Chapter 10

Air Doctrine,The Air Ministry and Command of the Air

Development of air doctrine, 1919 to 1929 – The organization of the Air Ministry – Air Ministry developments and business –

Air commanders and the quality of command

This chapter explores both the development of air doctrine and the quality of command during the 1920s. This necessarily involves a close look at the senior commanders of the RAF, both in the Air Ministry and in operational commands. The problem for Trenchard and his subordinates in developing air doctrine from 1919 onwards was that in creating an independent service they were breaking free from their own past experience and stepping into the unknown.

In developing strategic air doctrine alone, the Air Staff had precious little to go on. Trenchard himself had commanded the Independent Bomber Force for only a few months in 1918, to be converted from a tactical air commander to an exponent of strategic bombing. Even General Smuts, in making the case in his 1917 Report, which resulted in the formation of the RAF the following April, looked at the capacity of the Germans to bomb London and not the RAF’s bombing of industrial and military targets in Germany. What followed in the early 1920s was a doctrine based more on speculation than experience. For all Trenchard insisted on a policy of offensive defence, not one squadron of four-engined HP V/1500 bombers survived the First World War. And when the time came to introduce the first postwar bomber into RAF service, it was the single-engined Aldershot. The four-engined successors to the HP V/1500 were the Sterling and Lancaster of the Second World War, and so an air force committed to carrying a future war to an enemy’s homeland to destroy his industrial and military targets was obliged to conduct air exercises in the late 1920s with single-engined biplane bombers carrying a crew of two and bombs slung beneath the wings.

Operational experience during the inter-war years was of little help in developing doctrine for an air force which could find itself pitted against the forces of a developed nation using the latest designs of military aircraft. Instead, the commanders of the RAF in the Second World War were reared on punitive operations against primitive tribesmen in Iraq and India, the Sudan and Palestine. Since there was no threat from enemy fighters, the RAF’s fighter squadrons remained at home. Since no strategic bombing operations were carried out nothing was learned here. All the RAF needed was a general-purpose aircraft, and the left-overs of the First World War, the DH9A and 10 and the Bristol Fighter, were adequate for the task of air control.

By 1919 the RAF was just one year old, it was fighting for survival and it had only four years’ experience of military aviation to draw upon in the field of tactical battlefield support and cooperation, air defence of the home base and maritime reconnaissance and strike, but less than one year of strategic bombing operations. The earlier chapters of this book have forgiven Trenchard for overstating the case for the strategic employment of airpower. In Appendix Q appears correspondence between the Secretary to the Committee of Imperial Defence and the CAS, in which Hankey attempts gently to tone down some of the more extravagant claims that Trenchard was making for the efficacy of the strategic bombing offensive. But then, he was bound to make a case for a force that alone could conduct military air operations if the RAF was to survive as an independent service. Be that as it may, it was hardly fertile soil in which to plant the seeds of a reasoned and carefully thought-out air doctrine.

The Beginnings of Air Doctrine

Even before the commencement of hostilities in 1914, Frederick Sykes, the future Chief of the Air Staff, came to the conclusion that the classical principles of war did not apply to airpower. Could, he asked, aircraft win command of the air by a defeat of the enemy forces in being? Aircraft would never be able to obtain and maintain control of the air space as naval forces could obtain command of the sea, or land forces capture and hold ground. Since the air was a three-dimensional battle arena, finding aircraft, let alone bringing them to battle, meant that the ‘big battle’ could not be fought unless both sides sought to meet. In the days before radar it would be extremely difficult to be sure of intercepting an aircraft before it reached its target. This did not mean that pilots should not engage in combat if they met enemy aircraft, but when the First World War started aircraft were not equipped with guns save the side-arms of pilots or observers, and the military men saw them as auxiliaries helping Army commanders in the field or fleet commanders in the Navy, but there were some who saw a wider role for aircraft, given their speed and range. It was argued that aircraft should not be risked in a fight if they could proceed to some other, perhaps more important, objective. In 1916 Zeppelin airships, then Gotha bombers in 1917, could carry the war to the enemy, so aircraft would be needed for defence, which in turn would mean deciding on the proportion of aircraft and airships that should be committed to defence and offence.

The builder of the first British petrol car, F.W. Lanchester, joined the ranks of those with a view on the role of the military aircraft. He believed that while some components of the air force should fight the tactical war in direct support of the land forces, other aircraft should be free of the indecisive fighting on the Western Front and have the sole task of destroying all the enemy’s aircraft and so be invulnerable to challenge. While accepting that some aircraft might be detached to attack targets remote from the battlefield, the maintenance of an air umbrella over the battlefield was the primary task, and in that sense aircraft might be the Army’s fourth arm, co-equal with the artillery, cavalry and infantry. Domination of the sky could only be local and temporary. Only the troops on the ground could hold ground or ships hold a sea area. Supporters of the tactical employment of airpower said that aircraft could not achieve command of the air nor hold ground, therefore the application of airpower could never be decisive in war. The defeat of the enemy’s armed forces remained the leading principle of war, to which airpower could only contribute. Ground battles and campaigns could be decisive, but Sykes disagreed. Because aircraft could detach themselves from the deadlock of the Western Front and fight independently they could prove decisive. When Germans used Zeppelins, and then Gothas, on bombing raids against Britain, Field Marshal Haig was bound to detach aircraft from the Allied war effort on the Western Front to defend London.

Where did this leave Sykes and Trenchard, the two leading players? Sykes believed that an independent bombing force should not suffer the fate of the land armies that had been locked in an indecisive struggle across ‘no man’s land’, where thousands of lives had been sacrificed for little gain in territory. A large air space could be exploited to avoid an attritional campaign, and strategic air units would avoid enemy contact to attack economic and industrial targets remote from the battlefield, and in so doing, break down the enemy’s morale. Sykes’s aim was to follow a policy of strategic interception, that is to say maintaining a tactical presence while reserving units to prosecute the war independently of the land war. But the commander of the Independent Bombing Force, Hugh Trenchard, had found that it was essential to come to grips with the enemy air force. Of the 543 tons of bombs dropped by his force, 220 tons had been aimed at enemy aerodromes. Air fighting was essential if local air superiority was to be obtained, and then it would only be temporary unless contact with the enemy was maintained. Trenchard, having had the day-to-day responsibility to prosecute the air war in Western Europe, saw his force as contributing to the success of Haig’s armies. Sykes, on the other hand, could perhaps afford to take a more detached view. He did not believe that, should the Allied armies be successful in ending the stalemate of the trenches to break out into open country, the whole of the British air effort should immediately be thrown into the land battle.

At what point did the pursuit of a policy of strategic interception become the pursuit of strategic independence that would produce an independent air force with its own strategy? The dilemma would not go away by simply creating the RAF. The CAS and his staff at the Air Ministry would still have to decide what proportion of the air effort should be devoted to tactical air operations and what proportion to strategic bombing operations. There again it is ironic that the Smuts Report of 1917, which brought the RAF into being the following April, was directed at the disjointed attempts by the two services to defend London against bombing attacks by German Gotha aircraft, and it was again the air defence of the United Kingdom in 1940 that was the first major air battle of the Second World War. The Smuts Report was saying that the air war can be most successfully prosecuted, and waste through duplication of effort avoided, by a unified air service. However, when Trenchard assumed command of the RAF in 1919 he was to become the outspoken advocate of offensive defence, of carrying the war to the enemy, and for that there must be an independent air force. It was now left to him and his subordinates at the Air Ministry to formulate post-war air doctrine. The following paragraph itemises the factors that had to be taken into consideration, and these may be found useful in exploring the development of air doctrine.

Factors Affecting the Formulation of Air Doctrine during the early 1920s

The anticipated enemy or benchmark State Previous chapters have shown that France was the anticipated enemy. Or was the French Air Force simply being used as a benchmark, i.e. was France simply the country with the largest air force within striking distance of the shores of Great Britain? If so, the strength of the French Air Force and the qualities of its military aircraft had to be the benchmark.

The ‘Ten-Year Rule’ and disarmament For military planning purposes the government promptly declared the ‘Ten-Year Rule’, in that no major war affecting Great Britain could conceivably be fought for at least ten years. That figure was to be reviewed each year and carried forward or altered if circumstances changed. This was to be coupled with the creation of the League of Nations, when members of the League would pursue a policy of peace and disarmament.

Experience of the strategic employment of airpower during the First World War The German Air Force had used Zeppelins and Gotha bombers against the United Kingdom, and the RAF’s Independent Bombing Force had made forays against enemy targets behind the lines and against communications and economic and industrial targets The largest bombers used by the RAF were the twin-engined HP 0/100 and 0/400 aircraft. No experience was gained using the HP V/1500 against targets in Germany from bases in the United Kingdom. In other words there was not a wealth of experience in this field.

The indivisibility of the air This meant that airpower was exercised in one element, i.e. the air, whether the forces were being employed in strategic or tactical attack, air defence, reconnaissance or on maritime operations. The exercise of airpower was therefore a matter for an air force.

The concept of offensive defence While thought must be given to the proper air defence of the home base, the best way of ensuring the safety of the British Isles was to carry the war directly to the enemy and so incapacitate him, break his morale and get him to sue for peace.

RAF support to the Army and the Navy The appropriate air units should be made available to give direct support to the land forces and to naval forces afloat. Land-based maritime forces would also assist the Navy within shore range. Agreement was to be reached between the RAF and the Army and Navy as to what were the appropriate force levels and the type of aircraft to be used and the manning of such aircraft. This matter was to give rise to considerable dispute between the RAF and its sister services.

The aims of strategic bombing This was another area where there was a great deal of argument, particularly between the three service heads, always involving the government of the day. Would it be the aim for the RAF to win the war without the help of the other two services, and if not what degree of collaboration, joint planning and joint decision-making was thought to be necessary? Was the aim to break enemy morale to win and if a knockout blow was not to be inflicted on the enemy was the nation prepared and equipped to fight a long war of attrition? In any case what constituted winning a war?

Acceptable attrition rates If the RAF was to be forced into a future war of attrition it would need to calculate what aircraft losses it could sustain and what would be the capacity of the aircraft industry to replace those losses. The only way of answering that question was through air exercises, imprecise as the answers might be. Coupled with this would be the capacity of the RAF to replace losses in personnel, which is why a well-trained Reserve was so important. These points will be considered further in exploring the development of RAF air doctrine, but the reader may already be finding that the debate can get bogged down in jargon, something the author has been anxious to avoid, and so to make it easier to follow the ongoing debate a few terms are defined as follows:

Counter-Force Operations These refer to air operations against an enemy’s aircraft in the air and his airfields, aircraft-carriers or warships.

Strategic Air Operations These are air operations completely divorced from the battlefield area, being aimed at the enemy’s communications and economic and industrial targets.

Tactical Air Operations These are air operations confined to the immediate battlefield and rear areas, i.e. enemy supply and reserves behind the front line.

Strategic Interception These are air operations that comprise both counter-force and purely strategic air operations.

Air Superiority This occurs when an air force has a clear superiority in air fighting capability that enables that air force to undertake operational sorties with little prospect of enemy interference. Air superiority in this sense is probably local and may be temporary.

Air Supremacy This occurs when all enemy air opposition has been eliminated, so that there is no prospect of enemy air interference. As a matter of interest, this is exactly what the RAF and US air and naval air forces were seeking to achieve in the elimination of all Taliban air forces in Afghanistan.

Command of the Air This is General Douhet’s air theory about winning the air war, but there is some doubt as to whether this simply means achieving air supremacy or includes the complete destruction of an enemy’s capacity to produce any more aircraft or air weapons.

Air Doctrine in the Immediate Post-war Years

In his book British Air Strategy between the Wars, Malcolm Smith joins most other commentators on Trenchard’s ability to define in writing what he meant. He had been described as a being like a ‘Pole star’ in his knowledge, but was so inarticulate as to need younger, able staff officers to assist him to put his thoughts into words, people, that is, like Arthur Harris and John Slessor. The thoughts of the great man in 1919 seemed to have hardened and, some may think, narrowed, to an adoption of a doctrine based upon offensive defence. The question is – did Trenchard insist upon the strategic offensive as the most important role for the RAF simply because it was the one role that could only be carried out by an independent air force?

Having spoken of the indivisibility of the air, Trenchard was not prepared to divorce the tactical use from the strategic use of airpower. Slessor spoke in much more flexible terms. The whole point about the employment of airpower was its flexibility and mobility. Aircraft should be used wherever and whenever circumstances dictated they could be used to the greatest effect in furtherance of war aims. If he did try to separate the tactical from the strategic, Trenchard risked the Army and the Navy reclaiming their own air components. The problem with the ‘indivisibility’ approach, however, was that it left a great deal of leeway to planners and commanders in the field to interpret the situation in whatever way they pleased.

The morale effect of strategic bombing Returning to the strategic use of airpower, we find Trenchard saying that it was far better to bomb the enemy in his homeland than to intercept his bombers coming in. On the other hand he seems, at times, to put the morale effects of bombing before the material effects, and he was much criticized for overstating the case for the former (see Appendix Q). Malcolm Smith argues that Trenchard was fond of using the unfounded statistic by placing the morale effect against the material effect of bombing at a ratio of 10:1. Were civilians so prone to panic as the Jews of the East End were reputed to be during the 1917 Gotha attacks on London, or would the French ‘crack’ before we British did? Some military writers went so far as to suggest that paramilitary discipline should be instilled into the civilian population to ensure that there was not a breakdown of the national will to resist. Experience in war is a far better guide than speculation. When Gotha bombs rained down on Folkestone in 1917, there was public alarm and questions were asked in the House of Commons, but it was not the end of civilization as we know it. The East Enders in London during the 1940 German air blitz endured the bombing with remarkable fortitude and sometimes humour, many taking to the London Underground stations during air raids, but in the heady days of 1919/20 who could tell? It was always a useful, if spurious, claim to make in justifying an air force. But one could go too far and be accused of terror bombing, an idea which Trenchard was anxious to dispel. But if the RAF was to bomb an enemy to the point where he would sue for peace it must be assumed that either he could not any longer sustain the material damage to his country, which seemed to have caused Slobodan Molosevic to call a halt to British and American bombing during the recent Kosovo conflict, or the civilian population was frightened to death. And so we see Trenchard trying to escape the accusation of advocating brutality by likening bombing to naval gunfire at a shoreline, when there might well be civilian casualties.

Douhet’s air theory The Italian General Giulio Douhet was a major air theorist of the period. His notable contribution to the development of airpower theory was his ideas about the ‘command of the air’. Douhet believed that an independent air force had two separate functions: firstly, to win command of the air, and then, having won it, to exploit it. And such an air force must be trained and equipped to achieve it. What is not clear is whether command of the air was to be achieved by air fighting or by destroying the aircraft production and allied factories. Douhet was adapting the classical Clausewitzian theory, that the object in war is to defeat the armed forces of the enemy, to the war aims of an air force. The air commanders on the Western front had aimed at air superiority, whereas Douhet’s air force would aim to secure ‘the ability to fly against the enemy while the latter had been deprived of the ability to do so’. Douhet rejected what Trenchard had felt to be necessary in the First World War, that a counter-force policy was essential. Douhet could therefore take issue with Trenchard in not making his counter-force operations decisive, i.e. to obtain command of the air; but Sykes could criticize him for devoting too much effort to those operations, preferring that he should devote more effort to strategic interception.

Air Staff Theory, 1923 In the early 1920s the Air Staff still held to a counter-force policy. Air ascendancy was imperative and meant attacking the enemy air forces both in the air and on the ground. Winning command of the air was explicitly rejected. Instead there would be a struggle for air supremacy, but there was concern that the strength of the strike force could be frittered away fighting an indecisive campaign. The enemy could replace aircraft lost during such a campaign and air space cannot be physically occupied, so it was necessary for aircraft to keep returning to attack enemy reinforcements. To prevent the enemy from reinforcing its own air units it would be necessary to attack vital centres, and this was no less risky than attacking the enemy air force. The unstated implication of the Air Staff policy in 1923 was that a counter-force policy alone would be a wasteful diversion from the main offensive. The evidence from the First World War was that a considerable amount of effort was directed against German air assets with inconclusive results. The RAF wanted to avoid an attritional war like that in the trenches, and this meant avoiding contact with the enemy. There would need to be close defence of the most vital targets, and the bombers would need some defence, but the priority for the British air effort should be to paralyse the enemy’s centres of production and lines of communication. Whereas both Trenchard and Douhet had held that command of the air was separate from the main offensive against strategic targets, the view of the Air Staff in 1923 was that the gaining of air superiority was indistinguishable from the main offensive, i.e. only by attacking the enemy’s productive capacity could the continued reinforcement of the enemy’s air forces be prevented.

What this debate amounted to was that the air theorists of the day were trying to fit the new form of warfare into pre-existing classic theories that had already been adapted to encompass a navy’s part in winning a war, and then an air force. Only an army could actually occupy an enemy’s territory, but a navy and an air force could assist in achieving final victory. On the other hand, it could be argued that a navy alone could achieve final victory through blockading an enemy’s ports, and an air force, single handed, by bombing an enemy into submission. At this juncture the ability of the RAF to achieve its war aims may be considered with the forces at its disposal.

RAF Inventory of Aircraft, 1924

The air doctrine prevailing in 1923 has been explained. The inventory of RAF fighter and bomber aircraft in the following year will show how well equipped the RAF was to carry out the roles and tasks decreed by the doctrine.

THE FIGHTERS

Snipe

Max. speed: 121 mph at 10,000 ft

Service ceiling: 19,500 ft

Snipe Mk IAs had been used as

bomber escorts with the IBF in

France and had been used as

ground attack aircraft.

Snipe (eight squadrons).

Siskin

Max. speed: 134 mph at 6,500 ft 128 mph at 15,000 ft

Service ceiling: 20,500 ft

In 1924 the Siskin was just coming into service to replace the Nighthawks and Snipes.

Siskin (one squadron).

Nighthawk (one squadron)

Max. speed: 140 mph at 6,500 ft

138 mph at 10,000 ft

Service ceiling: 24,500 ft

Problem with the engine and

vibration problems

causing mechanical failure.

Nighthawk (one squadron).

The above ten squadrons comprised the RAF’s fighter strength in mid-1924. The Snipe was of First World War vintage, and it and the Nighthawk were about to be replaced by the Siskin and Grebe. All these squadrons were based in the United Kingdom, since there was no prospect of air opposition during operations in the Middle East and India. If the fighters were employed purely in the defence of the United Kingdom the bases such as Northolt, Duxford, Hawkinge and Henlow would be adequate to cover the Home Counties and East Midlands, for they had a service ceiling that exceeded the bombers of the day and possessed the necessary endurance to permit them to intercept incoming aircraft, though not to provide close fighter support to the bomber streams leaving UK bases to bomb continental targets. The standard armament of all 1920s aircraft was the Vickers 0.303 in. forward-firing machine-gun. All of these fighters were faster than the British bombers of the day, and successful interception of potential enemy bombers could be expected. The ten squadrons of the front-line force would total some 120 aircraft.

In the foregoing discussion of doctrine, counter-force operations were considered. If enemy fighters were to be suppressed by bomber operations, that might be achieved by bombers operating from UK bases attempting to destroy enemy fighter aircraft on the ground. But airborne enemy fighters, fighting to defend continental targets, would need to be brought down by RAF fighters, which would have a very limited arc of operations from bases in South-East England or East Anglia. Counter-force operations involving the suppression of continental fighter forces would therefore mean RAF fighters operating from forward bases. If strategic RAF bombing aimed to avoid contact with the enemy, they would be unlikely to do so by having a service ceiling less than enemy fighters or the speed to outrun them, aircraft like the Fairey Fox being the exception. RAF bombers that were avoiding contact with the enemy would, none the less, expect to be intercepted as they approached their targets. In this case, without close fighter support, the RAF bombers would have to rely on trainable guns for the bombing aircraft, which would have to fly straight and level over the target area. In other words the bombers could not use fixed forward-firing guns unless, by sheer chance, an enemy fighter came into a bomber’s sights. The RAF fighters and bombers of operational squadrons in 1924 are shown, together with their ‘potential’ French enemies.

THE LIGHT BOMBERS

Fawn (three squadrons)

Range: 650 miles

Max. speed: 114 mph at sea level

Bomb load: 460 lb

Service ceiling: 13,850 ft

Fawn (three squadrons).

Conceived as an Army Cooperation aircraft, it replaced the DH9A in squadron service.

DH9A (two squadrons)

Range: 322 miles

Max. speed: 123 mph

Bomb load: 660 lb

Service ceiling: 16,750 ft

DH9A (two squadrons).

The DH9A was of First World War vintage and was being replaced by the Fawn, which had a smaller bomb load and lower service ceiling.

The home-based light-bomber force of mid-1924 comprised five squadrons. On the assumption that there would be twelve aircraft per squadron, one Fawn light-bomber squadron could deliver a maximum of 5,520 lb of bombs on a target, provided there was no fighter opposition, excellent weather, 100 per cent serviceability and detonation of all bombs. A DH9A squadron could deliver 7,920 lb of bombs at a greater speed than a Fawn squadron, with a greater service ceiling. The probability, given the inclement weather over northern Europe, the chances of being intercepted and the serviceability record of the DH9A, was that the tonnage of bombs dropped would be significantly less.

From the home stations of Spittlegate, Netheravon and Andover the Fawn’s maximum range would take them to Berlin in the east and Milan to the south, but this would be the extreme of range and would not be accomplished under severe weather conditions or the necessity to take evasive action. The two DH9A squadrons at Spittlegate and Eastchuch could just reach Paris and the low countries. To penetrate deep into Europe both squadrons would require forward bases on the continent. The speed and service ceilings of both aircraft meant that they would be unlikely to outrun enemy fighters, and could not outclimb them. If intercepted the Fawn had two trainable guns, the DH9A just one. Would these five squadrons be used against strategic or tactical targets? If the British Army was not engaged on the continent, then all sixty aircraft of the light-bomber force would have to operate from UK bases, and could be used on counter-force operations or attacks on lines of communications. Over industrial targets they would almost certainly meet defensive fighters and anti-aircraft fire.

The Fawns that replaced the DH9As on light-bomber squadrons were themselves replaced by Horsleys and Foxes after only two years’ service, and the latter would enhance the force considerably. The DH9As were more at home in India and the Middle East, where they were employed as general-purpose aircraft.

THE HEAVY-BOMBER FORCE

Range: 300 miles

Max. speed: 110 mph at sea level

Bomb load: 2,200 lb

Service ceiling: 14,500 ft

Aldershot (one squadron).

Range: 900 miles

Max. speed: 100 mph at 6,500 ft

Bomb load: 2,476 lb

Service ceiling: 14,000 ft but

with a full bomb load only

7,000 ft

Vimy (two squadrons).

Range: 985 miles

Max. speed: 98 mph at sea level

Bomb load: 3,000 lb

Service ceiling: 9,400 ft

Virginia (one squadron).

French Fighters

Max. speed: 146 mph

Service ceiling: 27,885 ft

Nieuport-Delage NI-D29.

Max. speed: 143 mph

Service ceiling: 29,530 ft

This particular aircraft is one of

a batch exported to Turkey.

Bleriot SPAD S.51-4.

French Bomber

Range: 248 miles

Max. speed: 99 mph

Bomb load: Not given

Service ceiling:13,125 ft

This civilian passenger aircraft

was produced in a bomber

version, F.60, delivered in 1922.

Farman Goliath.

According to the Air Staff doctrine of 1923, the RAF should avoid an attritional counter-force war and attempt to paralyse the enemy’s centres of production and lines of communication as a matter of priority. Only by destroying the enemy’s war-production capability could aircraft reinforcement be prevented. To achieve this in 1924 the RAF had four squadrons of heavy bombers. The planned Home Defence Force was going to comprise fifty-two squadrons, of which thirty-five would be bomber squadrons. Clearly this force of four squadrons was inadequate for the task outlined in the Air Staff Memorandum of 19 July 1923 sent by Trenchard to the Air Officers Commanding Central and Inland Areas, namely to paralyse an enemy’s production centres and lines of communication and to break an enemy’s morale. Any discussion about the RAF’s planned ability to accomplish these aims must proceed on the basis of thirty-five, and not four, squadrons. Clearly the inability to meet the war aims of the RAF in 1924 does not invalidate the doctrine, but if, given the appropriate numerical strength plus adequate reserves of the latest design, the war aims still cannot be realized, then it does call into question the doctrine itself if, in all circumstances, it would be unachievable.

The Aldershot entered service in 1924, only served on one squadron and was withdrawn after only eighteen months. It was single-engined, and if force-landed would almost certainly have had to be dismantled to effect recovery. The Virginia and Vimy were two-engined bombers. The Aldershot had two trainable guns and a range of approximately 300 miles, and the other two each had three trainable guns and a range of close on 1,000 miles. Assuming a total of twelve aircraft per squadron, the combined bomb load of an Aldershot bomber squadron would be approximately 26,400 lb, a Vimy squadron 29,000 lb and a Virginia squadron 36,000 lb. These figures are absolute maxima, and ignore adverse weather conditions, fighter and anti-aircraft defence over the target, aircraft unserviceability and aircraft not reaching the target. All three aircraft had top speeds between 92 and 110 mph. The service ceilings of the Aldershot and Vimy bombers were below 15,000 ft, and that of the Virginia, even in the most advanced Mark, was below 10,000 ft. So none of these three bombers could outrun or outclimb any French fighters of the day:indeed, the latter had a service ceiling and speed superior to the British fighters of the day.

The development of bombs and bomb aiming And so there are a number of factors that affect a bomber squadron’s ability to accomplish its tactical or strategic objective. The above figures tell us nothing about the destructive force of a given bomb load, the quality of navigation, the tactics to be employed over the target, the effects of flying in formation, the hitting power and positioning of defensive armament and the armouring of aircraft, not to mention the target area defences, such as barrage balloons and anti-aircraft guns, as well as the fighter threat. Did the Air Staff in the early 1920s address these problems or did they proceed from the premise that the bomber will always get through? Little, if anything, appears to have been done in the inter-war years either to test the destructive power of bombs or to develop them in any way. The bomb loads of various aircraft are given, both in this chapter and in Appendix A, but it tells the reader nothing about the charge to weight ratio of bombs held in RAF bomb dumps in the early 1920s, which were mostly left-overs from the First World War. This situation prevailed right up to the outbreak of the Second World War, when, as John Terraine points out, British bombs were, generally speaking, awful. Often they failed to explode, and when they did they produced negligible results. This view is confirmed by H.R. Allen, who put the figure at 20 per cent of those bombs dropped. With a charge to bomb weight ratio of 1:4, actual bomb loads begin to look less impressive, but Trenchard had stressed the morale effect of bombing, and it seems therefore not to have mattered how destructive British bombs were as long as they made a loud noise and frightened the civilians. With regard to bomb-release and bomb-aiming equipment, it is clear that again little, if anything, was done to learn from the lessons of the First World War. In the 1920s there was no dedicated member of the crew who would release the bombs, as was the case during the Second World War; indeed, one of the reasons why the Air Specifications called for bombers with minimal manning was that it reduced the problems of communication between crew members in flight. Bombs could either be dropped from high level, low level or using dive-bombing techniques. Bombing at low altitude meant that the bombers ran the gauntlet of fighters, barrage balloons and light anti-aircraft fire. Bombing from high altitude might have reduced these risks, but great accuracy could, because of wind and weather, be extremely difficult to achieve. Lack of advanced navigational equipment meant that the bombers would be likely to fly only in good weather where the target could be seen from the air and where navigation could be by reference to landmarks. There was no bombing development unit during the inter-war years, so that by the time Edgar Ludlow Hewitt took over Bomber Command in the period 1937 – 40, his Readiness Reports disclosed the Command’s inability to reach even the general vicinity of a target, let alone hit it with any degree of accuracy. One explanation for this sorry state of affairs was that the adequacy of bombs and bomb-aiming equipment was sufficient for air-control operations, but not a European war.

Aircraft design Chapter 5 deals, in considerable detail, with the wood versus metal debate that continued unabated during the 1920s. With the very limited funds available for aircraft research and development and the availability of a huge war surplus of wooden-built aircraft of First World War design, the situation facing the Air Staff militated against ordering or buying aircraft of a more advanced design. It has been told how the Air Staff kept the aircraft manufacturing firms alive with orders for prototypes, so it would be a brave firm that would ignore the Air Ministry Specifications for the different aircraft types. De Havilland and Short Brothers were less prone to design and build aircraft that slavishly followed RAF requirements, since they produced aircraft ordered by the airlines, who wanted speed with economy. The Silver Streak all-metal aircraft from Short is an example. On the other hand de Havilland produced aircraft of wooden construction that were in advance of aircraft being ordered by the Air Ministry. All-metal construction meant added expense and delay, but in 1925 the Air Staff was working on three all-metal bombers, four fighters and one Army Cooperation aircraft, though in the event the future of all-metal aircraft was sacrificed in the name of expediency. The definition of all-metal underwent a subtle change, to mean a metal airframe covered by fabric. Moreover, the bombers and fighters remained biplanes with open cockpits. Metal armour might be fitted to protect crew positions, but every pound of metal added meant a sacrifice of speed or bomb load unless there was a compensating increase in engine power.

Defensive armament In the context of offensive bomber operations, the bomber that was going to get through in spite of all things would be the one that had the speed and manoeuvrability to avoid interception and destruction. If the capabilities of French fighters of 1924 are a guide, evading interception would be problematical, which made the alternative, to sacrifice speed and bomb load by fitting more defensive armament, a better proposition. To meet the fighter threat, what was needed was not simply fixed forward-firing machine-guns and one or two trainable Lewis guns, but guns in some or all of the other positions, which included the ventral, dorsal, nose, tail and beam gun positions. The HP V/1500 went a long way towards providing the RAF with a well-defended, long-range heavy bomber, but it was not retained in the peacetime RAF. The Air Staff’s answer was the Aldershot, the first peacetime long-range bomber built to Air Ministry Specification 2/20 . This had one fixed forward-firing machine-gun and one Lewis gun in the mid-upper position, with the possibility of fitting another gun in the ventral position. A bomber is not like a fighter where the aircraft is manoeuvred into a position where the fixed forward-firing gun can be fired at an enemy aircraft, as the bomber must be kept straight and level over the target for the bombs to be aimed. And so the Aldershot crew would be hard put to fight off a fighter attack from a beam position or a head-on attack from above or below, and for the Aldershot to shake off fighters it had a maximum speed of only 110 mph at sea level and a cruising speed of 92 mph, with a service ceiling of 14,500 ft. In defence of the Air Staff’s position, these were the days before radar. When RFC and RNAS fighters sought to defend London against Gotha attacks in 1917, there was no early warning from radar stations, and the chances of intercepting the German bombers were not good. Only if continuous air patrols were maintained could the chances of interception be improved, and that would require a large number of fighter squadrons, possibly round the clock, to give adequate protection to the capital. Flights of fighter squadrons were dispersed to a number of airfields around London, but the density of cover required could only be achieved by withdrawing units from the Western Front.

The hitting power of the gun itself was also a matter that could have received Air Staff attention, but the 0.303 in. Vickers and 0.303 in. Lewis gun remained the standard armament of RAF aircraft throughout the 1920s. The 0.50 in. machine-gun had the hitting power but suffered from developmental problems. It could not sustain the rate of fire consistent with Air Staff requirements and was markedly heavier than the Vickers and Lewis guns, which meant that the maintenance of status quo was favoured. In particular the 0.50 in. machine-gun could not achieve the lethal density required, though this might have been achieved with a lower volume of fire. Experiments with cannon went little beyond the conceptual stage, and the COW gun also did not meet with Air Staff favour (see Chapter 5).

Bomber tactics on the approach to and over the target To ensure that the bomber would stand the best chance of reaching and successfully bombing the target, three possibilities could be considered and tested:

- For the bomber to have the speed and manoeuvrability to evade detection and interception.

- For the bomber formation to be provided with a long-range fighter escort.

- For bombers to fly in formation so that the guns of each aircraft would provide an interlocking network of fire.

The Air Staff could adopt the attitude that the bomber would always get through and simply rely on speed and manoeuvrability to evade detection and interception, but even without radar that was decidedly risky, and Trenchard had ruled out long-range fighters with their high development costs. The vulnerability of bombing aircraft to fire from fighter aircraft was discussed in the preceding paragraph, and so a possible answer lay in formation flying, but how big a formation and what about the problems associated with control of the bomber formation and the direction of the fire of air gunners? A smaller formation would be better if effective control by the formation leader was to be maintained at night and in bad weather with poor visibility or where manoeuvrability was important in the face of fighter opposition. A larger formation could put up a greater volume of defensive fire but would lose the advantages of the smaller formation. What methods were to be employed to ensure that the formation leader could alert aircraft captains of the approach of enemy aircraft and vice versa, and how would the latter direct the fire of individual gunners onto attacking enemy fighters both by day and by night? These questions were not being asked or put to the test in the 1920s, and it was not until 1938 that Bomber Command’s Senior Air Staff Officer, Air Vice-Marshal D.S. Evill, put such questions to the Air Fighting Development Establishment. It is therefore of interest to reflect that the US Army Air Force was developing its ‘Flying Fortress’ in the late 1930s, and the defence of the bomber formation was meant to lie in the volume of interlocking fire of aircraft in close formation. But in the event unsustainable losses to the German Fw190s could only be prevented by the provision of close fighter escort from the Lightnings, Thunderbolts and Mustangs.

1927 Air Exercises

Since no attempt had been made to provide detailed answers to the above questions, the Air Staff in 1924 could not know whether the prevailing doctrine was valid. It was not until 1927 and 1928 that national air exercises were carried out, and these were then followed in 1929 by a restatement of the doctrine. The air exercises were described in Chapter 3, and in those of 1927 a formula was used that gave fighters only a 1 in 2 chance of making a successful interception, while the bombers were arbitrarily given twice the hitting power of a fighter. The accuracy of the bombing was assessed by using a camera to record the aircraft position at the moment of bomb release, but since no live bombs were used the umpires could only guess at the amount of damage sustained in the target areas. The forces pitted against each other were those of Eastland, comprising eight day- and night-bomber squadrons of the Wessex Bombing Area and eleven squadrons of the Fighting Area defending London known as Westland. The aim of the exercise was to see if the fighters could defend all the targets being attacked, some of which were outside London. Four years had elapsed since the declaration of the Air Staff theory in 1923, and it may be seen how far aircraft design and development had come since then. These were the opposing forces:

Remarks

There is little to choose between the light bombers and the fighters in appearance. The bombers are all a little slower than the fighters with the exception of the Fairey Fox which was marginally faster than the Gamecock and over 10mph faster than the Siskin. There is no improvement in the defensive armament of the bombers since 1923 except for the Hyderabad which had nose, midship and ventral gun positions but then the top speed of the Hyderabad was less than the Aldershot and carried only half the bomb load. The light bombers bombed by day and the heavy bombers by night. Radial engines were favoured for the fighters since their external cylinder pots made for easier maintenance but their unstreamlined shape gave them only a slight advantage in speed over the light bombers.

The results of the 1928 air exercises were much the same as those of 1927. There was held to be an improvement of the fighter’s ability to intercept the bombers, but there had also been an improvement in the air pilotage of bomber crews. Clouds and strong winds were held to favour the bomber by day and the fighter by night, but since the heavy bombers were attacking by night it was these that the RAF was relying upon to break an enemy’s morale and will to fight on. If the Hyderabad is a guide, the improvement in defensive armour was at the expense of bomb load. This was also the last bomber to be made out of wood.

Conclusion

There was only a little improvement in speed and armament of heavy bombers over the decade from the HP V/1500 to the Hyderabad. There was no improvement in the firepower of aircraft guns, and little or no attempts had been made to improve the destructive power of the bombs. There was a presumption that the enemy would adopt the same strategy as Britain, known as ‘mirror imaging’, i.e. they too would concentrate resources on bombers and so reduce the fighter threat to RAF bombers. If the enemy did not the RAF’s faith in the ability of the bomber to get through was misplaced. But Trenchard was not to be moved on this central theme, and there follows a discussion of the air doctrine prevailing in 1929.

It is easy with hindsight to be critical of Trenchard and his staff in the 1920s. They did not know then that an even more destructive world war, ending with the nuclear bomb, was only a decade away. As far as they could see into the future the only operational work for the RAF was in controlling the activities of tribesmen overseas. The ‘Ten-Year Rule’, the Locarno Treaty, the Kellogg – Briand Pact, pacifist Labour governments and the pursuit of disarmament created an atmosphere of calm. The RAF’s arsenal may not have been much improved over the decade, but at least the service was ‘the best flying club’ in the world. So what was the hurry?

Air Doctrine in 1929

Following the presentation of the Air Estimates to the House of Commons in March 1929, the Air Minister, Sir Samuel Hoare, praised the achievements of the RAF at home and abroad since its formation eleven years earlier. Now that the RAF was firmly established, Admiral Sir Herbert Richmond, Commandant of the Imperial Defence College, had recommended that it was time the ‘principles of war’ should appear in the Service Manual of all three services in identical terms. Trenchard suggested that this proposal had been prompted by the Army’s and Navy’s unwillingness to accept the Air Staff view that in future wars air attacks would most certainly be carried out against the vital centres of communication and the manufacture of munitions of every sort, no matter where these centres were situated. Whatever the other two services believed were the main objectives of the RAF in war, Trenchard was determined to lay down a ‘marker’, and he clearly felt that this was a good time to state RAF doctrine explicitly. The resulting paper was titled ‘The War Object of an Air Force’, and in its essentials it was to form the basis of Air Staff strategic thinking until the Second World War.

The Defeat of an enemy nation Trenchard believed that the object of all three services was to defeat the enemy nation, not just his armies in the field or its naval forces, nor the attainment of air superiority over an enemy’s air force. The enemy nation meant its homeland, with its communications, industries, ports and cities. Having said that this should be the object of all three services, he was well aware that the RAF was uniquely placed to carry the war to the enemy homeland over the heads of Royal Naval ships and the British Army. For an army to achieve this objective, he reasoned, it must first defeat the enemy’s army, and this was a barrier to overcome before the enemy nation could be defeated. But the RAF did not need to defeat an enemy’s armed forces in order to defeat an enemy nation. To do this it would penetrate the enemy’s air defences to attack the centres of production, transportation and communication. Destruction of these centres would mean that the armies in the field and naval forces at sea would eventually be deprived of supplies of munitions, spares, replacement aircraft, ships and tanks, etc., and thus be forced to retreat or surrender. He further believed that it would not be necessary for there to be a series of air battles where one side gained air superiority before proceeding to attack the enemy homeland. While conceding that there would be air battles of some intensity and that enemy air bases would have to be attacked, such attacks would not be the main operation. Thus the gaining of air superiority would be incidental to the main direct offensive on the enemy’s homeland even if carried out simultaneously with it.

The air offensive and international law Trenchard also addressed the question of the legality of aerial bombing under international law. The problem was that if the bombing of military, industrial, transport and communications were legitimate acts of war such targets might be close to or within centres of civilian populations. Trenchard answered this by likening aerial bombardment of coastal towns by naval guns when civilians might be caught up in it. The main thing was to do everything possible to limit the destruction of civilian life and property. What he did regard as illegitimate was the indiscriminate bombing of the civilian population for the sole purpose of terrorizing the people. This may have been the doctrine that the Air Staff took into the Second World War, but things turned out very differently in the heat of battle. Of course we have the benefit of hindsight. Whether we are talking about the destruction of Coventry and the London blitz in 1940 or the sustained US/RAF bomber offensive involving the destruction of cities like Cologne, Hamburg or Dresden, such attacks hit civilian populations. Whether or not the purpose or the effect was to terrorize civilian populations is, of course, debatable. In the inter-war years there was a basic Air Staff assumption that sustained bombing would result in an enemy suing for peace. Again, whether or not that could be achieved by simply waging war against military and industrial targets is also debatable.

Finishing a war Trenchard was careful not to assert that the RAF could finish a war alone. Airpower could be used in conjunction with naval forces to blockade, and with armies in the field to defeat enemy armies This would be materially to assist in keeping up the pressure on the enemy, but he returned to his main theme, the attacks on the enemy homeland, which would bring about the destruction of the enemy’s means of resistance and the lowering of his determination to fight. He stressed the inevitability of aerial bombardment in a future war, something that, incidentally, the other service staffs did not deny. Where they differed from the Air Staff was in the claims made for the power of the Air. He then asserted that, in a vital struggle, all available weapons had been used in war and would continue to be used. He felt that there was not the slightest doubt that in the next war both sides would send their aircraft without scruples to bomb those objectives that they considered the most suitable. That was to suggest that an enemy might attack Britain by setting out to terrorize the British people. If an enemy fought ‘with its gloves off’, would Britain fight with them on or might this country be forced to do likewise? Was there a distinction between defeating an enemy nation and finishing a war? Was it not only an army that could occupy an enemy territory and disarm its forces, and was it not only the use of naval vessels that could ensure that all enemy vessels had been rounded up or sunk? Until that happened would the war be finished? These are questions that were not answered in the Memorandum.

Reactions to the Memorandum

It was inevitable that the Naval and Army Staffs would find the tone of Trenchard’s paper condescending. The RAF would be the service to deliver the lethal blow, but the other two services could play their part in keeping up the pressure on the enemy. Predictably , Sir George Milne, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, opposed Trenchard’s Memorandum when it was circulated to the Chiefs of Staff Committee. He objected on three grounds. Firstly, he felt that the RAF was proposing that it could fight a war independently of the Royal Navy and the Army. Secondly, he felt that the paper amounted to a declaration of ‘unrestricted warfare’ against the civil population of an enemy nation. And thirdly, the General Staff believed that the most probable conflict involving the British Empire would be against Russia in Central Asia. Milne conceded that Trenchard’s air offensive might work against France, the least likely of enemies, but he could not see the RAF paralysing production centres in such a vast continent as Asia. And in a war against Japan carrier-borne air forces would be needed to attempt to achieve the Chief of the Air Staff’s war object. Of course, heavy bombers could not take off from aircraft-carriers, and in 1929 it would have been difficult to imagine light bombers like the DH9A, the Fox and the Fawn, used in the 1927/28 air exercises, flying long distances over enemy territory with a pilot, a gunner and bombs slung beneath the wings. Another problem for Trenchard was the paucity of war experience upon which to base a doctrine. Nothing that happened in the First World War pointed to the certainty that Britain could paralyse an enemy through the use of airpower alone. The Independent Bombing Force came into existence only in the last year of the war. For the most part airpower had been used to support naval forces at sea and the armies in the field. The Zeppelin and the Gotha raids on Britain did involve civilian populations in war in a way never experienced before, but neither the life of London nor Britain’s production centres were paralysed. And when the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and Turkey) did seek an armistice in late 1918, their economies were not in a state of near-collapse. Even supposing the war had continued into 1919 with aircraft like the HP V/1500 four-engined bombers attacking Berlin, evidence of sustained attacks on enemy targets showed that such attacks only hardened the will and strengthened the resolve to resist. Be that as it may, it was believable that sustained aerial bombardment would be a frightening prospect in the public’s imagination. Who could tell for sure? In the event, Sir Maurice Hankey, the Secretary to the Chiefs of Staff Committee, considered that Trenchard tended to exaggerate ‘both the actual power of the air and its morale effect’, and he advised the CAS to recast his memorandum to recognize that the aerial offensive, although important in winning a war, was by no means the sole means. Indeed, Hankey brought to bear all his experience of the First World War in government meetings, in conversations with other authorities on air matters and in his own observations on the front line. The full texts of his letters to Trenchard and Trenchard’s reply are to be found in Appendix Q. He went so far as to give his opinion that Trenchard’s claims for the power of the Air were an ‘abuse’ of language. Hankey’s criticisms were so hard hitting that he had to ask the Air Marshal not to be cross, and to accept that the war object of the RAF was to contribute, with the Army and Navy, towards the breaking down of the enemy’s means of resistance. And there for the time being the matter rested. The Chiefs of Staff failed to agree on a common definition of the war object of the three services for inclusion in a joint service manual.

Conclusion

The controversial nature of Trenchard’s paper meant that it was hardly likely to meet with the approval of the other two services. He was on the point of retirement as CAS and he was understandably proud of what had been achieved under his stewardship in just ten short years. Given the sustained attack on his service by Admiral Beatty and General Wilson in the immediate post-war years, Trenchard may be forgiven for coming up with a ‘big idea’ that portrayed the RAF as the prominent service, with the Royal Navy and Army playing a supporting role. Some might say that his paper was impudent, and it is not surprising that it did not gain acceptance. When the war did come in 1939, the RAF did put light-bomber forces into the field, but in support of the land war, and in that it failed. It is one of those rich ironies that the RAF’s first major battle since the statement of air doctrine in 1929 was a defensive fight for survival in the skies over Kent and the Home Counties in the late summer of 1940.

THE ORGANIZATION AND BUSINESS OF THE AIR MINISTRY

Organization of the Air Ministry from 1921 to 1929

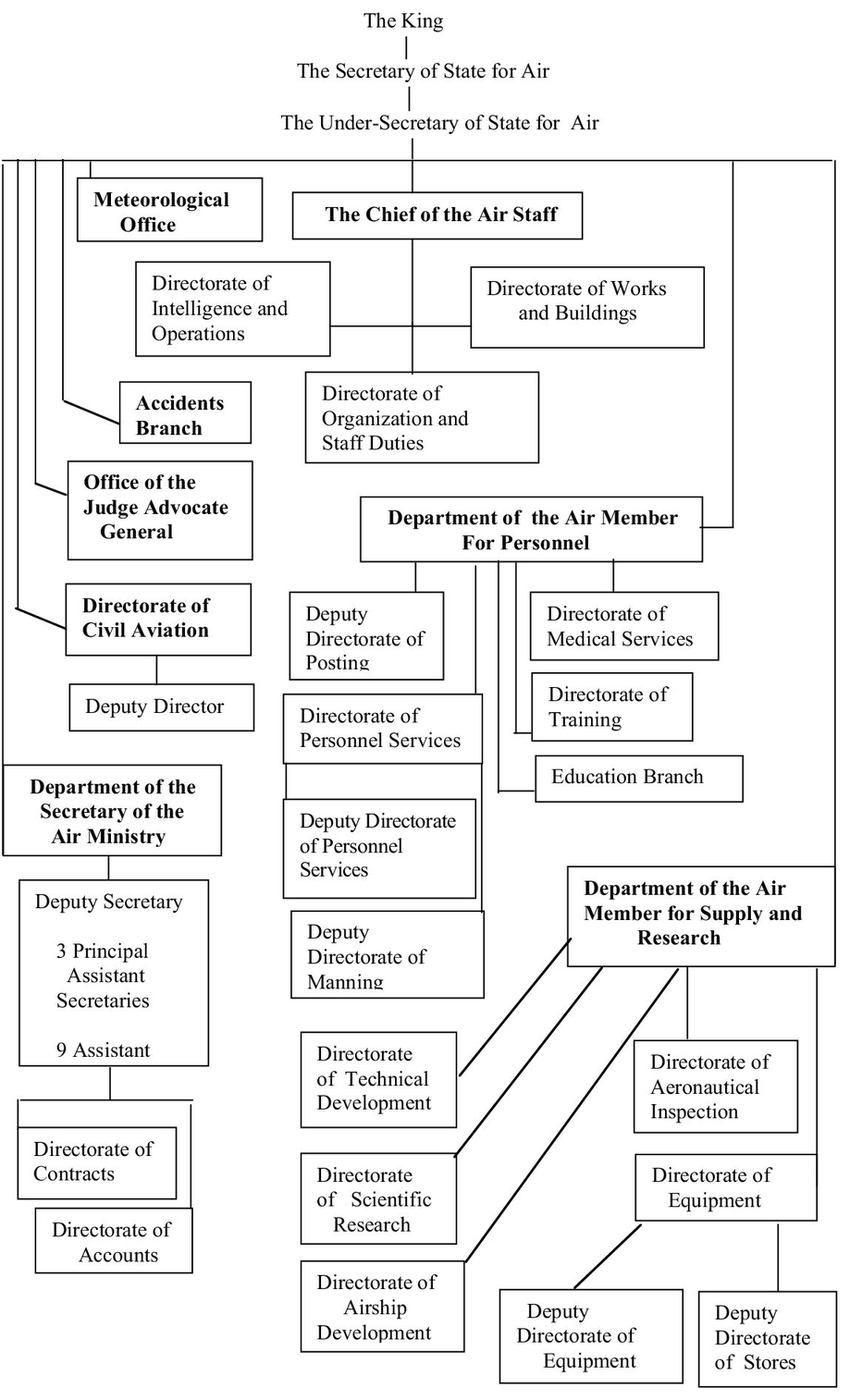

The organization of the Air Ministry at the beginning and the end of the decade that is the subject of this volume may be found on the next two pages. This shows the considerable changes that had taken place in the Air Ministry’s internal departmental structure. One example is the appearance of an Accidents Branch following the spate of accidents in the 1920s that gave rise to questions in the House of Commons. It shows a considerable narrowing of the sub-departments that came directly under the Chief of the Air Staff. Equipment, personnel, training and medical services all moved out to other departments. Throughout the period civil aviation came directly under the Secretary of State for Air. Works and buildings remained directly under Trenchard, an indication of his determination to build up the RAF’s real estate in these formative years. The RAF Cadet College at Cranwell is a particular case in point.

The Air Ministry in 1919

During the last few months of the First World War the RAF was administering a force of some 188 squadrons, 30,000 officers and 300,000 men. The HQ was in the Hotel Cecil in the Strand, and branches spread into several buildings in Kingsway. The Kingsway branches mostly housed those staff officers dealing with the delivery of contracts and supplies of raw materials to the contractors who were building aircraft and aero-engines.

Organization of the Air Ministry, 1921

Their work also covered scientific research. Once hostilities ceased many of these offices on the west side of Kingsway and the Hotel Cecil were deserted, and the staff officers, known as the ‘Kingsway Captains’, got back into their plain clothes and returned to civilian life. It was at this point that the Air Staff sought a new home, and obtained premises on the east side of the south end of Kingsway. This became known as Air House, and was conveniently near to the War Office and the Admiralty.

Reference to the charts on pages 310 & 311 will show that the King headed the RAF, but since every RAF officer carried his commission this was unsurprising. Under him was the Air Council, headed by its political master, the Secretary of State for Air, and as a general rule, each member of the Air Council headed one of the departments into which the Air Ministry was divided. The Department of the Chief of the Air Staff was run by the RAF’s most senior officer, Hugh Trenchard, who had a seat on the Council.

The Air Ministry in the 1920s

The Secretariat Much of the Ministry was run by civil servants who represented the Treasury when it came to spending money. It was the Secretariat of the Air Ministry that approved the price at which supplies were bought and refused payment if the goods were not up to specification. The first civil servant to head this department was Mr W.A. Robinson, followed by Mr W.F. Nicholson, who was appointed in April 1920 and remained for the rest of the decade. In these early days there were one or two interesting departments. One was earmarked for legal work, another was engaged in writing the Air History of the War for the Committee of Imperial Defence. Yet another was Secretary to the Commission of Awards to Inventors. Then there were the statisticians and accountants with a Directorate of Accounts and of Contracts. There were constant disputes with suppliers of all sorts in respect of raw materials, component parts, accessories, complete aircraft and engines, etc.

The Directorate of Lands The Directorate of Lands, known affectionately as ‘Bricks and Buildings’, had the responsibility to buy or commandeer land for aerodromes and to demolish old buildings. In those early days, however, the directorate was more concerned with selling off unwanted land or auctioning buildings and contents. Reference to the organization diagram for 1930 shows that the directorate is absent. By that time the airfield situation at home had stabilized, and the unwanted airfields, seaplane bases and landing grounds had all been disposed of.

The Department of the Chief of the Air Staff This was the purely service department of the Air Ministry, which actually made war. The Chief of the Air Staff was in effect the Commander-in-Chief, and had overall operational control of the service, although the Cabinet and the Committee of Imperial Defence might have some input into operational decisions. The Directorate of Operations and Intelligence dealt with plans for all operations being undertaken and for intelligence. This would include collecting, collating, filing and tabulating all sorts of apparently innocent bits of information. Pictures out of foreign newspapers, photographs of foreign celebrities and articles from newspapers could give away valuable information. An article written in all innocence could contain, quite unknown to the writer, information that could be of use to an enemy or potential enemy. Under this department came the Liaison Officers who worked with the British Dominions, and the Air Attachés who were accredited to foreign governments and were attached to British Embassies and Legations. Then there was Training and Organization. At the beginning of the decade personnel matters came under this directorate, but there was later a department devoted to personnel matters. Another directorate which came under the CAS in the early days was that for equipment, which covered the design of aircraft and aero-engines and the materials from which they were constructed.

Organization of the Air Ministry, 1930

The reason for placing the Director of Medical Services under the CAS in the early 1920s was that, apart from the need to have doctors treating war casualties in the field, they were also responsible for seeing that officers and men were fit to go to war if need be. That sub-department, too, was moved, later, to the Personnel Department. Works and Buildings came firmly under Trenchard’s control, as has been explained, and the work involved the location of airfields and the design and construction of buildings in which men were housed. These all directly affected the readiness of the RAF to go to war.

The Controller-General of Civil Aviation One of the first things that the Air Ministry did after the First World War was to impose a system of supervision over all civil aircraft and their pilots. Before anyone was allowed to fly outside an airfield at which he was a pupil, he had to qualify for an Aviator’s Certificate. There were two classes of certificate for civil aviators – one the ‘A’ licence for a private pilot, and the other the ‘B’ licence for the commercial pilot. Those who had applied for both ‘A’ and ‘B’ licences had to submit to a medical examination by the same panel of doctors who examined RAF pilots. As it happened, the medical for the Class ‘A’ pilots was not as strict as that for RAF pilots, the doctors mainly wishing to ensure that the applicants would not faint in the air and had good eyesight. Before an aircraft was allowed to fly outside the airfield at which it was put together for flying, a Certificate of Airworthiness had to be obtained from the Department of Civil Aviation. The officials were members of the department of Supply and Research who examined the civil machines, and they had to consider whether the designs of aircraft were such that they could stand the stresses of flying. These calculations were based on the known strength of the materials used for both civil and military aircraft.

A Controller of Communications worked on developing systems of signalling, radio-telephony and wireless telegraphy. This benefited military as well as civil aviation, and the Controller was served by two senior assistants, six junior assistants and four officers attached from the RAF, together with two officers detached from the map section of the War Office.

A further sub-department was that dealing with aerodromes and licences. Anyone who owned land who wanted to turn it into a public aerodrome had to get the approval of the Air Ministry. The two main criteria of fitness were, firstly, that the surface of the airfield was such that it would not break any normal aircraft on landing, and secondly, that the approaches to the airfield in all directions, particularly that of the prevailing wind, were such that a pilot of average ability could get down safely.

Finally there was the Meteorological Office (Met. Office for short), headed by a Director and served by three assistant directors and ten superintendents. The Met. Office was formed out of the Royal Meteorological Society, which itself was a complicated organization. Although placed under the Air Ministry, the Met. Office dealt with a vast number of other industries and organizations. Its forecasts were used, among others, by the Army, Navy and agriculture. It used to be said that before issuing a forecast the Met. Office would ring up sundry farmers and fishermen for their opinion. This may be a ‘tall’ story, but it reminds us that forecasting was not the more exact science it is today. Weather maps that might have become commonplace were not published during the Second World War in case they might be of use to the enemy. The table below serves as an illustration of the scope of Met. Office responsibilities of the various assistant directors and superintendents:

Observatories

Contributive Stations (with rain gauges and wind-measuring equipment)

Forecasts

Information to and from ships

Met. Research at Benson

The British Rainfall Organization

Supply and Research

Supply meant seeing that active service members of the RAF got the aircraft, aero-engines, spark plugs, bombs and cartridges they required in the quantities they required. Research meant that that equipment was of the highest quality given the latest state of technology. The first director-general of Supply and Research was Air Vice-Marshal Sir Edward Ellington, who worked alongside Trenchard in the early formative years. Sub-departments dealt with aircraft, aero-engines, airship research, armament and instruments. The latter were in their infancy, for a pilot of the day would have just an altimeter to give him his height, an engine revolution counter, a compass and possibly an airspeed indicator.

The Air Force List for October 1921 showed that the Directorate of Research was manned almost entirely by serving officers with experience of the First World War who appreciated what needed to be done. On the other hand the Directorate of Aircraft Supplies was manned almost entirely by civilians. This may be explained by the need for heads of sub-departments to have experience in their dealings with people in the aircraft industry on the purely commercial and production side.

Aeronautical Inspection This directorate was founded by Captain J.D.B. Fulton RA, one of the first Army officers to fly before the First World War. He was succeeded by General Bagnall-Wilde, who steadily improved the department’s relationship with the aircraft industry, as did his successor, Colonel H.W.S. Outram. Not only aircraft and aero-engines had to be inspected, but so did every component part, including washers, nuts and bolts. Woods and metal being used for aircraft construction had also to be inspected. When the war ended many inspectors were demobilized, and the main problem was to retain sufficient numbers of inspectors of the right quality. As the reputation of the department increased, the aircraft industry could shelter behind the AID, knowing that if their products had got past the hands of the inspectors it must be of a good quality. Eventually the AID instituted a scheme of ‘approved firms’ that would take direct responsibility for the quality of their products, subject, of course, to periodic check inspections by the local AID inspectors.

Air Ministry Committees

The following committees give an indication of the wide scope of responsibilities of the Air Ministry:

The Aerodromes Committee considered the suitability of aerodromes for their jobs and for commandeering the land for new aerodromes.

The Advisory Committee on Civil Aviation had as its chairman Lord Weir, the former Air Minister. During the early 1920s civil aviation was going through a bad time. Mr George Holt-Thomas’s Aircraft Travel and Transport Ltd had collapsed, and other airlines were struggling, but although a number of airlines did go out of business the network of airlines was spreading all over the world at the outbreak of the Second World War.

The Awards to Inventors and Patentees Committee was kept busy recommending awards for things that were invented during the First World War and afterwards.

The Committee on the Future of Experimental Establishments was a purely domestic affair of the Air Ministry studying the problems of the Department of Research in conjunction with financial problems.

The Contract Coordinating Committee was a matter between the finance people at the Treasury, the Air Ministry and the aircraft industry. It brought in representatives of the Admiralty and the War Office to see that firms that were supplying all three fighting services were even-handed in their dealings with each.

The Committee on Cross-Channel Services (Subsidies) dealt with the problems facing four separate airlines trying to ‘scratch’ a living running services to the continent.

The Royal Air Force Committee responded to the hazards facing the operators of aircraft that owned highly inflammable aircraft and gasoline. The committee brought in people from the Ministry of Transport, electrical engineers, personnel from Works and Buildings, the Metropolitan Police and others.

The Medical Advisory Board coordinated the work of the RAF Medical Service with that of the other services and also civil practice.

The Meteorological Committee brought in people from the War Office and the Colonial Office, the Board of Trade and the Royal Society, the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, the Scottish Office and the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

The Permanent Buildings Committee was particularly concerned with giving RAF personnel decent accommodation after living in wooden huts that were built in a hurry during the First World War.

The Whitley Council was set up in all government departments and in all industries to try to bring about better industrial relations. Its work covered men in the services, including the lower grades of civil servants.

The Industrial Whitley Council dealt with manual labourers, and not office workers.

Other Committees The Air Ministry also had representatives on a lot of inter-departmental committees, such as the Imperial Education Committee; the NAAFI; the Air Survey Committee; the Standing Committee of Representatives of the Government of Ex-Service Organizations; the Ordnance Committee, which dealt with armament, much of which was common to all three services; the Radio Research Board; the Advisory Council to the Committee for Scientific and Industrial Research; the Shell-shock committee, which dealt with cases of fighting men suffering this in battle; the United Services Trust; and the Wireless Telegraphy Board.

THE AIR COMMANDERS

Appendix R lists the names of members of the Air Council and commanders of RAF formations during the 1920s.

The paragraphs that follow will firstly provide a thumbnail sketch of those officers who held the highest command positions in the postwar years, followed by a representative sample of some officers in lower positions. Many very senior officers who commanded RAF brigades, wings and areas in a service of 188 squadrons during the First World War could not survive the peace with only a skeleton organization at home and a few squadrons overseas. Those few senior officers who survived filled the few command and staff posts in the early 1920s. The opening paragraphs of Chapter 9 briefly considered the careers of four of the most senior RAF commanders, and this chapter looks closely at the contribution they and subordinate commanders made to RAF operations, organization and administration.

Hugh Trenchard

Hugh Trenchard was born in Taunton in 1873 and was commissioned into the Royal Scots Fusiliers at the age of 20. He served in India before being sent to South Africa to fight in the Boer War. By this time he was an acknowledged good horseman at both polo and racing. When he was shot through the lung he went to convalesce in Switzerland, where he won the freshman’s and beginner’s Cresta Run, and largely cured his paralysis in the process. On his return to South Africa his skill as a horseman was put to the test when Lord Kitchener sent him to organize three mounted infantry battalions, and also to organize an expedition to capture the Boer Government, though Trenchard was unsuccessful in this.

When he returned to England in 1912 Trenchard was a 39-year-old major, with only one good lung and therefore limited career prospects. The newly formed RFC did provide an opportunity to advance himself, and he learned to fly in just thirteen days, whereupon he was sent to the Central Flying School at Upavon. Though an indifferent flyer, he had military experience and was soon made deputy to the first Commandant, Captain Godfrey Paine. From there he went to command the Military Wing at Farnborough on the outbreak of war in 1914, and in November of that year he was posted to France to command No. 1 Wing RFC. It took just nine months for him to succeed General Henderson as GOC Royal Flying Corps, with responsibility for all British air operations on the Western Front. These were difficult times owing to the success of the German Fokker aircraft, and their effectiveness against British aircraft became known during this period as the ‘Fokker scourge’. In spite of this Trenchard refused to let his pilots wear parachutes. Some might regard this as a rather callous stance, while others would suggest that it showed his determination that his pilots should at all times be more concerned with pressing home their attacks.

The Air Ministry that would oversee the new RAF was set up in December 1917, and having led the RFC in France with distinction, he was the obvious choice to become Chief of the Air Staff, and he accepted this post on 18 January 1918, only to resign in March over differences of policy with the Air Minister, Lord Rothermere. He was succeeded by Major-General Sykes. Trenchard was then prevailed upon to accept a post in France in command of the Independent Bombing Force. This was his opportunity to demonstrate the strategic employment of airpower, and targets in Germany, west of the Rhine, were attacked, but the war ended before Berlin could be bombed. Since there was no need for a strategic air force of the size of the 8th Brigade, with its five squadrons of 83rd Wing, equipped with HP 0/400 bombers, and with HP V/1500s coming on line, Trenchard was again without a job. But there had been a change at the top, and the new Minister for War and the Air was Winston Churchill, who was persuaded by Lord Weir that Trenchard was the man who would best lead the RAF during a period of economic stringency. So it was that Sykes was moved to civil aviation. In the event Weir was proved right, and Trenchard remained as Chief of the Air Staff until his retirement in 1929.

Frederick Sykes

Frederick Sykes was born in 1877, and on the outbreak of the Boer War, enlisted as a trooper. He was later commissioned into Lord Roberts’s Bodyguard and was seriously wounded, but on his recovery he was granted a regular commission in the 15th Hussars. Apart from a brief spell in West Africa, he served mainly in India, where he attended the staff college at Quetta in 1908. His interest in aviation began as early as 1904, when he attended a course with the balloon section of the Royal Engineers. A soon as he could he undertook a flying course at Brooklands, where he went solo and gained his licence on a Bristol Boxkite in 1911. By that time he was a staff officer in the War Office and had become a firm believer in the importance of aerial reconnaissance in war. He was therefore the natural choice to join the Sub-Committee of the Committee of Imperial Defence to consider the way forward in military aviation. In 1912 that committee recommended the formation of the Royal Flying Corps, and he was selected to recruit, train and command the Military Wing at Farnborough. Sykes later wrote that this was the happiest and busiest period of his life. There was an added urgency to his work as war loomed larger. Treading entirely new ground, he had to acquire aircraft, construct a programme of flying training, find men to instruct trainee pilots and other men who had the technical skill to service and repair aircraft, test aircraft and carry our military manoeuvres with aircraft. This would be a daunting task for any man.