now build a light bomber with a small frontal area, giving an elegant streamlined appearance. This was to be the Fairey Fox.

Fairey Fox.

Armstrong Whitworth Siskin The Siskin continued the trend towards all-metal construction. Although marginally inferior in speed and range, it was regarded as a safer aircraft than contemporary ones of its type. The conversion from composite wood/metal structures to all-metal ones was gathering pace. Gloster obtained shares in the Steel Wing Company, a firm dedicated to all-metal construction since 1919.

Armstrong Whitworth Siskin.

Inadvertent stalling One of the major problems confronting designers and pilots in 1924 was inadvertent stalling. Normally this occurs when the pilot raises the nose of his aircraft, as in a climb, but with insufficient power to maintain that climb. Eventually the aircraft suddenly loses lift and the nose drops abruptly, so that the aircraft is put into a dive. If an aircraft has sufficient height the pilot can pull out of the dive, but in some cases this can be dangerous, if not fatal. If the stall occurs close to the ground the aircraft may crash before the pilot can recover from the dive. Even if the stall occurs at a safe height the aircraft may go into a spin. Since some fifty lives were being lost in the RAF each year through spinning accidents, the matter was a principal concern of RAE Farnborough, and the pilots there were making spins with different aircraft types to assess the factors involved. One answer was to incorporate Handley Page slots into the wing of an aircraft, but the variations of slot were complicated and difficult to adopt.

1924 developments in design Before the year’s end several interesting developments in design had taken place. Bristol had tested the all-metal cantilever wing. Hawker proved that strict weight control paid dividends and Short showed that shapely and strong fuselages could be fairly simply made using duralumin monocoque. Finally Westland’s use of full-span combined aileron and flap meant complications in attaining full lateral control.

1925

The year 1925 was one of considerable activity in the development of aviation in general and military aviation in particular. With the RAF expansion plan in place, albeit spread over an indeterminate number of years, Trenchard and his staff at the Air Ministry could begin to replace outdated types and place orders to equip the new squadrons. This included significantly the Special Reserve and auxiliary squadrons, the introduction of which was described in Chapter 3. The new types were to go to the home-based squadrons. Paradoxically the RAF squadrons employed operationally during the 1920s in India and the Middle East were equipped with the Bristol F2B and the DH9A, both First World War aircraft. But these two aircraft, previously a fighter and a bomber, were of simple design and able to withstand the rugged terrain, the intense heat and, in India, the paucity of spare parts, some of which had to be manufactured locally. Their employment in air policing resulted in their being classified ‘general-purpose’ aircraft, as were those that were to follow, like the Wapiti.

Further company developments With the demands placed upon the aircraft industry increased because of the RAF expansion plan, companies sought increases in manufacturing capacity. With the rise from eighteen to fifty-two Home Defence squadrons, design teams were busy. A.V. Roe kept his design and experimental staff at Hamble but purchased 163 acres of land at Woodford for a new airfield from where he could operate aircraft away from the industrial haze of Manchester. The large hangars taken from the vacated airfield at Alexandra Park were reassembled at Woodford. In them aircraft were reassembled after manufacture in Manchester. Similarly, Armstrong Whitworth had separated design and testing facilities. The design staff remained at the original office in the Parkside works, Coventry. A flying school was established at Whitley with facilities for testing experimental aircraft. The company’s aircraft production shops were also moved there. One of the aircraft being work on at that time was the Atlas, a two-seater Army Cooperation machine that was then still on the secret list.

Aircraft Disposal Company The Aircraft Disposal Company (ADC) still represented a threat to the struggling firms in the industry that could have sold spares to the purchasers of war-surplus machines. By 1925 the ADC had disposed of millions of pounds’ worth of stocks, thereby repaying the government £1.25 million exclusive of taxation, and their premises at Croydon were larger than those of any other aircraft manufacturer. Sales included Scarff rings, bombsights, machine-guns, reconditioned engines and other spares. This service was particularly useful to countries that could not afford expensive armaments. Significantly the Air Ministry ordered one hundred DH9As with the Liberty engine in 1925. Their rugged qualities made them particularly suitable as general-purpose aircraft in Mesopotamia and India.

More Prototypes

A wealth of types from a wide range of companies came on the scene in 1925. Before naming the individual aircraft, the biplane versus monoplane debate is further considered. Flight Magazine in 1925 published an article saying, ‘We do not think that the marked superiority of the monoplane over the biplane in such large machines has yet been conclusively established and we believe that the future will show room for both.’ The fate of the Westland Dreadnought certainly showed that there was much work to be done, and so it was that most of the new aircraft coming on stream were biplanes.

Fairey Fox The prototype Fairey Fox was first flown by Norman McMillan at Hendon on 3 January 1925. Although a two-seater day-bomber, it was 50 mph faster than the Fairey Fawn. This was the fruit of importing design features from the USA, resulting in a streamlined appearance. The aircraft was demonstrated at Northolt in October 1925 in front of Trenchard and Geoffrey Salmond. Speed and the aerodynamically clean appearance appealed to Trenchard with his view about offensive defence. Fairey was also building a single-seater version called the Firefly. But orders for the Fox meant importing £60,000 of American engines, since no British engine was available at this time. Accordingly only one squadron was equipped with this aircraft.

Gloster Grebe, Gamecock and Gloster II In February Larry Carter flew the Gloster Gamecock fighter to Martlesham for test and evaluation. It was a Grebe with a Bristol Jupiter engine. He also flew the Gloster II at Cranwell with a Napier Lion engine uprated to 700 hp at 2,700 rpm. The intention was to make comparative tests on several metal propellers, radiators and so on. Carter fractured his skull and broke a leg when he had to make an emergency landing at 200 mph that carried away the undercarriage. Tail flutter had developed while he was flying at 40 feet above the speed course, but as the cause and the cure seemed apparent, work on the Gloster IIIA and the Supermarine S4 seaplanes was pressed forward, and Hubert Broad and Bert Hinckler were selected to fly them.

Gloster II.

Armstrong Whitworth Atlas The Atlas was flown for the first time in May 1925. It was designed as a replacement for the Army Cooperation Bristol Fighter and was a twoseater, single-bay aircraft. Although smaller and stockier than the Bristol Fighter, its all-up weight was greater. Powered with a geared Armstrong Siddeley Jaguar engine the, prototype J8765 achieved over 140 mph. The test pilot, Frank Courtney, found that it had a tendency to stall sharply and the ailerons were too heavy. Moreover it had a tendency to drop a wing on landing. Nevertheless, production between 1926 and 1933 totalled 450, including trainers.

Armstrong Whitworth Atlas.

The Westland Bomber This aircraft was test-flown and found to be satisfactory on its maiden flight. Frank Courtney was brought in to test-fly the bomber for a fee of £100. Although Westland’s new test pilot, Major Lawrence Openshaw, was available, his services were not used on this occasion, as he had been absent from test work for some time.

Westland Bomber.

The Bristol Berkeley and Bloodhound The Bristol Berkeley arrived at Martlesham on 5 March 1925. This had a nose cockpit, affording the pilot an excellent view forward, but the Martlesham pilots preferred the aft cockpit of the rival Westland Bomber and the Handley Page Horsley. Bristol had little better luck with its Bloodhound, as the constructional system of fabricated steel was considered impractical.

Bristol Berkeley.

Bristol Bloodhound.

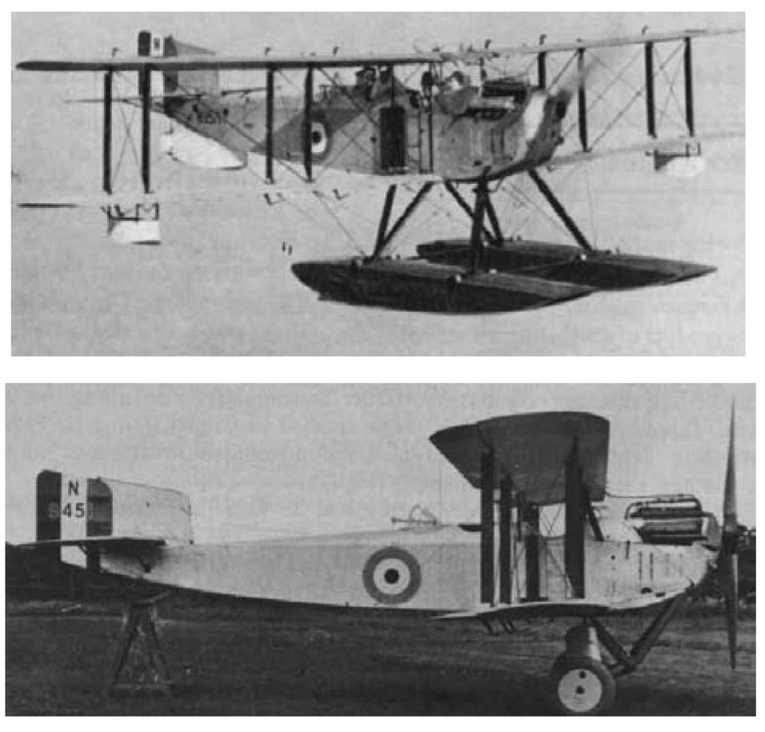

Supermarine Southampton The prototype N218, built to Air Ministry Specification 18/24, was well received by the RAF test pilots and showed the trust which the Air Ministry had in the work of R.J. Mitchell, the designer of the Spitfire. Such was the trust that six were ordered by the RAF from the drawing board. The prototype Southampton was first flown on 14 March 1925. Since no modifications were deemed necessary, the seaplane was handed over to the MAEE (Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment), the seaplane equivalent of Martlesham, on 15 March 1925. The Southampton was a significant advance on the wartime-designed Felixstowe F5. The uncowled engines and gravity-feed tanks were good from a mechanic’s point of view, with the tanks located under the top wing to reduce the fire hazard The height of the propellers above sea level matters in high seas, and the only criticism that could be levelled at the design was that the propellers could have been higher.

Supermarine Southampton.

Short Singapore Oswald Short did not get the contract for the seaplane to Air Ministry Specification 13/24 with his all-metal Condor-powered flying-boat, and so he telephoned Sir Geoffrey Salmond to say that he was going to build the aircraft even if it made him bankrupt. Thereupon Salmond went the next day to see the seaplane for himself. Oswald Short got the contract, and this was to be the Short Singapore.

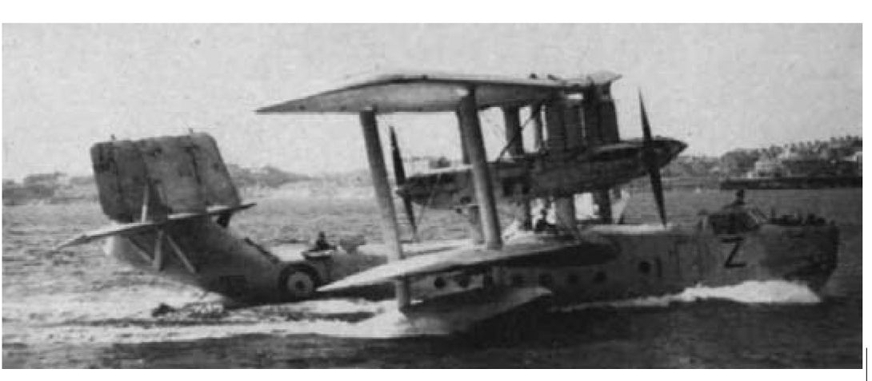

Short Singapore.

Hawker Horsley The Horsley was a rival to the Westland Bomber, but the test flight by George Bulman was disappointing, for the aircraft was longitudinally unstable and the cooling system with radiators each side of the fuselage just ahead of the pilot was useless. This was remedied by fitting a single radiator below the nose, but the instability was intrinsic in the modified Gottingen thick aerofoil chosen because of its high-lift coefficient and to enclose the fuel tanks within the contours of the aircraft. By repositioning the radiator the centre of gravity was brought forward, which improved matters, but ultimately sweep-back had to be incorporated into the wings. Eventually this aircraft was accepted as a day-bomber by the RAF.

Hawker Horsley.

de Havilland Moth de Havilland’s Moth was an important addition to the list of inter-war prototypes. A dual-control trainer, it was a ‘must’ for the country’s flying clubs and could provide valuable experience for those air-minded men who would eventually join the RAF. The prototype G-EBKT was first test-flown on the afternoon of Sunday 22 February 1925 at de Havilland’s Stag Lane aerodrome. Geoffrey himself flew the aircraft, which was airborne in just 100 yards. When he landed Hubert Broad joined him for a second flight and to try the dual controls. The aircraft performed well and both men were well pleased. Even in the waterlogged state of the airfield the Moth took off quickly and climbed well. It had enough stability to fly hands off. Initially the prototype’s rudder had no balance, and foot pressure was necessary to hold directional trim, but this was remedied. Production machines were to sell at £900.

de Havilland Moth.

Wood construction again The debate about wooden construction was revived by old Dick Fairey of Fairey Aviation, insisting still that aircraft should be constructed of wood, even though the Air Ministry wanted his Fairey IIID to be of metal construction, for the termites simply loved the wood and fabric of Fairey seaplanes abroad. While Dick Fairey was away in France convalescing from an illness, Colonel Nicholl signed a works order for a metal version. In the event a great deal of the aircraft’s construction was changed – it was not simply a conversion of wooden to metal parts.

Aero engine development Napier was doing well and turned in the highest profit in the firm’s history. The figure for the financial year 1924/5 was £237,542. Montague Napier was none the less concerned that the Cub engine, which was set to replace the Lion, would only have a limited future. He felt that the firm should branch out into air-cooled engines but knew that Armstrong Siddeley and Bristol already had a five-year lead. Radials were air-cooled, and since the engines were externally mounted, they were easier to service, and Trenchard favoured their practical merits and simplicity for fighters. On the page below are the silhouettes of three contemporary aircraft showing that the bulk of radiators inside the contours of an aircraft, such as the unstreamlined Fairey Fawn, compared unfavourably with the Fairey Fox with its streamlined appearance. The aircraft with radial engines combined ease of access and the simplicity of design that obviates the need for radiators with an element of streamlining. Then there was the question of engine reliability. The Aldershot was designed as a single-engined heavy bomber and fitted with a Rolls-Royce Condor. The larger the aircraft the more difficult it would be to put down in a field in the event of engine failure. In future all heavy bombers were to be multi-engined, and for this reason the Blackburn Cubaroo was rejected.

THE EFFECTS OF AIR AND WATER COOLING OF AERO ENGINES UPON STREAMLINING

1926

Air Ministry Orders and Specifications In 1926 the government still backed the biplane. This caution was in part explained by the unfortunate post-war experience with monoplanes. Hawker, the firm that was to produce the Hurricane in the mid-1930s, had the Jupiter turned down for this reason. The Air Ministry policy of placing competitive orders with two or more firms for aircraft had become firmly established. The Atlas was in competition at Martlesham with the DH56 Hyena, the Bristol Boarhound, which had been at Martlesham since the summer of 1925, and the private-venture Vickers Vespa, which had first flown in September 1925 and was delivered to Martlesham in civil guise. To obtain the requisite low landing speed these prototypes would all, save the Atlas, have wings approaching 45 ft span. The Hyena was a redesign of the all-metal DH42B Dingo III to overcome the deficiencies of the pilot’s view, so his cockpit was now in line with the trailing edge of the wing and not under it. But this meant rebalancing the weight distribution, so the top wing was moved rearwards by raking the rear interplane struts back and swinging the front ones into the vertical. Finally the nose was extended to bring the weight of the 385 hp Jaguar forward. But better performance did not result, and a 422 hp Jaguar IV engine had to be fitted.

1926 Prototypes

The RAF in 2005 has just the Harrier, Tornado and Jaguar as strike aircraft, and the Tornado as a fighter, with only the European Fighter Aircraft on the horizon. When it comes to long-haul airliners the Boeing 747 is getting long in the tooth, and the Concorde has passed from service with nothing to replace it in supersonic service. In stark contrast, the 1920s saw the prototypes coming thick and fast. Although only a few actually reached RAF service, it is from the experience gained from all prototypes presented for RAF acceptance that the reader can follow the wood versus metal, air-cooled versus water-cooled, biplane versus monoplane debate. Indeed, several of the aircraft taking part in the 1926 Hendon Air Pageant did not see operational RAF service.

Bristol Bagshot and Westland Westbury These were two aircraft that were built to Air Ministry Specification 4/24. Since the Air Ministry was unsure about the aerodynamics of the monoplane Bristol Bagshot, a competitive tender was put out to Westland for a twin-engined biplane fighter. The expert predicted that a monoplane would be much heavier than a biplane equivalent, but this was not to be the case. The Bagshot was only 350 lb heavier than the Westbury, at 7,875 lb.

Westland Westbury.

Bristol Bagshot.

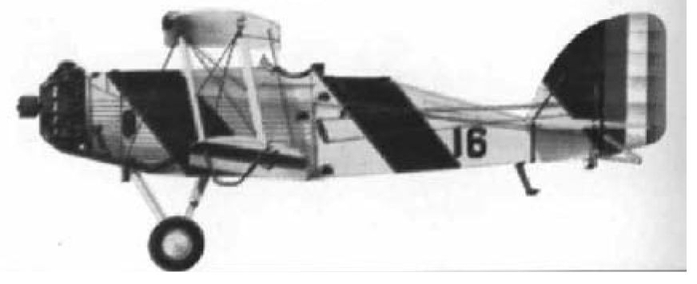

Fairey IIID The Fairey IIID had been built both as a land-plane and a floatplane. It was solid and the RAF employed it for maritime duties. It was easy to fly although it had poor lateral control when the ailerons cum flaps were lowered. It was powered with various marks of the Napier Lion engine. The reliability of this engine was proved when four IIID land-planes, led by Wing Commander Pulford, flew from Cairo on 1 March 1926 to reach Cape Town on the 12th.

Fairey IIID floatplane.

Fairey IIID land-plane.

Note: The photographs illustrate clearly that a floatplane, such as the Fairey IIID floatplane above, has basically the same fuselage as a land-plane, with the addition of floats that keep the fuselage clear of the water. (The four Fairey IIIDs mentioned above started their return flight to England as land-planes, but had floats fitted at Aboukir.) A flying-boat, however, has the hull of a boat and sits in the water, as illustrated at the bottom of page 180.

Other prototypes These included the Vickers Vendace, which was recommended as a deck-landing trainer after naval trials, the Firefly I of composite construction, which failed to get the RAF’s blessing or orders, the Avro Avenger, which was turned down by the RAF because it was felt that equipment stored in the fuselage would not be readily accessible, and the Vickers Type 121, which was that company’s first attempt at all-metal construction. When the latter was test-flown, Flight Lieutenant E.R.C ‘Tiny’ Scholfield, a giant of a man, was fortunately issued with the first Irvine parachute for civilian use. When the Type 121 got into an uncontrollable inverted spin, Tiny baled out under 2,000 ft, the aircraft crashing into the Vickers Sports Club grounds. Tiny had to walk back to Brooklands with his parachute tucked under his arm. The Blackburn Iris and the Saunders Roe Valkyrie were contenders for the Air Ministry Specification R14/24. The Iris took more than two years to build but had a metal hull. Short had shown that water-soaking wooden hulls were obsolete. The Valkyrie was equally seaworthy and was somewhat cleaner in appearance, but did not win the RAF’s favour. It seems that considerations of maintenance, such as the removal of engines and mountings, outweighed performance. Most French aircraft of the period were aerodynamically cleaner than their British counterparts. The French were more concerned with speed for both fighters and bombers, and multi-guns to drive off attacking fighters, coupled with small bomb loads to aid speed. It is interesting that the Valkyrie was test-flown by the ‘ubiquitous’ Mr Frank Courtney, who had been paid £100 to test-fly the Westland Bomber.

Blackburn Iris.

Saunders Roe Valkyrie.

Test flight of the Short Singapore This aircraft was mentioned for the year 1925. On 17 August 1926 the new flying-boat took to the water at Rochester. Lankester Parker, chief test pilot of Shorts, was at the controls, with Eustace Short as observer for this maiden flight, and all the employees came out to watch. But only a two-minute hop was possible that day, owing to the loss of an engine cowling, to be followed two days later by water leaking into the bilges, and the aircraft had to be returned to the shops for rectification.

RAF Accidents and Aircraft Safety

Compared with the accident record of civil aviation, that of the RAF can only be described as disastrous. Every type of RAF aircraft had been involved, and fifty-one fatal accidents had occurred since the beginning of the year. Fifteen of them involved Bristol Fighters and eleven DH9As. One wing commander, two squadron leaders and three flight lieutenants lost their lives, but most fatalities occurred among the ranks of flying officers who had the least flying experience. Concern over these deaths reached Parliament. Following investigations by the Daily Express, Mr Hoare Belisha, Liberal MP for Devonport, asked the Prime Minister if he would allot one day of parliamentary business to discuss the cause of these fatalities. Since most accidents involved spinning, RAE Farnborough had been working on the problem. Tests had shown that a bigger rudder on the Bristol Fighter would give immediate recovery from a spin, yet none was ordered. Handley Page Ltd had demonstrated its special wing with interlinked wing-tip slots and ailerons, but this necessitated a redesign of the wing structure. But it was cheaper to leave the Bristol Fighter as it was, for the aircraft was soon to be replaced by the Armstrong Whitworth Atlas. Be that as it may, Mr Handley Page was able to announce at his company’s AGM that the Air Ministry had directed that all MkIII Bristol Fighters in service were to be fitted with the automatic slots. The question of the effectiveness of wing and flap slots has been discussed before in this chapter. Pictured on page 181 is a Handley Page Hendon flying very slowly past the camera with its nose well up. The leading-edge slots can clearly be seen.

Under normal circumstances this aircraft would have stalled, and the technical experts at the Air Ministry were blamed for the deaths of their pilots in spinning accidents following a stall because these slots were not adopted. While the aircraft industry’s test pilots had flown the Hendon there was no rush to adopt them. Indeed, RAF pilots found that the interlinked slots and lift flaps were cumbersome to operate and caused big changes in trim. Ailerons interconnected with wing-tip slots were also stiff. All one could say was that a crash from a rapidly sinking aircraft was preferable to one that resulted from an aircraft spinning into the ground.

Other work in pursuance of aircraft safety centred on stress. In a lecture to the Royal Aeronautical Society Professor H.B. Howard, head of RAE’s airworthiness department, said, ‘The maximum loads which the structure [of an aircraft] will be called on to carry cannot be stated with certainty as they depend primarily on how the pilot manipulates his controls. The maximum he can impose is calculable but it is greatly in excess of those he uses. It is neither practicable nor necessary to make the aeroplane absolutely unbreakable at all speeds.’ One area that received particular attention was in tapered-wing monoplanes. Because of the greater simplicity of biplanes, this problem had not been given sufficient serious thought. Another problem centred on the oleo strut that attached the wheels to the wing spar. On landing the force of impact has to be transferred from the wheels to the spar. Bristol had been worried that putting twin spars in its Bagshot monoplane would cause the aircraft to be overweight.

The COW gun The retention of the well-tried and tested Vickers and Lewis guns after the First World War has already been mentioned. Cannon with greater hitting power were to come. What makes the COW (Coventry Ordnance Works) gun so interesting is that it was to fire a 37 mm shell, the gun being six feet long. The rate of fire was only 100 shells per minute, which was much slower than machine-guns of 0.303 in. calibre. Moreover, the recoil of some 2,000 lb had to be allowed for in its effects on aircraft handling during firing, not to mention the problem of mounting it in an aircraft. The COW gun did not become standard armament equipment for the RAF.

The General Strike In closing the narrative on 1926, the strides being made by the aircraft industry are seen against the backdrop of industrial unrest. Men who had served an apprenticeship to become skilled workers could earn, in 1926, only £3 per week, compared with, say, a railway porter, who could earn £4 plus tips. But aircraft workers were employed in work of an exciting nature at the cutting edge of technology. With high job satisfaction, most of those who did not join the General Strike were non-unionized, and London district aircraft firms Fairey and Hawker had 50 per cent and 60 per cent respectively who stayed at work. The strike had been brought about by the Triple Alliance of miners, dockers and railway workers, and the strike at national level lasted only nine days, the TUC calling it off on 12 May. The miners held out for another six months, losing a further £60 million in wages, a sum, collectively, that they would never make up.

1927

State of the aircraft industry The General Strike had not touched the aircraft industry as much as the older traditional ones such as mining, the railways and ports. Job satisfaction in working with aircraft certainly contributed to the lack of involvement in industrial strife, but industrial patterns were changing. Workers were migrating from the industrial and depressed areas of the north of England to the London area. London, on the periphery, was growing with heavy industries, including petroleum refining, chemicals and textiles, and Ford at Dagenham in the Thames estuary, as well as light industrial firms like Hoover in north London. With the expansion came council housing estates and ‘ribbon’ development along the roads leading out of the capital. But the aircraft industry served a much smaller market. Only the rich could afford to purchase aircraft, and relatively few could afford to travel by air. These were the days before package holidays when, as now, the mass public flies all over world. Add to this the very meagre expansion of the RAF and one can imagine that it made little sense to have sixteen major airframe builders and four engine makers. From the RAF’s point of view, however, a change in the international situation could require the industry to expand production with little warning, as indeed happened in the mid-1930s. Then it was necessary to bring in the car makers to assemble airframes and engines to meet the surge in demand. For the single-minded pioneers of flying this was not a problem. They were involved in producing designs to meet Air Ministry specifications, followed by yet more designs, more prototypes and more test flying. Hence the large number of aircraft that fill these pages. One hundred and fifteen separate aircraft of all types equipped RAF squadrons between the two world wars. The French aircraft industry had even more capacity, with thirty-six aircraft manufacturers and ten aero-engine makers. They too needed an annual appropriation of state funds spread thinly over the whole industry, and this was used mainly to fund experimental aircraft.

Developments in aircraft component design Squadron Leader G.H. Reid DFC, inventor of the aircraft turn indicator, had formed the Reid Manufacturing and Construction Company Ltd to market this and other devices on his retirement from the RAF. There were also developments in the design of aircraft superchargers. Experimental work on superchargers began during the latter stages of the First World War, but no great advances had been made. Folland was cooperating in trials of a Bristol turbo-supercharged Jupiter engine, but the system proved to be too unreliable. In France and the USA work on exhaust-driven turbo-compressors had been undertaken, while in Germany and Switzerland research had centred on gear-driven multi-stage superchargers. The problems associated with systems driven by exhaust gases were explained by Roy Fedden on 1 February 1927 to a meeting of the RAeS and Institution of Automobile Engineers. Turbine wheels and casings with rotors running at 27,000 – 30,000 rpm in exhaust gases at 650 – 700 degrees C had to be manufactured. The problems that arose involved exhaust joints that were not gas tight, the effect of blowers on crankshaft, synchronous speed, the reduction of thermal efficiency and the difficulty of engine and gas cooling. There were also snags with lubrication. Fedden’s prognosis was that ground-boosted gear-driven blower engines of a smaller capacity should replace the naturally aspirated engines currently used in fighter aircraft. For larger, general-purpose machines he pointed the way to supercharged engines throttled on the ground but opened up to full power at some predetermined altitude. Exhaust-driven turbo-compressors were more suitable for high-altitude, long-distance bombers where fuel consumption was vital. But Farnborough’s ‘Jimmy’ Eltor was convinced that supercharging would become practicable much sooner if designed around the principle, instead of trying to accommodate the principle to a design intended for naturally aspirated engines.

1927 prototypes

The Wapiti The Westland Wapiti, a general-service aircraft destined to take over as the work horse in the imperial policing role, made its initial flight, piloted by Openshaw. The Wapiti was a derivative of the tried and tested DH9A, using its standard wings and control surfaces. After the maiden flight on an early Sunday morning, Openshaw reported that there was little response from the rudder. Clearly a deep fuselage can have a major effect by shielding the rudder from the airflow, so extra plywood was added, which, however, did not produce the desired effect. A very large rectangular rudder was fitted, but this was disproportionate to the fin. The aircraft was nevertheless favourably received by the Martlesham test pilots.

Westland Wapiti.

The Fairey Postal The RAF planned to take the record for a long-distance flight, and Fairey learned of this project through Squadron Leader Carr, a friend of Air Marshal Sir John Higgins, who decided that a special aeroplane must be built to establish a prestige lead over the French, Italians and Americans. Fairey set out to build a high-wing monoplane with a fixed undercarriage, named the Postal. The idea was to provide the best possible lift and drag component and fly at the most economical cruising speed using a special Napier Lion engine. Fuel consumption was promised at .52 pints/bhp/hour, but the cruising speed was only 25 per cent above the stall. It was presumed that high ‘g’ would be avoided with low-strength factors to give a light structure. Add to this a hoped-for tail wind, and it was felt that the record could be broken.

New orders for the aircraft industry As a result of the accidents previously mentioned involving Bristol Fighters, Handley Page was to profit from an Air Ministry order to fit automatic slots to the wings of these aircraft to lessen the likelihood of stalling. The value of the related patents was put at £75,000. By this time Handley Page had become a well-established company. During 1927 all loans had been discharged; assets totally unencumbered and trading profits maintained. Likewise Supermarine had done well from profitable orders, and early in 1927 was registered as Supermarine Aviation Works Ltd, with capital of £300,000. The work in hand meant that its original sheds were too small, and since the Southampton flying-boat was being constructed, the wartime assembly shops on Southampton Water belonging to May, Harden and May were taken over.

Aircraft Production Orders

On the whole the aircraft industry was busy in 1927, although there were some firms that were struggling. The situation for the Bristol Aeroplane Company was becoming critical, as it only had overhaul contracts for the obsolete Bristol Fighter. A production order was badly needed, and the Bulldog fighter was a strong possibility. Beardmore, Parnall, Saunders and Short were all short of production orders, but the design staffs of these companies were not idle. Bill Shackleton at Beardmore was busy on a 140 ft wing-span all-metal aircraft, Knowles at Saunders was designing a fighter and a simplified flat-sided metal hull for a standard Southampton superstructure, and Short had in mind a four-engined version of its Singapore flying-boat. Armstrong Whitworth had full production lines with its Siskin fighter and Atlas Army Cooperation aircraft. Avro, believe it or not, was still building 504Ns at its Manchester, factory while Blackburn was working on an experimental contract for three Iris flying-boats to Air Ministry Specification 31/27, Boulton Paul had six Sidestrand bombers on the go and de Havilland was turning out its Moths. Fairey was busy producing the IIIF, which differed from the prototype in having rounded fins that shielded a balanced rudder. Gloster was producing Gamecock fighters, Handley Page its Hyderabad bomber, Hawker the Horsley and Supermarine the metal-hulled Southampton. Finally, Vickers was busy with Victorias and Virginias, while Westland was building Wapitis.

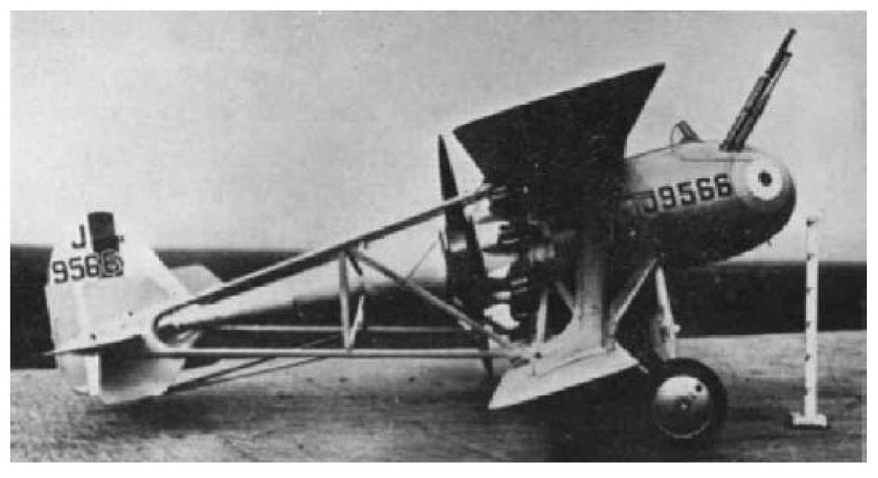

Air Ministry Specification F9/26 called for a fighter, and both Blackburn and Westland had produced prototypes. The Blackburn machine was designed by B.A. Duncan. It was deemed capable of 200 mph at 15,000 ft using a supercharged Mercury engine. Since the Air Ministry performance estimator could not accept these figures, the tender was not accepted, yet Blackburn’s private-venture Turcock, powered with a supercharged Jaguar VI, was tested on 14 November and achieved a speed of 176 mph.