Chapter 11

The Royal Air Force and Government

Governments of the 1920s – Air Estimates, 1919 – The Liberal government – The first Labour government – The Conservative

governments of the mid to late 1920s

This final chapter describes the relationship between the various governments of the 1920s and the RAF. Of course most interaction was between the politicians and members of the Air Council. Chapters 1 to 3 showed that the attitude of members of the Cabinet towards the fledgling RAF was mixed. It was to be expected that successive War Ministers and First Lords of the Admiralty would adopt a hostile and negative stance, but Trenchard did have his friends and supporters. Airpower offered politicians a new way of waging war, and one that would certainly avoid a repetition of years of static trench warfare. Aeronautics was still in its infancy, and one could not help but be attracted by the excitement of flying. A few politicians took an active interest in flying and some were themselves pilots. Typical of the new breed of politician/air enthusiast was Major-General Seely, the Parliamentary Under-Secretary for Air in 1919, who on one occasion alighted on the River Thames in a seaplane by the House of Commons Terrace, having flown under Tower Bridge, and was rebuked by the Lord Mayor.

Be that as it may, whether hostile or supportive, Trenchard and his brother officers knew that in the immediate post-war years funds would be tight. The Air Estimates represent the Air Force’s needs for public funds for a financial year and must be approved by Parliament. Those for the financial year 1919/20 are shown at Appendix S, the year when the strength of the RAF would fall from 150,000 to 35,000, excluding the RAF in India, which was funded by the Government of India. These should be consulted because they show the various heads of vote to which the moneys were allocated, e.g. Pay, Technical and Warlike Stores, Land and Buildings, etc. From a total of £54 million in that year the sum would drop to around £15 million in succeeding years.

The 1920s are an interesting time politically because these years witnessed the first-ever Labour government of 1923, the Geddes Axe of that period, the General Strike of 1926, the Locarno Treaty and the Kellogg – Briand Pact. No one could be sure how the new Labour government would react to demands for defence expenditure. In the ranks of the Labour party there were pacifists deeply committed to disarmament who could be expected to wish to cut the armed forces to the bone. In the event it was to be economic circumstances and not deeply held political beliefs that were to result in government calls for cut-backs in defence expenditure, and the RAF had to accept its share.

The Air Estimates

The RAF’s share of the overall defence budget is shown in the following table for the 1920s, and it seems that the new service was the poor relation. The sum for the RAF for 1922 would not buy one Tornado in today’s money, which is a sobering thought, even allowing for inflation over the years.

The presentation to Parliament of the Annual Air Estimates was the occasion for the successive Air Ministers to justify the sums required and to give Parliament an update on air matters. Then the members of the Houses of Commons and the Lords would be called upon to vote the sums required. The overall sum was broken down under the following heads:

Effective Services

- Pay, etc. of the RAF

- Quartering, stores (except technical; supplies animals and transport)

- Technical and warlike stores

- Works, buildings and lands

- Air Ministry

- Miscellaneous effective services

Non-effective Services

- 7. Half pay, pensions and other non-effective services

The air estimates will be referred to again as they crop up in the discussion of the 1920s. As a matter of interest, the various governments under which succeeding Air Ministries had to work are shown on the facing page. The Chief of the Air Staff throughout the entire period was Hugh Trenchard. Within each Cabinet there was the man holding the purse strings, namely the Chancellor of the Exchequer, as well as the Prime Minster and Cabinet, who had to be convinced of the need for spending money. The official policy expressed by the Cabinet on 15 August 1919 was one of economy and disarmament, and that, in forming their estimates for the year, the three services were to assume that the British Empire would not be engaged in any great war in the following ten years and that no expeditionary force was required for that purpose. Thus the famous ‘Ten-Year Rule’ came into existence, and the period of ten years, originally intended to take Britain up to the year 1930, was extended several times until 1928, when the then Chancellor of the Exchequer, Winston Churchill, suggested that each year the Estimates for the Fighting

Services be framed annually on the basis that from any given date the period was ten years unless the Committee of Imperial Defence felt otherwise. This would simplify matters for the three service ministries in making their plans for equipment, manning, training and deployments. It would not, however, prevent the three service chiefs from attempting to increase the overall budget or their share of it. This book has already described the bitter battles between the Navy and the Army on the one hand and the RAF on the other. The reader has also been appraised of the employment of air control in Britain’s overseas territories as an economical way of keeping the peace.

GOVERNMENTS AND SECRETARIES OF STATE IN THE 1920S

1919 – 21

The Chancellor of the Exchequer in Lloyd George’s post-war coalition was Austen Chamberlain. He wrote to Winston Churchill, at that time Minister for War and the Air, on 2 September 1919 to say that things seemed to be moving in a vicious circle, since Trenchard was asking what money he could spend and the government was asking what air forces were felt to be needed in the post-war situation. Trenchard, as we have seen, was determined to create a real air service, and not one of airborne chauffeurs, which is what the Army wanted. Three schemes were put forward, but the one finally adopted was described in detail in Chapter 2, namely the Trenchard Memorandum. This was to be the blueprint for the development of the RAF in the 1920s.

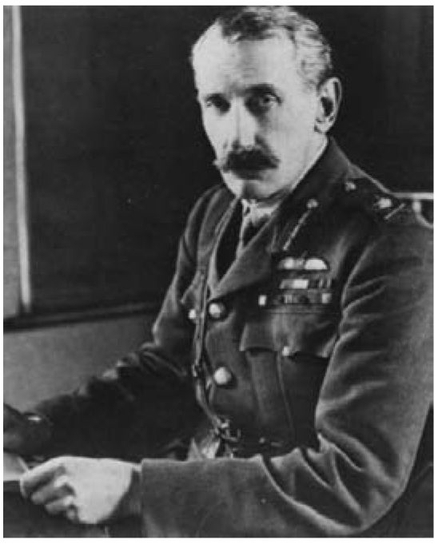

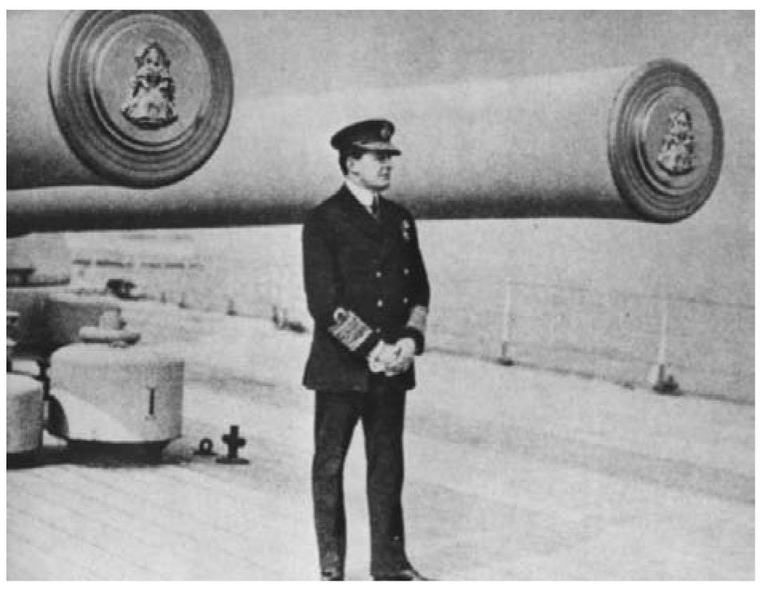

Major-General Seely as US of S for Air

Major-General Seeley was appointed to the post of Under-Secretary of State for Air in January 1919, and it was the Prime Minister’s intention that Seely should preside over the Air Council, but according to Statute this could only be done by the Minister for War and the Air, Winston Churchill. Seely found that his position was untenable, since he was supposed to be in charge of the Air Department of the War Office but felt that he wasn’t. What was needed was a separate Ministry with its own Air Minister, and it seemed strange that Churchill, who had done so much to create an independent air force, should not push hard for a separate Air Ministry. This may be understood if it is true that Winston was grooming himself to be the new Minister of Defence and head of a unified government department. Seely therefore tried to resolve matters through an intermediary, namely the newspaper proprietor, Lord Riddell, who was a close friend of Lloyd George. Lord Riddell let the PM know that Seely found his position impossible and wished to resign. But Lloyd George had no intention of creating a new government department at this time, for this would have added unacceptably to public expenditure. Thereupon Seely promptly resigned, much to Trenchard’s regret, never to hold political office again, although he did continue to support the RAF from the back benches as a Liberal MP until his defeat in the 1924 General Election.

Major-General J.E.B. Seely MP, Under-Secretary of State for Air from 10 January to 22 December 1919.

Lord Londonderry as US of S for Air

Churchill wanted Seely to be replaced by Lord Londonderry as the new Under-Secretary of State for Air, for he had been answering questions on air matters in the House of Lords and was the finance member of the Air Council. But there was opposition to his appointment from within the Conservative party, and he was passed over for Major G.L. Tryon, who only remained in post for a few months before being moved to another department in a government reshuffle. By this time opposition to Londonderry’s appointment had subsided, and he took up the post on 3 April 1920. He was soon actively engaged on air matters, and on 11 May 1920 he introduced the Air Navigation Bill into Parliament, which would form the basis of an international law of the air. Londonderry did his best to promote Britain’s leadership in the air, and he appreciated the potential of airpower, but it was mostly in a social capacity that he was an asset to Trenchard.

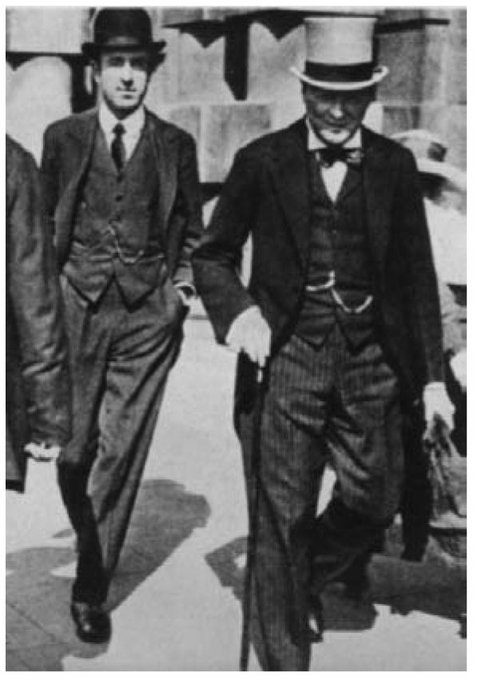

Lord Londonderry (left) with Winston Churchill.

Some members of the Board of the Admiralty, the War Office and others looked down their noses at the new Air Ministry, but Churchill did not. Socially the Ministry needed a big name, and it seems that they had found one in the new Under-Secretary of State, who was an aristocrat and a landowner, and had a wife who was a prominent hostess in London. Trenchard understood the importance of making contacts and influencing the right people on the golf course or at social functions. Lord Londonderry could fulfil that role, and the men became good friends.

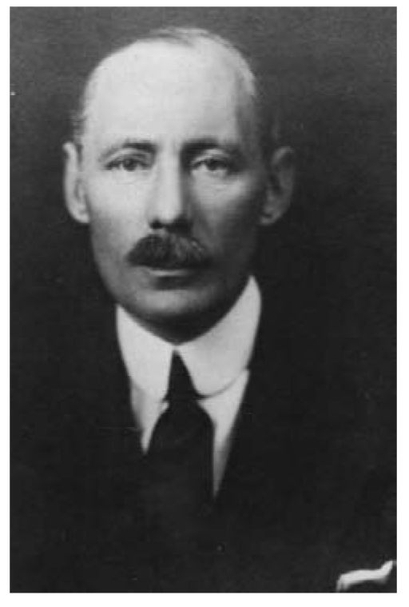

Major-General Sykes as Controller-General of Civil Aviation

In 1919 there was no separate government department to cover civil aviation, and Major-General Sykes was appointed Controller-General of Civil Aviation, thus relieving Trenchard of responsibility for civil air matters. Indeed, there was no reference to them in his 1919 Memorandum. The Air Ministry, however, was the umbrella under which Sykes operated his department. This was responsible for planning, communications, meteorological services, licences, inspections and information. From February 1919 the Air Ministry would be responsible for the issuing of public weather forecasts, and for many years to come references would be made to the temperature, humidity and wind speed on the Air Ministry roof. These services had to be provided from very limited financial resources, and it seemed unfair that Sykes should have to provide a service that served the whole country. He had much greater need for money for research into blind flying, landing at night and flying-boats that would be needed for the Imperial air routes, but three-quarters of the £2 million allocated to research went to military flying, i.e. he had to manage on £500,000 a year. The government’s view was that if extra money was wanted for civil aviation then Parliament should have to vote for it. But this raised the question that was to crop up time and again during these formative years. The very essence of commercial flying was that it was supposed to be run by private enterprise and subject to market forces. To provide public moneys might be regarded as the granting of a subsidy to firms in competition, although this never seemed to worry the French, who at that time were Britain’s most serious competitors on the cross-Channel routes. What Sykes needed was something spectacular to boost civil aviation. Crossing the Channel could be lucrative, but ever the Imperialist, Sykes was thinking of the routes to Egypt and the Far East and to Canada and the USA. The Vimy flights by Alcock and Brown from Newfoundland to Britain, and Ross Smith’s from Hounslow to Port Darwin, provided much-needed publicity to show what was possible in the future. What Sykes may have lacked in government support was in part compensated for by the leading newspapers, notable the Daily Mail, which would sponsor major aeronautical events. Sykes had been very positive in his first departmental progress report of 1 November 1919, and the Weir Committee had looked at ways of developing British civil aviation (see Chapter 2), but in the context of government – RAF relations it is evident that Sykes had been given a post that did not make sufficient demands upon his organizing ability and experience. His more grandiose plans for an Imperial air force were not what the government was looking for at a time of financial stringency, and Trenchard was, in this respect, the much safer bet. Having been Chief of the Air Staff and the leading service member of the Air Council, as Controller-General of Civil Aviation he did not warrant a seat on the Council, in spite of his impressive title, and so it could be seen as a demotion. This, together with the paucity of funding, had clearly reduced the status of his department, and Sykes resigned on 1 April 1922.

Major-General Sykes.

1921 Air Estimates

Churchill introduced the Air Estimates for the financial year 1921/2 to the House of Commons on 1 March 1921. Only £800.000 had been appropriated for civil aviation from a total of £18,410,000, and it was this that led to Sykes’s resignation a year later. The Times was particularly critical, alleging the neglect of civil aviation by the government. Lloyd George’s response was to separate War and Air into two separate departments, presumably on the grounds that an Air Minister could devote more time to both civil and military aviation without the distraction of Army matters. In the government reshuffle that followed, Churchill was moved to the Colonial Office. As it happened, Churchill was thus able to keep very close links with the RAF and give the service a real peacetime raison d’être, for it was at the Cairo Conference of 1922 that, with Churchill’s backing, air control was accepted as a new way of maintaining internal security in the outposts of Empire.

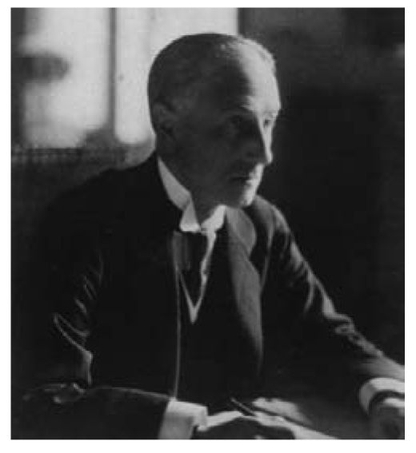

The new Ministers for War and the Air

The Conservative, Sir Laming Worthington-Evans, became the new Minister for War, and the Liberal, Captain the Hon. F.E. (Freddie) Guest, became the new Air Minister, but without a seat in the Cabinet. For the coming battles with the Navy and the Army the RAF would not be able to defend itself in the Cabinet, but on a more positive note Guest was very popular at Westminster. He was an active sportsman, a big-game hunter, and he held a pilot’s licence. He had been a Liberal MP since 1911 and had been made Patronage Secretary to the Treasury. Both he and his brother, Lord Wimborne, were related to Winston Churchill. When Captain Guest took part in the debates on the 1921 Estimates it was remarked that he knew very little about aviation but that, to his credit, he did not pretend to know. He had stated that the First World War had advanced the science of aviation one hundred years, which was a cheerful and positive note upon which to start his term of office as Air Minister. The Times of 5 April took a contrary view: ‘Military ideas had been supreme at the Air Ministry during Churchill’s time in office, including such things as the introduction of high-sounding titles and the building of elaborate aerodromes, whereas the science of flying had been neglected, there had been little progress made in the design of engines and civil aviation had been left in the cold.’ Be that as it may, Trenchard would be able to report to a minister whose undivided attention would be on Air matters, so vital in his battles with the War Office and the Admiralty. Not that Churchill, as Minister for War and the Air, had done a bad job. On the contrary, it was he who had supported Trenchard when the latter submitted his 1919 Memorandum, which laid the foundations for the permanent organization of the peacetime air force, and he insisted on the new rank titles, which emphasized the separate identity of the RAF. Even when he went to the Colonial Office he was in an excellent position to help the RAF establish air control in Iraq in 1922.

Captain the Hon. F.E. Guest DSO, CBE.

Awareness of the importance of airpower

If the RAF was to remain an independent service it was essential for succeeding governments to be persuaded of the RAF’s case. The Lord President of the Council, Mr Balfour, had submitted his report on the threefold relationship between the RAF and its sister services. Balfour’s committee had appreciated the importance of not relegating the RAF to an inferior position, and there was a recommendation that during the conduct of air-defence operations the Navy and the Army should play a secondary role. The Smuts Report of 1917 had pointed to the vital necessity of coordinating single-service attempts to defend the capital against bombardment at a time when the first priority of the Admiralty was protection of the fleet in home waters. On the other hand, the committee recommended that during the conduct of military operations on land or naval operations at sea the RAF should play a subordinate role. Where military operations were not clearly in any one sphere it was concluded that relations between the services should be a matter of cooperation rather than strict subordination. Unfortunately the other two service chiefs did not see things in that light, and did not therefore regard the findings of the Balfour Committee as the last word on the matter. Sir Henry Wilson, Chief of the Imperial General Staff, questioned Balfour’s judgement, and to his oft repeated calls for the RAF’s abolition he added a demand for an investigation into the RAF’s finances. Initially Trenchard was taken aback, but then said that he would accept such an investigation provided it was also applied to the other two services. As it happens, the government had just set up a committee to do precisely that.

The Geddes Committee

In May 1921 the Treasury had sent a circular to all government departments to the effect that there must be heavy cuts in expenditure. This would affect not only the armed forces but also the departments dealing with education, health, war and old-age pensions, labour and unemployment. The Estimates for the year 1922/3 were to be reduced from £603,000,000 to £490,000,000, but then the government decided that a further £62,000,000 should be saved, which brought about the formation of the Geddes Committee. Sir Eric Geddes was Minister for Transport, and a close friend of the Prime Minister, and he was joined on the committee, to investigate national expenditure, by Sir Guy Granet, Lord Faringdon and Sir Joseph Maclay. Predictably Sir Henry Wilson pressed for the abolition of the RAF to effect some of the required savings. The least the other two services would settle for was the return of the Fleet Air Arm and Army Cooperation units to the Navy and Army respectively. Perhaps Trenchard’s attempts to ‘educate’ the chairman bore fruit, because the committee felt that the RAF came out well following its investigations. The members were persuaded that a division of the RAF in this way would lead to duplication, which in turn would lead to extravagance, and this was to echo the 1917 Smuts Report. The committee, in submitting its report to the Chancellor of the Exchequer in December 1921, also remained unconvinced that the RAF was less well administered than the other two services. There was, nevertheless, a recommendation that the RAF’s budget be cut from £18.5 million to £13 million, including the cost of the RAF in the Middle East. Excluding the costs of the latter, the Cabinet approved the sum of £10.75 million.

The exclusion from the Estimates of the costs of maintaining RAF squadrons in the Middle East could be justified on the grounds of operational necessity in the three theatres of operations, Palestine, Iraq and Egypt. Thus, in contradiction to the Geddes recommendation that the RAF strength of five squadrons in Egypt and Palestine could be reduced, to effect a saving of £2.5 million, Winston Churchill had raised the strength to eight squadrons. In a statement to Parliament on 9 March 1922 he stressed the success achieved in substituting air for ground forces. These eight squadrons represented one-third of the entire squadron strength of the RAF, and were concentrated around Baghdad to provide ‘the principal agency by which the local Levy forces all over the country are supported’.

Trenchard still had his RAF, but at a price, and it seemed that he had a stark choice. He could cut back on the front-line strength, already reduced to a mere twenty-nine squadrons, or cut back on spending on training establishments, without which he could not create the foundations of a well-trained and efficient air force. In the event Trenchard decided to reintroduce the wartime scheme of training NCOs to become pilots. Additionally the rehousing of officers and men at home stations was postponed, and the staffs of overseas commands were reduced. Chapter 5 explains how the lack of funds prevented Trenchard from modernizing the RAF’s aircraft inventory but how he helped keep the struggling aircraft industry alive by issuing orders for a succession of prototypes. This at least permitted the various firms to keep a basic design and construction staff in employment.

1922 – 1924

Reassessment of the Air Threat to the UK

In April 1922 the Standing Defence Sub-Committee of the CID, with Balfour in the Chair, rendered a report on the dangers to which the UK was exposed in the event of air attack. The two salient points were firstly, that the continental air threat demanded a greater degree of preparedness than then existed, and secondly, if somewhat bizarrely, that France constituted an air menace. The Chiefs of Staff did not attach much importance to any threat from France, but the politicians took a contrary view. The French had the largest air force in Europe, with 596 combat aircraft, and in the politicians’ view this might lead them to be prepared to take risks in diplomacy. Consequently Britain needed a force that could both defend the British Isles and retaliate against France. The matter had further received consideration by the Standing Defence Sub-Committee, and Balfour and Trenchard had submitted notes with a view to obtaining a policy decision either from a full meeting of the CID or the Cabinet.

On 29 May 1922 Balfour went further in a note to Trenchard. He considered Britain’s position to be one of extreme peril. Expansion of the RAF was necessary, but Trenchard, in reply, opined that to attain and maintain air parity with France would require conscription. The last thing Trenchard wanted was a too sudden expansion before his Cranwell and Halton schemes had had a chance to bed in and provide the permanent cadre of officers and men upon which to build up an enlarged air force; i.e. he had not then built ‘the foundations of a cottage on which to build a castle’. Instead the Air Staff proposed a small mixed force of regular and auxiliary squadrons that could be expanded on the outbreak of a war. Once the nucleus was established a larger nucleus could be planned, taking the force to fifty squadrons on the outbreak of war. But since the French had the capacity to increase their strength to more than 1,000 aircraft, the RAF would still be numerically inferior, and superior enterprise and efficiency would be necessary to restore some balance. Trenchard and the Air Staff felt that a force of twenty-three squadrons would be a powerful deterrent to French aggression, and on 3 August 1922 the Cabinet approved. The government was in fact approving a force of five hundred machines at an increased cost of £2 million per annum, £900,000 of which would be found by making economies in the following year’s Air Estimates.

Change of Government – Sir Samuel Hoare becomes Air Minister

At this time Lloyd George was still Prime Minister, but in October 1922 the Coalition fell. Out went Austen Chamberlain, Worthington-Evans and Freddie Guest. And the inquiry that was set up to look into the system of air and naval cooperation, and intended to reconcile the differences between the two services, was never completed. With Bonar Law back as Prime Minister, the post of Air Minister was offered to Lord Londonderry, who refused, since he was heavily committed in Northern Ireland as Education Minister, and so Sir Samuel Hoare was offered it, although he had not previously held public office. Hoare was a back-bencher who had played a significant part in bringing down the Coalition government and he was advised by Bonar Law that, in accepting the post, he might only hold it for a few weeks, for the Prime Minister had it in mind to divide the RAF between the Army and the Navy, in which case the post would no longer exist. The advice that the RAF and Air Ministry were too expensive a luxury came from Sykes, Bonar Law’s son-in-law. Not only was the future of the RAF in jeopardy, but Bonar Law believed that Britain should move out of Iraq, where Sir John Salmond had recently taken over command. Finally Hoare was advised that the post would not be in the Cabinet.

It is difficult to imagine anyone accepting such a position on these terms, but Hoare was ambitious. He was a member of an old banking family, was a second baronet, 42 years of age, fluent in Russian and had other intellectual interests, but knew little about air matters. Perhaps for a man who expected to be Air Minister for only a few weeks this did not matter: after all, his only flying experience had been to fly in an airship over Rome during a British military mission to Italy. In spite of the Prime Minister’s declared intention to disband the RAF, Hoare was determined to lose no time in learning everything he could about military and civil air matters, and except for ten months in 1924 when there was a Labour government in power, he was destined to be Secretary of State of Air until the end of the decade.

On meeting Trenchard, Hoare made no mention of Bonar Law’s intentions regarding the future of the RAF, and it took some time for mutual trust and confidence to be built up between the two men. Trenchard, for his part, appreciated Hoare’s affability and intelligence, but felt that he needed to be ‘educated’ in air force matters. He expressed his sentiments in a letter to Salmond in India, telling him that Hoare wanted to know about the dispute between the Army and the Navy and was keen to get into the Cabinet, where he could better put the RAF’s case. The more Hoare got to know about Trenchard, the more he understood the latter’s single-mindedness and determination to develop an ‘air force spirit’, an air force with its own strategy and tactics. He saw Trenchard as a prophet and his role as political interpreter.

Sir Samuel Hoare Bt MP.

Hoare v. Earl of Derby and L.S. Amery

Hoare was appointed Secretary of State for Air on 2 November 1922. His Principal Private Secretary was Christopher Bullock, an exceptionally able civil servant who had served as Churchill’s Private Secretary and was an ex-RFC man. Following the formation of the new government, Hoare found himself opposite the Earl of Derby at the War Office and L.S. Amery at the Admiralty. Since he did not like the office he had been given in Adastral House, home of the Air Ministry, he moved to Gwydyr House in Whitehall, close to the other two service chiefs, both of whom were ready to carry on the fight to regain their air components and close down the RAF. Derby’s plan was for the liquidation of the RAF, and as a sop to Hoare, to offer the latter a post of Vice-President of the Army Council, with special responsibility for Army aviation. Amery wanted Hoare to surrender all military aviation, leaving his department the responsibility only for civil air matters, so that the creation of Empire air routes could receive its undivided attention. Behind the scenes Beatty was busy lobbying Parliament, and at a Lord Mayor’s Banquet in the London Guildhall he gave a thirty-five-minute speech during which he made an unconcealed attack on the RAF. By then Hoare was clear where he stood, and was prepared to fight to save his department.

Admiral, the Earl Beatty.

In February 1923 Hoare brought matters to a head and put the argument for an independent air force to the Prime Minister. He made it clear that the strategic employment of airpower was only possible with a centralized force, although he saw no reason why such a force could not have military and naval wings. The alternative was two separate air forces, which would not be capable of operating strategically, that is outside the theatre of land or sea operations, since both forces would be trained and equipped to work closely with their respective arms. Hoare prevailed upon the Prime Minister to delay a decision one way or the other on the grounds that any sudden change in the status of the RAF on the scale envisaged could cripple it. What followed is dealt with in Chapters 2 and 6.

Hoare and Sefton Brancker

Sir Sefton Brancker had succeeded Sykes in the retitled post of Director of Civil Aviation, but unlike Sykes he did not have a seat on the Air Council, yet both he and his small department was answerable to the Council and not to the Secretary of State. But to sit in Air Council meetings, where military air matters would have predominated, would have meant that civil aviation would have been overshadowed, and Sefton Brancker was not prepared for the inevitable disagreements, particularly when it came to spending priorities. He was prepared to get on with the job on his own, working to the best of his ability. He was a good organizer and soon established a national air service. He was short in stature, dapper, monocled, charming and high spirited. He displayed energy and shrewdness in his pursuit of a mission to increase the number of flights and route miles flown. For his part, Hoare admired the work of QANTAS in Australia, which united the scattered communities of that continent in the way he hoped that Brancker’s efforts would unite the scattered outposts of Empire. To permit the airlines to develop to take on the task of providing long-range air travel, the Hambling Committee made its recommendations (see Chapter 2), and this led to the formation of Imperial Airways, a single monopoly company formed from six constituent airlines.

Presentation of the Air Estimates for 1923/24

On 14 March 1923 Hoare presented the Air Estimates for the financial year 1923/4. In his speech he compared the output of 300 civil and military machines in Britain during 1922 with the 3,300 machines built in France during the same period, of which 300 alone were civil machines. Some sources put the figure for Britain as low as 200 machines overall, but this only emphasizes the inequality in numbers. From a total of £11,880,000 in the Estimates, only £287,000 was earmarked for civil aviation. An alternative means of funding civil aviation was to grant subsidies, but this could only be at the expense of military flying. In this sense Trenchard and Brancker were competitors for limited funds, and the demands of both men were ultimately Hoare’s responsibility. Hoare compared the Naval Estimates of £58 million and the Army Estimates of £52 million with the £12 million granted to the RAF. If a ‘one-power’ standard was to be applied to the Air there would either have to be reductions in the Navy and Army Estimates to release the necessary funds for an increase in air strength, or an immediate increase of £5 million, rising eventually to £17 million, if Britain was to keep pace with the other Great Powers. He impressed upon the House that, with little more than double the present cost, the RAF could experience a fourfold increase in numbers. In the meantime the RAF had quality, if not quantity. Fifteen squadrons were being formed for home defence, to be in place by April 1925, with three squadrons for the Navy, and there would be a new Auxiliary Air Force and a Reserve.

Sir Sefton-Brancker,

Director of Civil

Aviation.

In the ensuing debate Lord Hugh Cecil, the MP for Oxford University, found it difficult to understand a policy that made preparation for defence that was sufficiently large to be costly but not sufficiently large to be efficient, a view shared by RAF officers. Captain Wedgwood Benn wanted an assurance that the Navy now regarded the RAF as an independent service, and he reminded the House that, during the First World War, the Admirals displayed little interest in the Air yet desired their own Naval Air Arm. Sykes, by then an MP, warned that if the Navy and the Army obtained separate tactical units there might be pressure to dispense with the development of long-range bombing when this should be the subject of particular attention, a point made by Hoare to the Prime Minister.

Bonar Law’s Resignation – Baldwin becomes Prime Minister

Bonar Law’s illness was catching up with him, and in May 1923 he had to step down. His place as Prime Minister was taken by the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Mr Stanley Baldwin. Hoare was asked to stay on as the Secretary of State for Air, and Baldwin offered him a seat in the Cabinet. He appreciated the offer, not only for what he could do for the RAF, but for giving civil aviation a voice, through him, in Cabinet. Notwithstanding the advantages, Hoare still faced public ignorance on Air matters, so he decided to take to the air on official journeys to help publicize flying. The Morning Post condemned Hoare for wasting money by not using conventional, less costly, means of transport, describing his flights as ‘dangerous and objectionable stunts’. Hoare naturally took the opposite view, and wanted to make flying an everyday unsensational occurrence. In August he flew to the International Aeronautical Exhibition at Gothenburg with his wife and Sefton Brancker in a DH34 airliner of Daimler Airways. He worked hard to establish Imperial Airways, but with so little money available for civil aviation research, long-distance aircraft were not available to cover the vast distances in reaching Egypt, India, Australia and New Zealand economically and in reasonable time, which is why airships were such an attractive alternative to fixed-wing aircraft. Later, at an Imperial Economic Conference in London, Hoare outlined the financial difficulties in establishing Imperial air routes, and announced that money had been put to one side for the construction of an experimental aircraft capable of long-distance flights. This was followed by a demonstration at Hendon of between fifty and sixty military and civil aircraft to emphasize how aeronautically determined was the Air Ministry.

Stanley Baldwin.

The First Labour Government

Parliament reassembled in the autumn of 1923 against a background of rising unemployment. Baldwin had still retained most of Bonar Law’s ministerial team, and felt bound by the latter’s pre-election promises not to impose tariffs nor to extend Imperial preference by duties on food. Restricting the flow of imports would give the home market to domestic firms and thus stimulate employment. Baldwin was therefore keen to call an election to bolster his own position and to permit him to form his own ministerial team. So he confided in Hoare, the Cabinet newcomer, that he planned to ask the King for a dissolution of Parliament. Hoare was not keen. Having at last got a Cabinet post and having worked out his long-term programme for his department, he did not want to risk losing office, which is precisely what happened. In the General Election the Conservatives lost ninety seats in the House of Commons, and in came Ramsay MacDonald at the head of the first-ever Labour government, with the Liberals in coalition. This might have been the moment for Trenchard to go with Hoare, but in a letter to a colleague he wrote, ‘The more I stay on as CAS the more difficult it is to go. Now I try to make the excuse that the change of government precludes my going. After the Labour government comes in (if it does come in) I think we shall have more friends than ever before.’ Friends or not, Trenchard would have to ‘educate’ yet another Air Minister, for the new incumbent lacked departmental knowledge like his predecessors. Brigadier-General C.B. Thomson had been appointed as Secretary of State for Air, but he had failed three times to secure a seat in the House of Commons after joining the Labour party in 1919. The Prime Minster had therefore to elevate Thomson to the peerage in order to secure his services as Air Minister, and William Leach MP was appointed as Under-Secretary of State to speak for the Air Ministry in the House of Commons.

Ramsay MacDonald, Britain’s first Labour Prime Minister.

Reaction to the new government was awaited with interest. To begin with, the new Labour MPs were largely free from the prejudice in favour of the Army and Navy. Trenchard was astute in working with men in government whose social background was very different from those with whom he had dealings in the past. He had paid the trade union leaders the compliment of seeking their advice before instituting the Halton apprentice scheme, and now he faced a former clerk as Prime Minster, an engine driver in the Colonial Office, a foundry labourer in the Home Office and a millhand as Lord Privy Seal. Thomson would have to face Lord Chelmsford at the Admiralty and Mr Stephen Walsh at the War Office. It being a coalition government, MacDonald offered government posts to his Liberal partners. Lord Haldane, who was appointed Lord Chancellor, was the man who had remodelled the British Army and now found himself chairman of the CID, in which he had previously served and which had given him experience of inter-service rivalries. Given the pacifist tendencies of a number of Labour MPs, including the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Mr Philip Snowden, the three Service ministers and their Service chiefs might have feared the worst, but it was Haldane who prevailed upon the Chancellor to pass the Service Estimates from the point of view of the Treasury.

Lord Thomson with his Principal Private Secretary,

Christopher Bullock.

Debate on the Air Estimates for 1924

No sooner had the government taken office than Hoare was prodding the Under-Secretary of State into a declaration of policy. In the Commons on 19 February 1924, Hoare moved: ‘That this House, whilst earnestly desiring further limitation of armaments so far as is consistent with the safety and integrity of the Empire, affirms the principle laid down by the late Government and accepted by the Imperial Conference, that Great Britain must maintain a Home Defence Air Force of sufficient strength to give adequate protection against air attack by the strongest air force within striking distance of her shores.’ He informed the House that in October 1922, the time of the Chanak crisis, there were only twenty first-line aircraft available for home defence, but thanks to a Conservative government there were about eight fighters and twenty Army Cooperation aircraft. He then cited a member of the French Chamber of Deputies and First World War pilot, M. René Fonck, who had calculated that a force of 500 aircraft could, in the space of a single night, obliterate a city the size of Paris. By comparison France had 1,000 front-line aircraft, 600 of which belonged to the French Independent Striking Force and 400 were Army Cooperation aircraft. The Expansion Plan described in Chapter 2 would take Britain’s Home Defence Force to 600 aircraft. Hoare finished by assuring the House that he did not wish this force to herald an arms race, nor was hostility towards Britain’s neighbours implied. Clearly Hoare and Trenchard were prone to overstate the case for offensive defence. The RAF would have needed a fleet of four-engined heavy bombers to create havoc on the scale envisaged.

Mr Leach replied for the government to the effect that he was not alarmed by the disparity between the British and French force levels, but he affirmed that there would not be any change in policy. With regard to aircraft to equip the expanded force, there was a sufficient number to equip squadrons formed during 1924. Until sufficient aircraft were available, some squadrons would have to make do with training aircraft. He said that the further development of airships was being considered and would be encouraged, and that civil aviation would be similarly fostered. With regard to the disparity between Britain and France, Mr Leach’s opinion was that even if Britain was circled with defensive fighters giving a ratio of 50:1 in Britain’s favour, there would still be those who would say that that was not enough. The only impregnable defence that he could see was a changed international atmosphere, and he added, ‘If we continue to put fear at the helm and folly at the prow we should steer straight for the next war.’ But at least Trenchard could content himself that the Expansion Plan would pass the Commons, and in the Lords it was left to Lord Londonderry to confront Lord Thomson, who was to make his first statement on Air policy. He confirmed what Leach had said: Britain would confer with other nations to try to find a method of all-round disarmament. His speech created a favourable impression in which he expressed the view that, for the Labour government, ‘the flower of idealism is rooted in common sense’.

The Air Estimates were published on 7 March. Trenchard got the £2,840,000 he needed to equip eight new Home Defence squadrons, while the Navy was to experience a £2 million cut and the Army one of £7 million; but even then there was a huge disparity between the RAF and the other two services. The Estimates, which had been prepared by the former Conservative government, were introduced by Lord Thomson, and contained two fresh votes for educational and medical services. The largest individual increase was for technical equipment and research. There would be some reconditioning of existing aircraft and engines, but the new squadrons, including those to be employed on naval cooperation, would receive new aircraft, which meant no relaxation in experiment and research. The Estimates did not provide for airship development, but this was being actively considered, and a decision would be communicated to Parliament in due course, any extra spending being the subject of a Supplementary Estimate. On 25 May Mr Leach had more to say on airships. He regarded the preceding few years of aerial endeavour as moribund and the development of airships as disappointing. He said:

After the war, when the general slump began, plant, airships and material were offered free to anybody who would have gone on with the scheme of airship development. Not an offer was forthcoming. Efforts were also made to enlist the interest of the Dominions, but these came to nought. So for three or four years nothing has been done except that the Research Department has been accumulating knowledge. However, throughout these years Commander Burney, the Member for Uxbridge, has displayed considerable faith in lighter-than-air travel and kept alive the flame that would otherwise have been extinguished.

This ignored the work done by Vickers, and it did not stop the government rejecting the Burney Airship Scheme for six airships to be built over a number of years by private enterprise. The government took the view that military considerations should be kept in view at all times. Accordingly the State would build one at Cardington, which could be used for commercial flights, but in time of war could be used for naval reconnaissance. This was to be the R101, and in parallel private enterprise would build R100 with State help. In addition the State would recondition two existing airships, the R33 and R36. This gave Hoare the opportunity to denounce the government, and he retorted:

Today the Hon. Gentleman has come before us, not only as a full blooded Imperialist, but as a full blooded militarist as well. The scheme of our late Government was a commercial scheme. The sole original contribution of the present Government to the development of British aviation is the building by direct labour of a military airship that the late militarist Conservative Government would never have dreamed of proposing. The Under-Secretary has made a travesty of the late Government’s scheme, for we proposed a loan, without interest, of £400,000 a year, repayable from profits, and at the end we expected six large airships operating a commercial service between England and India. The present Government’s scheme is likely to be much more expensive, for it has no ultimate object in view, and at the end of three years would be little further forward. There are few Air Ministry officials who know anything about airships, so a great airship department must be created, and a big government organization set up for a single airship – and, what appears no less dangerous, a new construction organization at Cardington. What does the Government intend once the experimental period is over?

Mr Leach replied:

As to where we are going, what the nature of our policy, what is visualised years ahead – I could not tell yet. The Government is looking at a more or less dead industry which we want to put on its feet if possible. The airship industry has a chequered past; there is no certainty about its future security. The six airships of the Burney Scheme would have taken seven years to provide, whereas the three under the Government scheme – one new and two reconditioned – should be provided inside three years.

It is a sad irony that by the time the R101 was ready for its maiden flight to India, Lord Thomson would again be the Secretary of State for Air and would die, along with Sefton Brancker, when the R101 crashed in flames near Beauvais in France in October 1930.

The Auxiliary Air Force Knowing of Haldane’s Army reforms, which included the institution of the Territorial Army, Trenchard would flatter Haldane by proposing a similar RAF force of ‘weekenders’. Not only would this bring Haldane ‘on side’, but it would also appeal to the cost-conscious Snowden. The idea of ‘winged Terriers’ was thus approved by the Cabinet. (Terriers was the name given to members of the Territorial Army.) To be fair, Trenchard had already spoken of the need for a Reserve in Paragraph 4 of his 1919 Memorandum, so this was not a new idea. He had tried it on Churchill when he was the Minister for War and the Air, but Winston did not support the idea of training part-timers as pilots.

The Fall of the Labour – Liberal Coalition

The Labour – Liberal coalition government was not in power long enough to have any appreciable impact on air policy, and it did little more than confirm the previous Conservative government’s Expansion Plan and put the airship-building plan into operation. They were concerned with discussions over the defence of Singapore, and during their period of office the Fleet Air Arm was formed, albeit with RAF crews. With regard to the policy of air control, pacifist elements in the Labour Party would ask why the RAF was bombing women and children. Trenchard wrote to Air Vice-Marshal Higgins in July 1924 that he believed that, although there were repeated calls to halt air-control operations, the Ministers understood. Lord Thomson wrote the following words in a Command Paper of air-control operations in Iraq: ‘Air action can be taken swiftly at the focus of trouble and before disturbances against which it is directed have time to permeate to a larger area. It has the immense advantage that, compared with the slow movements of ground forces over unfamiliar country, it offers to the tribesmen no chance of loot or retaliation by ambush or concentration against small ground forces.’

Ramsay MacDonald, it must be remembered, headed a coalition government that included Liberals. He had therefore to keep them ‘on board’ if his government was to survive. Only seven years had elapsed since the Bolshevik revolution in Russia, and in 1920 the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) was formed. When one remembers that the Spartacists (Communists) had staged an uprising in Berlin in 1919 there was always the risk that the CPGB would attempt to follow suit and provoke a workers’ uprising to overthrow Britain’s democratically elected government. Lenin had tried to alleviate the economic plight of his people with his New Economic Plan, but the situation had been aggravated by years of civil war between the Bolsheviks and the White Russians, when the RAF had assisted the White Russian forces. Given these circumstances and Ramsay MacDonald’s sympathy for Russia, with his proposed ‘Bolshevist loan’, as The Times called it, there was growing concern that the government might be playing into the hands of the Communists and their sympathizers. For example, the government had withdrawn a prosecution against Mr J.R. Campbell, acting editor of the Workers’ Weekly. Mr Campbell had been arrested under the Incitement to Mutiny Act of 1797 for an article urging soldiers not to fire on fellow workers. The Conservatives tabled a Motion of Censure and the Liberals demanded a Select Committee of Inquiry. The matter was debated on 8 October 1924, when the Attorney-General, Sir Patrick Hastings, said that the decision not to prosecute Mr Campbell was his, but that the Prime Minister and Home Secretary had been consulted. With hindsight the Prime Minister might have been rash in making the winning of the votes on both the Resolution and the Amendment a condition for Labour remaining in office. The vote was 364 to 198 against the government, and so the Prime Minister went to the King to ask for a dissolution of Parliament, paving the way for a General Election on 29 October.

Suspicion was further aroused that the Labour party was playing into the hands of the CPGB with the publication of the famous ‘Zinoviev’ letter by The Times four days before the election. The authenticity of this letter is in doubt, but the effect of its publication, authentic or not, was to lose Labour the election. Mr Zinoviev was President of the Communist International in Moscow, and the mission of this body was to spread the Marxist/Leninist creed in the hope of bringing about Soviet-style governments around the world. This letter was addressed to the Central Committee of the CPGB, urging the proletariat to rise up in insurrection. A protest from the Foreign Office to the Russian Chargé d’Affaires in London only added substance to the argument that the letter was authentic. That the CPGB would have been unsuccessful in any attempt to get the British workers to overthrow the government by force there can be little doubt. The very reason for the formation of the Labour party in 1900 was the determination of the trade unions to gain power through the ballot box, and in this they had succeeded in twenty-three short years. Had Ramsay MacDonald been faced with even a limited attempt at insurrection he might have had to order troops to fire on rioters. But 1924 was also the year of Lenin’s death, and Stalin, who assumed power in the Soviet Union after a brief power struggle, was determined to consolidate Socialism in the USSR before exporting it to the rest of the world. In this he fell out with Trotsky, who was eventually forced to leave Russia and obtain exile in Mexico, until Stalin’s ‘hatchet’ men went after him and ended his life. Be that as it may, it ended the term of the first Labour-led government. Labour lost forty seats and the Conservatives were returned with 419 seats, gaining 161. The Liberals dropped to third place, where they have remained ever since, losing 116 seats, which left them with only forty Members of Parliament. From now on Labour would be His Majesty’s main Opposition.

1925-1926

The New Conservative Government

It was not until May 1929 that Labour returned to power, again in coalition with the Liberals. Until then there would be a Conservative government, which for Trenchard would mean stability for the remainder of the decade and up to his retirement. He would have Mr Baldwin as Prime Minster, with Sir Samuel Hoare as Secretary of State and Sir Philip Sassoon as Under-Secretary. Baldwin formed his government on 7 November 1924, and reappointed most of his previous Cabinet. Austen Chamberlain became Foreign Secretary, Neville Chamberlain the Minister of Health; Joynson-Hicks the Home Secretary and Winston Churchill the Chancellor of the Exchequer. Hoare lost no time in getting back to work on air business. Having firmly expressed his view on airships when in opposition, he had to make clear what the new government’s policy would be. On 18 November he went to Cardington with Sassoon and Air Vice-Marshal Sir Geoffrey Salmond. Group Captain Peregrine Fellowes, Major Colmore, Colonel Richmond and Major Scott made up the party. Airships had captured the interest of Parliament, and by making his visit to Cardington he was wearing his ‘civilian’ hat. In spite of the intense use made of airships in the First World War, Trenchard had virtually written them out of his 1919 Memorandum, but then he was ‘strapped for cash’, and a small research team at Howden was all that was provided for. This indicated an open mind on the matter, but the military use of airships was limited, given their slow speed and lack of manoeuvrability. The Labour government, on the other hand, had committed public funds to the building of the R101 and the refurbishment of airships R33 and R36. The R33 was being equipped as a test vehicle so that air pressures and stresses could be measured during violent manoeuvres. The R36 was having its nose strengthened prior to an experimental trip to India to test the feasibility of regular air services. With his military hat, Hoare explained government policy at the Lord Mayor’s Banquet. He reported that eighteen of the fifty-two planned Home Defence squadrons would be formed by the end of the financial year, and he praised Lord Thomson for his continuity of policy. He then went on to state the defence benefit of reduced journey times by airship, since better air communications would help solve, economically, many urgent questions in the Near East. Sefton Brancker was meanwhile promoting the idea of Empire air communications by taking a stage-by-stage flight in the second prototype DH50, with Alan Cobham as pilot, to attend a conference with the Indian government in January concerning the big airship scheme.

Air Estimates 1925/6

The Estimates for 1925/6 were introduced by Hoare on 12 March 1925. There would be an increase in the Gross Estimate of £1½ million over Labour’s Estimates of the previous year, taking the total to £21,319,200. The increase would provide for seven new squadrons for home defence. There were fifty-four squadrons already in existence, forty-three squadrons and two flights organized as such, eight squadrons in Iraq, six squadrons in India, four squadrons and one flight in Palestine and Egypt and eighteen Home Defence squadrons. Then there were twenty-one flights for the FAA, and for the first time the Navy made a grant to the RAF of £400,000 in respect of equipment for the FAA. During 1925/6 the number of squadrons to be formed would be two Regular, one Special Reserve and four Auxiliary Air Force. From First World War days Farnborough had produced service aircraft, but the importance of experiment and research was underlined by reserving Farnborough for this purpose. Finally Hoare said that the total provision for airships would be £500,000, and an initial payment had been made to the Burney Airship Guarantee Company.

The Auxiliary Air Force squadrons did prove to be a conspicuous success, in spite of Churchill’s earlier objections, for Winston did not believe that ‘weekend fliers’ would be of much use in war. These squadrons had the advantage of keeping their personnel, whereas the regular squadrons experienced a constant turnover. John James makes this point quite clear in his book The Paladins, saying that the RAF had the choice to keep their pilots with squadrons and perhaps wings, like officers of Army regiments who served their careers with their regiments, but chose instead to post aircrews to squadrons for a tour of duty, sometimes never to return to that squadron. All ranks of auxiliary squadrons therefore got to know each other very well. In the same year university air squadrons were formed to introduce undergraduates to flying and the RAF, in the hope of recruiting brains into the service.

Problems with the Expansion Plan

By the summer of 1925 progress on the Expansion Plan saw twenty-five of the planned fifty-two Home Defence squadrons formed, but with the impending conclusion of the Treaty of Locarno (see the opening paragraph of Chapter 3), the Cabinet began to wonder whether the rate of progress should not be slowed down. The favourable international situation, together with the need to be seen to be honouring the spirit of international disarmament, could not be ignored. The French Army had been withdrawn from the Rhineland, Germany had been admitted to the League of Nations and the projected expansion of the French Air Force had not materialized. Economy in defence expenditure seemed a reasonable aim in this atmosphere, and Churchill wrote privately to Trenchard on 11 October 1925:

I have not at all altered my views as to the desirability of a separate Air Force so far as efficiency and leadership in the air are concerned. The expense is another matter, and I am not convinced that large savings would not result from the less satisfactory solution of division. Everything now turns on finance, and I am sure that if the Air Force is going to continue to swell our expenditure upon armaments from year to year it will draw upon itself a volume of criticism which will bring the question of division into the forefront of defence problems.

The Navy reproach me bitterly for only criticising and attacking their expenditure while the Air Force they say is favoured and the Army let alone. You have only to read the papers to see how cruel is the pressure to which I am subjected. We are at present heading for large increases in expenditure next year with consequent reimposition of taxation. I am sure the Cabinet will recoil from this prospect when they are confronted with it and that desperate efforts will be made to cut down.

I do hope that you will be able to help the Treasury in this task. You have many friends there who have confidence in your own frugality of administering and see the usefulness of your intervention against the extravagance both of the Navy and of the Army. I am sure that the present relations not only justify but demand a complete reconsideration of the rate of the expansion scheme, and I should be bound to resist by every means in my power any attempt to carry the total of Air Votes in the coming year beyond the figure under all heads for this.

W.S. Churchill

This was certainly a ‘shot across the bows’, with yet another threat that the RAF would be divided up between the Army and the Navy, and this time from one of Trenchard’s supporters and one-time Minister for the Air. But in 1925 Winston was the Chancellor of the Exchequer, charged with the task of keeping public expenditure under control. When a Cabinet committee was set up under Lord Birkenhead to consider the Expansion Plan for home defence, Trenchard wrote to Ellington, then AOC India, in a letter dated 25 November 1925, expressing the opinion that the committee realized the importance of having a proper scheme of defence and that substantial savings could not be effected by stopping or delaying the plan, but on 27 November the committee recommended that the rate of expansion be slowed down:

The present world position would not justify us in cutting down our forces below the limits of safety. In addition to political security, some measure of practical security is required. We are therefore of the opinion that the scheme of Air Force expansion announced in 1923 should remain the goal at which we aim and we do not believe that the Cabinet in remitting this question for our consideration had any other thought in their minds.

The recommendation to the Cabinet was that the completion of the Expansion Plan should be delayed until 1935/6. On 3 December the Cabinet agreed. This was two days after the signing of the Locarno Treaty in the Foreign Office, and the decision was announced to the Commons by Hoare on 25 February 1926, when he introduced the Air Estimates for 1926/7. There was a £450,000 drop from the previous year, and he explained to the House the government’s decision to relax the efforts to complete the plan on time in view of the international and financial position. Only two extra regular squadrons were to be provided that year, with a third that had become available from overseas. Finally, he stressed that there was no change in the total strength to be attained, only a slow-down in the rate of expansion.

The Colwyn Committee

The government had therefore considered Britain’s good relations with France and the general improvement of the international situation following the signing of the Locarno Treaty. Britain could not be seen to be rearming when disarmament should assume greater importance in the scheme of things, but the government could present the Expansion Plan as purely defensive. Be that as it may there had been a steady rise in the Service Estimates since 1922, and so the government set up a ‘Special Services Economy Committee’ on 13 August 1925. This was to be a Treasury committee under the chairmanship of Lord Colwyn, a businessman who had served on similar bodies in the past. His committee would have no service representatives on it and he was to be assisted by Lord Chalmers and Lord Bradbury, two ex-Permanent Secretaries to the Treasury.

Since the spotlight was on all three services in an attempt to cut defence expenditure, the Navy seized the opportunity to resurrect the old dispute with the RAF over the FAA. The Navy’s case was that it would be more economical if the Navy ran its own air arm. In spite of the Trenchard – Keyes agreement, which laid down the ground rules for the operation of RAF Coastal Area and RAF involvement in naval operations afloat, and was working well enough, the Admiralty could not resist the opportunity presented by the Colwyn Committee investigations. But with Admiral Beatty off sick at this time, the Admiralty’s case was not presented as well as it might have been. The claim was made that the Trenchard – Keyes agreement was not in fact working well at all, and sure enough the Army then leapt in with its claim for a return of air units working with the Army.

This was well-trodden ground, but Trenchard had, yet again, to trot out the usual defence of his position. It seemed he was back to Square One. Again he repudiated the idea that his agreement with Admiral Keyes was not working. There was an absence of duplication in aircraft procurement, aircrew training and research and development, etc. What he particularly objected to was that whenever the question of economies were raised the Army and the Navy would renew their attacks upon his service. He said that the amount of time which the air service had to devote year after year to defending its existence was incalculable. It was bad for the whole service, it was bad for the development of the country’s defences and it was bad for the economy itself.

The Colwyn Committee reported to the Prime Minister on 23 December 1925, having collected a considerable amount of evidence, both oral and written. The committee found that the figures for the Service Estimates were inconsistent with the ‘Ten-Year Rule’. The total of £127,000,000 could not be justified, given the signing of the Locarno Treaty, the assessment of a lack of threat to the country and the proposals for international disarmament. This was put down to a lack of coordination between the service departments in framing defence policy and controlling expenditure. The CID, it seemed, had not been able to exercise the necessary control, yet the committee did not believe that a combined Service Department or Ministry of Defence was the solution, any more than the abolition of the Air Ministry. Instead, the committee reaffirmed the view that an Air Ministry administering a unified service carrying out all the air work for all three services would achieve the greatest economy, particularly if air substitution was extended. With regard to the FAA, the committee found that substantial additional reductions in both Navy and Air Votes would accrue if the Air Ministry’s control over the FAA was strengthened. It was felt that having naval officers as observers made sense because the man who was observing a situation afloat should be a man who understood naval matters, the speed and course of ships either sailing or closing for action, tides and all other things to do with naval deployments. But when it came to pilots no reason could be found by the committee for the employment of naval officers beyond the 30 per cent of officer personnel normally embarked as pilots on carriers and other warships. The committee did accept that this 30 per cent should be eligible for senior appointments in Air Force units connected with the training and maintenance of the FAA. The remaining 70 per cent should remain RAF officers, including a suitable proportion of officers on short-service commissions, so as to provide an adequate reserve on an economical basis. The committee also found that naval ratings should be substituted for RAF other ranks in the carriers if a definite reduction in numbers would thus be effected.

The Colwyn Committee then recommended reductions in the Service Estimates, £7½ million for the Navy and £2 million each for the Army and RAF. The Navy was criticized on administrative grounds for ‘being completely out of touch with up-to-date civilian experience, particularly in respect of dockyard organization where economies might be effected’. The Army was found to be efficient and prudent, while the Air Ministry was censured for not giving full value for taxpayers’ money. This was, however, put down to the relative lack of experience of staff in the Air Ministry, to frequent changes in government policy and the perpetual inter-departmental warfare. The committee concluded that only radical revision of the existing standards of defence would effect large and lasting economies, but this was not in their remit.

The Navy predictably opposed the committee’s proposals. The Admiralty had lost £7,500,000 and the battle to regain control of the FAA. It was then reported that the Admiralty would accept the financial cuts but would ignore those clauses that related to the 70 – 30 per cent officer manning of the FAA. It thus appeared that the Navy had left itself the option of a fresh attack on the RAF at some time in the future, so Trenchard sent a ‘private and personal’ letter to Churchill. He wanted a ‘once and for all’ assurance that the Colwyn Committee’s findings would be endorsed, inasmuch as the RAF would then be left alone to get on with its job. Churchill was sympathetic, and sent Trenchard’s letter to the Prime Minister, the latter being happy to publicly endorse the relevant passages in the Colwyn Report. He went further in response to a question in the House of Commons in affirming that the government had no intention of reopening the question of a separate air arm and Air Ministry. Imperial defence would henceforth be organized on the existing basis of three co-equal services, and Baldwin urged that controversy on this subject should cease.

Continuing Controversy between the Air Ministry and the Admiralty

But the controversy was set to continue. Heretofore the RAF had raised and trained units of the FAA, but once these units went to sea in carriers and warships they were subject to naval discipline and control. But the RAF shore-based units that were employed on maritime operations, such as coastal reconnaissance and the escorting of convoys proceeding up the English Channel, were under the command and operational control of RAF Coastal Area. The Admiralty was entitled to argue that maritime air operations were the business of the Navy, whether the units involved were shore or ship based. Increased use of naval officers as pilots in the FAA could be justified on the grounds that naval officers better understood naval warfare, but evidence presented to the Colwyn Committee showed that the cost of a 70 per cent manning of the FAA by naval pilots was £400,000 more expensive than an 80 per cent manning by RAF officers. This did not stop the Admiralty laying claim to the complete control of the shore-based aircraft known as Coastal Reconnaissance Flights and airships. Furthermore they wished to have naval officers trained in flying so that they could replace RAF officers in technical posts. At that time there were only two coastal reconnaissance flights in existence, but more were planned, for both home and overseas, and they were manned and administered by the Air Ministry.

A war of words continued, with a brief truce being observed during the 1926 General Strike, when it was ‘all hands to the pump’ to keep essential supplies flowing and to preserve law and order. After the strike had been settled, both the First Lord of the Admiralty and the Air Minister wrote to the Prime Minister, asking for a final and rapid settlement of their claim. On 2 July 1926 Baldwin replied to both men but satisfied neither. He endorsed the principle of an independent Air Ministry, and the arbitration was expressed under four heads:

- The Air Ministry must continue to be responsible for raising, training and maintaining the FAA subject to the adjustments made in the Balfour Report and the Trenchard – Keyes agreement. This provided that there must be a 70 per cent naval and Royal Marine manning of FAA units. Those naval and Royal Marine officers carried dual RAF/naval rank and were eligible for advancement in the RAF.

- Baldwin was not prepared to reverse the recommendations of the Balfour Committee, which provided that at least 30 per cent of RAF officers, whether regular or short service, should serve on aircraft-carriers.

- The 70/30 ratio in favour of the Navy should apply only to FAA units, i.e. not shore-based units employed on maritime duties.

- The question of the coastal reconnaissance flights or naval-cooperation flights, as the Navy called them, should be a matter of cooperation between the two services, as suggested by Austen Chamberlain in his House of Commons statement of 16 March 1922, rather than one of strict subordination. This matter was therefore to be dealt with by the Chiefs of Staff Committee.

The Prime Minister did not deal with the matter of airships. It will be remembered that the R101 was nicknamed the ‘Socialist’ airship, to be built with public money at Cardington, and the R33 and R36 airships were to be refurbished, all in the name of commercial aviation. But there was some justification for the expenditure of public money on the R101 in that it could be used for reconnaissance in a time of national emergency. This would inevitably mean maritime reconnaissance, since airships were no match for aircraft over land, and this, in turn, would mean the Navy laying claim to its manning and operation. The operation of the R101 would therefore only lead to another squabble, which was something the government was keen to avoid.

Baldwin then proceeded to ‘bang heads together’. He felt it was time for the two services to stop the constant bickering, and he told them to enter into a new spirit of cooperation. Both service heads then wrote to each other, giving an assurance of whole-hearted cooperation, and Trenchard backed this up with a letter to all his Air Vice-Marshals, explaining the Prime Minister’s ruling. One tangible result was the agreement that the programme of training and exercises in peacetime should be arranged to secure the maximum amount of cooperation between shore-based units and the Navy. To this end Trenchard worked with the Deputy Chief of Naval Air Staff, Vice-Admiral Sir Frederick Field, representing Beatty, who was still absent from duty owing to sickness.

There was one more hiccup between the two services before the year was out, and that was caused by the inability to attract sufficient naval officer volunteers to fill the 70 per cent quota for the FAA. The Admiralty had proposed training ratings and marines in the same way as the RAF trained airman pilots. The Air Ministry disagreed with this proposal on two grounds. Firstly, the object of providing a core of naval officers with air experience who would eventually be promoted to the higher ranks of the service would be defeated. Secondly, the posts that the Navy could not fill should go to airman pilots, since the latter were experienced at working with aircraft in a flying environment, and they had served a three-year apprenticeship covering various aspects of aircraft maintenance; this was something that naval ratings or marine recruits would lack. The Navy’s response was that it would not reduce its quota, and the First Lord went on to propose the appointment of non-commissioned pilots. The Air Ministry then claimed that this was a new proposal that had not been included in those matters that were the subject of the Prime Minister’s arbitration of July 1926. But Baldwin had other things on his mind and was not going to be deflected by this latest difference between the two services.

1927 – 1928

Presentation of the Air Estimates, 1927/8

On 5 March 1927 the Air Estimates for 1927/8 were published. Parliament was being asked to vote £15,550,000, which was a reduction of £450,000 on the previous year, savings having been made on personnel, works and buildings. There was some compensation in that the spending on technical equipment would increase by £635,000, including new types of aircraft. In Hoare’s words, ‘The policy of replacing aeroplanes and engines of wartime design by modern types is making steady progress and it is the intention that, in future, no more aircraft or engines of wartime designs should be bought.’ A subsidy of £137,000 was to go to Imperial Airways for its European services, and £93,600 for the Cairo – Karachi route. £8,000 was to go to meteorological services, £10,000 for a new wireless telegraphy station and £110,000 for alterations to Croydon Airport, which were scheduled to be completed by 1928.

The Debate on the Estimates took place on 11 March. The Times, in reporting the debate, said, ‘Sir Samuel Hoare has all the scrupulous precision which he proudly ascribed to British aeroplane engines, and, like them on his great Imperial flight last year, he went through the long journey of his Estimates purring like a kitten.’ This did not impress either Conservative or Labour MPs, who felt that too little progress had been made. Among these was Lieutenant-Colonel Moore-Brabazon, who felt that Sir Samuel Hoare’s triumphant speech was cynical, given the rate of progress since the First World War. He recalled how change from one design to another took a matter of months during the war, and referred to the Italians’ ability to prepare their team for the Schneider Trophy races in six months at a time when British technical experts believed that two years would be necessary. Perhaps they had not appreciated that war provides an enormous incentive to make rapid strides, involving expenditure that would never be accepted in peacetime. Indeed, it was the lack of funds in the early 1920s that prevented Trenchard from ordering and the aircraft industry from developing new aircraft types. With 10,000 war-surplus aircraft dumped on the market in 1919, it is hardly surprising that reconditioned DH9As and Bristol Fighters were much more economical, and it cannot be denied that these two gave sterling service in India, Palestine and Iraq during the 1920s.

The debate was characterized by vociferous contributions from those who thought that the RAF vote from a total Service Estimate of £115,000,000 was disproportionately small, and the ‘disarmers’ who thought otherwise. But it was RAF air accidents that excited the greatest interest of Members. The Prime Minister put these accidents down to pilot error, given the adventurous spirit, nerve and temperament of RAF pilots. It was in their nature to take risks, and accidents in training, he felt, were unavoidable. C.G. Grey, the editor of the Aeroplane, took issue with the Prime Minister, and believed that Baldwin had taken considerable trouble to investigate air accidents, yet had based his findings on entirely false premises. Accidents could be prevented, said Grey, if Air Ministry technical experts could be forced to work with greater speed and greater intelligence to equip the Air Force with apparatus that would prevent a large proportion of such accidents.

Bridgeman v. Hoare

On 19 February 1927 William Bridgeman, the First Lord of the Admiralty, wrote to Hoare saying that he had noted the Air Minister’s views on the inability of the Admiralty to man its 70 per cent quota of naval officer pilots in the FAA, and insisted on the Navy’s right to determine for itself who should and who should not fill the pilot vacancies. Again the two Ministers took their dispute to the Prime Minister for arbitration, but Baldwin was preoccupied with his visit to Canada with the Prince of Wales, and no decision was taken in 1927. In January 1928 he was still preoccupied, this time with government business of the new session of Parliament, and so he asked the Lord Privy Seal, Lord Salisbury, to arbitrate on his behalf. But it seems that the Admiralty had grown impatient, and on 10 February issued a Fleet Order altering the period of attachment for naval pilots to the FAA, notwithstanding the Air Ministry’s disagreement and the fact that the whole matter was sub judice. There followed an angry exchange of letters, with Hoare ceasing to address his opposite number in official correspondence with his usual ‘My Dear Willie’, and substituting the formal ‘Dear First Lord’. Bridgeman responded in similar fashion.

On 15 March Salisbury sent his recommendations to the CID. To begin with, it was conceded that the FAA was an integral part of the fleet. This was not the difficult part of the arbitration, since even the Air Ministry could hardly claim to know best how to deploy aircraft from a carrier during fleet operations perhaps thousands of miles from British shores. Salisbury held the view that the FAA hardly differed from any other arm of the service, such as the submarine service and the Royal Marines. Gradually the Air Ministry would have to concede that it was no longer constitutionally nor permanently part of the RAF. Indeed, Trenchard had anticipated as much in his 1919 Memorandum (see Appendix C, page 421, para. 1). But 1928 was not the year to make the break. Naval aviation needed time to develop before it could stand on its own. In the light of the Ten-Year Rule there was no urgency to make a precipitate move.

With regard to the specific matters for which the two services required arbitration, Salisbury’s recommendations were as follows:

- The source from which naval pilots were to be recruited was the ranks of naval officers.